Nowness - Illinois Institute of Technology

Nowness - Illinois Institute of Technology

Nowness - Illinois Institute of Technology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

108<br />

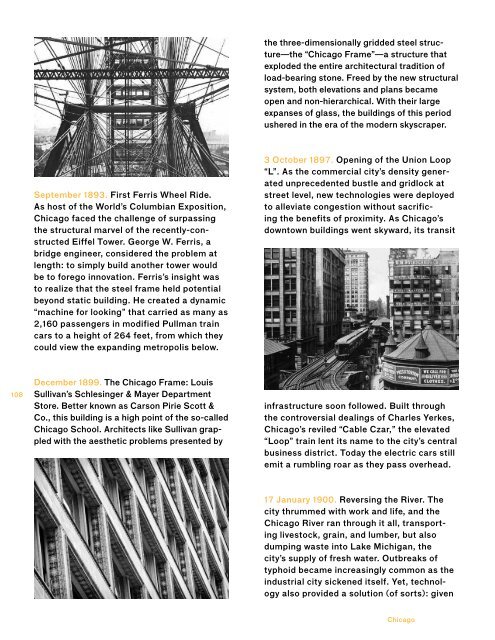

September 1893. First Ferris Wheel Ride.<br />

As host <strong>of</strong> the World’s Columbian Exposition,<br />

Chicago faced the challenge <strong>of</strong> surpassing<br />

the structural marvel <strong>of</strong> the recently-constructed<br />

Eiffel Tower. George W. Ferris, a<br />

bridge engineer, considered the problem at<br />

length: to simply build another tower would<br />

be to forego innovation. Ferris’s insight was<br />

to realize that the steel frame held potential<br />

beyond static building. He created a dynamic<br />

“machine for looking” that carried as many as<br />

2,160 passengers in modified Pullman train<br />

cars to a height <strong>of</strong> 264 feet, from which they<br />

could view the expanding metropolis below.<br />

December 1899. The Chicago Frame: Louis<br />

Sullivan’s Schlesinger & Mayer Department<br />

Store. Better known as Carson Pirie Scott &<br />

Co., this building is a high point <strong>of</strong> the so-called<br />

Chicago School. Architects like Sullivan grappled<br />

with the aesthetic problems presented by<br />

the three-dimensionally gridded steel structure—the<br />

“Chicago Frame”—a structure that<br />

exploded the entire architectural tradition <strong>of</strong><br />

load-bearing stone. Freed by the new structural<br />

system, both elevations and plans became<br />

open and non-hierarchical. With their large<br />

expanses <strong>of</strong> glass, the buildings <strong>of</strong> this period<br />

ushered in the era <strong>of</strong> the modern skyscraper.<br />

3 October 1897. Opening <strong>of</strong> the Union Loop<br />

“L”. As the commercial city’s density generated<br />

unprecedented bustle and gridlock at<br />

street level, new technologies were deployed<br />

to alleviate congestion without sacrificing<br />

the benefits <strong>of</strong> proximity. As Chicago’s<br />

downtown buildings went skyward, its transit<br />

infrastructure soon followed. Built through<br />

the controversial dealings <strong>of</strong> Charles Yerkes,<br />

Chicago’s reviled “Cable Czar,” the elevated<br />

“Loop” train lent its name to the city’s central<br />

business district. Today the electric cars still<br />

emit a rumbling roar as they pass overhead.<br />

Chicago’s unusual geological situation, it<br />

was possible through massive infrastructural<br />

work to do the impossible and reverse the<br />

river’s flow away from the lake. The highly<br />

contested project secured clean water for<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> future Chicagoans, but only by<br />

redirecting the negative impact <strong>of</strong> the city’s<br />

success onto others.<br />

1909. Traffic on Dearborn and Randolph.<br />

Chicago has always been a logistics center.<br />

Historically overlaid networks <strong>of</strong> water, rail,<br />

highway, and air travel make today’s city a<br />

major node in the vast systems <strong>of</strong> global<br />

commerce. More than natural forces, the<br />

flow <strong>of</strong> goods and people have shaped the<br />

metropolis’s architecture and landscape. At<br />

the turn <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century the city <strong>of</strong><br />

trade turned hypertrophic: life in Chicago’s<br />

center reached an unprecedented, even<br />

notorious, density. Later decades, however,<br />

would demonstrate that urban development<br />

is not unidirectional, but involves cycles <strong>of</strong><br />

densification and disaggregation, <strong>of</strong> ebb and<br />

flow, over the life <strong>of</strong> the city.<br />

1909. Plan <strong>of</strong> Chicago. Co-authored by<br />

Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett, the<br />

Plan <strong>of</strong> Chicago challenged the non-hierarchical<br />

grid on which the city had grown,<br />

proposing instead a Baroque composition <strong>of</strong><br />

plazas, avenues, and parks arranged symmetrically<br />

around an artificial harbor and<br />

civic center. Though many elements were<br />

never realized, the plan articulated far-reaching<br />

goals that guided Chicago’s development<br />

throughout the twentieth century: the preservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the lakefront for public use, the<br />

expansion <strong>of</strong> parks and forest preserves, and<br />

the creation <strong>of</strong> cultural centers. The Plan<br />

demonstrates that the importance <strong>of</strong> utopian<br />

visions rests not in the details <strong>of</strong> their execution<br />

but in their power to direct the course <strong>of</strong><br />

metropolitan development.<br />

109<br />

17 January 1900. Reversing the River. The<br />

city thrummed with work and life, and the<br />

Chicago River ran through it all, transporting<br />

livestock, grain, and lumber, but also<br />

dumping waste into Lake Michigan, the<br />

city’s supply <strong>of</strong> fresh water. Outbreaks <strong>of</strong><br />

typhoid became increasingly common as the<br />

industrial city sickened itself. Yet, technology<br />

also provided a solution (<strong>of</strong> sorts): given<br />

14 February 1929. St. Valentine’s Day<br />

Massacre. Prohibition brought celebrity,<br />

riches, and violence to Chicago gangland<br />

bosses like Al Capone and Bugs Moran,<br />

whose rival factions controlled the city’s<br />

booze traffic, brothels, and casinos. With its<br />

conspiracy theories, complicit cops, and suspects<br />

who went uncharged, the St. Valentine’s<br />

Chicago<br />

Chicago