Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Susan Hilty<br />

Moving Forward<br />

from the Drought<br />

The Drought of <strong>2012</strong> was the big<br />

news this past summer. How long<br />

will it last? Previous droughts have<br />

been multiple years more often than<br />

single years. The 1810s drought lasted six years, the 1860s drought lasted<br />

seven years, the 1930s drought was eight years, the 1950s and the 1980s<br />

droughts lasted five years. Wet years often occur during droughts; for<br />

example the worst years of 1934 and 1936 were separated by a wet 1935.<br />

Likewise, 1982 was exceptionally wet, breaking a string of dry years. There<br />

have been several two-year and single-year droughts; the most recent<br />

were 1988 and 2006. So, which will this one be? It already is two years<br />

if you include the southwest last year. Even if it’s a short-term drought,<br />

don’t expect any appreciable moisture until at least March.<br />

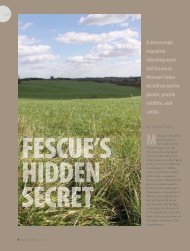

Throughout the summer, <strong>Missouri</strong> has had the worst pasture condition<br />

of any Midwestern state, rated 99% poor or very poor. It isn’t that we<br />

have been that much hotter or drier, but the state of our pastures is in part<br />

a reflection of decisions to convert 99.9 % of the tallgrass prairie to coolseason<br />

pasture, trees, or cropland. Isn’t fescue great?! Remember all that<br />

money made on fescue seed went to pay for fertilizer to ensure high seed<br />

and hay yields. Not much left over to buy hay now.<br />

As happened during previous droughts or dry summers, I received<br />

a lot of inquiries this past summer about planting native warm-season<br />

grasses for forage that would perform substantially better during dry<br />

weather than tall fescue. I also heard from past cooperators with native<br />

grasses who swore the grasses saved their farm or cow herd. You’d think<br />

more producers would take note, but many are willing to wait for a<br />

government handout. I’ve even seen some mowing their pastures even<br />

though there’s nothing but a couple goldenrods to clip off. Habits are hard<br />

to break, even in difficult economic times.<br />

The following article from Don McKenzie, Director of the National<br />

Bobwhite Conservation Initiative, sums up the opportunity to improve not<br />

only habitat for grassland wildlife, but improve the future for livestock<br />

producers throughout the Midwest. Don drafted a letter to the USDA,<br />

signed by a number of conservation organizations and agencies, that suggests<br />

a longer-term approach be taken following this drought that encourages<br />

producers to plant drought-resistant native grasses on part of their<br />

acreages.<br />

Encouraging for the future of native grasses is an article on cattlegrazing<br />

behavior by cattle producer and independent writer Heather Smith<br />

Thomas in the July, <strong>2012</strong> issue of Stockman Grass Farmer. Heather quotes<br />

Holly T. Boland, Ph.D., (Associate Research and Extension Professor, MAFES<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Research Unit, Mississippi State University) on Boland’s grazing<br />

studies in Virginia and Mississippi. “A lot of [New Zealand] focus is also on<br />

forage-finishing beef animals without grain. Here we’re studying pastures<br />

Native Warm-Season Grass News<br />

A Landowner’s Guide To Wildlife-Friendly Grasslands<br />

we’ve renovated back to native warm-season grasses such as indiangrass,<br />

[native] bluestems, etc., that were common years ago, before non-native<br />

species such as bermudagrass were introduced,” says Boland. In recent<br />

years many stockman planted or sprigged monocultures of introduced forages<br />

and many native species died out. Yet when cattle have a variety of<br />

plants from which to select, they eat a mixed diet rather than eat only one<br />

type of forage.<br />

“The first year we did this, native grass pastures out-performed the<br />

bermudagrass and the cattle looked good,” Boland says. We are taking a<br />

multi-disciplinary approach with wildlife personnel monitoring nests of<br />

different grassland birds, insect populations, and effects on different pollinator<br />

species. We’re trying to look at it as an ecosystem service as well as<br />

optimizing cattle-growing conditions,” says Boland.<br />

Boland also said it really didn’t matter what proportion of grass or<br />

legume was in the pasture, animals “... consistently ate about 70% of their<br />

diet as legume and 30% as grass.” Even if grass was predominant, they<br />

sought legumes to balance the diet. Planting monocultures or bicultures,<br />

using aggressive introduced grasses and legumes, spraying broadleaf<br />

herbicides, and some grazing systems can jeopardize animal health and<br />

performance, soil health, and wildlife habitat values.<br />

Range conservationists know that animals eat a variety of forbs<br />

in native rangeland, not just legumes. This makes herbicides to control<br />

broadleaves, including legumes, counter-productive as well as expensive<br />

for producers. Given the opportunity, grazing animals will select for a<br />

high quality, healthy diet. While it is true that some native forbs as well<br />

as introduced weeds have toxic properties, animals seldom eat them or<br />

enough to make them sick; or if they do, they will dilute their diet with<br />

other nutritious plants. Drought does cause concerns, however, because<br />

forbs and shrubs may be the only thing still green in many pastures and<br />

starving cattle may eat plants they would not ordinarily eat. Best not to<br />

starve them.<br />

Yours for better grasslands,<br />

Steve Clubine<br />

MDC<br />

Mike Gaskins with the<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> Department<br />

of Conservation standing<br />

between two hay<br />

fields this past July<br />

in Shannon County:<br />

native prairie grasses<br />

and wildflowers on the<br />

left and non-native<br />

cool-season grasses<br />

on the right. Both had<br />

been hayed earlier in<br />

the year.<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 25