You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

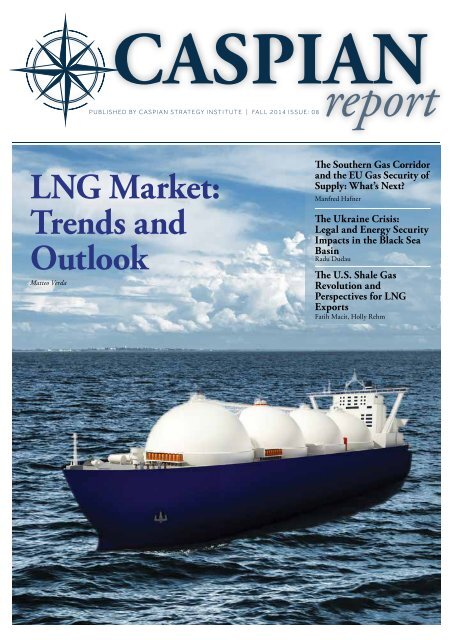

CASPIAN<br />

PUBLISHED BY CASPIAN STRATEGY INSTITUTE | FALL <strong>2014</strong> ISSUE: <strong>08</strong><br />

LNG Market:<br />

Trends and<br />

Outlook<br />

Matteo Verda<br />

The Southern Gas Corridor<br />

and the EU Gas Security of<br />

Supply: What’s Next<br />

Manfred Hafner<br />

The Ukraine Crisis:<br />

Legal and Energy Security<br />

Impacts in the Black Sea<br />

Basin<br />

Radu Dudau<br />

The U.S. Shale Gas<br />

Revolution and<br />

Perspectives for LNG<br />

Exports<br />

Fatih Macit, Holly Rehm

CASPIAN<br />

Publisher<br />

<strong>Caspian</strong> Strategy Institute<br />

Owner on Behalf of Publisher<br />

Haldun Yavaş<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Efgan Nifti<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Hande Yaşar Ünsal<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Siddharth Saxena, Gönül Tol, Bekir Günay, Efgan Nifti, Şaban Kardaş, Svante E. Cornell, Taleh Ziyadov, Amanda<br />

Paul, Mitat Çelikpala, Ayça Ergun, John Roberts, Fatih Macit, Şener Aktürk, Kornely Kakachia, Ercüment Tezcan,<br />

Vladimir Kvint, Joshua Walker, Sham L. Bathija, Emin Akhundzada, Hayreddin Aydınbaş, Ahmet Yükleyen,<br />

Mübariz Hasanov, Fatih Özbay, İbrahim Palaz, Friedbert Pflüger<br />

Researcher<br />

Seda Birol<br />

Research Assistants<br />

Ayhan Gücüyener<br />

Emin Emrah Danış<br />

Seray Özkan<br />

Translator<br />

Cansu Ertosun<br />

Graphic Design<br />

Hülya Çetinok<br />

Mailing Address<br />

Veko Giz Plaza, Maslak Meydan Sok., No:3 Kat:4 Daire:11-12 Maslak<br />

34298 Sarıyer - İstanbul - TÜRKİYE<br />

Telephone<br />

+90 212 999 66 00<br />

Fax:<br />

+90 212 999 66 01<br />

E-mail:<br />

info@hazarraporu.com - medya@hazar.org<br />

Printing-Binding<br />

Bilnet Matbaacılık Biltur Basım Yay. ve Hiz. A.Ş.<br />

Dudulu Organize Sanayi Bölgesi 1.Cadde No: 16<br />

Esenkent – Ümraniye 34476 İSTANBUL<br />

Tel: 444 44 03<br />

Publication Type<br />

Periodical<br />

The opinions expressed within are those of the authors<br />

and do not necessarily reflect HASEN policy. No part<br />

of this magazine may be reproduced in whole or in part<br />

without written permission of the publisher and the author.

Dear Readers,<br />

CASPIAN REPORT<br />

2<br />

It is my utmost pleasure to introduce the 8th issue of the <strong>Caspian</strong><br />

<strong>Report</strong>. Since our Summer issue, there have been significant geopolitical<br />

and economic developments, bringing profound challenges<br />

to the global policymaking. We have witnessed an almost<br />

40 per cent decline in oil prices, from 115 USD per barrel to 65<br />

USD due to weakening global demand; instability and the growth<br />

of the radical terror group ISIS in the Middle East; slowdown in<br />

global economic growth; and the Russia – West standoff over<br />

Ukraine. These major headlines from the past three months will<br />

of course continue to shape political and economic developments<br />

across the globe.<br />

Our current issue takes an in-depth look at some of these developments,<br />

from both the regional and global perspectives. Among<br />

the many factors behind the sharp decline in oil prices, the most<br />

influential one is the shale oil/gas revolution in the United States,<br />

which will also position the US as the world’s biggest oil/gas producer.<br />

One of our frequent contributors, Fatih Macit, has written<br />

a special analysis together with Holly Rehm, providing a unique<br />

perspective on unconventional gas production in the US and its<br />

potential impact on the global energy supply. Macit and Rehm acknowledge<br />

that the shale revolution in the US is indeed a tremendous<br />

development with huge potential to satisfy American energy<br />

demands. However, the prospects of high volume exports to European<br />

energy markets are relatively low, and are unlikely to assuage<br />

European concerns over energy security. The majority of US<br />

LNG exports are expected to go to Asian markets, which are more<br />

commercially attractive than Europe’s.<br />

Efgan NIFTI<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Twitter: @enifti<br />

efgan.niḟtiẏev@hazar.org<br />

Our cover story, written by our Italian colleague Matteo Verda,<br />

provides a timely analysis of the global context affecting potential<br />

US LNG supplies. His article examines not only LNG supplies<br />

from the US, but also the global LNG markets that are showing robust<br />

growth. His analysis reveals that the majority of the demand

EDITORIAL<br />

comes from Asian markets, where Qatar has emerged as one of<br />

the primary suppliers. One of the biggest challenges for the LNG<br />

markets is the imbalance between the export, transport and regasification<br />

capacities. LNG import terminals in some regions are<br />

underutilised; in Europe, for instance, only one-third of the capacity<br />

is used. Some countries, such as Australia, are making heavy<br />

investments in order to increase their export potential. In the long<br />

term, Australia is expected to become the largest supplier of LNG<br />

in the world.<br />

As in our previous issues, we continue to closely follow the developments<br />

concerning the European and <strong>Caspian</strong> energy markets.<br />

There are a number of significant headlines worth keeping an<br />

eye on, among them European efforts to advance with the Energy<br />

Union and the opening of the Southern Gas Corridor. Articles by<br />

Manfred Hafner, Mubariz Hasanov, Arzu Yorkan, Thanos Dokos,<br />

Nino Kalandadze and Nicolo Rossetto illuminate the key issues<br />

around these two major drivers of Europe’s energy future.<br />

The protracted crisis in Ukraine is also another geopolitical flashpoint<br />

that requires attention. Another expert, Radu Dudau from<br />

Romania, analyses the Russian – Western standoff over Ukraine in<br />

the context of the potential implications for the Black Sea region.<br />

Mesut Hakki Casin and Roman Rukomeda provide a useful perspective<br />

on the recent China - Russia natural gas deal, reached at<br />

the peak of the Ukraine crisis, which has also had a major impact<br />

on EU-Russia energy relations. Faced with energy sanctions imposed<br />

by its biggest export market, Russia needs new customers<br />

for its large natural gas supplies: a deal with China is critically<br />

important for the Putin administration.<br />

IT IS MY UTMOST<br />

PLEASURE TO GREET<br />

YOU IN CASPIAN<br />

REPORT’S 8 TH ISSUE.<br />

SINCE THE SUMMER<br />

ISSUE SIGNIFICANT<br />

GEOPOLITICAL<br />

AND ECONOMIC<br />

DEVELOPMENTS<br />

EMERGED BRINGING<br />

PROFOUND<br />

CHALLENGES TO THE<br />

GLOBAL POLICYMAKING.<br />

I wish you a pleasant read, and look forward to presenting you<br />

with our Winter 2015 issue.

