You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

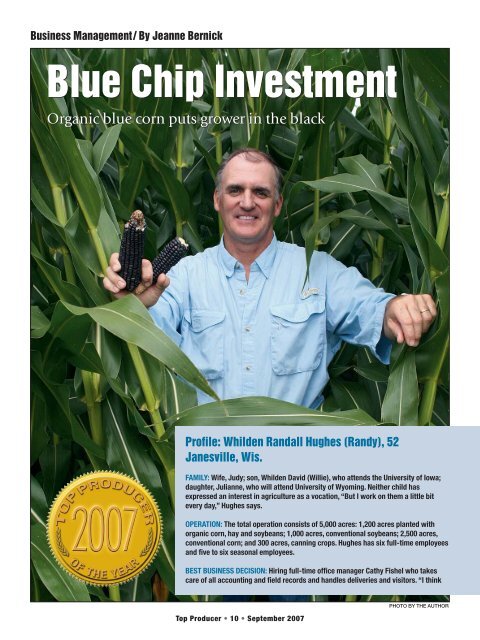

Business Management / By Jeanne BernickBlue Chip InvestmentOrganic blue corn puts grower in the blackProfile: Whilden Randall <strong>Hughes</strong> (<strong>Randy</strong>), 52Janesville, Wis.FAMILY: Wife, Judy; son, Whilden David (Willie), who attends the University of Iowa;daughter, Julianne, who will attend University of Wyoming. Neither child hasexpressed an interest in agriculture as a vocation, “But I work on them a little bitevery day,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says.OPERATION: The total operation consists of 5,000 acres: 1,200 acres planted withorganic corn, hay and soybeans; 1,000 acres, conventional soybeans; 2,500 acres,conventional corn; and 300 acres, canning crops. <strong>Hughes</strong> has six full-time employeesand five to six seasonal employees.BEST BUSINESS DECISION: Hiring full-time office manager Cathy Fishel who takescare of all accounting and field records and handles deliveries and visitors. “I thinkTop Producer • 10 • September 2007PHOTO BY THE AUTHOR

<strong>Randy</strong> <strong>Hughes</strong>’ blue chipinvestment has little todo with stocks andeverything to do withstalks. A decade ago, theJanesville, Wis., producer decided hehad to diversify his crop portfoliobeyond traditional No. 2 yellow corn.He placed his bets on raisingorganic blue corn—specifically anold, Native American variety withdark, purplish-blue, slender ears.Today you can buy his blue corn in theform of tortilla chips, namely BlueFarm Organically Grown Blue CornTortilla Chips, sold in stores across theMidwest. <strong>Hughes</strong> has increased hisbottom line by one-third in the lastdecade growing 1,200 acres of bluecorn and other organic crops.“Other than blueberries, therearen’t many blue foods around,” says<strong>Hughes</strong>, who cooked up the idea ofhis own branded blue corn chips witha retailer friend. “The fact that they areorganic gives them even more value.”He also grows white corn, clear anddark hilum soybeans, snap beans,beets, peas and sweet corn forcanning. But it’s the blue chipbusiness that has led to real profits.“When yellow corn was selling for$2, blue corn was about $7 perbushel,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says. “And I can growit on my marginal land, allowing aprofit off that ground that would notbe possible with commercial grain.”With organic blue corn there is alsoless hauling, less cash outlay forfertilizer, weed and insect control, anda continually growing natural market.Blue beginnings. <strong>Hughes</strong> wentblue after watching his father,Whilden <strong>Hughes</strong>, struggle throughthe debt crunch of the 1980s. The<strong>Hughes</strong> family had grown yellow cornon their land for more than acentury—<strong>Randy</strong> is the fifth <strong>Hughes</strong> toown and operate the farm, which wasgranted to his great, great grandfatherby President James Polk in 1848.“We’d hauled yellow corn to theelevator for years and Iwas tired of competingwith every farmer in theworld,” says <strong>Hughes</strong>, frombehind a massive desk ina former helicopterrepair building thatserves as his office andmachine shop.When local retailerDeLong Co. approached <strong>Hughes</strong> in1991 looking for ground to groworganic blue corn, he seized theopportunity. Having worked withthem previously on identity preservedproducts, <strong>Hughes</strong> saw an opportunityto become more competitive in theagricultural industry.