Planning education to care for the earth - IUCN Knowledge Network

Planning education to care for the earth - IUCN Knowledge Network

Planning education to care for the earth - IUCN Knowledge Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong><strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Joy Palmer, Wendy Goldstein, Anthony CurnowEdi<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>IUCN</strong> Commission on Education and Communication

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>

<strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation UnionFounded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r States,government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizationsin a unique world partnership: over 800 members in all, spread across some132 countries.As a Union, <strong>IUCN</strong> seeks <strong>to</strong> influence, encourage and assist societiesthroughout <strong>the</strong> world <strong>to</strong> conserve <strong>the</strong> integrity and diversity of nature and <strong>to</strong>ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologicallysustainable. A central secretariat coordinates <strong>the</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> Programme andserves <strong>the</strong> Union membership, representing <strong>the</strong>ir views on <strong>the</strong> world stageand providing <strong>the</strong>m with <strong>the</strong> strategies, services, scientific knowledge andtechnical support <strong>the</strong>y need <strong>to</strong> achieve <strong>the</strong>ir goals. Through its sixCommissions, <strong>IUCN</strong> draws <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r over 6000 expert volunteers in projectteams and action groups, focusing in particular on species and biodiversityconservation and <strong>the</strong> management of habitats and natural resources. TheUnion has helped many countries <strong>to</strong> prepare National ConservationStrategies, and demonstrates <strong>the</strong> application of its knowledge through <strong>the</strong>field projects it supervises. Operations are increasingly decentralized and arecarried <strong>for</strong>ward by an expanding network of regional and country offices,located principally in developing countries.The World Conservation Union builds on <strong>the</strong> strengths of its members,networks and partners <strong>to</strong> enhance <strong>the</strong>ir capacity and <strong>to</strong> support globalalliances <strong>to</strong> safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels.<strong>IUCN</strong> - Commission on Education andCommunication - CECThe Commission on Education and Communication is one of <strong>IUCN</strong>’s sixCommissions, a global network of voluntary, active and professional expertsin environmental communication and <strong>education</strong>, who work in NGO,government and international organisations, professional networks andacademic institutions. The daily work of CEC members is about how <strong>to</strong>encourage people <strong>to</strong> take responsibility in <strong>the</strong>ir personal and social behaviour<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment. CEC specialists are experts in learning processes, howbehaviour is changed and in communication management.The CEC network facilitates exchange and improves expertise in how <strong>to</strong>motivate and guide people’s participation, through <strong>education</strong> andcommunication, <strong>to</strong> conserve and sustainably use natural resources. The CECnetwork also advocates <strong>the</strong> value of <strong>education</strong> and communication.The CEC vision is that if we seek <strong>to</strong> conserve biodiversity, <strong>to</strong> use renewableresources sustainably and <strong>to</strong> develop sustainably, <strong>the</strong>n environmentalconsiderations have <strong>to</strong> become a vital fac<strong>to</strong>r in all our decision making. Tohave environmental concerns become <strong>the</strong> basis of all people’s thinking anddoing is <strong>the</strong> vision of CEC.

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong><strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Joy Palmer, Wendy Goldstein, Anthony Curnow, Edi<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>IUCN</strong> - Commission on Education and Communication<strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union 1995

Published by:<strong>IUCN</strong>, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UKCopyright:(1995) International Union <strong>for</strong> Conservation of Nature andNatural ResourcesReproduction of this publication <strong>for</strong> <strong>education</strong>al or o<strong>the</strong>rnon-commercial purposes is authorised without priorwritten permission from <strong>the</strong> copyright holder.Reproduction of this publication <strong>for</strong> resale or o<strong>the</strong>rcommercial purposes is prohibited without priorwritten permission of <strong>the</strong> copyright holder.Citation: Palmer, J., Goldstein, W. and Curnow, A. (Eds). 1995.<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>. <strong>IUCN</strong>, Gland,Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. x+169 pp.ISBN: 2-8317-0296-8Printed by:SADAG, Bellegarde-sur-Valserine, FranceCover : Repeating image adapted from Shaffer, Frederick W.1979 Indian Designs from Ancient Ecuador.Dover Publications, New York.Available from:<strong>IUCN</strong> Publications Services Unit219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 ODL, UK or<strong>IUCN</strong> Communications and Corporate Relations DivisionRue Mauverney 28, CH-1196 Gland, SwitzerlandThis book presents case studies in environmental communication and<strong>education</strong> by non government organizations (NGO) and governments. Theideas presented in <strong>the</strong> papers are those of <strong>the</strong> authors. Most of <strong>the</strong> paperswere presented at <strong>the</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union, GeneralAssembly workshop in Buenos Aires in January 1994 organised by <strong>the</strong>Commission on Education and Communication. A few papers have beenadded, those of John Smyth, Joy Palmer, and co-authors Agnes Gomis andFrits Hesselink. The <strong>IUCN</strong> Commission on Education and Communicationpresents <strong>the</strong>se examples <strong>to</strong> encourage planning and management of<strong>education</strong>al programmes by both governments and NGO. Advocating <strong>the</strong>effective use of <strong>education</strong> and communication as an instrument ofenvironmental policy is part of <strong>the</strong> mission of <strong>the</strong> Commission.The presentation of material in this document and <strong>the</strong> geographicaldesignations employed do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoeveron <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>IUCN</strong> or of o<strong>the</strong>r participating organisations concerning <strong>the</strong>legal status of any country, terri<strong>to</strong>ry or area, or concerning <strong>the</strong> delimatationof its frontiers or boundaries.Printed on chlorine free paper from sustainably managed <strong>for</strong>estsiv

ContentsAcknowledgementsForewordvviiPart 1: Some bases <strong>for</strong> planning <strong>education</strong> and communicationInfluences on pro-environmental practicesJoy Palmer 3Behaviour, social marketing and <strong>the</strong> environmentWilliam A. Smith 9A basis <strong>for</strong> environmental <strong>education</strong> in <strong>the</strong> SahelRaphael Ndiaye 21Communication an instrument of government policyAgnes Gomis, Frits Hesselink 29Part 2: Lessons from NGO projectsSeabird conservation on <strong>the</strong> North Shore of <strong>the</strong> Gulf ofSt. Lawrence: The effects of <strong>education</strong> on attitude andbehaviour <strong>to</strong>wards a marine resourceKathleen A. Blanchard 39Environmental <strong>education</strong> programmes <strong>for</strong> naturalareas: a Brazilian case studySuzana M. Padua 51Addressing urban issues through environmental <strong>education</strong>Shyamala Krishna 57The CAMPFIRE programme in Zimbabwe: changes ofattitudes and practices of rural communities<strong>to</strong>wards natural resourcesTaparendava N. Maveneke 66<strong>IUCN</strong> in environmental <strong>education</strong> in western Africaand <strong>the</strong> SahelMonique Trudel 74A matter of motivationIbrahim Thiaw 84Education and communication support <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>establishment of protected area systemsRutger-Jan Schoen 87v

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Part 3: From NGO <strong>to</strong> government national strategies:Country experiencesCanada: National Environmental Citizenship InitiativeT. Christine Hogan 95The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands: Inter-departmental cooperation onenvironmental <strong>education</strong>Peter Bos 103Scotland: Developing a national strategy<strong>for</strong> environmental <strong>education</strong>John C. Smyth 111Spain: The coordination of environmental <strong>education</strong>Susana Calvo 120Australia: Community involvement in conservationof biological diversityChris Mobbs 125Australia: Education and extension:Management’s best strategy <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great BarrierReef Marine ParkDonald J. Alcock 134Nepal: Environmental <strong>education</strong> and awareness aselements of <strong>the</strong> National Conservation StrategyBadri Dev Pande 143Zambia: Environmental <strong>education</strong>Juliana Chileshe 149Ecuador: Raising environmental awarenessMarco Encalada 155Notes on <strong>the</strong> Contribu<strong>to</strong>rs 165vi

