Impact of different cooking methods on food quality: Retention of ...

Impact of different cooking methods on food quality: Retention of ...

Impact of different cooking methods on food quality: Retention of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

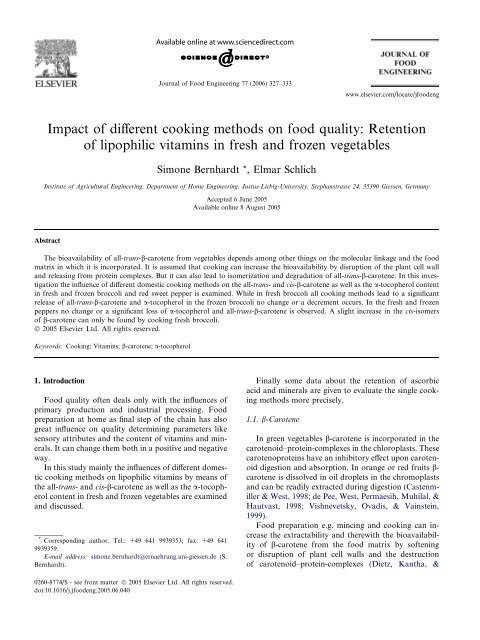

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>quality</strong>: Retenti<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> lipophilic vitamins in fresh and frozen vegetables<br />

Sim<strong>on</strong>e Bernhardt *, Elmar Schlich<br />

Institute <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Agricultural Engineering, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Home Engineering, Justus-Liebig-University, Stephanstrasse 24, 35390 Giessen, Germany<br />

Abstract<br />

Accepted 6 June 2005<br />

Available <strong>on</strong>line 8 August 2005<br />

The bioavailability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-b-carotene from vegetables depends am<strong>on</strong>g other things <strong>on</strong> the molecular linkage and the <strong>food</strong><br />

matrix in which it is incorporated. It is assumed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> can increase the bioavailability by disrupti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the plant cell wall<br />

and releasing from protein complexes. But it can also lead to isomerizati<strong>on</strong> and degradati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-b-carotene. In this investigati<strong>on</strong><br />

the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> domestic <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the all-trans- and cis-b-carotene as well as the a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tent<br />

in fresh and frozen broccoli and red sweet pepper is examined. While in fresh broccoli all <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> lead to a significant<br />

release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-b-carotene and a-tocopherol in the frozen broccoli no change or a decrement occurs. In the fresh and frozen<br />

peppers no change or a significant loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a-tocopherol and all-trans-b-carotene is observed. A slight increase in the cis-isomers<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene can <strong>on</strong>ly be found by <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> fresh broccoli.<br />

Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.<br />

Keywords: Cooking; Vitamins; b-carotene; a-tocopherol<br />

1. Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333<br />

Food <strong>quality</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten deals <strong>on</strong>ly with the influences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

primary producti<strong>on</strong> and industrial processing. Food<br />

preparati<strong>on</strong> at home as final step <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the chain has also<br />

great influence <strong>on</strong> <strong>quality</strong> determining parameters like<br />

sensory attributes and the c<strong>on</strong>tent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamins and minerals.<br />

It can change them both in a positive and negative<br />

way.<br />

In this study mainly the influences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> domestic<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> lipophilic vitamins by means <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the all-trans- andcis-b-carotene as well as the a-tocopherol<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent in fresh and frozen vegetables are examined<br />

and discussed.<br />

*<br />

Corresp<strong>on</strong>ding author. Tel.: +49 641 9939353; fax: +49 641<br />

9939359.<br />

E-mail address: sim<strong>on</strong>e.bernhardt@ernaehrung.uni-giessen.de (S.<br />

Bernhardt).<br />

0260-8774/$ - see fr<strong>on</strong>t matter Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.j<strong>food</strong>eng.2005.06.040<br />

Finally some data about the retenti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ascorbic<br />

acid and minerals are given to evaluate the single <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> more precisely.<br />

1.1. b-Carotene<br />

www.elsevier.com/locate/j<strong>food</strong>eng<br />

In green vegetables b-carotene is incorporated in the<br />

carotenoid–protein-complexes in the chloroplasts. These<br />

carotenoproteins have an inhibitory effect up<strong>on</strong> carotenoid<br />

digesti<strong>on</strong> and absorpti<strong>on</strong>. In orange or red fruits bcarotene<br />

is dissolved in oil droplets in the chromoplasts<br />

and can be readily extracted during digesti<strong>on</strong> (Castenmiller<br />

