Grammatical Aspect in English and Kurdish - University of Sulaimani

Grammatical Aspect in English and Kurdish - University of Sulaimani

Grammatical Aspect in English and Kurdish - University of Sulaimani

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

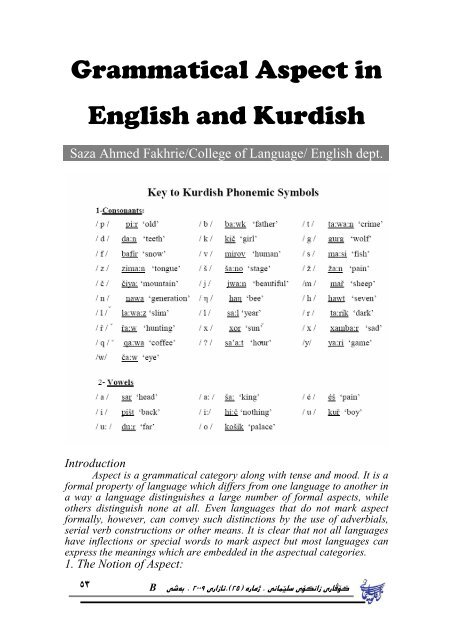

<strong>Grammatical</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

20<br />

<strong>English</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong><br />

Saza Ahmed Fakhrie/College <strong>of</strong> Language/ <strong>English</strong> dept.<br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> is a grammatical category along with tense <strong>and</strong> mood. It is a<br />

formal property <strong>of</strong> language which differs from one language to another <strong>in</strong><br />

a way a language dist<strong>in</strong>guishes a large number <strong>of</strong> formal aspects, while<br />

others dist<strong>in</strong>guish none at all. Even languages that do not mark aspect<br />

formally, however, can convey such dist<strong>in</strong>ctions by the use <strong>of</strong> adverbials,<br />

serial verb constructions or other means. It is clear that not all languages<br />

have <strong>in</strong>flections or special words to mark aspect but most languages can<br />

express the mean<strong>in</strong>gs which are embedded <strong>in</strong> the aspectual categories.<br />

1. The Notion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong>:<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

There are different views on aspect by different grammarians, among<br />

them, for example, is Hartmann <strong>and</strong> Stork’s view, who def<strong>in</strong>e aspect as “a<br />

grammatical category <strong>of</strong> the verb marked by prefixes, suffixes or <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

vowel changes <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g not so much its location <strong>in</strong> the (-tense) but the<br />

duration <strong>and</strong> type <strong>of</strong> the action expressed” (1972:20).<br />

Comrie (1976:3) states that “aspects are different ways <strong>of</strong> view<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the <strong>in</strong>ternal temporal consistuency <strong>of</strong> a situation”. While Smith (1976:61)<br />

has an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g view on aspect <strong>in</strong> his “camera- metaphor”, he mentions<br />

that “aspectual viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts function like the lens <strong>of</strong> a camera, mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

objects visible to the receiver. Situations are the objects on which<br />

viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts lenses are tra<strong>in</strong>ed”. Quirk et al. (1985:188) <strong>and</strong> Greenbaum<br />

<strong>and</strong> Quirk (1990:51) view aspect as “a grammatical category which<br />

reflects the way <strong>in</strong> which the verb is regarded or experienced with respect<br />

to time”. Crystal def<strong>in</strong>es aspect as “a category used <strong>in</strong> the grammatical<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> verbs (along with tense <strong>and</strong> mood) referr<strong>in</strong>g primarily to the<br />

way the grammar marks the duration or type <strong>of</strong> temporal activity denoted<br />

by the verb” (1991:27).<br />

While Gramely <strong>and</strong> Patzold (1992:146) expla<strong>in</strong> that aspect is not<br />

concerned with relat<strong>in</strong>g the time <strong>of</strong> the situation to any other time po<strong>in</strong>t,<br />

but rather with the <strong>in</strong>ternal temporal consistuency <strong>of</strong> the situation”.<br />

Richards et al (1992:22) identify aspect as that “grammatical<br />

category which deals with how the event described by a verb is viewed such<br />

as it is <strong>in</strong> progress, habitual, repeated, momentary, etc.” He also mentions<br />

that aspect may be <strong>in</strong>dicated by prefixes, suffixes or other categories <strong>of</strong> a<br />

verb.<br />

Trask (1993:21) describes aspect as “a grammatical category<br />

which relates to the <strong>in</strong>ternal temporal structure <strong>of</strong> a situation”.<br />

The above def<strong>in</strong>itions emphasize the relationship between aspect <strong>and</strong><br />

the duration <strong>of</strong> the action denoted by the verb. Among all these def<strong>in</strong>itions,<br />

the def<strong>in</strong>ition by Comrie is the most comprehensive. It draws a clear<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ction between ‘aspect’ <strong>and</strong> ‘tense’. One can realize the difference<br />

between situation-<strong>in</strong>ternal time (aspect) <strong>and</strong> situation-external time (tense).<br />

