Through a Glass Darkly: Measuring Loss Under ... - Land Use Law

Through a Glass Darkly: Measuring Loss Under ... - Land Use Law

Through a Glass Darkly: Measuring Loss Under ... - Land Use Law

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

600 THE URBAN LAWYER VOL. 39, NO. 3 SUMMER 2007<br />

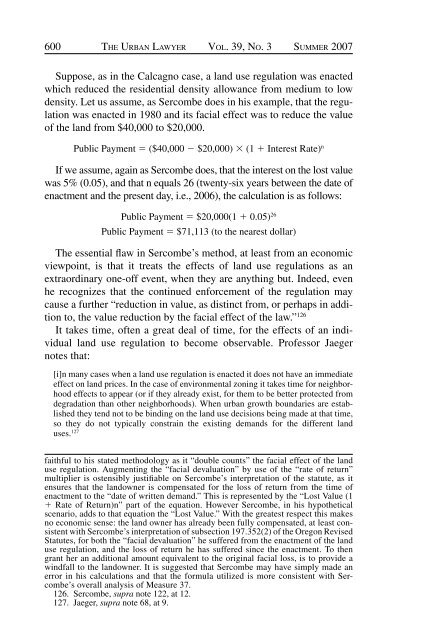

Suppose, as in the Calcagno case, a land use regulation was enacted<br />

which reduced the residential density allowance from medium to low<br />

density. Let us assume, as Sercombe does in his example, that the regulation<br />

was enacted in 1980 and its facial effect was to reduce the value<br />

of the land from $40,000 to $20,000.<br />

Public Payment ($40,000 $20,000) (1 Interest Rate) n<br />

If we assume, again as Sercombe does, that the interest on the lost value<br />

was 5% (0.05), and that n equals 26 (twenty-six years between the date of<br />

enactment and the present day, i.e., 2006), the calculation is as follows:<br />

Public Payment $20,000(1 0.05) 26<br />

Public Payment $71,113 (to the nearest dollar)<br />

The essential flaw in Sercombe’s method, at least from an economic<br />

viewpoint, is that it treats the effects of land use regulations as an<br />

extraordinary one-off event, when they are anything but. Indeed, even<br />

he recognizes that the continued enforcement of the regulation may<br />

cause a further “reduction in value, as distinct from, or perhaps in addition<br />

to, the value reduction by the facial effect of the law.” 126<br />

It takes time, often a great deal of time, for the effects of an individual<br />

land use regulation to become observable. Professor Jaeger<br />

notes that:<br />

[i]n many cases when a land use regulation is enacted it does not have an immediate<br />

effect on land prices. In the case of environmental zoning it takes time for neighborhood<br />

effects to appear (or if they already exist, for them to be better protected from<br />

degradation than other neighborhoods). When urban growth boundaries are established<br />

they tend not to be binding on the land use decisions being made at that time,<br />

so they do not typically constrain the existing demands for the different land<br />

uses. 127<br />

faithful to his stated methodology as it “double counts” the facial effect of the land<br />

use regulation. Augmenting the “facial devaluation” by use of the “rate of return”<br />

multiplier is ostensibly justifiable on Sercombe’s interpretation of the statute, as it<br />

ensures that the landowner is compensated for the loss of return from the time of<br />

enactment to the “date of written demand.” This is represented by the “Lost Value (1<br />

Rate of Return)n” part of the equation. However Sercombe, in his hypothetical<br />

scenario, adds to that equation the “Lost Value.” With the greatest respect this makes<br />

no economic sense: the land owner has already been fully compensated, at least consistent<br />

with Sercombe’s interpretation of subsection 197.352(2) of the Oregon Revised<br />

Statutes, for both the “facial devaluation” he suffered from the enactment of the land<br />

use regulation, and the loss of return he has suffered since the enactment. To then<br />

grant her an additional amount equivalent to the original facial loss, is to provide a<br />

windfall to the landowner. It is suggested that Sercombe may have simply made an<br />

error in his calculations and that the formula utilized is more consistent with Sercombe’s<br />

overall analysis of Measure 37.<br />

126. Sercombe, supra note 122, at 12.<br />

127. Jaeger, supra note 68, at 9.<br />

ABA-TUL-07-0701-Sullivan.indd 600<br />

9/18/07 10:43:44 AM