Fall 2007 - United States Lipizzan Federation

Fall 2007 - United States Lipizzan Federation

Fall 2007 - United States Lipizzan Federation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

By Polly DuPont<br />

Horses in Art<br />

Italian Renaissance, Ancient Rome, and Greece<br />

In this issue, I wanted to write about<br />

the type of horse, so like the <strong>Lipizzan</strong>,<br />

which we see in much of the Italian art of<br />

the Renaissance. As the article progressed,<br />

I discovered that I could not talk about<br />

the Renaissance horses without bringing<br />

in also the horses of Ancient Rome. The<br />

Italian Renaissance was based in part on<br />

the “rediscovery” of Ancient Rome and<br />

Greece, through Magna Grecia as well as<br />

through the Greek culture introduced<br />

by the Scholars from Byzantium in the<br />

1400s, Roman ruins and sculptures, friezes,<br />

triumphal arches and so forth.<br />

You will find history books saying that<br />

the Romans were not interested in horse<br />

breeding, presumably because, given the<br />

extent of the Empire, they were able to<br />

import whatever horses they wished in<br />

whatever numbers necessary. These came<br />

from the outlying countries of the empire,<br />

many of which were famous for their horse<br />

breeding peoples and tribes. The fact that<br />

loaded ships and caravans were sent to these<br />

outlying military stations, meant that they<br />

could return with goods, including horses.<br />

However, local donkeys, horses, and oxen<br />

were certainly bred in the country estates<br />

around Rome, and it seems to me highly<br />

unlikely that no one in these estates became<br />

fascinated and passionate about the noble<br />

horses that arrived from far lands, wishing<br />

to breed some for themselves...<br />

Roman art shows quite a different type<br />

of horse from those seen in earlier Persian,<br />

Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Etruscan<br />

art. (see Etruscan Winged Horses, horses in<br />

friezes at Persepolis, in frescoes in Egypt, in<br />

frescoes from wall paintings in Etruscan<br />

tombs all of which are of lighter build, more<br />

like the Arab and the Akhal Teke. A horse<br />

more like the <strong>Lipizzan</strong> is seen in the Elgin<br />

marbles frieze from pediment of the temple<br />

of Apollo on the acropolis of Athens, now in<br />

the National Gallery, London. Examples of<br />

the horse in Roman art are the Equestrian<br />

statue of Marcus Aurelias, the four bronze<br />

horses now in the Loggia of San Marco in<br />

Venice, horses in bas relief on triumphal<br />

arches (featured at right).<br />

Furthermore, the existence of horses suitable<br />

for cavalry are to be found in the legends<br />

about the ancestors of the Camargue<br />

horses and those herds in upper Italy being<br />

remnants of the passing armies of Hannibal<br />

24 - USLR News <strong>Fall</strong>, <strong>2007</strong><br />

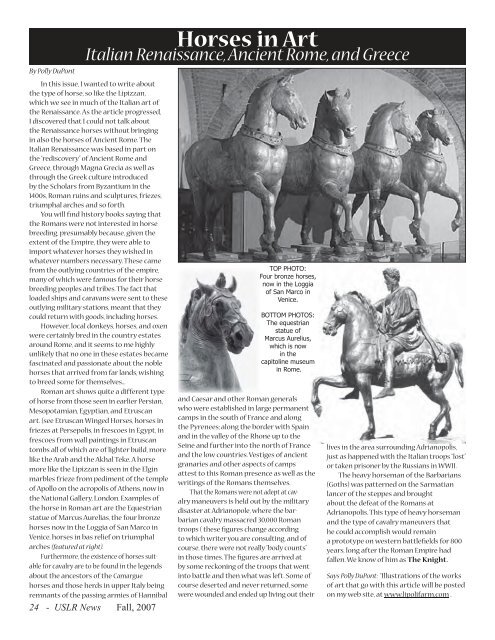

TOP PHOTO:<br />

Four bronze horses,<br />

now in the Loggia<br />

of San Marco in<br />

Venice.<br />

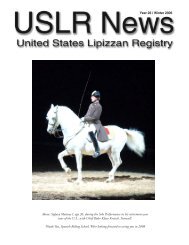

BOTTOM PHOTOS:<br />

The equestrian<br />

statue of<br />

Marcus Aurelius,<br />

which is now<br />

in the<br />

capitoline museum<br />

in Rome.<br />

and Caesar and other Roman generals<br />

who were established in large permanent<br />

camps in the south of France and along<br />

the Pyrenees; along the border with Spain<br />

and in the valley of the Rhone up to the<br />

Seine and further into the north of France<br />

and the low countries. Vestiges of ancient<br />

granaries and other aspects of camps<br />

attest to this Roman presence as well as the<br />

writings of the Romans themselves.<br />

That the Romans were not adept at cavalry<br />

maneuvers is held out by the military<br />

disaster at Adrianopole, where the barbarian<br />

cavalry massacred 30,000 Roman<br />

troops ( these figures change according<br />

to which writer you are consulting, and of<br />

course, there were not really “body counts”<br />

in those times. The figures are arrived at<br />

by some reckoning of the troops that went<br />

into battle and then what was left. Some of<br />

course deserted and never returned, some<br />

were wounded and ended up living out their<br />

lives in the area surrounding Adrianopolis,<br />

just as happened with the Italian troops “lost”<br />

or taken prisoner by the Russians in WWII.<br />

The heavy horseman of the Barbarians<br />

(Goths) was patterned on the Sarmatian<br />

lancer of the steppes and brought<br />

about the defeat of the Romans at<br />

Adrianopolis. This type of heavy horseman<br />

and the type of cavalry maneuvers that<br />

he could accomplish would remain<br />

a prototype on western battlefields for 800<br />

years, long after the Roman Empire had<br />

fallen. We know of him as The Knight.<br />

Says Polly DuPont: “Illustrations of the works<br />

of art that go with this article will be posted<br />

on my web site, at www.lipolifarm.com .