Near Threatened Amphibian Species - Amphibian Specialist Group

Near Threatened Amphibian Species - Amphibian Specialist Group

Near Threatened Amphibian Species - Amphibian Specialist Group

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

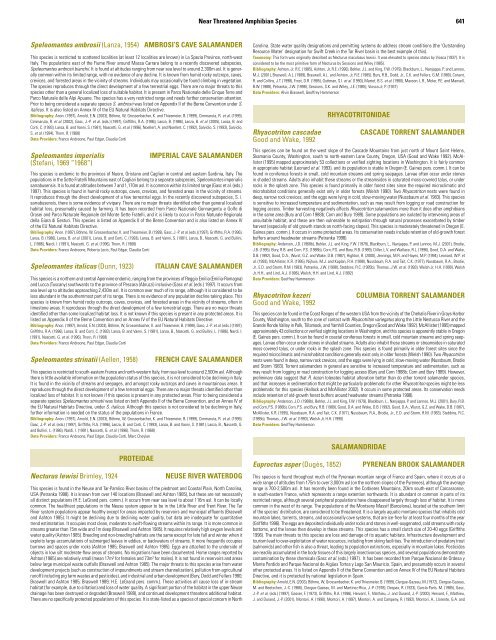

<strong>Near</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Amphibian</strong> <strong>Species</strong> 641Speleomantes ambrosii (Lanza, 1954) AMBROSI’S CAVE SALAMANDERThis species is restricted to scattered localities (at least 12 localities are known) in La Spezia Province, north-westItaly. The populations east of the Fiume River around Massa Carrara belong to a recently discovered subspecies,Speleomantes ambrosii bianchii. It is found at altitudes ranging from near sea level to around 2,300m asl. It is generallycommon within its limited range, with no evidence of any decline. It is known from humid rocky outcrops, caves,crevices, and forested areas in the vicinity of streams. Individuals may occasionally be found climbing in vegetation.The species reproduces through the direct development of a few terrestrial eggs. There are no major threats to thisspecies other than a general localized loss of suitable habitat. It is present in Parco Nazionale delle Cinque Terre andParco Naturale delle Alpi Apuane. The species has a very restricted range and needs further conservation attention.Prior to being considered a separate species S. ambrosii was listed on Appendix II of the Berne Convention under S.italicus. It is also listed on Annex IV of the EU Natural Habitats Directive.Bibliography: Anon. (1997), Arnold, E.N. (2003), Böhme, W, Grossenbacher, K. and Thiesmeier, B. (1999), Cimmaruta, R. et al. (1999),Cimmaruta, R. et al. (2002), Gasc, J.-P. et al. (eds.) (1997), Griffiths, R.A. (1996), Lanza, B. (1986), Lanza, B. et al. (2005), Lanza, B. andCorti, C. (1993), Lanza, B. and Vanni, S. (1981), Nascetti, G. et al. (1996), Noellert, A. and Noellert, C. (1992), Salvidio, S. (1993), Salvidio,S. et al. (1994), Thorn, R. (1968)Data Providers: Franco Andreone, Paul Edgar, Claudia CortiSpeleomantes imperialis(Stefani, 1969 “1968”)IMPERIAL CAVE SALAMANDERThis species is endemic to the provinces of Nuoro, Oristano and Cagliari in central and eastern Sardinia, Italy. Thepopulations in the Sette Fratelli Mountains east of Cagliari belong to a separate subspecies, Speleomantes imperialissarrabusensis. It is found at altitudes between 7 and 1,170m asl. It is common within its limited range (Gasc et al. (eds.)1997). This species is found in humid rocky outcrops, caves, crevices, and forested areas in the vicinity of streams.It reproduces through the direct development of a few terrestrial eggs. In the recently discovered subspecies, S. i.sarrabusensis, there is some evidence of vivipary. There are no major threats identified other than general localizedhabitat loss, presumably caused by farming. It has been recorded from Parco Nazionale Gennargentu e Golfo diOrosei and Parco Naturale Regionale del Monte Sette Fratelli, and it is likely to occur in Parco Naturale Regionaladella Giara di Gesturi. This species is listed on Appendix II of the Berne Convention and is also listed on Annex IVof the EU Natural Habitats Directive.Bibliography: Anon. (1997), Böhme, W, Grossenbacher, K. and Thiesmeier, B. (1999), Gasc, J.-P. et al. (eds.) (1997), Griffiths, R.A. (1996),Lanza, B. (1986), Lanza, B. et al. (2001), Lanza, B. and Corti, C. (1993), Lanza, B. and Vanni, S. (1981), Lanza, B., Nascetti, G. and Bullini,L. (1986), Nardi, I. (1991), Nascetti, G. et al. (1996), Thorn, R. (1968)Data Providers: Franco Andreone, Roberta Lecis, Paul Edgar, Claudia CortiSpeleomantes italicus (Dunn, 1923)ITALIAN CAVE SALAMANDERThis species is a northern and central Apennine endemic, ranging from the provinces of Reggio Emilia (Emilia-Romagna)and Lucca (Tuscany) southwards to the province of Pescara (Abruzzi) inclusive (Gasc et al. (eds.) 1997). It occurs fromsea level up to altitudes approaching 2,430m asl. It is common over much of its range, although it is considered to beless abundant in the southernmost part of its range. There is no evidence of any population decline taking place. Thisspecies is known from humid rocky outcrops, caves, crevices, and forested areas in the vicinity of streams, often inlimestone areas. It reproduces through the direct development of a few terrestrial eggs. There are no major threatsidentified other than some localized habitat loss. It is not known if this species is present in any protected areas. It islisted on Appendix II of the Berne Convention and on Annex IV of the EU Natural Habitats Directive.Bibliography: Anon. (1997), Arnold, E.N. (2003), Böhme, W, Grossenbacher, K. and Thiesmeier, B. (1999), Gasc, J.