- Page 1 and 2:

Gravitational Shielding Research Th

- Page 3 and 4:

Search - Finance Home - Yahoo! - He

- Page 5 and 6:

NEWS SPORT WEATHER WORLD SERVICE A-

- Page 7 and 8:

CATEGORIES TV RADIO COMMUNICATE WHE

- Page 9 and 10:

low graphics version | feedback | h

- Page 11 and 12:

low graphics version | feedback | h

- Page 13 and 14:

Front Page UK World Business Sci/Te

- Page 15 and 16:

CATEGORIES TV RADIO COMMUNICATE WHE

- Page 17 and 18:

Front Page World UK UK Politics Bus

- Page 19 and 20:

Log In Log Out Help Feedback My Acc

- Page 21:

were detailed in JDW 24 July. "Ther

- Page 25 and 26:

By treating the triangular shape as

- Page 27 and 28:

produce a levitation effect. This t

- Page 29:

The Cook Inertial Propulsion unit b

- Page 38:

Lending possible credence to that a

- Page 41 and 42:

Yet, even VentureStar, which if

- Page 43 and 44:

eally only touching on the make or

- Page 50 and 51:

Log In Log Out Help Feedback My Acc

- Page 52 and 53:

hypersonic aerodynamics, particular

- Page 54 and 55:

Recent revelations that BAe is esta

- Page 62 and 63:

Log In Log Out Help Feedback My Acc

- Page 64 and 65:

In 2010: Odyssey II, published in 1

- Page 66 and 67:

technology, fibre optics, tactical

- Page 68 and 69:

Drawing: Los Alamos free electron l

- Page 70 and 71:

Lending possible credence to that a

- Page 72 and 73:

fundamental laws of physics. "The t

- Page 74 and 75:

that had little relationship to the

- Page 76 and 77:

(c)2002 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 78 and 79:

(c)2002 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 80 and 81:

(c)2002 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 82 and 83:

(c)2002 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 84 and 85:

Copyright© 1997, American Institut

- Page 86 and 87:

Copyright© 1997, American Institut

- Page 88 and 89:

Copyright© 1997, American Institut

- Page 90 and 91:

Copyright© 1997, American Institut

- Page 92 and 93:

was highly questioned Copyright© 1

- Page 94 and 95:

Copyright© 1997, American Institut

- Page 96 and 97:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 98 and 99:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 100 and 101:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 102 and 103:

EXPLORATION OF ANOMALOUS GRAVITY EF

- Page 104 and 105:

As aerospace engineers we deal more

- Page 106 and 107:

( DxB) ∂ fH = , (2) ∂t where D

- Page 108 and 109:

d φ = KG (8) c dM The sensitivity

- Page 110 and 111:

- axis) of each chart refers to the

- Page 112 and 113:

non-EM modulated tests on the masse

- Page 114 and 115:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 116 and 117:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 118 and 119:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 120 and 121:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 122 and 123:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 124 and 125:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 126 and 127:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 128 and 129:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 130 and 131:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 132 and 133:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 134 and 135:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 136 and 137:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 138 and 139:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 140 and 141:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 142 and 143:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 144 and 145:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 146 and 147:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 148 and 149:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 150 and 151:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 152 and 153:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 154 and 155:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 156 and 157:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 158 and 159:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 160 and 161:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 162 and 163:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 164 and 165:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 166 and 167:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 168 and 169:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 170 and 171:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 172 and 173:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 174 and 175:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 176 and 177:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 178 and 179:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 180 and 181:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 182 and 183:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 184 and 185:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 186 and 187:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 188 and 189:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 190 and 191:

c)2001 American Institute of Aerona

- Page 192 and 193:

c)2001 American Institute

- Page 194 and 195:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 196 and 197:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 198 and 199:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 200 and 201:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 202 and 203:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 204 and 205:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 206 and 207:

(c)2001 American Institute

- Page 208 and 209:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 210 and 211:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 212 and 213:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 214 and 215:

(c)2001 American Institute

- Page 216 and 217:

(c)2001 American Institute

- Page 218 and 219:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 220 and 221:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 222 and 223:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 224 and 225:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 226 and 227:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 228 and 229:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 230 and 231:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 232 and 233:

(c)2001 American Institute

- Page 234 and 235:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 236 and 237:

(c)2001 American Institute

- Page 238 and 239:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 240 and 241:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 242 and 243:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 244 and 245:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 246 and 247:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 248 and 249:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 250 and 251:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 252 and 253:

(c)l999 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 254 and 255:

BREAKTHROUGH PROPULSION PHYSICS RES

- Page 256 and 257:

PROGRAM PRIORITIES To simultaneousl

- Page 258 and 259:

STATUS AND DIRECTION A government s

- Page 260 and 261:

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Public re

- Page 262 and 263:

Recent calculations have indicated

- Page 264 and 265:

Casimir force has only been compute

- Page 266 and 267:

Cavity width 125 nm Cavity wall 245

- Page 268 and 269:

Also shown for comparison, is the c

- Page 270 and 271:

AIAA-2001-3906 SEARCH FOR EFFECTS O

- Page 272 and 273:

AIAA-2001-3906 Experiment 2 - Time-

- Page 274 and 275:

AIAA-2001-3906 Resonance - 0 flow R

- Page 276 and 277:

AIAA-2001-3906 Einstein Rocket -- E

- Page 278 and 279:

Tests of Mach's Principle with a Me

- Page 280 and 281:

we note that Woodward [4] has made

- Page 282 and 283:

and their tensioning mechanism. Ele

- Page 284 and 285:

Conclusion The test of Mach’s pri

- Page 286 and 287:

velocity of the “front” that mu

- Page 288 and 289:

Fortunately, recent advances in non

- Page 290 and 291:

The time difference between two wel

- Page 292 and 293:

impinging at normal incident on a m

- Page 294 and 295:

sooner than his challenger. Interes

- Page 296 and 297:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 298 and 299:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 300 and 301:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 302 and 303:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 304 and 305:

(c)2001 American Institute of Aeron

- Page 306 and 307:

Register or Login: Password: Quick

- Page 308 and 309:

non-empty space¯time with a horizo

- Page 310 and 311:

metric of S-1 takes the form ds 2 =

- Page 312 and 313:

L. Hui Astrophys. J. 519 (1999), p.

- Page 314 and 315:

Register or Login: Password: Quick

- Page 316 and 317:

consistent with the boundary condit

- Page 318 and 319:

classical behaviour is recovered fo

- Page 320 and 321:

Heisenberg's equations for the posi

- Page 322 and 323:

(2K) Fig. 1. Behaviour of Q(t) for

- Page 324 and 325:

5. N.A. Lemos J. Math. Phys. 37 (19

- Page 326 and 327:

arXiv:cond-mat/9701074 v3 16 Sep 19

- Page 328 and 329:

technology involved in the construc

- Page 330 and 331:

3 Operation of the apparatus. Two i

- Page 332 and 333:

following: in a field gradient of 0

- Page 334 and 335:

inner edge of the toroid (5-7 mm fr

- Page 336 and 337:

7 Discussion. The interaction of a

- Page 338 and 339:

8.1 Acknowledgments. The author is

- Page 340 and 341:

High T c materials, fabrication |ge

- Page 342 and 343:

Supporting solenoids |general, fig.

- Page 344 and 345:

Rotating solenoids |general, fig. 3

- Page 346 and 347:

Cryogenic system |general, fig. 51/

- Page 348 and 349:

Disk braking system |general, fig.

- Page 350 and 351:

In two recent experiments [1, 2], P

- Page 352 and 353:

true, must then consist of some kin

- Page 354 and 355:

constant turns Eintein gravity into

- Page 356 and 357:

[2] E. Podkletnov and A.D. Levit, G

- Page 358 and 359:

Proposal for the Experimental Detec

- Page 360 and 361:

Non-detection of the effect would a

- Page 362 and 363:

system of units to another rather t

- Page 364 and 365:

is not SC, and is composed of norma

- Page 366 and 367:

the rest of the SC). This would sho

- Page 368 and 369:

cylinder has its long axis oriented

- Page 370 and 371:

(24) s = Iω where ω is the spin a

- Page 372 and 373:

established. For ease of experiment

- Page 374 and 375:

lowered into the chamber, alternati

- Page 376 and 377:

T < Tc n n T > Tc n 0 Table 1: Inte

- Page 378 and 379:

a gravitational BCS type theory is

- Page 380 and 381:

III Gravitational London Equations

- Page 382 and 383:

VI Conclusion More significant than

- Page 384 and 385:

UTF-367/96 Jan 1996 arXiv:supr-con/

- Page 386 and 387:

case). To sketch our model - althou

- Page 388 and 389:

The constants k and λ are related

- Page 390 and 391:

UTF-368/96 Jan 1996 Role of a ”Lo

- Page 392 and 393:

mention its scale behaviour and two

- Page 394 and 395:

average out. If µ denotes the ener

- Page 396 and 397:

We expect that when the Montecarlo

- Page 398 and 399:

interact between themselves and pos

- Page 400 and 401:

the system can be expressed as E =

- Page 402 and 403:

〈( ∑ i ( ∑ i = s ij1 ) 2 +

- Page 404 and 405:

as due to the periodic boundary con

- Page 406 and 407:

[1] M.J.G. Veltman, in Methods in f

- Page 408 and 409:

J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 8 (1996)

- Page 410 and 411:

Letter to the Editor L447 Figure 2.

- Page 412 and 413:

Letter to the Editor L449 Figure 3.