& West, 1998; de Pee, West, Permaesih, Muhilal, &<br />

Hautvast, 1998; Vishnevetsky, Ovadis, & Vainstein,<br />

1999).<br />

Food preparati<strong>on</strong> e.g. mincing and <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> can increase<br />

the extractability and therewith the bioavailability<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene from the <strong>food</strong> matrix by s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tening<br />

or disrupti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant cell walls and the destructi<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoid–protein-complexes (Dietz, Kantha, &

328 S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333<br />

Erdman, 1988; Erdman, Poor, & Dietz, 1988; van het<br />

H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> et al., 2000; Howard, W<strong>on</strong>g, Perry, & Klein, 1999).<br />

But <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> can also lead to an isomerizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

natural mainly in the all-trans-form occurring b-carotene<br />

to its cis-isomers. Cis-isomers are less bioavailable<br />

and the provitamin A-activity is lower (Deming, Teixeira,<br />

& Erdman, 2002; Deming, Baker, & Erdman,<br />

2002; Zechmeister, 1949).<br />

Oxidati<strong>on</strong> promoted by the presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> light, heat<br />

and oyxgen is the main reas<strong>on</strong> for destructi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoids<br />

(v<strong>on</strong> Elbe & Schwartz, 1996; Rodriguez-Amaya,<br />

1997).<br />

1.2. a-Tocopherol<br />

a-Tocopherol is the most important natural occurring<br />

compound with vitamin E activity (Esterbauer &<br />

Hayn, 1997). In the leaves <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> higher plants vitamin E occurs<br />

mainly as a-tocopherol which is situated inside<br />

chloroplasts. Its c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> is higher in dark than<br />

in light green leaves (Booth, 1963; Bramley et al., 2000).<br />

In pepper the a-tocopherol synthesis occurs in the<br />

chromoplasts (Arango & Heise, 1998). During fruit ripening<br />

colour changes from green to red and the chloroplasts<br />

are c<strong>on</strong>verted to chromoplasts. At the same time<br />

the synthesis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a-tocopherol rises (Lichtenthaler, 1969).<br />

Only a few studies about the change <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamin E<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent by <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetables exist. Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> them are<br />

antiquated and the authors mistrust their own results<br />

(Brubacher, 1966).<br />

1.3. Ascorbic acid<br />

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most sensitive<br />

vitamins. For this reas<strong>on</strong> it is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten used to evaluate<br />

the influences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>food</strong> processing <strong>on</strong> vitamin c<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

(Bognár, 1989).<br />

Cooking losses depend up<strong>on</strong> degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> heating, leaching<br />

into the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> medium, surface area exposed to<br />

water and oxygen, pH and other factors (Eitenmiller &<br />

Landen, 1999).<br />

1.4. Minerals<br />

Different from vitamins minerals are not destroyed by<br />

light, heat and oxygen but <strong>on</strong>ly removed from the <strong>food</strong><br />

by leaching or physical separati<strong>on</strong> (Miller, 1996).<br />

2. Materials and <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

2.1. Vegetables<br />

A green vegetable (broccoli) and a red vegetable fruit<br />

(sweet pepper) were chosen to examine if differences in<br />

localisati<strong>on</strong> and binding form <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene and a-<br />

tocopherol in the plant tissue have an effect <strong>on</strong> their<br />

behaviour during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Further differences between<br />

fresh and frozen vegetables should be examined.<br />

The vegetables were bought as <strong>on</strong>e batch at a wholesaler<br />

in order to avoid variati<strong>on</strong>s in vitamin c<strong>on</strong>tent because<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> locati<strong>on</strong>s, seas<strong>on</strong>al or climatic<br />

influences. The fresh broccoli was grown in Germany,<br />

the fresh red pepper originated from the Netherlands.<br />

The frozen vegetables were from Portugal and Spain.<br />

2.2. Cooking <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

The fresh vegetables were boiled and stewed in a<br />

stainless steel pot <strong>on</strong> a hot plate. For steaming and pressure<br />

steaming a special steam oven (Imperial Ò DLG<br />

5664) respectively pressure steam oven (Imperial Ò DG<br />

4664) was used. Temperature was about 100 ° C in the<br />

steam oven and 120 °C in the pressure steam oven.<br />

The frozen vegetables were boiled in a stainless steel<br />

pot, prepared in a steam oven (Imperial Ò DLG 5664)<br />

and in a Miele Ò Microwave (M 625 EG).<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> the fresh vegetables were cleaned,<br />

washed and cut into pieces. After removing the main<br />

part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the stem the broccoli was cut into flowerets with<br />

a weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 30 g. The red pepper was divided into quarters<br />

and cut into horiz<strong>on</strong>tal stripes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 cm.<br />