Acknowledgements<strong>Planning</strong> Education <strong>to</strong> Care <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earth is based on papers presented at <strong>the</strong><strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union - General Assembly workshop“Changing Attitudes and Practices” held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, inJanuary 1994. The workshop was organised by <strong>the</strong> Commission onEducation and Communication with support from <strong>the</strong> United NationsEducational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and <strong>the</strong>Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries:Department Nature, Forests, Landscape and Wildlife.Funds <strong>for</strong> editing and printing this book have been provided principally by<strong>the</strong> Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) - from Danishfunding of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> environmental <strong>education</strong> programme - and by <strong>the</strong>United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).Good will, collaboration and a ready giving of time and expertise arecharacteristic of <strong>IUCN</strong> commissions. This book happened because oneCommission member, Dr Joy Palmer, of Durham University, UK, <strong>to</strong>ok onvoluntarily <strong>the</strong> original editing and selection of papers. Thanks are due <strong>to</strong>Lynn Carring<strong>to</strong>n and Ann Scott of <strong>the</strong> University of Durham <strong>for</strong> typingsubstantial portions of <strong>the</strong> manuscript, <strong>to</strong> Cecilia Nizzola, <strong>IUCN</strong>, <strong>for</strong> hercontributions <strong>to</strong> typing and <strong>to</strong> supporting <strong>the</strong> Commission’s work, and <strong>to</strong>An<strong>to</strong>n Goldstein who voluntarily scanned and corrected <strong>the</strong> original articlesduring his holidays.The authors, many of <strong>the</strong>m members of <strong>the</strong> Commission, have workedpatiently and supportively with us on <strong>the</strong>ir articles as <strong>the</strong> book has takenshape. Frits Hesselink, as <strong>the</strong> Commission’s chairperson, has been a driving<strong>for</strong>ce in positioning its work in <strong>the</strong> area of strategic planning andmanagement of environmental communication and <strong>education</strong>.Thanks are due <strong>to</strong> Anthony Curnow <strong>for</strong> his concise edi<strong>to</strong>rial style, and <strong>to</strong>Morag White of <strong>IUCN</strong> <strong>for</strong> managing <strong>the</strong> production process.British Airways sponsored travel between England and Geneva <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>purpose of consultation and planning of <strong>the</strong> book. The airline’s support ofconservation activities in this way is gratefully acknowledged.The <strong>IUCN</strong> environmental <strong>education</strong> programme, which assists <strong>the</strong>Commission on Education and Communication in its work, has been in <strong>the</strong>main supported by <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Ministry of Agriculture, NatureManagement and Fisheries: Department Nature, Forests, Landscape andWildlife from 1991-1993, and from 1994-1995 in conjunction withDANIDA. The support of <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands and Danish governments isgreatly appreciated.vii

ForewordMy introduction <strong>to</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> - The World Conservation Union, was at <strong>the</strong>General Assembly held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in January 1994. I hadjust been designated Direc<strong>to</strong>r General of <strong>the</strong> Union. I found it enormouslystimulating <strong>to</strong> join delegates from all parts of <strong>the</strong> world - from governmentsand non-government organisations alike - as <strong>the</strong>y debated, discussed andplanned ways <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong> and its peoples. Their energy, sense ofcommitment, and enthusiasm impressed me and fired up my own enthusiasm<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> job be<strong>for</strong>e me.Three months later, in assuming office as Direc<strong>to</strong>r-General, I <strong>to</strong>ok up <strong>the</strong>challenge of working <strong>to</strong> <strong>for</strong>ge that energy and commitment in<strong>to</strong> a morepowerful <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> conservation. This meant fur<strong>the</strong>r stimulating <strong>the</strong> alliancebetween <strong>IUCN</strong> members, <strong>the</strong> voluntary expert networks we callCommissions, and <strong>the</strong> secretariat. It seems very apparent that only when<strong>the</strong>se three “pillars” are interlocking, that we have <strong>the</strong> underpinning <strong>the</strong>Union needs <strong>to</strong> take on <strong>the</strong> daunting environmental tasks we have be<strong>for</strong>e us.I feel strongly that if we are <strong>to</strong> stand a chance of addressing <strong>the</strong> world’scomplex environmental problems, we have <strong>to</strong> motivate public participationin caring <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>, while meeting <strong>the</strong> development needs of people. It isnow universally recognised that <strong>education</strong> and communication are essential<strong>to</strong>ols in making this ideal of “conservation and sustainable development” areality and a part of popular thinking, acting and doing. That, at least, is <strong>the</strong><strong>the</strong>ory. As always, <strong>the</strong> practice is not so obvious.The interface between <strong>the</strong>ory and practice is exactly what <strong>IUCN</strong> was lookingat in Buenos Aires, where workshops provided an opportunity <strong>to</strong> share andanalyse international experiences based on <strong>the</strong> principles embodied inCaring <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earth, A Strategy <strong>for</strong> Sustainable Living. To explore one of<strong>the</strong>se principles, that we need <strong>to</strong> change personal attitudes and practices inorder <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>, <strong>IUCN</strong>’s Commission on Education andCommunication organized a workshop entitled “Changing attitudes andpractices”. This book is a direct result of <strong>the</strong> papers presented at thatworkshop.The book has three sections: <strong>the</strong> first seeks <strong>to</strong> provide some bases <strong>for</strong>planning <strong>education</strong> and communication, <strong>the</strong> second looks at NGO <strong>education</strong>programmes, and <strong>the</strong> third at planning <strong>education</strong> at <strong>the</strong> national level.Thus, <strong>the</strong>se sections play <strong>to</strong> one of <strong>IUCN</strong>’s unique strengths: its ability <strong>to</strong>bring <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r government and NGO organisations behind <strong>the</strong> banner ofconservation. No o<strong>the</strong>r organisation has NGOs, national governments, andgovernmental organisations as its members. But in order <strong>to</strong> get <strong>the</strong>governments and NGOs <strong>to</strong> really work <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r, we must recognize that eachhas different needs and different capacities. While NGOs may be critical ofgovernment action at times - and often rightly so - , <strong>the</strong>y also have much <strong>to</strong>offer governments in a positive sense. NGOs are good facilita<strong>to</strong>rs infostering community participation in environmental work, a role someviii