CASPIAN<br />

CASPIAN REPORT<br />

4<br />

06<br />

FATIH MACIT<br />

HOLLY REHM<br />

The U.S. Shale Gas<br />

Revolution and<br />

Perspectives for LNG<br />

Exports<br />

20<br />

MANFRED HAFNER<br />

The Southern Gas<br />

Corridor and the EU Gas<br />

Security of Supply: What’s<br />

Next<br />

34<br />

MATTEO VERDA<br />

LNG Market: Trends and<br />

Outlook<br />

44<br />

MUBARIZ HASANOV<br />

An Overview of EU Energy<br />

Markets<br />

56<br />

NINO KALANDADZE<br />

The Southern Gas<br />

Corridor - Window of<br />

Opportunity or Challenge<br />

for the West<br />

68<br />

RADU DUDAU<br />

The Ukraine Crisis: Legal<br />

and Energy Security<br />

Impacts in the Black Sea<br />

Basin

TABLE OF CONTENS<br />

88<br />

MESUT HAKKI CASIN<br />

Why Russia Signed a Major<br />

Gas Contract with the<br />

Chinese Dragon: Challenge<br />

to Real Partnership or<br />

Scarce Wedding Candy<br />

114<br />

ARZU YORKAN<br />

Turkey’s Renewable Energy Policy<br />

- Towards Achieving ‘2023’ Targets<br />

“Resource Capacity, Current Situation,<br />

Shortcomings, And Remedies”<br />

128 NICOLO ROSSETTO<br />

The EU Agreement on the 2030<br />

Framework for Climate and Energy Policy<br />

102<br />

THANOS DOKOS<br />

THEODORE TSAKIRIS<br />

TAP/Southern Corridor<br />

and Greece: National and<br />

Regional Implications Gas<br />

Markets<br />

132<br />

ROMAN RUKOMEDA<br />

The Phantom of Russia-China Gas Deal

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

6<br />

THE U.S. SHALE GAS<br />

REVOLUTION AND<br />

PERSPECTIVES FOR LNG<br />

EXPORTS<br />

FATIH MACIT<br />

SENIOR FELLOW, CENTER ON ENERGY AND ECONOMY, HASEN<br />

HOLLY REHM<br />

THE PAUL H. NITZE SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL<br />

STUDIES (SAIS), JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

The aim of this report is to analyse the<br />

dynamics behind the shale gas revolution<br />

in the U.S. and to generate some<br />

perspectives on future U.S. LNG exports<br />

to European or Asia-Pacific markets.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The shale gas developments in the<br />

U.S. have revolutionised global energy<br />

markets over the past two decades.<br />

In its 2009 report, Energy Information<br />

Administration stated that the<br />

dependence of the U.S. on imported<br />

natural gas will increase over the<br />

coming decades, and prices will rise.<br />

Since 2009, things have changed significantly,<br />

and we are now talking<br />

about potential U.S. LNG exports to<br />

European and Asia-Pacific markets.<br />

Between 20<strong>08</strong> and 2013, the U.S. was<br />

able to increase its natural gas production<br />

by almost 117 billion cubic<br />

meters (bcm), but the consumption<br />

of natural gas has increased by only<br />

78 bcm. The immediate impact of this<br />

boom in natural gas production has<br />

been cost: the price per thousand cubic<br />

feet of natural gas dropped below<br />

$2 in the second quarter of 2012. At<br />

that time, the LNG spot price in Asia<br />

was around $16.5 and the average<br />

price in Germany was around $11.<br />

Even today the price per thousand<br />

cubic feet of natural gas in the U.S. is<br />

one-third of the price in Asia-Pacific<br />

markets. These numbers reveal the<br />

scale of the natural gas revolution.<br />

The aim of this report is to analyse<br />

the dynamics behind the shale gas<br />

revolution in the U.S. and to generate<br />

some perspectives on future U.S. LNG<br />

exports to European or Asia-Pacific<br />

markets. First of all, the report will<br />

provide a summary of the origins of<br />

the U.S. shale gas revolution, and discuss<br />

the domestic conditions that enabled<br />

this scenario. We will also provide<br />

a brief analysis on the economic<br />

benefits of the shale gas revolution<br />

for the U.S., particularly in relation to<br />

the economic recovery following the<br />

20<strong>08</strong> global financial crisis. Lastly, we<br />

will consider the prospects for LNG<br />

exports to Europe and Asia-Pacific,<br />

specifically whether those exports<br />

will become a game changer in these<br />

markets.<br />

THE U.S. SHALE GAS REVOLUTION<br />

In its most recent report on the gas<br />

market, the International Energy<br />

Agency (IEA) asserts that the U.S. will<br />

remain the unchallenged leader in<br />

unconventional gas development. 1<br />

The unconventional and shale gas<br />

boom in the U.S. has taken many by<br />

surprise and been a boon for the<br />

country’s oil and gas industry. The<br />

7<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

1.<br />

IEA (<strong>2014</strong>) “Medium-Term Gas Market <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2014</strong>”, Paris, France, 78.

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

8<br />

shale revolution, as it has become<br />

known, has immense potential to<br />

dramatically alter the domestic and<br />

global energy landscape. How did the<br />

shale gas revolution begin and what<br />

led to its development in the U.S.<br />

verses other areas also rich in shale<br />

resources This section will attempt<br />

to answer these questions while providing<br />

an overview of shale gas as<br />

well as its impacts on the American<br />

economy.<br />

SHALE GAS: BACKGROUND AND<br />

HISTORY IN THE U.S.<br />

Shale gas is a type of unconventional<br />

natural gas found in shale rock deposits.<br />

Other types of unconventional<br />

gas include coal bed methane, deep<br />

gas, tight gas, and methane hydrates. 2<br />

Shale gas is generally dry gas and primarily<br />

composed of methane, though<br />

some shale beds also produce wet<br />

gas. Due to the low permeability of<br />

shale, the gas trapped in these deposits<br />

is unable to migrate within the<br />

rocks, except over millions of years.<br />

This feature distinguishes shale gas<br />

from conventional gas, which is contained<br />

in sands or carbonate reservoirs<br />

where it resides in interconnected<br />

spaces that allow permeable<br />

flow throughout the reservoir and<br />

also naturally to the well during the<br />

drilling process. By contrast, unconventional<br />

gas is produced from low<br />

permeability sources such as tight<br />

sands, coal, or shale. Due to this low<br />

permeability, the reservoirs must be<br />

artificially induced to produce additional<br />

permeability and stimulate the<br />

flow of gas to the well. Shale gas wells<br />

can be similar to conventional gas<br />

wells in their production rates, depth,<br />

and drilling. 3<br />

Shale formations are found across<br />

much of the contiguous U.S. Shale gas<br />

is found in “plays,” or shale formations<br />

containing large quantities of<br />

natural gas with similar geological<br />

and geographic properties. 4 Two of<br />

the most active and important shale<br />

plays in the U.S. are the Barnett and<br />

Marcellus Shale. Other operational<br />

formations include the Haynesville,<br />

Permian, Antrim, Fayetteville, New<br />

Albany, Eagle Ford, and Bakken Shale<br />

areas. Each play has its own unique<br />

set of drilling challenges, such the<br />

depth of the formation and its location<br />

in relation to major cities or<br />

2.<br />

EIA, “What is shale gas and why is it important” http://www.eia.gov/energy_in_brief/article/<br />

about_shale_gas.cfm. Accessed June 6, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

3.<br />

U.S. Department of Energy (2009) “Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A<br />

Primer,” Oklahoma, 14-15.<br />

4.<br />

EIA, “What is shale gas and why is it important”

towns. The Barnett Shale in Texas led<br />

the way in the shale revolution, as<br />

many technological advances were<br />

discovered and tested during its development.<br />

5<br />

The Marcellus Shale is the most expansive<br />

play, encompassing six states<br />

in the north-eastern U.S., from Tennessee<br />

to New York. 6 The development<br />

of this play has seen significant<br />

strides in production, and according<br />

to the U.S. Energy Information Agency<br />

(EIA), production increased to approximately<br />

12.5 bcm per month in<br />

April <strong>2014</strong>, from 8.6 bcm per month<br />

in early 2013. Production increases<br />

have also been witnessed recently in<br />

the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Permian<br />

Shale, while production decreased in<br />

the Haynesville Shale. 7<br />

Horizontal drilling and hydraulic<br />

fracturing (commonly referred to as<br />

“fracking”) have made all of this shale<br />

gas extraction possible. Fracking involves<br />

pumping a high-pressure miture<br />

of water, sand, and chemicals to<br />

break apart the gas trapped in the<br />

shale formations. This process opens<br />

the cracks in the rock and stimulates<br />

the natural gas to flow from the<br />

cracks and into the well. Fracking,<br />

along with horizontal drilling, allows<br />

effective and economically efficient<br />

extraction of natural gas from shale<br />

THE FIRST PRODUCTIVE SHALE GAS WELLS WERE<br />

DRILLED IN NEW YORK IN 1821.<br />

formations. As the EIA has noted,<br />

without these technologies, gas<br />

would not flow freely into the wells,<br />

and commercially viable quantities<br />

of gas would not be recoverable from<br />

the shale. 8 Before the developments<br />

of these technologies, many shale<br />

reservoirs were deemed not economically<br />

viable.<br />

The first productive shale gas wells<br />

were drilled in New York in 1821.<br />

These shallow and simple wells provided<br />

small amounts of natural gas<br />

which were used mainly for lighting<br />

purposes. These early resources<br />

played a key role in bringing lighting<br />

to the homes and streets of the<br />

eastern U.S. The first field development<br />

of shale formations occurred<br />

in Ohio and Kentucky nearly one<br />

hundred years later. Hydraulic fracturing<br />

was first developed in the U.S.<br />

9<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

5<br />

U.S. Department of Energy, “Modern Shale Gas Development” 16-18.<br />

6.<br />

Ibid, 21.<br />

7.<br />

IEA, “Medium-Term Gas” 74.<br />

8.<br />

EIA, “What is shale gas and why is it important”