The frozen vegetables were ready to use. Broccoli was<br />

already cut into flowerets and red pepper into stripes.<br />

For each <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> procedure 300 g <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetables were<br />

weighed out. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> parameters are shown in<br />

Table 1. These parameters were evaluated with the help<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sensorial tests. All vegetables should be well-d<strong>on</strong>e but<br />

firm to the bite.<br />

For boiling the vegetables were covered completely<br />

with cold water. For stewing <strong>on</strong>ly a small amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

water (about 50–100 g) was added to avoid scorching.<br />

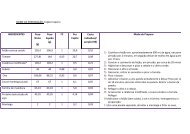

Table 1<br />

Cooking parameters (Loh, 2004)<br />

Cooking method Type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetable Heating up<br />

time (min)<br />

Cooking<br />

time (min)<br />

Boiling Broccoli, fresh 9.5 16.0<br />

Red pepper, fresh 6.3 6.0<br />

Broccoli, frozen 12.0 2.0<br />

Red pepper, frozen 9.5 5.0<br />

Stewing Broccoli, fresh 4.0 8.0<br />

Red pepper, fresh 4.0 6.0<br />

Steaming Broccoli, fresh 10.0<br />

Red pepper, fresh 10.0<br />

Broccoli, frozen 6.0<br />

Red pepper, frozen 8.0<br />

Pressure steaming Broccoli, fresh 2.0<br />

Red pepper, fresh 1.0<br />

Microwave Broccoli, frozen 4.0 4.0<br />

Red pepper, frozen 4.0 3.0

The temperature was c<strong>on</strong>trolled with the help <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a temperature<br />

sensor which was placed into the pot through a drill<br />

hole in the lid. Heating up was carried out <strong>on</strong> a high energy<br />

level until a temperature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 98 °C was reached. After<br />

this energy was reduced to the lowest level and the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

process was c<strong>on</strong>tinued until the vegetables are d<strong>on</strong>e.<br />

For the steam ovens it is <strong>on</strong>ly necessary to select the<br />

desired <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> time and to start the program. Steam is<br />

created outside the <strong>food</strong> chamber. When it has reached<br />

the required temperature it is injected into the chamber.<br />

In the microwave no additi<strong>on</strong>al water was used.<br />

Heating up occurred with a power <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 850 W then it<br />

was reduced to 450 W.<br />

All <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> are repeated five times.<br />

After <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> the vegetables were vacuum sealed.<br />

Weight was determined again to calculate mass changes<br />

during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Afterwards the samples were cooled in<br />

ice water and stored at 29 °C for two days maximum<br />

before they were sent together with dry ice by express<br />

delivery to the laboratory for vitamin analysis.<br />

2.3. Vitamin and mineral analysis<br />

Analysis was d<strong>on</strong>e by an external laboratory which is<br />

accredited after DIN EN ISO/IEC 17025. The following<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> are used:<br />

S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333 329<br />

b-Carotene: DIN EN 12823-2 2000-07: Determinati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamin A by high performance liquid chromatography—Part<br />

2: Determinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene<br />

(DIN EN 12823-2, 2000).<br />

a-Tocopherol: VDLUFA Methodenbuch Band III,<br />

13.5.4 Determinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamin E, HPLC-method<br />

(VDLUFA, 1993).<br />

Ascorbic acid: Hausmethode Lufa-Kiel (IZ-Lufa-<br />

ITL, 1999).<br />

Minerals: The mineral c<strong>on</strong>tent was determined by<br />

measuring the ash c<strong>on</strong>tent like it was d<strong>on</strong>e in other<br />

studies before (e.g. Herrmann, 1994). Ash c<strong>on</strong>tent<br />

was measured by the method <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> VDLUFA (1976).<br />

To calculate the true retenti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamins and minerals<br />

the weight changes during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> have taken into<br />

account. As aforementi<strong>on</strong>ed changes in weight were<br />

determined and the retenti<strong>on</strong> was calculated <strong>on</strong> original<br />

fresh weight basis.<br />

2.4. Statistics<br />

All <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> procedures were repeated five times. Results<br />

are given as arithmetic mean ± SD (standard deviati<strong>on</strong>).<br />

Comparis<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> means are performed using the<br />