From these it can be concluded that aspect refers to the <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

temporal consistuency <strong>of</strong> an event or the manner <strong>in</strong> which the action <strong>of</strong> the<br />

verb is distributed through the time-space cont<strong>in</strong>uum. Tense, on the other<br />

h<strong>and</strong>, refers to the location <strong>of</strong> an event <strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>uum. However, only<br />

Hartmann <strong>and</strong> Stork (1972:20) pay attention to the form or the structural<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> ‘aspects’. They expla<strong>in</strong> that verbs change their forms by receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

prefixes, suffixes or <strong>in</strong>ternal vowel changes so as to denote the duration <strong>of</strong><br />

an action.<br />

2. The Notion <strong>of</strong> Time, Tense, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong>:<br />

It can be noticed that ‘aspect’ does not occur alone but it always<br />

occurs with ‘tense’. They relate the happen<strong>in</strong>g described by the verb to<br />

time <strong>in</strong> the past, present, or future (Leech <strong>and</strong> Svartvik 1994:65). <strong>Aspect</strong> is<br />

a difficult concept to grasp because it tends to conflate with the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

tense.<br />

The term ‘tense’ is related to the l<strong>in</strong>guistic expression <strong>of</strong> time<br />

21<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

elations which are realized by verb forms. While ‘time’ is an <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> language <strong>and</strong> it is common to all languages. It is viewed by<br />

many people, though not necessarily by all, as be<strong>in</strong>g divided <strong>in</strong>to past,<br />

present <strong>and</strong> future time. Tense systems are language-specific <strong>and</strong> vary from<br />

one language to another <strong>in</strong> a way that each language has different number<br />

<strong>of</strong> tenses to reflect temporal reference. (Dow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Locke 2002:353).<br />

The ma<strong>in</strong> difference between tense <strong>and</strong> aspect is that the former is<br />

concerned with relat<strong>in</strong>g a situation to a time-po<strong>in</strong>t, that is, situationexternal<br />

time. While the latter deals with the <strong>in</strong>ternal temporal<br />

consistuency <strong>of</strong> a situation, that is, situation- <strong>in</strong>ternal time (Comrie1976:5).<br />

It is worth mention<strong>in</strong>g that time refers to the possibility for relat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

situations to the time l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> discuss<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternal temporal contour <strong>of</strong> a<br />

situation; for <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong> discuss<strong>in</strong>g whether it is possible to be<br />

represented as a po<strong>in</strong>t or as a stretch on the time l<strong>in</strong>e. The <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

temporal contour <strong>of</strong> a situation refers to the conceptual basis for the notion<br />

<strong>of</strong> aspect which <strong>in</strong>dicates the grammaticalisation <strong>of</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

temporal constituency (Comrie1985:7). Thus, the difference between<br />

(1) a. John was s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

b. John is s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> tense which dist<strong>in</strong>guishes a location before the present<br />

moment <strong>and</strong> a location <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the present moment, while the difference<br />

between:<br />

(2) a. John was s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

b. John sang.<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> aspect because both sentences are <strong>in</strong> the past tense, while they<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate different aspects: (2a) is <strong>in</strong> the progressive aspect, it shows the<br />

non-completion <strong>of</strong> the act <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g; while (2b) is <strong>in</strong> the perfective aspect<br />

which determ<strong>in</strong>es the completion <strong>of</strong> the action.<br />

Tense <strong>and</strong> aspect are two <strong>in</strong>terrelated elements that can not be<br />

studied separately. Dahl (1985:24) regards tense as deictic categories<br />

which relate time po<strong>in</strong>ts to the moment <strong>of</strong> speech while aspect is as nondeictic<br />

category, that is, it relates time po<strong>in</strong>ts to the moment <strong>of</strong> event.<br />

3. Lexical vs. <strong>Grammatical</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong>:<br />

Celce-Murcia <strong>and</strong> Larsen-Freeman (1999:40) state that verbs have<br />

lexical as well as grammatical aspects. It is important to dist<strong>in</strong>guish<br />

between two types <strong>of</strong> aspects: lexical <strong>and</strong> grammatical. Lexical aspect<br />

refers to the <strong>in</strong>herent property <strong>of</strong> verbs which is not marked formally <strong>in</strong><br />

most languages. As far as this type <strong>of</strong> aspect is concerned, Vendler<br />

(1967:97) divides verbs <strong>in</strong>to four categories:’ activities’ (e.g. study),<br />

‘achievements’ (e.g. f<strong>in</strong>d), ‘accomplishments’ (e.g. write), <strong>and</strong> ‘states’ (e.g.<br />

have). Lexical or situation aspect is sometimes called Aktionsart which is<br />

regarded it as perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to the lexicon while aspect perta<strong>in</strong>s to the<br />

grammar (Dahl 1985:27).While grammatical aspect is related to a formal<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ction between the verb forms which are represented <strong>in</strong> the grammar<br />

<strong>of</strong> a language. The present study is devoted to grammatical aspect.<br />

4. <strong>Grammatical</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong>:<br />

22<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

<strong>Grammatical</strong> aspect is represented differently <strong>in</strong> different languages.<br />

