Fall 2011 - Institute of Medical Science - University of Toronto

Fall 2011 - Institute of Medical Science - University of Toronto

Fall 2011 - Institute of Medical Science - University of Toronto

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SURP RESEARCH FOCUS<br />

Given the rigour <strong>of</strong> their design, are the results<br />

<strong>of</strong> RCTs fool-pro<strong>of</strong>? There are several<br />

examples where the results <strong>of</strong> such trials did<br />

not seem to agree with clinical reality. R<strong>of</strong>ecoxib<br />

is a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor whose<br />

use for the treatment <strong>of</strong> arthritis became<br />

widespread after favourable results from<br />

RCTs, only to be taken <strong>of</strong>f the market a few<br />

years later when it was found to increase the<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular complications 6 . Reboxetine<br />

was touted as an effective anti-depressant<br />

until it was discovered that publication<br />

<strong>of</strong> data had been highly selective – once the<br />

complete body <strong>of</strong> data concerning drug efficacy<br />

and safety were evaluated, it was found<br />

that the drug was not only ineffective in the<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> depression, but harmful 7 .<br />

In the above examples, the reported results<br />

<strong>of</strong> RCTs did not correspond with reality because<br />

<strong>of</strong> bias in trial conduct, analysis, or<br />

publication 6,8 . Unfortunately, the degree to<br />

which this sort <strong>of</strong> bias affects the published<br />

results <strong>of</strong> any RCT is unknown.<br />

Methods to evaluate bias in RCTs are important<br />

for physicians who use results <strong>of</strong> RCTs<br />

to guide treatment decisions. There is no<br />

objective gold standard to evaluate bias because<br />

it is difficult to measure and can only<br />

be estimated 9 . An optimal assessment <strong>of</strong> bias<br />

requires unrestricted access to both the procedures<br />

used by the trial researchers and the<br />

complete raw data, but such access is very<br />

difficult to attain 10 . Nevertheless, there are<br />

Adverse<br />

Event<br />

Not in results<br />

table (NOT R)<br />

In results table<br />

(R)<br />

Not in abstract<br />

(NOT A)<br />

In Abstract (A)<br />

Not in discussion<br />

(NOT D)<br />

In discussion<br />

(D)<br />

Not in concluding<br />

statement<br />

(NOT C)<br />

In concluding<br />

statement (C)<br />

certain criteria that can be used to estimate<br />

the degree <strong>of</strong> bias in RCTs.<br />

One criterion used to assess bias is the systematic<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> the reporting <strong>of</strong> trial<br />

endpoints. Endpoints are outcomes being<br />

measured by the trial, which may include<br />

overall survival, disease-free survival, quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> life and response rate, among others. RCTs<br />

are designed to recruit a predefined number<br />

<strong>of</strong> people, and to determine if a statistically<br />

significant difference in primary endpoints<br />

exists 9 . This does not mean that significant<br />

differences in other endpoints are not important,<br />

but statistical tests applied to them are<br />

subject to misinterpretation 8 . The evaluation<br />

<strong>of</strong> secondary endpoints should therefore be<br />

regarded as exploratory. If a publication does<br />

not clearly indicate the results relating to the<br />

primary endpoint <strong>of</strong> the trial and does not<br />

describe the results <strong>of</strong> secondary endpoints<br />

in its concluding statements, it is biased 8 .<br />

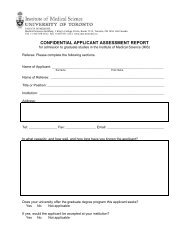

Another possible criterion for the systematic<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> bias is the reporting <strong>of</strong> adverse<br />

events (AEs) associated with the experimental<br />

treatment. We developed a method to<br />

evaluate this bias, which employed a hierarchy<br />

<strong>of</strong> AE reporting based on the sections <strong>of</strong><br />

a publication where AEs are most likely to be<br />

read (Figure 1).<br />

In each <strong>of</strong> 168 publications <strong>of</strong> RCTs evaluating<br />