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

10<br />

in the 1950s. However, it was not until<br />

the 1980s that large-scale fracking<br />

and shale development began in<br />

the Barnett Shale in Texas. Horizontal<br />

drilling and fracking began to be<br />

used in tandem in the early 1990s<br />

and attracted the attention of the oil<br />

and gas sector in the U.S. From there,<br />

technological innovations and adaptations<br />

through work on the Barnett<br />

and Bakken plays have greatly improved<br />

the feasibility and effectiveness<br />

of shale gas drilling. 9<br />

While fracking has been used in the<br />

U.S. for decades, plans for widespread<br />

fracking with the shale revolution<br />

have stirred controversy. Groups<br />

have raised concerns over environmental<br />

issues, including contamination<br />

of water resources, pollution<br />

caused by mishandled and potentially<br />

hazardous hydraulic fracturing<br />

fluid, methane leakages, and seismic<br />

effects, as fracking has been shown<br />

to cause to minor earthquakes. Proponents<br />

argue that with robust regulations<br />

and monitoring, fracking can<br />

be done safely and shale gas can effectively<br />

replace more harmful fossil<br />

fuels. Natural gas emits significantly<br />

less carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide<br />

than the combustion of either<br />

coal or oil. 10 Many also argue that natural<br />

gas is a cleaner “transition fuel”<br />

as countries convert from fossil fuels<br />

to renewable energy sources.<br />

MADE IN AMERICA: DOMESTIC<br />

CONDITIONS FOR THE<br />

DEVELOPMENT OF SHALE GAS<br />

Despite other potentially large shale<br />

formations around the world, the U.S.<br />

remains the only country to have initiated<br />

the widespread development<br />

of these resources. Several arguments<br />

have been put forward to explain the<br />

success of the shale gas revolution in<br />

the U.S. Robert Blackwill and Meghan<br />

O’Sullivan sum up these arguments<br />

succinctly in their article on the shale<br />

revolution: “The fracking revolution<br />

required more than just favourable<br />

geology; it also took financiers with<br />

a tolerance for risk, a property-rights<br />

regime that let landowners claim underground<br />

resources, a network of<br />

service providers and delivery infrastructure,<br />

and an industry structure<br />

characterized by thousands of entrepreneurs<br />

rather than a single national<br />

oil company.” 11 In addition, publicprivate<br />

partnerships in research and<br />

development of shale technologies,<br />

favourable policies and regulations,<br />

established supply chains, and familiarity<br />

with oil and gas drilling have all<br />

contributed to the U.S. shale revolution<br />

and enabled the effective development<br />

of national shale resources.<br />

The unique property rights regime in<br />

America is also credited with helping<br />

spur the shale revolution. In contrast<br />

to many other countries, in the U.S.<br />

a homeowner owns their home, the<br />

land it sits on as well as the ground<br />

below and any resources contained<br />

therein. In other countries, this land<br />

would be controlled or heavily regulated<br />

by the state. Bypassing state<br />

involvement, any company able to<br />

procure an agreement with a homeowner<br />

can begin drilling on their<br />

land. This provides financial incentives<br />

for landowners to permit drilling<br />

on their land. 12 Additionally, analysts<br />

note that oil and gas drilling has<br />

taken place around the U.S. for<br />

decades, acquainting the population<br />

to drilling rigs, tankers, etc. In other<br />

areas of the world, such as Europe,<br />

the population is not familiar with<br />

these activities as most production of<br />

9.<br />

U.S. Department of Energy, “Modern Shale Gas Development” 13.<br />

10.<br />

EIA, “What is shale gas and why is it important”<br />

11.<br />

Robert D. Blackwill and Meghan L. O’Sullivan, “America’s Energy Edge: The Geopolitical<br />

Consequences of the Shale Revolution.” http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/140750/<br />

robert-d-blackwill-and-meghan-l-osullivan/americas-energy-edge. Accessed June 13, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

12.<br />

Paul Stevens (2012) “The ‘Shale Gas Revolution’: Developments and Changes,” London,<br />

England, 9.

their large energy companies occurs<br />

abroad rather than at home. 13 This<br />

has also been a determinant in the<br />

shale gas revolution.<br />

The make-up of the oil and gas sector<br />

itself has also been a factor. Since<br />

peak U.S. oil production in the 1970s,<br />

large American oil companies have<br />

focused attention on overseas and<br />

offshore oil and gas assets. The small<br />

and independent energy companies<br />

left behind were forced to innovate in<br />

order to survive. Thus, they worked<br />

to capitalize on the domestic natural<br />

resources. When companies began<br />

experimenting with horizontal drilling<br />

in sequence with hydraulic fracturing<br />

on shale plays in the 1990s,<br />

the industry began to take notice and<br />

invest in improving extraction techniques.<br />

It was this innovation and entrepreneurship<br />

- forced by necessity<br />

and competition - that catalysed the<br />

shale gas revolution. Without independent<br />

companies fighting for survival<br />

or with a single dominant energy<br />

company, the shale boom would<br />

never have taken off. 14<br />

Further, favourable domestic policies<br />

and regulations have enabled the<br />

U.S. shale boom. These include the<br />

1980s Energy Act which provides tax<br />

credits amounting to 50 cents per<br />

million British thermal unit (Btu) of<br />

gas produced, the 2005 Energy Act<br />

which specifically excludes fracking<br />

from the Environmental Protection<br />

Agency’s Clean Water Act, and the<br />

Intangible Drilling Cost Expensing<br />

Rule, which can cover more than 70<br />

percent of well start-up costs. Many<br />

other countries have stricter regulations<br />

or lack financial incentives for<br />

domestic energy companies. 15 Additionally,<br />

government involvement<br />

with the research and development<br />

of shale extraction technologies has<br />

been key. The government’s Gas<br />

Technology Institute (GTI) began<br />

research and development on what<br />

would become shale technologies in<br />

the early 1980s. GTI began a publicprivate<br />

partnership with universities,<br />

national laboratories, service providers,<br />

and federal agencies, as well as<br />

companies from the oil and gas sector<br />

with the aim of developing and<br />

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT WITH THE RESEARCH AND<br />

DEVELOPMENT OF SHALE EXTRACTION TECHNOLOGIES<br />

HAS BEEN KEY.<br />

testing technologies. With its heavy<br />

industry presence, which proved to<br />

be vital to the success of the project,<br />

this partnership was different than<br />

others. Additionally, GTI widely disseminated<br />

its findings to the industry,<br />

thus directly providing the technological<br />

know-how to the domestic<br />

companies working in the field. 16<br />

ENERGY ECONOMY: INVESTMENT<br />

IN U.S. SHALE GAS AND ITS<br />

CONTRIBUTION TO ECONOMIC<br />

RECOVERY<br />

Large investments have been made<br />

in the shale revolution; at the same<br />

time the resource boom is credited<br />

with helping the American economy<br />

recover after the 20<strong>08</strong> financial crisis.<br />

Investment in shale plays totalled<br />

$133.7 billion in the U.S. between<br />

20<strong>08</strong> and 2012. Joint ventures with<br />

foreign companies comprised 20<br />

percent of these investments, includ-<br />

11<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

13.<br />

Paul Stevens (2012) “The ‘Shale Gas Revolution’: Hype and Reality,” London, England, 13.<br />

14.<br />

Robert A. Hefner III “The United States Gas: Why the Shale Revolution Could Have Happened<br />

Only in America,” http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/141203/robert-a-hefner-iii/theunited-states-of-gas.<br />

Accessed June 13, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

15.<br />

Stevens, “The ‘Shale Gas Revolution’: Developments and Changes,” 9.<br />

16.<br />

Pipeline and Gas Journal (2013) “Unlocking the Potential of Unconventional Gas,” Houston,<br />

Texas, 26-28.

