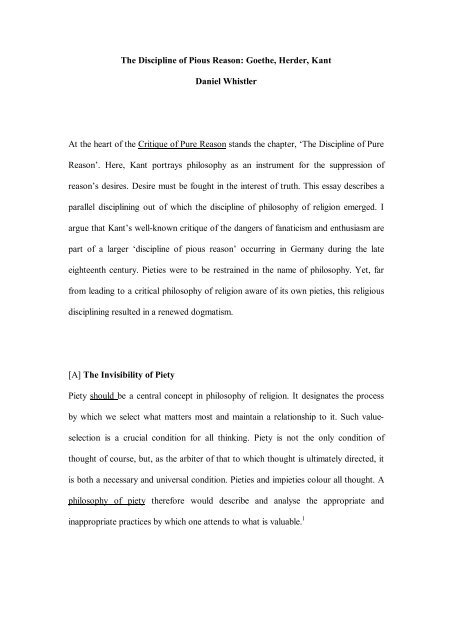

The Discipline of Pious Reason: Goethe, Herder, Kant Daniel ...

The Discipline of Pious Reason: Goethe, Herder, Kant Daniel ...

The Discipline of Pious Reason: Goethe, Herder, Kant Daniel ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Discipline</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pious</strong> <strong>Reason</strong>: <strong>Goethe</strong>, <strong>Herder</strong>, <strong>Kant</strong><br />

<strong>Daniel</strong> Whistler<br />

At the heart <strong>of</strong> the Critique <strong>of</strong> Pure <strong>Reason</strong> stands the chapter, ‘<strong>The</strong> <strong>Discipline</strong> <strong>of</strong> Pure<br />

<strong>Reason</strong>’. Here, <strong>Kant</strong> portrays philosophy as an instrument for the suppression <strong>of</strong><br />

reason’s desires. Desire must be fought in the interest <strong>of</strong> truth. This essay describes a<br />

parallel disciplining out <strong>of</strong> which the discipline <strong>of</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion emerged. I<br />

argue that <strong>Kant</strong>’s well-known critique <strong>of</strong> the dangers <strong>of</strong> fanaticism and enthusiasm are<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a larger ‘discipline <strong>of</strong> pious reason’ occurring in Germany during the late<br />

eighteenth century. Pieties were to be restrained in the name <strong>of</strong> philosophy. Yet, far<br />

from leading to a critical philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion aware <strong>of</strong> its own pieties, this religious<br />

disciplining resulted in a renewed dogmatism.<br />

[A] <strong>The</strong> Invisibility <strong>of</strong> Piety<br />

Piety should be a central concept in philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion. It designates the process<br />

by which we select what matters most and maintain a relationship to it. Such valueselection<br />

is a crucial condition for all thinking. Piety is not the only condition <strong>of</strong><br />

thought <strong>of</strong> course, but, as the arbiter <strong>of</strong> that to which thought is ultimately directed, it<br />

is both a necessary and universal condition. Pieties and impieties colour all thought. A<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> piety therefore would describe and analyse the appropriate and<br />

inappropriate practices by which one attends to what is valuable. 1

Nevertheless, the silence <strong>of</strong> contemporary philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion on piety is quite<br />

deafening. Piety seems to elude the critical gaze. It is for such reasons that I will<br />

speak at the end <strong>of</strong> the essay <strong>of</strong> the anti-transcendental nature <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion; it has suppressed the conditions which made it possible. <strong>The</strong><br />

obvious question is therefore: What reasons can be given for philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion’s<br />

suppression <strong>of</strong> the conditions <strong>of</strong> its own possibility? This question structures the<br />

present essay. I ask how and why piety ‘became invisible’ and I do so by describing<br />

three ‘scenes’ from the history <strong>of</strong> ideas which take place at the intersection between<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion and moral philosophy: two early poems by <strong>Goethe</strong> (Ganymed<br />

and Prometheus) a short essay by <strong>Herder</strong> (Liebe und Selbstheit) and the closing<br />

sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kant</strong>’s Metaphysik der Sitten. All three dramatise the effacement <strong>of</strong> piety<br />

from philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion.<br />

In these ‘scenes’, <strong>Goethe</strong>, <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong> confront the dominant pieties <strong>of</strong> their day<br />

and stutteringly articulate alternative, <strong>of</strong>ten improper models for relating to what<br />

matters most (i.e. ‘God’). All three are uneasy over how piety is usually conceived, so<br />

try to conceive it differently. <strong>The</strong> piety being challenged was essentially neoplatonic<br />

and itself had only recently come to dominance as a by-product <strong>of</strong> the Platorenaissance<br />

in post-1750 Germany. This neoplatonic piety was tethered to the figure<br />

<strong>of</strong> the One and postulated a future fusion with the divine. <strong>The</strong> impiety <strong>of</strong> <strong>Goethe</strong>,<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong> focused, on the contrary, on the multiplicity <strong>of</strong> existence. This<br />

concern for multiplicity was <strong>of</strong>ten mediated (oddly enough) through Spinozist ethics.<br />

Neo-Spinozistic impiety designated the manner in which the individual relates to God<br />

as individual, released from the bonds <strong>of</strong> fusion, mysticism and apotheosis. Impieties<br />

<strong>of</strong> the multiple were pitted against pieties <strong>of</strong> the One.

More concretely, <strong>Goethe</strong>, <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong> set limits to and posited restraints against<br />

the dangers posed by a neoplatonic thinking which exhibited too great a familiarity<br />

with the divine. <strong>The</strong> latter was too interested, and with such interest came the danger<br />

<strong>of</strong> being overwhelmed and ultimately engulfed by the deity. Impiety therefore took<br />

the form <strong>of</strong> an inhibition <strong>of</strong> reason, locking down its capabilities in favour <strong>of</strong> what<br />

<strong>Kant</strong> termed a pudor pietatis. Out <strong>of</strong> this restraint, philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion (or, at least,<br />

one form <strong>of</strong> it) was born. In late eighteenth century Germany, philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion<br />

was engendered as a disinterested enterprise: to philosophise one must keep one’s<br />

distance from the divine. While the philosopher is to be forever tempted by the divine,<br />

she must vigilantly thwart and frustrate such a desire. As such, she must struggle<br />

towards an improper indifference to the divine.<br />

[A] <strong>Goethe</strong>: <strong>Pious</strong> Desires and Impious Revolts<br />

I begin, then, with two <strong>of</strong> <strong>Goethe</strong>’s poems—Ganymed and Prometheus. Both written<br />

in the early 1770s, they are testament to an emergent dialectic between an attitude <strong>of</strong><br />

succumbing to the divine and one <strong>of</strong> resisting it. 2 <strong>The</strong> final stanza <strong>of</strong> Ganymed runs as<br />

follows,<br />

Hinauf! Hinauf strebt’s.<br />

Es schweben die Wolken<br />

Abwärts, die Wolken<br />

Neigen sich der sehnenden Liebe.<br />

Mir! Mir!

In euerm Schoose<br />

Aufwärts!<br />

Umfangend umfangen<br />

Aufwarts an deinen Busen,<br />

Allliebender Vater! (1919, I/2:79-80)<br />

Upwards, drawn upwards,<br />

<strong>The</strong> clouds float down,<br />

<strong>The</strong> clouds descend<br />

To my love and my longing,<br />

To me! To me!<br />

Upwards, carried in their womb,<br />

Embraced and embracing!<br />

Borne al<strong>of</strong>t to your heart,<br />

Oh father, lover <strong>of</strong> all! (2005, p. 9)<br />

Ganymed treats romantic love, love <strong>of</strong> nature and love <strong>of</strong> god. It is this last,<br />

theological level which is my present concern. Ganymede climaxes in divine love; the<br />

consummation <strong>of</strong> his existence (both its terminus and perfection) is to be absorbed<br />

back into the womb <strong>of</strong> the divine. Human desire is fulfilled in theosis. <strong>The</strong> telos <strong>of</strong><br />

individual life occurs at the moment when the god descends, humanity ascends and<br />

the two are fused together, so that all finite individuality is dissolved. Although<br />

<strong>Goethe</strong> adds romantic and pantheistic overtones, his model is therefore a traditional<br />

Christian one: blessedness is achieved by means <strong>of</strong> a dialectic <strong>of</strong> descent and ascent.<br />

God descends to Ganymede to embrace him (emptying Himself in the process), and in

that embrace human and God ascend back in glorification. <strong>The</strong>re is no moment <strong>of</strong><br />

equality.<br />

<strong>The</strong> underlying model <strong>of</strong> Ganymed can be further determined as neoplatonic; indeed,<br />

the poem bears the imprint <strong>of</strong> the neoplatonic renaissance which was spreading<br />

through Germany at this period. 3<br />

For both the <strong>Goethe</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ganymed and the<br />

neoplatonists <strong>of</strong> his day, proper human desire is desire for a return to unity with the<br />