breast cancer treatment, every reported<br />

moderate to severe AE that was statistically<br />

Not in<br />

discussion<br />

(NOT D)<br />

In discussion<br />

(D)<br />

Not in<br />

discussion<br />

(NOT D)<br />

In discussion<br />

(D)<br />

NOT R<br />

R + (NOT A) +<br />

(NOT D)<br />

R + (NOT A) + D<br />

R + A + (NOT C) +<br />

(NOT D)<br />

R + A + (NOT C) +<br />

D<br />

R + A + C +<br />

(NOT D)<br />

R + A + C + D<br />

Inadequate<br />

reporting <strong>of</strong><br />

adverse events<br />

Less adequate<br />

reporting <strong>of</strong><br />

adverse events<br />

Adequate<br />

reporting <strong>of</strong><br />

adverse events<br />

Figure 1. Hierarchy <strong>of</strong> adverse events (AE) reporting. One possible hierarchy scheme is shown, where<br />

the top represents the least adequate reporting <strong>of</strong> a moderate to severe AE.<br />

different between the experimental and control<br />

arms received a score based on its position<br />

in the hierarchy. This score was used to<br />

cluster publications that had a similar reporting<br />

<strong>of</strong> AEs. With a large enough sample <strong>of</strong><br />

publications, individual clusters could be defined<br />

where each represents a certain degree<br />

<strong>of</strong> bias. A survey querying oncologists about<br />

where they most commonly see the reporting<br />

<strong>of</strong> AEs in publications <strong>of</strong> RCTs has been designed<br />

to test the validation <strong>of</strong> the hierarchy<br />

in Figure 1. The results are pending.<br />

There is substantial evidence that bias exists<br />

in the conduct, analysis, and reporting<br />

<strong>of</strong> RCTs 8-10 . A measure <strong>of</strong> the degree <strong>of</strong> this<br />

bias would be <strong>of</strong> great help to those who must<br />

decide how much to trust the results <strong>of</strong> these<br />

RCTs, especially when deciding whether<br />

to apply the results to patients. Although<br />

no gold standard exists that can be used to<br />

evaluate the degree <strong>of</strong> bias in a publication,<br />

methods are being developed for the purpose<br />

<strong>of</strong> estimating this bias with the hope <strong>of</strong> minimizing<br />

its effect on clinical decision-making.<br />

References<br />

1. Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized controlled<br />

trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy <strong>of</strong><br />

research designs. NEJM 2000; 342(25): 1887-92.<br />

2. FDA approval <strong>of</strong> new cancer treatment uses for marketed<br />

drug and biological products. Food and Drug<br />

Administration; c1998. Available from: http://www.fda.<br />

gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071657.pdf<br />

(accessed<br />

August <strong>2011</strong>)<br />

3. Altman DG, Bland JM. How to randomize. BMJ 1999;<br />

319: 703-4.<br />

4. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in<br />

randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet<br />

2002; 359: 614-8.<br />

5. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials:<br />

hiding who got what. Lancet 2002; 359: 696-700.<br />

6. Roth-Cline MD. Clinical trials in the wake <strong>of</strong> Vioxx.<br />

Circulation 2006; 113: 2253-59.<br />

7. Eyding D, Lelgemann M, Grouven U, Harter M,<br />

Kromp M, Kaiser T, Kerekes MF, Gerken M, Wieseler<br />

B. Reboxetine for acute treatment <strong>of</strong> major depression:<br />

systematic review and meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> published<br />

and unpublished placebo and selective serotonin reuptake<br />

inhibitor controlled trials. BMJ 2010; 341: c4737<br />

doi:10.1136/bmj.c4737<br />

8. Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting<br />

and interpretation <strong>of</strong> randomized controlled trials<br />

with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes.<br />

JAMA 2010; 303(20): 2058-64.<br />

9. Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gotzsche PC,<br />

Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting<br />

<strong>of</strong> outcomes in randomized trials. JAMA 2004; 291(20):<br />

2457-65.<br />

10. Chan AW. Bias, spin, and misreporting: time for<br />

full access to trial protocols and results. PLoS Medicine<br />

2008; 5(11): 1533-35.<br />

IMS MAGAZINE FALL <strong>2011</strong> PROSTATE CANCER | 30