Forewordgovernments find difficult <strong>to</strong> handle. NGOs are also undertaking numerousenvironmental initiatives throughout <strong>the</strong> world. Governments can learn from<strong>the</strong>se experiences <strong>to</strong> help shape better policies and actions. Likewise,governments have a specific role, born of <strong>the</strong>ir resources and accountability<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir citizens, that makes <strong>the</strong>m essential partners in conservation. This wasclearly demonstrated in <strong>the</strong> Australian case study found in this book, where<strong>the</strong> government helped share experiences amongst NGOs and communitygroups, thus fostering more effective action. In short, this book shows thatafter examining <strong>the</strong> various needs and capacities of governments and NGOs,<strong>the</strong> two would do well <strong>to</strong> look <strong>for</strong> more opportunities <strong>to</strong> work in acollaborative way.One example of this comes in <strong>the</strong> area of in<strong>for</strong>mation. Often NGOs needtimely and clear in<strong>for</strong>mation if <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>to</strong> accomplish <strong>the</strong>ir goals.Governments can assist in making this sort of in<strong>for</strong>mation available. InCanada, <strong>to</strong> use ano<strong>the</strong>r example described in <strong>the</strong> book, <strong>the</strong> governmentsupported a programme <strong>to</strong> prepare <strong>the</strong> sort of environmental in<strong>for</strong>mation thatwould be needed by a model “environmental citizen.” Recognising that <strong>the</strong>ycould not educate on <strong>the</strong>ir own, <strong>the</strong> government <strong>for</strong>med partnerships, both <strong>to</strong>prepare material and, more importantly, <strong>to</strong> use it in <strong>education</strong> programmes.The results of this work are fascinating. I would encourage bothgovernments and NGOs <strong>to</strong> extract <strong>the</strong> lessons from this case study.Ano<strong>the</strong>r clear message of this publication is that <strong>education</strong> can help bringabout participation and thus merits fur<strong>the</strong>r investment if we are <strong>to</strong> seeprogress <strong>to</strong>wards environmental goals. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, governments cansupport environmental <strong>education</strong> through policies and by providing funding.As an example, <strong>to</strong> give environmental <strong>education</strong> a boost, six Ministries in <strong>the</strong>Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands committed funds <strong>to</strong> prepare a strategy which would helpintegrate environment and sustainable development in<strong>to</strong> both schooling andnon <strong>for</strong>mal <strong>education</strong>. Again, this approach is illuminating.On <strong>the</strong> non-governmental side, <strong>the</strong> fac<strong>to</strong>rs that have led <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> success ofNGO programmes are documented in a group of studies found in <strong>the</strong> secondsection of this publication. A conclusion that may be drawn from thosestudies is that NGOs have a critical role <strong>to</strong> play in creating environmentalawareness and in working with communities <strong>to</strong> ensure that <strong>the</strong> sustainableuse of natural resources can be used as a basis of development. In Canada,<strong>for</strong> example, attitudes and behaviour <strong>to</strong>wards a marine resource - seabirds inthis case - were changed as <strong>the</strong> result of an <strong>education</strong> programme developedby a private foundation working in close cooperation with <strong>the</strong> CanadianWildlife Service.These NGO studies emphasise that <strong>the</strong> success of a communication strategydepends on how well one “does one’s homework.” It is important <strong>to</strong> knowwhat has <strong>to</strong> be changed and why, be<strong>for</strong>e looking at <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>ols that can be used<strong>to</strong> bring that change about. For this reason, research is an essential part ofany <strong>education</strong>al programme. It not only helps provide an understanding of<strong>the</strong> people’s perceptions and practices, but it can also shed some light on <strong>the</strong>barriers that stand in <strong>the</strong> way of change. This message is reiterated in studiesfrom Zambia, <strong>the</strong> Sahel, and North America.ix

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>O<strong>the</strong>r case studies presented show that it is necessary <strong>to</strong> work on <strong>the</strong>structural fac<strong>to</strong>rs that may impede change in behaviour. For example, inorder <strong>for</strong> communities <strong>to</strong> derive direct financial benefits from naturalresources, as is <strong>the</strong> case of communities in Zimbabwe, NGOs have needed <strong>to</strong>contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> establishment of new laws and regulations. At <strong>the</strong> sametime, through <strong>education</strong>al programmes, NGOs rein<strong>for</strong>ce local democracy in<strong>the</strong> management and conservation of resources.Educational programmes often require a supporting infrastructure. A wastemanagement project in India, <strong>for</strong> instance, needed local government support<strong>to</strong> provide containers, and sites <strong>for</strong> composting. The waste collectionworkers had <strong>to</strong> be trained. Success lay in working with all <strong>the</strong> concernedsec<strong>to</strong>rs and community groups from <strong>the</strong> planning stage onwards.Additionally, <strong>the</strong> case studies collected herein show that evaluation needs <strong>to</strong>be an integral part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>education</strong>al process. Often, <strong>the</strong> results ofevaluations can provide powerful arguments <strong>for</strong> expanding <strong>education</strong>alef<strong>for</strong>ts when <strong>the</strong>y demonstrate how <strong>the</strong>se ef<strong>for</strong>ts have led <strong>to</strong> an obviousimprovement in <strong>the</strong> environment. The importance of evaluation is revealedby <strong>the</strong> programme on seabirds in Canada, or by <strong>the</strong> case study from Brazil,where communities were shown <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> a natural area as a result of<strong>education</strong>. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, work in Ecuador has shown that raisingawareness, and even knowledge, may alone not lead people <strong>to</strong> change <strong>the</strong>irpractice. A more integrated strategy is suggested.All in all, a major lesson that can be drawn from <strong>the</strong> case studies in this bookis that we all need <strong>to</strong> reflect, learn and profit from experience. Sharinglessons learned in planning and managing <strong>education</strong> and communication is ameans of improving our work in <strong>the</strong> area of <strong>education</strong> and communication.Apart from that, if we are indeed <strong>to</strong> have people take responsibility <strong>for</strong>environment and sustainable development, <strong>education</strong> and communication areimportant means at our disposal. Governments and NGOs both haveimportant roles <strong>to</strong> play, <strong>the</strong> challenge is <strong>to</strong> ensure that <strong>the</strong>y work <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r andthat, in both cases, <strong>the</strong>ir effectiveness and reach are increased. For thisreason and in this hope, we are pleased <strong>to</strong> help share <strong>the</strong>se studies.David McDowellDirec<strong>to</strong>r General <strong>IUCN</strong>x

Part 1Some bases <strong>for</strong> planning <strong>education</strong> andcommunication

Pllanning <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Influences on pro-environmental practicesJoy A. PalmerAbstractCertain experiences are shown <strong>to</strong> have influenced pro-environmentalbehaviours in a study of UK environmental educa<strong>to</strong>rs. The results arecompared with a similar study in <strong>the</strong> USA. Have schools beeninfluential? What is <strong>the</strong> role of family and outdoor activities? Theimplications of <strong>the</strong> study <strong>to</strong> policies and practices in <strong>the</strong> UK aredescribed.Those responsible <strong>for</strong> organising and implementing <strong>education</strong> andcommunication programmes which are intended <strong>to</strong> help people learn aboutand <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment should certainly know something aboutlearning experiences that produce active and in<strong>for</strong>med minds. This chapterwill attempt <strong>to</strong> give some understanding of <strong>the</strong> influences and experienceswhich develop pro-environmental behaviours.A research study in <strong>the</strong> United States by Tanner (1980) highlighted lifeexperiences that produce adults who are in<strong>for</strong>med about and activelypromote environmentally positive behaviour. Conservationists were asked <strong>to</strong>identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mative influences that led <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> choose conservation work.Youthful experiences of <strong>the</strong> outdoors and of pristine environments emergedas <strong>the</strong> most dominant influence, supporting Tanner’s hypo<strong>the</strong>sis (1974a,1974b) that children must first come <strong>to</strong> know and love <strong>the</strong> natural worldbe<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong>y can become concerned with its <strong>care</strong>.Following on from this work, Palmer (1993) generated data about <strong>for</strong>mativeexperiences and environmental concern from a larger sample of adults.This study focused on environmental educa<strong>to</strong>rs - a group of active andin<strong>for</strong>med citizens who know about and <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment in <strong>the</strong>iradult lives. An outline of <strong>the</strong> study was sent <strong>to</strong> members of <strong>the</strong> NationalAssociation <strong>for</strong> Environmental Education in <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom. Theywere asked <strong>to</strong> provide <strong>the</strong>ir age, gender, details of <strong>the</strong>ir demonstration ofpractical concern <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment, and an au<strong>to</strong>biographical statementidentifying <strong>the</strong> experiences which had led <strong>to</strong> that concern. They were alsoasked <strong>to</strong> recount what <strong>the</strong>y considered <strong>to</strong> be <strong>the</strong>ir most significant lifeexperience and <strong>to</strong> write a statement indicating which, if any, of <strong>the</strong> years of<strong>the</strong>ir lives were particularly memorable in <strong>the</strong> development of positiveattitudes <strong>to</strong>wards <strong>the</strong> environment. Only <strong>the</strong> aims and purposes of <strong>the</strong>research were notified <strong>to</strong> participants so that <strong>the</strong>y were able <strong>to</strong> providecompletely original responses that had not been biased by suppliedexamples.3