One. It is no accident that later in his life ‘<strong>Goethe</strong> discovered in the thought <strong>of</strong><br />

Plotinus something very congenial to his own’ (Beierwaltes, 1972, p. 93). 4<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Goethe</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ganymed could have agreed as early as 1774 with Plotinus’ comments<br />

concerning ‘the love innate in our souls’:<br />

Every soul is an Aphrodite… As long as the soul stays true to itself, it loves the<br />

divinity and desires to be at one with it, as a daughter loves with a noble love a<br />

noble father… Only in the world beyond does the real object <strong>of</strong> our love exist, the<br />

only one with which we can unite ourselves. (1964, VI.9.9)<br />

It is important to note that <strong>Goethe</strong> conceives the One not as transcendent to the world<br />

<strong>of</strong> sense, but (in part, at least) identical with it; yet, despite this shift in emphasis, the<br />

desire to be borne ‘upwards… embraced and embracing’ remains the same. <strong>The</strong> claim<br />

that ‘love unites beings’ (<strong>Herder</strong>, 1994, 4:407; 1993, p. 111) is, as we shall see, the<br />

premise <strong>of</strong> all neoplatonic piety <strong>of</strong> the late eighteenth century.<br />

<strong>The</strong> naturalness <strong>of</strong> this desire to return to the One is a central component <strong>of</strong> the<br />

imitatio Dei and the imago Dei, both <strong>of</strong> which <strong>Goethe</strong> here flirts with. Desire for

union is the natural inclination <strong>of</strong> humanity: humanity lives to ultimately become like<br />

God. This natural inclination is also the effect <strong>of</strong> the divinity implanted in humanity<br />

from the beginning. 5 In line with this implant, the individual strives to revert back to<br />

her source and, in so doing, rise above the finite realm. For all these doctrines, fusion<br />

is the appropriate goal <strong>of</strong> human striving. <strong>The</strong> proper—or pious—relation to God is<br />

one that puts an end to all relations by merging God and humanity together into the<br />

One. In consequence, it also puts an end to all piety and to finitude altogether. This is<br />

a self-destructive form <strong>of</strong> piety. 6<br />

Contemporaneous with Ganymed, <strong>Goethe</strong> wrote the poem Prometheus. Its second<br />

stanza reads,<br />

Ich kenne nichts Ärmeres<br />

Unter der Sonn’, als euch, Götter!<br />

Ihr nähret kümmerlich<br />

Von Opfersteuern<br />

Und Gebetshauch<br />

Eure Majestät<br />

Und darbtet, wären<br />

Nicht Kinder und Bettler<br />

H<strong>of</strong>fnungsvolle Toren.<br />

I know <strong>of</strong> no poorer thing<br />

Under the sun, than you gods!<br />

Wretchedly you feed

Your own majesty<br />

On sacrificial <strong>of</strong>ferings<br />

And the breath <strong>of</strong> prayers,<br />

And you would starve<br />

If children and beggars<br />

Were not fools full <strong>of</strong> hope.<br />

<strong>The</strong> narrator (Prometheus) goes on to narrate his own childish and ‘deluded’ faith in<br />

divine mercy, before continuing later in the poem,<br />

Ich dich ehren? W<strong>of</strong>ür?<br />

Hast du die Schmerzen gelindert<br />

Je des Beladenen?<br />

Hast du die Thränen gestillet<br />

Je des Geängsteten?<br />

… Hier sitz’ ich, forme Menschen<br />

Nach meinem Bilde,<br />

Ein Geschlecht, das mir gleich sei,<br />

Zu leiden, zu weinen,<br />

Zu genießen und zu freuen sich,<br />

Und dein nicht zu achten,<br />

Wie ich! (1919, I/2:76-8)<br />

I should respect you? For what?

Have you ever soothed<br />

<strong>The</strong> pain that burdened me?<br />

Have you ever dried<br />

My terrified tears?<br />

… Here I sit, making men<br />

In my own image,<br />

A race that shall be like me,<br />

A race that shall suffer and weep<br />

And know joy and delight too,<br />

And heed you no more<br />

Than I do! (2005, pp. 11-13)<br />

While it might be slightly hyperbolic to claim with Boyle that ‘neither Nietzsche or<br />

Feuerbach will add anything <strong>of</strong> emotional or intellectual significance to this outburst<br />

<strong>of</strong> an Antichrist’ (1991, p. 164), it is certainly correct to assert that the metaphysics,<br />

theology and ethics underlying Ganymed are here rejected in their entirety.<br />

Prometheus forms a race <strong>of</strong> men in his own image—the image <strong>of</strong> revolt and<br />

autonomy. Humans are hardwired to impiety. Desire for God is transformed into<br />

desire against or despite the gods. This is what is natural to humanity: to remain selfsufficient,<br />

liberated from divine aid and divine demands. <strong>The</strong> human individual is<br />

born free <strong>of</strong> the gods—and this is something to be celebrated, since the gods are<br />

despicable creatures, feeding on sacrifice, prayer and hope only to give slavery in<br />

return. We are far away from the pious desires <strong>of</strong> Ganymed. <strong>The</strong> allure <strong>of</strong> the<br />

theological has been neutralised. If ‘philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion has no higher task than to

question dominant pieties’ (Goodchild, 2002, p. 3), then Prometheus is a crucial text<br />

in the genesis <strong>of</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion.<br />

If Ganymed is the <strong>of</strong>fspring <strong>of</strong> the neoplatonic renaissance, whence comes<br />

Prometheus? Although it might sound initially odd to modern ears, to some <strong>of</strong> its first<br />

readers <strong>Goethe</strong>’s Prometheus was a manifesto <strong>of</strong> Spinozism. Indeed, Prometheus<br />

became one <strong>of</strong> the most famous documents <strong>of</strong> late eighteenth-century neo-Spinozism,<br />

owing to the part it played in F.H. Jacobi’s 1785 Über die Lehre des Spinoza in<br />

Briefen an den Herrn Moses Mendelssohn 7 . Jacobi’s Briefe, containing a reported<br />

confession <strong>of</strong> Spinozism by G.E. Lessing, sparked the Spinozismusstreit, the<br />

repercussions <strong>of</strong> which were felt for three decades in German philosophy. Moreover,<br />

it was, Jacobi claimed, a copy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Goethe</strong>’s Prometheus which gave rise to Lessing’s<br />

admission. After Lessing praises the poem, the conversation continues (as reported by<br />

Jacobi):<br />

Lessing: I mean [Prometheus] is good in a different way… <strong>The</strong> point <strong>of</strong> view from<br />

which the poem is treated is my own point <strong>of</strong> view… <strong>The</strong> orthodox concepts <strong>of</strong><br />

the Divinity are no longer for me, I cannot stomach them. Hen kai pan! I know <strong>of</strong><br />

nothing else. That is also the direction <strong>of</strong> the poem, and I must confess I like it<br />

very much.<br />

I: <strong>The</strong>n you must be pretty well in agreement with Spinoza.<br />

Lessing: If I have to name myself after anyone, I know <strong>of</strong> nobody else. (Jacobi,<br />

1994, p. 187)

Beginning from <strong>Goethe</strong>’s Prometheus, Lessing proceeds directly to a confession <strong>of</strong><br />

his own allegiance to Spinozism. Just like <strong>Goethe</strong>, he claims, ‘I too am a disciple <strong>of</strong><br />

Spinoza.’<br />

What is strange is why Lessing should think Prometheus is obviously Spinozist or<br />

promotes in any way a Spinozist worldview. 8 Lessing’s own explanation that the hen<br />

kai pan <strong>of</strong> Spinoza’s monism is somehow implicitly present in the poem seems, on the<br />

face <strong>of</strong> it, patently false. <strong>The</strong> poem speaks <strong>of</strong> gods and is imbibed with the<br />

polytheistic worldview <strong>of</strong> the Greeks. It in no way questions the existence <strong>of</strong> these<br />

multiple divinities. 9 What Prometheus interrogates is not so much the metaphysical<br />

assumptions <strong>of</strong> theist or even polytheist worldviews, but their ethics. <strong>The</strong> gods<br />

obstruct humanity’s joyous pursuit <strong>of</strong> its earthly existence with their ressentiment;<br />

Prometheus’ stealing <strong>of</strong> the heavenly fire is a symbolic liberation from dependence on<br />

the gods—freeing humanity to increase its joy through its own activity. Prometheus<br />

allows the individual to desire as individual, free from the gods.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> this may just about sound Spinozist; however, to those involved in the early<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> the Spinoza renaissance in 1770s and 1780s Germany (like Lessing) it was<br />

the very essence <strong>of</strong> Spinozism. It is, however, crucial to stress that the Spinozist<br />

reading is one Lessing imposes on <strong>Goethe</strong>’s text; there is no evidence that <strong>Goethe</strong> at<br />

this period subscribed to Lessing’s ‘ethical neo-Spinozism’ or intended Prometheus to<br />

be Spinozist in any way, shape or form. 10 Indeed, in 1785 he firmly reprimanded<br />