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

12<br />

SINCE THE START OF THE SHALE REVOLUTION, 150,000<br />

HORIZONTAL WELLS HAVE BEEN DUG AT A COST OF<br />

APPROXIMATELY $1 TRILLION.<br />

ing companies such as China’s Sinopec,<br />

France’s Total, and Norway’s<br />

Statoil. 17 Since the start of the shale<br />

revolution, 150,000 horizontal wells<br />

have been dug at a cost of approximately<br />

$1 trillion. 18 Each shale well<br />

costs between $3 and $12 million<br />

to drill. 19 Top overseas companies—<br />

such as Japan’s Mitsubishi Corp and<br />

Mitsui & Co— continue to invest in<br />

shale oil and gas in the U.S., despite<br />

major write-downs of more than<br />

$600 million as a result of low gas<br />

prices and reduced reserve estimates<br />

over the past two years. 20 However,<br />

there continue to be positive incentives<br />

for foreign companies to invest<br />

in shale energy, including operating<br />

in a stable country with low political<br />

and legal risks, and gaining knowledge<br />

of fracking and horizontal drilling<br />

which could be useful in development<br />

of domestic shale reserves. 21<br />

A report by IHS Global Insight estimates<br />

that more than $5.1 trillion in<br />

capital expenditures will be spent in<br />

the U.S. unconventional oil and gas<br />

industry between 2012 and 2035,<br />

with around $3.0 trillion of that spent<br />

specifically on unconventional natural<br />

gas activity. The report further<br />

notes that employment in the unconventional<br />

oil and gas sector supported<br />

1.7 million jobs in 2012, projected<br />

to double, reaching 3.5 million jobs in<br />

2035. Finally, in 2012, the unconventional<br />

gas and oil industry accounted<br />

for nearly $62 billion in federal, state,<br />

and local taxes. IHS projects that<br />

shale oil and gas activities will cumulatively<br />

generate more than $2.5 trillion<br />

in tax revenue between 2012 and<br />

2035. 22<br />

Moreover, additional supplies of domestic<br />

natural gas have put downward<br />

pressure on prices in the U.S.,<br />

saving the country billions in energy<br />

expenditures. The U.S. price of gas<br />

dropped close to $2 per million Btu<br />

in 2012, but has since risen—thanks<br />

to an extremely cold winter—and is<br />

now fluctuating around $4-$5 per<br />

million Btu. This is still nearly 3 times<br />

lower than the price in Europe and almost<br />

five times lower than in Asia. 23<br />

Lower gas prices have saved the U.S.<br />

approximately $300 billion annually<br />

in comparison with consumers in Europe<br />

and Asia. 24<br />

Further, cheap gas and a rise in natural<br />

gas liquid production has led to<br />

boom in manufacturing, specifically<br />

in the chemical and petrochemical industry.<br />

An increase in unconventional<br />

oil and gas drilling has also led to a<br />

rise in the production of natural gas<br />

liquids (NGLs), which include ethane,<br />

propane, butanes, and light naphtha.<br />

17.<br />

EIA, “Foreign investors play large role in U.S. shale industry,” http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/<br />

detail.cfmid=10711. Accessed June 17, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

18.<br />

Hefner, “The United States Gas.”<br />

19.<br />

IHS Global Insight (2012) “America’s New Energy Future: The Unconventional Oil and Gas<br />

Revolution and the US Economy,” 19.<br />

20.<br />

James Topham, “Japan trading houses keep faith in U.S. shale despite writedowns,” http://www.<br />

reuters.com/article/<strong>2014</strong>/05/<strong>08</strong>/japan-trading-house-shale-idUSL3N0NO0J8<strong>2014</strong>05<strong>08</strong>.<br />

Accessed June 17, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

21.<br />

EIA, “Foreign investors play large role.”<br />

22.<br />

IHS Global Insight, “America’s New Energy Future,” 2.<br />

23.<br />

BP, “BP Statistical Review of World Energy June <strong>2014</strong>,” http://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/<br />

pdf/Energy-economics/statistical-review-<strong>2014</strong>/BP-statistical-review-of-world-energy-<strong>2014</strong>-<br />

full-report.pdf. Accessed June 20, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

24.<br />

Hefner, “The United States Gas.”

13<br />

Shale plays with wet gas also hold a<br />

significant amount of NGLs. NGLs are<br />

used as a feedstock for petrochemical<br />

industries and also serve as a<br />

primary input in many goods. From<br />

20<strong>08</strong> to 2012, NGL production in the<br />

U.S. rose by 29 percent, largely attributable<br />

to the rise in unconventional<br />

oil and gas activities. 25 Analysts have<br />

calculated that the shale revolution<br />

has added one percentage point to<br />

the overall U.S. GDP. 26<br />

The oil and gas sector also stimulated<br />

urgently needed job creation in<br />

the wake of the financial crisis and<br />

recession. Between 2010 and 2012,<br />

the oil and gas sector added 169,000<br />

jobs nationwide, a growth rate about<br />

ten times that of overall employment<br />

growth in the U.S. States with large<br />

CHEAP GAS AND A RISE IN NATURAL GAS<br />

LIQUID PRODUCTION HAS LED TO BOOM<br />

IN MANUFACTURING, SPECIFICALLY IN THE<br />

CHEMICAL AND PETROCHEMICAL INDUSTRY.<br />

shale deposits saw hiring growth in<br />

the first decade after 2000, including<br />

Louisiana, North Dakota, Oklahoma,<br />

Texas, West Virginia, and Wyoming.<br />

Texas and North Dakota in particular<br />

saw significant increases in employment<br />

as they increased production of<br />

shale resources. Between 2006 and<br />

2012, employment in North Dakota<br />

grew by 3.4 percent and in Texas by<br />

1.5 percent, while average nationwide<br />

employment declined by 0.05<br />

percent per year. The job growth in<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

25.<br />

IHS Global Insight, “America’s New Energy Future,” 6.<br />

26.<br />

Hefner, “The United States Gas.”

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

14<br />

these two states was the fastest in<br />

the country during this period. 27<br />

The economic effects of the shale oil<br />

and gas boom have been especially<br />

striking in North Dakota. In 2002,<br />

North Dakota had the second smallest<br />

economy in the country with<br />

economic output of just $24.7 billion<br />

a year. In the ten years since, North<br />

Dakota has doubled its economy to<br />

$49.4 billion a year. This massive increase<br />

in economic output was driven<br />

primarily by the oil and gas boom<br />

in the Bakken shale play. 28 The state’s<br />

GDP growth of 9.7 percent was the<br />

country’s fastest in 2013, while its<br />

unemployment rate of 2.9 percent<br />

was the lowest nationally. North Dakota’s<br />

one-year population growth<br />

of 3.1 percent is also the highest in<br />

the country, as people flock to the<br />

state to fill the jobs mainly created<br />

by the oil and gas sector. In fact, the<br />

economic growth of the five fastest<br />

growing states in 2013—including<br />

Wyoming, Oklahoma, and West Virginia—was<br />

primarily the result of oil,<br />

gas, and coal production. 29<br />

Though shale gas production actually<br />

fell in 2013, most experts predict that<br />

U.S. shale production will continue to<br />

grow in the future. The IEA estimates<br />

natural gas output in the U.S. will increase<br />

from an estimated 650 bcm<br />

in 2011 to 840 bcm in 2035. This<br />

projection puts the U.S. ahead of Russia<br />

as the largest gas producer, and<br />

ahead of Saudi Arabia as the largest<br />

hydrocarbon producer in the world. 30<br />

This increase is due almost exclusively<br />

to shale gas sources. The EIA estimates<br />

that shale gas production will<br />

grow from 7.8 trillion cubic feet (tcf)<br />

in 2011 to 16.7 tcf in 2040. The EIA<br />

also projects that the share of shale<br />

gas in total U.S. gas production will<br />

increase from 40 percent in 2012 to<br />

53 percent in 2040. 31 By comparison,<br />

27.<br />

Stephen P.A. Brown and Mine K. Yücel (2013), “The Shale Gas and Tight Oil Boom: U.S. States’<br />

Economic Gains and Vulnerabilities,” New York, New York, 2-3.<br />

28.<br />

Blake Ellis, “How North Dakota’s economy doubled in 11 years,” http://money.cnn.<br />

com/<strong>2014</strong>/06/11/news/economy/north-dakota-economy/. Accessed June 17, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