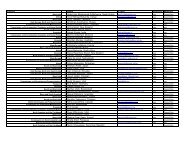

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Of 232 useable responses, 102 came from men and 130 from women.Categories of response were coded and only explicit or prominentreferences in individual statements were scored. Responses were nei<strong>the</strong>rweighted nor ranked between or within statements. Weighting suggested by<strong>the</strong> subject - identification of a single most important influence - was,however, noted and included in <strong>the</strong> analysis.Thirteen major categories of response were established, some with subcategories,in <strong>the</strong> final analysis (Table 1). “Outdoors” included threesubstantial sub-categories: childhood outdoors (97 respondents), outdooractivities (90), and wilderness/solitude (24). The 97 references <strong>to</strong> childhoodoutdoors included details of growing up in rural areas, holidays in <strong>the</strong>outdoors and childhood participation in outdoor pastimes.Table 1. Number of Subjects Identifying with Each Major Category ofResponse (n=232)Number %Outdoors 211 91Education / Courses 136 59Parents / Close relatives 88 38Organisations 83 36TV / Media 53 23Friends / o<strong>the</strong>r individuals 49 21Travel abroad 44 19Disasters / negative issues 41 18Books 35 15Becoming a parent 20 9Keeping pets / animals 14 6Religion / God 13 6O<strong>the</strong>rs 35 15Total 232“Education/courses” referred <strong>to</strong> two sub-categories: higher <strong>education</strong> oro<strong>the</strong>r courses taken as an adult (85 respondents) and school courses (51).Twenty-three subjects reported that school programmes had no influence on<strong>the</strong>m; o<strong>the</strong>rs described courses, particularly at higher and secondary<strong>education</strong> levels, as being very significant.The third largest category of response - “parents and close relatives” (88respondents) - and <strong>the</strong> separate category - “friends and o<strong>the</strong>r individuals”(49) - demonstrated that ideas and examples set by o<strong>the</strong>rs are critical<strong>for</strong>mative influences.The role of organisations in developing environmental concern was also4

Influences on pro-environmental practicesshown <strong>to</strong> be important. This category (83 respondents) was sub-dividedbetween <strong>the</strong> influence of youth organisations such as scouting, guiding andsimilar programmes (28), and influence of membership of adul<strong>to</strong>rganisations concerned with environmental matters and “green” thinking(55).O<strong>the</strong>r main categories of response were “TV/media”, “Books” (notablyRachel Carson’s “Silent Spring”), “Foreign travel”, “Negative issues”(notably environmental catastrophes, nuclear threats, cruelty <strong>to</strong> animals,pollution), “Becoming a parent”, “Keeping animals”, and “Religion”.Significant responses scoring less than 10 were grouped in “O<strong>the</strong>rs” (35respondents) which included such responses as living in a large city, healthissues, music, poetry, death, personal heritage and personal networking.Eighty of <strong>the</strong> 232 respondents identified <strong>the</strong>ir single most important lifeexperience or influence. The results are given in Table 2.Table 2. Number of Subjects Naming Single Most Important Influence(n=80)Number %Outdoors 23 29Education / Courses 7 9Parents / Close relatives 21 26Organisations 5 6TV / Media 2 2Friends / o<strong>the</strong>r individuals 4 5Travel abroad 5 6Disasters / negative issues 4 5Books 3 4Becoming a parent 1 1Keeping pets / animals 0 0Religion / God 1 1O<strong>the</strong>rs 4 5Total 80The data were analysed more finely <strong>to</strong> examine differences in responseacross <strong>the</strong> age groups, and <strong>to</strong> establish correlations between <strong>the</strong> fac<strong>to</strong>rs ofresponse. The positive experiences of nature and <strong>the</strong> countryside inchildhood, it was found, were much more commonly identified in <strong>the</strong>older age groups than in <strong>the</strong> youngest. The figures <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> enjoyment ofoutdoor activities in adult life and interest in gardening, agriculture andhorticulture gave similar results. Those who mentioned <strong>the</strong>ir employmentalso showed clear differences. Less than 10 percent of <strong>the</strong> under-30 agegroup referred <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> influence of <strong>the</strong>ir work; this aspect of life wasmentioned by 74 percent of <strong>the</strong> over-50s. The influence of books and5

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>papers which deal with environmental issues emerged in 33 percent of <strong>the</strong>life accounts of <strong>the</strong> under-30s, but in only 11 percent of those supplied by<strong>the</strong> over-50s.The types of organisation that have an influence provided ano<strong>the</strong>rinteresting difference. Those dealing with <strong>the</strong> natural world, such asNaturalist Trust and <strong>the</strong> Royal Society <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Protection of Birds, wereconsidered more influential by <strong>the</strong> oldest age group; organisationsconcerned with <strong>the</strong> danger of human impact on <strong>the</strong> global environment -<strong>for</strong> example Greenpeace and CND - are more influential with youngercitizens.A correlation between individual fac<strong>to</strong>rs was only possible with <strong>the</strong> mostimportant responses. Two significant correlations (at 1 percent level) werefound: one between childhood experiences of nature and <strong>the</strong> influence ofclose family and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r between childhood experience of nature andwork-related influences.This study confirms <strong>the</strong> findings of Tanner that childhood experience of <strong>the</strong>outdoors is <strong>the</strong> single most important fac<strong>to</strong>r in developing personal concern<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment. In <strong>the</strong> Palmer study, subjects in all <strong>the</strong> age groupsmade extensive and detailed references <strong>to</strong> early childhood days of exploring<strong>the</strong> natural world and deriving sensory experiences in <strong>the</strong> open air. Theyalso stressed <strong>the</strong> crucial importance of parents, teachers and o<strong>the</strong>r adults.Many statements testified <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> significant impact of <strong>the</strong> knowledge andexample of o<strong>the</strong>rs on <strong>the</strong> early learning of respondents.The impact of <strong>for</strong>mal programmes concerning <strong>the</strong> environment in <strong>the</strong> fieldof higher <strong>education</strong> is confirmed by <strong>the</strong> data of <strong>the</strong> study, and this isencouraging. The majority of respondents citing <strong>education</strong> as a single mostimportant influence were writing about degree-level courses. O<strong>the</strong>rs in thisgroup wrote about advanced self-chosen (A-level examination) courses inschool.One of <strong>the</strong> most disturbing findings, perhaps, is <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal lack of referencesin <strong>the</strong> study data <strong>to</strong> a school course below A-level as a single mostimportant influence. Moreover, of <strong>the</strong> 51 respondents citing school lessonsor courses as a significant influence, 38 referred specifically <strong>to</strong> A-levelcourses and related field work. A number of respondents made clearstatements <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> effect that <strong>for</strong>mal school programmes had little or even noinfluence on <strong>the</strong>ir thinking in relation <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment.Studies such as those of Tanner and Palmer clearly raise important issues<strong>for</strong> debate and action by those who establish policy and provideenvironmental <strong>education</strong> (EE) programmes at all levels. Policy-makers and<strong>education</strong>alists alike need <strong>to</strong> take serious account of <strong>the</strong> need <strong>to</strong> give youngpeople <strong>the</strong> opportunity <strong>to</strong> have a wealth of positive experiences in outdoorhabitats.Financial economies in <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom are <strong>for</strong>cing environmental andoutdoor <strong>education</strong> centres <strong>to</strong> close down. This is possibly <strong>the</strong> case in o<strong>the</strong>r6

