- Page 1 and 2: NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS‐PI

- Page 3 and 4: Pacific Islands Fisheries Science C

- Page 5 and 6: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many subject matter

- Page 7 and 8: CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..........

- Page 9 and 10: 5.5 Assessing the Critical Risk Thr

- Page 11 and 12: 7.11 Genus Porites ................

- Page 13 and 14: LIST OF FIGURES Figure ES-1. Exampl

- Page 15 and 16: Figure 3.3.6. The impacts of diseas

- Page 17 and 18: Figure 6.5.3. Distribution of point

- Page 19 and 20: Figure 7.5.10. Distribution of poin

- Page 21 and 22: Figure 7.5.54. Distribution of poin

- Page 23 and 24: Figure 7.6.8. Distribution of point

- Page 25 and 26: Figure 7.9.28. Montipora verrilli d

- Page 27 and 28: Figure 7.13.7. Leptoseris yabei dis

- Page 29 and 30: Figure 7.18.12. Distribution of poi

- Page 31 and 32: Figure 7.24.8. Distribution of poin

- Page 33 and 34: ACRONYMS AAAS AGGRA AIMS AR4 BRT CA

- Page 35 and 36: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On October 20, 20

- Page 37 and 38: Figure ES-2. Summary of votes talli

- Page 39 and 40: xxxvii

- Page 41 and 42: 1. INTRODUCTION On October 20, 2009

- Page 43 and 44: The NMFS must base its determinatio

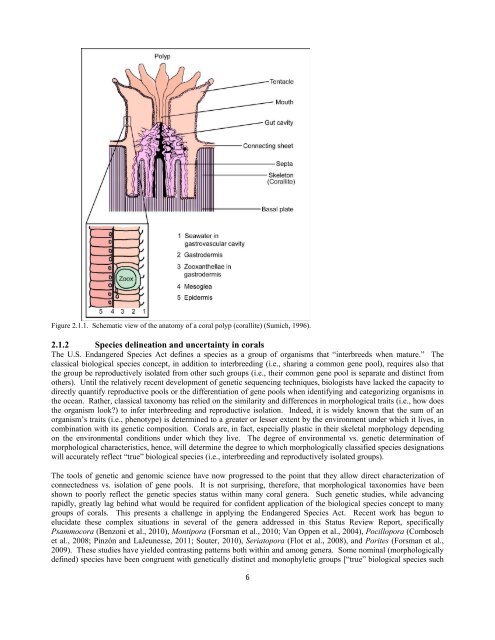

- Page 45: 2. GENERAL BACKGROUND ON CORALS AND

- Page 49 and 50: Figure 2.2.1. Diversity of coral li

- Page 51 and 52: on zooplankton can reduce the uptak

- Page 53 and 54: provide net economic benefits of $3

- Page 55 and 56: In some locations, such as Hawai`i,

- Page 57 and 58: Table 2.5.1. Summary of regional co

- Page 59 and 60: 3. THREATS TO CORAL SPECIES 3.1 Hum

- Page 61 and 62: Figure 3.1.1. World population from

- Page 63 and 64: 2,500 People per km 2 Reef Area 2,0

- Page 65 and 66: 3.2 Global Climate Change and Large

- Page 67 and 68: 1980), more recent work indicates t

- Page 69 and 70: forces put into place by anthropoge

- Page 71 and 72: 3.2.2.1 Coral bleaching High temper

- Page 73 and 74: Figure 3.2.7. Global map of reef ar

- Page 75 and 76: Figure 3.2.8. Predicted phytoplankt

- Page 77 and 78: The dynamics of carbonate chemistry

- Page 79 and 80: Figure 3.2.14. (Top and middle rows

- Page 81 and 82: other branching corals (Langdon and

- Page 83 and 84: Species Lophelia pertusa (cold wate

- Page 85 and 86: 3.2.3.2. Increased erosion Another

- Page 87 and 88: as sea-level rise proceeds. Greater

- Page 89 and 90: Figure 3.2.19. The impacts of chang

- Page 91 and 92: ecosystems (Garrison et al., 2003).

