Sanitation 21 planning framework - IWA

Sanitation 21 planning framework - IWA

Sanitation 21 planning framework - IWA

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

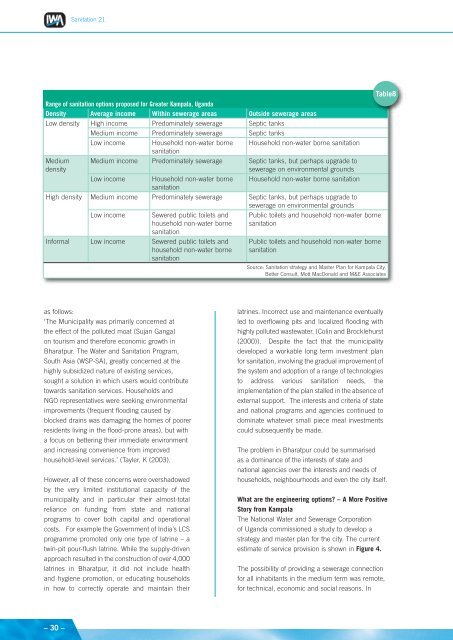

<strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>21</strong>Range of sanitation options proposed for Greater Kampala, UgandaDensity Average income Within sewerage areas Outside sewerage areasLow density High income Predominately sewerage Septic tanksMedium income Predominately sewerage Septic tanksLow income Household non-water bornesanitationHousehold non-water borne sanitationMediumdensityMedium income Predominately sewerage Septic tanks, but perhaps upgrade tosewerage on environmental groundsLow income Household non-water bornesanitationHousehold non-water borne sanitationHigh density Medium income Predominately sewerage Septic tanks, but perhaps upgrade tosewerage on environmental groundsLow income Sewered public toilets andhousehold non-water bornesanitationInformal Low income Sewered public toilets andhousehold non-water bornesanitationPublic toilets and household non-water bornesanitationPublic toilets and household non-water bornesanitationTable8Source: <strong>Sanitation</strong> strategy and Master Plan for Kampala City.Better Consult, Mott MacDonald and M&E Associatesas follows:‘The Municipality was primarily concerned atthe effect of the polluted moat (Sujan Ganga)on tourism and therefore economic growth inBharatpur. The Water and <strong>Sanitation</strong> Program,South Asia (WSP-SA), greatly concerned at thehighly subsidized nature of existing services,sought a solution in which users would contributetowards sanitation services. Households andNGO representatives were seeking environmentalimprovements (frequent flooding caused byblocked drains was damaging the homes of poorerresidents living in the flood-prone areas), but witha focus on bettering their immediate environmentand increasing convenience from improvedhousehold-level services.’ (Tayler, K (2003).However, all of these concerns were overshadowedby the very limited institutional capacity of themunicipality and in particular their almost-totalreliance on funding from state and nationalprograms to cover both capital and operationalcosts. For example the Government of India’s LCSprogramme promoted only one type of latrine – atwin-pit pour-flush latrine. While the supply-drivenapproach resulted in the construction of over 4,000latrines in Bharatpur, it did not include healthand hygiene promotion, or educating householdsin how to correctly operate and maintain theirlatrines. Incorrect use and maintenance eventuallyled to overflowing pits and localized flooding withhighly polluted wastewater. (Colin and Brocklehurst(2000)). Despite the fact that the municipalitydeveloped a workable long term investment planfor sanitation, involving the gradual improvement ofthe system and adoption of a range of technologiesto address various sanitation needs, theimplementation of the plan stalled in the absence ofexternal support. The interests and criteria of stateand national programs and agencies continued todominate whatever small piece meal investmentscould subsequently be made.The problem in Bharatpur could be summarisedas a dominance of the interests of state andnational agencies over the interests and needs ofhouseholds, neighbourhoods and even the city itself.What are the engineering options? – A More PositiveStory from KampalaThe National Water and Sewerage Corporationof Uganda commissioned a study to develop astrategy and master plan for the city. The currentestimate of service provision is shown in Figure 4.The possibility of providing a sewerage connectionfor all inhabitants in the medium term was remote,for technical, economic and social reasons. In– 30 –