Lord-test with an error probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1% (Kesel, Junge,<br />

& Nachtigall, 1999).<br />

3. Results and discussi<strong>on</strong><br />

Tables 2–5 show the b-carotene (all-trans- and cis-isomers)<br />

and a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tents in raw and cooked<br />

vegetables:<br />

Table 2<br />

b-Carotene and a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tents (mg/100 g) in fresh broccoli ðx SDÞ (Loh, 2004)<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boiling Stewing Steaming Pressure steaming<br />

All-trans-b-carotene 0.05 ± 0.01 0.27 ± 0.04 0.23 ± 0.03 0.21 ± 0.03 0.26 ± 0.03<br />

Cis-b-carotene 0.02 ± 0.004 0.10 ± 0.012 0.08 ± 0.009 0.07 ± 0.015 0.09 ± 0.015<br />

a-tocopherol 0.32 ± 0.05 1.54 ± 0.16 1.61 ± 0.07 1.58 ± 0.16 1.70 ± 0.08<br />

Table 3<br />

b-Carotene and a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tents (mg/100 g) in fresh red pepper ðx SDÞ (Loh, 2004)<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boiling Stewing Steaming Pressure steaming<br />

All-trans-b-carotene 0.58 ± 0.07 0.38 ± 0.12 0.35 ± 0.07 0.37 ± 0.11 0.36 ± 0.05<br />

Cis-b-carotene 0.16 ± 0.03 0.19 ± 0.03 0.16 ± 0.04 0.15 ± 0.04 0.14 ± 0.02<br />

a-tocopherol 3.93 ± 0.47 3.59 ± 0.30 3.45 ± 0.07 3.39 ± 0.24 3.70 ± 0.37<br />

Table 4<br />

b-Carotene and a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tents (mg/100 g) in frozen broccoli ðx SDÞ (Loh, 2004)<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boiling Steaming Microwave<br />

All-trans-b-carotene 0.37 ± 0.02 0.32 ± 0.02 0.30 ± 0.04 0.28 ± 0.03<br />

Cis-b-carotene 0.09 ± 0.01 0.08 ± 0.02 0.07 ± 0.01 0.07 ± 0.01<br />

a-tocopherol 1.26 ± 0.11 1.20 ± 0.06 1.43 ± 0.08 1.36 ± 0.07

330 S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333<br />

Table 5<br />

b-Carotene and a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tents (mg/100 g) in frozen red pepper ðx SDÞ (Loh, 2004)<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boiling Steaming Microwave<br />

All-trans-b-carotene 0.90 ± 0.06 0.68 ± 0.04 0.78 ± 0.10 0.72 ± 0.09<br />

Cis-b-carotene 0.18 ± 0.04 0.27 ± 0.03 0.28 ± 0.05 0.17 ± 0.02<br />

a-tocopherol 4.48 ± 0.11 4.62 ± 0.06 4.29 ± 0.31 4.65 ± 0.17<br />

3.1. b-Carotene<br />

All <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> lead to a significant release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

all-trans-b-carotene and its cis-isomers in fresh broccoli.<br />

Similar results have already been reported by Hart and<br />

Lessin in cooked broccoli and by Howard in microwaved<br />

broccoli (Hart & Scott, 1995; Howard et al., 1999;<br />

Lessin, Catigani, & Schwartz, 1997). Previous own investigati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

have already shown a release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene in<br />

fresh broccoli prepared with <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

(Schlich, Boeker, Dietrich, Loh, & Ziems, 2001).<br />

In broccoli b-carotene is incorporated in the carotenoid–protein-complexes<br />

in the chloroplasts. These socalled<br />

carotenoproteins have an inhibitory effect <strong>on</strong><br />

extractability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene from the vegetable matrix.<br />

Cooking leads to a s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tening <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the plant tissue and<br />

the denaturati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> proteins so that the carotenoids<br />

can be extracted a lot easier (Rodriguez-Amaya, 1997).<br />

It is assumed that an increased extractability may be<br />

associated with improved bioavailability (Erdmann<br />

et al., 1988).<br />

In frozen broccoli all <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> led to significant<br />

losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-b-carotene, which range between<br />

14% and 25%. Broccoli was blanched before freezing.<br />

The blanching step leads already to a disrupti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

cell membrane and a s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tening <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the vegetable matrix<br />

