Resonant nonlinear magneto-optical effects in atomsâ - The Budker ...

Resonant nonlinear magneto-optical effects in atomsâ - The Budker ...

Resonant nonlinear magneto-optical effects in atomsâ - The Budker ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

6<br />

A <br />

n <br />

(a)<br />

Na D1<br />

(b)<br />

Na D2<br />

A <br />

Ω Ω <br />

Dichroism<br />

A A <br />

A A <br />

(a)<br />

gΜB/@ ⩵ <br />

(b)<br />

n <br />

n n <br />

n n <br />

Birefr<strong>in</strong>gence<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

220 C<br />

195 C<br />

177 C<br />

experiment<br />

theory<br />

155 C<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

220 C<br />

195 C<br />

177 C<br />

155 C<br />

gΜB/@ ⩵ <br />

(c)<br />

Frequency (Ω)<br />

0<br />

0<br />

140 C<br />

1<br />

(c)<br />

2<br />

Na D1<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

140 C<br />

1 2 3<br />

(d) Na D2<br />

4<br />

5<br />

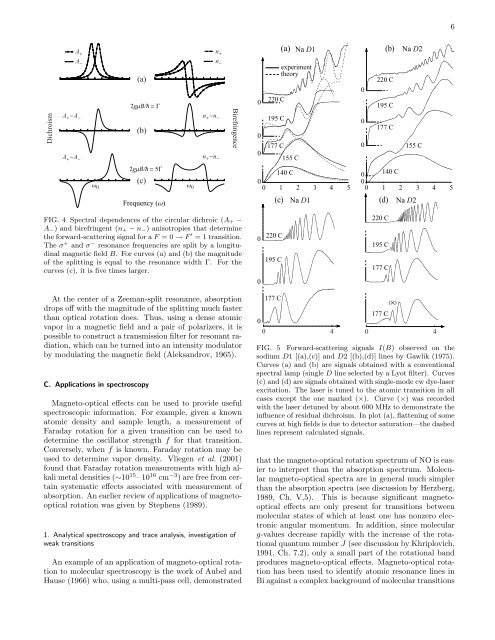

FIG. 4 Spectral dependences of the circular dichroic (A + −<br />

A − ) and birefr<strong>in</strong>gent (n + − n − ) anisotropies that determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

the forward-scatter<strong>in</strong>g signal for a F = 0 → F ′ = 1 transition.<br />

<strong>The</strong> σ + and σ − resonance frequencies are split by a longitud<strong>in</strong>al<br />

magnetic field B. For curves (a) and (b) the magnitude<br />

of the splitt<strong>in</strong>g is equal to the resonance width Γ. For the<br />

curves (c), it is five times larger.<br />

0<br />

0<br />

220 C<br />

195 C<br />

220 C<br />

195 C<br />

177 C<br />

At the center of a Zeeman-split resonance, absorption<br />

drops off with the magnitude of the splitt<strong>in</strong>g much faster<br />

than <strong>optical</strong> rotation does. Thus, us<strong>in</strong>g a dense atomic<br />

vapor <strong>in</strong> a magnetic field and a pair of polarizers, it is<br />

possible to construct a transmission filter for resonant radiation,<br />

which can be turned <strong>in</strong>to an <strong>in</strong>tensity modulator<br />

by modulat<strong>in</strong>g the magnetic field (Aleksandrov, 1965).<br />

C. Applications <strong>in</strong> spectroscopy<br />

Magneto-<strong>optical</strong> <strong>effects</strong> can be used to provide useful<br />

spectroscopic <strong>in</strong>formation. For example, given a known<br />

atomic density and sample length, a measurement of<br />

Faraday rotation for a given transition can be used to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e the oscillator strength f for that transition.<br />

Conversely, when f is known, Faraday rotation may be<br />

used to determ<strong>in</strong>e vapor density. Vliegen et al. (2001)<br />

found that Faraday rotation measurements with high alkali<br />

metal densities (∼10 15 – 10 16 cm −3 ) are free from certa<strong>in</strong><br />

systematic <strong>effects</strong> associated with measurement of<br />

absorption. An earlier review of applications of <strong>magneto</strong><strong>optical</strong><br />

rotation was given by Stephens (1989).<br />

1. Analytical spectroscopy and trace analysis, <strong>in</strong>vestigation of<br />

weak transitions<br />

An example of an application of <strong>magneto</strong>-<strong>optical</strong> rotation<br />

to molecular spectroscopy is the work of Aubel and<br />

Hause (1966) who, us<strong>in</strong>g a multi-pass cell, demonstrated<br />

0<br />

177 C<br />

177 C<br />

0 4 0 4<br />

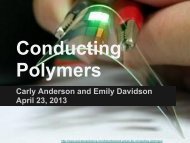

FIG. 5 Forward-scatter<strong>in</strong>g signals I(B) observed on the<br />

sodium D1 [(a),(c)] and D2 [(b),(d)] l<strong>in</strong>es by Gawlik (1975).<br />

Curves (a) and (b) are signals obta<strong>in</strong>ed with a conventional<br />

spectral lamp (s<strong>in</strong>gle D l<strong>in</strong>e selected by a Lyot filter). Curves<br />

(c) and (d) are signals obta<strong>in</strong>ed with s<strong>in</strong>gle-mode cw dye-laser<br />

excitation. <strong>The</strong> laser is tuned to the atomic transition <strong>in</strong> all<br />

cases except the one marked (×). Curve (×) was recorded<br />

with the laser detuned by about 600 MHz to demonstrate the<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence of residual dichroism. In plot (a), flatten<strong>in</strong>g of some<br />

curves at high fields is due to detector saturation—the dashed<br />

l<strong>in</strong>es represent calculated signals.<br />

that the <strong>magneto</strong>-<strong>optical</strong> rotation spectrum of NO is easier<br />

to <strong>in</strong>terpret than the absorption spectrum. Molecular<br />

<strong>magneto</strong>-<strong>optical</strong> spectra are <strong>in</strong> general much simpler<br />

than the absorption spectra (see discussion by Herzberg,<br />

1989, Ch. V,5). This is because significant <strong>magneto</strong><strong>optical</strong><br />

<strong>effects</strong> are only present for transitions between<br />

molecular states of which at least one has nonzero electronic<br />

angular momentum. In addition, s<strong>in</strong>ce molecular<br />

g-values decrease rapidly with the <strong>in</strong>crease of the rotational<br />

quantum number J (see discussion by Khriplovich,<br />

1991, Ch. 7.2), only a small part of the rotational band<br />

produces <strong>magneto</strong>-<strong>optical</strong> <strong>effects</strong>. Magneto-<strong>optical</strong> rotation<br />

has been used to identify atomic resonance l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong><br />

Bi aga<strong>in</strong>st a complex background of molecular transitions<br />

(/\)