Influences on pro-environmental practicescountries. Environmental programmes may be marginalized in <strong>the</strong> processof curriculum re<strong>for</strong>m. Such developments tend <strong>to</strong> reduce <strong>the</strong> number ofwell qualified and caring environmental educa<strong>to</strong>rs and curriculumdevelopment staff.These trends have serious policy implications. The data ga<strong>the</strong>red in <strong>the</strong>Palmer project could have a crucial influence on <strong>the</strong> people responsible <strong>for</strong>school budget preparation and curriculum development programmes, byproviding <strong>the</strong> understanding that positive experiences in <strong>the</strong> environmentare vital <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> development of concern <strong>for</strong> it.It seems appropriate in <strong>the</strong> light of <strong>the</strong> study <strong>to</strong> reconsider <strong>the</strong> content ofcourses <strong>for</strong> intending teachers at all levels (not only those concerned withadvanced examination work). All teacher trainees must be given not only<strong>the</strong> subject-matter knowledge of environmental issues but must alsounderstand <strong>the</strong> ways in which this may effectively be passed on <strong>to</strong> pupils ina classroom. In <strong>education</strong>al terms, knowledge of <strong>the</strong> pedagogic content isas important as knowledge of <strong>the</strong> subject itself.Finally, <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong> sense of “ownership” has <strong>to</strong> be stressed.Many of <strong>the</strong> au<strong>to</strong>biographical accounts make this obvious. If young people- and indeed adults - feel that <strong>the</strong>y belong <strong>to</strong> a place or a project, andperceive <strong>the</strong> direct relevance of <strong>the</strong> environment <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own lives, <strong>the</strong>ngenuine <strong>care</strong>, concern and a desire <strong>to</strong> take positive action will result. Surely<strong>the</strong> development of such a sense should underlie <strong>the</strong> aims of programmes ofenvironmental <strong>education</strong>.Explana<strong>to</strong>ry note:The study described in this chapter is <strong>the</strong> first phase of an extendedinvestigation in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> development of peoples’ concern <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environmententitled: Emergent Environmentalism. This is an international study,currently funded by <strong>the</strong> Economic and Social Research Council in <strong>the</strong>United Kingdom (<strong>for</strong> work in England and <strong>the</strong> United States) and <strong>the</strong>British Council (in Slovenia). Data on <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mative experiences ofenvironmental educa<strong>to</strong>rs now being collected in <strong>the</strong> United States andCanada will significantly enlarge <strong>the</strong> research base.Ano<strong>the</strong>r aspect of <strong>the</strong> overall project (ongoing at <strong>the</strong> University ofDurham) involves a study of <strong>the</strong> environmental knowledge base of younglearners. In this phase we are considering what children know andunderstand about selected environmental issues as and when <strong>the</strong>y startschool and how that knowledge develops during <strong>the</strong> first two <strong>to</strong> three yearsof <strong>for</strong>mal <strong>education</strong>.The overall project will generate data with far-reaching implications <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>design and development of EE programmes. These data will also serve as asound academic research base with relevance <strong>for</strong> all those engaged in <strong>the</strong>planning and implementation of policy at both national and localcommunity levels.7

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>ConclusionUnderstanding <strong>the</strong> way learning occurs and what stimulatesenvironmental behaviours is as important as environmentalin<strong>for</strong>mation. The study showed that childhood outdoor activities wereinfluential in determining <strong>the</strong> commitment of environmental educa<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment. Yet, primary <strong>education</strong> was not influential. Thissuggests that primary <strong>education</strong> should provide outdoor learningexperiences. "A" level and tertiary <strong>education</strong> was very influential, aswere parents and close relatives. Teacher training needs <strong>to</strong> reflect<strong>the</strong>se facts, providing not only environmental in<strong>for</strong>mation but alsohow this can be most effectively taught <strong>to</strong> bring about commitmentand action.ReferencesPalmer, J.A. 1993. Development of Concern For The Environment andFormative Experiences of Educa<strong>to</strong>rs, Journal of Environmental Education,Vol.24, No.3, pp.26-31.Tanner, T. 1974a. Conceptual and Instructional Issues in EnvironmentalEducation Today. Journal of Environmental Education, No.5(4), pp.48-53.Tanner, T. 1974b. Ecology, Environment and Education. Lincoln, NE:Professional Educa<strong>to</strong>rs Publications.Tanner, T. 1980. Significant Life Experiences, Journal of EnvironmentalEducation, Vol.11, No. 4 pp 20-24.8

Behaviour, social marketing and <strong>the</strong> environmentWilliam A. SmithAbstractThe Applied Behavioural Change (ABC) Framework, developed by<strong>the</strong> Academy <strong>for</strong> Educational Development, USA, helps programmemanagers <strong>to</strong> design, develop and evaluate interventions which lead <strong>to</strong>change of behaviour on a large scale. It integrates lessons drawn fromcommunity participation, communication planning, social marketingand behavioural science. ABC gives managers an accurate idea of <strong>the</strong>perceptions of communities and individuals <strong>to</strong>wards proposedalternative courses of action. It assists development agents faced with<strong>the</strong> increasingly complex task of helping communities decide howbest <strong>to</strong> protect <strong>the</strong> environment by assuring benefits now, as well as<strong>for</strong> generations in <strong>the</strong> future.IntroductionEnvironmental protection is among <strong>the</strong> greatest challenges facing socialscience <strong>to</strong>day. In meeting this challenge, we have <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>ols both <strong>to</strong> improveenvironmental sustainability and at <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>to</strong> contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>understanding of how our species interacts with <strong>the</strong> environment.The growing debate between a “behaviour change model” and a“participa<strong>to</strong>ry model” is wasteful and distracting. We do not need <strong>to</strong> choosebetween behaviour and participation or between behaviour and criticalconsciousness. We need both <strong>the</strong> full and conscious participation of <strong>the</strong>people whose behaviour must change if <strong>the</strong> environment is <strong>to</strong> survive, and<strong>the</strong> application of sound social and environmental science <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> design ofprogrammes which will help those people <strong>to</strong> make workable changes in <strong>the</strong>irbehaviour. We have several models <strong>for</strong> integrating participation andbehaviour that have already proven successful.When a woman in Africa cuts <strong>the</strong> last remaining local tree <strong>for</strong> fuelwood, sheis at <strong>the</strong> end of a long chain of environmentally unsound behaviours. Toomany people have been living in <strong>to</strong>o consumptive a style <strong>to</strong> sustain <strong>the</strong><strong>for</strong>ests upon which her people depend. If <strong>to</strong>o many individuals of a singlespecies behave in a way incompatible with <strong>the</strong> ecosystem, that ecosystemwill die.Our future rests on a belief that human behaviour matters and that humanbehaviour can change <strong>to</strong> more sustainable patterns. As humans, we appear9

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>not only able <strong>to</strong> recognize <strong>the</strong> damage we are doing but also, at least inisolated cases, <strong>to</strong> change reproductive and consumptive behaviours <strong>to</strong>wardsmore sustainable patterns. In putting <strong>the</strong> question - how best <strong>to</strong> influencehuman behaviour <strong>to</strong> be more environmentally sound? - we move out of <strong>the</strong>realm of philosophy in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> arena of empirical science.Unique behavioural challengeEnvironmental protection is a unique behavioural challenge <strong>for</strong> severalreasons:• Highly complex inter-relationships. (Fuelwood consumptionaffects <strong>for</strong>ests and influences biodiversity, which influencesjobs and food supply, which influences pesticide use, whichinfluences human and environmental health etc.). Behaviouralchanges in any one area often fail <strong>to</strong> have significant positiveeffects elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> chain, while significant change in asingle behaviour can produce unanticipated and sometimesnegative effects on o<strong>the</strong>r elements.• Environmental science is still in development. The speed ofchanging knowledge leaves <strong>the</strong> public sceptical and makes<strong>the</strong> environmentalists vulnerable <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir opponents.• Delayed benefits compete against immediate gain.Environmental problems often have consequences spreadacross generations and lose immediacy <strong>for</strong> a public facingurgent daily issues. Competing behaviours on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r handoffer jobs, income, and quick rewards.• Environmental problems are often framed on a global scale,giving <strong>the</strong> impression <strong>to</strong> individuals that <strong>the</strong>y can do little <strong>to</strong>help. They deny <strong>the</strong>ir own ability <strong>to</strong> change or engage inpiecemeal ef<strong>for</strong>ts.• A politicized North-South debate that influences publicperceptions and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e behaviour. In developingcountries, policy-makers and <strong>the</strong> public are offended byWestern insistence that <strong>the</strong>y must save <strong>the</strong> environment at<strong>the</strong> expense of jobs and rapid industrial development, and<strong>for</strong>ego <strong>the</strong> benefits of consumption known in <strong>the</strong> West. TheNorth criticizes <strong>the</strong> South <strong>for</strong> irresponsibility and <strong>the</strong> Southresponds with accusations of hypocrisy against <strong>the</strong> North.Environmental behaviours never<strong>the</strong>less are changing, and <strong>the</strong> presentgeneration is more environmentally active than any o<strong>the</strong>r in human his<strong>to</strong>ry.Social science helps explain why and how <strong>the</strong>se changes are occurring.The environmentalist in search of a key <strong>to</strong> human behaviour shouldstart with proven psychological determinants, such as:10