Jacobi for implicating his poetry in this controversy (1919, IV/7:212-4). What<br />

complicates the picture somewhat, however, is that in the early 1780s (around seven<br />

years after writing Prometheus) <strong>Goethe</strong> did become an important figure in the German

Spinoza revival; this is one <strong>of</strong> the reasons why, in fact, Jacobi employed <strong>Goethe</strong>’s<br />

poetry in his critique <strong>of</strong> contemporary Spinozism. However, it is important to note<br />

that, despite the fame Prometheus was to have as a manifesto <strong>of</strong> Spinozism, it was<br />

most likely not intended as such.<br />

This <strong>of</strong> course merely adds to questions why Lessing did call <strong>Goethe</strong>’s Prometheus<br />

Spinozist and hopefully this will become clearer as the essay progresses. In the<br />

meantime, we can preliminarily conclude from the initial juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> Ganymed<br />

and Prometheus that <strong>Goethe</strong>’s early poetry exhibits two distinct lines <strong>of</strong> thought: one,<br />

in line with the neoplatonic revival <strong>of</strong> his day, conceives the appropriate relation to<br />

God to reside in fusion. <strong>The</strong> other line <strong>of</strong> thought, however, contests this: Prometheus<br />

asserts the need to rebel against such a pious ethos, to keep one’s distance and remain<br />

free as human. Prometheus rebels against the all-embracing oneness <strong>of</strong> Ganymed in<br />

the name <strong>of</strong> the multiple.<br />

[A] <strong>The</strong> <strong>Herder</strong>/Hemsterhuis Debate<br />

<strong>The</strong> next ‘scene’ I explore furthers this tension between neoplatonic piety and neo-<br />

Spinozist impiety. In 1781, J.G. <strong>Herder</strong> wrote a short appendix to a 1770 work by<br />

François Hemsterhuis: Liebe und Selbstheit (Ein Nachtrag zum Briefe des Herr<br />

Hemsterhuis über das Verlangen) 11 . At issue was the monopoly neoplatonism held on<br />

the God/human relation. <strong>Herder</strong> takes Hemsterhuis (as representative <strong>of</strong> this<br />

neoplatonism) to task for advocating a self-destructive conception <strong>of</strong> piety, and in its<br />

place <strong>Herder</strong> begins to articulate an alternative, neo-Spinozist model <strong>of</strong> friendship.

[B] Hemsterhuis’ Lettre sur les désirs<br />

To begin, therefore, it is worth summarising the argument <strong>of</strong> Hemsterhuis’ Lettre sur<br />

les désirs. 12 Like all Hemsterhuis’ work, this piece consists in (what one critic has<br />

called) ‘a mixture <strong>of</strong> empiricism and Platonism’ (di Giovanni, 1994, p. 47).<br />

Hemsterhuis is very influenced by the mechanistic sensualism <strong>of</strong> his French<br />

contemporaries and his vocabulary is theirs, but beneath this empiricist terminology<br />

there resides a neoplatonic metaphysics. While, it must be admitted, Hemsterhuis’<br />

neoplatonism is crude, his work was still perfectly recognisable to his contemporaries<br />

as providing an eighteenth-century reworking <strong>of</strong> neoplatonic thought. Indeed,<br />

<strong>Herder</strong>’s Liebe und Selbstheit is exclusively concerned with Hemsterhuis’<br />

neoplatonism.<br />

At the beginning <strong>of</strong> the work, Hemsterhuis states, ‘<strong>The</strong> absolute goal <strong>of</strong> the soul,<br />

when it desires, is the most intimate and most perfect union <strong>of</strong> its own essence with<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the desired object.’ (Hemsterhuis, 1846, p. 54) Again, the comparison with<br />

Plotinus is revealing: as for Plotinus so for Hemsterhuis, to desire something is to<br />

desire to become one with it. Moreover, and also in line with Plotinus, such desire is a<br />

force <strong>of</strong> attraction inherent in all matter. A tendency towards oneness forms the<br />

essence <strong>of</strong> all beings—animate and inanimate. Whenever there is more than one<br />

discrete object dispersed in the world, the natural inclination will be to rid the world<br />

<strong>of</strong> the multiple until only the One remains. <strong>The</strong> ultimate goal <strong>of</strong> this tendency is ‘that<br />

two substances will become united to such an extent that any notion <strong>of</strong> duality will be<br />

destroyed.’ (ibid, 53) As <strong>Herder</strong> summarises, ‘Hemsterhuis demonstrated that love<br />

unites beings and that all longing, all desire, strives only for this union, as the only<br />

possible pleasure <strong>of</strong> separated beings.’ (1994, 4:408; 1993, p. 112)

<strong>The</strong> similarity to Ganymed is immediately obvious: ethics is ruled by the One. Lettre<br />

sur les désirs can be read as a theoretical elaboration <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> the philosophical and<br />

theological presuppositions behind <strong>Goethe</strong>’s poem; in fact, Hemsterhuis’ work is<br />

representative <strong>of</strong> the neoplatonic renaissance as a whole which was then sweeping<br />

Germany. 13 All ethics, even our relation to God, remains bound to the model <strong>of</strong> union.<br />

Just as in Ganymed, piety is the natural desire for all-embracing oneness.<br />

Every mental and physical event can be explained by striving for union. Much <strong>of</strong><br />

Hemsterhuis’ account here is explicitly dependent on Aristophanes and Socrates’<br />

myths <strong>of</strong> desire in the Symposium. All the physical behaviour <strong>of</strong> animate organisms is<br />

directed towards sexual union, or, as Hemsterhuis puts it, ‘all the physical means the<br />

soul has at its disposal are used in its tendency towards a union <strong>of</strong> essences’ (1846, p.<br />

58). 14 Moreover, again, following traditional Platonic thought, Hemsterhuis goes on to<br />

distinguish such sexual union from intellectual union and assigns the telos <strong>of</strong> reality to<br />

the latter. <strong>The</strong> fusion <strong>of</strong> mind and world (or, even better, mind and mind) provides the<br />

ultimate standard for all activity. It explains (among other things) art, friendship, love<br />

and religion. In fact, Hemsterhuis ranks these different phenomena on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

their capacity for unification:<br />

One will love a beautiful statue less than one’s friend, one’s friend less than one’s<br />

mistress and one’s mistress less than the Supreme Being. It is for this reason that<br />

religion gives rise to more intense enthusiasts than love, love more than friendship<br />

and friendship more than desire for purely material things. (ibid, p. 54)

<strong>The</strong> reasoning behind this hierarchy is to be found in the maxim, ‘<strong>The</strong> degree <strong>of</strong><br />

attractive force is always measured by the degree <strong>of</strong> homogeneity to the desired<br />

object, and this degree <strong>of</strong> homogeneity consists in the degree to which perfect union is<br />

possible.’ (ibid, p. 54) <strong>The</strong> extent to which I desire an object is determined by the<br />

likely union I can achieve with it. Hence, friendship is inferior to love because the<br />

complete fusion <strong>of</strong> two beings into one is more the preserve <strong>of</strong> love than <strong>of</strong> friendship.<br />

Friendship is, on this account, merely an imperfect form <strong>of</strong> love; a less intense desire<br />

for complete union.<br />

<strong>The</strong> above also provides Hemsterhuis with the beginnings <strong>of</strong> an account <strong>of</strong> the<br />

relation between humanity and God (and so <strong>of</strong> piety). God is the being into which one<br />

can be most easily absorbed without remainder. Through religion desire can be most<br />

easily consummated; it is thus the most proper channel for human desire. Here,<br />

‘homogeneity appears perfect’ (ibid, p. 55). In consequence, religion is the very<br />

paradigm and the most natural form <strong>of</strong> human behaviour. <strong>The</strong>re is nothing more<br />

proper to humanity than fusing with God.<br />

However, Hemsterhuis ends his Lettre having hit a snag. If all tends towards<br />

‘coagulation’ (and the human/God relation is the paradigm example <strong>of</strong> this), why then<br />

do there still remain discrete, individual entities? <strong>The</strong> question, as Hemsterhuis notes,<br />

is even more problematic with respect to creation: if love is a tendency towards union<br />

and God loves his creatures infinitely, why then did He disperse them into isolated<br />

individuals when creating them? Hemsterhuis has no answer to such questions;<br />

instead, he concludes as follows,

I conclude from this that everything visible and sensible is in fact in an artificial<br />

state, since, tending eternally to union but remaining always composed <strong>of</strong> isolated<br />

individuals, the nature <strong>of</strong> everything continues to be eternally in a state <strong>of</strong><br />

contradiction… Since everything tends naturally towards unity, then there must be<br />

a foreign force who has decomposed the total unity into individuals and this force<br />

is God. It would require the most extravagant madness to want to penetrate to the<br />

essence <strong>of</strong> this impenetrable being. (ibid, p. 68)<br />

In the end, individuation remains an insoluble, divine mystery for Hemsterhuis. <strong>The</strong><br />

force <strong>of</strong> inertia which impedes the desire to unite is a surd he is unable to theorise. It<br />

belongs to the suprarational realm <strong>of</strong> the divine which human thought cannot access.<br />

