CHNN 22, Spring 2008 - School of Social Sciences

CHNN 22, Spring 2008 - School of Social Sciences

CHNN 22, Spring 2008 - School of Social Sciences

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

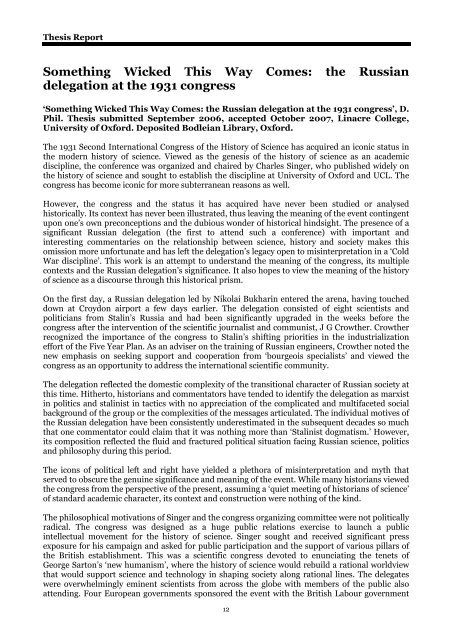

Thesis Report<br />

Something Wicked This Way Comes: the Russian<br />

delegation at the 1931 congress<br />

‘Something Wicked This Way Comes: the Russian delegation at the 1931 congress’, D.<br />

Phil. Thesis submitted September 2006, accepted October 2007, Linacre College,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Oxford. Deposited Bodleian Library, Oxford.<br />

The 1931 Second International Congress <strong>of</strong> the History <strong>of</strong> Science has acquired an iconic status in<br />

the modern history <strong>of</strong> science. Viewed as the genesis <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> science as an academic<br />

discipline, the conference was organized and chaired by Charles Singer, who published widely on<br />

the history <strong>of</strong> science and sought to establish the discipline at University <strong>of</strong> Oxford and UCL. The<br />

congress has become iconic for more subterranean reasons as well.<br />

However, the congress and the status it has acquired have never been studied or analysed<br />

historically. Its context has never been illustrated, thus leaving the meaning <strong>of</strong> the event contingent<br />

upon one’s own preconceptions and the dubious wonder <strong>of</strong> historical hindsight. The presence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

significant Russian delegation (the first to attend such a conference) with important and<br />

interesting commentaries on the relationship between science, history and society makes this<br />

omission more unfortunate and has left the delegation’s legacy open to misinterpretation in a ‘Cold<br />

War discipline’. This work is an attempt to understand the meaning <strong>of</strong> the congress, its multiple<br />

contexts and the Russian delegation’s significance. It also hopes to view the meaning <strong>of</strong> the history<br />

<strong>of</strong> science as a discourse through this historical prism.<br />

On the first day, a Russian delegation led by Nikolai Bukharin entered the arena, having touched<br />

down at Croydon airport a few days earlier. The delegation consisted <strong>of</strong> eight scientists and<br />

politicians from Stalin’s Russia and had been significantly upgraded in the weeks before the<br />

congress after the intervention <strong>of</strong> the scientific journalist and communist, J G Crowther. Crowther<br />

recognized the importance <strong>of</strong> the congress to Stalin’s shifting priorities in the industrialization<br />

effort <strong>of</strong> the Five Year Plan. As an adviser on the training <strong>of</strong> Russian engineers, Crowther noted the<br />

new emphasis on seeking support and cooperation from ‘bourgeois specialists’ and viewed the<br />

congress as an opportunity to address the international scientific community.<br />

The delegation reflected the domestic complexity <strong>of</strong> the transitional character <strong>of</strong> Russian society at<br />

this time. Hitherto, historians and commentators have tended to identify the delegation as marxist<br />

in politics and stalinist in tactics with no appreciation <strong>of</strong> the complicated and multifaceted social<br />

background <strong>of</strong> the group or the complexities <strong>of</strong> the messages articulated. The individual motives <strong>of</strong><br />

the Russian delegation have been consistently underestimated in the subsequent decades so much<br />

that one commentator could claim that it was nothing more than ‘Stalinist dogmatism.’ However,<br />

its composition reflected the fluid and fractured political situation facing Russian science, politics<br />

and philosophy during this period.<br />

The icons <strong>of</strong> political left and right have yielded a plethora <strong>of</strong> misinterpretation and myth that<br />

served to obscure the genuine significance and meaning <strong>of</strong> the event. While many historians viewed<br />

the congress from the perspective <strong>of</strong> the present, assuming a ‘quiet meeting <strong>of</strong> historians <strong>of</strong> science’<br />

<strong>of</strong> standard academic character, its context and construction were nothing <strong>of</strong> the kind.<br />

The philosophical motivations <strong>of</strong> Singer and the congress organizing committee were not politically<br />

radical. The congress was designed as a huge public relations exercise to launch a public<br />

intellectual movement for the history <strong>of</strong> science. Singer sought and received significant press<br />

exposure for his campaign and asked for public participation and the support <strong>of</strong> various pillars <strong>of</strong><br />

the British establishment. This was a scientific congress devoted to enunciating the tenets <strong>of</strong><br />

George Sarton’s ‘new humanism’, where the history <strong>of</strong> science would rebuild a rational worldview<br />

that would support science and technology in shaping society along rational lines. The delegates<br />

were overwhelmingly eminent scientists from across the globe with members <strong>of</strong> the public also<br />

attending. Four European governments sponsored the event with the British Labour government<br />

12