-P. et al. (eds.) (1997),Griffiths, R.A. (1996), Lanza, B. and Corti, C. (1993), Lanza, B. and Vanni, S. (1981), Lanza, B., Nascetti, G. and Bullini, L. (1986), Nardi, I.(1991), Nascetti, G. et al. (1996), Thorn, R. (1968)Data Providers: Franco Andreone, Paul Edgar, Claudia CortiSpeleomantes strinatii (Aellen, 1958)FRENCH CAVE SALAMANDERThis species is restricted to south-eastern France and north-western Italy, from sea level to around 2,500m asl. Althoughthere is little available information on the population status of this species, it is not considered to be declining in Italy.It is found in the vicinity of streams and seepages, and amongst rocky outcrops and caves in mountainous areas. Itreproduces through the direct development of a few terrestrial eggs. There are no major threats identified other thanlocalized loss of habitat. It is not known if this species is present in any protected areas. Prior to being considered aseparate species Speleomantes strinatii was listed on both Appendix II of the Berne Convention, and on Annex IV ofthe EU Natural Habitats Directive, under S. italicus. Although this species is not considered to be declining in Italy,further information is needed on the status of the populations in France.Bibliography: Anon. (1997), Arnold, E.N. (2003), Böhme, W, Grossenbacher, K. and Thiesmeier, B. (1999), Cimmaruta, R. et al. (1999),Gasc, J.-P. et al. (eds.) (1997), Griffiths, R.A. (1996), Lanza, B. and Corti, C. (1993), Lanza, B. and Vanni, S. (1981), Lanza, B., Nascetti, G.and Bullini, L. (1986), Nardi, I. (1991), Nascetti, G. et al. (1996), Thorn, R. (1968)Data Providers: Franco Andreone, Paul Edgar, Claudia Corti, Marc CheylanNecturus lewisi Brimley, 1924PROTEIDAENEUSE RIVER WATERDOGThis species is found in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River basins of the piedmont and Coastal Plain, North Carolina,USA (Petranka 1998). It is known from over 140 locations (Braswell and Ashton 1985), but these are not necessarilyall distinct populations (H.E. LeGrand pers. comm.). It occurs from near sea level to about 116m asl. It can be locallycommon. The healthiest populations in the Neuse system appear to be in the Little River and Trent River. The TarRiver system populations appear healthy except for areas impacted by reservoirs and municipal effluents (Braswelland Ashton 1985). It might be declining due to declining water quality, but data are inadequate for quantitativetrend estimatation. It occupies most clean, moderate to swift-flowing streams within its range. It is more common instreams greater than 15m wide and 1m deep (Braswell and Ashton 1985). It requires relatively high oxygen levels andwater quality (Ashton 1985). Breeding and non-breeding habitats are the same except for late fall and winter when itexploits large accumulations of submerged leaves in eddies, or backwaters of streams. It more frequently occupiesburrows and spaces under rocks (Ashton 1985; Braswell and Ashton 1985). Eggs are attached to the underside ofobjects in low silt moderate-flow areas of streams. No migrations have been documented. Home ranges reported byAshton (1985) are relatively small (mean 17m² for females and 73m² for males). It is not found in reservoirs and areasbelow large municipal waste outfalls (Braswell and Ashton 1985). The major threats to this species arise from waterdevelopment projects (such as construction of impoundments and stream channelization), pollution from agriculturalrunoff (including pig farm wastes and pesticides), and industrial and urban development (Bury, Dodd and Fellers 1980;Braswell and Ashton 1985; Braswell 1989; H.E. LeGrand pers. comm.). These activities all cause loss of in-streamhabitat (for example, due to siltation) and loss of water quality. A significant portion of the habitat in the upper Neusedrainage has been destroyed or degraded (Braswell 1989), and continued development threatens additional