[B] <strong>Herder</strong>’s Postscript<br />

<strong>Herder</strong>’s Liebe und Selbstheit picks up the thread <strong>of</strong> Hemsterhuis’ argument precisely<br />

at this point. <strong>Herder</strong> takes it upon himself to provide an answer to this mystery, a<br />

theoretical basis to the question <strong>of</strong> why there are individuals. In so doing, he ends up<br />

contesting the very neoplatonic model <strong>of</strong> piety Hemsterhuis was attempting to justify.<br />

<strong>Herder</strong>’s essay is explicitly intended as a mere ‘postscript’, filling in the gaps <strong>of</strong><br />

Hemsterhuis’ description <strong>of</strong> reality. Yet, as we know from other postscripts (such as<br />

Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript), such a genre <strong>of</strong> writing not only<br />

adds to the original but tends to end up supplanting it. This is, in fact, the case here: in<br />

providing a theory <strong>of</strong> the pleasure <strong>of</strong> individual existence, <strong>Herder</strong> ultimately<br />

invalidates Hemsterhuis’ neoplatonism. <strong>Herder</strong>, that is, depicts a competing view <strong>of</strong><br />

reality—in place <strong>of</strong> Hemsterhuis’ metaphysics <strong>of</strong> the One, he describes an alternative<br />

ethics <strong>of</strong> friendship.

<strong>The</strong> crux <strong>of</strong> <strong>Herder</strong>’s disagreement is contained in the following claim,<br />

<strong>The</strong> more spiritual the pleasure, the more it endures and the more its object also<br />

endures outside <strong>of</strong> us… [the more] an object exists and continues to exist outside<br />

<strong>of</strong> us and can only really become one with us metaphorically, that is, hardly or not<br />

at all. (1994, 4:409; 1993, p. 113)<br />

Hemsterhuis asserted that desire for union (and so the possibility <strong>of</strong> union) increased<br />

the more spiritual the desire became; <strong>Herder</strong> here—under the pretext <strong>of</strong> summarising<br />

Hemsterhuis’ thought—gives a diametrically opposed analysis. <strong>The</strong> more spiritual a<br />

desire, the less explaining it by means <strong>of</strong> fusion makes sense, for such fusion is, in<br />

fact, less possible here. Moreover, in a complete disregard for Hemsterhuis’ actual<br />

position, <strong>Herder</strong> suggests this is a good thing: pious desire for union is not something<br />

to be positively valued, but is rather merely the model for ‘crude’ desires. Desire for<br />

union is a ‘brief, deceptive illusion’ (ibid, 4:416; p. 116). Spiritual desires are to be<br />

valued more highly precisely because they obey a very different model and are not<br />

determined by the figure <strong>of</strong> the One.<br />

<strong>The</strong> reason for this is the self-destructiveness <strong>of</strong> neoplatonic piety. As Aristophanes<br />

already noted in the Symposium, when one unites with the object, all pleasure is at an<br />

end, for the subject/object relation is annulled. <strong>The</strong> same problem holds for<br />

Hemsterhuis who follows the Symposium closely: desire for the One destroys desire.<br />

‘It is impossible for man to flow together with everything like mud’—and stay man,<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> writes (ibid, 4:422; p. 119). Hence, <strong>Herder</strong> argues that spiritual pleasures are

an improvement upon carnal ones precisely because there is no union and so the<br />

desired object goes on persisting. It is for this reason desires, pleasures and even ways<br />

<strong>of</strong> relating to God that do not tend towards unity are to be preferred—and at this point<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> leaves Hemsterhuis far behind him.<br />

In opposition to Hemsterhuis, <strong>Herder</strong> introduces his alternative: friendship, which will<br />

go on to become the key motif in what follows.<br />

Friendship! What a… holy bond it is! It links hearts and hands together into one<br />

common purpose… It [unlike love] is ongoing and arduous… Love destroys<br />

either itself or its object with penetrating, consuming flames, and both lover and<br />

beloved then lie there like a pile <strong>of</strong> ashes. But the fire <strong>of</strong> friendship is pure,<br />

refreshing, human warmth. (ibid, 4:410-1; pp. 113-4)<br />

In a reworking <strong>of</strong> Classical and humanist discourses on the eros/philia distinction,<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> maintains that, while love designates those desires that tend towards union,<br />

friendship is the name <strong>of</strong> another, preferable ethical relation—which does not destroy<br />

its object, but allows it to persist. In friendship, desire does not obliterate itself. <strong>The</strong><br />

crucial word is ‘ongoing’: friendship is the pleasure between individuals as<br />

individuals; unlike love, such pleasure is not premised on the ultimate dissolution <strong>of</strong><br />

the desiring subject and desired object—but on their perpetuation. Unlike love which<br />

is caught up in the self-destructive paradox that desire is for an end <strong>of</strong> desire (that, in<br />

other words, the individual desires her own dissolution), friendship maintains the<br />

integrity and distinctness <strong>of</strong> the subject and object even in the achievement <strong>of</strong>

pleasure. Friendship circumvents the One in favour <strong>of</strong> the multiple. Friendship is<br />

‘endless’—an infinite, ‘arduous’ task which never reaches completion.<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> elucidates friendship through opposing ‘common purpose’ to union. What is<br />

sought is not for two individuals to become the same, to meld into one another, but<br />

rather collaboration—the mutual and reciprocal interchange <strong>of</strong> ideas that helps form<br />

each individual in divergent ways. <strong>Herder</strong> writes, ‘<strong>The</strong> two flames on one altar play<br />

into one another, they jubilantly lift and carry one another… In general a life in<br />

common is the mark <strong>of</strong> true friendship: the disclosing and sharing <strong>of</strong> hearts’ (ibid,<br />

4:412; p. 114). Perhaps we could gloss <strong>Herder</strong>’s comments anachronistically by<br />

quoting Michèle Le Doeuff’s allusion to the collaborative relationship <strong>of</strong> John Stuart<br />

Mill and Harriet Taylor. She writes in <strong>The</strong> Sex <strong>of</strong> Knowing,<br />

However far we go back in the history <strong>of</strong> their relationship, Harriet Taylor never<br />

was a disciple <strong>of</strong> John Stuart Mill. Still less was she his creation… Each stood up<br />

to the other, neither was completely under the “influence” <strong>of</strong>, or “incorporated”<br />

by, the other, but each had to defend her/himself against the other, each had a<br />

slight tendency to want too much from the other. (Le Doeuff, 2003, p. 217)<br />

Just as for <strong>Herder</strong>, so too for Le Doeuff it is not the ‘incorporation’ <strong>of</strong> one individual<br />

into another which provides the ethical telos <strong>of</strong> life, but rather collaboration between<br />

two distinct and competing individual thinkers—not discipleship but friendship. It is<br />

the pleasure the individual as individual takes in another.

Thus, having begun with the intention <strong>of</strong> providing a mere ‘postscript’ to<br />

Hemsterhuis’ Lettre sur désirs, <strong>Herder</strong> can conclude after only two pages, ‘Even love<br />

serves friendship… Friendship appears to me to be the climax <strong>of</strong> every desire.’ (1994,<br />

4:413; 1993, pp. 114-5) In direct opposition to Hemsterhuis, instead <strong>of</strong> seeing<br />

friendship as an imperfect form <strong>of</strong> love, <strong>Herder</strong> conceives love as an imperfect form<br />

<strong>of</strong> friendship! And this is precisely because friendship is directed to other things than<br />

to union: friendship is grounded in the mutual interchange <strong>of</strong> individuals (‘this pulse<br />

<strong>of</strong> passive and active’ (ibid, 4:420; p. 118)), rather than in an illusory and unhealthy<br />

ideal <strong>of</strong> becoming-one. As <strong>Herder</strong>’s concludes,<br />

