BD Hardwick Hall_040211.pdf - Sergison Bates architects

BD Hardwick Hall_040211.pdf - Sergison Bates architects

BD Hardwick Hall_040211.pdf - Sergison Bates architects

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

14<br />

FRIDAY FEBRUARY 4 2011<br />

WWW.<strong>BD</strong>ONLINE.CO.UK<br />

WWW.<strong>BD</strong>ONLINE.CO.UK FRIDAY FEBRUARY 4 2011 15<br />

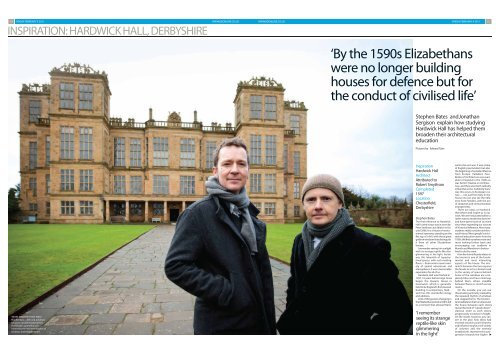

INSPIRATION: HARDWICK HALL, DERBYSHIRE<br />

‘By the 1590s Elizabethans<br />

were no longer building<br />

houses for defence but for<br />

the conduct of civilised life’<br />

Stephen <strong>Bates</strong> andJonathan<br />

<strong>Sergison</strong> explain how studying<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong> has helped them<br />

broaden their architectural<br />

education<br />

Pictures by Edward Tyler<br />

“MORE WINDOW THAN WALL”<br />

Stephen <strong>Bates</strong> (left) and Jonathan<br />

<strong>Sergison</strong> outside <strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong>.<br />

The facade’s symmetry was<br />

created by the repeated rhythm of<br />

windows and stepped forms.<br />

Inspiration<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong><br />

Architect<br />

Attributed to<br />

Robert Smythson<br />

Completed<br />

1597<br />

Location<br />

Chesterfield,<br />

Derbyshire<br />

‘I remember<br />

seeing its strange<br />

reptile-like skin<br />

glimmering<br />

in the light’<br />

Stephen <strong>Bates</strong><br />

The first reference to <strong>Hardwick</strong><br />

<strong>Hall</strong> I came across was in a text by<br />

Peter Smithson, but I didn’t visit it<br />

until 2006. It is a house of monumental<br />

symmetry standing on the<br />

flat top of a hill, with these great<br />

gridiron windows that distinguish<br />

it from all other Elizabethan<br />

houses.<br />

I remember seeing it in sunlight<br />

with its strange reptile-like skin<br />

glimmering in the light. Inside<br />

was this labyrinth of tapestrylined<br />

spaces, with rush matting<br />

floors — from room to room a variety<br />

of spatial adventures and<br />

atmospheres. It was a memorable<br />

experience for all of us.<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong> was finished in<br />

