The History of Piket Bo Berg JOHN PAULUS EKSTEEN VERSFELD

The History of Piket Bo Berg JOHN PAULUS EKSTEEN VERSFELD

The History of Piket Bo Berg JOHN PAULUS EKSTEEN VERSFELD

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Piket</strong> <strong>Bo</strong> <strong>Berg</strong><br />

<strong>JOHN</strong> <strong>PAULUS</strong> <strong>EKSTEEN</strong> <strong>VERSFELD</strong><br />

To understand the <strong>Piket</strong>berg Mountain properly it is necessary to know the story <strong>of</strong> John Versfeld. So<br />

writes Molly D’Arcy Thompson in her book “Forgotten Corners <strong>of</strong> the Cape” (published in 1979).<br />

<strong>The</strong> amazing structure <strong>of</strong> the Versfeld Pass which John constructed up the steep slopes <strong>of</strong> the Mountain<br />

so that he could easily access the village <strong>of</strong> <strong>Piket</strong>berg from his mountain farm, has ensured that his<br />

name is remembered for posterity.<br />

Apparently John used to sit at the top <strong>of</strong> the mountain, smoking his pipe, and viewing the village<br />

below, contemplating how he could build a road down the steep mountainside so saving the long<br />

journey across the mountain and down the other side at the mission station <strong>of</strong> Goedverwacht and then<br />

round the southern end <strong>of</strong> the mountain - a very long journey in a horse drawn cart! His wife had<br />

given birth to 15 children, and the long haul to the village had meant there had been a few anxious<br />

moments. He also needed to be able to get his produce to the fruit packaging complex and the railway<br />

line if he was to be successful in his farming ventures.<br />

So, the story goes, one night he woke up with the moonlight shining on his watch and chain on his<br />

bedside table. <strong>The</strong> chain was twisted and kinked and looped back on itself. “That’s it!” he cried,<br />

startling his wife, “That is what I will do with my pass!”<br />

In 1889 he began the work, with twenty farm labourers and an overseer. He, simply a farmer, made all<br />

his own measuring instruments and relied entirely on his own commonsense, and so solved the<br />

difficulty <strong>of</strong> the hairpin bends by turning them into loops which doubled back on each other. Every bit<br />

<strong>of</strong> the pass was his own careful work. He set <strong>of</strong>f every morning at dawn on his grey horse “Moscow”,<br />

returning after dark. <strong>The</strong>re was just one day, the day his son Jack was born, when he stayed at home,<br />

and all that day’s work had to be done again as the gradient was too steep. In three months his road<br />

was an accomplished fact just as it stands now, except that it has been widened in the course <strong>of</strong> the<br />

years.<br />

Who, then was John Versfeld? Of Dutch descent, his mother died when he was only two years old<br />

and he went to live with his grandparents in Wynberg. Here he began his schooling, walking three<br />

miles there and back each day. His father remarried, and John left school early to help his father on the<br />

farm Slang Kop in the district <strong>of</strong> Groene Klo<strong>of</strong>, where there was a Moravian Mission.<br />

His claim to fame is that he was a cousin <strong>of</strong> Hildagonda Duckitt, the well-known writer <strong>of</strong> old Cape<br />

recipes. John’s aunt, Hildagonda Versfeld, married Mr. Duckitt <strong>of</strong> Groote Poste farm also in the<br />

Groene Klo<strong>of</strong> district. <strong>The</strong> Duckitts, Versfelds and Melcks were all related.<br />

John left home and the happy, friendly neighbourhood <strong>of</strong> Groene Klo<strong>of</strong> at twenty-four to manage a<br />

farm near Caledon. His father, who had a big second family, was only able to give his eldest son a<br />

horse and a suit <strong>of</strong> clothes, and with these as his sole possessions he went <strong>of</strong>f to make his own way in<br />

the world. While at Caledon John fell in love with Mary Elizabeth Metcalfe, the eldest daughter <strong>of</strong> a<br />

neighbouring farmer. Although Mary had another suitor, the dashing John, with his auburn locks,<br />

wooing her with romantic ballads and dazzling her by vaulting upon his horse, won her hand! <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were married in 1863 when Mary was not yet eighteen and John twenty-five.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y had been married about five years when, in 1867, John bought Langeberg farm up on the<br />

Mountain. He was determined to make a living there, against the advice <strong>of</strong> those who thought they

knew better and warned him that he was bound to fail. He wanted to be his own master; he had saved<br />

a few hundred pounds, he had a flock <strong>of</strong> merino sheep, his faithful shepherd Danje Engelbrecht with<br />

wife and children, besides a farmhand and his wife. “And so, with Mother to stand by him,” said his<br />

daughter Jessie, “(he never did anything without her whole-hearted co-operation,)” he moved there<br />

with his young wife and two little daughters, a wagon and a span <strong>of</strong> mules, horses and a cart.<br />

<strong>The</strong> farmhouse was quite primitive, with mud floors and no ceilings or glass in the windows; the first<br />

night a leopard jumped into the sheep-kraal and carried <strong>of</strong>f a sheep.<br />