Social marketing• Perceived benefits. What advantage do people think <strong>the</strong>y willget by adopting a new practice?• Perceived barriers. What do people worry about, think <strong>the</strong>ywill have <strong>to</strong> give up, suffer, put up with or overcome in order<strong>to</strong> get <strong>the</strong> benefit <strong>the</strong>y decide <strong>the</strong>y want from a new action?• Social norms. Whom does <strong>the</strong> audience <strong>care</strong> about and trus<strong>to</strong>n this <strong>to</strong>pic, and what do <strong>the</strong>y think that person/group wants<strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> do?• Skills. Is <strong>the</strong> audience able <strong>to</strong> per<strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong> new actionwithout embarrassment or without failing?Applied Behavioural Change (ABC) FrameworkThe Academy <strong>for</strong> Educational Development (AED) has developed aframework <strong>for</strong> programme design and implementation that offers a way <strong>to</strong>translate social science in<strong>to</strong> practical programmes that help people <strong>to</strong> behavein environmentally sound ways. This is <strong>the</strong> Applied Behavioural Change(ABC) Framework.The ABC Framework is intended <strong>to</strong> help programme managers <strong>to</strong> design,develop and evaluate interventions which lead <strong>to</strong> large-scale behaviourchange. It helps managers who wish <strong>to</strong> influence human behaviour <strong>to</strong> answerthree practical questions:• What do I do first?• What do I manage at each stage <strong>to</strong> ensure a comprehensiveprogramme?• What miles<strong>to</strong>nes do I moni<strong>to</strong>r and evaluate?The framework has three components: participa<strong>to</strong>ry programmedevelopment (a sequential process <strong>for</strong> organizing and conducting large-scalebehaviour change interventions); social marketing (a strategic system <strong>for</strong>people centred decision making); and a behavioural constellation (whichdescribes <strong>the</strong> priority behavioural targets <strong>to</strong> assess, moni<strong>to</strong>r and evaluate).Participa<strong>to</strong>ry programme developmentProgramme development is built on <strong>the</strong> premise that people must shape andcontrol <strong>the</strong>ir own trans<strong>for</strong>mation and that participa<strong>to</strong>ry processes bestachieve this goal.The process is cyclical, constantly reframing interventions <strong>to</strong> correctmistakes or <strong>to</strong> address changes in <strong>the</strong> target audience. All systemsintermingle participa<strong>to</strong>ry research with programme action (fig. 1).The first step is <strong>to</strong> assess <strong>the</strong> problem, <strong>the</strong> community’s current behaviour,11

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>knowledge and attitude <strong>to</strong>wards <strong>the</strong> problem, and <strong>the</strong> delivery mechanismsavailable <strong>to</strong> influence that community.AudienceAssessImplementPlanPretestFigure 1. The Programme Development Process.The next move is <strong>to</strong> plan a strategic intervention that integrates products,services, messages, and support <strong>to</strong> a specific audience through variouschannels in a way that is attractive, accessible and persuasive. This is bestdone by <strong>the</strong> community affected working with scientists and behaviouralspecialists.The products, materials and tactics selected <strong>for</strong> dissemination through face<strong>to</strong>-face,community, print and mass media channels are <strong>the</strong>n pre-tested.The fourth stage is <strong>to</strong> implement <strong>the</strong> delivery of products, services, materials,messages and support through appropriate channels.The circle is closed by Step 5, in which <strong>the</strong> original Step 1 is trans<strong>for</strong>medin<strong>to</strong> continuous moni<strong>to</strong>ring and modification of inputs so as <strong>to</strong> addresschanging audience needs.Social marketingSocial marketing is a management system based on <strong>the</strong> concept of exchange.It holds that people take action in exchange <strong>for</strong> benefits. Programmemanagers must identify <strong>the</strong> existing benefits <strong>for</strong> a particular audience and aspecific behaviour, <strong>the</strong> possible new benefits and barriers, and how <strong>to</strong> offer achoice that provides more benefits and fewer barriers. At every stage it is <strong>the</strong>community and <strong>the</strong> individual that determine which benefits and barriers aremost important.Building a better product/service, making it more accessible, lowering itscost, or persuading people <strong>to</strong> appreciate its benefits over those of <strong>the</strong>competition are ways of making such a determination. The centrepiece is <strong>the</strong>target audience and <strong>the</strong> benefits that audience wishes <strong>to</strong> receive <strong>for</strong> adopting12

Social marketingnew behaviours. The process should be fundamentally participa<strong>to</strong>ry andresponsive <strong>to</strong> people’s needs.Social marketing has defined four domains of influence - <strong>the</strong> four Ps:product, place, price, and promotion (fig. 2).ProductPricePlacePromotionFigure 2. The Social Marketing Inputs.The product P represents <strong>the</strong> programme decisions associated with selectingand shaping <strong>the</strong> idea, commodity, behaviour, or service (<strong>the</strong> product) <strong>to</strong> bepromoted. At each process stage, managers must focus on <strong>the</strong> qualities of<strong>the</strong> product which will increase <strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> target audience.Place refers <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> system through which <strong>the</strong> products flow <strong>to</strong> users and <strong>the</strong>quality of service offered where those products are made available. Placefocuses largely on overcoming one important obstacle <strong>to</strong> use: difficulty ofaccess. Place also includes <strong>the</strong> training of providers (community-basedoutreach workers, peers, friends, neighbours, professionals). Socialmarketing focuses attention on <strong>the</strong>ir role as an effective sales <strong>for</strong>ce, stressing<strong>the</strong>ir skills in communication and persuasion.Price refers <strong>to</strong> more than monetary cost. It represents all <strong>the</strong> barriers a personmust overcome be<strong>for</strong>e accepting <strong>the</strong> proposed social product, including lossof status, embarrassment, <strong>the</strong> time lost in adapting <strong>to</strong> a new practice.Promotion - <strong>the</strong> fourth P - includes <strong>the</strong> functions of advertising, publicrelations, consumer promotion, user <strong>education</strong>, counselling, communityorganization and inter-personal support. It also encompasses decisions aboutwhat will be said about <strong>the</strong> behaviour and its benefits, and on <strong>the</strong> channels <strong>to</strong>be used <strong>to</strong> get <strong>the</strong> message across <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> right people at <strong>the</strong> right time.Each P makes an irreplaceable contribution <strong>to</strong> successful behaviouralchange, but <strong>the</strong> proportional role of each in any given situation may vary.The art of successful social marketing is <strong>to</strong> achieve <strong>the</strong> right mix so that13

