A Perfect Storm in the Amazon Wilderness - Philip M. Fearnside

A Perfect Storm in the Amazon Wilderness - Philip M. Fearnside

A Perfect Storm in the Amazon Wilderness - Philip M. Fearnside

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

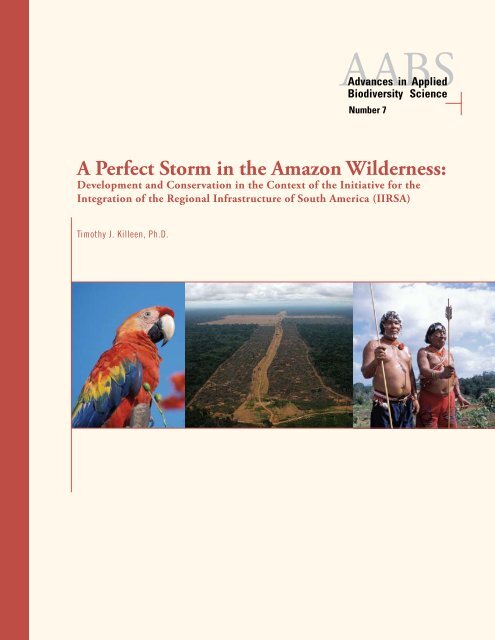

AABSAdvances <strong>in</strong> AppliedBiodiversity ScienceNumber 7A <strong>Perfect</strong> <strong>Storm</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>:Development and Conservation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Context of <strong>the</strong> Initiative for <strong>the</strong>Integration of <strong>the</strong> Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA)Timothy J. Killeen, Ph.D.

Front cover photo credits:[left] John Mart<strong>in</strong>/CI[center] Greenpeace[right] John Mart<strong>in</strong>/CI

A <strong>Perfect</strong> <strong>Storm</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>:Development and Conservation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Context of <strong>the</strong>Initiative for <strong>the</strong> Integration of <strong>the</strong> Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA)Timothy J. Killeen, Ph.D.

The Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity Science series is published by:Center for Applied Biodiversity Science (CABS)Conservation International2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA 22202(703) 341-2718 (tel.)(703) 979-0953 (fax)CI on <strong>the</strong> Web: www.conservation.orgCABS on <strong>the</strong> Web: www.biodiversityscience.orgEditorial: Suzanne ZweizigDesign: Glenda P. FábregasISBN: 978-1-934151-07-5© 2007 by Conservation International. All rights reserved.Pr<strong>in</strong>ted on recycled paper.Conservation International is a private, non-profit organizations exempt from federal <strong>in</strong>come tax under section501 c(3) of <strong>the</strong> Internal Revenue Code.The designations of geographical entities <strong>in</strong> this publication, and <strong>the</strong> presentation of <strong>the</strong> material, do not imply<strong>the</strong> expression of any op<strong>in</strong>ion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part of Conservation International or its support<strong>in</strong>g organizationsconcern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> delimitation ofits frontiers or boundaries.O<strong>the</strong>r titles <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity series <strong>in</strong>clude:Kormos & Hughes. 2000. Regulat<strong>in</strong>g Genetically Modified Organisms: Strik<strong>in</strong>g a Balance BetweenProgress and Safety (no. 1)Bakarr et al. 2001. Hunt<strong>in</strong>g and Bushmeat Utilization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> African Ra<strong>in</strong> Forest: Perspectives towarda Bluepr<strong>in</strong>t for Conservation Action (no. 2)Rice et al. 2001. Susta<strong>in</strong>able Forest Management: A Review of Conventional Wisdom (no. 3)Hannah & Lovejoy. 2003.Climate Change and Biodiversity: Synergistic Impacts (no. 4)Rodrigues et al. 2003.Global Gap Analysis: Towards a Representative Network of Protected Areas (no. 5)Oates et al. 2004. Africa’s Gulf of Gu<strong>in</strong>ea Forests: Biodiversity Patterns and Conservation Priorities (no.6)Please visit www.biodiversityscience.org for more <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>the</strong>se documents.

PrefaceThis study is <strong>in</strong>tended to review and revitalize <strong>the</strong> dialogue about conservation and development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>Area and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> two adjacent Biodiversity Hotspots, <strong>the</strong> Cerrado and <strong>the</strong> Tropical Andes. Although our discussiontouches on a variety of factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> possible paths for conservation and development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> trade-offs emerg<strong>in</strong>g from different scenarios, <strong>the</strong> central <strong>the</strong>me and motivat<strong>in</strong>g factor for <strong>the</strong> study is<strong>the</strong> Initiative for <strong>the</strong> Integration of <strong>the</strong> Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA). IIRSA is rapidly becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>organiz<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> push to improve physical l<strong>in</strong>ks among <strong>the</strong> South American countries via highways,hydrovias, energy projects and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>itiatives.The study attempts to evaluate IIRSA objectively by exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> likely changes it will br<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> region. It isnot <strong>in</strong>tended to be an anti-IIRSA diatribe. We recognize that IIRSA is, potentially, a visionary <strong>in</strong>itiative — one thatcan promote cultural exchange and stimulate economic growth. Regional <strong>in</strong>tegration can offset <strong>the</strong> harsher aspects ofglobalization and provide an alternative to <strong>the</strong> boom and bust cycles caused by an over-reliance on <strong>the</strong> export of commodities.IIRSA can become a solid step <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> direction of economic growth and poverty reduction and an essential<strong>in</strong>gredient for <strong>the</strong> future well-be<strong>in</strong>g of South America.Our hope is that this document will stimulate IIRSA to become an even more important and relevant <strong>in</strong>itiative,one that <strong>in</strong>corporates <strong>the</strong> vision of an ecologically and culturally <strong>in</strong>tact <strong>Amazon</strong>. Recent experiences <strong>in</strong> participatorydemocracy have shown that <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong>vestments can be modified to respond to <strong>the</strong> environmental concernsand social priorities of civil society. These forums have made important contributions to biodiversity conservationand provided economic opportunity for local communities. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> natural resources of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> are <strong>the</strong> foundationof <strong>the</strong> regional economy, all sectors of society should have <strong>in</strong>put on <strong>the</strong>ir use and management.We believe that our study provides a novel perspective on development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, question<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>abilityof <strong>the</strong> current forest management model, as well as <strong>the</strong> long-held assumption that large-scale agriculture is<strong>in</strong>herently nonviable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wet tropics. A special effort was made to describe <strong>the</strong> risk posed by global climate changeand its potential impact on forest function. If <strong>the</strong>re is a term that describes this analysis, it is <strong>the</strong> identification ofl<strong>in</strong>kages — between climate change and wildfire, deforestation and precipitation, forest fragmentation and speciesext<strong>in</strong>ction, ore m<strong>in</strong>es and hydroelectric power, to name a few.These issues are part of <strong>the</strong> larger question of “What constitutes susta<strong>in</strong>able development?” The current paradigmhas taken us halfway to our goal but has not (yet) succeeded <strong>in</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> essentially exploitive nature of naturalresource-based development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>. In most cases, it manages only to mitigate <strong>the</strong> most egregious negativeimpacts. The <strong>Amazon</strong> needs a new development paradigm that will promote economic growth and reduce poverty,while simultaneously promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conservation of natural resources and <strong>the</strong> long-term economic health of <strong>the</strong> region.How <strong>the</strong>n can we improve IIRSA or, more importantly, how can we make “development” work better <strong>in</strong> itsenvironmental, social and economic dimensions? This study provides <strong>the</strong> first regional-scale analysis (albeit prelim<strong>in</strong>ary)of <strong>the</strong> costs and benefits associated with <strong>the</strong> proposed <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong>vestments. There must be a serious effortto document <strong>the</strong> projected replacement cost <strong>in</strong> carbon emissions from deforestation; prelim<strong>in</strong>ary estimates are <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> tens of billions of dollars. Might not <strong>the</strong>se resources be used to subsidize productions systems that do not entailclear<strong>in</strong>g forest? At <strong>the</strong> very least, <strong>the</strong> costs and benefits from IIRSA must be reevaluated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of one <strong>the</strong>most important issues of our time: <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>Amazon</strong>ian development <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r mitigat<strong>in</strong>g or exaggerat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> impactof global warm<strong>in</strong>g. We need to understand how deforestation and climate change will impact precipitation patterns<strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent, because even a small reduction could reduce agricultural yields with enormouseconomic consequences.