For <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong> some languages, it is realized by prefixes, suffixes or other<br />

categories <strong>of</strong> the verb. There are different views concern<strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong><br />

the type <strong>of</strong> grammatical aspect <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong>. Some grammarians<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guished two ma<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> aspect, for example, Comrie classifies<br />

grammatical aspect <strong>in</strong>to two ma<strong>in</strong> types: perfective <strong>and</strong> imperfective; the<br />

former <strong>in</strong>dicates the situations <strong>of</strong> short duration while the latter <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

the situations <strong>of</strong> long duration (1976:16). While others draw a dist<strong>in</strong>ction<br />

between four types <strong>of</strong> grammatical aspect, these are: simple, perfect,<br />

progressive <strong>and</strong> perfect progressive aspect. For <strong>in</strong>stance, Celce-Murcia<br />

<strong>and</strong> Larsen-Freeman (1999:112-118) dist<strong>in</strong>guish four types <strong>of</strong> grammatical<br />

aspect <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong>:<br />

a. Simple aspect: it refers to events that are viewed as complete wholes.<br />

(3) a. Natalia helps her mother.<br />

b. Natalia helped her mother.<br />

b. Perfect aspect: the core mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> aspect is “prior” which<br />

is used <strong>in</strong> relation to some other po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> time, for example:<br />

(4) a. Natalia has helped her mother.<br />

b. Natalia had helped her mother when the guest arrived.<br />

c. Progressive aspect: the core mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> aspect is<br />

imperfective which represents an event <strong>in</strong> such a way that allows for it to<br />

be <strong>in</strong>complete or somehow limited.<br />

(5) a. Natalia is help<strong>in</strong>g her mother.<br />

b. Natalia was help<strong>in</strong>g her mother.<br />

d. Perfect progressive aspect: the term suggests that this aspect comb<strong>in</strong>es<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> “prior’ <strong>of</strong> the perfect with the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> “<strong>in</strong>completeness”<br />

<strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> the progressive aspect.<br />

(6) a. Natalia has been help<strong>in</strong>g her mother for two hours.<br />

b. Natalia had been help<strong>in</strong>g her mother that year.<br />

It is necessary to mention that each <strong>of</strong> these pairs is identical <strong>in</strong> aspect but<br />

different <strong>in</strong> tense.<br />

In <strong>English</strong>, two ma<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> aspects can be realized: marked <strong>and</strong><br />

unmarked. There are three grammatically marked aspects <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong> which<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate those aspects that are realized by <strong>in</strong>flectional morphemes that are<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive <strong>and</strong> perfect progressive aspects, for<br />

example: (7) a. He is play<strong>in</strong>g well<br />

b. He has played well.<br />

c. He has been play<strong>in</strong>g for two hours.<br />

In (7a), the aspect is marked by (be + -<strong>in</strong>g), while <strong>in</strong> (7b) it is<br />

marked by (have + PP) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> (7c) by (have + been + <strong>in</strong>g) which is a<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> the perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive aspects. So it can be considered<br />

as a marked aspect as well. It is worth mention<strong>in</strong>g that the third type <strong>of</strong><br />

marked aspect is not regarded as a marked aspect because it is a<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive aspects. Whereas the unmarked<br />

aspect refers to those types <strong>of</strong> aspect which are not realized by any markers<br />

which are determ<strong>in</strong>ed by simple aspect, for example:<br />

(8) a. He plays tennis well.<br />

23<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

Table 1.1<br />

b. He played tennis well.<br />

<strong>English</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> Systems<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> Mean<strong>in</strong>g Examples<br />

Simple<br />

Perfective<br />

past simple<br />

Imperfective<br />

present simple<br />

walked<br />

walk(s)<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past perfect<br />

had walked<br />

Imperfective<br />

present perfect have walked<br />

Progressive Imperfective past cont<strong>in</strong>uous was walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

present cont<strong>in</strong>uous is walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past perfect progressive had been walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

progressive Imperfective<br />

Present perfect progressive have been walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

5. <strong>Grammatical</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>:<br />

This section is devoted to the analysis <strong>and</strong> the identification <strong>of</strong> the<br />

grammatical aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>. Though this area <strong>of</strong> study has not been<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigated clearly because most traditional <strong>Kurdish</strong> grammarians assume<br />

that the verbal system is based on tense to which they have devoted most <strong>of</strong><br />

their <strong>in</strong>vestigations, therefore, they ignore the explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong><br />

aspect system. Another reason is that traditional <strong>Kurdish</strong> grammarians<br />

have adopted an Arabic grammatical model which is based on two tenses.<br />

Ahmad (2004:193) expla<strong>in</strong>s that <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>, grammatical aspect has<br />

its own properties: One <strong>of</strong> these is that <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong> the aspectual dist<strong>in</strong>ction<br />

perfective/ imperfective is morphologically marked by means <strong>of</strong> prefixes<br />

<strong>and</strong> suffixes. For <strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

(9) aw nan daxwat. ‘he eats’<br />

The prefix da- <strong>in</strong>dicates the non- completion <strong>of</strong> the act <strong>of</strong> ‘eat<strong>in</strong>g’.<br />