(Herrmann, 1996). This causes already a better extractability<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene so that higher c<strong>on</strong>tents can be<br />

proved (Oruña-C<strong>on</strong>cha, G<strong>on</strong>zález-Castro, Lopéz-<br />

Hernández, & Simal-Lozano, 1997). In the following<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> process no further release seems to be possible.<br />

In fresh red pepper stewing, steaming and pressure<br />

steaming lead to significant losses in all-trans-b-carotene<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent. By viewing the average means it seems that also<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> leads to losses. A change in the cis-b-carotene<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent cannot be proven. In frozen red pepper boiling<br />

and microwave <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> lead to significant losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

all-trans-b-carotene. Only boiling leads to a significant<br />

increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the cis-isomers.<br />

In summary it is shown that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> has rather a negative<br />

effect <strong>on</strong> the b-carotene c<strong>on</strong>tent in fresh and frozen<br />

red pepper. The red pepper is a vegetable fruit, from<br />

botanical view it is a berry (Franke, 1997). In orange<br />

or red fruits b-carotene is dissolved in oil droplets in<br />

chromoplasts and can be better extracted than from<br />

green vegetables (Castenmiller & West, 1998; de Pee<br />

et al., 1998; Vishnevetsky et al., 1999). On the other<br />

hand it seems that in this form b-carotene is much more<br />

vulnerable against oxidati<strong>on</strong> which is the main reas<strong>on</strong><br />

for the destructi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoids (Rodriguez-Amaya,<br />

1997).<br />

To estimate better the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the alltrans-<br />

andcis-b-carotene c<strong>on</strong>tents the cis-/all-trans-ratio<br />

is calculated (Loh & Schlich, 2003). Therefore the c<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cis- and all-trans-b-carotene are set proporti<strong>on</strong>ally<br />

to each other into relati<strong>on</strong>ship (Table 6). In this way<br />

it is easier to recognise if and how the ratio from cis-bcarotene<br />

to all-trans-b-carotene changes after <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

For visualisati<strong>on</strong> the arithmetic means are illustrated<br />

in Fig. 1.<br />

It strikes that by <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> fresh broccoli the ratio does<br />

not change respectively declines although you can observe<br />

a significant increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the all-trans and the cisforms.<br />

This increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the cis-isomers could probably<br />

be caused by the release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the natural in small amounts<br />

existing cis-forms and not by c<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-bcarotene.<br />

Cooking <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> frozen broccoli does not lead to significant<br />

changes. The loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all-trans-b-carotene by <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

fresh and frozen red pepper is nearly always<br />

combined with a significant increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ratio.<br />

This could be a further hint that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fresh<br />

broccoli has positive effects because all-trans-b-carotene<br />

is released and the cis-/all-trans-ratio decreases. Whereas<br />

Table 6<br />

Cis-/all-trans-ratio (in %) in the vegetables ðx SDÞ (Loh, 2004)<br />

Before <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boiling Stewing Steaming Pressure steaming Microwave<br />

Broccoli, fresh 42.0 ± 17.6 36.7 ± 6.9 33.6 ± 3.4 33.3 ± 4.3 32.2 ± 3.6 n.d.<br />

Pepper, fresh 27.9 ± 3.47 54.9 ± 19.89 47.0 ± 5.52 42.1 ± 6.21 40.0 ± 1.66 n.d.<br />

Broccoli, frozen 24.6 ± 3.6 25.0 ± 4.4 n.d. 24.5 ± 3.3 n.d. 23.3 ± 4.1<br />

Pepper, frozen 20.3 ± 3.6 39.5 ± 3.4 n.d. 36.1 ± 3.2 n.d. 23.3 ± 2.0

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> red pepper leads to a degradati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the alltrans-b-carotene<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent and an increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ratio.<br />

3.2. a-Tocopherol<br />

mg/100g<br />

All <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> lead to a significant release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

a-tocopherol in fresh broccoli. Whereas in frozen<br />

broccoli no significant changes occur. Previous own<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>s have shown the same results with the<br />

excepti<strong>on</strong> that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> frozen broccoli leads to a<br />

small release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a-tocopherol (Schlich et al., 2001).<br />

Further literature is scarce. Some authors report<br />

about losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3.7% by boiling <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetables oth-<br />

mg/100g<br />

g/100g<br />

60.0<br />

50.0<br />

40.0<br />

30.0<br />

20.0<br />

10.0<br />

0.0<br />

180<br />

160<br />

140<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333 331<br />

0<br />

Before<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Before<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ascorbic acid<br />

Boiling Steaming Microwave Pressure<br />

Steaming<br />

ers have found increases <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 18% by pressure steaming<br />

(Booth & Bradford, 1963; Brubacher, 1966).<br />

Cooking fresh red pepper does not lead to a significant<br />

change in a-tocopherol c<strong>on</strong>tent. In c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the arithmetic means it seems that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> rather<br />

causes a decrease. Cooking frozen red pepper also shows<br />

no significant changes.<br />

3.3. Ascorbic acid and mineral c<strong>on</strong>tent<br />

The influences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the single <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the<br />

ascorbic acid and mineral c<strong>on</strong>tent is exemplified in Figs.<br />

2 and 3 for fresh and frozen pepper. The results show<br />

pepper, fresh<br />

pepper, frozen<br />

Stewing<br />

Fig. 2. Ascorbic acid c<strong>on</strong>tent (arithmetic mean and standard deviati<strong>on</strong>).<br />

Before<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

cis-/all-trans-ratio<br />

Boiling Stewing Steaming Pressure<br />

Steaming<br />

Microwave<br />

Fig. 1. Cis-/all-trans-ratio (arithmetic mean).<br />

Minerals<br />

Boiling Steaming Microwave Pressure<br />

Steaming<br />

pepper, fresh<br />

pepper, frozen<br />

Stewing<br />

Fig. 3. Mineral c<strong>on</strong>tent (arithmetic mean and standard deviati<strong>on</strong>).<br />

broccoli,<br />

fresh<br />

pepper,<br />

fresh<br />

broccoli,<br />

frozen<br />

pepper,<br />

frozen

332 S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333<br />

clear that boiling leads to high losses while stewing,<br />

steaming, microwave <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> and even pressure steaming<br />

cause <strong>on</strong>ly small losses (Loh, 2004). Losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> minerals<br />

during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> are not caused by destructi<strong>on</strong> but<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly by leaching into the <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> water (Miller, 1996).<br />

Leaching is also the main reas<strong>on</strong> for the high losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

ascorbic acid during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Different studies have<br />

found an decrease <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ascorbic acid by boiling up to<br />

75% (Gould & Golledge, 1989; Petersen, 1993; Schnepf<br />

& Driskell, 1994).<br />

4. C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

By comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene and atocopherol<br />

it seems that similarities in localisati<strong>on</strong> lead<br />

to a similar behaviour during <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Cooking a green fresh vegetable promotes the release<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> lipophilic vitamins. Whereas in a red vegetable fruit<br />

respectively in the frozen vegetables which have passed<br />

a blanching step a decrease or no change occurs.<br />

For b-carotene it is known since l<strong>on</strong>ger that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

can increase the extractability and thereby probably improves<br />

the bioavailability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> b-carotene from the vegetable<br />

matrix.<br />

Whereas for a-tocopherol it is still unclear how the<br />

<strong>food</strong> matrix influences absorpti<strong>on</strong> and bioavailability.<br />

The given results let assume that <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> leads also to<br />

a better availability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a-tocopherol from sources which<br />

are difficult to access.<br />

Between the single <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g> no significant<br />

differences can be observed if <strong>on</strong>ly the results for the<br />

lipophilic vitamins are c<strong>on</strong>sidered. But if there is also<br />

paid attenti<strong>on</strong> in preserving hydrophilic compounds like<br />

ascorbic acid and minerals boiling should be avoided in<br />

favour <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> method with less water.<br />

References<br />

Arango, Y., & Heise, K. P. (1998). Localizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a-tocopherol<br />

synthesis in chromoplast envelope membranes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Capsicum annuum.<br />

I. Fruits. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Experimental Botany, 49, 1259–1262.<br />

Bognár, A. (1989). Untersuchungen über den Einfluss der Temperaturund<br />

Verpackung auf den Genuss- und Nährwert v<strong>on</strong> frischem<br />

Gemüse und Obst bei der Lagerung im Kühlschrank. Ernährungs<br />

Umschau, 36, 254–263.<br />

Booth, V. H. (1963). a-Tocopherol, its co-occurrence with chlorophyll<br />

in chloroplasts. Phytochemistry, 2, 421–427.<br />

Booth, V. H., & Bradford, M. P. (1963). The effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooking</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> atocopherol<br />

in vegetables. Internati<strong>on</strong>al Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Vitamin Research,<br />