Where the destruction <strong>of</strong> the other ends there first begins a freer, more beautiful<br />

pleasure, a cheerful coexistence <strong>of</strong> many creatures who mutually seek and love<br />

one another… Consonant, not unisonant, tones must be the ones that create the<br />

melody <strong>of</strong> life and pleasure. (ibid, 4:420-1; pp. 118-9)<br />

In a matter <strong>of</strong> pages, the self-destructive piety <strong>of</strong> Hemsterhuis is thoroughly<br />

transformed into the impiety <strong>of</strong> the burgeoning philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion. Desire for<br />

fusion must be tempered by a respect for multiplicity. <strong>Discipline</strong> is privileged over<br />

consummation: what is truly ethical is that which battles against desires for union in<br />

the name <strong>of</strong> the individual will.<br />

In Liebe und Selbstheit, however, <strong>Herder</strong> is not only directing his attack outwards<br />

against Hemsterhuis, he is also interrogating his own tendencies to neoplatonic piety.<br />

Just like with <strong>Goethe</strong>, there is an internal conversation being pursued between piety<br />

and impiety. <strong>The</strong> ideal <strong>of</strong> friendship is pitched in combat against <strong>Herder</strong>’s own

attraction to a neoplatonic ethics <strong>of</strong> universal attraction. Not only are there examples<br />

from elsewhere in <strong>Herder</strong>’s work <strong>of</strong> him enthusiastically embracing this doctrine,<br />

even in Liebe und Selbstheit itself there are neoplatonic flourishes. <strong>Herder</strong><br />

apostrophises, for example,<br />

To whom can I ascend… except to you, great universal Mother, tender supreme<br />

Father!… Who ought not but to love you, for every creature draws toward you,<br />

points to you? And yet who can love you as one should, since one drowns in the<br />

sea <strong>of</strong> your thoughts and your presentient feelings and sinks into the deepest<br />

depths only beyond oneself… This eternal pull <strong>of</strong> your heart to mine is for me an<br />

innate guarantee <strong>of</strong> my eternal affection for you. (ibid, 4:417-8; p. 117)<br />

Liebe und Selbstheit is therefore not only a polemic against Hemsterhuis, but also a<br />

self-examination. Enacted within the very text <strong>of</strong> the essay is the struggle between<br />

friendship and love, impiety and piety.<br />

Hence, immediately after the above rhapsody, <strong>Herder</strong> insists, ‘Even in the current <strong>of</strong><br />

divine love, the heart remains a mere human heart.’ (ibid, 4:419; p. 117) This claim is<br />

at the centre <strong>of</strong> <strong>Herder</strong>’s interpretation <strong>of</strong> piety and, more specifically, <strong>of</strong> his attempt<br />

to apply his ethics <strong>of</strong> friendship to the human/God relation. Religion should not be<br />

directed towards a unio mystica or ascent to the divine, in which the human self is<br />

annihilated and absorbed into the Godhead. Rather, religion should insist that the<br />

individual relates to God as individual—on a purely human level, without need for<br />

apotheosis or transfiguration. ‘We always remain creatures,’ <strong>Herder</strong> insists (ibid,

4:423; p. 120). Humanity’s finitude can and should never be overcome. In relating to<br />

God, the individual must insist on remaining separate and retaining her integrity:<br />

We are individual beings, and we must be so if we do not want to give up the<br />

ground <strong>of</strong> every pleasure—our own consciousness <strong>of</strong> pleasure—and if we do not<br />

want to lose ourselves in order to find ourselves again in another being that we<br />

never are and never can be. Even if I were to lose myself in God, as mysticism<br />

strives to do, and were to lose myself in God without any further feeling or<br />

consciousness <strong>of</strong> myself, then I would no longer be experiencing pleasure. <strong>The</strong><br />

deity would have devoured me; and instead <strong>of</strong> me, the deity would have<br />

experienced the pleasure. (ibid, 4:419; p. 118)<br />

To affirm the neoplatonist notion <strong>of</strong> piety is to affirm a ‘devouring God’ who puts an<br />

end to all individual existence. It is to affirm self-destruction. Hence, instead <strong>of</strong><br />

desiring union with God, we should desire to co-exist with God and ‘peacefully and<br />

mutually seek to take pleasure in one another’ (ibid, 4:420; p. 118). We should exist<br />

autonomously and separately. <strong>The</strong> ideal is for friendship with God, rather than love <strong>of</strong><br />

God. It is the ideal for ‘the way we are in this world’ (ibid, 4:422; p. 119)—a refusal<br />

<strong>of</strong> the utopia <strong>of</strong> apotheosis in favour <strong>of</strong> continuing ethical work in the finite.<br />

Even with regard to God, therefore, humanity must achieve a ‘modulation and<br />

balance.’ (ibid, 4:420; p. 118) We will see <strong>Kant</strong> make very similar claims below.<br />

Friendship with God (as well as other finite individuals) is ‘not possible except<br />

between creatures who are mutually free and consonant, but not unisonant, let alone<br />

identical’ (ibid, 4:423; p. 120). Only by restraining our desires and holding up

alternative ideals than union can ‘the most dangerous dream’ <strong>of</strong> infinite oneness be<br />

avoided. Neoplatonic piety and the increasing engulfment <strong>of</strong> God on which it is<br />

premised should be thwarted, in favour <strong>of</strong> keeping God at a distance. Humanity<br />

should strive for an artificial and improper relation to the deity which does not<br />

succumb to natural attraction. Moreover, by means <strong>of</strong> his ethics <strong>of</strong> friendship, <strong>Herder</strong><br />

claims to have explained the mystery <strong>of</strong> individuation Hemsterhuis was unable to<br />

solve: individual existence is necessary for the experience <strong>of</strong> a different, more<br />

valuable relation than that which unification brings. Individuation is necessary for<br />

friendship, and so <strong>Herder</strong> concludes, ‘<strong>The</strong> supreme good that God could grant all<br />

creatures was and is individual existence.’ (ibid, 4:423-4; p. 120)<br />

[B] ‘Ethical Neo-Spinozism’<br />

<strong>The</strong> dispute between the superiority <strong>of</strong> friendship and love is, as I have mentioned, <strong>of</strong><br />

classical origin and was preserved in the humanist tradition. However, surprisingly, it<br />

is not on this tradition that <strong>Herder</strong> draws (at least explicitly); instead, Liebe und<br />

Selbstheit is littered with allusions to Spinoza’s Ethics. For example, <strong>Herder</strong> writes,<br />

By giving and acting, rather than receiving and being passive, our existence<br />

necessarily will become ever freer and more effective from stage to stage, our<br />

pleasure will become less damaging and destructive, and we will learn to taste<br />

ever more joy. (ibid, 4:423; p. 120)<br />

This juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> joy, activity, pleasure and freedom is extremely Spinozist. For<br />

example, Spinoza writes, ‘By joy, therefore, I shall understand… that passion by<br />

which the mind passes to a greater perfection’ (1994, IIIP11D), and by ‘greater

perfection’ Spinoza means the becoming more active <strong>of</strong> the mind (ibid, IIIP11) as<br />

well as its becoming freer (ibid, VP36). Linked here is Spinoza’s understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

conatus. When <strong>Herder</strong> exclaims, ‘You are indeed a limited, individual creature… Pull<br />

yourself together and strive on!’ (1994, 4:420; 1993, p. 118), he alludes to Spinoza’s<br />

claim that ‘the striving by which each thing strives to persevere in its being is nothing<br />

but the actual essence <strong>of</strong> the thing.’ (1994, IIIP6) Just like <strong>Herder</strong>, Spinoza conceives<br />

<strong>of</strong> individuals in terms <strong>of</strong> an endless striving; moreover, such desire is not for<br />

something that would annihilate the individual—such as fusion with or apotheosis<br />

into the divine—rather the desire is essentially finite. It is a desire to be as active and<br />

joyful as possible within the limits <strong>of</strong> finitude.<br />

However, (as with <strong>Goethe</strong>’s Prometheus) to call <strong>Herder</strong>’s model ‘Spinozist’ seems<br />

strange—for is not Spinoza the ultimate philosopher <strong>of</strong> the One, the most rigorous and<br />

extreme monist known to Western philosophy? How then can <strong>Herder</strong>’s defence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

multiple against the One be characterised as Spinozist? <strong>Herder</strong>, I seem to be arguing,<br />

is using Spinoza to argue against monism. Moreover, it is clear that <strong>Herder</strong> is<br />

unconcerned with historical and philosophical accuracy here. For example, the<br />

implicit contrast he establishes between Spinozism and neoplatonism, while plausible<br />

in some respects, cannot be maintained as sharply as he intends. Second, to align<br />

Spinoza with an ethics <strong>of</strong> friendship in opposition to an ethics <strong>of</strong> love is once more<br />

puzzling: since love (especially ‘the intellectual love <strong>of</strong> God’) plays a crucial role in<br />

the latter parts <strong>of</strong> the Ethics, while the concept <strong>of</strong> friendship does not (1994, IIIP59S,<br />