(10) aw nanakay xwar -Ø -d. ‘he ate’<br />

The symbol -Ø – which is not realized <strong>in</strong>dicates the completion <strong>of</strong> the act <strong>of</strong><br />

xward<strong>in</strong> ‘eat<strong>in</strong>g’.<br />

Fattah (1997:144) states that “the aspectual markers are purely<br />

<strong>in</strong>flectional. It marks a dist<strong>in</strong>ction between cont<strong>in</strong>uous (progressive or<br />

imperfective) <strong>and</strong> perfective.” He expla<strong>in</strong>s that the cont<strong>in</strong>uous aspect is<br />

signaled by d/a -, it is prefixed to present <strong>and</strong> past stems to yield present<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicative (cont<strong>in</strong>uous) <strong>and</strong> past imperfective (cont<strong>in</strong>uous) respectively:<br />

(11) da ro – m ‘I am go<strong>in</strong>g’ (present <strong>in</strong>dicative)<br />

asp. go + pr 1ps<br />

(12) da -m -kir-d ‘ I was do<strong>in</strong>g’ (past <strong>in</strong>dicative)<br />

asp-1ps -do -p<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Am<strong>in</strong> (1979:45) there are three types <strong>of</strong> aspects <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>:<br />

a. Perfective <strong>Aspect</strong>: It is not expressed by grammatical element, for<br />

<strong>in</strong>stance: (13) xward - m ‘I ate’<br />

The verb xward ‘eat+p’ is <strong>in</strong> the past <strong>and</strong> it has the perfective aspect<br />

b. Imperfective <strong>Aspect</strong>: it is marked by –da, <strong>and</strong> it is used with both past<br />

<strong>and</strong> present. (14) a. da - xo -m ‘ I eat’<br />

b. da - nust -m ‘ I was sleep<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

c. Perfect <strong>Aspect</strong>: it is used with past <strong>and</strong> present tenses:<br />

the past perfect aspect is marked by –bu:<br />

24<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

(15) ewa nu:st - bu - n ‘ you had slept’<br />

the present perfect is expressed by –ua:.<br />

(16) nan im xward - wua ‘ I have eaten’<br />

Ahmad (2008: 82-83) made use <strong>of</strong> Am<strong>in</strong>’s (2004:73) classification gives<br />

another type <strong>of</strong> aspect which is perfect cont<strong>in</strong>uous. It has the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

form:<br />

bu - past<br />

la + base + da + da + b–future + personal pronouns<br />

Ø - present<br />

(17) laøošt<strong>in</strong>+da+yn = laøoyšt<strong>in</strong>dayn ‘we are <strong>in</strong> the middle <strong>of</strong> walk<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

(18) laøošt<strong>in</strong> +da+bu+yn= laøošt<strong>in</strong>dabuyn ‘we were <strong>in</strong> the middle <strong>of</strong> walk<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

(19) laøošt<strong>in</strong> +da+dab+yn= laøošt<strong>in</strong>dadabyn ‘we will be <strong>in</strong> the middle <strong>of</strong> walk<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

Table 1.2 Am<strong>in</strong>’s classification <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong> aspectual system (2004:71)<br />

Tense <strong>Aspect</strong> Rules Examples<br />

past<br />

simple<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous<br />

perfect<br />

conditional<br />

past stem+ personal pronouns<br />

da+past stem+ personal pronouns<br />

past stem+bu:+ personal pronouns<br />

bi+ past stem+ personal<br />

pronouns+a:ya<br />

hat<strong>in</strong> - xwardman<br />

dahat<strong>in</strong> - damanxward<br />

hatibu<strong>in</strong> - xwardbu:man<br />

bihat<strong>in</strong>a:ya - bimanxwarda:ya<br />

present<br />

simple<br />

perfect<br />

da+ future stem”+ pers. prons.<br />

past stem+u:+ pers. prons.+ -a<br />

with <strong>in</strong>transitive verbs, -a appeared<br />

only with the third person s<strong>in</strong>gular.<br />

danu:si:n - danu:<strong>in</strong><br />

xwardumana - nu:stu<strong>in</strong><br />

Both Ahmad (2008:98) <strong>and</strong> Am<strong>in</strong> (2004:71) agree on that there are<br />

four types <strong>of</strong> aspect: simple, perfect, progressive <strong>and</strong> conditional. These<br />

aspects occur with the past <strong>and</strong> the present tenses. <strong>Kurdish</strong> does not have<br />

the perfect progressive aspect but <strong>in</strong>stead it has the conditional aspect.<br />

Table 1.3 Qadir’s classification <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong> aspectual system (2004:63)<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong><br />

marker<br />

da-<br />

-u- uw<br />

Mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a. it precedes the present stem <strong>and</strong> expresses the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> the action.<br />

b. it precedes the past stem <strong>and</strong> expresses the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

the action <strong>and</strong> it participates <strong>in</strong> the formation <strong>of</strong> past<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous.<br />

