Managing the Miombo Woodlands of Southern Africa - PROFOR

Managing the Miombo Woodlands of Southern Africa - PROFOR

Managing the Miombo Woodlands of Southern Africa - PROFOR

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Charcoal became more costly to produce and to get to <strong>the</strong> market, which reduced demand, but<br />

created good opportunities for intermediaries to capture extra revenues, usually from bribes (box<br />

3.1). With production pushed out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> legal domain, <strong>the</strong> forestry department had less control<br />

over <strong>the</strong> process. It became problematic for <strong>the</strong> forest department to collect stumpage fees even<br />

if charcoal was made in forest reserves, nor was it able to advise or train charcoal producers on<br />

woodland management and charcoal production because this would have been illegal. More<br />

recently, Kambewa et al. (2007) also conclude that current efforts in Malawi to discourage charcoal<br />

making are expensive and ineffective.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recent literature on forest governance confi rms that a plethora <strong>of</strong> national-level<br />

regulations does little more than improve <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> petty <strong>of</strong>fi cials to extract informal payments.<br />

Such informal taxation results in lower pr<strong>of</strong>i t margins to producers and traders. In an impassioned<br />

report on <strong>the</strong> Mozambique timber market, Mackenzie (2006) concluded that <strong>of</strong>fi cial agencies were<br />

presiding over and colluding with abuses that makes a “mockery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> governance:<br />

taking bribes for issuing licenses, approving management plans, concessions and export permits,<br />

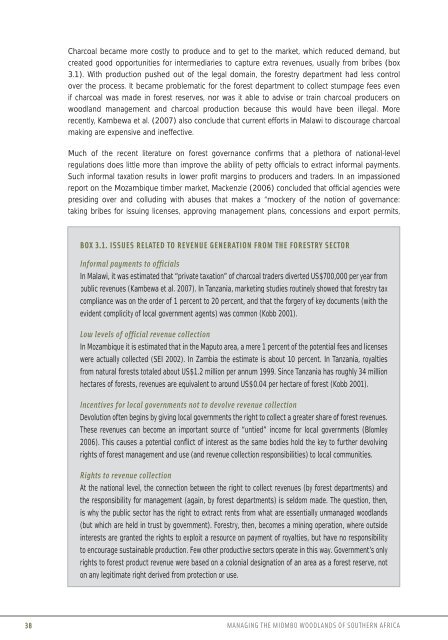

BOX 3.1. ISSUES RELATED TO REVENUE GENERATION FROM THE FORESTRY SECTOR<br />

Informal payments to <strong>of</strong>ficials<br />

In Malawi, it was estimated that “private taxation” <strong>of</strong> charcoal traders diverted US$700,000 per year from<br />

public revenues (Kambewa et al. 2007). In Tanzania, marketing studies routinely showed that forestry tax<br />

compliance was on <strong>the</strong> order <strong>of</strong> 1 percent to 20 percent, and that <strong>the</strong> forgery <strong>of</strong> key documents (with <strong>the</strong><br />

evident complicity <strong>of</strong> local government agents) was common (Kobb 2001).<br />

Low levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial revenue collection<br />

In Mozambique it is estimated that in <strong>the</strong> Maputo area, a mere 1 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> potential fees and licenses<br />

were actually collected (SEI 2002). In Zambia <strong>the</strong> estimate is about 10 percent. In Tanzania, royalties<br />

from natural forests totaled about US$1.2 million per annum 1999. Since Tanzania has roughly 34 million<br />

hectares <strong>of</strong> forests, revenues are equivalent to around US$0.04 per hectare <strong>of</strong> forest (Kobb 2001).<br />

Incentives for local governments not to devolve revenue collection<br />

Devolution <strong>of</strong>ten begins by giving local governments <strong>the</strong> right to collect a greater share <strong>of</strong> forest revenues.<br />

These revenues can become an important source <strong>of</strong> “untied” income for local governments (Blomley<br />

2006). This causes a potential conflict <strong>of</strong> interest as <strong>the</strong> same bodies hold <strong>the</strong> key to fur<strong>the</strong>r devolving<br />

rights <strong>of</strong> forest management and use (and revenue collection responsibilities) to local communities.<br />

Rights to revenue collection<br />

At <strong>the</strong> national level, <strong>the</strong> connection between <strong>the</strong> right to collect revenues (by forest departments) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> responsibility for management (again, by forest departments) is seldom made. The question, <strong>the</strong>n,<br />

is why <strong>the</strong> public sector has <strong>the</strong> right to extract rents from what are essentially unmanaged woodlands<br />

(but which are held in trust by government). Forestry, <strong>the</strong>n, becomes a mining operation, where outside<br />

interests are granted <strong>the</strong> rights to exploit a resource on payment <strong>of</strong> royalties, but have no responsibility<br />

to encourage sustainable production. Few o<strong>the</strong>r productive sectors operate in this way. Government’s only<br />

rights to forest product revenue were based on a colonial designation <strong>of</strong> an area as a forest reserve, not<br />

on any legitimate right derived from protection or use.<br />

38 MANAGING THE MIOMBO WOODLANDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA