The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European art of the ...

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European art of the ...

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European art of the ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

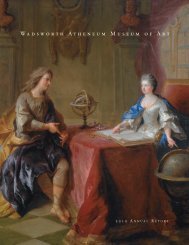

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pleasure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong><strong>European</strong> <strong>art</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century increasingly emphasized civility, elegance, comfort, <strong>and</strong>informality. During <strong>the</strong> first half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> century, <strong>the</strong> Rococo style <strong>of</strong> <strong>art</strong> <strong>and</strong> decoration,characterized by lightness, grace, playfulness, <strong>and</strong> intimacy, spread throughout Europe. Paintersturned to ligh<strong>the</strong><strong>art</strong>ed subjects, including inventive pastoral l<strong>and</strong>scapes, scenic vistas <strong>of</strong> popul<strong>art</strong>ourist sites, <strong>and</strong> genre subjects—scenes <strong>of</strong> everyday life. Mythology became a vehicle for <strong>the</strong>expression <strong>of</strong> pleasure ra<strong>the</strong>r than a means <strong>of</strong> revealing hidden truths. Porcelain <strong>and</strong> silvermakers designed exuberant fantasies for use or as pure decoration to complement newlyremodeled interiors conducive to entertainment <strong>and</strong> pleasure.As <strong>the</strong> century progressed, <strong>art</strong>ists increasingly adopted more serious subject matter, <strong>of</strong>ten takenfrom classical history, <strong>and</strong> a simpler, less decorative style. This was <strong>the</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong>,when writers <strong>and</strong> philosophers came to believe that moral, intellectual, <strong>and</strong> social reform waspossible through <strong>the</strong> acquisition <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> reason. <strong>The</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Tour, ameans <strong>of</strong> personal enlightenment <strong>and</strong> an essential element <strong>of</strong> an upper-class education, wassymbolic <strong>of</strong> this age <strong>of</strong> reason.<strong>The</strong> installation highlights <strong>the</strong> museum’s rich collection <strong>of</strong> eighteenth-century paintings <strong>and</strong>decorative <strong>art</strong>s. It is organized around four <strong>the</strong>mes: Myth <strong>and</strong> Religion, Patrons <strong>and</strong> Collectors,Everyday Life, <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong> Natural World. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>the</strong>mes are common to <strong>art</strong> from different cultures<strong>and</strong> eras, <strong>and</strong> reveal connections among <strong>the</strong> many ways <strong>art</strong>ists have visually expressed <strong>the</strong>ircultural, spiritual, political, material, <strong>and</strong> social values.

Domenico CorviItalian, Roman, 1721–1803<strong>The</strong> Miracle <strong>of</strong> St. Joseph Calasanz Resuscitating a Child in a Church at Frascati, 1767Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1981.24<strong>The</strong> Spanish saint, Joseph Calasanz (1558–1648) was canonized in 1767, <strong>the</strong> same year hisfollowers, known as Scolopians or Piarists, presented this altarpiece to Pope Clement XIII.Devoted to education, especially <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> homeless <strong>and</strong> neglected, Joseph Calasanz went to Romein 1592, <strong>and</strong> founded a free school for poor children <strong>the</strong>re five years later.Corvi’s painting encourages <strong>the</strong> emotional involvement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> observer by presenting <strong>the</strong> sacreddrama in a convincing narrative manner. <strong>The</strong> saint kneels before an altar adorned with a largepicture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Virgin <strong>and</strong> Child, <strong>and</strong> appeals to <strong>the</strong> Madonna to revive <strong>the</strong> dead child in his arms,as <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r looks on. A Scolopian fa<strong>the</strong>r enters <strong>the</strong> scene with his pupils, <strong>the</strong>ir animatedgestures <strong>and</strong> facial expressions injecting energy <strong>and</strong> emotion into <strong>the</strong> scene.Carle Van LooFrench, 1705–1765Offering to Cupid, 1761Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1979.186Offering to Cupid reflects <strong>the</strong> fascination with antiquity—fueled by excavations <strong>of</strong> ancient sitesin Italy—that swept mid-eighteenth-century France, influencing all aspects <strong>of</strong> culture <strong>and</strong>fashion. <strong>The</strong> subject is a contemporary interpretation <strong>of</strong> an ancient rite, in which a young maidenmakes an <strong>of</strong>fering to Cupid, <strong>the</strong> god <strong>of</strong> love. <strong>The</strong> elongated figures <strong>and</strong> sheer, clinging draperyrecall ancient Greek paintings <strong>and</strong> statues. But <strong>the</strong> fea<strong>the</strong>ry brushstrokes <strong>and</strong> pastel colors reflect<strong>the</strong> decorative Rococo style <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century, marking Offering to Cupid as a work inwhich old <strong>and</strong> new elements combine.Carle Van Loo, <strong>the</strong> most famous member <strong>of</strong> a family <strong>of</strong> painters <strong>and</strong> <strong>art</strong>ists, was trained in bothParis <strong>and</strong> Rome, <strong>and</strong> known for his ability to paint a range <strong>of</strong> subjects <strong>and</strong> styles. By <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong>his death in 1765, he had been ennobled <strong>and</strong> appointed Premier Painter to <strong>the</strong> King, Louis XV.

Attributed to Johan RichterSwedish (active in Venice), 1665–1745Feast <strong>of</strong> Santa Maria della Salute, c. 1720Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1939.268Feast <strong>of</strong> Santa Maria della Salute depicts <strong>the</strong> Festival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Presentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Virgin, whichtook place annually in Venice on November 21, when a bridge <strong>of</strong> boats would be constructedacross <strong>the</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Canal, connecting <strong>the</strong> Church <strong>of</strong> Santa Maria della Salute with <strong>the</strong> Church <strong>of</strong>Santa Maria del Giglio. <strong>The</strong> Doge <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Elders <strong>of</strong> Venice would pass in procession across <strong>the</strong>bridge to celebrate <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Church <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Salute. Conceived in 1630 to payhomage to <strong>the</strong> Virgin Mary for delivering Venice from <strong>the</strong> plague that year, it was begun in 1631<strong>and</strong> completed fifty years later.This painting has recently been attributed to Johan Richter, a Swedish <strong>art</strong>ist who worked inVenice from at least 1717. Richter, along with Luca Carlevarijs—to whom this painting has alsobeen attributed—was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two painters who specialized in views <strong>of</strong> Venice beforeCanaletto, whose work is seen in <strong>the</strong> next gallery.CASECupid (L’Amour de Falconet)Sèvres, 1762, base 1777Perhaps François-Joseph Aloncle (painter, active 1758–81) <strong>and</strong> Jean-Pierre Boulanger (gilder,active 1754–85)S<strong>of</strong>t-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.959Falconet’s Cupid—first produced in 1758 <strong>and</strong> modeled on his marble version for <strong>the</strong> king’smistress, Madame de Pompadour—gestures <strong>the</strong> onlooker to be silent, presumably so that he canshoot his victim unaware. In type he is a fusion <strong>of</strong> two Greek deities, Harpocrates, <strong>the</strong> god <strong>of</strong>silence, <strong>and</strong> Cupid, <strong>the</strong> god <strong>of</strong> love. Harpocrates was represented as an infant with his finger heldto his mouth, while Cupid was commonly portrayed with wings <strong>and</strong> a bow, quiver, <strong>and</strong> arrows.“Psyche” (Pendant de L’Amour de Falconet)Sèvres, c. 1761–73; pedestal 1777François-Joseph Aloncle (painter, active 1758–81) <strong>and</strong> Jean-Pierre Boulanger (gilder, active1754–84)S<strong>of</strong>t-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.960This model was originally introduced into production in 1761, having been created by Falconetspecifically as a pendant to his Cupid <strong>of</strong> 1758. <strong>The</strong> base is inscribed with a quote from Virgil'sEcologues, “Et nos cedamus amori” (let us yield to love). Although Psyche was Cupid’s lover inmythology, this figure was never called Psyche by <strong>the</strong> Sèvres factory. Hundreds <strong>of</strong> examples <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se figures were sold in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century.

Everyday LifeArt, both decorative <strong>and</strong> functional, has always been made for <strong>the</strong> domestic environment.Everyday life, both high <strong>and</strong> low, has also provided subject matter for <strong>art</strong>ists. Works <strong>of</strong> <strong>art</strong> can<strong>of</strong>fer a window into everyday life by recording private moments, social customs, domesticinteriors, <strong>and</strong> changing fashion, across time <strong>and</strong> geography.Gaspare TraversiItalian, Neapolitan, c. 1722–1770A Quarrel over a Board Game, c. 1752Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1948.118Tavern scenes such as this one, showing games <strong>and</strong> gambling, were <strong>of</strong>ten intended to conveymoralizing messages denouncing human weakness. This work focuses on a range <strong>of</strong> emotions—concern, fear, <strong>and</strong> anger—made emphatic by <strong>the</strong> placement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three-qu<strong>art</strong>er-length figures ina narrow foreground space. Traversi also delighted in painting rich colors <strong>and</strong> fabrics, seen mostespecially in <strong>the</strong> embroidery on <strong>the</strong> waistcoat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> man on <strong>the</strong> left. <strong>The</strong> overall impression isone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>atricality <strong>and</strong> stylish staging, suggesting that <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist may have been inspired bycontemporary <strong>the</strong>ater or opera.Traversi began his career in Naples but in 1752 moved to Rome where he remained until hisdeath. His most significant contributions to eighteenth-century Italian painting are his eloquent<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten mocking reflections on <strong>the</strong> morals <strong>of</strong> his time.Pietro LonghiItalian, 1702–1785<strong>The</strong> Temptation, c. 1745Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1931.188Longhi was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most gifted <strong>of</strong> eighteenth-century genre painters in Venice, an excellentdraughtsman who effortlessly captured <strong>the</strong> features <strong>and</strong> gestures <strong>of</strong> his subjects. He depicteddelightful scenes, <strong>of</strong>ten satirical, <strong>of</strong> life among <strong>the</strong> city's upper classes. In this work a youngmonk visits a group <strong>of</strong> ladies engaged in sewing <strong>and</strong> holds a glass to his eye to get a betterlook—though not necessarily at <strong>the</strong>ir work. <strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> caged bird is undoubtedly areference to <strong>the</strong> preservation <strong>of</strong> virtue, as a bird in a cage symbolizes intact virginity.

Unidentified ArtistEnglish, 18th centuryPortrait <strong>of</strong> Two Ladies, c. 1765Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1945.353Portrait <strong>of</strong> Two Ladies is an excellent example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> popular English Conversation picture,which typically depicts real people in <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ordinary daily activities, in this casereading <strong>and</strong> sewing. This type <strong>of</strong> domestic genre scene appealed to new middle-class patrons asan alternative to <strong>the</strong> more <strong>art</strong>ificial, formally posed portrait.Giuseppe Maria CrespiItalian, Bolognese, 1665–1747An Artist in his Studio, 1730sOil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1936.499Crespi was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first Italian painters <strong>of</strong> note to devote serious attention to <strong>the</strong> depiction <strong>of</strong>contemporary life. In this picture, genre <strong>and</strong> portraiture are united, producing an intimate lookinto <strong>the</strong> domestic surroundings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist. At his easel, he is surrounded by <strong>the</strong> accoutrements<strong>of</strong> his pr<strong>of</strong>ession, including casts <strong>of</strong> faces <strong>and</strong> body p<strong>art</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> Crespi’s own copy <strong>of</strong> a painting by<strong>the</strong> seventeenth-century <strong>art</strong>ist Giovanni Francesco Barberi, known as Guercino.This is probably a self-portrait, painted by Crespi late in life, but depicting himself as a youngerman. It has also been proposed that <strong>the</strong> painting could be a portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist's son, Luigi, whowas also a painter.Giacomo CerutiItalian, Milanese, 1698–1767Girl with a Dove, c. 1730–40Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1942.352Girl with a Dove exemplifies Ceruti’s work as a painter <strong>of</strong> genre <strong>and</strong> portraits, <strong>and</strong> in this picturehe combines elements from both types. It is a portrait not <strong>of</strong> a middle or upper class woman, but<strong>of</strong> a peasant girl, a subject usually reserved for genre scenes. <strong>The</strong> informal realism <strong>and</strong> frankness<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pose, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dove, are well suited to <strong>the</strong> sitter <strong>and</strong> characteristic <strong>of</strong>Ceruti’s work.

Giovanni Battista PiazzettaItalian, Venetian, 1683–1754Boy with a Pear, c. 1740Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1944.34<strong>and</strong>Girl with a Ring Biscuit, c. 1740Oil on canvasPurchased in honor <strong>of</strong> Jean K. Cadogan with funds raised, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> MaryCatlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1997.22.1Throughout his career, <strong>the</strong> Venetian painter Piazzetta produced half-length figures such as thisboy <strong>and</strong> girl. <strong>The</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> this pair is <strong>the</strong> interchange between <strong>the</strong> hopeful youth <strong>of</strong>fering hisfruit, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> young lady who seems to discourage his advances. In fact <strong>the</strong>se paintings probablyillustrate popular eighteenth-century Italian idioms. <strong>The</strong> phrase “cascare come pera cotta” (“t<strong>of</strong>all like a cooked pear”) meant to fall in love, while <strong>the</strong> proverb “Non tutte le ciambelle riesconocon buco” (“not all ring biscuits are made with holes”) implied that all does not turn out well.Attributed to Charles Joseph Flip<strong>art</strong>French, 1721–1797Portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Castrato Carlo Scalzi, c. 1738Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1938.177Opera flourished in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century, <strong>and</strong> was performed all over Europe, both in privatecourt <strong>the</strong>aters <strong>and</strong> later in large public opera houses. As <strong>the</strong> audience for opera exp<strong>and</strong>ed, light orcomic operas, which came from humble beginnings, began to flourish alongside serious or tragicopera.This portrait is thought to represent <strong>the</strong> eighteenth-century Italian opera singer Carlo Scalzi, one<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most famous male sopranos or castrati. It has been debated whe<strong>the</strong>r Signor Scalzi isrepresented here as a character from Leonardo Vinci's opera Artaserse (1730–31) or from NicoloPopora's Sirbace (1737). In ei<strong>the</strong>r case, his costume is a <strong>European</strong> interpretation <strong>of</strong> Persian dress,very much an eighteenth-century operatic fantasy.

CASE LABELBirdcageGerman, Meissen, 1740–50Hard-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.1247Birdcages in Meissen porcelain are extremely rare, as <strong>the</strong>y would have been difficult to make<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore very costly. A solid form was made first, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n carved out by h<strong>and</strong> to form <strong>the</strong>reticulated shape. Next small forget-me-not flowers were applied <strong>and</strong> painted. It is remarkablethat this large, pierced cage did not collapse in <strong>the</strong> kiln.While pet birds were kept in many well-to-do households in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century, to have aporcelain birdcage must have been <strong>the</strong> height <strong>of</strong> luxury.CASEHerring DishDutch, Delft, c. 1700De Dissel (<strong>The</strong> Pole factory, 1640–1701)Tin-glazed e<strong>art</strong>henware<strong>The</strong> Richard <strong>and</strong> Georgette A. Koopman Collection <strong>of</strong> Delft, 2004.26.26Herring was p<strong>art</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fabric <strong>of</strong> daily life in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rl<strong>and</strong>s. A Dutch proverb goes "Haring in'tl<strong>and</strong>, dokter aan de kant," meaning "If herring is around, <strong>the</strong> doctor is far away." <strong>The</strong> catch wassold by vendors who pushed <strong>the</strong>ir products through <strong>the</strong> streets in two-wheeled c<strong>art</strong>s. <strong>The</strong> herringwas boned, <strong>and</strong> eaten raw, smoked, or salted. Most households had a special dish in which toserve it.Cheese Vendor PlateDutch, Delft, mid-18th centuryTin-glazed e<strong>art</strong>henware<strong>The</strong> Richard <strong>and</strong> Georgette A. Koopman Collection <strong>of</strong> Delft, 2004.26.9Though milk was plentiful in Holl<strong>and</strong>, it was also perishable <strong>and</strong> thus frequently made intocheese. Both cow’s <strong>and</strong> sheep’s milk were used. Cheese was usually named for <strong>the</strong> place whereit originated; <strong>the</strong> Dutch are still famous for cheeses like Gouda <strong>and</strong> Edam. This plate, used toserve cheese, also depicts how cheese was sold in shops in Holl<strong>and</strong>.

Butter TubDutch, Delft, c. 1760Tin-glazed e<strong>art</strong>henware<strong>The</strong> Richard <strong>and</strong> Georgette A. Koopman Collection <strong>of</strong> Delft, 2004.26.56A,BButter tubs were found on almost every table in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rl<strong>and</strong>s, where bread <strong>and</strong> butter wereeaten in great quantity. <strong>The</strong> shape <strong>of</strong> this tub developed from wooden utensils that had lids heldin place by two rods. In <strong>the</strong> ceramic tubs, <strong>the</strong> rods were eliminated but <strong>the</strong> leaf-form h<strong>and</strong>lesretained <strong>the</strong> holes never<strong>the</strong>less.Charles-Antoine CoypelFrench, 1694–1752<strong>The</strong> Fainting <strong>of</strong> Armida, c. 1733–35Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 2011.5.1Coypel began his career as a designer <strong>of</strong> tapestries for <strong>the</strong> Gobelins factory, <strong>and</strong> soon became <strong>the</strong>favorite painter <strong>of</strong> Maria Leczinska, Louis XV’s Polish-born queen. He was also greatly inspiredby <strong>the</strong>ater <strong>and</strong> opera, <strong>and</strong> he even began a second career as a playwright in 1718, producing bothcomedies <strong>and</strong> tragedies. Both aspects <strong>of</strong> his career are reflected in this painting, which may havebeen a preliminary design for a tapestry from <strong>the</strong> Tapestry <strong>of</strong> Operatic Episodes series woven in1771. It illustrates a final scene from <strong>the</strong> popular French opera Armide, in which <strong>the</strong> sorceressArmida, realizing that <strong>the</strong> spell she had cast upon <strong>the</strong> Crusader Rinaldo was broken, prepares todestroy <strong>the</strong> enchanted kingdom she had created. Coypel lavished all his considerable skill onpresenting an extravagant imaginary setting <strong>and</strong> elaborate costumes that present an ideal ra<strong>the</strong>rthan an actual performance.

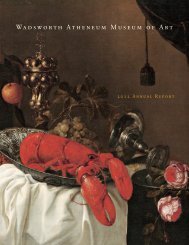

<strong>The</strong> Natural WorldArtists have been exploring <strong>and</strong> chronicling nature since <strong>the</strong> earliest time, depicting <strong>the</strong>l<strong>and</strong>scape with its flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, <strong>and</strong> addressing <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> man’s place in nature. Nature alsoinspires still-life painters <strong>and</strong> is an enduring source <strong>of</strong> motifs for <strong>art</strong>ists <strong>and</strong> designers.Bernardo BellottoItalian, Venetian, 1721–1780View <strong>of</strong> Pirna in Saxony, 1763Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1931.280Bellotto was <strong>the</strong> nephew <strong>and</strong> only pupil <strong>of</strong> Canaletto, who is best known for his scenes <strong>of</strong>Venice. Bellotto worked <strong>the</strong>re with his uncle until 1747, when he left for desirable posts at <strong>the</strong>courts in Munich, Dresden, Vienna, <strong>and</strong> Warsaw. <strong>The</strong> View <strong>of</strong> Pirna in Saxony was paintedduring one <strong>of</strong> Bellotto's stays in Dresden. <strong>The</strong> town <strong>of</strong> Pirna <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Castle <strong>of</strong> Sonnenstein areseen from a hill, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> river Elbe is visible in <strong>the</strong> distance. This detailed rendering <strong>of</strong>topography is typical <strong>of</strong> Bellotto, as are <strong>the</strong> cool colors, intense clear light, <strong>and</strong> rich shadows.Thomas GainsboroughEnglish, 1727–1788Woody L<strong>and</strong>scape, c. 1783–84Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1957.15Although Gainsborough was most famous as a portrait painter in eighteenth-century Engl<strong>and</strong>, histrue love was l<strong>and</strong>scape painting; he just could not make a satisfactory living from it. His chiefinspiration was Dutch seventeenth-century l<strong>and</strong>scapes, which he adapted to fashion his ownidealized views <strong>of</strong> his native Suffolk, as is evidenced here. <strong>The</strong> silvery light that breaks through<strong>the</strong> clouds, <strong>the</strong> fea<strong>the</strong>ry brushwork, <strong>and</strong> intertwined foliage in muted colors all combine to createa nostalgic dream world <strong>of</strong> harmonious relationships between man <strong>and</strong> nature.