It occurs at the end <strong>of</strong> past simple <strong>and</strong> composes past<br />

perfect. The form <strong>of</strong> this aspect changes accord<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

type <strong>of</strong> the verb whether it is transitive or <strong>in</strong>transitive <strong>and</strong><br />

also accord<strong>in</strong>g to the morphemes <strong>of</strong> past.<br />

Examples<br />

a. darom ‘I go’<br />

b. dahatim ‘ I was com<strong>in</strong>g’.<br />

a. naxošaka mirduwa.<br />

‘the patient has died’<br />

b. èaka kulawa.<br />

‘ The tea has boiled’<br />

-a This morpheme expresses a permanent situation. zistan sarda.<br />

‘w<strong>in</strong>ter is cold’<br />

-awa/wa It occurs at the end <strong>of</strong> the stem, it has two roles: a. this<br />

suffix attaches to the past <strong>and</strong> present stems to <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

repetition. b. It also attaches to the present stem to show<br />

certa<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> the speech which is uttered by the speaker. It<br />

also <strong>in</strong>dicates the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the happen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> future<br />

time after speech.<br />

demawa.<br />

‘I will come back’<br />

25<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

Table 1.4 Ahmad’s classification <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong> aspectual system (2004:270):<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> Mean<strong>in</strong>g Examples<br />

perfective a. <strong>in</strong> the past, it is marked by t, d, i, a, u .<br />

b. <strong>in</strong> the non-past, it is restricted to subord<strong>in</strong>ate clauses with<br />

subjunctive marker b<strong>in</strong>u:st<br />

‘slept’<br />

bird ‘took’<br />

nu:si ‘wrote’<br />

hena ‘brought’<br />

èu: ‘went’<br />

imperfective It is marked by the comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> the imperfective marker da- daxom ‘I eat’<br />

Progressive<br />

26<br />

with both past <strong>and</strong> non-past stems.<br />

It is not restricted to one tense although it is clearer than <strong>in</strong> the<br />

present tense.<br />

damxward<br />

‘ I was eat<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

As far as the first type is concerned, he mentions that both past <strong>and</strong><br />

non-past perfective forms describe the situation as a s<strong>in</strong>gle- complete<br />

whole. They differ <strong>in</strong> that the former has past time reference <strong>and</strong> context<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent while the latter has future time reference <strong>and</strong> context<br />

dependent. Whereas the imperfective aspect has cont<strong>in</strong>uous, noncompletion<br />

<strong>and</strong> habitual <strong>in</strong>terpretation.<br />

He mentions that progressivity is classified under imperfectivity but<br />

they are two different notions because imperfectivity always expresses<br />

unlimited habiuality whereas progressivity may express limited habituality.<br />

The progressive aspect expla<strong>in</strong>s a situation which is <strong>in</strong> progress.<br />

From the above discussion, one can conclude that <strong>Kurdish</strong> has two ma<strong>in</strong><br />

aspect types: marked <strong>and</strong> unmarked. <strong>Kurdish</strong> marked aspects are those<br />

aspects which are realized by <strong>in</strong>flectional morphemes, it is marked by<br />

perfect (bu:) <strong>and</strong> progressive aspects (da-)<br />

(20) a. øošt i -bu: -n (‘ they had gone’)<br />

b. da – øoy št -n (‘we were go<strong>in</strong>g’)<br />

While the unmarked aspect refers to those types <strong>of</strong> aspect which are not<br />

realized by any markers .It is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by simple aspect.<br />

Here are the <strong>Kurdish</strong> aspects:<br />

1- Simple <strong>Aspect</strong>: it <strong>in</strong>dicates the completion or the non completion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

action. This aspect is unmarked for the past <strong>and</strong> present simple tenses. For<br />

<strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

(21) aw namaka –Ø- y nus i: ‘ he wrote a letter’ perfectiveness<br />

aw nama danu:set ‘ he writes a letter’ imperfectiveness<br />

The symbol / Ø/ <strong>in</strong>dicates the past simple aspect which determ<strong>in</strong>es the<br />

totality <strong>of</strong> the action, here the past verb does not carry any markers.<br />

2- Progressive <strong>Aspect</strong>: it can be realized by -da which <strong>in</strong>dicates the<br />

duration <strong>and</strong> the non-completion <strong>of</strong> the action. For <strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

(22) kuøaka namay da nu:si ka zang léyda perfectiveness<br />

‘he was writ<strong>in</strong>g a letter when the bell rang’<br />

3- Perfect <strong>Aspect</strong>: It can be realized by (bu:) ‘had done’ <strong>and</strong> (uwa)<br />

‘have+PP’, it is a situation which comb<strong>in</strong>es past with present time<br />

reference.<br />

(23) a. m<strong>in</strong> namakam nu:si –bu: ‘I had written the letter’<br />

perfectiveness<br />

b. m<strong>in</strong> namakam nu:siwa ‘I have written the letter’.<br />

imperfectiveness<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

Actually t <strong>and</strong> d are not aspect markers but they are past tense markers<br />

which are equivalent to the suffix past marker –ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong>. The<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g table summarizes the <strong>Kurdish</strong> aspect markers.<br />

Table 1.5 <strong>Kurdish</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> Systems<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g Examples<br />

Simple<br />

Perfective<br />

past simple<br />

xward Ø im<br />

Imperfective<br />

present simple da xom<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past perfect<br />

xward bu: m<br />

Imperfective<br />

present perfect xward uma<br />

Progressive Imperfective past cont<strong>in</strong>uous damxard<br />

present cont<strong>in</strong>uous daxom<br />

The above table shows the follow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