29.<br />

Alexander E.M. Hess and Thomas C. Frohlich, “10 states with the fastest growing economies,”<br />

http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/<strong>2014</strong>/06/14/states-fastest-growingeconomies-new/10377735/.<br />

Accessed June 17, <strong>2014</strong>.<br />

30.<br />

IEA (2013), “World Energy Outlook 2013,” Paris, France, 1<strong>08</strong>-109.<br />

31.<br />

EIA (<strong>2014</strong>), “Annual Energy Outlook <strong>2014</strong>,” Washington, DC, MT-23.

shale gas provided only 1 percent of<br />

the country’s natural gas supply in<br />

2000. 32<br />

POTENTIAL LNG EXPORT<br />

TERMINALS AND CAPACITY<br />

As the shale boom drives the U.S.<br />

ahead of Russia as the largest producer<br />

of natural gas, exports of shale<br />

gas in the form of liquid natural gas<br />

(LNG) are widely anticipated. The<br />

cooling of natural gas to produce LNG<br />

is a more expensive process but allows<br />

natural gas to be shipped rather<br />

than transported via pipeline. The<br />

trade of LNG has expanded rapidly in<br />

the past decade and now accounts for<br />

a tenth of all gas produced. 33<br />

Before the shale gas revolution, the<br />

U.S. was building facilities to import<br />

natural gas. Companies are now in<br />

the processing of turning these facilities<br />

into export terminals. Around a<br />

dozen LNG terminals have been proposed<br />

by companies to the Department<br />

of Energy (DOE) and Federal Energy<br />

Regulatory Commission (FERC),<br />

the federal agencies responsible for<br />

approving export licenses and reviewing<br />

environmental impacts for<br />

each facility. If the government were<br />

to approve all the proposed facilities,<br />

the LNG export capacity (39.31 bcf/<br />

day or 400 bcm/year) would reach<br />

more than half of U.S. gas production<br />

(69.3 bcf/day as of April <strong>2014</strong>). 34-35<br />

However, many of these projects are<br />

unlikely to come to fruition.<br />

As of July <strong>2014</strong>, the DOE has awarded<br />

eight export licenses for countries<br />

that do not have free trade agreements<br />

(FTAs) with the U.S. 36 The<br />

proposed non-FTA export capacity of<br />

these eight facilities is approximately<br />

10.5 bcf/day. 37 Of the eight, only three<br />

have received the final approvals<br />

necessary from both DOE and FERC<br />

to move forward, including Cheniere<br />

Energy’s Sabine Pass, Sempra Energy’s<br />

Cameron LNG, and Freeport<br />

LNG. Sabine Pass will have an LNG<br />

export capacity of 2.2 bcf/day and<br />

is on track to begin LNG exports in<br />

late 2015 or early 2016. 38 Cameron<br />

15<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

32.<br />

Stevens, “The ‘Shale Gas Revolution’: Hype and Reality,” 14.<br />

33.<br />

Dreyer, Iana and Gerald Stang. 2013. “The shale gas ‘revolution’: Challenges and implications<br />

for the EU.” EUISS Brief 11. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies.<br />

34.<br />

U.S. Department of Energy. <strong>2014</strong>. Applications Received by DOE/FE to Export. http://energy.<br />

gov/sites/prod/files/<strong>2014</strong>/07/f18/Summary%20of%20LNG%20Export%20Applications.pdf<br />

(accessed August 5, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

35.<br />

U.S. Energy Information Agency. <strong>2014</strong>. Natural Gas Monthly. (06/30). http://www.eia.gov/<br />

naturalgas/monthly/ (accessed July 15, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

36.<br />

Platts. <strong>2014</strong>. US DOE conditionally authorizes Oregon LNG to export to non-FTA countries.<br />

(07/31) http://www.platts.com/latest-news/shipping/washington/us-doe-conditionallyauthorizes-oregon-lng-to-21001860<br />

(accessed August 5, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

37.<br />

U.S. Department of Energy, Applications Received by DOE/FE to Export.<br />

38.<br />

Cheniere Energy. 2013. Sabine Liquefaction Project Schedule. http://www.cheniere.com/<br />

sabine_liquefaction/project_schedule.shtml (accessed July 15, <strong>2014</strong>).

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

16<br />

LNG’s export capacity will be 1.7 bcf/<br />

day and construction is slated to begin<br />

this year with full operations expected<br />

by 2019. 39 Freeport LNG, the<br />

most recently approved, plans to begin<br />

construction in <strong>2014</strong> and achieve<br />

commercial operations in 2018, exporting<br />

approximately 1.8 bcf/day. 40<br />

The U.S. is also in the process of<br />

changing its policy of awarding export<br />

contracts; now only rewarding<br />

licenses to companies that have<br />

already complied with all relevant<br />

environmental regulations. The new<br />

regulations will force companies<br />

seeking to build LNG terminals to win<br />

FERC approval—a longer process<br />

costing upwards of $100 million—<br />

before they can receive approval for<br />

an export license from the DOE. Industry<br />

experts do not expect this to<br />

slow down the licensing process, but<br />

rather reward those companies with<br />

commercially-viable, well-financed,<br />

and more developed projects. 41<br />

At the same time, the House of Representatives<br />

had recently passed legislation<br />

which would set a deadline<br />

for the Department of Energy to approve<br />

licenses for LNG applications.<br />

The legislation “would require the<br />

department [DOE] to issue a decision<br />

30 days after the Federal Energy<br />

Regulatory Commission has completed<br />

its environmental analysis of<br />

an LNG export project.” 42 The bill was<br />

drafted by lawmakers frustrated by<br />

the slow pace of DOE approvals, and<br />

hoping to expedite the first U.S. LNG<br />

exports. The legislation will now be<br />

sent to the Senate for a vote. 43 Further,<br />

lawmakers have introduced the<br />

North Atlantic Energy Security Act in<br />

the Senate, aimed at reducing the red<br />

tape for U.S. companies to produce<br />

and export natural gas to the America’s<br />

allies abroad. In a joint editorial<br />

in the Wall Street Journal, two of the<br />

bill’s sponsors, Senators John Hoeven<br />

(R-ND) and John McCain (R-AZ),<br />

outlined the goal of the bill: “Today,<br />

the U.S. has the leverage to liberate<br />

our allies from Russia’s stranglehold<br />

on the European natural-gas market…<br />

We need to use our leverage wisely:<br />

to boost our economy at home and<br />

to strengthen our national security<br />

by helping our allies resist Russian<br />

aggression.” 44<br />

PERSPECTIVES ON FUTURE LNG<br />

EXPORTS<br />

In this section of the report, we will<br />

analyse the potential for U.S. LNG exports<br />

to European and Asia-Pacific<br />

markets, considering whether these<br />

exports will change the market dynamics<br />

in these regions. The current<br />

LNG terminal projects and their capacities<br />

reveal that LNG exports to<br />

Europe or Asia might begin in late<br />

2015, but not in volumes that will<br />

change the market conditions. Sabine<br />

Pass terminal is supposed to be the<br />

first to launch LNG exports, and its<br />

annual capacity is approximately<br />

22 bcm. While we believe that there<br />

39.<br />

Sempra Energy. <strong>2014</strong>. Cameron LNG: Expansion Update. http://cameronlng.com/expansionupdate.html<br />

(accessed July 14, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

40.<br />

Freeport LNG. <strong>2014</strong>. Project Status and Schedule. http://www.freeportlng.com/Project_<br />

Status.asp (accessed August 5, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

41.<br />

Crooks, Ed. <strong>2014</strong>. “US shakes up LNG export rules,” Financial Times. (05/30). http://www.<br />

ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/bff2c2d8-e799-11e3-88be-00144feabdc0.html#axzz37WGpCTlk<br />

(accessed July 14, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

42.<br />

Rascoe, Ayesha. <strong>2014</strong>. “U.S. House passes bill speeding up decisions on LNG export<br />

requests.” Reuters. (06/26). http://in.reuters.com/article/<strong>2014</strong>/06/25/usa-lng-exportsidINL2N0P6230<strong>2014</strong>0625<br />

(accessed July 10, <strong>2014</strong>).<br />

43.<br />

Ibid.<br />

44.<br />

Hoeven, John and John McCain. <strong>2014</strong>. “Putting America’s Energy Leverage to Use,” Wall<br />

Street Journal. (07/28) http://online.wsj.com/articles/john-hoeven-and-john-mccain-puttingamericas-energy-leverage-to-use-1406590261<br />