Jean-Baptiste de RoyFlemish, 1759–1839L<strong>and</strong>scape with Cattle <strong>and</strong> Cottage, 1796Oil on panelGift <strong>of</strong> Mr. <strong>and</strong> Mrs. James Lippincott Goodwin, 1963.2Jean-Baptiste de RoyFlemish, 1759–1839L<strong>and</strong>scape with Cattle Crossing a Bridge, 1796Oil on panelGift <strong>of</strong> Mr. <strong>and</strong> Mrs. James Lippincott Goodwin, 1963.3Jean-Baptiste de Roy, called de Roy <strong>of</strong> Brussels, was a self-taught painter <strong>and</strong> etcher specializingin l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> pictures <strong>of</strong> animals. When quite young he went to Holl<strong>and</strong> with his fa<strong>the</strong>r.While <strong>the</strong>re he studied <strong>the</strong> Dutch l<strong>and</strong>scape painters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> seventeenth century, who hadsignificantly raised <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape from mere setting to <strong>the</strong> subject matter. It was also <strong>the</strong>re tha<strong>the</strong> created <strong>the</strong>se charming <strong>and</strong> idyllic views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dutch countryside.Giovanni Antonio Canal, called CanalettoItalian, Venetian, 1697–1768L<strong>and</strong>scape with Ruins, c. 1721–22Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1939.290This architectural fantasy, L<strong>and</strong>scape with Ruins is p<strong>art</strong> <strong>of</strong> a larger group <strong>of</strong> imaginary viewpaintings, called capriccio, that have been attributed to <strong>the</strong> young Canaletto. <strong>The</strong> capricciocombined invented <strong>and</strong>/or real architectural features, intact or ruined, in a picturesque setting. Itwas one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more popular types <strong>of</strong> painting during <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Tour <strong>of</strong> Europe, when<strong>the</strong>re was a heavy dem<strong>and</strong> for pictorial souvenirs. In Italy, where <strong>the</strong>re were countless reallocations with Classical ruins, <strong>art</strong>ists only had to use poetic license to combine <strong>and</strong> elaborate onexisting monuments, <strong>and</strong> place <strong>the</strong>m within an idyllic setting.

Luis Egidio MeléndezSpanish, 1716–1780Still Life with Pigeons, Onions, Bread, <strong>and</strong> Kitchen Utensils, c. 1772Oil on canvas<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1938.256An e<strong>art</strong>henware jug, a copper bowl, onions, garlic, bread, <strong>and</strong> a pigeon would be <strong>the</strong> ingredientsfor a humble meal, but Meléndez has arranged <strong>the</strong>m with sensitivity, brilliantly using light todescribe <strong>the</strong>ir varied colors <strong>and</strong> textures. With flawless technique <strong>the</strong> <strong>art</strong>ist produced adistinctive realism with powerfully modeled objects against neutral backgrounds, viewed closeupfrom a low vantage point.Meléndez was an acknowledged master <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> still life, <strong>and</strong> painted more than one hundred <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>m between 1759 <strong>and</strong> 1778.Charles-François Grenier de La Croix, called Lacroix de MarseilleFrench, c. 1700–1782Seascape with a Ruined Arch, 1780Oil on copperGift <strong>of</strong> Mary Batterson Beach, 1946.89Lacroix produced countless modest coastal scenes, all imaginary. This seascape, which is notstrictly a topographical representation, strongly suggests sites on <strong>the</strong> itinerary <strong>of</strong> many a travelerthrough Italy, where Lacroix had spent time in <strong>the</strong> 1750s: <strong>the</strong> hills <strong>and</strong> cascades <strong>of</strong> Tivoli; <strong>the</strong>harbor, lighthouses, <strong>and</strong> old fortresses <strong>of</strong> Naples; or <strong>the</strong> undeveloped coastline near Naples <strong>and</strong>Rome.CASEPair <strong>of</strong> Vases (urnes duplessis)French, Vincennes, 1749–51S<strong>of</strong>t-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.977–.978Flowers adorned decorative objects <strong>of</strong> all types in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century. <strong>The</strong> Vincennesporcelain factory, predecessor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sèvres porcelain factory, embraced <strong>the</strong> taste for floralornamentation with enthusiasm. In this pair <strong>of</strong> vases, flowers sculpted out <strong>of</strong> porcelain—bywomen employed in a specialized workshop for <strong>the</strong> factory—were applied to <strong>the</strong> vases,seeming to grow naturally from <strong>the</strong> feet toward <strong>the</strong> entwined branch h<strong>and</strong>les.