1597, 16 years before Inigo Jones<br />

began the Queen’s House in<br />

Greenwich, which is generally<br />

held to be England’s first classical<br />

building. In comparison, <strong>Hardwick</strong><br />

has this wonderful energy<br />

and oddness.<br />

A lot of things were changing in<br />

the Elizabethan period and this led<br />

to a moment that allowed <strong>Hardwick</strong><br />

to be as it was. It was a time<br />

of English provincialism but also<br />

the beginning of outside influence<br />

from Europe. Palladio’s Four<br />

Books of Architecture was available<br />

in England in the 1560s as<br />

was Serlio’s Treatise on Architecture,<br />

and they were both radically<br />

influential works. Suddenly there<br />

was this access to European culture<br />

— not just from Italy. In the<br />

house one can also see the influence<br />

from Flanders, with the use<br />

of strapwork and vertical window<br />

arrangements.<br />

There are ideas at <strong>Hardwick</strong><br />

that inform and inspire us in our<br />

work. We were educated within a<br />

rather narrow modernist doctrine<br />

and have spent much of our time<br />

since then expanding our sources<br />

of historical reference. How many<br />

students really consider architectural<br />

history? Most people’s architectural<br />

education starts from the<br />

1930s. We find ourselves more and<br />

more looking further back and<br />

encouraging our students in<br />

Munich and Mendrisio in Switzerland<br />

to do the same.<br />

How the formal facade relates to<br />

the interior is one of the fundamental<br />

and most interesting<br />

aspects of the house. The mismatch<br />

between the two requires<br />

the facade to act as a formal mask<br />

to the variety of spaces behind.<br />

Some of the windows are completely<br />

false and have chimneys<br />

behind them, others straddle<br />

between floors or stretch across<br />

rooms.<br />

On the outside, you can see<br />

this amazing symmetry created by<br />

the repeated rhythm of windows<br />

and stepped forms. The horizontal<br />

entablatures that run all around<br />

the house between each storey<br />

reveal this kind of “upside-down”<br />

classical order as each storey<br />

progressively increases in height.<br />

On the inside, however, you can<br />

see in the plan how ideas had<br />

evolved around social hierarchy<br />

and influence to give a rich variety<br />

of volumes and the external<br />

entablatures represent this progression<br />

towards the higher

16<br />

FRIDAY FEBRUARY 4 2011<br />

WWW.<strong>BD</strong>ONLINE.CO.UK<br />

WWW.<strong>BD</strong>ONLINE.CO.UK FRIDAY FEBRUARY 4 2011 17<br />

INSPIRATION: HARDWICK HALL, DERBYSHIRE<br />

HIGH GREAT CHAMBER<br />

This is the grandest of the formal rooms<br />

at <strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong>. Bess would have sat in<br />

state under a canopy similar to this in the<br />

Great Chamber, which leads to the<br />

Withdrawing Chamber though a doorway<br />

under the tapestry to the right.<br />

A 16th century<br />

statement of<br />

wealth<br />

Bess of <strong>Hardwick</strong>, the<br />

Countess of Shrewsbury,<br />

was the richest woman in<br />

England in the 16th century<br />

after Queen Elizabeth I<br />

herself. She was the<br />

client for <strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong>,<br />

built as a statement of her<br />

wealth and power, writes<br />

Pamela Buxton .<br />

It is thought to have been<br />

designed by Robert<br />

Smythson, who had already<br />

worked on grand houses at<br />

Longleat and Wollaton <strong>Hall</strong>.<br />

Glass was a luxury in the<br />

16th century yet <strong>Hardwick</strong>’s<br />

main feature is its six great<br />

towers and its exceptionally<br />

large and numerous<br />

windows. This led to the<br />

saying “<strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong>, more<br />

glass than wall”.<br />

LONG GALLERY<br />

Portraits and tapestries adorn the second floor Long Gallery, which measures 51m long x 8m high x 6.7m wide.<br />

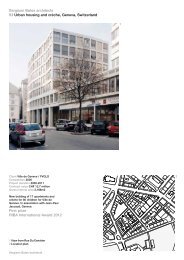

MAIN STAIRCASE<br />

The broad, stone stairs lead up to a lofty vestibule to the High<br />

Great Chamber on the second floor.<br />

Ahead of its time<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong>, situated between<br />

Chesterfield and Mansfield,<br />

was one of the first English<br />

grand houses to interpret<br />

Renaissance architecture,<br />

with Smythson perhaps<br />

influenced by Palladio and<br />

Serlio in his incorporation of<br />

colonnades between the<br />

tower at the back and front<br />

of the house.<br />

It was also the first time<br />

that the great hall was built<br />

on an axis through the<br />

centre of the house rather<br />

than at right angles to the<br />

entrance. The state rooms<br />

are on the second floor,<br />

including one of the largest<br />

and more ceremonial rooms.<br />

The alignment of the central<br />

hall was completely new, as the<br />

earlier medieval hall had been<br />

positioned lengthways through<br />

the house. This is indicative of<br />

how the central room ofl arge<br />

houses was changing from being<br />

the principal gathering space to a<br />

more ceremonial one. At this<br />

point, the Elizabethans were no<br />

longer building houses for defence<br />

but for the conduct of civilised life.<br />

Rather than following the convention<br />

of the time, when the principal<br />

staircase was an object, made<br />

from wood like a piece off urniture,<br />

at <strong>Hardwick</strong> we encounter a<br />

wide stone stairway. I particularly<br />

like this stairway, which is experienced<br />

as a beautiful sequence of<br />

spaces, rising through compressed<br />

tall spaces with straight tapered<br />

flights that change direction and<br />

re-orientate the visitor until they<br />

arrive at a vestibule on the second<br />

floor, small in plan but extraordinarily<br />

high. This opens on to the<br />

High Great Chamber — the equivalent<br />

in volume to a modern day<br />

five-bedroom house.<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong> predates the enfilade,<br />