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>scarce resources may be concentrated <strong>to</strong> overcome <strong>the</strong> most urgentproblems.Programmes have worked best when communication planning and socialmarketing have been combined with <strong>the</strong> behavioural intervention in anintegrated planning framework (fig. 3).AudienceAssessProductImplementPricePromotionPlacePlanPretestFigure 3. Integrated <strong>Planning</strong> Framework.The audience and its existing behaviour are at <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>p of <strong>the</strong> diagram. Theparticipa<strong>to</strong>ry planning process turns counterclockwise over time, movingthrough <strong>the</strong> patterned sequence of assess, plan, pre-test, implement andmoni<strong>to</strong>r. At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> four Ps of <strong>the</strong> social marketing wheelrevolve rapidly within <strong>the</strong> larger participa<strong>to</strong>ry planning wheel, illustratingthat at every programme stage, all four Ps of <strong>the</strong> marketing mix areassessed, planned, pre-tested, implemented and moni<strong>to</strong>red. Thisinteraction of audience, behaviour, planning process and marketingprovides managers with a comprehensive yet practical programmeplanning process adaptable <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> requirements of most behaviour changetasks.Behavioural constellationPeople do not always do what <strong>the</strong>y know <strong>the</strong>y should do. Mo<strong>to</strong>rists “know”<strong>to</strong> car pool, but don’t; many families “know” <strong>to</strong> recycle, but don’t.Fishermen “know” not <strong>to</strong> dynamite coral reefs, but many do. Explaining <strong>the</strong>knowledge-behaviour gap is <strong>the</strong> domain of behavioural science.Between knowledge and behaviour lie specific attitudes <strong>to</strong>ward behaviour,signposts which have played a large part in shaping understanding oflifestyle-related problems.AED has developed a highly selective behavioural constellation or14

Social marketingchecklist of such determinants based on social science <strong>the</strong>ory (fig. 4). Thebehaviour constellation helps identify <strong>the</strong> targets of greatest opportunity<strong>for</strong> change. This is divided in<strong>to</strong> two categories: internal/cognitive fac<strong>to</strong>rs(<strong>for</strong> example, knowledge, attitudes and beliefs) and external/structuralfac<strong>to</strong>rs (<strong>for</strong> example, access <strong>to</strong> services, cost, policy, social influence).Understanding <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong>se determinants in people’s liveshelps programme managers <strong>to</strong> concentrate scarce programme resources onthose fac<strong>to</strong>rs which are most likely <strong>to</strong> promote sustained behaviouralchange.ExternalSocial Economic StatusEpidemiologyAcces <strong>to</strong> ServicePolicyCultural NormsInternalExternalBehavioural ConstellationInternalSpecific <strong>Knowledge</strong>Perceived RisksPerceived Social NormsPerceived ConsequencesSelf-EfficacyFigure 4. Behavioural Constellation: Checklist of determinants of behaviour.The ABC Framework has in <strong>the</strong> last decade helped <strong>to</strong> select those fac<strong>to</strong>rsthat have consistently proved <strong>to</strong> be important in working with differentpopulations across diverse cultural and socio-economic settings.Audience and behaviour dominate <strong>the</strong> ABC Framework (fig. 5). All <strong>the</strong>variables essential <strong>for</strong> designing interventions are present. The framework ispractical and flexible. It does not pretend that all fac<strong>to</strong>rs are equallyimportant, but selects targets of opportunity based on experience and proven<strong>the</strong>ory, and it allows planners <strong>to</strong> use field research with communities <strong>to</strong>select activities tailored <strong>to</strong> an audience, a community, and a specificbehaviour.Recycling behaviour in a national parkThe ABC Framework was used in <strong>the</strong> context of an environmental protectionproject <strong>to</strong> encourage people <strong>to</strong> separate garbage in two public parks at <strong>the</strong>foot of <strong>the</strong> Washing<strong>to</strong>n and Lincoln Memorials in Washing<strong>to</strong>n D.C., in <strong>the</strong>interests of better recycling. The purpose of <strong>the</strong> specific social marketingexercise was <strong>to</strong> assess <strong>the</strong> behavioural characteristic of an existingprogramme.15

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Audience / BehaviourAssess / Moni<strong>to</strong>rProductImplementPricePromotionPlacePlanPre-ContemplationPretestMaintenanceContemplationDecisionMaking ActionFigure 5. Applied Behavioural Changes Framework.Four sub-areas were delineated <strong>for</strong> observation purposes:• near a concession stand where an attractive signboard on <strong>the</strong>importance of recycling had been placed, alongside a clearlymarked container <strong>for</strong> plastic, glass and aluminum plus atraditional garbage bin;• a street corner, not served by <strong>the</strong> concession stand, but witha recycling container and a traditional bin;• a highly congested bus s<strong>to</strong>p in front of <strong>the</strong> Lincoln Memorialwhere <strong>the</strong> same signboard had been placed;• a concession area near <strong>the</strong> Lincoln Memorial with multiplegarbage receptacles, <strong>the</strong> recycling sign and a rest area <strong>for</strong>visi<strong>to</strong>rs.Existing signsThe signboard made three points. It defined <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> public that glassbottles, plastic bottles, foam cups and take-out containers, and aluminumcans should be placed in bins separate from o<strong>the</strong>r garbage (<strong>the</strong> articleswere depicted and <strong>the</strong>re was also an illustration of two young childrenusing <strong>the</strong> recycling container). Secondly, it illustrated <strong>the</strong> technology ofrecycling, and finally it indicated how much garbage is produced on <strong>the</strong>Mall every week.16

Social marketingThe recycling containers displayed <strong>the</strong> symbol of recycling plus <strong>the</strong> words:“plastic, glass, aluminum only”, and two symbols indicating that hot dog andpota<strong>to</strong> chips wrappers were not <strong>to</strong> be thrown in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> can. The garbage binswere of a different size and shape from <strong>the</strong> recycling containers and werelabelled “Trash Only”. There was a third container unlabelled and differentfrom <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two located next <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> concession stand in sub-area D.The hypo<strong>the</strong>sis was that <strong>the</strong> presence of new signs and <strong>the</strong> availability ofrecycling trash containers would lead <strong>to</strong> a high level (80 per cent) of properdisposal of recyclable drink cups and o<strong>the</strong>r recyclable products.The three activities in <strong>the</strong> case study were <strong>to</strong> determine whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sisis accurate (behavioural assessment and direct observation); <strong>to</strong> determinewhich problems in <strong>the</strong> observation areas might be solved by intervention(problem analysis and data assessment); and a brains<strong>to</strong>rming session onpossible interventions <strong>to</strong> correct identified problems (programme planning).Observations were conducted on two days - weekend and weekday - <strong>for</strong> twoperiods of 60 minutes each. Teams of two-three observers worked at eachsite <strong>for</strong> a <strong>to</strong>tal of 12 <strong>to</strong> 15 hours. Observers were trained <strong>for</strong> one hour on how<strong>to</strong> observe and record data.ResultsMost people <strong>to</strong>ok no note of <strong>the</strong> expensive, well-designed and well-placedsigns and did not recycle properly. Observation of <strong>the</strong> area and <strong>the</strong> contentsof <strong>the</strong> bins showed that cups clearly marked as recyclable were almostevenly distributed in <strong>the</strong> recycling and non-recycling containers.One conclusion was that people came <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mall <strong>to</strong> have fun - not <strong>to</strong>recycle. They expected <strong>to</strong> see signs with in<strong>for</strong>mation about <strong>the</strong> monuments<strong>the</strong>y had come <strong>to</strong> see - not about recycling. Ano<strong>the</strong>r conclusion was that<strong>the</strong>re were <strong>to</strong>o many types of garbage bin and <strong>to</strong>o many conflicting labelswhich led those people who tried <strong>to</strong> recycle <strong>to</strong> make mistakes or <strong>to</strong> give up.Finally, <strong>the</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation programme was designed <strong>to</strong> reach everyone entering<strong>the</strong> area , but only two percent bought any item that could be recycled. Thegeneral approach of public signs was thus a “hit or miss” strategy thatmissed more often than it hit.A suggested strategy:A marketing strategy would lead <strong>to</strong> quite a different solution. First, a cleargoal would be set: 90 percent of recyclable cups would be placed in arecycling container.Second, a target audience would be identified: all individuals purchasingrecyclable cups at <strong>the</strong> concession stand.Third, containers would be standardized and made cleaner <strong>to</strong> distinguishbetween garbage and recycling containers.17