CASETea Kettle <strong>and</strong> St<strong>and</strong>English, London, 1758–59Samuel Courtauld I, active from 1747, died 1765Silver, wood<strong>The</strong> Elizabeth B. Miles Collection <strong>of</strong> English Silver, 1979.45This kettle is decorated with flowers <strong>and</strong> scrolls on <strong>the</strong> body, a cast flower finial, a shell-likeornament on <strong>the</strong> spout, <strong>and</strong> a st<strong>and</strong> with grape vines <strong>and</strong> shell feet. Such nature-based decorationwas a hallmark <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rococo style that swept Europe in <strong>the</strong> middle decades <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eighteenthcentury.<strong>The</strong> H<strong>and</strong> KissGerman, Meissen, c. 1738Model by Johann Joachim KaendlerHard-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.1498Images <strong>of</strong> figures living as simple shepherds in bucolic, l<strong>and</strong>scape settings abound in literature,<strong>the</strong>ater, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual <strong>art</strong>s. This idealized depiction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural world is echoed in porcelainfigures such as <strong>the</strong>se shepherds <strong>and</strong> lovers.Tea Set (déjeuner à baguettes)French, Sèvres, 1776Decorated by Guillaume Noël, active 1755–1800S<strong>of</strong>t-paste porcelainGift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.1090–.1094Tea (as well as c<strong>of</strong>fee <strong>and</strong> chocolate) was consumed in bedrooms, boudoirs, salons, gardens, <strong>and</strong>in <strong>the</strong> bath, <strong>and</strong> was taken at breakfast time <strong>and</strong> at formal receptions. Teapots usually were small,as <strong>the</strong>y were meant to hold very strong tea that would be diluted with boiling water served from ametal kettle.

IN THE CENTER GALLERY<strong>The</strong> Natural World: American Artists Confront <strong>the</strong> SeaIn <strong>the</strong> adjacent galleries, a selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Museum’s extensive collection <strong>of</strong> eighteenth-century<strong>European</strong> paintings <strong>and</strong> decorative <strong>art</strong>s is organized around four <strong>the</strong>mes: Myth <strong>and</strong> Religion,Patrons <strong>and</strong> Collectors, Everyday Life, <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong> Natural World. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>the</strong>mes are common to <strong>art</strong>from different cultures <strong>and</strong> eras.By way <strong>of</strong> comparison with <strong>European</strong> works <strong>of</strong> <strong>art</strong>, this gallery brings toge<strong>the</strong>r American worksspanning 100 years, from <strong>the</strong> late-nineteenth to <strong>the</strong> late-twentieth century. In all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>art</strong>istsconfront <strong>the</strong> sea, an enduring source <strong>of</strong> fascination. As you look at <strong>the</strong>se works, think about how<strong>art</strong>ists throughout history have explored, visually recorded, <strong>and</strong> questioned humanity’s changingrelationship to <strong>the</strong> natural world.Winslow HomerAmerican, 1836–1910Boy in a Dory, c. 1881Watercolor on paperBequest <strong>of</strong> Charles C. Cunningham, 1980.6Joseph CornellAmerican, 1903–1972Untitled, c. 1955Mixed mediaGift <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Joseph <strong>and</strong> Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, 2002.35.6Max ErnstAmerican, born Germany, 1891–1976<strong>The</strong> SunOil, graphite, conté crayon, <strong>and</strong> tempera on card stock<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1933.472Triton with Hippocampi, c. 1946–47American, Corning, New YorkManufactured by Steuben Glass, a division <strong>of</strong> Corning Glass WorksDesigned by Frederick Carder (American, born Engl<strong>and</strong>, 1863–1963)Cast lead glassEdith Olcott Van Gerbig Collection, by exchange, 1972.91Jonathan Bor<strong>of</strong>skyAmerican, born 1942Half a Sailboat Painting at 2.924.773,1984Acrylic on Masonite<strong>The</strong> Ella Gallup Sumner <strong>and</strong> Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1986.47