IVP37S1). <strong>Herder</strong>’s Spinoza is therefore inaccurate; indeed, ‘Spinoza’ is little more<br />

than the name <strong>of</strong> a ‘heretic’ whose attack on Orthodoxy <strong>Herder</strong> is here repeating (on a<br />

smaller scale). Spinoza is an ideological ally in the destruction <strong>of</strong> traditional

neoplatonic forms <strong>of</strong> piety and the establishment <strong>of</strong> a new, modern alternative based<br />

on autonomy, separation and ultimately indifference towards the divine.<br />

To comprehend this ‘ideological’ employment <strong>of</strong> Spinoza, we must turn to the context<br />

<strong>of</strong> Liebe und Selbstheit—a burgeoning ‘ethical neo-Spinozism’ in 1770s and early<br />

1780s Germany. <strong>The</strong>re were a number <strong>of</strong> German thinkers at this period (including<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> and Lessing) who took part in a recovery <strong>of</strong> Spinoza’s thought, but did so by<br />

‘reading the Ethics back-to-front’. Instead <strong>of</strong> concentrating on Parts I and II <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Ethics with their stress on metaphysics and the ultimate unity <strong>of</strong> all reality, this<br />

‘ethical neo-Spinozism’ sought to reinvent Spinozism by appropriating insights from<br />

the latter parts <strong>of</strong> the work on human desires and emotions. Avoiding Spinoza’s<br />

pantheism, these thinkers were far more interested in his accounts <strong>of</strong> conatus and<br />

joyful passions.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, prior to the pantheism controversy in 1785—when Jacobi published his<br />

Briefe and so when Spinoza-reception went mainstream—there was a period in which<br />

Spinoza was used as a resource for moral philosophy. 15 During the 1770s and early<br />

1780s, <strong>Herder</strong> frequently makes clear his adherence to the later portions <strong>of</strong> the Ethics.<br />

For example, he writes,<br />

Without doubt Spinoza was no Christian and no enthusiast. But take the purely<br />

ethical part <strong>of</strong> his Ethics, quite separately from his metaphysics, and see… in the<br />

simplest and most powerful way [Christian ethics] confirmed by facts, and<br />

grounded in its whole design. (Quoted in Bell, 1984, p. 55)

Or again, J.G. Müller reports the following conversation that took place between him<br />

and <strong>Herder</strong> in 1781:<br />

We talked <strong>of</strong> Spinoza… <strong>The</strong> first, theoretical part was, [<strong>Herder</strong>] said, the heretical<br />

one, but the second, ethical part contained the purest, most sublime ethic. (Quoted<br />

in Bell, 1984, p. 67)<br />

Prior to 1785 therefore the German Spinoza-reception is dominated by ethics—<br />

concentrating on Spinoza’s doctrines <strong>of</strong> conatus, joyful passion and freedom, at the<br />

expense <strong>of</strong> his monism. During this initial phase, the Ethics are read back-to-front. It<br />

is only in 1785 that Spinoza’s metaphysics and pantheism becomes a major issue in<br />

German thought. Indeed, Jacobi’s Briefe, which single-handedly made Spinozist<br />

metaphysics so contentious, is (amongst other things) an attack on <strong>Herder</strong>’s ‘ethical<br />

neo-Spinozism’.<br />

[B] <strong>The</strong> Neoplatonic Renaissance<br />

<strong>The</strong> argument <strong>of</strong> this essay necessitates a further claim: ‘ethical neo-Spinozism’ was<br />

generated in reaction to another more prominent renaissance <strong>of</strong> the time—a revival <strong>of</strong><br />

neoplatonic philosophy. That is, while a renewed interest in Spinoza was, it is true,<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong> German thought in the 1770s and 1780s, even more noticeable is the<br />

significance neoplatonism took on during that period. Indeed, <strong>Herder</strong> himself was<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>oundly influenced by both movements and, as such, his work <strong>of</strong> this period bears<br />

the scars <strong>of</strong> the struggle between these two competing renaissances.

Let me flesh this out by returning to François Hemsterhuis and his context.<br />

Hemsterhuis was the leading thinker <strong>of</strong> the ‘Münster circle’—a group <strong>of</strong> mystics and<br />

theologically-inclined thinkers residing in Münster on the patronage <strong>of</strong> the Princess<br />

Gallitzen. ‘A neoplatonist in the tradition <strong>of</strong> the Cambridge Platonists and<br />

Shaftesbury’ (Gusdorf, 1976, p. 280), Hemsterhuis’ blend <strong>of</strong> empiricism and<br />

neoplatonism became representative <strong>of</strong> this group’s work. <strong>The</strong> circle was particularly<br />

influential during the late eighteenth century: Hamann moved to Münster in the last<br />

year <strong>of</strong> his life to participate in the group, Jacobi was also closely involved and<br />

<strong>Goethe</strong> and <strong>Herder</strong> were regular visitors. 16 As late as the 1790s, Novalis claimed<br />

Hemsterhuis as his favourite philosopher and devoted a ‘study’ to his work (1988,<br />

2:360-78). Indeed, Gusdorf has concluded, ‘Through the intermediary <strong>of</strong> Jacobi<br />

[among others], Hemsterhuis’ influence spread to Lessing, <strong>Herder</strong>, <strong>Goethe</strong>, Schiller<br />

and the young Romantics.’ (1976, p. 281)<br />

Hemsterhuis’ legacy was so great, I contend, precisely because his neoplatonism<br />

chimed in so well with the intellectual currents <strong>of</strong> the time. As Arthur Lovejoy has<br />

claimed, ‘a revival <strong>of</strong> the direct influence <strong>of</strong> neoplatonism was one <strong>of</strong> the conspicuous<br />

phenomena <strong>of</strong> German thought in the 1790s’ (1936, pp. 297-8) 17 ; however, this<br />

revival should be antedated by at least thirty years. Beiser, for example, has shown<br />

how the German reception <strong>of</strong> Plato began in the 1750s:<br />

It was in 1757 that Winckelmann read Plato who became one <strong>of</strong> the central<br />

influences on his aesthetics. By the 1760s interest in Plato had grown enormously.<br />

<strong>The</strong> writings <strong>of</strong> Rousseau and Shaftesbury, which were filled with Platonic<br />

themes, began to have their impact. It was also in the 1760s that Hamann, <strong>Herder</strong>,

Winckelmann, Wieland and Mendelssohn all wrote about Plato or Platonic<br />

themes. By the 1770s Plato had become a popular author. New editions and<br />

translations <strong>of</strong> his writings frequently appeared. (2002, p. 365)<br />

Bearing this context in mind, <strong>Herder</strong>’s Liebe und Selbstheit provides a fascinating<br />

microcosm <strong>of</strong> the times. In it, burgeoning ‘ethical neo-Spinozism’ is pitched in battle<br />

against the far more established neoplatonic renaissance. In this text, what is more, it<br />

becomes clear precisely why <strong>Herder</strong> rejects the prevalent neoplatonism interpretation<br />

<strong>of</strong> piety. It is because it could not account for the desire the individual experiences as<br />

an individual. Instead, the neoplatonism <strong>of</strong> the time merely saw individual existence<br />

as a transitory epiphenomenon <strong>of</strong> the One. Neoplatonic piety was self-destructive.<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> uses Spinoza to ground an ethics <strong>of</strong> the multiple so as to resolutely counter<br />

such neoplatonism. He uses Spinoza to sketch the ethical figure <strong>of</strong> ‘the not-One’ in<br />

which the mutual interchange <strong>of</strong> discrete individuals is the telos <strong>of</strong> life. He moves<br />

therefore towards a very different mode <strong>of</strong> piety. <strong>Herder</strong>’s Liebe und Selbstheit stages<br />

the ethical conflict <strong>of</strong> the period between love and friendship, between Plato and<br />

Spinoza. 18<br />

[A] <strong>Kant</strong>ian Pudor Pietatis<br />

<strong>Kant</strong>’s late philosophy—despite the notoriety <strong>of</strong> the pantheist controversy—takes<br />

place in a very different context. As he admitted when the controversy broke out, he<br />

had never really read Spinoza’s Ethics. It would be futile then to wish to discover<br />

Spinozist elements in his thought. However, despite this lack <strong>of</strong> direct influence, there<br />

are very interesting parallels between what <strong>Kant</strong> says about friendship and the

human/God relation in the Metaphysik der Sitten and ‘ethical neo-Spinozism’. <strong>Kant</strong><br />

too attacks the prevalent self-destructive piety preserved in neoplatonic thought in<br />

favour <strong>of</strong> an alternative based on friendship. What is more, <strong>Kant</strong> stresses that the<br />

disinterested quality <strong>of</strong> this alternative; he insists that his new form <strong>of</strong> piety keeps its<br />

distance from God.<br />

Indeed, the parallels between <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong>’s alternative become even more<br />

noteworthy if one bears in mind, what Blumenberg has dubbed, the ‘late anti-<br />

Platonism’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kant</strong>’s thought (1987, p. 56). <strong>Kant</strong>’s 1796 essay, On a Recently<br />