“The first few crops were nervewracking,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says. It’s not aneasy journey from blue seed to blueear. The blue corn falls into a 120-daymaturity range, compared with thelongest variety of yellow corn hegrows at a 109-day maturity. Yet thecorn can’t be planted earlier becauseit’s organic and not protected by anyfungicidal coating, meaning the seedcan rot in the ground under poorweather conditions.the last time we missed an early pay discount was the last time I paid the billsmyself,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says.FAVORITE HOBBY: Restoring and driving vintage automobiles, including his cherry red1967 Chevelle convertible.COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT: In 1998, the <strong>Hughes</strong> family created a 10-acre corn mazein conjunction with the Wisconsin sesquicentennial, which brought 50,000 visitors tothe farm over three months. The maze gained worldwide attention with storiespublished in The Wall Street Journal and People magazine. Last year, <strong>Hughes</strong> broughtawareness of organic agriculture to his community by providing combine rides and aharvest lesson to 60 third-grade students. “The kids not only learned about organiccorn and its origination, they really enjoyed the snack of blue corn chips,” he says.BUSINESS STRENGTH: “My ability to be creative, innovative and think outside the box ismy strength,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says. “I also have a knack for putting a deal together.”Top Producer • 11 • September 2007It’s not an easyjourney fromblue seed toblue cornOnce it does germinate, the organiccrop can’t be sprayed with chemicalpesticides. Instead, <strong>Hughes</strong> relies ontwo rotary hoeings and as manycultivations as he can achieve.Several years into growing bluecorn, <strong>Hughes</strong> decided the seed qualityneeded to be improved. He spent timein Chile and Hawaii working withpioneering seed breeder Bob Tracey toplant, pollinate and choose the bestfew ears from hundredsof plants to create betterinbred lines of blue corn.The result is ears of nicecolor and size that yield80 bu./acre.Currently, <strong>Hughes</strong> istackling the issue oforganic blue corn’s openpollination and itstypical problems with emergence,standability and dry down. Anotherconcern is contamination from aseparate field of genetically modified(GMO) crop. <strong>Hughes</strong> has been able toprevent this by choosing fields for hisblue corn seed that have naturalbarriers, such as trees and roads.He is also working with HoegemeyerSeeds and Syngenta to create a non-GMO blue corn hybrid with a trait toonly accept its own pollen. Thismeans <strong>Hughes</strong> could plant his bluecorn in any field with less worryabout the surroundings, giving himmore options for planting sites. Hebelieves the technology is about sixyears off for blue corn.Chip, chip hooray. Once his bluecorn is harvest ready, <strong>Hughes</strong> picks thecorn, ears intact, and sends it to aprocessor for drying and shelling. It isthen bagged and shipped back to<strong>Hughes</strong>’ farm for warehousing andsent to the chip manufacturer asneeded to be made into corn chips.The final product is returned to<strong>Hughes</strong> in Blue Farm-branded bags.<strong>Hughes</strong> admits it has taken years tounderstand the food business (seeTips for Starting a Branded FoodBusiness, pg. 14). To begin, <strong>Hughes</strong>contacted McClearys Industries,which was already making its ownblue chip. He brought them a sampleof his blue corn and his own recipe forchips. The company liked his product,but required a truckload of cornbefore they would run a batch.▼

When he finally produced enoughcorn to fill a truck and deliver it to theprocessor, half expired before hecould get the chips into a retail store.“In the food business, you must bepatient and keep a high level ofquality in mind,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says. Aftermore trial runs and several processors,<strong>Hughes</strong> and a new processor found aproduction method that producedconsistent quality chips. His first retailsales were in a local Blains Farm andFleet store, which helped spread hisbrand to local consumers.