(accessed August 5, <strong>2014</strong>).

might be other terminals that can<br />

begin LNG exports, our argument is<br />

that the U.S. LNG exports will not be<br />

sufficient to fundamentally change<br />

European or Asia-Pacific markets, for<br />

various reasons.<br />

First of all, price dynamics both in<br />

U.S. markets and export markets will<br />

constrain LNG trade. The estimated<br />

cost of liquefying and shipping a<br />

thousand cubic feet of natural gas<br />

from U.S. to European markets is approximately<br />

$4, and this rises to $6<br />

when selling to Asian markets. One<br />

should also take into account the<br />

fixed costs involved in this process. It<br />

costs about $4 billion to build a liquefaction<br />

plant with a daily export capacity<br />

of one billion cubic feet. There<br />

are also important sunk costs related<br />

to obtaining necessary approvals for<br />

LNG export. For LNG trade between<br />

the United States and these markets<br />

to be viable, there should be a reasonable<br />

price difference. Although<br />

the spot LNG price in Asia declined<br />

by almost 40% in the first half of<br />

<strong>2014</strong>, there is still a $7 difference between<br />

the LNG price in United States<br />

and the price in Asia-Pacific markets.<br />

In 2013, the difference was much<br />

more marked. The average LNG price<br />

in Asia for 2013 was $16.3 compared<br />

with $3.7 in the U.S. Though the price<br />

difference between the United States<br />

and Europe is smaller in comparison,<br />

there was still a price difference<br />

of approximately $7 between these<br />

two markets in 2013. Therefore,<br />

there seems to be a profit opportunity<br />

in terms of exporting LNG to<br />

Asia. However, supply and demand<br />

pressures may rapidly eliminate<br />

this profit opportunity if the export<br />

volumes reach high levels. Energy<br />

Information Administration (2012)<br />

estimates that every billion cubic<br />

feet a day of exports might lead to<br />

a 10 to 20 cent increase in the price<br />

of per thousand cubic feet of natural<br />

gas. Thus if U.S. LNG exports either to<br />

European or Asian markets reach to<br />

LARGE LNG EXPORTS BY UNITED STATES TO<br />

EUROPEAN OR ASIAN MARKETS MAY PUT A<br />

SIGNIFICANT DOWNWARD PRESSURE ON<br />

GAS PRICES IN THESE MARKETS.<br />

100 bcm per year, the domestic price<br />

may go above $6. This price increase<br />

will happen for two reasons. Firstly,<br />

export of natural gas will limit the<br />

supply to the domestic markets, and<br />

this will immediately be reflected in<br />

a price increase. Secondly, some of<br />

the export capacity will come from<br />

new production, and the development<br />

of new gas production fields<br />

requires higher gas prices to allow<br />

the development of fields that were<br />

previously not profitable due to low<br />

gas prices. To sum up, high levels of<br />

LNG export will lead to an increase<br />

in domestic prices, and will reduce<br />

the price difference. The second aspect<br />

is related to the price dynamics<br />

in the export markets. Large LNG exports<br />

by United States to European or<br />

Asian markets may put a significant<br />

downward pressure on gas prices in<br />

these markets. This will narrow the<br />

price difference between these markets<br />

and again eliminate profit opportunities<br />

for LNG exporters. Thus<br />

market dynamics will put a downward<br />

pressure on price difference on<br />

both sides, and may thereby inhibit<br />

the growth of LNG exports.<br />

The second key barrier to high volumes<br />

of U.S. LNG exports to European<br />

and Asian markets is increased<br />

pipeline trade in natural gas trade.<br />

We will assess this separately for Europe<br />

and Asia. Europe is already the<br />

largest consumer and importer of<br />

natural gas in the world, and obtains<br />

the majority of its natural gas imports<br />

via pipelines from Russia. The<br />

region gets some LNG from Qatar, Algeria,<br />

and Nigeria, but the total LNG<br />

imports only amounts to 10% of total<br />

consumption. Europe’s LNG capacity<br />

is massively under-utilised due to<br />

high prices observed in Asian mar-<br />

17<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong>

FATIH MACIT, HOLLY REHM<br />

18<br />

kets, particularly after the Fukushima<br />

nuclear plant accident. The European<br />

Union has been trying to reduce<br />

dependence on Russian gas, and tensions<br />

in Ukraine have increased the<br />

urgency of this issue. In this respect,<br />

more LNG exports, potentially from<br />

United States as well, could provide<br />

a remedy. However, recent developments<br />

show that pipeline trade will<br />

continue to play a major role in European<br />

markets and will increase the<br />

competition for U.S. LNG. The Southern<br />

Gas Corridor project, proposed<br />

in 1990s, is now becoming a reality<br />

with the development of Trans Anatolian<br />

Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP)<br />

project between Turkey and Azerbaijan.<br />

The first gas flows to European<br />

markets through TANAP will happen<br />

by the end of 2018, at 10 bcm a year.<br />

By the mid-2020s the amount going<br />

to Europe will increase to 20 bcm.<br />

One could argue that compared to<br />

the Europe’s total natural gas consumption,<br />

this amount is fairly negligible,<br />

and will not play a major role in<br />

European natural gas markets. However,<br />

we should think this 20 bcm as<br />

an initial step in the development<br />

of the Southern Gas Corridor. At the<br />

first stage this corridor will be supported<br />

by Azerbaijani gas, but there<br />

are hopes that it will be fed by additional<br />

sources in the future. Turkmen<br />

gas, Iraqi gas and resources in East<br />

Mediterranean may find their place<br />

in this route, and ten years on, more<br />

than 60 bcm of natural gas could be<br />

transported to European markets via<br />

this pipeline. This additional gas may<br />

increase the competition in the market<br />

and reduce the need for U.S. LNG.<br />

Another important issue relates to<br />

the nature of the natural gas business<br />

in Europe. The North American<br />

natural gas business model is mostly<br />

based on a spot market. By contrast,<br />

European markets are mainly based<br />

on long-term contracts where the<br />

natural gas price is indexed to oil<br />

prices. In a spot market model there<br />

might be large fluctuations in prices<br />

for various reasons; this generates<br />

significant uncertainty, particularly<br />

for the manufacturing industry.<br />

Therefore, European producers<br />

might choose to go with current longterm<br />

contracts that reduce this price<br />

uncertainty instead of opting for LNG<br />

exports from the United States.<br />

Increased pipeline trade may also reduce<br />

the competitiveness of U.S. LNG<br />

exports to Asian markets. In contrast<br />

to European countries, countries in<br />

the Asia-Pacific region are largely<br />

reliant on LNG for their domestic<br />

natural gas demand. For some big<br />

consumers in the region like Japan<br />

and South Korea, LNG is the only<br />

source by which natural gas demand<br />

is met. These countries may remain<br />

major LNG consumers, but other big<br />

consumers are taking initiatives to<br />

increase the consumption of pipeline<br />

gas. China has recently signed<br />

an agreement with Russia that that<br />

involves the purchase of 38 bcm of<br />

natural gas annually. China is already<br />

importing a significant amount of gas<br />

from Turkmenistan via pipeline and<br />

is planning to increase this. Other important<br />

consumers in the region like<br />

India and Pakistan are also working<br />

on pipeline projects that will increase<br />

the gas supply from Turkmenistan.<br />

All these developments indicate that<br />

pipeline trade will play a greater role<br />

in Asian markets. This may in turn<br />

put a downward pressure on LNG<br />

prices and reduce the competitiveness<br />

of large scale U.S. LNG export.<br />

The third barrier to large-scale U.S.<br />

LNG export is related to developments<br />

around renewables and energy<br />

efficiency. This has been an important<br />

issue for Europe in particular<br />

over the last decade. The EU’s natural<br />

gas consumption has remained<br />

almost flat over the last ten years.<br />

The rising share of renewables in total<br />

primary energy consumption and<br />

improvements in energy efficiency

have played an important role in<br />

generating this pattern. In 2002, the<br />

share of renewables in total primary<br />

energy consumption was around 1%,<br />

and ten years on, this number stood<br />

at 6%. For 27 EU member states, energy<br />

intensity (calculated by dividing<br />

gross inland consumption of energy<br />

by GDP) was as high as 176.5 by the<br />

beginning of 2000; by the end of 2012<br />

it had declined to 143.2. This dramatic<br />

change demonstrates that one unit<br />

of GDP can now be produced using<br />

almost 20% less energy. These developments<br />

in energy efficiency and in<br />

the use of renewables may continue<br />

to put downward pressure on natural<br />

gas demand, and may reduce the<br />

attractiveness of U.S. LNG exports for<br />

European markets. The same developments<br />

may also be a problem for<br />

Asian markets. China is investing<br />

in renewable energy consumption;<br />

from 2012 to 2013 alone, the share<br />

of renewable energy in total primary<br />

energy consumption increased from<br />

1.2% to 1.5%. The average use of renewables<br />

in the Asia-Pacific region<br />

is around 1.5%. Given the European<br />

equivalent, this region still has a long<br />

way to go in this regard. Therefore,<br />

these developments may reduce the<br />

growth rate for natural gas demand,<br />

potentially reducing the price difference<br />

between these markets and<br />

United States.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

No one can deny that U.S. shale gas<br />

revolution has been one of the most<br />

important developments in global<br />

energy markets over the last two<br />

decades. Although there are other<br />

countries in the world with rich shale<br />

gas resources, domestic conditions,<br />

such as the property rights regime<br />

and make-up of the oil and gas sector,<br />

have enabled this revolution to<br />

happen in the United States. Large investments<br />

in this sector have played<br />

a significant role in helping the U.S.<br />

economy to recover from the recession,<br />

and this revolution has been a<br />

boon for the manufacturing industry<br />

in terms of significantly lowering energy<br />

costs.<br />

With the United States as a major<br />

natural gas producer, the current<br />

debate is whether we will see largescale<br />

LNG exports from U.S. to European<br />

and Asia Pacific markets. The<br />

LNG terminal projects in the United<br />

States indicate that there might be<br />

some LNG exports from United States<br />

to European or Asian markets by late<br />

2015, at volumes up to 20 bcm a year.<br />

There are strong arguments stating<br />

that U.S. LNG exports will not fundamentally<br />

change these markets. In<br />

case of large-scale LNG trade, supply<br />

and demand pressures may reduce<br />

the price difference between these<br />

markets, and transporting LNG from<br />

United States to Europe or Asia may<br />

no longer be profitable. Increased<br />

pipeline trade, improvements in energy<br />

efficiency, and increased use of<br />

renewables could be other factors<br />

that may limit the competitiveness of<br />

U.S. LNG exports.<br />

19<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong>

MANFRED HAFNER<br />

20<br />

THE SOUTHERN GAS<br />

CORRIDOR AND THE EU<br />

GAS SECURITY OF SUPPLY:<br />

WHAT’S NEXT<br />

MANFRED HAFNER<br />

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SAIS-EUROPE AND SCIENCES-PO<br />

PARIS SIMONE TAGLIAPIETRA

Because of the decreasing trend of the<br />

EU domestic gas production, the EU gas<br />

import requirements have increased<br />

rapidly over the last decade.<br />

THE GENESIS OF THE SOUTHERN<br />

GAS CORRIDOR<br />

Gas is an essential component of the<br />

energy mix of the European Union<br />

(EU), constituting one quarter of primary<br />

energy supply and contributing<br />

mainly to electricity generation,<br />

heating, feedstock for industry and<br />

fuel for transportation.<br />

Because of the decreasing trend<br />

of the EU domestic gas production<br />

(particularly due the United Kingdom),<br />

the EU gas import requirements<br />

have increased rapidly over<br />

the last decade, leading to higher<br />

levels of import dependence and<br />

ultimately outlying the need to address<br />

the issue of security of gas supply<br />

at the EU level.<br />

This need unexpectedly became<br />

tangible in January 2006, when after<br />

a long-lasting disagreement on<br />

gas prices, Russia cut off supplies to<br />

Ukraine for 3 days, Ukraine diverted<br />

volumes destined to Europe, and as a<br />

consequence gas supply to some Central<br />

European countries fell briefly. 1<br />

As a response to the energy security<br />

concerns emerged after this Russian-Ukrainian-European<br />

gas crisis,<br />

the European Commission (EC)<br />

launched in 20<strong>08</strong> a double strategy,<br />

aimed at enhancing the EU gas security<br />

of supply architecture. On<br />

the one hand, the EC targeted to enhance<br />

the EU internal energy market<br />

in order to foster gas flows between<br />

EU Member States. On the other<br />

hand, it aimed at enhancing gas<br />

sources diversification, including<br />

building LNG receiving terminals in<br />

Central and South-East Europe and<br />

pursuing the 4 th corridor (generally<br />

known as Southern Gas Corridor) in<br />

order to bring gas from <strong>Caspian</strong> and<br />

Middle Eastern producing countries<br />

to the EU.<br />

The implementation of this strategy<br />

-and particularly of the Southern<br />

Gas Corridor- was accelerated after<br />

another major natural gas crisis between<br />

Russia and Ukraine occurred<br />

in January 2009. In fact, this crisis resulted<br />

to be even worse than the previous<br />

one, as the transit of Russian<br />

gas through Ukraine was completely<br />

cut for two weeks, which resulted in<br />

21<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

1.<br />

As Pirani, Stern and Yafimava underline natural gas conflicts between Russia and Ukraine go back to the immediate aftermath of the<br />

independence of the two countries. Regular transit conflicts emerged as transit usually became a part of the price dispute on the<br />

Russian gas price for the Ukrainian domestic market. In fact, no separation between the transit gas network and the domestic gas<br />

network exists in Ukraine and Ukrainian customers usually served themselves from the transit volumes which Russia called theft of<br />

gas through the transit system. See: Pirani, S., Stern, J. and Yafimava, K. (2009), The Russo-Ukrainian Gas Dispute of January 2009:<br />

A Comprehensive Assessment, OIES paper: NG27, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

MANFRED HAFNER<br />

22<br />

THE DOCUMENT RECOGNIZED IN THE SOUTHERN<br />

GAS CORRIDOR ONE OF THE EU’S HIGHEST ENERGY<br />

SECURITY PRIORITIES.<br />

humanitarian crises in several Central<br />

and Eastern European countries<br />

that were strongly dependent on<br />

Russian gas supplies across Ukraine.<br />

This dispute has resulted in longterm<br />

economic consequences and<br />

affected the reputation of Russia as<br />

a reliable supplier and of Ukraine as<br />

a reliable transit country.<br />

The official document on which the<br />

Southern Gas Corridor is rooted<br />

is thus represented by the Communication<br />

delivered in 20<strong>08</strong> by<br />

the EC: the “Second Strategic Energy<br />

Review – An EU Energy Security<br />

and Solidarity Action Plan.” 2<br />

The document recognized in the<br />

Southern Gas Corridor one of the<br />

EU’s highest energy security priorities,<br />

outlying the need of a joint<br />

work between the EC, EU Member<br />

States and the countries concerned<br />

(Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, Iraq<br />

and Mashreq countries) with the objective<br />

of rapidly securing firm commitments<br />

for the supply of natural<br />

gas and the construction of the pipelines<br />

necessary for all stages of its<br />

development. Uzbekistan and Iran<br />

were also mentioned in the Communication<br />

as potential partners, albeit<br />

only in a long-term scenario.<br />

After the release of this document,<br />

the EC invited representatives of the<br />

countries concerned to a Ministerial<br />

level meeting aimed at securing<br />

concrete progress of the initiative<br />

in May 2009. The summit, held in<br />

Prague and named “Southern Corridor<br />

- New Silk Road”, served to<br />

express the political support to the<br />

realization of the Southern Gas Corridor<br />

as an important and mutually<br />

beneficial initiative, aimed at promoting<br />

the common prosperity, stability<br />

and security of all countries involved.<br />

The countries participating<br />

at the summit declared to consider<br />

the Southern Gas Corridor concept<br />

as a modern Silk Road interconnecting<br />

countries and people from different<br />

regions and establishing the<br />

adequate framework, necessary for<br />

encouraging trade, multidirectional<br />

exchange of know-how, technologies<br />

and experience.<br />

Furthermore, the countries participating<br />

at the summit also agreed to<br />

give necessary political support and,<br />

where possible, technical and financial<br />

assistance to the development of<br />

a project already launched in 2002<br />

by a consortium composed by OMV<br />

of Austria, MOL Group of Hungary,<br />

Bulgargaz of Bulgaria, Transgaz of<br />

Romania and BOTAŞ of Turkey: 3<br />

Nabucco.<br />

THE RISE AND FALL OF NABUCCO<br />

In fact, in 2002 the five-company<br />

consortium agreed to cooperate on<br />

the development of Nabucco, a projected<br />

3,800 kilometers (km) long<br />

pipeline with a capacity of 31 billion<br />

cubic metres per year (bcm/year)<br />

designed to carry natural gas extracted<br />

in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan,<br />

Iraq, Iran and Egypt to Southeast<br />

and Central Europe via Turkey. 4<br />

The Nabucco project immediately<br />

got an unprecedented political support<br />

from Turkey, the EU and the<br />

United States (US).<br />

2.<br />

European Commission, Second Strategic Energy Review – An EU Energy Security and Solidarity<br />

Action Plan. COM(20<strong>08</strong>) 781 final, 13 November 20<strong>08</strong>.<br />

3.<br />

The consortium was successively extended to RWE of Germany in 20<strong>08</strong>.<br />

4.<br />

Gas flows from these producing countries would have reached the Turkish border as follow: via the<br />

South Caucasus Pipeline in the case of Azerbaijan; via Iran or the planned Trans-<strong>Caspian</strong> Pipeline in<br />

the case of Turkmenistan; via the planned extension of the Arab Gas Pipeline in the case of Iraq; via<br />

the Arab Gas Pipeline in the case of Egypt.