When John arrived on the <strong>Piket</strong>berg Mountain the only people making a living there were the Lucas<br />

family, a widow and her four sons, living on a neighbouring farm Tweefontein.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y were industrious and very skilled at growing and making roll tobacco; their Lucas brand was<br />

considered to be the best obtainable, and they retained this reputation until their descendants gave up<br />

tobacco for fruit-growing. <strong>The</strong> Lucas’s taught John this line <strong>of</strong> farming, which he pursued with<br />

success; in his turn he was able to show them the advantage <strong>of</strong> merino sheep farming over the stock<br />

they were keeping.<br />

John’s daughter, Jessie, writes, “When I was born in mid-winter they say I never saw the sun for a<br />

fortnight, and Papa used to ride over to Voorste Vlei in the pouring rain every day to try to save his<br />

lambs, but they all died. It was no wonder that the lonely life began to tell on Mother’s health and<br />

Papa decided that he had been wrong to bring her so far from civilization. He has <strong>of</strong>ten told us how he<br />

had written an advertisement for the farm when Mother came along and made him tear it up and said<br />

she would try again. One <strong>of</strong> her sisters came to stay with her and from that time there was never any<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> giving up.”<br />

Life on the mountain top was hard for the young people. But John found a source <strong>of</strong> help and strength<br />

in the Mission <strong>of</strong> Goedverwacht, which lay deep in the valley below his farms Langeberg and<br />

Voorstevlei. Without the support <strong>of</strong> the Mission they would scarcely have been able to carry on.<br />

Among John Versfeld’a achievements on the mountain was a gravel road he made into Goedverwacht<br />

valley. When he wanted to ride to Malmesbury or Darling where his father lived, he followed the<br />

narrow road he had made along the mountain side, which drops steeply to the valley below, then along<br />

the river to Goedverwacht and out onto the plain. This is the road the Mission folk used to take to join<br />

in social events on the mountain<br />

To get to <strong>Piket</strong>berg village from the mountain top in those days was no easy matter. When a new baby<br />

had to be christened John and Mary took the cart as far as possible, then they rode down the bridlepath,<br />

servants carried the baby and toddlers, and the harness was laid on two spare horses. A cart was<br />

kept at Deze Hoek, where the nearest neighbours <strong>of</strong> their own kind farmed. From Deze Hoek they<br />

drove to <strong>Piket</strong>berg where the Minister, the Magistrate and the Schoolmaster lived – as yet there was no<br />

doctor. Here they could converse with educated people: their mountain neighbours were hardworking,<br />

kindly but illiterate folk.<br />

In 1872 John bought the largest and best farm on the mountain – Moutonsvallei, for £1,000 cash. He<br />

immediately began to build a new, spacious house beside it, and except for one large addition a few<br />

years later, it was much the same until fairly recently. It lies in a sheltered valley, protected by the<br />

mountain behind.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n John began planting trees and fruit trees all over his land. Molly D’Arcy Thompson writes, “A<br />

hundred years earlier, however, somewhere about 1780, an unknown man, perhaps a Mouton, came<br />

into the wilds and planted a wonderful garden. Its boundary fences were dog-rose hedges many feet

high and wide. <strong>The</strong>re were some tall thick-stemmed orange trees, planted in a grove longer than<br />

broad, say about six trees by twelve, and down its length on the north side stood a row <strong>of</strong> mighty pears,<br />

mostly sweet saffron….. On the south side <strong>of</strong> the orange grove was a row <strong>of</strong> walnut trees; there was a<br />

large peach orchard, a dozen or so <strong>of</strong> apricots, two almonds, a few fig trees, two or three apple trees, a<br />

New Year plum, even a nectarine right in the middle <strong>of</strong> the peach orchard – a quince hedge, a<br />

pomegranate hedge, a clump <strong>of</strong> bamboos and a large stretch <strong>of</strong> vineyard. Add to these two mighty<br />

oaks and a row <strong>of</strong> blue-gums and you have a picture <strong>of</strong> the little paradise into which they moved from<br />

Langeberg….”<br />

John continued this valuable work by planting apple trees, French pears from his Uncle at<br />

Classenbosch and quick-growing gums and pine trees to give shade; then finding that his first oak trees<br />

flourished, he started an oak nursery and in due course there were 4 000 oaks in avenues and<br />

plantations. Jessie notes that her Mother and Nurse watered the tiny tree seedlings with her bathwater!<br />

<strong>The</strong> family had fifteen children: there was a governess in the school-room, and later on elder sisters<br />

returned from school and taught the younger children.<br />

John’s youngest son, Walter, was only four when his father died. Moutonsvallei farm was divided<br />

between him and an elder brother, and Walter built a delightful gabled house, Stawel Klip, overlooking<br />

the valley. He farmed on the Mountain for 66 years.<br />

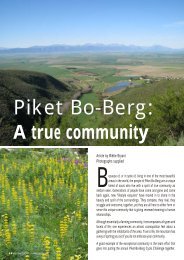

Today the Mountain is an important deciduous-fruit producing district <strong>of</strong> the Cape, as well as growing<br />

buchu, a project started by one <strong>of</strong> John’s sons. This mountain top, where orchards now stretch<br />

wherever there is flat and fertile soil, was weaned from its rugged natural state by the green and loving<br />

fingers <strong>of</strong> John Paulus Eksteen Versfeld.