South America conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> largest expanses of prist<strong>in</strong>e tropical forests rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g globally. This feature must berecognized as <strong>the</strong> foundation for development and <strong>the</strong> region’s pr<strong>in</strong>cipal comparative advantage. South America has anenormous economic <strong>in</strong>centive to conserve <strong>the</strong> ecosystem services provided by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, along with achiev<strong>in</strong>g real andeffective regional <strong>in</strong>tegration. These are not mutually exclusive goals. We are fully aware that this will require <strong>the</strong> participationof all sectors of society, but most importantly <strong>the</strong> communities that reside <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> and <strong>the</strong> enterprises thattransform <strong>the</strong> wealth of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>in</strong>to marketable goods and services. Local and national governments must lead thiseffort as part of <strong>the</strong>ir obligation to regulate <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions among different sectors of society. Conservation Internationalpresents this publication to <strong>the</strong>se audiences <strong>in</strong> order to jo<strong>in</strong> with <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong> a common effort to save <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>.Gustavo FonsecaTeam Leader, Natural ResourcesThe Global Environment Facility

Table of ContentsPreface............................................................................................................................................ 4Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 8Chapter 1. Introduction............................................................................................................... 11IIRSA Structure and Governance............................................................................................ 12The Future of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>: Three Scenarios............................................................................ 15Chapter 2. The Drivers of Change............................................................................................... 21Advance of <strong>the</strong> Agricultural Frontier....................................................................................... 22Forestry and Logg<strong>in</strong>g.............................................................................................................. 25Global and Regional Climate Change..................................................................................... 26Wildfire.................................................................................................................................. 29Hydrocarbon Exploration and Production.............................................................................. 29M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g................................................................................................................................... 33Hydroelectric Power and Energy Grids................................................................................... 35Biofuels.................................................................................................................................. 38Global Markets and Geopolitics............................................................................................. 39Chapter 3. Biodiversity................................................................................................................ 43Montane Forest...................................................................................................................... 44Lowland Tropical Ra<strong>in</strong>forest................................................................................................... 46Grasslands, Cerrados, and Dry Forests.................................................................................... 47Aquatic Ecosystems................................................................................................................ 50Chapter 4. Ecosystem Services..................................................................................................... 53The Value of Biodiversity........................................................................................................ 54Carbon Stocks and Carbon Credits......................................................................................... 57Water and Regional Climate................................................................................................... 60Chapter 5. Social Landscapes...................................................................................................... 63Migration, Land Tenure, and Economic Opportunity............................................................ 64Indigenous Groups and Extractive Reserves............................................................................ 66Migration and Human Health................................................................................................ 67The Manaus Free Trade Zone.................................................................................................. 68Chapter 6. Environmental and Social Evaluation and Mitigation............................................. 69Strategic Environmental Assessment....................................................................................... 70Susta<strong>in</strong>able Development Plans.............................................................................................. 71

Chapter 7. Avoid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> End of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>............................................................................... 73Rais<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Money: Monetiz<strong>in</strong>g Ecosystem Services................................................................ 75A Fair Exchange: Ecosystem Services for Social Services.......................................................... 75Quid Pro Quo........................................................................................................................ 76Subsidiz<strong>in</strong>g Alternative Production Systems............................................................................ 76Harness<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Power of Local Government........................................................................... 78Design<strong>in</strong>g Conservation Landscapes....................................................................................... 78Conclusions............................................................................................................................ 79References..................................................................................................................................... 80Appendix...................................................................................................................................... 90

Executive SummaryThe Initiative for <strong>the</strong> Integration of <strong>the</strong> Regional Infrastructureof South America (IIRSA) is a visionary program thatwill transform <strong>the</strong> countries of South American <strong>in</strong>to acommunity of nations. Unlike past diplomatic efforts andcustoms unions, IIRSA is an em<strong>in</strong>ently practical <strong>in</strong>itiativethat proposes to physically <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent ― longan historical goal of South America’s democracies. However,many of IIRSA’s planned <strong>in</strong>vestments will take place onparts of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent with ecosystems and cultures that areextremely vulnerable to change. This <strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>the</strong> world’slargest <strong>in</strong>tact tropical forest, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong> Area,which is situated between <strong>the</strong> Tropical Andes and <strong>the</strong>Cerrado Biodiversity Hotspots, two geographic regionscharacterized by an extraord<strong>in</strong>arily large number of speciesfound nowhere else on <strong>the</strong> planet. In addition, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>is home to numerous <strong>in</strong>digenous communities that arestruggl<strong>in</strong>g to adapt to a globalized world. Unfortunately,IIRSA has been designed without adequate considerationof its potential environmental and social impacts and thusrepresents a latent threat to <strong>the</strong>se ecosystems and cultures. Avisionary <strong>in</strong>itiative such as IIRSA should be visionary <strong>in</strong> allof its dimensions, and should <strong>in</strong>corporate measures to ensurethat <strong>the</strong> region’s renewable natural resources are conservedand its traditional communities streng<strong>the</strong>ned. Failure toforesee <strong>the</strong> full impact of IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments, particularly<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of climate change and global markets, willbr<strong>in</strong>g about a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of forces that could lead to aperfect storm of environmental destruction. At stake is<strong>the</strong> greatest tropical wilderness area on <strong>the</strong> planet, whichprovides multiple strategic benefits for local and regionalcommunities, as well as <strong>the</strong> entire world.The Need for IIRSA and a Concurrent ConservationStrategyIIRSA is motivated by <strong>the</strong> very real need to stimulateeconomic growth and reduce poverty among its membernations. As such, it contemplates a series of well-def<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> three strategic sectors: transportation, energy,and telecommunications. Some of its most important<strong>in</strong>vestments will upgrade roads that span <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>,Andes, and Cerrado and l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> Pacific and Atlantic coaststo create a modern cont<strong>in</strong>ental-scale highway system.Although <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>stitutions responsible for IIRSAhave relatively high standards for environmental andsocial evaluation, environmental assessments are l<strong>in</strong>kedto <strong>in</strong>dividual projects and do not consider <strong>the</strong> collectiveimpact of multiple <strong>in</strong>vestments. Nor do <strong>the</strong>y adequatelyaddress <strong>the</strong> long term drivers of change, such as agriculture,forestry, hydrocarbons, m<strong>in</strong>erals, and biofuels. For example,no environmental assessment has addressed <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k betweenimproved highways, <strong>in</strong>creased deforestation, and carbonemissions, nor how deforestation might impact local andcont<strong>in</strong>ental precipitation patterns.Conservation International (CI) is develop<strong>in</strong>g acomprehensive strategy to evaluate and monitor IIRSAand o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong>vestments based on <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsand recommendations of this document. This documentexam<strong>in</strong>es how development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region <strong>in</strong>volves local andregional actors, <strong>the</strong> importance of global commodity markets,and how climate change might impact <strong>the</strong>se phenomena<strong>in</strong>dividually and collectively. For example, agriculture is<strong>the</strong> largest driver of land-use change <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region and willexpand even faster and fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> response to global markets,as IIRSA highways make previously remote land accessibleand as new agricultural technologies make productionmore profitable. Modern transportation systems will lead tomore <strong>in</strong>tensive logg<strong>in</strong>g over wider areas, particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>previously remote western <strong>Amazon</strong> as it is l<strong>in</strong>ked to Asianmarkets via Pacific Coast ports.Improved river transport systems (hydrovias) willmake agricultural commodities, biofuels, and <strong>in</strong>dustrialm<strong>in</strong>erals from <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn and eastern <strong>Amazon</strong> morecompetitive <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational markets. Forest fragmentationand degradation caused by clear<strong>in</strong>g and logg<strong>in</strong>g will br<strong>in</strong>gabout an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> wildfires, which may also be exacerbatedby regional manifestations of global warm<strong>in</strong>g. Accelerateddeforestation will create a dangerous feedback loop withglobal atmospheric and ocean systems, accelerat<strong>in</strong>g globalwarm<strong>in</strong>g and perhaps alter<strong>in</strong>g ra<strong>in</strong>fall patterns at <strong>the</strong> local,cont<strong>in</strong>ental and global scale. These are all risks that needto be evaluated <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tegrated analysis, and IIRSA must<strong>in</strong>corporate measures to avoid or mitigate <strong>the</strong> most dangerousof <strong>the</strong>se impacts.IIRSA and similar <strong>in</strong>vestments will profoundly affect <strong>the</strong>region’s unique and vulnerable biodiversity. All but one of <strong>the</strong>ten IIRSA corridors <strong>in</strong>tersect a Biodiversity Hotspot or HighBiodiversity <strong>Wilderness</strong> Area—highly vulnerable regionsthat conta<strong>in</strong> species found nowhere else <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. In<strong>the</strong> montane forests of <strong>the</strong> Andes where <strong>the</strong>re are extremelyhigh levels of local endemism, any and all <strong>in</strong>vestments run arisk of creat<strong>in</strong>g an ext<strong>in</strong>ction event. In lowland <strong>Amazon</strong>ianra<strong>in</strong> forests renowned for <strong>the</strong> regional uniqueness of <strong>the</strong>irbiodiversity, deforestation belts around highways will lead tofragmentation that will <strong>in</strong>terfere with <strong>the</strong> ability of speciesto shift <strong>the</strong>ir geographic ranges <strong>in</strong> response to climatechange. The natural grasslands of <strong>the</strong> Cerrado will cont<strong>in</strong>ueto feel <strong>the</strong> brunt of agricultural development, with current

ates of habitat conversion <strong>the</strong>re lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> completedisappearance of natural habitats by 2030. An <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>effluents from chang<strong>in</strong>g terrestrial landscapes will degradeaquatic ecosystems, while rivers will be fragmented byhydroelectric power plants and waterways, compromis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>ability of fish populations.Conservation strategies and mitigation programs for thisdevelopment must be based on a thorough understand<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>the</strong> regional nature of <strong>Amazon</strong>ian biodiversity and mustgo beyond direct, immediate impacts of <strong>in</strong>dividual projectsto account for long-term and cumulative impacts. At risk isnot only <strong>the</strong> region’s rare abundance of biodiversity but <strong>the</strong>economic and social susta<strong>in</strong>ability of <strong>the</strong> development thatIIRSA is <strong>in</strong>tended to stimulate.Valu<strong>in</strong>g Conservation as Part of a Susta<strong>in</strong>ableDevelopment StrategyThe <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong> Area and <strong>the</strong> Andes andCerrado Hotspots provide ecosystem services to <strong>the</strong> worldvia <strong>the</strong>ir biodiversity, carbon stocks, water resources,and climate regulation. Locally, <strong>the</strong> region’s biologicalresources provide subsistence and <strong>in</strong>come to <strong>in</strong>habitants<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of fish, wildlife, fruit, and fiber, while natural,<strong>in</strong>tact ecosystems contribute enormous value to <strong>the</strong> world’seconomy. Unfortunately, current production systems tendto be exploitive, emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g short-term economic returnsthat are generally cyclical <strong>in</strong> nature, as well as economicallyand ecologically unsusta<strong>in</strong>able. Worse still, economiststend to discount ecosystems goods and services, as <strong>the</strong>y are<strong>in</strong>tangible and cannot be monetized <strong>in</strong> a traditional market.There is currently no mechanism or market that translates<strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>’s ecosystem services <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial resourcesnecessary to pay for its conservation or to subsidize <strong>the</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>able management of its renewable natural resources.The flora and fauna of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> has obvious <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sicvalue, although <strong>the</strong>re are limits on <strong>the</strong> ability of biodiversityto directly generate revenue. None<strong>the</strong>less, it plays anirreplaceable role <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g local economies and providespotential for economic growth through commercial venturessuch as aquaculture and ecotourism. The largest— andas yet unexploited — economic asset <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> is itscarbon stocks, which we estimate to be worth $2.8 trillionif monetized <strong>in</strong> today’s markets. Beyond that academiccalculation, <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> potential to generate revenueus<strong>in</strong>g more realistic models discussed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.N.Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).For example, if <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>ian countries agreed to reduce<strong>the</strong>ir deforestation rates by 5 percent each year for 30 years,this would potentially qualify as a reduction <strong>in</strong> greenhousegas emissions and generate about $6.5 billion annually over<strong>the</strong> life of <strong>the</strong> agreement. Distributed equally among <strong>the</strong>approximately 1,000 <strong>Amazon</strong>ian municipalities, this amountwould constitute about $6.5 million per community per yearthat could be used to support health and education, <strong>the</strong> toptwo priorities <strong>in</strong> most communities.IIRSA and Social Susta<strong>in</strong>abilityNo one can deny <strong>the</strong> urgent and palpable need toprovide <strong>Amazon</strong>ian residents with a dignified standardof liv<strong>in</strong>g. The impend<strong>in</strong>g changes that will emerge fromIIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with global marketswill def<strong>in</strong>itely have a large impact on current <strong>in</strong>habitantsof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, particularly traditional communities and<strong>in</strong>digenous groups that depend on natural ecosystemsfor <strong>the</strong>ir sustenance. On <strong>the</strong> positive side, IIRSA projectswill greatly reduce <strong>the</strong> isolation of rural communities andpromote economic growth and new bus<strong>in</strong>ess opportunities.History shows, however, that <strong>the</strong>se benefits will not be evenlydistributed and, <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stance, may fur<strong>the</strong>r marg<strong>in</strong>alize<strong>the</strong> rural poor if proper precautions are not taken.For example, highway corridors will stimulate <strong>the</strong>migration of hundreds of thousands, or even millions, ofpeople <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> region; new migrants will vie for resourceswith traditional communities, most of whose residents are illpreparedto compete with <strong>the</strong> more sophisticated immigrants.The creation of secure land registries and <strong>the</strong> recognition oftraditional use rights will be vital to ensur<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> currentresidents and <strong>in</strong>digenous communities are not shortchanged<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eventual—and <strong>in</strong>evitable— reconfiguration of<strong>Amazon</strong>ian society.Rapid cultural change also will br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>cidenceof alcoholism, suicide, prostitution, and HIV <strong>in</strong>fection.Local residents will need new skills to compete <strong>in</strong> moderneconomies and function well <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> new societies. Inaddition, health concerns need to be addressed: widespreadforest fire will <strong>in</strong>crease risk of lung diseases related tosmoke <strong>in</strong>halation, and forest pathogens will colonize newsettlements. None of <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>in</strong>significant challenges, and<strong>the</strong>y need to be addressed as an <strong>in</strong>tegrated part of susta<strong>in</strong>abledevelopment plans <strong>in</strong> order to ensure <strong>the</strong> development of avibrant society <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>.Can IIRSA be a Positive Force for Conserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>?Multilateral f<strong>in</strong>ancial agencies and <strong>the</strong>ir partnergovernments have often been harshly criticized for fail<strong>in</strong>g toidentify and mitigate <strong>the</strong> environmental and social impactsassociated with <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong>vestments. In response, <strong>the</strong>yhave committed to conduct<strong>in</strong>g comprehensive strategicenvironmental assessments (SEA) and ensur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> activeparticipation of local communities <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g bo<strong>the</strong>nvironmental and social impacts. However, this evaluationprocess must be enhanced <strong>in</strong> several ways if development is tobe truly susta<strong>in</strong>able while mitigat<strong>in</strong>g some of <strong>the</strong> impacts thisdocument identifies:

• Early assessment — SEAs should be conducted well <strong>in</strong>advance of <strong>the</strong> feasibility study so that recommendationscan be realistically <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> project design.• Increase scope of assessments — Assessment mustbeg<strong>in</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account secondary impacts and <strong>the</strong>cumulative impacts that accrue from multiple projects,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those f<strong>in</strong>anced by o<strong>the</strong>r agencies and privatesector <strong>in</strong>vestors.• Acknowledge economic motives — Susta<strong>in</strong>able developmentplans, which are <strong>in</strong>tended to avoid, mitigate orcompensate for <strong>the</strong> impacts identified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SEA, needto go beyond community based <strong>in</strong>itiatives—as importantas those may be—to address <strong>the</strong> economic motivationsof <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual land holder. The <strong>Amazon</strong> is notbe<strong>in</strong>g deforested by communities; it is be<strong>in</strong>g cleared anddegraded by <strong>the</strong> actions of <strong>in</strong>dividuals, family and corporate,and if <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> is to be saved from destruction,<strong>in</strong>dividuals must be motivated to change <strong>the</strong>ir behavior.The document concludes by provid<strong>in</strong>g a series ofrecommendations on how to improve IIRSA so that it canserve as a role model for development throughout <strong>the</strong> region,as well as <strong>the</strong> world. These policy recommendations areorganized <strong>in</strong>to two broad categories: Traditional approachesto environmental mitigation (i.e., <strong>the</strong> establishment ofnational systems of protected areas, complemented with<strong>in</strong>digenous reserves and <strong>the</strong> stewardship of private landfor conservation and susta<strong>in</strong>able forest management), andnontraditional approaches that focus on <strong>the</strong> potential forgenerat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>come from environmental services to subsidizeeconomic growth that avoids deforestation and rewardsconservation. These nontraditional approaches <strong>in</strong>clude suchrecommendations as:• Creat<strong>in</strong>g revenue by monetiz<strong>in</strong>g carbon credits — Sav<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> will require resources. Carbon marketsand voluntary mechanisms can raise <strong>the</strong>se resources and,at <strong>the</strong> same time, can be structured to respect <strong>the</strong> sovereignrights of <strong>in</strong>dividual nations to manage <strong>the</strong>ir ownnatural resources. This source of revenue can create a viablealternative to o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dustries that deforest naturalareas.• Ecosystem services should pay for social services — Asystem of economic payments for health and educationmust be created to compensate communities that protectecosystem services and limit deforestation.• Quid Pro Quo — Because conserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>will slow global warm<strong>in</strong>g, a worldwide security issue,<strong>the</strong> global community should respect <strong>the</strong> role of SouthAmerican countries <strong>in</strong> preserv<strong>in</strong>g world security (i.e.,grant Brazil membership <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.N. Security Counciland reform <strong>in</strong>ternational trade to recognize <strong>the</strong> concernsof South American nations).• People by air, cargo by water — Highways are only oneform of transportation. The <strong>Amazon</strong> river system is idealto transport bulk commodities (gra<strong>in</strong>s, m<strong>in</strong>erals, timberand biofuels), while subsidies for air transport couldmeet <strong>the</strong> transportation needs of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>’s far-flungcommunities.• Reform <strong>the</strong> land tenure system — The <strong>in</strong>security ofland tenure is a major driver of deforestation and conflict;long-overdue changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> normative frameworkcould reverse this paradigm so that forest conservation isrewarded ra<strong>the</strong>r than penalized.• Change <strong>the</strong> development paradigm — The <strong>Amazon</strong>needs production systems that are less subject to <strong>the</strong>fluctuations of <strong>in</strong>ternational commodity markets. Thiscan only be achieved by transform<strong>in</strong>g commodities <strong>in</strong>tomanufactured goods and services, along with <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> technology-based <strong>in</strong>dustries <strong>in</strong>dependent of naturalresources (i.e., Manaus Free Trade Zone).The countries of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, Andes and Guiana have allrecognized that <strong>the</strong> conservation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> is a strategicpriority. However, <strong>the</strong>y also are adamant that an even greaterstrategic priority is <strong>the</strong> need for economic growth to improve<strong>the</strong> social welfare of <strong>the</strong>ir populations. These comb<strong>in</strong>edpriorities lead to one logical policy option: <strong>the</strong> use of directand <strong>in</strong>direct subsidies to promote economic growth thatsimultaneously conserves crucial natural ecosystems. Thisis not aid, nor do <strong>the</strong> residents want charity or o<strong>the</strong>r handouts.They want decent jobs and opportunities for <strong>the</strong>irchildren. Future development must provide <strong>the</strong>m with both,or conservation efforts will fail. This new developmentparadigm must ensure <strong>the</strong> region’s <strong>in</strong>habitants a dignifiedlevel of prosperity while mak<strong>in</strong>g important contributionsto <strong>the</strong> economies of <strong>the</strong> nations that are custodians of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>. If <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> forest is a global asset worthpreserv<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>n it is only reasonable that <strong>the</strong> custodians bepaid for <strong>the</strong>ir efforts.10

Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity ScienceNo. 7, July 2007: pp. 11–19Chapter 1IntroductionDespite decades of encroachmentand degradation, <strong>the</strong> greater <strong>Amazon</strong>is still <strong>the</strong> world’s largest tropicalforest, conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g over 6 million squarekilometers of forest habitat (©HaroldoCastro/CI).The <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong> Area is <strong>the</strong> world’s largest <strong>in</strong>tact tropical forest. It is situated between <strong>the</strong> Tropical Andes Biodiversity Hotspotand <strong>the</strong> Cerrado Biodiversity Hotspot, two regions that are <strong>the</strong>mselves characterized by an extraord<strong>in</strong>arily large number of speciesfound nowhere else on <strong>the</strong> planet (Mittermeier et al. 1998, 2003). Although <strong>the</strong>se three regions are l<strong>in</strong>ked by climates, ecosystems, riverbas<strong>in</strong>s, and shared cultural experiences, <strong>the</strong> eight nations that share <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> have not succeeded <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir national economies.The Initiative for <strong>the</strong> Integration of <strong>the</strong> Regional Infrastructure of South American (IIRSA) was conceived to create a cont<strong>in</strong>entaleconomy, forg<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>ks between all of <strong>the</strong> countries <strong>in</strong> South America. IIRSA is a visionary <strong>in</strong>itiative and aspires to a level of <strong>in</strong>tegrationthat has long been an historical goal of all of <strong>the</strong> found<strong>in</strong>g fa<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s democracies. Its ultimate goal is to form a SouthAmerican identity <strong>in</strong> which citizens see <strong>the</strong>mselves as part of a s<strong>in</strong>gle community with a common future. Although previous efforts to-11

Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity Science Number 7, July 2007ward <strong>in</strong>tegration have been undertaken through treaty <strong>in</strong>itiativessuch as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> and Andean cooperation pacts and <strong>the</strong> Mercosurcustoms union, movement toward a common identity hasbeen elusive due to political differences and asymmetries <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>size and <strong>in</strong>ternal structure of <strong>the</strong> economies of member nations.IIRSA is an em<strong>in</strong>ently practical <strong>in</strong>itiative meant to complementdiplomatic <strong>in</strong>itiatives; its goal is to undertake specific actionsto l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> regions of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent physically <strong>in</strong> ways that willfoster trade and social <strong>in</strong>terchange among nations (Figure 1.1).IISRA is not an end <strong>in</strong> itself, nor even ano<strong>the</strong>r treaty mechanism,but a series of well-def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>vestments (IIRSA 2007) that willconvert South America <strong>in</strong>to a community of nations.IIRSA is motivated by <strong>the</strong> very real need to promote economicgrowth and reduce poverty among its member nations.However, it also threatens to accelerate <strong>the</strong> environmental degradationthat is jeopardiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> natural ecosystems of SouthAmerica. While it is true that <strong>the</strong> vast <strong>Amazon</strong>ian <strong>Wilderness</strong>Area has acted as a barrier to cultural and economic <strong>in</strong>terchange,it is arguably <strong>the</strong> world’s most important biological asset, at least<strong>in</strong> terms of terrestrial biodiversity, hold<strong>in</strong>g a disproportionateamount of <strong>the</strong> biological resources of <strong>the</strong> planet. Many of IIRSA’sdevelopment projects will directly <strong>in</strong>tersect with areas that conta<strong>in</strong>unique and vulnerable species (Figure 1.2).IIRSA is be<strong>in</strong>g pursued with a deliberate speed that reflects<strong>the</strong> political commitment of its member states. However, <strong>the</strong>rush to <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>the</strong> economies of <strong>the</strong> region should not be madeat <strong>the</strong> expense of <strong>the</strong> natural resources that are <strong>the</strong> foundationof <strong>the</strong>se same national economies. IIRSA will unleash economicforces that will provoke human migration <strong>in</strong>to areas that areextremely important for <strong>the</strong> conservation of biodiversity, andit will do so at scales and rates of change that <strong>the</strong> designers ofIIRSA have not yet considered, despite more than three decadesof experience <strong>in</strong> evaluat<strong>in</strong>g environmental impacts. Like <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itialthrust of <strong>Amazon</strong>ian development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1960s, manyproposed IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments are heedless of <strong>the</strong> environmentalconsequences and <strong>in</strong>different to social impacts. A visionary projectsuch as IIRSA should be visionary <strong>in</strong> all its components; mostimportantly, it should <strong>in</strong>corporate measures that guarantee <strong>the</strong>conservation of <strong>the</strong> region’s natural resources and <strong>the</strong> social welfareof <strong>the</strong> region’s traditional populations. Failure to foresee <strong>the</strong>full impact of IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments will br<strong>in</strong>g forth a comb<strong>in</strong>ationof effects that will create a perfect storm of environmental destruction,<strong>the</strong>reby degrad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> greatest tropical wilderness areaon <strong>the</strong> planet.This document provides an overview of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, Andes,and Cerrado regions. It describes <strong>the</strong> processes of economic development<strong>in</strong> relationship to local, regional, and global phenomena.It also exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> nature of biodiversity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se three ecologicallycomplex regions <strong>in</strong> order to highlight <strong>the</strong> vulnerabilityof <strong>the</strong>ir ecosystems to <strong>the</strong> impacts associated with IIRSA projects.In addition, <strong>the</strong> document highlights conservation and development<strong>in</strong>itiatives that have been successful and that could be replicated.F<strong>in</strong>ally, a series of policy recommendations are providedthat would avoid <strong>the</strong> most deleterious environmental impacts ofIIRSA. These recommendations are formulated not <strong>in</strong> oppositionto IIRSA, but to provide alternatives that would consolidateIIRSA’s mission to promote economic growth and development.IIRSA Governance and StructureFigure 1.1. IIRSA is composed of ten hubs that <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>in</strong>vestments<strong>in</strong> modern paved highways, railroads, waterways, and grids.The upgraded road networks will span <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, while waterways(hydrovias <strong>in</strong> IIRSA term<strong>in</strong>ology) will open up vast areas of<strong>the</strong> western <strong>Amazon</strong> to commerce and development (map modifiedfrom IDB 2006).IIRSA <strong>in</strong>volves all <strong>the</strong> countries of South America and wascreated to promote growth and development by <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>physical <strong>in</strong>tegration of three strategic economic sectors: transportation,energy, and telecommunications. Although IIRSA is not afree trade agreement, it addresses regulatory issues that are barriersto <strong>the</strong> economic and social exchange among <strong>the</strong> nations. IIRSApromotes common <strong>in</strong>dustrial standards and communicationprotocols, while facilitat<strong>in</strong>g border cross<strong>in</strong>gs for rail, maritime,and airl<strong>in</strong>e transport. IIRSA also sponsors meet<strong>in</strong>gs and studiesto promote commerce, and it facilitates technological exchange,<strong>in</strong>tegration of markets, and standardization of regulations (IDB2006). However, IIRSA’s most important <strong>in</strong>vestments are focusedon improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> physical <strong>in</strong>frastructure of transportation. IIRSAprojects are organized with<strong>in</strong> one of ten <strong>in</strong>tegration hubs (ejes<strong>in</strong> Spanish and eixos <strong>in</strong> Portuguese), each with several corridorscomposed of highways, hydrovias, and railroads, as well as electricalgrids and pipel<strong>in</strong>es (Figure 1.1). IIRSA is not a fund<strong>in</strong>gagency; ra<strong>the</strong>r, it is a coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g mechanism among <strong>the</strong> governmentsand <strong>the</strong> multilateral <strong>in</strong>stitutions that are responsible for f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>gmost of <strong>the</strong> public works <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> South America.IIRSA is governed by an Executive Steer<strong>in</strong>g Committee (CDE)and a Technical Coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g Committee (CCT). The CDEThe term hydrovia is used by IIRSA to denote a river waterway used for transportation.12A <strong>Perfect</strong> <strong>Storm</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>Conservation International

KilleenIntroductionFigure 1.2. Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal IIRSA highway corridors and hydrovias are shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong><strong>Wilderness</strong> Area and <strong>the</strong> Cerrado and Andes Biodiversity Hotspots. Conservation International organizespriority action <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se regions.is charged with develop<strong>in</strong>g a unified vision, def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g strategicpriorities, and approv<strong>in</strong>g periodic action plans. It is composedof representatives from each of <strong>the</strong> twelve member states, usuallyfrom <strong>the</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>istries, but occasionally <strong>in</strong>dividualsfrom <strong>the</strong> foreign or f<strong>in</strong>ancial m<strong>in</strong>istries (Figure 1.3). The CCTcomprises representatives from three regional f<strong>in</strong>ancial agencies:<strong>the</strong> Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), <strong>the</strong> Andean DevelopmentCorporation (CAF), and <strong>the</strong> F<strong>in</strong>ancial Fund for <strong>the</strong>Development of <strong>the</strong> River Plate Bas<strong>in</strong> (FONPLATA). It providesf<strong>in</strong>ancial and technical support, coord<strong>in</strong>ates meet<strong>in</strong>gs, and is <strong>the</strong>repository for IIRSA’s <strong>in</strong>stitutional memory. The CCT’s pr<strong>in</strong>cipalfunctions are to identify eligible projects, <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>the</strong> private sector,and organize <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ances. F<strong>in</strong>ally, IIRSA-approved projectsfor each <strong>in</strong>tegration hub are managed by Executive TechnicalGroups (GTE). These groups approve projects, review environmentaland social studies, and manage IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments.Projects are selected based on <strong>the</strong> tw<strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipals of susta<strong>in</strong>abilityand feasibility, with <strong>in</strong>dividual projects be<strong>in</strong>g analyzed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>context of a portfolio of <strong>in</strong>vestments and reflect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> consensusof <strong>the</strong> GTE (IDB 2006). In practice, approved projects are thosethat national plann<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>istries favor and present to <strong>the</strong> IIRSAexecutive and technical committees (Dourojeanni 2006). Currently,IIRSA’s agenda conta<strong>in</strong>s 335 projects, with 31 priorityprojects total<strong>in</strong>g more than $6.4 billion to be implemented <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> first phase of IIRSA, spann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> years 2005 to 2010 (Table1; Figure 1.4).Brazil has a complementary <strong>in</strong>itiative, similar to IIRSA both<strong>in</strong> philosophy and geographic scale, <strong>in</strong> which federal, state, andmunicipal governments are constitutionally mandated to presenta multiyear <strong>in</strong>tegrated development plan (Pluri-Annual Plan,Institutional titles are provided <strong>in</strong> English, but <strong>the</strong>ir acronyms follow thoseused on <strong>the</strong> IIRSA portal and by speakers of Spanish and Portuguese.or PPA by its Portuguese acronym) to <strong>the</strong>ir respective legislativebodies. The current PPA for 2004 to 2007, known as <strong>the</strong> “PlanoBrasil de Todos,” has three major objectives: 1) social <strong>in</strong>clusionand <strong>the</strong> reduction of social <strong>in</strong>equity, 2) economic growth andjob creation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of susta<strong>in</strong>able development and <strong>the</strong>reduction of <strong>in</strong>equality among regions, and 3) streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gdemocracy through participatory mechanisms. Because PPA’s primarygoal is to foster economic growth, many of its <strong>in</strong>vestmentswill improve <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration of <strong>the</strong> national transportation andenergy networks with neighbor<strong>in</strong>g countries.Most IIRSA projects are f<strong>in</strong>anced by loans from <strong>the</strong> threef<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>stitutions of CCT; however, f<strong>in</strong>ancial packages often<strong>in</strong>clude funds from national budgets, sovereign bond tenders,bilateral donors, and private sources arranged by <strong>the</strong> constructioncompanies that are contracted to execute <strong>the</strong> project. PPAf<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g comes from different public sources; most comes fromlocal, state, and federal budgets, but an important portion is providedby <strong>the</strong> National Social and Economic Development Bank(BNDES), a public entity associated with <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Development,Industry and Foreign Trade. In addition, BNDES f<strong>in</strong>ancesBrazilian operat<strong>in</strong>g companies <strong>in</strong> neighbor<strong>in</strong>g countries viaa program known as BNDES-EXIM that exists to promote <strong>the</strong>export of Brazilian goods and services. As a result, some IIRSAcontracts are awarded to consortia led by Brazilian constructioncompanies that have access to credit provided by BNDES orby o<strong>the</strong>r export promotion programs managed by <strong>the</strong> Banco doBrasil (Banco do Brasil 2007).In 2005, BNDES approved a total of $2.5 billion <strong>in</strong> loans to Brazilian exports;of this total approximately $1.06 billion was for exports to Argent<strong>in</strong>a, Chile,Ecuador, Paraguay, and Venezuela.BNDES has also <strong>in</strong>creased its participation <strong>in</strong> CAF, recently <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g itsshares from 2.5 percent to 5 percent, but not enough to have <strong>the</strong> same vot<strong>in</strong>gprivileges as <strong>the</strong> Andean countries (<strong>the</strong> so-called A shares).Center for Applied Biodiversity Science13

Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity Science Number 7, July 2007Table 1. A summary of IIRSA projected <strong>in</strong>vestments.Integration Axis (Eje) Corridors Segments Individual ProjectsEstimated Investment 1Priority F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g($ millions)($ millions) 2<strong>Amazon</strong>ia 7 91 8,027 1,215Andes 11 92 8,400 117Peru – Bolivia – Brazil 3 21 12,000 1,067Interoceanic 5 54 7,210 921.5Guayana Shield 4 44 1,072 121Sou<strong>the</strong>rn 2 22 1,100 n.a.Capricorn 4 27 2,702 65Mercosur – Chile 5 70 13,197 2,895Hydrovia Paraná – Paraguay 1 3 1,000 1Andes del Sur n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.Total 42 424 54,708 6,4031Modified from IIRSA (2007) and BICECA (2007).2IDB (2006).Institutional Structure of IIRSAExecutive Steer<strong>in</strong>g Committee (CDE)(Plann<strong>in</strong>g M<strong>in</strong>istries)Executive TechnicalGroups(GTE)<strong>Amazon</strong> HubAndes HubCentral Interoceanic HubGuyana HubPeru-Brazil-Bolivia HubO<strong>the</strong>r HubsSectorial IntegrationPrivate SectorNationalCoord<strong>in</strong>atorsTechnical Coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>gCommittee (CCT)IDBCAFFONPLATACCT SecretariatFigure 1.3. IIRSA structure. The Executive Steer<strong>in</strong>g Committee of IIRSA <strong>in</strong>cludes representatives from eachSouth American government. Projects are adm<strong>in</strong>istered by three multilateral lend<strong>in</strong>g agencies: <strong>the</strong> Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), <strong>the</strong> Andean Development Corporation (CAF), and <strong>the</strong> F<strong>in</strong>ancial Fund for <strong>the</strong>Development of <strong>the</strong> Río Plata (FONPLATA).Figure 1.4. IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments are largely concentrated <strong>in</strong> highway <strong>in</strong>frastructure, but <strong>the</strong>y also <strong>in</strong>clude o<strong>the</strong>r strategic transportation systems,as well as energy grids and communication systems (IDB 2006).14A <strong>Perfect</strong> <strong>Storm</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>Conservation International

KilleenIntroductionFigure 1.5. In a Utilitarian Scenario, an <strong>in</strong>fusion of private capital would convert <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>in</strong>to an agro-<strong>in</strong>dustrialpowerhouse that provides <strong>the</strong> planet with food, fiber, and biofuels, while allow<strong>in</strong>g for susta<strong>in</strong>able economicgrowth and social equity. <strong>Amazon</strong>ian countries would develop technological solutions to overcome agriculturalchallenges such as soil <strong>in</strong>fertility and weed control (© Hermes Just<strong>in</strong>iano/Bolivianature.com).Because of <strong>the</strong> adverse impacts associated with similar <strong>in</strong>vestments<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past, IIRSA <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure areviewed by many observers as a threat to <strong>the</strong> natural ecosystems of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> and surround<strong>in</strong>g regions. Fortunately, most of <strong>the</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ancial organizations <strong>in</strong>volved with IIRSA have relatively highstandards for environmental and social evaluation and usuallycondition loans on <strong>the</strong> implementation of environmental andsocial action plans. None<strong>the</strong>less, because <strong>in</strong>frastructure projectsare be<strong>in</strong>g evaluated <strong>in</strong>dividually, <strong>the</strong>y fail to consider how <strong>the</strong>comb<strong>in</strong>ation of projects and external forces such as global markets,transfrontier migration, or climate change might act synergisticallyto cause unforeseen effects. The academic communityhas provided valuable <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> potential future impactsand ample justification that a comprehensive evaluation procedureshould be required for both IIRSA and PPA (Laurance et al.2001, 2004, Nepstad et al. 2001, da Silva et al. 2005, <strong>Fearnside</strong>2006b).The Future of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>: Three ScenariosVirtually all South American societies support <strong>the</strong> conservationof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> forest and — simultaneously — call for<strong>in</strong>creased development that will provide residents of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>Multilateral banks have been more progressive on environmental and socialissues than commercial banks. For example, IDB and CAF have developed andadopted environmental guidel<strong>in</strong>es and Strategic Environmental Assessments,although <strong>the</strong>se have yet to be fully implemented. In contrast, FONPLATArequires only that projects meet <strong>the</strong> environmental norms of its member countries,and BNDES recently received poor rat<strong>in</strong>gs by an <strong>in</strong>dependent evaluationthat focused on commercial banks (WWF/BankTrack 2006).At <strong>the</strong> time of press, Strategic Environmental Assessments have been contractedor are underway for <strong>the</strong> corridor Puerto Suarez–Santa Cruz (IDB Project No.TC-9904003-BO0), <strong>the</strong> Corridor del Norte <strong>in</strong> Bolivia (IDB project BO-0200),and <strong>the</strong> InterOceanic Corridor <strong>in</strong> Madre de Dios, Peru (INRENA-CAF Project).Only one region-wide study was commissioned before 2006, which consisted ofan $81,000 consultancy contracted by IDB with funds provided by <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands;<strong>the</strong> contract was made to a private consult<strong>in</strong>g group, Golder Associates,of Boulder, Colorado.a dignified life free of poverty. There are enormous differencesamong people as to what this vision actually entails, particularlyregard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> preservation of wilderness areas, forest management,agricultural production, and land tenure. Most conservationistsview IIRSA as a traditional type of development that willlead to widespread deforestation; at <strong>the</strong> same time, many economistsand bus<strong>in</strong>ess people view <strong>the</strong> goals of <strong>the</strong> conservationmovement as an impediment to economic growth. Regardless of<strong>the</strong>se contrast<strong>in</strong>g viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts, it will be <strong>the</strong> economic markets and<strong>the</strong> decisions of democratic societies that will ultimately decide<strong>the</strong> fate of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>. It is impossible to predict this future, butit is possible, based on historical events and scientific research,to envision various scenarios that would likely follow differentpolicy implementations. This section provides three scenarios ofwhat <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> might look like after a century of human-<strong>in</strong>ducedchange. Two are decidedly optimistic <strong>in</strong> outlook, but diametricallyopposed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir philosophical underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs, whereas<strong>the</strong> third scenario is a more realistic view of what is most likely tooccur without a radical change <strong>in</strong> current public policies.The <strong>Amazon</strong> as Bread Basket (<strong>the</strong> Utilitarian Scenario)In this scenario, climate change and land use change <strong>in</strong>teract tocreate an <strong>Amazon</strong> that becomes progressively drier and warmer,and where <strong>the</strong> natural forest ecosystems are largely replaced bytree plantations and mechanized agriculture (Figure 1.5). Thisscenario is largely based on two assumptions: 1) <strong>the</strong> climate <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> will become drier and warmer, as predicted by climate-changemodels, lead<strong>in</strong>g to a collapse of <strong>the</strong> humid forestecosystem; and 2) <strong>the</strong>re will be massive deforestation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>as a result of decisions made by national governments and localpeople. The rema<strong>in</strong>der of <strong>the</strong> assumptions underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g thisscenario, specifically regard<strong>in</strong>g agricultural systems and economicgrowth, reflect modern society’s resilience and technological capacityto adapt to change.Center for Applied Biodiversity Science15

Advances <strong>in</strong> Applied Biodiversity Science Number 7, July 2007Global warm<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong> primary driver of change. Increas<strong>in</strong>gtemperatures and dryness cause ra<strong>in</strong>forest soils to respire at ratesgreater than trees photosyn<strong>the</strong>size; this shifts <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> ecosystem<strong>in</strong>to a net source of carbon, fur<strong>the</strong>r exacerbat<strong>in</strong>g globalwarm<strong>in</strong>g. The tree species of <strong>the</strong> humid forest ecosystem cannotadapt to <strong>the</strong> new climate conditions and are eventually elim<strong>in</strong>atedfrom <strong>the</strong> forest due to <strong>in</strong>creased adult mortality and lowerlevels of reproductive success. IIRSA’s transcont<strong>in</strong>ental highways<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> density of secondary roads, so that with<strong>in</strong> a centuryeventually 70 percent of <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al forest cover is replaced withpastures, crops, or tree plantations. Once it becomes clear thattree species are under physiological threat from climate change,governments adopt policies to monetize timber reserves ra<strong>the</strong>rthan lose <strong>the</strong>m to natural processes of mortality and decay. Theforest ecosystem essentially collapses and is replaced by an agriculturalproduction system that consolidates Brazil as <strong>the</strong> mostimportant producer of agricultural foodstuffs and biofuels <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>world.Technology will allow <strong>the</strong> agricultural sector to adapt toclimatic change. Archeological reconstructions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central<strong>Amazon</strong> have revealed how Amer<strong>in</strong>dian civilizations improvedsoil resources and susta<strong>in</strong>ed fertility over <strong>the</strong> long term us<strong>in</strong>gceramics and charcoal to ameliorate soil acidity and <strong>in</strong>crease organicmatter Modern agricultural science has rediscovered <strong>the</strong>semanagement techniques and adopted <strong>the</strong>m for both perennialand annual production systems. Agriculture will become morediversified with annual crops predom<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> best soils,whereas cattle ranches and tree farms will prevail on roll<strong>in</strong>g topography.The production of biofuels will become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>glyimportant, with plantations of sugar cane produc<strong>in</strong>g alcohol andoil palm for biodiesel fuel. Research will improve pest control us<strong>in</strong>ggenetically modified organisms <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with an ever<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>garsenal of pesticides. Farms that specialize <strong>in</strong> highlyproductive perennial species will make <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>the</strong> most productiveagricultural region <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world on a per hectare annualbasis.Although precipitation will decl<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>will still be <strong>the</strong> world’s largest freshwater hydrological system,conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> world’s largest underground aquifer. Irrigationtechnology, powered from <strong>the</strong> western <strong>Amazon</strong>’s abundant naturalgas reserves and from locally produced biofuels, will mitigateseasonal fluctuations <strong>in</strong> precipitation. Dams and reservoirs willcontribute surface water to <strong>the</strong> irrigation system and provide affordablehydroelectric power for urban centers with an <strong>in</strong>dustrialeconomy focused on metallurgy, forest products, and food process<strong>in</strong>g.There will be cont<strong>in</strong>ued migration from rural to urbanareas, particularly <strong>in</strong> cities such as Iquitos, Peru, and Leticia,Colombia, which will follow <strong>the</strong> example of Manaus, Brazil, todevelop economies based on manufactur<strong>in</strong>g, f<strong>in</strong>ancial services,and technological <strong>in</strong>novation.These radical changes to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> will cause envi-The dimensions of <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn part of this aquifer were recently mapped <strong>in</strong>Santa Cruz, Bolivia (Cochrane et al. 2007). The geology of <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>, known as<strong>the</strong> Andean foredeep, is composed of loosely consolidated sediments that havebeen charged with water over several million years. Because this is a nonconf<strong>in</strong>edaquifer, it is recharged cont<strong>in</strong>uously from surface sources and has <strong>the</strong>potential for a truly susta<strong>in</strong>able irrigation system.ronmental impacts at <strong>the</strong> global, regional, and local levels. At <strong>the</strong>global level, <strong>the</strong> collapse of <strong>the</strong> forest ecosystem will exacerbateglobal warm<strong>in</strong>g. Carbon reserves of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> will be released<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> atmosphere; <strong>the</strong> carbon emitted from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>gthis century will be equivalent to about 13 years of <strong>in</strong>dustrialemissions.Precipitation regimes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> and surround<strong>in</strong>g areaswill be affected by both global and regional manifestations ofclimate change. However, moderate levels of ra<strong>in</strong>fall over <strong>the</strong>central <strong>Amazon</strong> will be guaranteed by <strong>the</strong> trade w<strong>in</strong>ds that transportwater vapor from <strong>the</strong> Atlantic Ocean. Deforestation willnegatively impact <strong>the</strong> convective systems that recycle about 50percent of <strong>the</strong> precipitation that falls on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>; this willcause dry seasons to become longer and more severe. The lowleveljet stream system that modulates <strong>the</strong> seasonal monsoon andtransports water vapor from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> to <strong>the</strong> Río Plata bas<strong>in</strong>will <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensity but will transport less water due to <strong>the</strong>drier conditions that predom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> western <strong>Amazon</strong>. None<strong>the</strong>less,<strong>the</strong> agricultural productivity of <strong>the</strong> lower Río Plata bas<strong>in</strong>will not be severely affected because o<strong>the</strong>r wea<strong>the</strong>r systems will<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> precipitation that orig<strong>in</strong>ates over <strong>the</strong> South Atlantic.Biodiversity conservation will be managed by a reserve systemof protected areas that was established <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last decade of<strong>the</strong> twentieth century and will cont<strong>in</strong>ue <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> first two decadesof <strong>the</strong> twenty-first century. Like protected areas <strong>in</strong> North Americaand Europe, <strong>the</strong>se are island-like preserves conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a representativesample of <strong>the</strong> biodiversity that existed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> priorto <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrialization of agriculture. As predicted by conservationbiologists, this level of isolation will cause <strong>the</strong> widespreadext<strong>in</strong>ction of many endemic species and <strong>the</strong> homogenization ofmany of <strong>the</strong> biota with<strong>in</strong> protected areas. Ecosystem fragmentationwill limit <strong>the</strong> ability of many species to migrate <strong>in</strong> response toglobal warm<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>refore caus<strong>in</strong>g even more ext<strong>in</strong>ctions.The economic growth from agriculture, cattle ranch<strong>in</strong>g,and plantation forestry will create a favorable bus<strong>in</strong>ess environmentand <strong>in</strong>crease employment opportunities. Prosperity will<strong>in</strong>crease tax revenues and allow greater <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> educationand health services. The skilled professionals needed to manage<strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial, <strong>in</strong>dustrial, and commercial <strong>in</strong>stitutions will migrate<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> from urban centers of South America (e.g.,São Paolo, Bogotá, and Lima). Indigenous peoples will adapt tochange by rely<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>ternal social organizations as a bulwarkaga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> homogenization of <strong>the</strong>ir cultures and to protect<strong>the</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>terests of <strong>the</strong>ir communities. However, <strong>the</strong> mostimportant element <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir success is <strong>the</strong> advantage of be<strong>in</strong>ggranted clear title to large expanses of land. As <strong>the</strong> group with <strong>the</strong>largest land area <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y will use this asset to engage<strong>in</strong> economic growth through agricultural production and plantationforestry.In this Utilitarian Scenario, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>ian nations have successfully<strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>the</strong>ir economies, and Brazil has evolved <strong>in</strong>toone of <strong>the</strong> most prosperous and dynamic nations on <strong>the</strong> planet.Its large population and stable economy act as <strong>the</strong> economic motorfor <strong>the</strong> region and provide much of <strong>the</strong> technological <strong>in</strong>novationbeh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>able, productive systems that now characterize<strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong>. The Andean countries have close commercialties with Brazil, and <strong>the</strong> economic growth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> is l<strong>in</strong>ked16A <strong>Perfect</strong> <strong>Storm</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amazon</strong> <strong>Wilderness</strong>Conservation International