Prominent Tone <strong>of</strong> Superiority in Philosophy, is evidence <strong>of</strong> this. It responds to the<br />

ever more prominent neoplatonic renaissance <strong>of</strong> late eighteenth century Germany, and<br />

berates ‘the new Platonists’ and their ‘latest mystico-Platonic idiom’ (2002, 8:399). 19<br />

Directly, <strong>Kant</strong> is reacting to J.G. Schlosser and F.L. Stolberg, yet, more generally, this<br />

work is a ‘polemic against a contemporary neoplatonism’ (Blumenberg, 1987, p. 53),<br />

a reaction against the neoplatonic renaissance in general. Like <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Goethe</strong><br />

before him, <strong>Kant</strong> is uneasy with his era’s increasing use <strong>of</strong> neoplatonic philosophy<br />

and turns on it.<br />

While the concerns <strong>of</strong> On a Recently Prominent Tone are for the most part<br />

epistemological, this turn away from Plato is also prevalent (if implicit) in the<br />

Metaphysik der Sitten and other late ethical writings. It results in an obsessive<br />

concern for limits—especially limits on love and piety. Moreover, it also results in an<br />

alternative model for ethics based on friendship.<br />

[B] <strong>The</strong> Trouble with Love

In the lectures <strong>Kant</strong> gave on the Metaphysik der Sitten, he introduces the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

pudor pietatis (modesty <strong>of</strong> piety), and this idea <strong>of</strong> limiting one’s piety or love is a<br />

central refrain throughout the lecture course. For example, the final section devoted to<br />

‘Duties to God’ is shot through with the rhetoric <strong>of</strong> discipline. Its focus is the<br />

appropriate methods for the veneration <strong>of</strong> God: on the one hand, <strong>Kant</strong> insists, ‘Love<br />

towards God is the foundation <strong>of</strong> all inner religion’ (1997, 27:720); yet, he is equally<br />

insistent that such love must be understood in an extremely attenuated fashion:<br />

Love <strong>of</strong> God can be known only through our reason… <strong>The</strong>re can be no sensuous<br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> love without a concurrent pathological effect; to love practically means<br />

merely to perform one’s actions from duty… Love God tells us no more than to<br />

base our observance <strong>of</strong> laws, not merely on obedience, which produces the<br />

coercion and necessitation <strong>of</strong> the law, but on an inclination in conformity with<br />

what the law prescribes. (ibid, 27:721)<br />

While not the main focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kant</strong>’s attack (the Pietists <strong>of</strong> his youth probably hold that<br />

honour), contemporary neoplatonists like Hemsterhuis are implicitly condemned here.<br />

<strong>Kant</strong>ian love <strong>of</strong> God should not be confused with a desire—either sensible or<br />

intellectual—for increasing unity with the deity; rather, ‘love’ is diluted so as to<br />

‘mean merely’ a willing performance <strong>of</strong> duty. <strong>Kant</strong> goes on to distance his own<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> love from ‘enthusiastic’ conceptions <strong>of</strong> ‘fanatical love’ or ‘the claim<br />

to an immediate, intercourse, fellowship and social connection with God.’ (ibid,<br />

27:726) Love must be freed from its dependence on desire, especially carnal or<br />

natural desire. Only desireless love—love which thwarts our pious temptation to<br />

approach God—is moral. A new piety is here in the process <strong>of</strong> emerging, a piety

concerned with disciplining desire and becoming disinterested about God.<br />

Indifference replaces interest as the motivating theoretical force.<br />

Moreover, such restrictions on love <strong>of</strong> the divine lead also to limitations on piety<br />

itself, for <strong>Kant</strong>, like <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Goethe</strong> before him, identifies piety with a constant<br />

desire for union with God and a consequent withdrawal from the finite. <strong>Kant</strong> therefore<br />

makes clear, in opposition to all ‘religious fanatics’: ‘In practising religious we do<br />

not… find ourselves in a state <strong>of</strong> devotion, i.e. in a mood directed to the immediate<br />

contemplation <strong>of</strong> God, and withdrawn from all sensible objects.’ (ibid, 27:731)<br />

Fanaticism involves a withdrawal from the world, an attempt to live on a divine plane<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> a human one. Such fanaticism, <strong>Kant</strong> continues, runs the risk <strong>of</strong> bigotry and<br />

hypocrisy, for there is no means <strong>of</strong> distinguishing genuine and fake mystic<br />

experience. In all these problematic forms <strong>of</strong> religious display, there is ‘an ostentatio<br />

pietatis’, a shameless display <strong>of</strong> religious feeling. On the other hand, <strong>Kant</strong><br />

recommends a ‘pudor pietatis which consists in a bashfulness about avoiding in one’s<br />

actions any suspicion <strong>of</strong> bigotry.’ (ibid, 27:732) Religion consists not in the<br />

cultivation <strong>of</strong> piety, but instead in restraint <strong>of</strong> piety, the limitation <strong>of</strong> desire for God<br />

and <strong>of</strong> any ‘delusion’ concerning humanity’s ability to fuse with Him. 20<br />

<strong>Kant</strong> makes a similar point in the Religion. He berates the individual who believes<br />

that ‘to become a better human being… [he must] busy himself with piety (which is a<br />

passive respect <strong>of</strong> the divine law) rather than with virtue (which is the deployment <strong>of</strong><br />

one’s forces in the observance <strong>of</strong> the duty which he respects).’ Instead, <strong>Kant</strong> advises,<br />

‘It is this virtue, combined with piety, which alone can constitute the idea we<br />

understand by the word divine blessedness (true religious disposition).’ (1998, 6:201)

<strong>Kant</strong> here almost falls into contradiction: the correct religious disposition and so the<br />

way to achieve divine blessedness is not through piety! Piety is not the appropriate<br />

manner in which to relate to God; instead, it should take a role subordinate to the<br />

cultivation <strong>of</strong> virtue and only then is the ‘true religious disposition’ attained.<br />

Blessedness is not reached by means <strong>of</strong> piety alone.<br />

<strong>Kant</strong>’s central objection is the passivity <strong>of</strong> piety. Just like Ganymede, the pious<br />

individual waits expectantly to be embraced by the divine, whereas the virtuous<br />

individual is like Prometheus actively pursuing the ends dictated by human reason—<br />

not in the hope <strong>of</strong> some future apotheosis, but with the goal <strong>of</strong> living ethically in this<br />

world. <strong>The</strong> enthusiast, who expects a future fusion into the divine and escape from<br />

this world, renounces virtue. Eschatology here trumps ethics. 21<br />

[B] Friendship beyond Love<br />

In the published Metaphysik der Sitten itself, <strong>Kant</strong> goes even further—albeit<br />

implicitly. Friendship is here crowned as the ethical ideal in a manner extremely<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> <strong>Herder</strong>’s reaction to Hemsterhuis’ neoplatonism. 22 <strong>The</strong> Metaphysik der<br />

Sitten concludes with the highest form <strong>of</strong> relation that can exist between two subjects,<br />

and, <strong>Kant</strong> makes clear, this is not love but friendship. Friendship is the ideal for<br />

intersubjective relations. Just like <strong>Herder</strong>, <strong>Kant</strong> reverses the traditional neoplatonic<br />

hierarchy to assert friendship as a higher form <strong>of</strong> ethical relation than love.<br />

Friendship, <strong>Kant</strong> insists time and again, checks and frustrates love. That is, <strong>Kant</strong>—<br />

following the neoplatonists—explicitly conceives love as a desire for union, but<br />

insists that ‘respect’ is a necessary supplement in order to limit such unity. <strong>The</strong><br />

neoplatonic ideal <strong>of</strong> two subjects fusing together in love is explicitly rejected by <strong>Kant</strong>

in favour <strong>of</strong> a more temperate balance between unity and separation which he labels<br />

‘friendship’.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are three fundamental reasons <strong>Kant</strong> prefers friendship to love. First, friendship,<br />

unlike love, is necessarily reciprocal: ‘<strong>The</strong>re can be amor unilateralis; but strictly such<br />

well-wishing changes into friendship (amicitia) through a reciprocal love, or amor<br />

bilateralis.’ (1997, 27:676) Second, friendship, unlike love, requires equality between<br />

the parties: ‘inter superiors et inferiors no friendship occurs’ (ibid, 27:676), for<br />

friendship demands ‘reciprocal esteem… among equals’ (ibid, 27:680). Finally, and<br />

here <strong>Kant</strong> is most insistent, friendship, unlike love, keeps the other at a distance. He<br />

writes in the Lectures, we ‘cannot permit the other to come too close… In this lies the<br />

mutual restriction <strong>of</strong> reciprocal love among friends.’ (ibid, 27:682) In consequence,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kant</strong>’s ‘rules <strong>of</strong> prudence’ reads, ‘To keep sufficiently at a distance from our<br />

friend’ so as to prevents ‘rash communication and… unrestrained love’, for ‘Too deep<br />

an intimacy detracts from worth’ (ibid, 27:684-5). <strong>Kant</strong> returns to this topic in the<br />

published version <strong>of</strong> the Metaphysik der Sitten. <strong>The</strong>re he writes,<br />