the sequence of connecting rooms<br />

with aligned doorways, and has a<br />

more discontinuous and elaborate<br />

arrangement, with doors sometimes<br />

positioned diagonally across<br />

space. A plan ofi nterconnected<br />

rooms, without corridors, is a constant<br />

reference for us in our work.<br />

Here there is a sense ofi ntrigue<br />

and a degree of surprise and<br />

drama to the experience of moving<br />

through the house, no more so<br />

than when you come across the<br />

magnificent Long Gallery via a<br />

small door in the corner, partially<br />

covered by a looped tapestry!<br />

TURRET ROOMS<br />

One of the turret rooms, where<br />

select guests would eat<br />

sweetmeats.<br />

I find it inspiring that the plan<br />

clearly supports a particular way<br />

ofl ife and is not generalised or<br />

ordered in an abstract way. Bess’s<br />

private rooms were on the first<br />

floor, but the most important state<br />

rooms were on the second floor.<br />

She received her visitors in the<br />

Great Chamber and would lead<br />

favoured guests into an adjacent<br />

room through a side door. Select<br />

friends would eat sweetmeats or<br />

meet intimately in dining rooms in<br />

each of the towers, accessed by<br />

walking across the roof.<br />

‘<strong>Hardwick</strong> wasn’t<br />

refined. There’s a<br />

roughness in the<br />

plasterwork, and<br />

in the junction<br />

of elements’<br />

It’s highly evocative to imagine<br />

that the house would have been<br />

occupied by up to 60 people at any<br />

one time, providing for both Bess’s<br />

household and that of her daughter’s.<br />

The atmosphere must have<br />

been one of great conviviality and<br />

hustle and bustle. There wasn’t<br />

this hierarchical Upstairs-Downstairs<br />

separation of masters and<br />

servants — servants would sleep<br />

on straw mattresses pulled out<br />

from underneath the mistress’s<br />

bed or on the landings of the stairway.<br />

Rooms like the dining room<br />

would have been used by both<br />

high servants and the family at different<br />

times of the day.<br />

The elaborate plaster ceilings<br />

and friezes were designed for<br />

candlelight. The strapwork and<br />

pendants would have been alive<br />

with constantly moving shadows.<br />

Ceilings were designed to interrupt<br />

and diversify the varying<br />

light, to “use” not to eliminate<br />

shadows, as so many modern ceilings<br />

do.<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong> wasn’t refined.<br />

There’s a roughness and directness<br />

in the plasterwork, and in the<br />

junction of elements, between<br />

beam and column or balustrade<br />

and stairway, for example. It is a<br />

sensibility that I feel is important<br />

to work with as an architect. I am<br />

interested in a “carefully careless”<br />

attitude. The design is still highly<br />

considered, but there is a controlled<br />

looseness.<br />

I look forward to coming back<br />

to <strong>Hardwick</strong> again. I will be here<br />

in the spring with my students<br />

from the TU in Munich, as we will<br />

be making a tour of English country<br />

houses — mainly early classical-influenced<br />

ones — including<br />

<strong>Hardwick</strong>.<br />

NORTH ELEVATION<br />

Bess’s monogram ES is incorporated frequently into the house, most notably in the tower parapets.<br />