(1) If the prefix –da is not regarded as an aspect marker, the aspectual<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ctions are expressed by lexical elements, <strong>in</strong> this case it is a present<br />

tense morpheme.<br />

(2) If the prefix –da is regarded as an aspect marker, then all present verb<br />

stems are classified under progressive aspects. In this case the present<br />

tense morpheme is with<strong>in</strong> the verb stem itself.<br />

6. Po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> similarity <strong>and</strong> difference<br />

This section is devoted to the discussion <strong>and</strong> the identification <strong>of</strong><br />

po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> similarity <strong>and</strong> difference <strong>in</strong> the aspectual systems <strong>in</strong> the two<br />

languages.<br />

Similarities:<br />

1- In both languages both aspect <strong>and</strong> tense are related to the time<br />

references. Time is a semantic notion; aspect <strong>and</strong> tense are grammatical<br />

notions. They are grammaticalisations <strong>of</strong> time. Tense refers to the absolute<br />

location <strong>of</strong> an event or action <strong>in</strong> time while aspect refers to how an event or<br />

action is to be viewed with respect to time, rather than to its actual location<br />

<strong>in</strong> time.<br />

2- In both languages, the term aspect refers to the way <strong>of</strong> view<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal temporal constituency <strong>of</strong> a situation .It shows the completion or<br />

the non- completion <strong>of</strong> the action which is described by the verb form.<br />

3- In both languages, two ma<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> aspect can be dist<strong>in</strong>guished:<br />

marked or unmarked.<br />

4-In both languages, simple, perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive aspects are<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guished, for <strong>in</strong>stance: (24) a. John eats/ate the apple.<br />

b. John is/was eat<strong>in</strong>g the apple.<br />

c. John has/had eaten the apple.<br />

d. John has/had been eat<strong>in</strong>g the apple.<br />

(25) a. Jon sew daxwat.<br />

b. Jon sewi xwar-Ø-d.<br />

c. Jon sewi xwardi bu:.<br />

d. Jon sewi xwarduwa.<br />

e. Jon sewi daxward ka zangaka leida.<br />

3-<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

5- Each type <strong>of</strong> aspect <strong>in</strong> the two languages can be marked as perfective or<br />

imperfective which are realized by different tenses; as shown <strong>in</strong> the<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g tables:<br />

<strong>English</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> Systems<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> Mean<strong>in</strong>g Examples<br />

Simple<br />

Perfective<br />

past simple<br />

Imperfective<br />

present simple<br />

walked<br />

walk(s)<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past perfect<br />

had walked<br />

Imperfective<br />

present perfect have walked<br />

Progressive Imperfective past cont<strong>in</strong>uous was walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

present cont<strong>in</strong>uous is walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past<br />

had been walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

progressive Imperfective<br />

present<br />

have been walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Kurdish</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> Systems<br />

<strong>Aspect</strong> Mean<strong>in</strong>g Examples<br />

Simple<br />

Perfective<br />

past simple<br />

Imperfective<br />

present simple<br />

xward Ø im<br />

da xom<br />

Perfect<br />

Perfective<br />

past perfect<br />

xward bu: m<br />

Imperfective<br />

present perfect xward uma<br />

Progressive Imperfective past cont<strong>in</strong>uous damxard<br />

present cont<strong>in</strong>uous daxom<br />

Differences:<br />

1- In <strong>English</strong>, unlike <strong>Kurdish</strong>, another type <strong>of</strong> aspect is realized which is<br />

called perfect progressive aspect, for <strong>in</strong>stance:<br />

(25)John has been read<strong>in</strong>g for two hours.<br />

2- <strong>English</strong> has three grammatically marked aspects which are determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by: a- Perfect (have/had +P.P)<br />

b- Progressive (be + -<strong>in</strong>g)<br />

c- Perfect Progressive (have/had + been + - <strong>in</strong>g) aspects.<br />

(26) a. John has read the novel.<br />

b. John is read<strong>in</strong>g the novel.<br />

c. John has been read<strong>in</strong>g the novel.<br />

While the unmarked aspect is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by simple aspect:<br />

(27) a. John reads the novel.<br />

b. John read the novel.<br />

<strong>Kurdish</strong> has two grammatically marked aspects: perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive.<br />

(28) a. dara mozi xward-bu. ‘ dara had eaten a banana’<br />

b. dara mozi daxward. ‘ dara is eat<strong>in</strong>g a banana’<br />

Whereas <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>, the unmarked aspect is realized by simple aspect<br />

(29) dara mozi xward ‘ dara ate an apple’<br />

3- In <strong>Kurdish</strong>, there are two types <strong>of</strong> the prefix –da which have different<br />

grammatical functions: <strong>in</strong> simple aspect, if – da precedes the verb stem, it<br />

is not regarded as an aspect marker but it is a present tense morpheme but<br />

if an adverb <strong>of</strong> time is <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong>to the sentence, <strong>in</strong> that case the aspect is<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated by a lexical element which is a lexical aspect rather than<br />

