Tape Recording Magazine - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Tape Recording Magazine - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Tape Recording Magazine - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

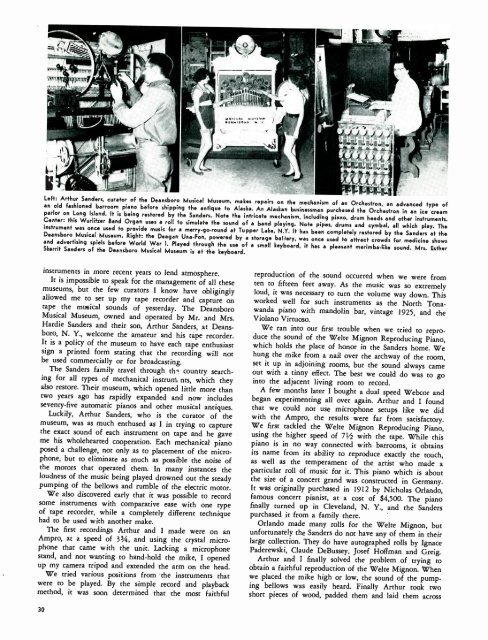

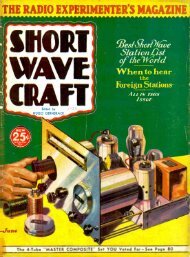

Left: Arthur Sanders, curator of the Deansboro Musical Museum, makes repairs on the mechanism of an Orchestron, an advanced type of<br />

an old fashioned barroom piano before shipping the antique fo Alaska. An Alaskan businessman purchased the Orchestron in an ice cream<br />

parlor on Long Island. It is being restored by the Sanders. Note the intricate mechanism, including piano, drum heads and other instruments.<br />

Center: this Wurlitzer Band Organ uses a roll to simulate the sound of a band playing. Note pipes, drums and cymbal, all which play. The<br />

instrument was once used to provide music for a<br />

merry -go -round at Tupper Lake, N.Y. It has been<br />

Deansboro<br />

completely<br />

Musical<br />

restored<br />

Museum.<br />

by the<br />

Right:<br />

Sanders<br />

the Deagan<br />

at the<br />

Una -Fon, powered by a storage battery, was once used fo attract crowds for medicine shows<br />

and advertising spiels before World War I. Played through the use of a<br />

Skerrit Sanders of the Deansboro Musical Museum is at the keyboard.<br />

small keyboard, it has a pleasant marimba -like sound. Mrs. Esther<br />

instruments in more recent years to lend atmosphere.<br />

It is impossible to speak for the management of all these<br />

museums, but the few curators I know have obligingly<br />

allowed me to set up my tape recorder and capture on<br />

tape the musical sounds of yesterday. The Deansboro<br />

Musical Museum, owned and operated by Mr. and Mrs.<br />

Hardie Sanders and their son, Arthur Sanders, at Deans -<br />

boro, N. Y., welcome the amateur and his tape recorder.<br />

It is a policy of the museum to have each tape enthusiast<br />

sign a printed form stating that the recording will not<br />

be used commercially or for broadcasting.<br />

The Sanders family travel through th- country searching<br />

for all types of mechanical instrum nts, which they<br />

also restore. Their museum, which opened little more than<br />

two years ago has rapidly expanded and now includes<br />

seventy-five automatic pianos and other musical antiques.<br />

Luckily, Arthur Sanders, who is the curator of the<br />

museum, was as much enthused as I in trying to capture<br />

the exact sound of each instrument on tape and he gave<br />

me his wholehearted cooperation. Each mechanical piano<br />

posed a challenge, not only as to placement of the microphone,<br />

but to eliminate as much as possible the noise of<br />

the motors that operated them. In many instances the<br />

loudness of the music being played drowned out the steady<br />

pumping of the bellows and rumble of the electric motor.<br />

We also discovered early that it was possible to record<br />

some instruments with comparative ease with one type<br />

of tape recorder, while a completely different technique<br />

had to be used with another make.<br />

The first recordings Arthur and I made were on an<br />

Ampro, at a speed of 33/, and using the crystal microphone<br />

that came with the unit. Lacking a microphone<br />

stand, and not wanting to hand -hold the mike, I opened<br />

up my camera tripod and extended the arm on the head.<br />

We tried various positions from the instruments that<br />

were to be played. By the simple record and playback<br />

method, it was soon determined that the most faithful<br />

reproduction of the sound occurred when we were from<br />

ten to fifteen feet away. As the music was so extremely<br />

loud, it was necessary to turn the volume way down. This<br />

worked well for such instruments as the North Tonawanda<br />

piano with mandolin bar, vintage 1925, and the<br />

Violano Virtuoso.<br />

We ran into our first trouble when we tried to reproduce<br />

the sound of the Weite Mignon Reproducing Piano,<br />

which holds the place of honor in the Sanders home. We<br />

hung the mike from a nail over the archway of the room,<br />

set it up in adjoining rooms, but the sound always came<br />

out with a tinny effect. The best we could do was to go<br />

into the adjacent living room to record.<br />

A few months later I bought a dual speed Webcor and<br />

began experimenting all over again. Arthur and I found<br />

that we could not use microphone setups like we did<br />

with the Ampro, the results were far from satisfactory.<br />

We first tackled the Welte Mignon Reproducing Piano,<br />

using the higher speed of 71/2 with the tape. While this<br />

piano is in no way connected with barrooms, it obtains<br />

its name from its ability to reproduce exactly the touch,<br />

as well as the temperament of the artist who made a<br />

particular roll of music for it. This piano which is about<br />

the size of a concert grand was constructed in Germany.<br />

It was originally purchased in 1912 by Nicholas Orlando,<br />

famous concert pianist, at a cost of $4,500. The piano<br />

finally turned up in Cleveland, N. Y., and the Sanders<br />

purchased it from a family there.<br />

Orlando made many rolls for the Wette Mignon, but<br />

unfortunately the Sanders do not have any of them in their<br />

large collection. They do have autographed rolls by Ignace<br />

Paderewski, Claude DeBussey, Josef Hoffman and Greig.<br />

Arthur and I finally solved the problem of trying to<br />

obtain a faithful reproduction of the Welte Mignon. When<br />

we placed the mike high or low, the sound of the pumping<br />

bellows was easily heard. Finally Arthur took two<br />

short pieces of wood, padded them and laid them across<br />

30