“The chips took off after that,”<strong>Hughes</strong> says. “I think I had a lot offriends in Wisconsin buying my chipsin the early days.”Today, <strong>Randy</strong>’s wife Judy managesdirect chip distribution to storesthrough their company, A-Maize-ingCorn Products. Judy and the officemanager, Cathy Fishel, work withlarge distributors to get their productout to stores across the Midwest.For retailers within a 30-mile radiusof the farm, <strong>Randy</strong> or Judy deliver thechips personally. It gives them achance to check in with store ownersabout product quality and anycustomer concerns.“The chip business has been a reallesson in marketing and dealing withthe public,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says. He notesthat when he visits a store, he hadbetter be on time and have hispaperwork in order, and there hadbetter be no damaged cases.Tips for Starting a Branded Food Business<strong>Randy</strong> <strong>Hughes</strong> didn’t know thefirst thing about the retail foodbusiness when he started A-MaizeingCorn Products Inc., whichproduces and distributes his BlueFarm organic blue corn tortilla chips.Ten years later, <strong>Hughes</strong> offersthese tips for starting a brandedfood business:• Insist on quality at the processorlevel. “If your first product out ofthe chute is stale or inconsistent,the customer won’t return,”<strong>Hughes</strong> says.• Customer service matters. Visitretail stores personally to hearcomplaints and check in withstore managers. <strong>Hughes</strong> alsoresponds to retailer andcustomer phone calls promptly.• Seek advice from someoneestablished in a retail business.“Farmers are used to selling acrop in two phone calls, but inretail, it can take 100 calls,” hesays. <strong>Hughes</strong> often soughtadvice from a friend who owneda retail hardware store in town.PHOTO BY THE AUTHOR“As a farmer, I had always been abuyer of product,” he adds. “Now,people come to me with questions orconcerns or demands about product.”<strong>Hughes</strong>’ creativity has brought anew way of thinking to his bankpartner. “I like working with <strong>Randy</strong>because he so innovative andcreative,” says Jim Raymond, vicepresident of M&I Bank, who has been<strong>Hughes</strong>’ banker for 25 years.“For the most part, I prefer farmersto make the main thing on theiroperation the main thing for theirbusiness, which is typically productionagriculture,” Raymond says. “But<strong>Randy</strong> is unique. He can see a nichemarket and turn it into a successfulbusiness.“When <strong>Randy</strong> comes in with somebizarre idea, I’m apt to give him somelatitude because his track record is sogood,” Raymond says.Peace with the land. One landstrategy that frees up cash and allows<strong>Hughes</strong> to farm additional land isselling land and then renting it back.He recently sold 500 acres to one ofhis landlords who owned an adjacentpiece. <strong>Hughes</strong> rented itback long term and usedthe money from the saletoward more land.“I can make moneyrenting land and farmingit, and it’s been a way forme to grow withouthaving to own so muchland,” <strong>Hughes</strong> says.In high school, <strong>Hughes</strong>dreamed of becoming alarge enough farmer toproduce enough corn sohe could affect theChicago Board of Trade.Today, he dreams ofhow organic agriculturecan positively impactsmall farms and reapbenefits for humanhealth and environmentalpreservation. Despite itsrisks, <strong>Hughes</strong> believesorganic farming hasmade him a better farmerand a better person.“I like working withmother nature instead oftrying to beat her at herown game,” he says. “With identitypreservedgrains and especiallyorganics, we found a market that paysfor our efforts.”After that, he lets the chips fallwhere they may. ■To contact Jeanne Bernick, e-mailjbernick@farmjournal.com.FOR MORE INFORMATIONvisit www.ToProducer.comand click on Web Extra tolearn about risks and rewardsof organic production.Top Producer • 14 • September 2007