- Page 93 and 94: chemicals such as pesticides. Eleva

- Page 95 and 96: Figure 3.3.1. The impacts of sedime

- Page 97 and 98:

1999; Thacker et al., 2001) because

- Page 99 and 100:

Other demonstrated sublethal effect

- Page 101 and 102:

3.3.1.4 Salinity impacts Many coral

- Page 103 and 104:

Some evidence show that seawater sa

- Page 105 and 106:

Figure 3.3.6. The impacts of diseas

- Page 107 and 108:

Figure 3.3.7. The impacts of predat

- Page 109 and 110:

Important synergies of corallivory

- Page 111 and 112:

facilitates coral recruitment), and

- Page 113 and 114:

The recent Reefs at Risk Revisited

- Page 115 and 116:

eplenish themselves from distant po

- Page 117 and 118:

eview, the BRT considers tsunami an

- Page 119 and 120:

Figure 3.3.12. Global analysis of r

- Page 121 and 122:

Au`au Channel is a thermocline, a d

- Page 123 and 124:

A very recent independent global an

- Page 125 and 126:

Unapparent effects are another comp

- Page 127 and 128:

4. DEMOGRAPHIC AND SPATIAL FACTORS

- Page 129 and 130:

the same environmental threats (e.g

- Page 131 and 132:

in identifying species in the field

- Page 133 and 134:

4.5.1 Critical Risk Threshold and d

- Page 135 and 136:

Figure 4.5.2. Number of successful

- Page 137 and 138:

(Rasher and Hay, 2010) and can redu

- Page 139 and 140:

5. METHODS 5.1 Overview In evaluati

- Page 141 and 142:

5.6 BRT Voting To estimate the like

- Page 143 and 144:

In establishing the approaches used

- Page 145 and 146:

Figure 6.1.2. Agaricia lamarcki dis

- Page 147 and 148:

Acidification: No specific research

- Page 149 and 150:

6.2 Genus Mycetophyllia (Family Mus

- Page 151 and 152:

Mycetophyllia ferox cover to be con

- Page 153 and 154:

6.3 Genus Dendrogyra (Family Meandr

- Page 155 and 156:

Depth range: Dendrogyra cylindrus h

- Page 157 and 158:

Risk Assessment Figure 6.3.5. Distr

- Page 159 and 160:

Evolutionary and geologic history:

- Page 161 and 162:

Disease: Dichocoenia stokesi has be

- Page 163 and 164:

6.5 Genus Montastraea (Family Favii

- Page 165 and 166:

Figure 6.5. Examples of declining a

- Page 167 and 168:

genetic variability in the molecula

- Page 169 and 170:

6.5.1 Montastraea faveolata Ellis a

- Page 171 and 172:

Risk Assessment Figure 6.5.3. Distr

- Page 173 and 174:

Figure 6.5.5. Montastraea franksi d

- Page 175 and 176:

6.5.3 Montastraea annularis Ellis a

- Page 177 and 178:

Risk Assessment Figure 6.5.10. Dist

- Page 179 and 180:

Figure 7.1.2. Millepora foveolata d

- Page 181 and 182:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.1.3. Distr

- Page 183 and 184:

Family: Milleporidae. Evolutionary

- Page 185 and 186:

Land-based sources of pollution (LB

- Page 187 and 188:

7.2 Genus Heliopora (Class Anthozoa

- Page 189 and 190:

Within federally protected waters,

- Page 191 and 192:

Acidification: No specific research

- Page 193 and 194:

7.3 Genus Pocillopora (Class Anthoz

- Page 195 and 196:

Acidification: One recent study (Ma

- Page 197 and 198:

Figure 7.3.2. Pocillopora danae dis

- Page 199 and 200:

Predation: Pocillopora species are

- Page 201 and 202:

7.3.2 Pocillopora elegans Dana, 186

- Page 203 and 204:

Within federally protected waters,

- Page 205 and 206:

Risk Assessment The nominal candida

- Page 207 and 208:

Central and Indo-Pacific Pocillopor

- Page 209 and 210:

Figure 7.4.3. Seriatopora aculeata

- Page 211 and 212:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.4.4. Distr

- Page 213 and 214:

Life History Acropora are sessile c

- Page 215 and 216:

drop out (Randall and Birkeland, 19

- Page 217 and 218:

Island in the southeastern Pacific

- Page 219 and 220:

Land-based sources of pollution (LB

- Page 221 and 222:

Figure 7.5.8. Acropora acuminata di

- Page 223 and 224:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.5.10. Dist

- Page 225 and 226:

Taxonomy Taxonomic issues: None. Fa

- Page 227 and 228:

Although range expansion was not di

- Page 229 and 230:

7.5.4 Acropora dendrum Bassett-Smit

- Page 231 and 232:

Life History Acropora dendrum is a

- Page 233 and 234:

7.5.5 Acropora donei Veron and Wall

- Page 235 and 236:

Acidification: No specific research

- Page 237 and 238:

7.5.6 Acropora globiceps Dana, 1846

- Page 239 and 240:

Life History Acropora globiceps is

- Page 241 and 242:

7.5.7 Acropora horrida Dana 1846 Fi

- Page 243 and 244:

Life History Acropora horrida is a

- Page 245 and 246:

7.5.8 Acropora jacquelineae Wallace

- Page 247 and 248:

Abundance Abundance of Acropora hor

- Page 249 and 250:

7.5.9 Acropora listeri Brook, 1893

- Page 251 and 252:

Life History Acropora listeri is a

- Page 253 and 254:

7.5.10 Acropora lokani Wallace, 199

- Page 255 and 256:

Life History Acropora lokani is ass

- Page 257 and 258:

7.5.11 Acropora microclados Ehrenbe

- Page 259 and 260:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 261 and 262:

7.5.12 Acropora palmerae Wells, 195

- Page 263 and 264:

Life History Acropora palmerae is a

- Page 265 and 266:

7.5.13 Acropora paniculata Verrill,

- Page 267 and 268:

Abundance Abundance of Acropora pan

- Page 269 and 270:

7.5.14 Acropora pharaonis Milne Edw

- Page 271 and 272:

Abundance Abundance of Acropora pha

- Page 273 and 274:

7.5.15 Acropora polystoma Brook, 18

- Page 275 and 276:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 277 and 278:

7.5.16. Acropora retusa Dana, 1846

- Page 279 and 280:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 281 and 282:

7.5.16 Acropora rudis Rehberg, 1892

- Page 283 and 284:

et al., 2009). While ocean acidific

- Page 285 and 286:

7.5.17 Acropora speciosa Quelch, 18

- Page 287 and 288:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 289 and 290:

7.5.18 Acropora striata Verrill, 18

- Page 291 and 292:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 293 and 294:

7.5.19 Acropora tenella Brook, 1892

- Page 295 and 296:

Disease: In general, Acropora speci

- Page 297 and 298:

7.5.20 Acropora vaughani Wells, 195

- Page 299 and 300:

Threats For each of these possible

- Page 301 and 302:

7.5.21 Acropora verweyi Veron and W

- Page 303 and 304:

A search of published and unpublish

- Page 305 and 306:

Factors that increase the potential

- Page 307 and 308:

Figure 7.6.3. Anacropora puertogale

- Page 309 and 310:

Risk assessment Figure 7.6.4. Distr

- Page 311 and 312:

Figure 7.6.7. Anacropora spinosa di

- Page 313 and 314:

Factors that increase the potential

- Page 315 and 316:

Figure 7.7.3. Astreopora cucullata

- Page 317 and 318:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.7.4. Distr

- Page 319 and 320:

Isopora has recently been considere

- Page 321 and 322:

Acidification: No specific research

- Page 323 and 324:

7.8.2 Isopora cuneata Dana, 1846 Fi

- Page 325 and 326:

U.S. Distribution According to both

- Page 327 and 328:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.8.10. Dist

- Page 329 and 330:

Life History Of the 35 species of M

- Page 331 and 332:

Figure 7.9.3. Montipora angulata di

- Page 333 and 334:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.9.4. Distr

- Page 335 and 336:

Figure 7.9.7. Montipora australiens

- Page 337 and 338:

Factors that increase the potential

- Page 339 and 340:

Global Distribution Global distribu

- Page 341 and 342:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.9.12. Dist

- Page 343 and 344:

Figure 7.9.15. Montipora caliculata

- Page 345 and 346:

Risk Assessment Figure 7.9.16. Dist

- Page 347 and 348:

Taxonomy Taxonomic issues: Importan

- Page 349 and 350:

Land-based sources of pollution (LB

- Page 351 and 352:

7.9.6 Montipora lobulata Bernard, 1

- Page 353 and 354:

(Albright et al., 2010) and is like

- Page 355 and 356:

7.9.7 Montipora patula (/verrili) B

- Page 357 and 358:

Threats Thermal stress: Montipora s

- Page 359 and 360:

7.10 Genus Alveopora (Family Poriti

- Page 361 and 362:

Life History Reproductive character

- Page 363 and 364:

7.10.2 Alveopora fenestrata Lamarck

- Page 365 and 366:

Threats Temperature stress: The gen

- Page 367 and 368:

7.10.3 Alveopora verrilliana Dana,

- Page 369 and 370:

Life History Alveopora verrilliana

- Page 371 and 372:

7.11 Genus Porites 7.11.1 Porites h

- Page 373 and 374:

Threats Temperature stress: Massive

- Page 375 and 376:

7.11.2 Porites napopora Veron, 2000

- Page 377 and 378:

Habitat Habitat: Porites napopora h

- Page 379 and 380:

7.11.3 Porites nigrescens Dana, 184

- Page 381 and 382:

of all other Porites species studie

- Page 383 and 384:

7.11.4 Porites pukoensis Vaughan, 1

- Page 385 and 386:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 387 and 388:

Risk Assessment of Porites clade 1

- Page 389 and 390:

7.12 Genus Psammocora (Family Sider

- Page 391 and 392:

Abundance Abundance of Psammocora s

- Page 393 and 394:

7.13 Genus Leptoseris (Family Agari

- Page 395 and 396:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 397 and 398:

7.13.2 Leptoseris yabei Pillai and

- Page 399 and 400:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 401 and 402:

7.14 Genus Pachyseris 7.14.1 Pachys

- Page 403 and 404:

ased on elevated temperatures and l

- Page 405 and 406:

7.15 Genus Pavona 7.15.1 Pavona bip

- Page 407 and 408:

Threats Temperature stress: Pavona

- Page 409 and 410:

7.15.2 Pavona cactus Forskål, 1775

- Page 411 and 412:

Life History Pavona cactus is a gon

- Page 413 and 414:

7.15.3 Pavona decussata Dana, 1846

- Page 415 and 416:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 417 and 418:

7.15.4 Pavona diffluens Lamarck, 18

- Page 419 and 420:

Threats Temperature stress: Pavona

- Page 421 and 422:

7.15.5 Pavona venosa (Ehrenberg, 18

- Page 423 and 424:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 425 and 426:

7.16 Genus Galaxea (Family Oculinid

- Page 427 and 428:

Abundance Galaxea astreata can be a

- Page 429 and 430:

7.17 Genus Pectinia (Family Pectini

- Page 431 and 432:

Acidification: Pectinia alcicornis

- Page 433 and 434:

7.18 Genus Acanthastrea (Family Mus

- Page 435 and 436:

Abundance Abundance of Acanthastrea

- Page 437 and 438:

7.18.2 Acanthastrea hemprichii Ehre

- Page 439 and 440:

Life History Reproductive character

- Page 441 and 442:

7.18.3 Acanthastrea ishigakiensis V

- Page 443 and 444:

Life History Reproductive character

- Page 445 and 446:

7.18.4 Acanthastrea regularis Veron

- Page 447 and 448:

Although specific larval descriptio

- Page 449 and 450:

7.19 Genus Barabattoia (Family Favi

- Page 451 and 452:

Threats Temperature stress: Unknown

- Page 453 and 454:

7.20 Genus Caulastrea 7.20.1 Caulas

- Page 455 and 456:

Threats Thermal stress: Unknown, bu

- Page 457 and 458:

7.21 Genus Cyphastrea 7.21.1 Cyphas

- Page 459 and 460:

Threats Thermal stress: The genus C

- Page 461 and 462:

7.21.2 Cyphastrea ocellina Dana, 18

- Page 463 and 464:

skeletal deposition is reduced unde

- Page 465 and 466:

7.22 Genus Euphyllia (Family Caryop

- Page 467 and 468:

Bruckner and Hill, 2009) and eviden

- Page 469 and 470:

7.22.2 Euphyllia paraancora Veron,

- Page 471 and 472:

Threats Thermal stress: Euphyllia p

- Page 473 and 474:

7.22.3 Euphyllia paradivisa Veron,

- Page 475 and 476:

Threats Thermal stress: Euphyllia s

- Page 477 and 478:

7.23 Genus Physogyra 7.23.1 Physogy

- Page 479 and 480:

al., 2007; Silverman et al., 2009).