habitat.There are no specifically protected populations of this species. It is state-listed as a species of special concern in NorthCarolina. State water quality designations and permitting systems do address stream conditions (the ‘OutstandingResource Water’ designation for Swift Creek in the Tar River basin is the best example of this).Taxonomy: This form was originally described as Necturus maculosus lewisi. It was elevated to species status by Viosca (1937). It isconsidered to be the most primitive form of Necturus by Sessions and Wiley (1985).Bibliography: Ashton, Jr, R.E. (1985), Ashton, Jr, R.E. (1990), Behler, J.L. and King, F.W. (1979), Blackburn, L., Nanjappa, P. and Lannoo,M.J. (2001), Braswell, A.L. (1989), Braswell, A.L. and Ashton, Jr, R.E. (1985), Bury, R.B., Dodd, Jr., C.K. and Fellers, G.M. (1980), Conant,R. and Collins, J.T. (1998), Frost, D.R. (1985), Guttman, S.I. et al. (1990), Martof, B.S. et al. (1980), Maxson, L.R., Moler, P.E. and Mansell,B.W. (1988), Petranka, J.W. (1998), Sessions, S.K. and Wiley, J.E. (1985), Viosca Jr, P. (1937)Data Providers: Alvin Braswell, Geoffrey HammersonRhyacotriton cascadaeGood and Wake, 1992RHYACOTRITONIDAECASCADE TORRENT SALAMANDERThis species can be found on the west slope of the Cascade Mountains from just north of Mount Saint Helens,Skamania County, Washington, south to north-eastern Lane County, Oregon, USA (Good and Wake 1992). McAllister(1995) mapped approximately 53 collections or verifi ed sighting locations in Washington. It is fairly commonin appropriate habitat (Leonard et al. 1993), and its population is stable in Oregon (E. Gaines pers. comm.). It can befound in coniferous forests in small, cold mountain streams and spring seepages. Larvae often occur under stonesin shaded streams. Adults also inhabit these streams or the streamsides in saturated moss-covered talus, or underrocks in the splash zone. This species is found primarily in older forest sites since the required microclimatic andmicrohabitat conditions generally exist only in older forests (Welsh 1990). Two Rhyacotriton nests were found indeep, narrow rock crevices, and the eggs were lying in cold, slow-moving water (Nussbaum et al. 1983). This speciesis sensitive to increased temperature and sedimentation, such as may result from logging or road construction forlogging access. Timber harvesting negatively affects Rhyacotriton salamanders more than it does other amphibiansin the same area (Bury and Corn 1988b; Corn and Bury 1989). Some populations are isolated by intervening areas ofunsuitable habitat, and these are then vulnerable to extirpation through natural processes exacerbated by timberharvest (especially of old growth stands on north-facing slopes). This species is moderately threatened in Oregon (E.Gaines pers. comm.). It occurs in some protected areas. Its conservation needs include retention of old-growth forestbuffers around headwater streams (Petranka 1998).Bibliography: Anderson, J.D. (1968b), Behler, J.L. and King, F.W. (1979), Blackburn, L., Nanjappa, P. and Lannoo, M.J. (2001), Brodie,J.B. (1995), Bury, R.B. and Corn, P.S. (1988b), Corn, P.S. and Bury, R.B. (1989), Diller, L.V. and Wallace, R.L. (1996), Good, D.A. and Wake,D.B. (1992), Good, D.A., Wurst, G.Z. and Wake, D.B. (1987), Highton, R. (2000), Jennings, M.R. and Hayes, M.P. (1994), Leonard, W.P. etal. (1993), McAllister, K.R. (1995), Nijhuis, M.J. and Kaplan, R.H. (1998), Nussbaum, R.A. and Tait, C.K. (1977), Nussbaum, R.A., Brodie,Jr., E.D. and Storm, R.M. (1983), Petranka, J.W. (1998), Stebbins, R.C. (1985b), Thomas, J.W. et al. (1993), Welsh Jr, H.H. (1990), WelshJr, H.H., and Lind, A.J. (1996), Welsh, H.H. and Lind, A.J. (1992)Data Providers: Geoffrey HammersonRhyacotriton kezeriGood and Wake, 1992COLUMBIA TORRENT SALAMANDERThis species can be found in the Coast Ranges of the western USA from the vicinity of the Chehalis River in Grays HarborCounty, Washington, south to the zone of contact with Rhyacotriton variegatus along the Little Nestucca River and theGrande Ronde Valley in Polk, Tillamook, and Yamhill Counties, Oregon (Good and Wake 1992). McAllister (1995) mappedapproximately 43 collections or verified sighting locations in Washington, and this species is apparently stable in Oregon(E. Gaines pers. comm.). It can be found in coastal coniferous forests in