FIGURE 1<br />

The Genesis of the Southern Gas Corridor: The Original Concept of Nabucco<br />

Source: Authors’ elaboration.<br />

Strong of the political backing<br />

For Turkey the project represented<br />

pendency on Russia. 6 the five transit countries in 2011. 11<br />

a unique opportunity to realize its of Turkey, the EU and the US, the<br />

long-term strategic objective of becoming<br />

Nabucco project gradually advanced<br />

a key energy corridor be-<br />

tween hydrocarbon rich countries in with the signature of the<br />

joint venture agreement between<br />

the East and energy importing European<br />

the five companies initially in-<br />

markets in the West.<br />

volved in the consortium in 2005, 7<br />

with the signature of a declaration<br />

For the EU the project represented<br />

calling for the acceleration of the<br />

a major opportunity to diversify its<br />

Nabucco project by the EC and energy<br />

natural gas supplies away from Russia.<br />

For this reason Nabucco not only<br />

ministers from Austria, Hungary, Romania,<br />

Bulgaria and Turkey in 2006<br />

got the financial support of the EU 5<br />

with the signature of the first<br />

but also became the flagship project<br />

contract to supply natural<br />

of the Southern Gas Corridor.<br />

gas from Azerbaijan in 20<strong>08</strong>, 9<br />

For the US the project represented with the signature of the intergovernmental<br />

an important geopolitical asset to<br />

agreement between<br />

reduce the EU natural gas dependency<br />

on Russia, exactly as the Baku-<br />

Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline served in<br />

the 1990s to reduce the EU oil de-<br />

the five transit countries in 2009 10<br />

and, finally, with the signature of the<br />

project support agreements between<br />

the Nabucco consortium and each of<br />

23<br />

CASPIAN REPORT, FALL <strong>2014</strong><br />

5.<br />

The European Commission awarded a grant in the amount of 50 percent of the estimated total<br />

eligible cost of the feasibility study including market analysis, and technical, economic and financial<br />

studies.<br />

6.<br />

“U.S. throws weight behind EU’s Nabucco pipeline”, in Reuters, 22 February 20<strong>08</strong>.<br />

7.<br />

“Nabucco Partners Sign Joint Venture Agreement”, in Middle East Economic Survey, 11 July 2005.<br />

8.<br />

“EU Commission, Ministers Agree To Accelerate Nabucco Gas Project”, in Middle East Economic<br />

Survey, 3 July 2006.<br />

9.<br />

“Azeri Energy Minister Announces Readiness To Join Nabucco Project”, in Middle East Economic<br />

Survey, 8 September 20<strong>08</strong>.<br />

10.<br />

“Nabucco Partners Sign Intergovernmental Agreement”, in Middle East Economic Survey, 20 July<br />

2009.<br />

11.<br />

“Nabucco Legally Finalized as Transit States Sign Project Support Agreements”, in Novinite, 8 June<br />

2011.

MANFRED HAFNER<br />

24<br />

Notwithstanding the strong political<br />

commitment of the five transit countries<br />

and the unprecedented political<br />

support of the EU and the US, the<br />

Nabucco project ultimately failed,<br />

mainly because of commercial and<br />

financial reasons: a very large scale<br />

pipeline project combined with a<br />

hugely uncertain demand outlook<br />

and the potential competition of<br />

South Stream. Moreover, the project<br />

promoters were mainly mid-size<br />

companies who have to rely on project<br />

finance and bank loans, and the<br />

banks ask for guarantees and long<br />

term ship or pay contracts which<br />

the market could not deliver. Furthermore,<br />

another major element of<br />

uncertainty for the Nabucco project<br />

was related to the fact that -with the<br />

only exception of Azerbaijan- all the<br />

potential suppliers were facing major<br />

difficulties to materialize their<br />

willingness to evacuate gas to Europe<br />

via Turkey.<br />

THE EVOLUTION OF THE<br />

SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR<br />

BEYOND NABUCCO: TANAP AND<br />

TAP<br />

Taking into consideration the insurmountable<br />

commercial and financial<br />

barriers that the Nabucco<br />

project was facing, Azerbaijan<br />

-clearly the gas producing country<br />

most interested on the development<br />

of the Southern Gas Corridor 12<br />

- completely reshaped the Southern<br />

Gas Corridor game in 2011 by rapidly<br />

conceptualizing its own infrastructure<br />

project to evacuate future<br />

gas flows from Shah Deniz Phase II<br />

to Turkey: the Trans Anatolian Natural<br />

Gas Pipeline (TANAP).<br />

TANAP, a projected 2,000 km-long<br />

gas pipeline with a capacity of 16<br />

bcm/year, has been designed to supply<br />

6 bcm/year to Turkey by 2018<br />

and 10 bcm/year to Europe by 2019.<br />

TANAP will run from the Georgian-<br />

Turkish border to the Turkish-Greek<br />

border, but the exact route of the<br />

pipeline is not clear yet. TANAP will<br />

receive its gas from the South Caucasus<br />

Pipeline (SCP), a pipeline already<br />

evacuating gas from the Azerbaijani<br />

Shah Deniz field to Turkey,<br />

which will be expanded in order to<br />

accommodate the new volumes of<br />

gas coming from Shah Deniz Phase<br />

II and going to TANAP.<br />

On the contrary of Nabucco, TAN-<br />

AP was not born as a multilateral<br />

project but rather as a producer<br />

driven bilateral project between<br />

Azerbaijan and Turkey. The initial<br />

act of the project -occurred in December<br />

2011- was the signature<br />

of a Memorandum of Understanding<br />

(MoU) between Azerbaijan and<br />

Turkey establishing a consortium<br />

to build and operate the pipeline. 13<br />

This initial step was then followed<br />

by the signature of a binding intergovernmental<br />

agreement on TANAP<br />

made by Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev<br />

and Turkey’s (at the time) Prime<br />

Minister Erdoğan in June 2012. 14<br />

Of course this bilateral relation was<br />

not symmetric, but rather unbalanced<br />

in favour of Azerbaijan. In fact,<br />

the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan<br />

(SOCAR) was initially set to hold an<br />

80 percent stake in the project, leaving<br />

only the remaining 20 percent<br />

to the Turkish partners (15 percent<br />

to BOTAŞ and 5 percent to TPAO).<br />

12.<br />

Not only because of the investments already made on its Shah Deniz natural gas field, but also<br />

because of the need to reach a final investment decision for Shah Deniz Phase II (a decision<br />

that finally arrived on December 17, 2013).<br />

13.<br />

“Turkey and Azerbaijan Sign MoU for TANAP Pipeline”, in Middle East Economic Survey, 9<br />

January 2012.<br />

14.<br />

“TANAP Project, the Silk Road of Energy, Has Been Signed”, http://www.tanap.com, 26 June<br />

2012.

This figure has changed over time,<br />

to a more balanced structure entailing<br />

a share of 58 percent for SOCAR,<br />

25 percent for BOTAŞ, 5 percent<br />

for TPAO and 12 percent for BP. 15<br />

Notwithstanding this realignment of<br />

shares, SOCAR is set to continue to<br />

retain a controlling share of TANAP<br />

and operatorship of the line in the<br />

future. In fact, TANAP is crucially<br />

important for the Azerbaijani state<br />

owned company, as it will have a key<br />

role in the delivery of gas from its<br />

Shah Deniz field further down the<br />

supply chain to Europe, rather than<br />

selling at its border.<br />

Among other factors, a key element<br />

of strength of the TANAP project<br />

relates to its financing: because of<br />

the considerable oil revenues provided<br />