33, 276–277.<br />

Bramley, P. M., Kafatos, A., Kelly, F. J., Manios, Y., Roxborough, H.<br />

E., Schuch, W., et al. (2000). Review vitamin E. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Science <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food and Agriculture, 80, 913–938.<br />

Brubacher, G. (1966). Über den Vitamin E-Gehalt einiger Nahrungsmittel.<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>ale Zeitschrift für Vitaminforschung, 38,<br />

409–415.<br />

Castenmiller, J. J. M., & West, C. E. (1998). Bioavailability and<br />

bioc<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoids. Annual Reviews <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 18,<br />

19–38.<br />

de Pee, S., West, C. E., Permaesih, D., Muhilal, S. M., & Hautvast, J.<br />

(1998). Orange fruit is more effective than are dark-green, leafy<br />

vegetables in increasing serum c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> retinol and bcarotene<br />

in schoolchildren in Ind<strong>on</strong>esia. American Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Clinical Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 68, 1058–1067.<br />

Deming, D. M., Baker, D. H., & Erdman, J. W. (2002). The<br />

relative vitamin A value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9-cis b-carotene is less and that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

13-cis b-carotene may be greater than the accepted 50% that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

all-trans b-carotene in gerbils. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 132,<br />

2709–2712.<br />

Deming, D. M., Teixeira, S. R., & Erdman, J. W. (2002). All-trans-bcarotene<br />

appears to be more bioavailable than 9-cis or 13-cis-bcarotene<br />

in gerbils given single oral doses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each isomer. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 132, 2700–2708.<br />

Dietz, J. M., Kantha, S. S., & Erdman, J. W. (1988). Reversed phase<br />

HPLC analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a- and b-carotene from selected raw and cooked<br />

vegetables. Plant Foods for Human Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 38, 333–341.<br />

DIN EN 12823-2, (2000). Bestimmung v<strong>on</strong> Vitamin A mit Hochleistungs-Fflüssigkeits-chromatographie.<br />

Bestimmung v<strong>on</strong> b-Carotin<br />

(Teil 2). Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Berlin: Beuth Verlag.<br />

Eitenmiller, R. R., & Landen, W. O. (1999). Vitamin analysis for the<br />

health and <strong>food</strong> sciences (pp. 223–270). Boca Rat<strong>on</strong>, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, New<br />

York, Washingt<strong>on</strong>: CRC Press.<br />

Erdman, J. W., Poor, C. L., & Dietz, J. M. (1988). Factors affecting the<br />

bioavailability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vitamin A, carotenoids, and vitamin E. Food<br />

Technology, 42, 214–221.<br />

Esterbauer, H., & Hayn, M. (1997). Vitamin E. In H. K. Biesalski<br />

(Ed.), Vitamine: physiologie, pathophysiologie, therapie (pp. 41–58).<br />

New York: Thieme Stuttgart.<br />

Franke, W. (1997). Nutzpflanzenkunde (6. neubearb. Aufl). New York:<br />

Thieme, Stuttgart.<br />

Gould, M. F., & Golledge, D. (1989). Ascorbic acid levels in<br />

c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>ally cooked versus microwave oven cooked frozen.<br />

Food Sciences and Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 42F, 145–152.<br />

Hart, D., & Scott, K. J. (1995). Development and evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an<br />

HPLC method for the analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoids in <strong>food</strong>s, and the<br />

carotenoid c<strong>on</strong>tent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetables and fruit comm<strong>on</strong>ly c<strong>on</strong>sumed in<br />

the UK. Food Chemistry, 54, 101–111.<br />

Herrmann, K. (1994). Inhaltsst<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fe der Kohlarten. Teil 1. Industrielle<br />

Obst- und Gemüseverwertung, 79, 244–252.<br />

Herrmann, K. (1996). Gemüse und Gemüseerzeugnisse. In F. Timm &<br />

K. Herrmann (Eds.), Tiefgefrorene Lebensmittel (2. Aufl., pp. 183–<br />

202). Berlin: Blackwell Wiss Verlag.<br />

Howard, L. A, W<strong>on</strong>g, A. D., Perry, A. K., & Klein, B. P. (1999). b-<br />

Carotene and ascorbic acid retenti<strong>on</strong> in fresh and processed<br />

vegetables. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Science, 64, 929–936.<br />

IZ-Lufa-ITL, (1999). Bestimmung v<strong>on</strong> Vitamin C (Ascorbinsäure).<br />