- Page 481 and 482:

7.24 Genus Turbinaria (Family Dendr

- Page 483 and 484:

Threats Thermal stress: Bleaching i

- Page 485 and 486:

7.24.2 Turbinaria peltata (Esper, 1

- Page 487 and 488:

Acidification: A congener Turbinari

- Page 489 and 490:

7.24.3 Turbinaria reniformis Bernar

- Page 491 and 492:

Threats Thermal stress: Bleaching i

- Page 493 and 494:

7.24.4 Turbinaria stellulata Lamarc

- Page 495 and 496:

Life History The reproductive chara

- Page 497 and 498:

8. SYNTHESIS OF RISK ASSESSMENTS: T

- Page 499 and 500:

459

- Page 501 and 502:

Figure 8.2. Number of coral species

- Page 503 and 504:

Albright, R., Mason B., and Langdon

- Page 505 and 506:

Baggett, L. S., and Bright T. J. 19

- Page 507 and 508:

Bellwood, D., Hoey A., and Choat J.

- Page 509 and 510:

Brodie, J., Fabricius K., De'ath G.

- Page 511 and 512:

Carilli, J. E., Norris R. D., Black

- Page 513 and 514:

Coffroth, M. A. 1985. Mucus sheet f

- Page 515 and 516:

Cox, E. F. 1986. The effects of a s

- Page 517 and 518:

DESA, U. N. 2001. World Population

- Page 519 and 520:

Eakin, C. M., Feingold J. S., and G

- Page 521 and 522:

Feingold, J. S. 1996. Coral survivo

- Page 523 and 524:

Gardella, D. J., and Edmunds P. J.

- Page 525 and 526:

Glynn, P. W., Colley S. B., Ting J.

- Page 527 and 528:

Grover, R., Maguer J., Allemand D.,

- Page 529 and 530:

Hawkins, J. P., and Roberts C. M. 1

- Page 531 and 532:

Hubbard, D. K. 1992. Hurricane-indu

- Page 533 and 534:

Isdale, P. J., Stewart B. J., Tickl

- Page 535 and 536:

Kennedy, C. J., Gassman N. J., and

- Page 537 and 538:

Lafferty, K. D., Porter J. W., and

- Page 539 and 540:

Lindahl, U. 2003. Coral reef rehabi

- Page 541 and 542:

Maragos, J. E. 1993. Impact of coas

- Page 543 and 544:

McCormick, M. I. 2003. Consumption

- Page 545 and 546:

Morse, D. E., Morse A. N. C., Raimo

- Page 547 and 548:

Nugues, M., Delvoye L., and Bak R.

- Page 549 and 550:

Petit, J. R., Jouzel J., Raynaud D.

- Page 551 and 552:

Randall, C. J., and Szmant A. M. 20

- Page 553 and 554:

Riegl, B. 1996. Hermatypic coral fa

- Page 555 and 556:

Rotjan, R. 2007. The patterns, caus

- Page 557 and 558:

Siddall, M., Rohling E. J., Almogi-

- Page 559 and 560:

Streamer, M. 1980. Urea and arginin

- Page 561 and 562:

Titlyanov, E. A., and Latypov Y. Y.

- Page 563 and 564:

Venn, A. A., Quinn J., Jones R., an

- Page 565 and 566:

Ward, S. 1992. Evidence for broadca

- Page 567 and 568:

Williams, I.D., Walsh W., Schroeder

- Page 569 and 570:

Yost, D. M., Jones R. J., and Mitch

- Page 571 and 572:

Errata Erroneous references: IPCC.

- Page 573 and 574:

APPENDIX: Millepora boschmai (De We

- Page 575 and 576:

According to de Weerdt and Glynn (1

- Page 577 and 578:

The overall likelihood that Millepo

- Page 579 and 580:

Glynn, P. W., J. L. Mate, A. C. Bak

- Page 581:

Availability of NOAA Technical Memo