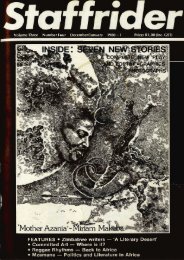

Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

five' to George Goch passed Mzimhlopewhile I was there. This train brought thefree morning stuntman show. The daredevilsran along the roof of the train, afew centimetres from the naked cablecarrying thousands of electric volts, andducked under every pylon. One mistimedstep, a slip — and reflex action wouldsend his hand clasping for support. Nocomment from any of us at the station.The train shows have been going onsince time immemorial and have losttheir magic.My train to Faraday arrived, burstingalong the seams with its load. Thespaces between the adjacent coacheswere filled with people. So the onlyway I could get on the train was bywedging myself among those hanging onperilously by hooking their fingers intothe narrow tunnels along the tops of thecoaches, their feet on the door ledges. Aslight wandering of the mind, a suddenswaying of the train as it switched lines,bringing the weight of the others on topof us, a lost grip and another labour unitwould be abruptly terminated. We hungon for dear life until Faraday.In Pieters' office. Four automatictelephones, two scarlet and two orangecoloured, two fancy ashtrays, a gildedball-pen stand complete with gilded penand chain, two flat plastic ashtrays andbaskets, the one on the left marked INand the other one OUT, all displayed onthe poor bland face of a large highlypolished desk. Under my feet a thickcarpet that made me feel like a piece ofdirt. On the soft opal green wall on myleft a big framed 'Desiderata' and aboveme a ceiling of heavenly splendour.Behind the desk, wearing a short creamwhitesafari suit, leaning back in a regalflexible armchair, his hairy legs (the paleskin of which curiously made me thinkof a frog's ventral side) balanced on theedge of the desk in the manner of asheriff in an old-fashioned western, myblue-eyed, slightly bald, jackal-facedoverlord.'You've got your pass?''Yes, mister Pieters.' That one didnot want to be called baas.'Let me see it. I hope it's the rightone. You got a permit to work inJohannesburg?''I was born here, mister Pieters.' Myhands were respectfully behind me.'It doesn't follow.' He removed hislegs from the edge of the table andopened a drawer. Out of it he took asmall bundle of typed papers. Hesigned one of them and handed it to me.'Go to the pass office. Don't spend twodays there. Otherwise you come back andI've taken somebody else in your place.'He squinted his eyes at me andwagged his tongue, trying to amuse methe way he would try to make a babysmile. That really amused me, histrying to amuse me the way he would ababy. I thought he had a baby's mind.'Esibayeni'. Two storey red-brickbuilding occupying a whole block.Address: 80 Albert street, or simply'Pass Office'. Across the street, halfthe block (the remaining half a parkingspace and 'home' of the homelessmethylated spirit drinkers of the city)taken up by another red-brick structure.Not offices this time, but 'Esibayeni'(at the kraal) itself. No questionwhy it has been called that. Thewhole black population of Johannesburgabove pass age knows that place.Like I said, it was full on a Monday,full of wretched men with defeatedeyes, sitting along the gutters on bothsides of Albert street, the whole passoffice block, others grouped where thesun's rays leaked through the skyscrapersand the rest milling about.When a car driven by a white manwent up the street pandemonium brokeloose as men, I mean dirty slovenlymen, trotted behind it and fought togive their passes first. If the whiteperson had not come for that purposethey cursed him until he went outof sight. Occasionally a truck or vanwould come to pick up labourersfor a piece job. The clerk would shoutout the number of men that werewanted for such and such a job, sayforty, and double the number wouldbe all over the truck before you couldsay 'stop'. None of them would want tomiss the cut, which caused quite someproblems for the employer. A shrewdbusinessman would take all and simplydivide the money he had laid out amongthe whole group, as it was left to him todecide how much to pay for a piece job.Everybody was satisfied in the end —the temporary employer having hiswork done in half the time he had bargainedfor, and each of the labourerswith enough for a ticket back to thepass-office the following day, andmaybe ten cents worth of dishwaterand bread from the oily restaurants inthe neighbourhood, for three days.Those who were smart and familiar withthe ways of the pass-office handedtheir passes in with twenty and/orfifty-cent pieces between the pages.This gave them first preference of thebetter jobs.The queue to 'Esibayeni' was movingslowly. It snaked about thirty metresaround the corner of Polly street. It hadtaken me more than an hour to reachthe door. Inside the ten-feet high wallwas an asphalt rectangle, longitudinalbenches along the opposite wall in theshade of narrow tin ledges, filled withbored looking men, toilets on the lowerside of the rectangle, facing wide bustlingdoors. It would take me another threehours to reach the clerks. If I finishedthere just before lunch-time, it meantthat I would not be through with myregistration by four in the afternoonwhen the pass office closed. FortunatelyI had twenty cents and I knew that theblackjacks who worked there werenothing but starving leeches. One tookme up the queue to four people whostood before a snarling white boy. Thosewhose places ahead of me in the queuehad been usurped wasted their breathgrumbling.The man in front of me could notunderstand what was being bawledat him in Afrikaans. The clerk gave upexplaining, not prepared to use anyother language than his own. I felt thatat his age, about twenty, he should be atRAU learning to speak other languages.That way he wouldn't burst a vein tryingto explain everything in one tongue justbecause it was his. He was either boneheadedor downright lazy or else impatientto 'rule the Bantus'.He took a rubber stamp and bangedit furiously on one of the pages ofthe man's pass, and threw the book intothe man's face. 'Go to the other building,stupid!'The man said, 'Thanks,' and elbowedhis way to the door.'Next! Wat soek jy?' he asked in abellicose voice when my turn to besnarled at came. He had freckles all overhis face, and a weak jaw.I gave him the letter of employmentand explained in Afrikaans that Iwanted E and F cards. My talking in histongue eased some of the tensionout of him. He asked for my pass in aslightly calmer manner. I gave it tohim and he paged through. 'Good, youhave permission to work in Johannesburgright enough.' He took two cardsfrom a pile in front of him and laboriouslywrote my pass numbers on them.Again I thought that he should still beat school, learning to write properly. Hestamped the cards and told me to go toroom six in the other block. There wereabout twelve other clerks growling atpeople from behind a continuousU-shaped desk, and the space in front ofthe desk was overcrowded with peoplewho made it difficult to get to the door.Another blackjack barred the entranceto the building across the street.'Where do you think you're going?''Awu! What's wrong with you? I'mgoing to room six to be registered.You're wasting my time,' I answered inan equally unfriendly way. His eyeswere bloodshot, as big as a cow's and asstupid, his breath was fouled with( mai-mai\ and his attitude was a longway from helpful.He spat into his right hand, rubbedhis palms together and grabbed astick that was leaning against the wallnear him. 'Go in,' he challenged, indica-STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 5