3.<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

grammatical aspect. This expla<strong>in</strong>s why <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong> simple aspect is<br />

grammatically unmarked.<br />

(30) a. darom<br />

b. m<strong>in</strong> ésta darom.<br />

While <strong>in</strong> progressive aspect, the prefix –da which precedes the verb stem is<br />

considered an aspect marker, <strong>in</strong> that case all present verb stems are<br />

classified under progressive aspect .Hence the present tense morpheme is<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the verb stem itself.<br />

7- Conclusions<br />

<br />

<br />

1. In both languages the terms time, tense <strong>and</strong> aspect are closely<br />

<strong>in</strong>terrelated. Time is a semantic notion; aspect <strong>and</strong> tense are grammatical<br />

notions. They are grammaticalisations <strong>of</strong> time. Tense refers to the time <strong>of</strong> a<br />

situation while aspect <strong>in</strong>dicates the duration <strong>and</strong> the non duration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

action.<br />

2- In both languages, two ma<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> aspects can be realized: marked<br />

<strong>and</strong> unmarked. The former refers to those aspects which are realized by<br />

grammatical morphemes while the latter are those types <strong>of</strong> aspects which<br />

are not realized by any grammatical markers.<br />

3. In <strong>English</strong>, there are three grammatically marked aspects which are<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by perfect, progressive <strong>and</strong> perfect progressive aspects while<br />

there are two grammatically marked aspects <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>. They are<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by perfect <strong>and</strong> progressive aspects.<br />

4. <strong>English</strong> has four types <strong>of</strong> aspects: simple, perfect, progressive <strong>and</strong><br />

perfect progressive while <strong>Kurdish</strong> has only simple, perfect ad progressive<br />

aspects.<br />

5. In both languages the grammatical aspect markers are <strong>in</strong>dicated by<br />

grammatical morphemes.<br />

6. In <strong>Kurdish</strong>, two types <strong>of</strong> the prefix –da can be realized:<br />

-da which precedes the present verb stems which is a present tense<br />

morpheme <strong>and</strong> it is not regarded as an aspect marker ,<strong>in</strong> that case aspect is<br />

realized by lexical elements such as time adverbs.<br />

-da which precedes the verb stem is an aspect marker which determ<strong>in</strong>es<br />

the duration or the non-completion <strong>of</strong> the action , <strong>in</strong> this case ,all present<br />

verb stems are classified under progressive aspect <strong>and</strong> the present verb<br />

morpheme is with<strong>in</strong> the verb stem itself.<br />

7- In both languages, the aspect types can be conceptualized as perfective<br />

or imperfective depend<strong>in</strong>g on the completion or the non – completion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

action.<br />

3/<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

References<br />

1- Ahmed, M. F. (2004). The Tense <strong>and</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> System <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>.<br />

Unpublished Ph D. dissertation, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> London.<br />

2- Ahmad, Zh. O. (2008) Tense- <strong>Aspect</strong> System <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>.<br />

Unpublished MA thesis, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sulaimany.<br />

3- Am<strong>in</strong>, W.O (2004) è<strong>and</strong> asoyaki tri zimanawani: A New Horizon <strong>of</strong><br />

L<strong>in</strong>guistics. Arbil: Aras Press.<br />

4--------------------- (1979) <strong>Aspect</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the Verbal Construction <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>.<br />

Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> London.<br />

5- Celce-Murcia, M. <strong>and</strong> D. Larsen – Freeman (1999) The Grammar Book:<br />

An ESL/ EFL teachers course. (2 nd ed). Stamford, CT: He<strong>in</strong>le <strong>and</strong> He<strong>in</strong>le.<br />

6- Comrie, B. (1985). Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

7- Comrie, B. (1976) <strong>Aspect</strong>. Cambridge: Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

8- Crystal, D.(1991) A Dictionary <strong>of</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>and</strong> Phonetics. Oxford:<br />

Basil Blackwell.<br />

9- Dahl,O. (1985) Tense <strong>and</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> Systems. Oxford: Blackwell.<br />

10-Dow<strong>in</strong>g, Angela <strong>and</strong> Philip Locke (2002)A <strong>University</strong> Course <strong>in</strong> <strong>English</strong><br />

Grammar. London: Routledge.<br />

11- Fattah, M. M. (1997). A Generative Grammar <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kurdish</strong>.<br />

Unpublished Ph D. dissertation, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Amsterdam.<br />

12- Gramely, S. <strong>and</strong> K. M. Pätzold, (1992)A Survey <strong>of</strong> Modern <strong>English</strong>.<br />

London: Routledge.<br />

13-Greenbaum, S. <strong>and</strong> R.Quirk (1990) A Student's Grammar <strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong><br />

Language. London: Longman.<br />

14-Hartmann, R. R.; F.C.Stork, (1972) A Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Language <strong>and</strong><br />

L<strong>in</strong>guistics. London: Applied Science publisher.<br />

15- Leech, G. <strong>and</strong> J. Svartvik, (1994) A Communicative Grammar <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>English</strong>, (2nd edition), London: Longman.<br />

16- Qadir, A. O. (2003) barawirdeki morfo-s<strong>in</strong>taksy la zmani Kurdy w<br />

Farsida: A morpho-syntactic comparison <strong>in</strong> Kurdush <strong>and</strong> Persian,<br />

unpublished PhD. dissertation. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sulaimany.<br />