Love can be regarded as attraction and respect as repulsion, and if the principle <strong>of</strong><br />

love bids friends draw closer, the principle <strong>of</strong> respect requires them to stay at a<br />

proper distance from each other. This limitation on intimacy, which is expressed<br />

in the rule that even the best <strong>of</strong> friends should not make themselves too familiar<br />

with each other, contains a maxim that holds [in all cases]. (1996, 6:470)

<strong>The</strong> other must always be kept at their proper distance; pious fusion in love is to be<br />

avoided in favour <strong>of</strong> a relation <strong>of</strong> friendship in which the subject works at maintaining<br />

a barrier between her and her friends.<br />

<strong>Kant</strong> therefore stresses the artificial nature <strong>of</strong> friendship. While love ‘already lies in<br />

human nature’, friendship ‘is not a natural inclination’ but a task (1997, 27:682). Love<br />

and piety might be natural to humanity, but pudor pietatis and the restraint <strong>of</strong> love<br />

require work—they involve an unnatural, forced operation on ourselves. This, indeed,<br />

adds to their ethical value for <strong>Kant</strong>. 23 <strong>The</strong> artificiality <strong>of</strong> impiety is necessary to avoid<br />

the natural lure <strong>of</strong> the neoplatonic One. And <strong>of</strong> course the religious implications <strong>of</strong><br />

such a move must always be kept in mind: our desire for God and for apotheosis must<br />

be suppressed. Only friendship with God safeguards the requisite pudor pietatis.<br />

This aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kant</strong>’s ethics obeys a model parallel to that which guides <strong>Kant</strong>ian<br />

philosophy as a whole: we must thwart and frustrate our natural desires in order to do<br />

good philosophy. <strong>Reason</strong> may desire to illegitimately transcend the realm <strong>of</strong> possible<br />

experience, but it is the task <strong>of</strong> the philosopher to restrain such natural desires. Just as<br />

neoplatonic piety disregards the integrity <strong>of</strong> the individual, metaphysical reason<br />

‘tear[s] down all those boundary-fences and… seize[s] possession <strong>of</strong> an entirely new<br />

domain which recognises no limits <strong>of</strong> demarcation.’ (1929, A296/B352) Such<br />

unrelenting transcendence is ‘the natural predisposition <strong>of</strong> our reason’ (2001, 4:353)<br />

which the philosopher must labour tirelessly at frustrating through conceptual work.<br />

<strong>Reason</strong> must be kept dissatisfied. 24<br />

<strong>The</strong> God/human ethical relation is one more<br />

example <strong>of</strong> this same model—a pudor pietatis. Both theoretically and ethically, the<br />

human individual requires ‘discipline’— ‘a system <strong>of</strong> precautions and self-

examination… by which the constant tendency to disobey certain rules is restrained<br />

and finally extirpated.’ (1929, A709-11/B737-9) In fact, in On a Recently Prominent<br />

Tone, <strong>Kant</strong> goes so far as to speak <strong>of</strong> ‘the police in the kingdom <strong>of</strong> the sciences’ who<br />

regulate ‘the philosopher <strong>of</strong> vision’ (2002, 8:403-4).<br />

<strong>Reason</strong>’s ethical demand is to thwart the desire so natural to humanity to fuse with the<br />

deity and so put an end to individual life. God must be held ethically at the same<br />

distance that the noumenal is theoretically. Only through restraint and ‘bashfulness’<br />

can good philosophy and correct living occur. Such is <strong>Kant</strong>’s anti-Platonic ethics.<br />

[A] A Genealogy <strong>of</strong> Piety<br />

In this essay, I have brought together three ‘scenes’ from the interface <strong>of</strong> moral<br />

philosophy and philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion which all originate from late eighteenthcentury<br />

Germany and are all concerned with developing alternatives to dominant<br />

neoplatonic conceptions <strong>of</strong> self-destructive piety. <strong>The</strong>y are not identical by any<br />

means 25 , yet all three do illustrate a similar transition. In this final, concluding section,<br />

I now want to place this description within a larger theoretical framework. It is here<br />

that I finally answer the question I posed in my Introduction: why has contemporary<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion forgotten piety?<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no doubting the current hostility to <strong>Kant</strong> among analytic philosophers <strong>of</strong><br />

religion. 26 As a result, bold metaphysical truths are articulated without due attention to<br />

the philosophical conditions underlying them. Contemporary philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion<br />

names God, the afterlife and theological dogmas, but neglects that which makes such

naming possible. 27 This is not a new trend, however. Indeed, what I have implicitly<br />

argued in this essay is that such hostility to criticism (in the <strong>Kant</strong>ian sense) within<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion has a long historical tradition reaching back to the late<br />

eighteenth century. It is a tradition that features <strong>Kant</strong> himself! <strong>Kant</strong>’s philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

piety (along with <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Goethe</strong>’s) is anti-transcendental—a philosophy <strong>of</strong> piety<br />

that reverts to dogmatism in order to combat its opponents. <strong>The</strong> dogmatism <strong>of</strong> the<br />

analytic theology movement is merely the culmination <strong>of</strong> this tradition.<br />

<strong>Goethe</strong>, <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong> all attack neoplatonic piety on the grounds that it gives into<br />

its desire for God. On the contrary, they argue, this desire must be thwarted.<br />

Philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion needs to be a disinterested enterprise, exhibiting indifference to<br />

the divine. God must keep his distance. Yet, the problem with such a move is that it<br />

forecloses self-examination. Disinterest in God is disinterest in piety itself. <strong>The</strong><br />

condition on which philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion emerges as a disinterested discipline is<br />

suppressed in the very act <strong>of</strong> self-constitution. <strong>The</strong>refore, <strong>Goethe</strong>, <strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong><br />

inaugurate a form <strong>of</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion that neglects its own conditions. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

formulate a new piety <strong>of</strong> thought which prohibits any talk <strong>of</strong> piety. Philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

religion here takes on dogmatic form.<br />

I want to explore this twist further in terms drawn from Philip Goodchild’s genealogy<br />

<strong>of</strong> piety. 28 Among the many lines <strong>of</strong> thought running through Goodchild’s Capitalism<br />

and Religion, one charts piety’s disappearance from philosophical scrutiny. 29 Why has<br />

modern reason effaced its own pieties? <strong>The</strong> answer concerns the nature <strong>of</strong> these<br />

pieties. <strong>The</strong>re are two: to the question, ‘what is the appropriate way to relate to God?’,<br />

one type <strong>of</strong> piety responds: ‘God is to be approached and fused with’; while the other

esponds: ‘God must be held at a distance’. Thought must either possess God or exalt<br />

Him from afar. <strong>The</strong>se two poles exist in a dialectic which circles between yielding to<br />

the desire to fuse with God and cultivating a will which thwarts such desire. Desire<br />

must be both satisfied and unsatisfied. What is crucial is that both moments (despite<br />

their antithetical relation) have an identical result—the suppression <strong>of</strong> piety. Both<br />

pieties put paid to any further critical discussion <strong>of</strong> piety as a concept. It is here we<br />

have the reason for philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion’s silence on this issue and in consequence<br />

the reason for its incessant dogmatism.<br />

This ‘dialectic’ is <strong>of</strong> course just an abstract summary <strong>of</strong> the transitions involved in the<br />

three ‘scenes’ I have described in this essay. On the one hand, piety is a desire for<br />

God. Such is the fundamental principle <strong>of</strong> the neoplatonic piety against which <strong>Goethe</strong>,<br />

<strong>Herder</strong> and <strong>Kant</strong> were reacting. Moreover, they attacked it because it is selfdestructive:<br />

piety is itself destroyed as soon as God is obtained. It obeys the logic <strong>of</strong><br />

desire elucidated by Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium—the fulfilment <strong>of</strong> desire is<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> desire. Goodchild writes similarly,<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> piety that claims to identify its divinity, whether through ascending<br />

to heaven, or by the divinity ascending to earth, is that it abolishes the temporal<br />

existence <strong>of</strong> piety, and, with it, piety itself. (2002, p. 7)<br />

In the beatific vision, piety becomes redundant to itself. On this view, the goal <strong>of</strong><br />

philosophy is the elimination <strong>of</strong> all talk about piety, for once the desire on which<br />

philosophy is founded (fusion with God) is achieved, a critical philosophy <strong>of</strong> piety is

unnecessary. Dogmatic philosophy <strong>of</strong> religion is the end to which such philosophy<br />

strives.<br />