S ongquan D eng / Shutterstock .com - University of Nevada School ...

S ongquan D eng / Shutterstock .com - University of Nevada School ...

S ongquan D eng / Shutterstock .com - University of Nevada School ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Health Risks & Behaviors<br />

Gambling & Other Process Addictions<br />

Process addictions such as pathological gambling,<br />

Internet addiction, food addiction, etc., show<br />

neurobiological, stimulus-reward patterns similar<br />

to substance addictions. In addition, process<br />

addictions show similarities in the progression<br />

from social use to abuse and dependency. And<br />

just like substance dependence, process addictions<br />

may result in <strong>com</strong>pulsive behaviors and craving,<br />

continuing the behavior in spite <strong>of</strong> adverse<br />

consequences, and loss <strong>of</strong> control over the behavior.<br />

Scientists now acknowledge the similarities<br />

between substance dependence and pathological<br />

gambling.<br />

The National Council on Problem Gambling<br />

(NCPG, 2012) estimated that 85% <strong>of</strong> all U.S.<br />

adults have gambled at least once in their lives<br />

and 60% have gambled in the past year. Of these,<br />

approximately 1%, or 2 million adults, met the<br />

diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling, and<br />

2-3%, or 4-6 million, were problem gamblers<br />

(NCPG, 2012). In a nationally representative study<br />

<strong>of</strong> U.S. households between 2001 and 2003, 78.4%<br />

<strong>of</strong> participants reported gambling at least once in<br />

their lifetime; the prevalence estimate for lifetime<br />

problem gambling was 2.3%; and the estimate<br />

for lifetime pathological gambling was 0.6%<br />

(Kessler et al, 2008). Age <strong>of</strong> onset for those who<br />

eventually became problem gamblers (median age<br />

= 21) was later than for non-problem gamblers<br />

(median age = 18; p. 1354). Rank-order popularity<br />

<strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> gambling did not differ across<br />

pathological and non-problem gamblers. However,<br />

the percentage <strong>of</strong> pathological gamblers who chose<br />

specific types <strong>of</strong> gambling was higher than for all<br />

gamblers (see Figure HR12).<br />

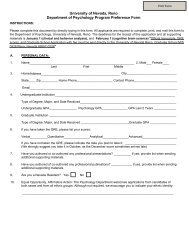

Fig. HR12: Popularity <strong>of</strong> Gaming by<br />

Gambler Type<br />

Speculating on High Risk Investments<br />

Internet Gambling<br />

Sports Betting: Bookie/Parlay Card<br />

Office Sports Pools<br />

Gambling at a Casino<br />

Slot Machines or Bingo<br />

Numbers/Lotto<br />

All Gamblers<br />

8.4%<br />

26.9%<br />

1.0%<br />

7.5%<br />

5.8%<br />

45.3%<br />

44.3%<br />

85.1%<br />

44.7%<br />

78.5%<br />

48.9%<br />

77.3%<br />

62.2%<br />

86.5%<br />

Pathological Gamblers<br />

In addition, the odds <strong>of</strong> developing a pathological<br />

gambling disorder increased by type <strong>of</strong> gaming.<br />

Games requiring mental skill (card games such<br />

as poker, bridge, etc.) posed the highest risk <strong>of</strong><br />

association with pathological gambling. Further,<br />

Kessler et al.’s (2008) study supported previous<br />

research showing <strong>com</strong>orbidity between pathological<br />

gambling and bipolar disorder, substance use<br />

disorders, and panic disorder. These mental health<br />

disorders preceded the onset <strong>of</strong> pathological<br />

gambling.<br />

Gambling studies <strong>of</strong> adults 50 and older also<br />

indicated an increase in prevalence <strong>of</strong> lifetime<br />

gambling, from 35% in 1975 to 80% in 1998<br />

(National Opinion Research Center, 1999, in Tse,<br />

Hong, Wang & Cunningham-Williams, 2012,<br />

p. 639). Prevalence rates <strong>of</strong> lifetime pathological<br />

gambling varied widely based on the populations<br />

selected (e.g., older adults in nursing facilities<br />

versus those in casinos or bingo establishments),<br />

the gambling-assessment instruments used, and<br />

the types <strong>of</strong> gambling assessed (Tse et al, 2012).<br />

However, all studies consistently reported lower<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> problem/pathological gambling<br />

in older adults than in younger adults, and that<br />

gambling disorders were more prevalent among<br />

older males than older females (Tse et al, 2012, p.<br />

645).<br />

Stitt, Giacopassi and Nichols’ (2003) study <strong>of</strong> older<br />

adults and gambling in casinos suggests that casino<br />

gambling might not be a major threat to older adults.<br />

In a survey <strong>of</strong> 2,768 individuals, these researchers<br />

found that adults 63 and older were more likely<br />

to visit casinos than were adults 62 and younger;<br />

however, there were no age differences in the time<br />

spent in the casinos. A greater percentage <strong>of</strong> older<br />

females (43.7%) indicated they gambled than older<br />

males (33.3%). Older adults tended to spend less<br />

money gambling than younger adults, and fewer<br />

older adults reported losing more money than they<br />

could afford.<br />

100<br />

(Kessler, Hwang, LaBrie, Petukhova, Sampson, Winters, &<br />

Shaffer, 2008)