17- Quirk, R. S.Greenbaum, G. Leech, <strong>and</strong> J. Svartvik, (1985). A<br />

Comprehensive Grammar <strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong> Language. London: Longman.<br />

18- Richards, J. C.; J. Platt; H. Platt (1992) Longman Dictionary <strong>of</strong><br />

Language Teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Applied L<strong>in</strong>guistics. Engl<strong>and</strong>: Longman Group<br />

UK Limited<br />

19- Smith, C. (1997) The Parameter <strong>of</strong> <strong>Aspect</strong> (2 nd edn.) Dordrecht:<br />

Kluwer.<br />

20- Trask, R. L. (1993) A Dictionary <strong>of</strong> <strong>Grammatical</strong> Terms <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics.<br />

London: Routledge.21- Vendler, Z. (1976) L<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong> Philosophy.<br />

Ithaca, NY: Cornell <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

30<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}

ÏÉÐÂÌð¹Ùâ̹ÒÐL_ÊO<br />

g?chµÑÁ@½jâËögâÌPkÐÔ<br />

?dËcgʵÉÒj̺ïÂÌÔÑÁ@½iй<br />

<br />

ÑÁ@]]½iÉÉcgÐ]]ÅÐ]]¹Ïg?ch]]µÑÁ@]]½jâËögâÌP]]kÐÔÍËg@µcgÉ?gÐ]]GѵÐ]]ËÏÉÐÂÌð¹Ùâ̹Ð]]k@GÀÐ]]Ô<br />

Tense ?c°@]KÉ TimeN@]µâ¼Ð]}Ð¹Ò d]ÁÏÊËÐOÉMâÌP]kÐÔѽÐ]w?d]Ë@ÌKÐ]µ?d]ËcgʵÊ]Òj̺ïÂÌÔ<br />

+ÉÉögÐKÉ?h_<br />

ÉÏÉÐ]ÁÉÊGÏg@GÉÉc)ѽ?ÉÏcgÐ]G)ÄchâÌPL]kÏcÒÐ]ïÁ?ÉÉögÐ]¹&ÑÁ@]µÏgâÊSÉÑÁ@]½jâËögâÌP]kÐÔÄ@]o@O<br />

Ð]GÑ]âËögÐ]¹h]K?Éc)ÏÉÐ]KÏÉ?hÁÉÉög?dËcgʵÉÒj̺ïÂÌÔÑÁ@½iÉÉcgÐÅÒg?chµÒÐLkÉgcй%ÄÉÊGÉ?ÉÐK<br />

ÑÁÐ]ËÚÉÏÉ?hµcgÉ?gÐ]GÑÁ@]½jâËögâÌP]kÐÔÑÁ@]µÏgâÊSÐ]µÐÁ@½iÉÉcgÐ]ÅÒg?ch]µÒÐL]kÉgcÑÁchµcgÉ?g<br />

+ÏÉÊK@]]ÅÑ]]Ë@]]KâʵÄ@µÏÉ@]]wgÐkÑLl]]̹ÉÀ@Ð]]ÔÐ]]GÐ]]µÏÉÐÂÌð¹âÊâ̹+ÏÉ?gdÁ@pÌÁÄ@ÌËi?É@ÌSÉÄÉÊxâ̹<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

ÐsÛ?<br />

»¦®º¹ÐËÊX¹?й@?<br />

ÐËch¹?ÉÐËj̺Ú?Lªº¹?<br />

<br />

»¾p]KÉ+Ð]Ëch¹?ÉÐ]Ëj̺Ú?L]ªº¹?Ñ]»]¦®º¹Ð]ËÊX¹?Ð]¹@?Ñ]Ð]Ág@²½Ðk?gcÈfÅ<br />

Ð]¹@?»ÌºÉZÌwÊKÉ+%tense&ýj¹?É%time&M±Ê¹@G@ÆL±Û¥É%aspect&й@?ÀÊÆ®½<br />

ÉÐËg?h¾L]kÚ?ɨÉhp]¹?Ñ]º¥Ú?c@]ÆÁʵQ]ÌWÃ]½@]Æ¥?ÊÁ?É%grammatical aspect& ÐËÊX¹?<br />

I]̵hK³]Ëh}Ã]¥¿]OÃ]½É+Ð]Ëch¹?ÉÐ]Ëj̺Ú?L]ªº¹?Ñ»¦®¹?I̵hKѼ@¾LµÚ?Ég?hL¹?<br />

ÐËÊX¹?й@?¨?ÊÁ?Ñ°ÛL_Ú?ÉÇG@pL¹?ÇSÉ?g@Æw?@ÆLÁg@²½ÉÐËÊX¹?й@?¨?ÊÁ?É»¦®¹?<br />

+§S?h?Égc@t@GоÔ@±§½N@S@LÂLkÚ?@GÐk?gd¹?ÑÆLÂKÉ+Kgʵf?Lªº¹?Ñ »¦®º¹<br />

31<br />

BÑoÐG+/--6Òg?i@Ô+%/2&Ïg@½e+ÑÁ@¾â̺kÒÙÁ?iÒg@¡Ù}