small, cold mountain streams and spring seepages.Larvae often occur under stones in shaded streams. Adults also inhabit these streams or streamsides in saturatedmoss-covered talus, or under rocks in the splash zone. This species is found primarily in older forest sites since therequired microclimatic and microhabitat conditions generally exist only in older forests (Welsh 1990). Two Rhyacotritonnests were found in deep, narrow rock crevices, and the eggs were lying in cold, slow-moving water (Nussbaum, Brodieand Storm 1983). Torrent salamanders in general are sensitive to increased temperature and sedimentation, such asmay result from logging or road construction for logging access (Bury and Corn 1988b; Corn and Bury 1989). However,preliminary data suggest that R. kezeri tolerates habitat alteration better than do other torrent salamander species,and that increases in sedimentation that might be particularly problematic for other Rhyacotriton species might be lessproblematic for this species (Hallock and McAllister 2002). It occurs in some protected areas. Its conservation needsinclude retention of old-growth forest buffers around headwater streams (Petranka 1998).Bibliography: Anderson, J.D. (1968b), Behler, J.L. and King, F.W. (1979), Blackburn, L., Nanjappa, P. and Lannoo, M.J. (2001), Bury, R.B.and Corn, P.S. (1988b), Corn, P.S. and Bury, R.B. (1989), Good, D.A. and Wake, D.B. (1992), Good, D.A., Wurst, G.Z. and Wake, D.B. (1987),McAllister, K.R. (1995), Nussbaum, R.A. and Tait, C.K. (1977), Nussbaum, R.A., Brodie, Jr., E.D. and Storm, R.M. (1983), Stebbins, R.C.(1985b), Thomas, J.W. et al. (1993), Welsh Jr, H.H. (1990)Data Providers: Geoffrey HammersonEuproctus asper (Dugès, 1852)SALAMANDRIDAEPYRENEAN BROOK SALAMANDERThis species is found throughout much of the Pyrenean mountain range of France and Spain, where it occurs at awide range of altitudes from 175m to over 3,000m asl (on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees), although the averagerange is 700-2,500m asl. It has recently been found in the Corbieres Mountains, 20km south-east of Carcassonne,in south-eastern France, which represents a range extention northwards. It is abundant or common in parts of itsrestricted range, although several peripheral populations have disappeared largely through loss of habitat. It is morecommon in the west of its range. The populations of the Montseny Massif (Barcelona), located at the southern limitof the species’ distribution, are considered to be threatened. It is a largely aquatic montane species that inhabits coldmountain lakes, torrents, streams, and occasionally cave systems, that are ice-free for at least four months of the year(Griffiths 1996). The eggs are deposited individually under rocks and stones in well-oxygenated, cold streams with rockybottoms, and the larvae then develop in these streams. This species has a small clutch size of 20-40 eggs (Griffiths1996). The main threats to this species are loss and damage of its aquatic habitats. Infrastructure development andtourism lead to over-exploitation of water resources, including from skiing facilities. The introduction of predatory trout(salmonids) and other fish is also a threat, leading to population extinctions, especially in mountain lakes. Pesticidesare readily accumulated in the body tissues of this largely insectivorous species, and several populations demonstratecontamination by these chemicals (Gasc et al. (eds.) 1997). It has been recorded from Parque Nacional de Ordesa yMonte Perdido and Parque Nacional de Aigües Tortes y Lago San Mauricio, Spain, and presumably occurs in severalother protected areas. It is listed on Appendix II of the Berne Convention and on Annex IV of the EU Natural HabitatsDirective, and it is protected by national legislation in Spain.Bibliography: Arnold, E.N. (2003), Böhme, W, Grossenbacher, K. and Thiesmeier, B. (1999), Clergue-Gazeau, M. (1972), Clergue-Gazeau,M. and Beetschen, J.-C. (1966), Clergue-Gazeau, M. and Martinez-Rica, J.-P. (1978), Despax, R. (1923), García-París, M. (1985), Gasc,J.-P. et al. (eds.) (1997), Gasser, F. (1973), Griffiths, R.A. (1996), Hervant, F., Mathieu, J. and Durand, J.-P. (2000), Hervant, F., Mathieu,J. and Durand, J.-P. (2001), Montori, A. (1990), Montori, A. (1997), Montori, A. and Campeny, R. (1992), Montori, A., Llorente, G.A. and