Kesel, A. B., Junge, M. M., & Nachtigall, W. (1999). Einführung in die<br />

angewandte Statistik für Biowissenschaftler. Basel, Bosten, Berlin:<br />

Birkhäuser.<br />

Lessin, W. J., Catigani, G. L., & Schwartz, S. J. (1997). Quantificati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cis–trans-isomers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> provitamin A carotenoids in fresh and<br />

processed fruits and vegetables. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Agriculture and Food<br />

Chemistry, 45, 3728–3732.<br />

Lichtenthaler, H. K. (1969). Zur Synthese der lipophilen Plastidenchin<strong>on</strong>e<br />

und Sekundärcarotinoide während der Chromoplastenentwicklung.<br />

Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft, 82,<br />

483–497.<br />

Loh, S., (2004). Bewertung des Einflusses verschiedener Garverfahren<br />

auf die sensorische und ernährungsphysiologische Qualität v<strong>on</strong><br />

frischen und TK-Gemüsen anhand ausgewählter Parameter. Cuvillier,<br />

Göttingen.<br />

Loh, S., & Schlich, E. (2003). Einfluss verschiedener Garverfahren auf<br />

die cis-/all-trans-ratio v<strong>on</strong> b-Carotin in Gemüse. Proceedings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

German Nutriti<strong>on</strong> Society, 5, 69.<br />

Miller, D. (1996). Minerals. In O. R. Fennema (Ed.), Food chemistry<br />

(3rd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker.

Oruña-C<strong>on</strong>cha, M. J., G<strong>on</strong>zález-Castro, M. J., Lopéz-Hernández, J.,<br />

& Simal-Lozano, J. (1997). Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> freezing <strong>on</strong> the pigment<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent in green beans and padrón peppers. Zeitschrift für<br />

Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und Forschung, A205, 148–152.<br />

Petersen, M. A. (1993). Influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sous vide processing, steaming and<br />

boiling <strong>on</strong> vitamin retenti<strong>on</strong> and sensory <strong>quality</strong> in broccoli<br />

flowerets. Zeitschrift für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und Forschung,<br />

197, 375–380.<br />

Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B., (1997). Carotenoids and <strong>food</strong> preparati<strong>on</strong>:<br />

The retenti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> provitamin A carotenoids in prepared, processed,<br />

and stored <strong>food</strong>. USAID. OMNI Project.<br />

Schlich, E., Boeker, M., Dietrich, J., Loh, S., & Ziems, M. (2001).<br />

Cooking parameters and vitamins. Hauswirtschaft und Wissenschaft,<br />

3, 128–132.<br />

Schnepf, M., & Driskell, J. (1994). Sensory attributes and nutrient<br />

retenti<strong>on</strong> in selected vegetables prepared by c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al and<br />

microwave <str<strong>on</strong>g>methods</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Quality, 17, 87–99.<br />

S. Bernhardt, E. Schlich / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Food Engineering 77 (2006) 327–333 333<br />

van het H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>, K. H., de Boer, B. C. J., Tijburg, L. B. M., Lucius, B.,<br />

Zijp, I., West, C. E. W., et al. (2000). Carotenoid bioavailability in<br />

humans from tomatoes processed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>different</str<strong>on</strong>g> ways determined<br />

from the carotenoid resp<strong>on</strong>se in the triglyceride-rich lipoprotein<br />

fracti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plasma after a single c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> and in plasma after<br />

four days <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong>. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, 130, 1189–1196.<br />

v<strong>on</strong> Elbe, J. H., & Schwartz, S. J. (1996). Colorants. In O. R. Fennema<br />

(Ed.), Food chemistry (3rd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker.<br />

VDLUFA, (1976). Bestimmung v<strong>on</strong> Rohasche. VDLUFA Methodenbuch<br />

Band III, 8.1. VDLUFA Verlag Darmstadt.<br />

VDLUFA, (1993). Bestimmung v<strong>on</strong> Vitamin E. VDLUFA Methodenbuch<br />

Band III, 13.5.4, VDLUFA Verlag, Darmstadt.<br />

Vishnevetsky, M., Ovadis, M., & Vainstein, A. (1999). Carotenoid<br />

sequestrati<strong>on</strong> in plants: the role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carotenoid-associated proteins.<br />

Trends in Plant Science, 4, 232–235.<br />

Zechmeister, L. (1949). Stereoisomeric provitamins A. Vitamins and<br />

Horm<strong>on</strong>es, 7, 57–81.