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Fourth, signs would be replaced by a training and incentive programme <strong>for</strong>sales staff at <strong>the</strong> concession stand. They would be trained <strong>to</strong> provide a simpleverbal cue <strong>to</strong> every cus<strong>to</strong>mer buying a recyclable cup <strong>to</strong> instruct, remind, andthank people <strong>for</strong> recycling that cup. Staff could be given a small financialreward every day <strong>the</strong> recycling goal was met.ConclusionEnvironmental <strong>education</strong> must give people <strong>the</strong> cognitive <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong>judge what is environmentally sound. The knowledge that serves as<strong>the</strong> basis <strong>for</strong> environmental practices and policies changes rapidly asscience progresses. People must be educated <strong>to</strong> assess newdevelopments and integrate <strong>the</strong>m in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> broad context.At <strong>the</strong> same time, environmental social marketing must give people<strong>the</strong> behavioural experience that environmental change is not onlypossible but can be positive and beneficial <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong>day, as well as<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> future.Development agents find increasingly complex <strong>the</strong> job of helpingcommunities <strong>to</strong> decide how best <strong>to</strong> protect <strong>the</strong> environment and at <strong>the</strong>same time assure benefits now. The choice of a comprehensiveframework <strong>for</strong> behavioural change gives <strong>the</strong>se managers a moreaccurate idea of <strong>the</strong> perceptions of individuals and communitiesconcerning <strong>the</strong> alternatives proposed.Lessons learnedThe most important lesson we have learned about <strong>education</strong> is thatmost people are very smart and have excellent reasons <strong>for</strong> doing eventhose things which seem <strong>the</strong> most self-destructive <strong>to</strong> outsiders. Tohelp people protect <strong>the</strong> environment we must understand, respect andutilize <strong>the</strong>ir worldview and <strong>to</strong> offer “benefits” <strong>the</strong>y <strong>care</strong> about, reduce“barriers” <strong>the</strong>y worry about, and compete aggressively with <strong>the</strong>harmful behaviours <strong>the</strong>y now practice.Six steps <strong>to</strong> behaviour change1. Observe behaviour.Identify what people are doing, what <strong>the</strong>y like and don’t likeabout it. Who does it and who doesn’t. Don’t just askquestions. Look, count, record behaviour. Arrange <strong>for</strong> a fewpeople <strong>to</strong> do what you want <strong>the</strong> whole community <strong>to</strong> do.Watch <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>the</strong>y have and note <strong>the</strong> things <strong>the</strong>y seem<strong>to</strong> like.18

Social marketing2. Listen <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> people you hope will change.Ask what matters <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>m,talk about how your targetbehaviour fits in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir overall life. Get <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> talk aboutincidents, episodes, events that made a difference <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>m.Look <strong>for</strong> what <strong>the</strong>y want <strong>to</strong> get out of <strong>the</strong> behaviour and whomatters <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>m.3. Decide what you think matters.Compare people who do what you want with those whodon’t. Look <strong>for</strong> changing trends over time. Describe who youwant <strong>to</strong> change as though <strong>the</strong>y were a character in a novel youwanted readers <strong>to</strong> know. What are <strong>the</strong>y like, where do <strong>the</strong>ylive, how do <strong>the</strong>y act out <strong>the</strong> behaviour you <strong>care</strong> about? Bythis time, you should realize that you have several audiences -different segments <strong>to</strong> be reached in different ways.4. Can your thinking be generalized?Take <strong>the</strong> points you have decided are critical; such as <strong>the</strong>benefits you think <strong>the</strong>y <strong>care</strong> about, <strong>the</strong> kinds of messages andwords you think will work, and <strong>the</strong> kinds of spokesperson andchannels you think <strong>the</strong>y believe in. Test your assumptionswith a representative survey.5. Deliver benefits people want.Deliver benefits, not in<strong>for</strong>mation. Solve barriers people face,don’t just “educate” <strong>the</strong>m. This means that service deliveryand communication have <strong>to</strong> be planned <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r, with onecomplementing <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. Service delivery provides <strong>the</strong>benefits, but communication helps people believe benefits arereal and credible. Persuade as well as in<strong>for</strong>m. Make peoplefeel good about change. Touch <strong>the</strong>ir lives with hope anddon’t s<strong>care</strong> <strong>the</strong>m in<strong>to</strong> denial.6. Moni<strong>to</strong>r effects.You will make mistakes. To find and fix <strong>the</strong>m, you need <strong>to</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>r what’s going on. Don’t just evaluate your programmewhen it’s all over. Selectively moni<strong>to</strong>r those things youexpect <strong>to</strong> make a difference as <strong>the</strong> programme progresses.Moni<strong>to</strong>r by looking <strong>for</strong> indica<strong>to</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> behaviours youexpect <strong>to</strong> change.Fur<strong>the</strong>r ReadingBandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A SocialCognitive Theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.Bandura, A. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying <strong>the</strong>ory of behavioralchange. In Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.19

<strong>Planning</strong> <strong>education</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>earth</strong>Becker, G. S. 1976. The Economic Approach <strong>to</strong> Human Behavior.Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.Fishbein, M. and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior:An Introduction <strong>to</strong> Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.Fishbein, M. and S.E. Middlestadt. 1989. Using <strong>the</strong> Theory of ReasonedAction as a framework <strong>for</strong> understanding and changing AIDS-relatedbehaviors. In V.M. Mays, G.W. Albee, and S.F. Schneider (Ed.), PrimaryPrevention of AIDS, (pp.93-1 10). London. Sage Publications, Inc.Green, Lawrence W., Marshall W. Krauter, Sigrid G. Deeds and Kay B.Partridge. 1980. In Health Education <strong>Planning</strong>: A Diagnostic Approach.Mayfield Publishing Company.Kirscht, J. 1988. The health belief model and predictions of health actions.In D. Gochman (Ed.), Health Behavior: Emerging Research Perspectives,(pp. 27-41). New York. Plenum.Kotler, P. and A. R. Andreasen. 1991. Strategic Marketing <strong>for</strong> Non-profitOrganizations, Fourth Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Prentice Hall.Kotler, P. and E.L. Rober<strong>to</strong>. 1989. Social Marketing: Strategies <strong>for</strong> ChangingPublic Behavior. New York: The Free Press.Manor, R.K. 1985. Social Marketing: New Imperative <strong>for</strong> Public Health.New York. Praeger.Prochaska, J., & DiClemente, C. 1983. Self change process, self-efficacy anddecisional balance across five stages of smoking cessation. In A. R. Liss,Advances in Cancer Control: Epidemiology and Research. New York.Rosens<strong>to</strong>ck, I. M., V.J. Strecher, and M. H. Becker. 1988. Social LearningTheory and <strong>the</strong> Health Belief Model. Health Education Quarterly, Vol.15(2): 175-183. Summer.Rosens<strong>to</strong>ck, I. M. 1974. His<strong>to</strong>rical origins of <strong>the</strong> health belief model. InHealth Education Monographs, 2:328-335.Smith, W. A. 1991. Organizing Large-Scale Interventions <strong>for</strong> SexuallyTransmitted Disease Prevention. In J. N. Wasserheit, S. O. Aral, K. K.Holmes and P. J. Hitchcock, Research Issues in Human Behavior andSexually Transmitted Diseases in <strong>the</strong> AIDS Era, (pp. 219-242). Washing<strong>to</strong>n,DC. American Society <strong>for</strong> Microbiology.Solomon, D. S. 1989. A Social Marketing Perspective on CommunicationCampaigns. In Rice, R.E. and Atkin, C.K.(Ed.) Public CommunicationCampaign, pp 87-104. Sage Publications. Newbury, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.Figure 5:20