- Page 414 and 415:

Letter to the Editor L451 Figure 4.

- Page 416 and 417:

Letter to the Editor L453 Kato R, E

- Page 418 and 419:

The behavior of a Bose condensate -

- Page 420 and 421:

indices of the field must be effect

- Page 422 and 423:

purely gravitational cosmological t

- Page 424 and 425:

(Note that for solutions of (12) on

- Page 426 and 427:

effects can arise. Both characteris

- Page 428 and 429:

density, there will be a thin layer

- Page 430 and 431:

“Mettler 300” scale (300 g full

- Page 432 and 433:

any work on it and thus does not fe

- Page 434 and 435:

[13] H.W. Hamber and R.M. Williams,

- Page 436 and 437:

Appendix: earlier setup. Our first

- Page 438 and 439:

FIGURE CAPTIONS 1. Typical double-w

- Page 440 and 441:

6. Detection system for the demonst

- Page 442 and 443:

Engineering Analysis of the Podklet

- Page 444 and 445:

Magnetic Flux Lines around 1/2 of t

- Page 446 and 447:

From a Relativistic Phenomenology o

- Page 448 and 449:

1. Introduction In this paper we pr

- Page 450 and 451:

(Rubin 1993). In fact, throughout t

- Page 452 and 453:

Lastly, if we consider a theory of

- Page 454 and 455:

3. The Lie conformal pseudogroup as

- Page 456 and 457:

ρ s σ(X, Y ) = ρ ic (X, Y ) −

- Page 458 and 459:

and ˆf ˆρ = ˆρ. (17) In the la

- Page 460 and 461:

Thus, at the sheafs level, the non-

- Page 462 and 463:

that µ may be considered as an Abr

- Page 464 and 465:

Definition 2 We define the r-th Spe

- Page 466 and 467:

Finally, we also have [D 1 , D 2 ]

- Page 468 and 469:

4. The potentials of interaction an

- Page 470 and 471:

where i Y is the interior product b

- Page 472 and 473:

such as ∀ξ k+1 , η k+1 ∈ J k+

- Page 474 and 475:

5.2. The gravitational and electrom

- Page 476 and 477:

This might be (?) an illustration o

- Page 478 and 479:

One uses a rather classical method

- Page 480 and 481:

⎧ ⎪⎨ φ µ (α) = − 1 µ,k

- Page 482 and 483:

ther their real parts, nor their im

- Page 484 and 485:

evolution. In some ways as G. Deleu

- Page 486 and 487:

Pommaret, J.-F. 1995 Suites Differe

- Page 488 and 489:

2 Introduction The discovery of sup

- Page 490 and 491:

4 depressed by a magnetic field [12

- Page 492 and 493:

6 symmetry for the cuprates. Surpri

- Page 494 and 495:

8 metallic ρ(Τ) α T n with n > 1

- Page 496 and 497:

10 pseudogap, two dimensional (2D)

- Page 498 and 499:

12 the hole-doped and electron-dope

- Page 500 and 501:

14 An example of recent progress in

- Page 502 and 503:

16 crystals of these materials [104

- Page 504 and 505:

18 Acknowledgments Assistance in pr

- Page 506 and 507:

20 [22] M. T. Béal-Monod and K. Ma

- Page 508 and 509:

22 [59] A. V. Puchkov, P. Fournier,

- Page 510 and 511:

24 [94] A. G. Sun, A. Truscott, A.

- Page 512 and 513:

26 Table caption Table 1. (a) Some

- Page 514 and 515:

28 Fig. 8. Schematic phase diagram

- Page 516:

30 Table 1. (a) Some important clas

- Page 532 and 533:

wave (7). A background discussion o

- Page 534 and 535:

Gravitation shielding properties of

- Page 536 and 537:

A combination of two different crys

- Page 538 and 539:

3 records selected from Compendex f

- Page 540 and 541:

8. Accession Number: 4 Title:Anti-g

- Page 542 and 543:

Language: English. Document type: J

- Page 544 and 545:

4. Accession Number: 1924832 Title:

- Page 546 and 547:

6. Accession Number: 1171584 Title:

- Page 548 and 549:

4 records selected from Compendex f

- Page 550 and 551:

Full Text Options Access Electronic

- Page 552 and 553:

Take your sex life places it’s ne

- Page 554 and 555:

Pitt physicist offers spin on a uni

- Page 556 and 557:

and his son suffered from mental il

- Page 558 and 559:

that doesn't necessarily mean it do

- Page 560:

But science is constantly doing thi

- Page 566 and 567:

M. Agop et al. / Physica C 339 (200

- Page 568 and 569:

M. Agop et al. / Physica C 339 (200

- Page 570 and 571:

the gravitational ®eld by means of

- Page 572 and 573:

M. Agop et al. / Physica C 339 (200

- Page 579 and 580:

ScienceDirect - Technol Rep Tohoku

- Page 581 and 582:

New Scientist The World's No.1 Scie

- Page 583 and 584:

New Scientist The World's No.1 Scie

- Page 585 and 586:

New Scientist---Antigravity *See up

- Page 587 and 588:

unaffected by an inch-thick steel p

- Page 589 and 590:

Polarizable-Vacuum (PV) representat

- Page 591 and 592:

A. Velocity of Light in a Vacuum of

- Page 593 and 594:

From the reciprocal of Eq. (10) we

- Page 595 and 596:

III. CLASSICAL EXPERIMENTAL TESTS O

- Page 597 and 598:

⎡ v L ≈ c ⎢ 1 − 2GM 1 ⎣

- Page 599 and 600:

d 2 u dθ + u = GMm 2 O e 2GMu c2 +

- Page 601 and 602:

IV. COUPLED MATTER-FIELD EQUATIONS

- Page 603 and 604:

B. General Matter-Field Equations

- Page 605 and 606:

or 2 GM rc 2 K = e = GM rc 2 K = e

- Page 607 and 608:

Comparison of Eqns. (70) - (71) wit

- Page 609 and 610:

Table Metric Effects in the Polariz

- Page 611:

16. H. Goldstein, Classical Mechani

- Page 614 and 615:

Tony Robertson, Staff Engineer for

- Page 616 and 617:

compensation, but with mandatory in

- Page 618 and 619:

Uncontrolled terms: Thermomagnetoel

- Page 620 and 621:

Compilation and Indexing Terms, ©2

- Page 622 and 623:

Дата 20020805 Дата загр

- Page 624 and 625:

устройстве мира - д

- Page 626 and 627:

------------- [http://news.bbc.co.u

- Page 628 and 629:

уважаемых академик

- Page 630 and 631:

сильнейшую головну

- Page 632 and 633:

Именно так воздейс

- Page 634 and 635:

Ученые предложили

- Page 636 and 637:

С самим ученым нам

- Page 638 and 639:

Американское Нацио

- Page 640 and 641:

а на горизонте приз

- Page 642 and 643:

Андрей Самохин В по

- Page 644 and 645:

Мы празднуем своео

- Page 646 and 647:

Мультимедийный вар

- Page 648 and 649:

Но, видя сильный ве

- Page 650 and 651:

Сейчас Поляков дав

- Page 652 and 653:

антигравитационны

- Page 654 and 655:

не отрубил. Обидно:

- Page 656 and 657:

Национальное аэрок

- Page 658 and 659:

долларов. Наверное,

- Page 660 and 661:

последний номер с в

- Page 662 and 663:

"И вдруг, когда молн

- Page 664 and 665:

них магнитный моме

- Page 666 and 667:

Успех эксперимента

- Page 668 and 669:

MSN Home | My MSN | Hotmail | Searc

- Page 670 and 671:

etter than Einstein." Still, Einste

- Page 672 and 673:

The U.S. Antigravity Squadron That

- Page 674 and 675:

Emerging Possibilities for Space Pr

- Page 676 and 677:

Emerging Possibilities for Space Pr

- Page 678 and 679:

Emerging Possibilities for Space Pr

- Page 680 and 681:

Annotated Bibliography (September-O

- Page 682 and 683:

Annotated Bibliography as the "infl

- Page 684 and 685:

Annotated Bibliography In Acta Astr

- Page 686 and 687:

Operation LUSTY near- obsessive bel

- Page 688 and 689:

Operation LUSTY accomplished the ba

- Page 690 and 691:

Operation LUSTY penetrate enemy ter

- Page 692 and 693:

Operation LUSTY his successor, that

- Page 694 and 695:

Operation LUSTY desired effects aga

- Page 696 and 697:

Operation LUSTY 23. Dr. Homerjoe St

- Page 698 and 699:

RS Electrogravitic References RS El

- Page 700 and 701:

RS Electrogravitic References Of al

- Page 702 and 703:

RS Electrogravitic References obser

- Page 704 and 705:

RS Electrogravitic References time

- Page 706 and 707:

RS Electrogravitic References HEP-T

- Page 708 and 709:

RS Electrogravitic References an ar

- Page 710 and 711:

RS Electrogravitic References The R

- Page 712 and 713:

RS Electrogravitic References In: P

- Page 714 and 715:

RS Electrogravitic References . San

- Page 716 and 717:

RS Electrogravitic References 2.3 D

- Page 718 and 719:

RS Electrogravitic References -- Ri

- Page 720 and 721:

RS Electrogravitic References from

- Page 722 and 723:

RS Electrogravitic References and G

- Page 724 and 725:

RS Electrogravitic References From:

- Page 726 and 727:

RS Electrogravitic References scien

- Page 728 and 729:

RS Electrogravitic References the a

- Page 730 and 731:

RS Electrogravitic References MAGNE

- Page 732 and 733:

RS Electrogravitic References AUTHO

- Page 734 and 735:

RS Electrogravitic References F: We

- Page 736 and 737:

RS Electrogravitic References "Grav

- Page 738 and 739:

RS Electrogravitic References Congr

- Page 740 and 741:

RS Electrogravitic References Revol

- Page 742 and 743:

RS Electrogravitic References Autho

- Page 744 and 745:

RS Electrogravitic References b. Ci

- Page 746 and 747:

RS Electrogravitic References Znida

- Page 748 and 749:

RS Electrogravitic References force

- Page 750 and 751:

RS Electrogravitic References Kidd,

- Page 752 and 753:

RS Electrogravitic References Galli

- Page 754 and 755:

RS Electrogravitic References COPYR

- Page 756 and 757:

RS Electrogravitic References Title

- Page 758 and 759:

RS Electrogravitic References impre

- Page 760 and 761:

RS Electrogravitic References and,

- Page 762 and 763:

RS Electrogravitic References GENER

- Page 764 and 765:

RS Electrogravitic References acces

- Page 766 and 767:

RS Electrogravitic References altho

- Page 768 and 769:

RS Electrogravitic References appea

- Page 770 and 771:

RS Electrogravitic References withi

- Page 772 and 773:

RS Electrogravitic References follo

- Page 774 and 775:

RS Electrogravitic References Antim

- Page 776 and 777:

RS Electrogravitic References conve

- Page 778 and 779:

RS Electrogravitic References -----

- Page 780 and 781:

RS Electrogravitic References -----

- Page 782 and 783:

RS Electrogravitic References AUTHO

- Page 784 and 785:

RS Electrogravitic References In: P

- Page 786 and 787:

RS Electrogravitic References suppr

- Page 788 and 789:

RS Electrogravitic References mater

- Page 790 and 791:

RS Electrogravitic References AUTHO

- Page 792 and 793:

RS Electrogravitic References TITLE

- Page 794 and 795:

RS Electrogravitic References R. H.

- Page 796 and 797:

RS Electrogravitic References M. Ku

- Page 798 and 799:

RS Electrogravitic References of th

- Page 800 and 801:

RS Electrogravitic References FORMA

- Page 802 and 803:

RS Electrogravitic References Lette

- Page 804 and 805:

RS Electrogravitic References Dirty

- Page 806 and 807:

RS Electrogravitic References AUTHO

- Page 808 and 809:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 810 and 811:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 812 and 813:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 814 and 815:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 816 and 817:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 818 and 819:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 820 and 821:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 822 and 823:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 824 and 825:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 826 and 827:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 828 and 829:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 830 and 831:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 832 and 833:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 834 and 835:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 836 and 837:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 838 and 839:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 840 and 841:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 842 and 843:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 844 and 845:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 846 and 847:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 848 and 849:

Electrogravitics Systems: An examin

- Page 850 and 851:

ELECTROGRAVITICS SYSTEMS REPORTS ON

- Page 852 and 853:

CONTENTS Foreword 4 Elizabeth Rausc

- Page 854 and 855:

Accelerator Center, Stanford, CA wi

- Page 856:

Introduction, as well as copies of

- Page 861 and 862:

ELECTROGRAVITICS SYSTEMS An examina

- Page 863 and 864:

DISCUSSION Electrogravitics might b

- Page 865 and 866:

particles - that is to say those th

- Page 867 and 868:

interrelationship is a difficulty a

- Page 869 and 870:

electrogravitics. This is one line

- Page 871 and 872:

In 1955 the number of technicians e

- Page 873 and 874:

existence and collisions that give

- Page 875 and 876:

and counterbary. Counterbary is the

- Page 877 and 878:

ANTI-GRAVITATION RESEARCH The basic

- Page 879 and 880:

towards realization of a manned veh

- Page 881 and 882:

ELECTRO-GRAVITIC PROPULSION SITUATI

- Page 883 and 884:

investment is likely to be necessar

- Page 885 and 886:

to its present pitch. Beyond the th

- Page 887 and 888:

ELECTRO-GRAVITICS EFFORT WIDENING C

- Page 889 and 890:

ELECTROSTATIC MOTORS 40

- Page 891 and 892:

THE GRAVITICS SITUATION December 19

- Page 893 and 894:

that no new breakthroughs are neede

- Page 895 and 896:

equipotentials can be made less con

- Page 897 and 898:

laboratory man-hours is necessary o

- Page 899 and 900:

But aviation business is understand

- Page 901 and 902:

HI i GLOSSARY Gravithermals: Thermi

- Page 903 and 904:

Magnetogravitics : Boson Fields: Fe

- Page 905 and 906:

N. Schein, D.M. Haskin and R.G. Cla

- Page 907 and 908:

similar and allied forces the two e

- Page 909 and 910:

This movement is practically linear

- Page 911 and 912:

an assembly of the gravitator cells

- Page 913 and 914:

space were suddenly filled with man

- Page 915 and 916:

and utilizing it in the constructio

- Page 917 and 918:

APPENDIX ffl GRAVITY EFFECTS The or

- Page 919 and 920:

APPENDIX IV A LINK BETWEEN GRAVITAT

- Page 921 and 922:

APPENDIX VI WEIGHT-MASS ANOMALY The

- Page 923 and 924:

ABSTRACT Based on the asymmetry of

- Page 925 and 926:

do not favor such transitions, and

- Page 927 and 928:

THE U.S. ANTIGRAVITY SQUADRON by Pa

- Page 929 and 930:

Clearly, the overseers of black R &

- Page 931 and 932:

The saucers made by Brown have no p

- Page 933 and 934:

supersonic velocities. Also, in his

- Page 935 and 936:

Figure 5. A version of the flying d

- Page 937 and 938:

dielectrics are a likely choice for

- Page 939 and 940:

Figure 7. A side view of the B-2 sh

- Page 941 and 942:

which provides the electrostatic en

- Page 943 and 944:

for linearly accelerating negative

- Page 945 and 946:

Unit, London, February 1956. (Libra

- Page 949 and 950:

100

- Page 951 and 952:

102

- Page 953 and 954:

104

- Page 955 and 956:

106

- Page 957 and 958:

108

- Page 959 and 960:

110

- Page 961 and 962:

112

- Page 963 and 964:

Larry Deavenport is a hobbyist in e

- Page 965 and 966:

various levels and special notice w

- Page 967 and 968:

The Antigravity Research of T. Town

- Page 970 and 971:

Book Review Electrogravitics System

- Page 972:

The Hunt for Zero Point

- Page 975 and 976:

THE HUNT FOR ZERO POINT. Copyright

- Page 978 and 979:

Author's Note and Acknowledgments N

- Page 980 and 981:

Prologue The dust devils swirled ar

- Page 982 and 983:

Prologue xi The troops had been par

- Page 984 and 985:

Chapter 1 From the heavy-handed sty

- Page 986 and 987:

NICK COOK 3 Martin Aircraft Company

- Page 988 and 989:

NICK COOK 5 In the course of a deca

- Page 990 and 991:

NICK COOK 7 "negative weight"—a r

- Page 992 and 993:

NICK COOK 9 process, giving somethi

- Page 994 and 995:

NICK COOK 11 also levitate paper cl

- Page 996 and 997:

Chapter 2 In 1667, Newton mathemati

- Page 998 and 999:

NICK COOK 15 I had no direct eviden

- Page 1000 and 1001:

NICK COOK 17 cupped the receiver, b

- Page 1002 and 1003:

NICK COOK 19 Electrogravitics Syste

- Page 1004 and 1005:

NICK COOK 21 dismiss anything that

- Page 1006 and 1007:

NICK COOK 23 the following year swi

- Page 1008 and 1009:

NICK COOK 25 In this, according to

- Page 1010 and 1011:

NICK COOK 27 "degaussed" the brains

- Page 1012 and 1013:

NICK COOK 29 man responsible for so

- Page 1014 and 1015:

NICK COOK 31 Valone seemed quite un

- Page 1016 and 1017:

NICK COOK 33 model flying saucers b

- Page 1018 and 1019:

NICK COOK 35 trying to put the piec

- Page 1020 and 1021:

NICK COOK 37

- Page 1022 and 1023:

Chapter 4 History doesn't relate th

- Page 1024 and 1025:

NICK COOK 41 something—anything

- Page 1026 and 1027:

NICK COOK 43 Park, Maryland. What w

- Page 1028 and 1029:

NICK COOK 45 integral to most moder

- Page 1030 and 1031:

NICK COOK 47 the most baffling myst

- Page 1032 and 1033:

NICK COOK 49 Lusty files were old a

- Page 1034 and 1035:

NICK COOK 51 In the spring of 1941,

- Page 1036 and 1037:

NICK COOK 53 near Breslau under the

- Page 1038 and 1039:

NICK COOK 55 flying bomb designed t

- Page 1040 and 1041:

NICK COOK 57 his death in November

- Page 1042 and 1043:

NICK COOK 59 had developed a revolu

- Page 1044 and 1045:

NICK COOK 61 If there was any sense

- Page 1046 and 1047:

NICK COOK 63 A year after the war e

- Page 1048 and 1049:

NICK COOK 65 yet kicked in and my b

- Page 1050 and 1051:

NICK COOK 67 microfilmed documentat

- Page 1052 and 1053:

NICK COOK 69 reports made by aircre

- Page 1054 and 1055:

NICK COOK 71

- Page 1056 and 1057:

NICK COOK 73 What had I actually le

- Page 1058 and 1059:

NICK COOK 75 contract with the Avro

- Page 1060 and 1061:

NICK COOK 77 been built, but flight

- Page 1062 and 1063:

NICK COOK 79 inaccessible to more t

- Page 1064 and 1065:

NICK COOK 81 an antigravity effect

- Page 1066 and 1067:

NICK COOK 83 down the aircraft's la

- Page 1068 and 1069:

NICK COOK 85 principally to see if

- Page 1070 and 1071:

NICK COOK 87 It was then that I rea

- Page 1072 and 1073:

NICK COOK 89 started talking about

- Page 1074 and 1075:

NICK COOK 91 don't really have a ta

- Page 1076 and 1077:

Chapter 9 A larger-than-life depict

- Page 1078 and 1079:

NICK COOK 95 But ASTP did not end t

- Page 1080 and 1081:

NICK COOK 97 questions churned, as

- Page 1082 and 1083:

NICK COOK 99 He paused and rubbed t

- Page 1084 and 1085:

NICK COOK 101 propulsive antigravit

- Page 1086 and 1087:

NICK COOK 103 down. He was abandone

- Page 1088 and 1089:

NICK COOK 105 * * * On the flight d

- Page 1090 and 1091:

NICK COOK 107 reaction to the Podkl

- Page 1092 and 1093:

NICK COOK 109 Cleveland and, believ

- Page 1094 and 1095:

NICK COOK 111 These vibrating field

- Page 1096 and 1097:

NICK COOK 113 Union, using nothing

- Page 1098 and 1099:

Chapter 11 If antigravity had been

- Page 1100 and 1101:

NICK COOK 117 Stealth had the power

- Page 1102 and 1103:

NICK COOK 119 missions in the late

- Page 1104 and 1105:

NICK COOK 121 disclosure, however,

- Page 1106 and 1107:

Chapter 12 I'd been aware of rumors

- Page 1108 and 1109:

NICK COOK 125 Fellow of the Royal A

- Page 1110 and 1111:

NICK COOK 127 accurate total budget

- Page 1112 and 1113:

NICK COOK 129 F-l 17 A, composed of

- Page 1114 and 1115:

Below: Alleged photograph of Rudolp

- Page 1116 and 1117:

Left: John Frost. Below: A cutaway

- Page 1118 and 1119:

Above: British Aerospace's concept

- Page 1120 and 1121:

Above: The Northrop Grumman B-2 Ste

- Page 1122 and 1123:

Above: Map showing key California-b

- Page 1125 and 1126:

Below: SS General Hans Kammler - th

- Page 1127 and 1128:

Left: Bob Widmer, chief designer of

- Page 1129 and 1130:

Metal ingots 'disrupted' by the Hut

- Page 1131 and 1132:

132 The Hunt for Zero Point could s

- Page 1133 and 1134:

134 The Hunt for Zero Point impossi

- Page 1135 and 1136:

136 The Hunt for Zero Point Lockhee

- Page 1137 and 1138:

138 The Hunt for Zero Point The man

- Page 1139 and 1140:

140 The Hunt for Zero Point deduced

- Page 1141 and 1142: 142 The Hunt for Zero Point Brown's

- Page 1143 and 1144: 144 The Hunt for Zero Point Soviet

- Page 1145 and 1146: Chapter 14 There were two final way

- Page 1147 and 1148: 148 The Hunt for Zero Point all our

- Page 1149 and 1150: 150 The Hunt for Zero Point encoura

- Page 1151 and 1152: 152 The Hunt for Zero Point Just as

- Page 1153 and 1154: 154 The Hunt for Zero Point the A-4

- Page 1155 and 1156: 156 The Hunt for Zero Point done an

- Page 1157 and 1158: 158 The Hunt for Zero Point as offe

- Page 1159 and 1160: Chapter 16 According to Agoston, Ka

- Page 1161 and 1162: 162 The Hunt for Zero Point not, th

- Page 1163 and 1164: 164 The Hunt for Zero Point from Ka

- Page 1165 and 1166: 166 The Hunt for Zero Point mountai

- Page 1167 and 1168: 168 The Hunt for Zero Point service

- Page 1169 and 1170: Chapter 17 I entered the complex fr

- Page 1171 and 1172: 172 The Hunt for Zero Point had spa

- Page 1173 and 1174: 174 The Hunt for Zero Point signed

- Page 1175 and 1176: 176 The Hunt for Zero Point and int

- Page 1177 and 1178: 178 The Hunt for Zero Point have ig

- Page 1179 and 1180: 180 The Hunt for Zero Point radiati

- Page 1181 and 1182: 182 The Hunt for Zero Point to use

- Page 1183 and 1184: 184 The Hunt for Zero Point "And th

- Page 1185 and 1186: 186 The Hunt for Zero Point activit

- Page 1187 and 1188: 188 The Hunt for Zero Point the rea

- Page 1189 and 1190: 190 The Hunt for Zero Point untimel

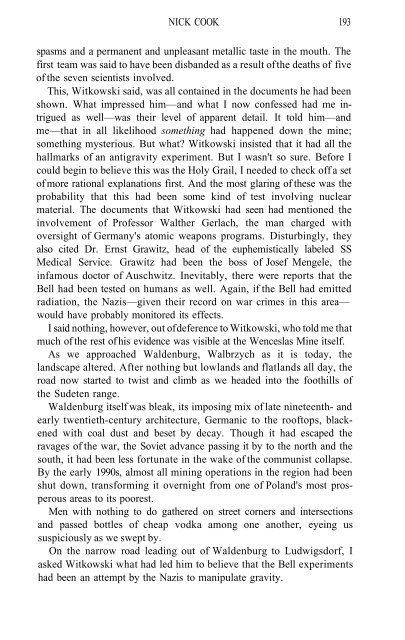

- Page 1191: 192 The Hunt for Zero Point violet

- Page 1195 and 1196: 196 The Hunt for Zero Point Even th

- Page 1197 and 1198: 198 The Hunt for Zero Point That ni

- Page 1199 and 1200: 200 The Hunt for Zero Point impenet

- Page 1201 and 1202: Chapter 21 The next day, I was back

- Page 1203 and 1204: 204 The Hunt for Zero Point Many of

- Page 1205 and 1206: 206 The Hunt for Zero Point appeare

- Page 1207 and 1208: 208 The Hunt for Zero Point One suc

- Page 1209 and 1210: 210 The Hunt for Zero Point natural

- Page 1211 and 1212: 212 The Hunt for Zero Point

- Page 1213 and 1214: 214 The Hunt for Zero Point notion,

- Page 1215 and 1216: 216 The Hunt for Zero Point is busi

- Page 1217 and 1218: 218 The Hunt for Zero Point during

- Page 1219 and 1220: 220 The Hunt for Zero Point Via Sch

- Page 1221 and 1222: 222 The Hunt for Zero Point compres

- Page 1223 and 1224: 224 The Hunt for Zero Point detaile

- Page 1225 and 1226: 226 The Hunt for Zero Point U.S. si

- Page 1227 and 1228: 228 The Hunt for Zero Point the bes

- Page 1229 and 1230: Chapter 23 Viewed from the back of

- Page 1231 and 1232: 232 The Hunt for Zero Point The ide

- Page 1233 and 1234: 234 The Hunt for Zero Point It was

- Page 1235 and 1236: 236 The Hunt for Zero Point spin-of

- Page 1237 and 1238: 238 The Hunt for Zero Point metal p

- Page 1239 and 1240: 240 The Hunt for Zero Point Martin,

- Page 1241 and 1242: Chapter 24 The flight was several h

- Page 1243 and 1244:

244 The Hunt for Zero Point morning

- Page 1245 and 1246:

246 The Hunt for Zero Point I was i

- Page 1247 and 1248:

248 The Hunt for Zero Point was one

- Page 1249 and 1250:

250 The Hunt for Zero Point not, as

- Page 1251 and 1252:

252 The Hunt for Zero Point science

- Page 1253 and 1254:

254 The Hunt for Zero Point confirm

- Page 1255 and 1256:

256 The Hunt for Zero Point Einstei

- Page 1257 and 1258:

258 The Hunt for Zero Point had bel

- Page 1259 and 1260:

260 The Hunt for Zero Point theory

- Page 1261 and 1262:

262 The Hunt for Zero Point Hutchis

- Page 1263 and 1264:

264 The Hunt for Zero Point later,

- Page 1265 and 1266:

266 The Hunt for Zero Point Hutchis

- Page 1267 and 1268:

268 The Hunt for Zero Point objects

- Page 1269 and 1270:

270 The Hunt for Zero Point "When y

- Page 1271 and 1272:

272 The Hunt for Zero Point I could

- Page 1273 and 1274:

274 The Hunt for Zero Point that wo

- Page 1275 and 1276:

276 The Hunt for Zero Point orbitin

- Page 1277 and 1278:

278 The Hunt for Zero Point enough

- Page 1279 and 1280:

280 The Hunt for Zero Point Lucas,

- Page 1281 and 1282:

Index Page numbers of illustrations

- Page 1283 and 1284:

284 Index Brown, Thomas Townsend (c

- Page 1285 and 1286:

286 Index Gunston, Bill, 124-25 Gyr

- Page 1287 and 1288:

288 Index NASA (cont'd) Marshall Sp

- Page 1289 and 1290:

290 Index Tesla, Nikola, 258-60 Tun

- Page 1291:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Nick Cook is the A