Jonathan <strong>Sergison</strong><br />

I have been aware of <strong>Hardwick</strong><br />

<strong>Hall</strong> as a project for a long time, as<br />

it appears in Summerson’s history<br />

of British Architecture, was<br />

referred to by the Smithsons and,<br />

more recently, by Mark Girouard<br />

in his Life in the English Country<br />

House. But my interest really<br />

found focus through Stephen’s<br />

enthusiasm.<br />

There are a number of strands<br />

that we find relevant. The proportions<br />

employed in the organisation<br />

of the facade are very particular,<br />

‘It’s an example of<br />

what an English<br />

architecture<br />

might be’<br />

they subvert the language of the<br />

classical order by placing the most<br />

significant rooms on the top floor,<br />

rather than on the first, the piano<br />

nobile. This leads to an upside<br />

down feeling which is disquieting<br />

and wonderful.<br />

The project was known to me<br />

for the way it uses glass, an expression<br />

of enormous luxury for its<br />

time. You can imagine the difficulty<br />

transporting this material<br />

presented in 1590. The attention<br />

Walter Gropius’s Fagus factory of<br />

1911 received gives us an idea of<br />

how unprecedented this was. And<br />

you can imagine what it might<br />

have been like to be travelling<br />

through England at the end of the<br />

16th century and encounter this<br />

building.<br />

Nothing ever compensates for<br />

really seeing a project as a physical<br />

entity. What is not communicated<br />

in the plans, sections and<br />

photographs of this building is the<br />

manner in which this house sits in<br />

the landscape, the way it commands<br />

its immediate environment.<br />

It is in no way demure, but<br />

is brash and imposing, a character<br />

clearly attributable to the woman<br />

it was built for.<br />

We can only speculate on the<br />

way it was developed as a project.<br />

Clearly, it has ideas that can be<br />

connected to Robert Smythson’s<br />

earlier body of built work, but<br />

there is much that must be due,<br />

one suspects, to a somewhat<br />

charged relationship between<br />

client and master mason.<br />

Above all, <strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong> offers<br />

an example of what an English<br />

architecture might be. It is a little<br />

irreverent, certainly in relation to<br />

the canon of classicism, and proportion<br />

is used in a personal rather<br />

than correct manner. There is a<br />

level of slackness in the way things<br />

are put together: parts of the<br />

building have junctions that are<br />

wonderfully relaxed, like the way<br />

a volume meets a beam on the<br />

staircase, or where beams run into<br />

window heads.<br />

We enjoy the looseness between<br />

the expression of the facade and<br />

the way the section is really<br />

arranged. This is far from being<br />

pure. And the organisation of the<br />

sequence of spaces in the house is<br />

rich and elaborate. It is unpredictable<br />

and leads to a complex<br />

matrix of social possibilities.<br />

These are ideas that we hold in<br />

high regard, and it is interesting<br />

that they are embodied in a work<br />

that is more than 400 years old.<br />

Stephen <strong>Bates</strong> and Jonathan<br />

<strong>Sergison</strong> were speaking to<br />

Pamela Buxton.<br />

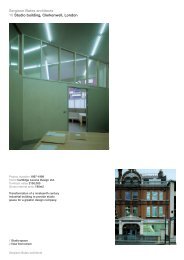

SECOND FLOOR<br />

8<br />

FIRST FLOOR<br />

GROUND FLOOR<br />

7<br />

7<br />

5<br />

6<br />

8<br />

6<br />

5<br />

1<br />

4<br />

1<br />

5<br />

1<br />

2<br />

2<br />

4<br />

3 2<br />

4<br />

3<br />

3<br />

1 Long Gallery<br />

2 Upper landing<br />

3 High Great<br />

Chamber<br />

4 Withdrawing<br />

Chamber<br />

5 Green velvet<br />

6 Mary Queen<br />

of Scot’s room<br />

7 Blue room<br />

8 North<br />

staircase<br />

1 Upper portion<br />

of hall<br />

2 Landing<br />

3 Bedchambers<br />

4 Drawing room<br />

5 Gallery<br />

6 Dining room<br />

7 Cut velvet<br />

bedroom<br />

8 Chapel<br />

1 Great <strong>Hall</strong><br />

2 Main staircase<br />

3 William<br />

Cavendish’s<br />

chamber<br />

4 Duke’s room<br />

5 Kitchen<br />

N<br />

Bess of <strong>Hardwick</strong>.<br />

long galleries in any English<br />

country home, and a great<br />

chamber with a frieze of<br />

hunting scenes that<br />

incorporates real timber for<br />

the trees. The gallery is<br />

covered in tapestries bought<br />

second hand by Bess and<br />

overworked with her own<br />

coat of arms.<br />

Malfoy Manor<br />

The house became the<br />

secondary residence of the<br />

Dukes of Devonshire, who<br />

lived nearby at Chatsworth<br />

and as a result has been little<br />

altered, with many of the<br />

current contents traceable to<br />

an inventory of 1601.<br />

It has been a National<br />

Trust property since 1959,<br />

and has undergone lengthy<br />

repairs. Architects Rodney<br />

Melville & Partners are<br />

working on a renovation and<br />

extension of the nearby<br />

stableyard buildings to<br />

provide a new shop and<br />

restaurant. <strong>Hardwick</strong> <strong>Hall</strong><br />

recently featured as Malfoy<br />

Manor in the latest Harry<br />

Potter film.