Winning Hearts and Minds? - Tufts - Tufts University

Winning Hearts and Minds? - Tufts - Tufts University

Winning Hearts and Minds? - Tufts - Tufts University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

©2011 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved.Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educationalpurposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, <strong>and</strong> newsreporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text <strong>and</strong> image filesfrom this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein InternationalCenter’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material <strong>and</strong>/orreproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of theFeinstein International Center, is prohibited.Feinstein International Center<strong>Tufts</strong> <strong>University</strong>200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800Medford, MA 02155USAtel: +1 617.627.3423fax: +1 617.627.3428fic.tufts.edu2Feinstein International Center

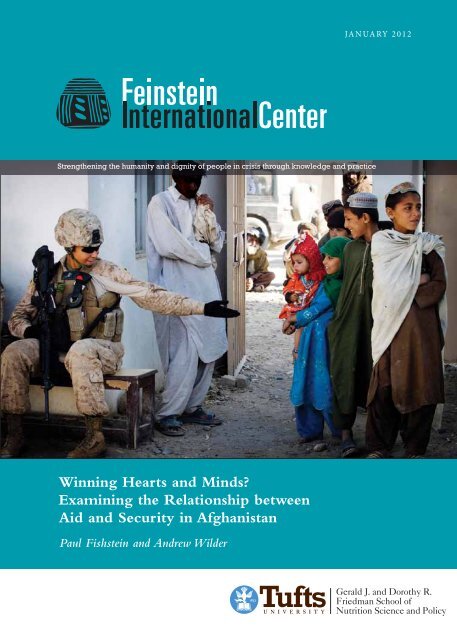

AuthorsPaul Fishstein is a visiting Fellow at the Feinstein International Center at <strong>Tufts</strong><strong>University</strong>, Medford, Massachusetts. Andrew Wilder is Director, Afghanistan <strong>and</strong>Pakistan Programs, United States Institute for Peace, Washington, District of Columbia<strong>and</strong> former Research Director at the Feinstein International Center.AcknowledgementsThe authors wish to thank the following people <strong>and</strong> institutions <strong>and</strong> acknowledge theircontribution to the research:• Research colleagues Ahmad Hakeem (“Shajay”), Sayed Yaseen Naqshpa, AhmadGul, Sayed Yaqeen, Faraidoon Shariq, <strong>and</strong> Geert Gompelman for their assistance <strong>and</strong>insights as well as companionship in the field.• Frances Brown, David Katz, David Mansfield, <strong>and</strong> Astri Suhrke for their substantivecomments <strong>and</strong> suggestions on a draft version.• William Thompson <strong>and</strong> DAI for facilitating field research in Paktia Province,AusAID staff <strong>and</strong> the UNAMA office in Tarin Kot for facilitating field research inUruzgan Province, <strong>and</strong> the ACTED office in Maimana for facilitating field researchin Faryab Province.• Robert Grant <strong>and</strong> the Wilton Park conference center for their joint sponsorship ofthe March 2010 conference on “‘<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>’ in Afghanistan:Assessing the Effectiveness of Development Aid in COIN Operations.”• Staff of the Afghanistan Research <strong>and</strong> Evaluation Unit (AREU) for support duringvisits to Afghanistan.Paul Fishstein also wishes to thank the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at theHarvard Kennedy School for the fellowship during which much of this work was done.The Balkh, Faryab, <strong>and</strong> Uruzgan analysis benefitted from historical <strong>and</strong> politicalbackground overviews produced by Mervyn Patterson <strong>and</strong> Martine van Bijlert, leadinganalysts of these provinces. The section on the evolution of security-driven aidbenefitted from the very substantive contribution of Dr. Stuart Gordon.Thanks go to Joyce Maxwell for her editorial guidance <strong>and</strong> for helping to clarifyunclear passages, <strong>and</strong> to Bridget Snow for her efficient <strong>and</strong> patient work on theproduction of the final document.Thank youGenerous funding for the research was provided by the Afghanistan Research <strong>and</strong>Evaluation Unit (AREU),the Australian Agency for International Development(AusAID), the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, <strong>and</strong> the SwedishInternational Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).Cover photoU.S. military <strong>and</strong> children at health center, Helm<strong>and</strong>Photo by © Kate Holt/Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN)

ContentsAcknowledgementsGlossary of non-English words <strong>and</strong> expressionsAcronyms <strong>and</strong> abbreviationsviiviiiExecutive Summary 21. Introduction 81.1 Purpose, rationale, <strong>and</strong> description of study 81.2 Methodology 101.3 Similar <strong>and</strong> related research in Afghanistan 112. Evolution of security-driven aid 132.1 Current approaches 153. Aid <strong>and</strong> security in Afghanistan 203.1 Provincial background 203.2 Models used for employing aid in the five provinces 214. Drivers of conflict <strong>and</strong> insecurity 294.1 Corruption, poor governance, <strong>and</strong> predatory government 294.2 Ethnic, tribal, <strong>and</strong> factional issues 314.3 Poverty <strong>and</strong> unemployment 344.4 International military forces 354.5 Religious extremism 364.6 Conflict over scarce resources 384.7 Pakistan <strong>and</strong> the other “neighbors” 384.8 Opportunities for insurgents to exploit grievances 405. Perceptions of aid projects 415.1 “Nothing, or not enough, was done” 425.2 Inequitable distribution: “They got more than we did” 425.3 Corruption 445.4 “Wrong kind” of projects 465.5 Poorly implemented (low quality) 475.6 Non-sustainable 505.7 Positive views: Some good news 51

6. The stabilizing <strong>and</strong> destabilizing effects of aid 546.1 Addressing the wrong drivers of insecurity 576.2 Subverted by insurgents 606.3 Poor quality of implementation 616.4 Destabilizing influences of aid 616.4.1 Corruption 616.4.2 Competition over resources: The war-aid economy <strong>and</strong> perverse incentives 626.4.3 Reinforcing inequalities <strong>and</strong> creating perceived winners <strong>and</strong> losers 646.4.4 Regional disparities 647. Summary of conclusions <strong>and</strong> recommendations 67Annex A: Research Methodology 72Bibliography 78v

MAPMap credit: Hans C. Ege Wenger, <strong>Tufts</strong> <strong>University</strong>vi

Glossary of non-English words <strong>and</strong> expressionsarbab/khanarbakaibakhsheeshjihadjihadikarezkomakkuchiskunjalamadrassamahroummalekmujahidinmullahshariashurasudhtak o tooktalibtanzimtashkiltekadarulamawasitawoleswalwoleswalizulmHead of community or tribeTribal security forces indigenous to the Loya Paktia region. The term has beeninformally adopted to refer to irregular local security forces.Financial gift, usually small, offered as a favor to accomplish a taskHoly war, usually referring to the 1979–92 war against the Soviet occupationComm<strong>and</strong>er or political leader who gained his strength during the jihad years(1979–92)Traditional irrigation system that taps aquifers <strong>and</strong> brings water to the surfacethrough often-lengthy underground canalsHelp, aid, or assistanceNomadsType of animal feedReligious school or training academyDeprived, left out, often with the implication of being discriminated againstLocal leaderGuerillas who fought in the 1979–92 war against the Soviet occupation (literally,those who fight jihad, or holy war)Religious leaderIslamic lawCouncilUsury, excessive interest ratesA bit of noiseIslamic student (singular of taliban)Organization or political partyApproved staffing pattern or list of sanctioned posts in a government officeContractor, one who does a piece of work for paymentSunni religious scholarsPersonal relationship or connection often used to obtain a favor such as employmentor processing of paperworkDistrict administrator or governor; i.e., one who administers a woleswaliAdministrative division within a provinceCrueltyvii

Acronyms <strong>and</strong> abbreviationsADFANAANPANSFAREUAusAIDCDCCERPCFWCIMICCOINCSODDRDFIDDODDODDEQUIPEUFATAFCOFICGAOGIRoAIDPIEDIMFISAFMODMRRDNATONGONSPODAOECDPDCPRTAustralian Defense ForceAfghan National ArmyAfghan National PoliceAfghan National Security ForcesAfghanistan Research <strong>and</strong> Evaluation UnitAustralian Agency for International DevelopmentCommunity Development CouncilComm<strong>and</strong>ers Emergency Response ProgramCash-For-WorkCivil-Military CooperationCounterinsurgencyCentral Statistics OrganizationDisarmament, Demobilization, <strong>and</strong> ReintegrationDepartment for International Development (UK)Department of Defense (U.S.)Department of Defense DirectiveEducation Quality Improvement ProgramEuropean UnionFederally Administered Tribal AreasForeign <strong>and</strong> Commonwealth Office (UK)Feinstein International CenterGovernment Accountability Office (U.S.)Government of the Islamic Republic of AfghanistanInternally displaced personImprovised explosive deviceInternational military forcesInternational Security Assistance ForceMinistry of Defense (UK)Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> DevelopmentNorth Atlantic Treaty OrganizationNon-governmental organizationNational Solidarity ProgramOfficial Development AssistanceOrganization for Economic Co-operation <strong>and</strong> DevelopmentProvincial Development CommitteeProvincial Reconstruction Teamviii

PsyOpsQDRQIPS/CRSSIDASIGARSTARTUN OCHAUNAMAUNFPAUNTAGUSDAUSGPsychological OperationsQuadrennial Defense ReviewQuick Impact ProjectOffice of the Coordinator for Reconstruction <strong>and</strong> Stabilization (U.S.)Swedish International Development Cooperation AgencySpecial Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (U.S.)Stabilisation <strong>and</strong> Reconstruction Task Force (Canada)United Nations Office of Coordinator for Humanitarian AffairsUnited Nations Assistance Mission for AfghanistanUnited Nations Population FundUnited Nations Transition Assistance GroupU.S. Department of AgricultureUnited States Governmentix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYPolitical <strong>and</strong> security objectives have alwaysinfluenced U.S. foreign assistance policies <strong>and</strong>priorities. Since 9/11, however, development aidfor countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, <strong>and</strong> Pakistanhas increasingly <strong>and</strong> explicitly been militarized<strong>and</strong> subsumed into the national security agenda.In the U.S. as well as in other western nations,the re-structuring of aid programs to reflect theprevailing foreign policy agenda of confrontingglobal terrorism has had a major impact ondevelopment strategies, priorities, <strong>and</strong> structures.The widely held assumption in military <strong>and</strong>foreign policy circles that development assistanceis an important “soft power” tool to win consentfor the presence of foreign troops in potentiallyhostile areas, <strong>and</strong> to promote stabilization <strong>and</strong>security objectives, assumes a relationshipbetween poverty <strong>and</strong> insecurity that is shared bymany in the development <strong>and</strong> humanitariancommunity.The assumption that aid projects improvesecurity has had a number of implications for theU.S. <strong>and</strong> other western donors, including: 1) asharp increase in development assistance; 2) anincreasing percentage of assistance programmedbased on strategic security considerations ratherthan on the basis of poverty <strong>and</strong> need; <strong>and</strong>, 3) amuch greater role for the military or combinedcivil-military teams in activities that weretraditionally the preserve of development <strong>and</strong>humanitarian organizations. At the same time,civilian agencies, including non-governmentalorganizations, have also been increasinglyenlisted in aid <strong>and</strong> development projects thathave explicit stabilization objectives.Given how widespread the assumption is, <strong>and</strong>given its major impact on aid <strong>and</strong>counterinsurgency policies, there is littleempirical evidence that supports the assumptionthat reconstruction assistance is an effective toolto “win hearts <strong>and</strong> minds,” <strong>and</strong> improve securityor stabilization in counterinsurgency contexts.To help address this lack of evidence, theFeinstein International Center (FIC) at <strong>Tufts</strong><strong>University</strong> conducted a comparative study inAfghanistan <strong>and</strong> the Horn of Africa to examinethe effectiveness of aid projects in promotingsecurity objectives in stabilization <strong>and</strong>counterinsurgency contexts.This paper presents a summary of the findingsfrom the Afghanistan study. Research wasconducted in five provinces, three in the south<strong>and</strong> east (Helm<strong>and</strong>, Paktia, <strong>and</strong> Uruzgan) whichwere considered insecure <strong>and</strong> two in the north(Balkh <strong>and</strong> Faryab) which were consideredrelatively secure, as well as in Kabul city.Through interviews <strong>and</strong> focus group discussionswith a range of respondents in key institutions<strong>and</strong> in communities, views were elicited on thedrivers of insecurity, characteristics of aidprojects <strong>and</strong> aid implementers (including themilitary), <strong>and</strong> effects of aid projects on thepopularity of aid actors <strong>and</strong> on security.Drivers of insecurityThe study first tried to underst<strong>and</strong> the drivers ofinsecurity in the five provinces in order to beable to assess whether aid projects wereaddressing them. The main reported drivers ofconflict or insecurity were poor governance,corruption, <strong>and</strong> predatory officials; ethnic, tribal,or factional conflict; poverty <strong>and</strong> unemployment;behavior of foreign forces (including civiliancasualties, night raids, <strong>and</strong> disrespect for Afghanculture); competition for scarce resources (e.g.,water, l<strong>and</strong>); criminality <strong>and</strong> narcotics (<strong>and</strong>counter-narcotics); ideology or religiousextremism; <strong>and</strong>, the geopolitical policies ofPakistan <strong>and</strong> other regional neighbors. Many ofthese factors are complex, intertwined, <strong>and</strong>overlapping, so it was difficult to isolate thestrength <strong>and</strong> influences of each. Respondentsgave notably different weight to the variousfactors in the different provinces. In the southern<strong>and</strong> eastern provinces, poor governance <strong>and</strong>tribal <strong>and</strong> factional conflicts were given moreweight, while in the northern provinces poverty<strong>and</strong> unemployment were given more weight. Inthe south <strong>and</strong> east, the actions of theinternational military were reported to be animportant source of insecurity, whereas in thenorth international military forces weregenerally seen as more of a source of security. Acommon theme that cut across many thematic2Feinstein International Center

<strong>and</strong> geographical areas was that of injustice,including the perceived injustice that a fewcorrupt officials <strong>and</strong> powerbrokers werebenefiting disproportionally from internationalassistance at the expense of the majority ofAfghans. Insurgents were described as adept attaking advantage of the opportunities offered bycommunities’ grievances <strong>and</strong> perceptions ofinjustice.Perceptions of aid projectsThe study looked at whether <strong>and</strong> how aidprojects addressed the drivers of insecurityidentified by respondents <strong>and</strong>/or were effective atwinning hearts <strong>and</strong> minds. The research foundthat development projects, rather than generatinggood will <strong>and</strong> positive perceptions, wereconsistently described negatively by Afghans.Responses suggested that not only were projectsnot winning people over to the government side,but perceptions of the misuse <strong>and</strong> abuse of aidresources were in many cases fueling thegrowing distrust of the government, creatingenemies, or at least generating skepticismregarding the role of the government <strong>and</strong> aidagencies. The chief complaints were that projectswere insufficient, both in terms of quantity <strong>and</strong>of quality; unevenly distributed geographically,politically, <strong>and</strong> socially; <strong>and</strong>, above all, associatedwith extensive corruption, especially those thatinvolved multiple levels of subcontracting.Communities did provide positive views on theNational Solidarity Program (NSP), somesignificant <strong>and</strong> highly visible infrastructureprojects, <strong>and</strong> long-serving aid agencies that hadestablished relationships with communities.Stabilizing <strong>and</strong> destabilizing effects of aidWhile the environments in the five provincesdiffered, a number of consistent observationsemerged concerning the effectiveness of aidprojects in promoting short- <strong>and</strong> long-termstabilization objectives. First, in some areas aidprojects seemed to have had some short-termpositive security effects at a tactical level,including reported intelligence gathering gains<strong>and</strong> some limited force protection benefits forinternational forces. In some cases aid projectsalso helped to facilitate creating relationships, inpart by providing a “platform” or context tolegitimize interaction between international <strong>and</strong>local actors who would otherwise find it difficultto meet. However, despite these limited tacticalbenefits, there was little concrete evidence in anyof the five provinces that aid projects werehaving more strategic level stabilization orsecurity benefits such as winning populationsaway from insurgents, legitimizing thegovernment, or reducing levels of violentconflict.The research actually found more evidence ofthe destabilizing rather than the stabilizingeffects of aid, especially in insecure areas wherethe pressures to spend large amounts of moneyquickly were greatest. The most destabilizingaspect of the war-aid economy was in fuelingmassive corruption that served to delegitimizethe government. Other destabilizing effectsincluded: generating competition <strong>and</strong> conflictover aid resources, often along factional, tribal orethnic lines; creating perverse incentives tomaintain an insecure environment, as was thecase with security contractors who were reportedto be “creating a problem to solve a problem”;fueling conflicts between communities overlocations of roads <strong>and</strong> the hiring of laborers; <strong>and</strong>,causing resentment by reinforcing existinginequalities <strong>and</strong> further strengthening dominantgroups, often allied with political leaders <strong>and</strong>regional strongmen, at the expense of others.The research found that while the drivers ofinsecurity <strong>and</strong> conflict in Afghanistan are varied<strong>and</strong> complex, the root causes are often politicalin nature, especially in terms of competition forpower <strong>and</strong> resources between <strong>and</strong> among ethnic,tribal, <strong>and</strong> factional groups. Internationalstabilization projects, however, tended to laymore emphasis on socio-economic rather thanpolitical drivers of conflict, <strong>and</strong> thereforeprimarily focused on addressing issues such asunemployment, illiteracy, lack of social services,<strong>and</strong> inadequate infrastructure such as roads. As aresult, aid projects were often not addressing themain sources of conflict, <strong>and</strong> in some cases fueledconflict by distributing resources that rivalgroups then fought over.<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 3

Conclusions <strong>and</strong> recommendationsThe following section highlights the mainconclusions <strong>and</strong> recommendations of this study,which are largely consistent with findings fromseveral other evaluations <strong>and</strong> studies looking atthe relationship between aid <strong>and</strong> security inAfghanistan. There is growing awareness bycivilian <strong>and</strong> military actors of some of the issuesraised here, <strong>and</strong> steps have been taken to addresssome of them. However, progress has often beenslow because many of the institutional incentivesfor why aid funds are spent in ways that can beineffective or destabilizing remain unchanged.1. Primacy of political over economicdrivers of conflictIn the more insecure areas the reasons identifiedby interviewees for insecurity <strong>and</strong> opposition tothe government were related most frequently topolitical issues such as the corrupt <strong>and</strong> predatorybehavior of government actors. Moststabilization initiatives, however, haveemphasized economic drivers of conflict –focusing on poverty, unemployment, illiteracy,delivery of social services, <strong>and</strong> building ofinfrastructure. In the less insurgency-affectedareas, where poverty <strong>and</strong> unemployment weregiven as more important drivers of conflict,well-delivered, conflict-sensitive aidinterventions may have been more effective athelping to consolidate stability than aid ininsecure areas was in reversing instability.The population-centered counterinsurgency(COIN) approach of winning the populationaway from insurgents <strong>and</strong> over to thegovernment struggled to gain traction in partbecause the government’s leadership neverseemed to share the objective of winning overthe population, <strong>and</strong> instead often pursued apatronage-based approach to buy the support oflocal strongmen. Furthermore, the U.S. <strong>and</strong>many of its NATO/ISAF (International SecurityAssistance Force) allies had contradictorystrategies of simultaneously wanting to provideservices <strong>and</strong> good government to win over thepopulation, but also supporting local strongmenwhose predatory behavior alienated the localpopulation. Aid delivered by or associated withcorrupt officials or strongmen who were in manycases responsible for alienating people in the firstplace has, not surprisingly, proven to be anineffective way of winning people over to thegovernment. Lack of progress on governance hasnot primarily been due to lack of money, but toa lack of political will or a shared strategy on thepart of the government <strong>and</strong> the internationalcommunity to push a consistent reform agenda.Recommendations:• Focus more on identifying the drivers ofconflict <strong>and</strong> alienation, <strong>and</strong> if these areprimarily political, governance, <strong>and</strong> rule-oflawrelated, do not assume they can effectivelybe addressed through primarily socioeconomicinterventions.• The international community should take abetter-coordinated <strong>and</strong> more forceful st<strong>and</strong> oncertain key issues that would help promotebetter governance (e.g., merit-basedappointments into key national <strong>and</strong> subnationalpositions, more rigorous anticorruptionmeasures including bettermonitoring of donor expenditures, avoidingalliances with notorious strongmen known forcorrupt <strong>and</strong> predatory behavior).2. Spending too much too quickly can becounterproductive – less can be morePressure to spend too much money too quickly isnot only wasteful, but undermines both security<strong>and</strong> development objectives, especially ininsecure environments with weak institutions.However, powerful career <strong>and</strong> institutionalincentives often contribute to quantity beingprioritized <strong>and</strong> rewarded over quality. Theseincentives include the strong bureaucraticimperative to grow budgets as much as possible,<strong>and</strong> to then spend as much money as quickly aspossible in order to justify further budgetgrowth; for Provincial Reconstruction Teams(PRTs), to demonstrate performance duringshort-term rotations based on the quantity offunds expended rather than on the impact thatthe funded activities have had; for manycontractors <strong>and</strong> NGOs, to generate overheadfunding for headquarters based on program4Feinstein International Center

udgets spent. The experience of the NSP <strong>and</strong>some other development projects suggests that,in terms of development, quality should not besacrificed for the sake of quantity. The researchsuggests that in terms of potential stabilizingbenefits as well as positive developmentoutcomes, the process of development, especiallyin building <strong>and</strong> sustaining relationships, despitebeing time-consuming, is as if not moreimportant than the product of development.Unfortunately, there are few incentives forspending less money more effectively over time.Discussions with individual field-level actors aswell as senior officials confirm that the problemis often not that we do not know what needs tobe done, but rather that institutional incentivesreward getting <strong>and</strong> spending money. “Less ismore” can never be a reality when “more ismore” is rewarded.Recommendations:• Provide incentives for quality <strong>and</strong> impact ofaid spending over quantity. Aid money shouldonly be committed when it can be spent in aneffective <strong>and</strong> accountable manner.• Address the “use it or lose it” problem,whereby budgets are forfeited if not spent, byallowing unused budget amounts to be rolledover into following years, establishing multiyearpredictable funding, <strong>and</strong> making moreuse of longer-term trust fund-typemechanisms that could be drawn down basedon need rather than annual budget cycles.These approaches would reduce the currentinstitutional incentives <strong>and</strong> negative effects ofspending too much too fast, while alsoconveying a sense of long-term commitmentto Afghanistan.3. Insufficient attention has been paid tothe political economy of aid inAfghanistanAn important consequence of the pressure tospend too quickly has been inadequateconsideration of incentive structures facingpolicy makers, donors, implementers, <strong>and</strong>communities. Evidence from this as well asother studies indicates that the way in which aidhas been delivered has contributed to instabilitythrough reinforcing uneven <strong>and</strong> oppressivepower relationships, favoring or being perceivedto favor one community or individual overothers, <strong>and</strong> providing a valuable resource foractors to fight over. The most destabilizingaspect of the war-aid economy in Afghanistan,however, has been its role in fueling corruption,which delegitimizes both the government <strong>and</strong>the international community. Under the currentstatus quo of weak institutions <strong>and</strong> insecurity,some powerful actors are doing very well, <strong>and</strong> sohave little incentive to push for change.Recommendations:• Invest more in underst<strong>and</strong>ing the politicaleconomy of aid, including local conflictdynamics, the impact of the war-aid economyon these dynamics, the perceived winners <strong>and</strong>losers of aid programs, <strong>and</strong> the role of theseprograms in legitimizing (or delegitimizing)the government.• Give more attention to underst<strong>and</strong>ing theincentive structures of national <strong>and</strong>international civilian <strong>and</strong> military institutionsin terms of aid delivery, <strong>and</strong> the impact ofthese incentive structures on the effectivedelivery of development assistance.4. Insecurity rather than security isrewardedBecause the primary objective of post-2001 U.S.aid to Afghanistan has not been development forits own sake but rather the promotion of securityobjectives, funding for insecure areas has takenpriority over secure areas. Therefore, the bulk ofU.S. civilian <strong>and</strong> military development assistancefunds in Afghanistan have been spent ininsurgency-affected provinces in the south <strong>and</strong>east. The last several years have seen an evengreater prioritization of the insecure areas despitethe lack of evidence that the aid funds beingspent are promoting stability or improvingattitudes towards the Afghan government <strong>and</strong>the international community. The findings fromthis study <strong>and</strong> other research suggest that aid ismore effectively spent in secure regions wheregood development practice <strong>and</strong> stronger<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 5

oversight is more feasible, <strong>and</strong> less money has tobe spent on security. The research also suggeststhat in areas where insecurity remained chronic<strong>and</strong> governance structures broken, spendingresources (e.g., for road building) risks fuelingcorruption (both perceived <strong>and</strong> real), intercommunalstrife, <strong>and</strong> competition among localpower-brokers. There is evidence that ininsecure areas local strongmen with militias thatwere being paid to provide security recognizedthe need to perpetuate insecurity. Theprioritization of insecure over secure areas is notsurprisingly being bitterly criticized by Afghansliving in more stable areas, who feel they arebeing penalized for being peaceful.Recommendation:• Reverse the current policy of rewarding insecureareas with extensive aid while effectivelypenalizing secure areas where aid money couldbe spent more effectively <strong>and</strong> accountably. Investin secure areas <strong>and</strong>, except for humanitarianassistance, make aid in insecure areas morecontingent on security. While this study did notspecifically examine the demonstration effect thiscould have, it is quite possible that providingincentives for communities to be peaceful wouldbe more effective than the current approach thatis perceived by many Afghans to be rewardinginsecurity.5. Accountability <strong>and</strong> the measurement ofimpact have been undervaluedThe political need for “quick impact” along withinstitutional imperatives to spend money have inmany cases reduced the incentives for carefulevaluation of project impact. Currently it is noteven possible to get a complete list of the projectsPRTs have implemented with the approximately$2.64 billion in CERP funds appropriatedbetween 2004 <strong>and</strong> 2010, let alone an indicationof what the impact has been. The study’sfindings have been reinforced by increasingmedia <strong>and</strong> U.S. agency reports (e.g., SpecialInspector General for AfghanistanReconstruction [SIGAR], USAID Office of theInspector General [OIG]) on funds that havebeen wastefully spent with no (or negative)impact.In an environment with little reliablequantitative data, with numerous independentvariables that make determining correlation (notto mention causality) virtually impossible, <strong>and</strong>where western-style public opinion pollingmethodologies may not be reliable, thedetermination of impact may often have to bemore art than science. Nevertheless, much morefocus should be given to trying to measure theimpact <strong>and</strong> consequences of aid projects than hasbeen done to date. Recent initiatives by SIGAR,OIG, <strong>and</strong> staff at the Senate Foreign RelationsCommittee are positive, but they come late inthe game. In addition to the waste of taxpayerresources <strong>and</strong> negative consequences on theground, the discrediting of all programs forAfghanistan may be collateral damage if aidresources are not spent in a more accountable<strong>and</strong> effective manner.Recommendation:• Reinforce at all levels the message <strong>and</strong> cultureof accountability. This is not arecommendation to add several morebureaucratic levels of cumbersome national<strong>and</strong> international oversight mechanisms tooversee inputs, but rather to invest more inmeasuring outcomes. Establish incentivestructures for quality work <strong>and</strong> carefulassessments of effectiveness <strong>and</strong> not just forspending money.6. Development is a good in <strong>and</strong> of itselfThere is considerable evidence that developmentassistance in Afghanistan during the past decadehas directly contributed to some very positivedevelopment benefits, including decreases ininfant <strong>and</strong> maternal mortality, dramatic increasesin school enrollment rates for boys <strong>and</strong> girls, amedia revolution, major improvements in roads<strong>and</strong> infrastructure, <strong>and</strong> greater connectivitythrough telecommunication networks. Oneconsequence of viewing aid resources first <strong>and</strong>foremost as a stabilization tool or “a weaponssystem” is that these major development gainshave often been under-appreciated because theydid not translate into tangible security gains.U.S. development assistance in Afghanistan hasbeen justified on the grounds that it is promoting6Feinstein International Center

COIN/stabilization objectives rather th<strong>and</strong>evelopment objectives. While in the short termthis has led to much higher levels of developmentassistance in Afghanistan, the failure of theseresources to improve the security situation isnow leading many policymakers to question thevalue of development assistance despite somevery real development gains.Recommendation:• Value development as a good in <strong>and</strong> of itself.Program development aid first <strong>and</strong> foremost topromote development objectives, where thereis evidence of impact <strong>and</strong> effectiveness, ratherthan to promote stabilization <strong>and</strong> securityobjectives, where this research suggests there islittle evidence of effectiveness.<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 7

1. IntroductionU.S. military on patrol, Helm<strong>and</strong>U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. John M. McCall1.1 Purpose, rationale, <strong>and</strong> description ofstudyPolitical <strong>and</strong> national-security considerationshave always influenced U.S. foreign assistancepolicies <strong>and</strong> priorities. Since 9/11, however, thisinfluence has grown greatly, as development aidfor countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, <strong>and</strong> Pakistanhas been increasingly <strong>and</strong> explicitly subsumedunder the national security agenda. The U.S. isnot alone in viewing development through asecurity lens; other Western nations, includingmany of the U.S.’s NATO allies, have, tovarying extents, restructured their aid programsto reflect the prevailing foreign policy agenda ofconfronting global terrorism. The major impactthis has had on development assistance has beenat the policy <strong>and</strong> practice levels. It is reflected inchanging aid strategies, priorities, <strong>and</strong> structures.At the same time, a widely held assumption inmilitary <strong>and</strong> foreign policy circles is thatdevelopment assistance is an important “softpower” 1 tool to win consent <strong>and</strong> to promotestabilization <strong>and</strong> security objectives.Counterinsurgency doctrine in particularemphasizes the importance of humanitarian <strong>and</strong>reconstruction assistance, often in the form of“Quick Impact Projects” that are intended to“win hearts <strong>and</strong> minds.”The assumption that aid projects improvesecurity has had a number of implications,including the sharp increase since 9/11 in theabsolute amount of funding available from bothU.S. <strong>and</strong> other Western donors for humanitarian1The term “soft power“ was coined by Joseph Nye in the 1980s to refer to a nation’s ability to influence the preferences <strong>and</strong> behavior ofother nations not through coercion (hard power), but through projection of attractive national values, levels of prosperity, <strong>and</strong> openness.See Joseph Nye, “The Benefits of Soft Power,” Working Knowledge (Harvard Business School, August 2, 2004), http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/4290.html.8Feinstein International Center

<strong>and</strong> development purposes 2 ; the increasedpercentage of assistance that is programmedbased on strategic security considerations ratherthan on the basis of poverty <strong>and</strong> need; <strong>and</strong> themuch greater role for the military or combinedcivil-military teams in activities that weretraditionally the preserve of humanitarian <strong>and</strong>development organizations. This assumption ishaving a major policy impact on howdevelopment assistance is allocated <strong>and</strong> spent,<strong>and</strong> provides an important rationale for thegrowing “securitization” of developmentassistance. 3 On the one h<strong>and</strong>, military forceshave become increasingly involved in whatwould previously have been seen as the work ofcivilian humanitarian <strong>and</strong> development agencies.On the other h<strong>and</strong>, civilian agencies, includingnon-governmental organizations, have beenincreasingly enlisted in aid <strong>and</strong> developmentprojects that are seen as having stabilizationobjectives. The assumption has been formalizedin the “comprehensive,” “whole of government,”<strong>and</strong> “3D” (diplomacy, defense, development)approaches. (See Section 2 <strong>and</strong> Annex A.)Despite how widespread the assumption is,<strong>and</strong> despite its major impact on aid <strong>and</strong>counterinsurgency policies, there is littleempirical evidence that supports the assumptionthat reconstruction assistance is an effective toolto “win hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” <strong>and</strong> improve securityor increase stability in counterinsurgencycontexts. To help address this lack of evidence,the Feinstein International Center (FIC) at <strong>Tufts</strong><strong>University</strong> conducted a comparative study inAfghanistan <strong>and</strong> the Horn of Africa to examinethe effectiveness of aid projects in promotingsecurity objectives in stabilization <strong>and</strong>counterinsurgency contexts. 4Afghanistan provided an opportunity to examineone of the most concerted recent efforts to use“hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” projects to achieve securityobjectives, especially as it has been the testingground for new approaches to usingreconstruction assistance to promote stability,which in some cases (e.g., ProvincialReconstruction Teams) were then exported toIraq. While other studies have looked at theeffectiveness of aid in promoting humanitarian<strong>and</strong> development objectives as well as the ethical<strong>and</strong> philosophical issues related to merginghumanitarian <strong>and</strong> security objectives,surprisingly little effort has been given toanalyzing the effectiveness of aid in promotingpolitical <strong>and</strong> security objectives. Given that asignificant percentage of U.S. foreign aid is nowprogrammed (both explicitly <strong>and</strong> implicitly) toachieve security objectives, the need todetermine the effectiveness of this use ofdevelopment assistance is real. 5While aid projects are not all designed withstabilization objectives in mind, the study did notdistinguish between military <strong>and</strong> non-military aid,although in some cases it focused more on militarylinkedaid. While projects that had an explicitstabilization focus might have been of specialinterest, the broad point is that aid in general isassumed to promote stability. Also, while the U.S.is the largest donor <strong>and</strong> has increased its aidspending by the largest percentage post-2001, thestudy did not intend to be primarily U.S.-focused;therefore, it looked at all aid.2According to Center for Global Development statistics, between 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2009 U.S. official development assistance more than doubled inreal terms, while Donor Assistance Committee countries’ assistance increased by more than half. See Net Aid Transfers data set (1960–2009), http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/5492.3The terminology of the “securitization of aid” <strong>and</strong> much of its intellectual underpinning has been provided by Professor Mark Duffield,who uses it to describe the important role of development aid to support a new system of global governance that helps protect westernsecurity interests. Rather than being primarily about helping the poor through alleviating poverty <strong>and</strong> promoting development, Duffieldargues that aid is increasingly being used as a governance <strong>and</strong> security tool to help stabilize <strong>and</strong> govern unstable <strong>and</strong> borderl<strong>and</strong> regions sothat they do not threaten the West’s way of life. See, for example, Mark Duffield, “Governing the Borderl<strong>and</strong>s: Decoding the Power ofAid,” Disasters, Volume 25, Issue 4, (December 2001), pp. 308-320; Mark Duffield, Global Governance <strong>and</strong> the New Wars: The Merging ofDevelopment <strong>and</strong> Security, (London: Zed Books, 2001); <strong>and</strong> Mark Duffield, Development, Security <strong>and</strong> Unending War: Governing the World ofPeoples, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007).4This paper focuses on the findings from Afghanistan. For information on findings from the Horn of Africa, see https://wikis.uit.tufts.edu/confluence/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=34807224. For information on the overall aid <strong>and</strong> security research program, see https://wikis.uit.tufts.edu/confluence/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=19270958.5A March 2010 conference co-sponsored by Feinstein International Center on the use of development aid in COIN operations inAfghanistan noted that “a key theme is the critical lack of monitoring, evaluation, <strong>and</strong> empirical data available to assess the impact of aid onstability in Afghanistan,” especially given the “otherwise strong traditions of robust after-action reviews” by the military. See Wilton Park,“<strong>Winning</strong> ‘<strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>’ In Afghanistan: Assessing the Effectiveness of Development Aid in COIN Operations,” Report on WiltonPark Conference 1022, held March 11–14, 2010 (July 22, 2010). http://www.wiltonpark.org.uk/resources/en/pdf/22290903/22291297/wp1022-report.<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 9

After presenting the study methodology below,the paper continues in Section 2 with adiscussion of the evolution of security-driven aid<strong>and</strong> the effects on current practice. Section 3describes the five provinces included in the study<strong>and</strong> how different models of securitizeddevelopment have been used in each of them.Sections 4 <strong>and</strong> 5 present the views obtained inthe field on the causes of insecurity <strong>and</strong> thecharacteristics of aid projects. Section 6 discussesthe effectiveness of aid in stabilization inAfghanistan, <strong>and</strong> Section 7 summarizes thestudy’s conclusions <strong>and</strong> policy implications. Moredetailed information on the researchmethodology <strong>and</strong> related issues is contained inAnnex A.1.2 MethodologyResearch was conducted in the five provinces ofBalkh, Faryab, Helm<strong>and</strong>, Paktia, <strong>and</strong> Uruzgan,as well as in Kabul city. In these provinces, as innearly all of Afghanistan’s thirty-four provinces,international civilian <strong>and</strong> military actors areusing humanitarian, reconstruction, <strong>and</strong>development aid to promote greater stability <strong>and</strong>security. The notable differences among the fiveprovinces provided the opportunity to examinethe development-security nexus in very differentcontexts. Balkh <strong>and</strong> Faryab Provinces in thenorth were much more secure than Helm<strong>and</strong>,Uruzgan, <strong>and</strong> Paktia Provinces in the south <strong>and</strong>southeast where the Taliban-led insurgency wasmore active. In the two northern provinces,Pashtuns are a minority ethnic group, whereas inthe south <strong>and</strong> southeast they make up theoverwhelming majority. Another significantdifference was the variations in approach,budgetary resources, <strong>and</strong> character of thedifferent NATO/ISAF (International SecurityAssistance Force) nations heading the ProvincialReconstruction Teams (PRTs) in eachprovince—with perhaps the major difference forthe purposes of this study being the much greaterfinancial resources available to U.S.-led PRTs.The study teams used a relatively consistentmethodology in four of the five provincial studyareas (Helm<strong>and</strong> being the exception), bearing inmind that the varied security <strong>and</strong> otherconditions allowed or required approachestailored to different areas. Qualitative interviewswith Afghan <strong>and</strong> international respondents inthe field provided the primary data source.Interviews were conducted during multiplevisits to the provinces between June 2008 <strong>and</strong>February 2010. In the four provinces as well asin Kabul, a total of 574 respondents (340Afghan, 234 international) were interviewedeither individually or in focus groups at theprovincial, district, <strong>and</strong> community levels.Separate semi-structured interview guides wereused for key informant <strong>and</strong> community-levelinterviews. Respondents included current <strong>and</strong>former government officials, donors, diplomats,international military officials, PRT military<strong>and</strong> civilian staff, UN <strong>and</strong> aid agency staff,tribal <strong>and</strong> religious leaders, journalists, traders<strong>and</strong> businessmen, <strong>and</strong> community members. InHelm<strong>and</strong>, the methodology consisted ofanalyzing qualitative data from focus groupsconducted in February-March 2008,quantitative data taken from polling data drawnfrom communities in November 2007 <strong>and</strong>provided by the PRT, <strong>and</strong> interviews with keyinformants (e.g., PRT staff, Afghan governmentofficials). Most of the interviews with Afghanswere conducted in Dari or Pashtu, althoughsome with senior government <strong>and</strong> NGOofficials were conducted in English. The twointernational researchers leading the fieldresearch in Balkh <strong>and</strong> Faryab Provinces wereexcellent Dari speakers <strong>and</strong> could directlyinterview Afghan respondents. Afghan researchassistants helped in setting up <strong>and</strong> conductinginterviews, as well as in note taking <strong>and</strong>analysis. Elsewhere, research assistants ortranslators assisted researchers in translatingDari <strong>and</strong> Pashtu. In all provinces, secondarysources were drawn upon for historicalinformation <strong>and</strong> background to aid projects.The Balkh, Faryab, <strong>and</strong> Uruzgan case studiesbenefited from background historical <strong>and</strong>political overviews written by leading analystsof these provinces.Any research in Afghanistan or other conflictareas requires caution because of the potentialfor respondent bias. This is particularly the casefor research that looks at the types of sensitiveissues raised in this study or includes questionsthat relate to deeply held social norms. Tomitigate these potential biases, the methodologyincluded repeat visits to allow follow-up to <strong>and</strong>10Feinstein International Center

triangulation of responses, flexible interviewguides that encouraged spontaneous responseswithin specific themes, <strong>and</strong> the fielding ofteams with extensive local experience.The study relied primarily on the statedperceptions of the wide range of respondentsmentioned above. Where relevant, thediscussion differentiates the perspectives ofdifferent types of actors. The researchersacknowledge the need for caution when basingfindings on the stated perceptions ofrespondents, as respondents’ statements may notalways accurately reflect their perceptions <strong>and</strong>,in addition, may not match behavior. The studyalso did not aim to measure causality, as thiswas simply too ambitious in an environmentwith so many confounding variables. Still,because aid projects explicitly aim to changeattitudes, perceptions (if captured accurately)are relevant. Moreover, however imperfect, theresearch team believed that in the Afghancontext the qualitative data gathered in indepthinterviews provided a better data source<strong>and</strong> gauge of perceptions than most datacollected using quantitative methodologies,such as public opinion polling.Since the field research was completed in early2010, a number of the issues raised by thefindings have been acknowledged by the U.S.<strong>and</strong> by ISAF, <strong>and</strong> some measures have beentaken to mitigate them, as discussed in the text.Security conditions have also changedsomewhat. While Balkh <strong>and</strong> Faryab are stillrelatively secure, insecurity has widened in thenorth in general, <strong>and</strong> in the troubled districts inthe provinces of Balkh <strong>and</strong> Faryab in particular.On the other h<strong>and</strong>, security in areas ofHelm<strong>and</strong> has improved since the time of theresearch. Nevertheless, based on more recentvisits <strong>and</strong> discussions as well as the analysis ofothers’, the researchers feel that the broadconclusions <strong>and</strong> concerns remain valid <strong>and</strong> verypolicy-relevant.Additional information on the researchmethodology <strong>and</strong> related issues is contained inAnnex A.1.3 Similar <strong>and</strong> related research inAfghanistanA number of other studies <strong>and</strong> evaluationsexamining the effect of development activitieson security have been conducted in Afghanistanat the same time or later than this one. One ofthe most comprehensive, conducted by ChristofZürcher, Jan Koehler, <strong>and</strong> Jan Böhnke innortheastern Takhar <strong>and</strong> Kunduz Provincesbetween 2005 <strong>and</strong> 2009, concluded thatcommunities that already felt more secure weremore likely to feel positively about aid, <strong>and</strong> thatany positive effects of aid on the population’sattitude towards the state are “short-term” <strong>and</strong>“non-cumulative.” 6 Similarly, researchconducted in 2009 by Sarah Ladbury inK<strong>and</strong>ahar, Wardak, <strong>and</strong> Kabul Provinces foundthat young men joined the insurgency for acomplex combination of reasons, some personal<strong>and</strong> some related to broader grievances againstthe government <strong>and</strong> foreign forces.Development projects were seen as being toosmall to have any impact, <strong>and</strong> as unemployment(or underemployment) was one factor leading tomobilization, respondents expressed the desirefor projects that created employment. The poorquality of aid delivery suggested that moreattention be paid to how services are delivered. 7A quantitative study done with the support ofthe U.S. Army using district-level data for the2002–10 period found that while projects canaffect the number of security incidents in adistrict, in most cases their influence is so smallas to not justify using them as a conflictmitigationtool. 8 Finally, a report prepared inJune 2011 for the use of the U.S. Senate ForeignRelations Committee concluded, afterexamining the evidence from several studies(including the present one <strong>and</strong> those mentionedabove), that “the evidence that stabilization6J. Böhnke, J. Koehler <strong>and</strong> C. Zürcher, “Assessing the Impact of Development Cooperation in North East Afghanistan 2005–2009: FinalReport,” Evaluation Reports 049 (Bonn: Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammen arbeit und Entwicklung, 2010).7Sarah Ladbury, in collaboration with Cooperation for Peace <strong>and</strong> Unity (CPAU), “Testing Hypotheses on Radicalisation in Afghanistan:Why Do Men Join the Taliban <strong>and</strong> Hizb-i Islami? How Much Do Local Communities Support Them?” Independent Report for theDepartment of International Development (August 2009).8Schaun Wheeler <strong>and</strong> Daniel Stolkowski, “Development as Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan,” Unpublished manuscript (Draft dated June17, 2011).<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 11

Photo by Shirine Bakhat-PontISAF patrol passing through Mazar-e Sharifprograms promote stability in Afghanistan islimited . . . [The] unintended consequences ofpumping large amounts of money into a warzone cannot be underestimated.” 9 One study thatdid show some impact of development assistanceon security perceptions was a World Bankfundedstudy of the National Solidarity Program(NSP) conducted in villages outside of the mainconflict areas between 2007 <strong>and</strong> 2011 by AndrewBeath <strong>and</strong> his colleagues. The study found thatthe NSP had overall positive effects oncommunities’ perceptions of economic wellbeing,all levels of government (except thepolice), <strong>and</strong> non-governmental organizations(NGOs), the security situation, <strong>and</strong> (weakly)international forces. This study did not, however,find measurable improvements in actual security,although it looked only at short-term outcomes. 10These studies are discussed further in Section 6below.9Majority Staff, Foreign Relations Committee, United States Senate, “Evaluating U.S. Foreign Assistance to Afghanistan,” (June 8, 2011), p. 2,http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html.10Andrew Beath, Fotini Christia, <strong>and</strong> Ruben Enikolopov, “<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Afghanistan,”Working Paper No. 2011-14 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Political Science Department, undated).12Feinstein International Center

2. Evolution of security-driven aid 11Photo by Cpl. Jeff DrewU.S. military inspecting school construction, Helm<strong>and</strong>The role of militaries in delivering aid <strong>and</strong>reconstruction is not a new phenomenon. Whathas changed, especially since 2001, is the scale ofthe involvement <strong>and</strong> the purposes underpinningit. According to the Organization for EconomicCo-operation <strong>and</strong> Development (OECD),between 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2005, USAID’s share of U.S.official development assistance (ODA) decreasedfrom 50 to 39 percent, while the share of theDepartment of Defense (DOD) increased from 6to 22 percent. 12 While more recent OECD datanow show DOD’s global share of U.S. ODA tobe shrinking, it still plays a dominant role inAfghanistan. Between 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2010, nearly $38billion was appropriated to “stabilize <strong>and</strong>strengthen the Afghan economic, social,political, <strong>and</strong> security environment so as to bluntpopular support for extremist forces in theregion.” 13 Roughly half of this has gone totraining <strong>and</strong> equipping the Afghan NationalSecurity Forces (ANSF), while a little overone-third has gone to economic, social, political,<strong>and</strong> humanitarian efforts. Of the total amount,nearly two-thirds has been allocated to theDOD, with USAID <strong>and</strong> the Department of Statereceiving lesser amounts. One specific indicatorof the importance of security-driven aid is thedramatic growth of the Comm<strong>and</strong>ers’Emergency Response Program (CERP) 14funding in Afghanistan, from zero in 2003 to$1.2 billion in 2010 (Figure 1).11The authors would like to acknowledge the very substantive contribution of Dr. Stuart Gordon to this section.12OECD, “DAC Peer Review: Main Findings <strong>and</strong> Recommendations, Review of the Development Co-operation Policies <strong>and</strong>Programmes of United States” (2006), https://www.oecd.org/document/27/0,2340,en_2649_34603_37829787_1_1_1_1,00.html.13Curt Tarnoff, “Afghanistan: U.S. Foreign Assistance” (Congressional Research Service, August 12, 2010).14CERP is a U.S. military program which provides discretionary funds for PRT comm<strong>and</strong>ers to execute local small-scale relief <strong>and</strong>reconstruction projects. Projects are intended to build good will, trust, <strong>and</strong> confidence between the local population <strong>and</strong> the internationalmilitary, thereby increasing the flow of intelligence <strong>and</strong> turning the population against the insurgents <strong>and</strong> other anti-government groups.CERP is discussed further below <strong>and</strong> in Box 2.<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 13

Figure 1Source: Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction,“Quarterly Report to the U.S. Congress” (April 30, 2011),142–3.The contemporary origins of militaryinvolvement in delivering assistance lie in theAllied preparations for the invasions of NorthAfrica <strong>and</strong> Western Europe in the course ofWorld War II. However, it is perhaps morestrongly associated with the Cold Warcounterinsurgency campaigns of the 1950sthrough the 1970s, principally the Britishexperiences in Malaya, Oman, <strong>and</strong> Aden(Yemen), <strong>and</strong> the U.S. experience in Vietnam.The phrase “hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” is usuallyassociated with Field Marshal Sir GeraldTempler, 15 <strong>and</strong> his ultimately successful conductof the British-led counter insurgency campaignin Malaya (1948–60). Since the “MalayanEmergency,” the phrase has often been used as aform of shorth<strong>and</strong> for the overall Britishapproach to counter-insurgency: emphasizingwinning the “hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” of thepopulation through securing the support of thepeople. The approach shaped British strategyboth in Malaya <strong>and</strong> in dealing with the MauMau rebellion in Kenya. In the 1970s, it wasinfluential in Northern Irel<strong>and</strong>. The kernel ofthe strategy was to establish secure zones, useminimum force, apply development, <strong>and</strong> addresspolitical grievances that underlay the rebellions— all in order to turn the population against theinsurgents. At the same time, outside of thesecure areas, the strategy was to implementmilitary measures designed to inflict attrition onthe military component of the insurgency. Thisapproach has been contrasted with tactics thatstress more conventional military means, are lessfocused on developing the support of thepopulation, <strong>and</strong> are less concerned with avoidingcivilian casualties.The U.S. experience began as Civil Affairs inWorld War II but has echoed the British path inits association with counter-revolutionary warfare,particularly in programs such as the CivilOperations <strong>and</strong> Revolutionary DevelopmentSupport Program (or CORDS) during theVietnam War. These counter-insurgencyapproaches tended to bring together efforts toseparate the population from the insurgents whileproviding a variety of reconstruction programs towin over the sympathy of the population. Thephrase “hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” was also associatedwith the U.S. military <strong>and</strong> strategies adopted tocontain the communist insurgency in Vietnam.President Lyndon B. Johnson is quoted in May1965 when he argued that U.S. victory would bebuilt on the “hearts <strong>and</strong> minds of the people whoactually live out there. By helping to bring themhope <strong>and</strong> electricity you are also striking a veryimportant blow for the cause of freedomthroughout the world.” 16 This approach shapedboth U.S. strategy <strong>and</strong> rhetoric on the war inIndo-China <strong>and</strong> led to efforts to coordinatedevelopment <strong>and</strong> security approaches that wouldcounter communist propag<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> isolate theinsurgents from the people. Under Johnson theU.S. “committed itself to ‘pacification’ of SouthVietnam by providing both security <strong>and</strong>development support. U.S. officials, both civilian<strong>and</strong> military, would provide ‘advice’ <strong>and</strong> resourcesfor economic development projects, such asrebuilding roads <strong>and</strong> bridges, while the militarywould train <strong>and</strong> equip South Vietnam’s police <strong>and</strong>paramilitary groups to hunt down insurgents.” 1715John Cloake, Templer: Tiger of Malaya: The Life of Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer (London: Harrap, 1985). Footnote 1 states that Templerfirst used the term on April 26, 1952.16Lyndon B. Johnson quoted in Francis Njubi Nesbitt, “<strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong> <strong>and</strong> Empire.” Foreign Policy in Focus (March 20, 2009), http://www.fpif.org/articles/hearts_<strong>and</strong>_minds_<strong>and</strong>_empire.17Ibid.14Feinstein International Center

2.1 Current approachesRecognition that the causes of instability arecomplex has driven the formulation of the variousmodels, such as the“ comprehensive approach,”“3D” (defense, diplomacy, development), “wholeof government,” <strong>and</strong> “integrated approach.”These trends are discernible in a range ofinternational organizations (particularly the EU<strong>and</strong> NATO) as well as between <strong>and</strong> withinministries in individual states. For example, in2004, the UK government established a Post-Conflict Reconstruction Unit (renamed theStabilisation Unit in 2007), jointly owned by theMinistry of Defense (MOD), Foreign <strong>and</strong>Commonwealth Office (FCO) <strong>and</strong> Departmentfor International Development (DFID); in 2004,the U.S. Congress appropriated funds for the U.S.State Department to establish the Office of theCoordinator for Reconstruction <strong>and</strong> Stabilization(S/CRS); <strong>and</strong> in 2005, the Canadian governmentestablished the Stabilisation <strong>and</strong> ReconstructionTask Force (START) within its Department ofForeign Affairs <strong>and</strong> International Trade.The various models are all derived from thesense that the origins of conflict are largelysocio-economic in nature, <strong>and</strong> that state failureis a consequence of the breakdown of publicservice delivery. Militaries have been attractedto comprehensive or integrative approaches fora variety of reasons related both to theories ofconflict causation <strong>and</strong> resolution <strong>and</strong> to thenecessity for “soft power” to contribute to“force protection.” 18 In terms of theories aboutwhat causes conflicts <strong>and</strong> how they are resolved,conflict is frequently portrayed as a product oflow levels of development as well as political<strong>and</strong> social marginalization. In the course of aninternational military intervention, it is oftenassumed that tactical military progress cannotbe consolidated or translated into strategicsuccess, <strong>and</strong> viable states cannot be built,without the host government constructinglegitimacy through the provision of publicservices. In terms of force protection, thetheory is that when an international militaryforce provides infrastructure <strong>and</strong> “facilities”(such as public health clinics, wells, <strong>and</strong> schools)the population will be encouraged intocollaborative relationships with theinternational military—reducing opportunitiesfor insurgents <strong>and</strong> providing intelligence to thecounter-insurgent forces.The U.S. DOD has made considerable efforts todevelop the capacities for “stability operations” 19<strong>and</strong> to link these with the work of theDepartment of State <strong>and</strong> USAID—the result isan approach to security that makes afundamental break with the past. The principalchange has been a reorientation to meet adifferent perceived threat. The 2002 U.S.National Security Strategy stated that the U.S.“is now threatened less by conquering statesthan we are by failing ones.” Then Secretary ofDefense, Robert M. Gates, argued that even theemphasis on regime change that dominatedbetween 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2003 had changed:Repeating an Afghanistan or an Iraq—forcedregime change followed by nation-building underfire—probably is unlikely in the foreseeablefuture. What is likely though, even a certainty, isthe need to work with <strong>and</strong> through localgovernments to avoid the next insurgency, torescue the next failing state, or to head off thenext humanitarian disaster.Correspondingly, the overall posture <strong>and</strong> thinkingof the United States armed forces has shifted—away from solely focusing on direct Americanmilitary action, <strong>and</strong> towards new capabilities toshape the security environment in ways that obviatethe need for military intervention in the future. 20In 2005 the DOD issued “DOD Directive3000.05” (2005), emphasizing the importance18Force protection consists of preventive measures intended to reduce hostile actions against military personnel, resources, facilities, <strong>and</strong>information.19DOD defines stability operations as “An overarching term encompassing various military missions, tasks, <strong>and</strong> activities conducted outsidethe United States in coordination with other instruments of national power to maintain or reestablish a safe <strong>and</strong> secure environment,provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, <strong>and</strong> humanitarian relief.” See Headquarters Departmentof the Army, “Stability Operations,” FM 3-07 (December 2008), Glossary, p. 9.20Robert M. Gates. (U.S. Secretary of Defense) “U.S. Global Leadership Campaign.” Speech given on July 15, 2008 at the U.S. GlobalLeadership Campaign (Washington, DC). http://www.defenselink.mil/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1262.<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 15

of stability operations asa core U.S. military mission that the Department ofDefense shall be prepared to conduct <strong>and</strong> support.They shall be given priority comparable to combatoperations <strong>and</strong> be explicitly addressed <strong>and</strong> integratedacross all DOD activities including doctrine,organizations, training, education, exercises,materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, <strong>and</strong>planning. 21The directive emphasized that “stabilityoperations were likely to be more important tothe lasting success of military operations thantraditional combat operations” <strong>and</strong> “elevatedstability operations to a status equal to that of theoffense <strong>and</strong> defense.” 22 This represented asignificant reorientation of the U.S. military’straditional focus on “warfighting.”More recently, this emphasis on the identificationof instability in other states as a threat to U.S.interests was reflected in both the 2008 NationalDefense Strategy <strong>and</strong> the 2010 QuadrennialDefense Review (QDR), which noted that“preventing conflict, stabilizing crises, <strong>and</strong>building security sector capacity are essentialelements of America’s national securityapproach.” 23 Underst<strong>and</strong>ably, this thinking hasplayed an important role in driving forcepreparations within the DOD, strengthening thesignificance of stability operations <strong>and</strong>broadening the range of competencies thatwould be required in a future U.S. military.The changing emphasis in the U.S. is alsoconsistent with the changing nature of UNpeacekeeping missions, increasinglycharacterized by complex m<strong>and</strong>ates spanning“immediate stabilization <strong>and</strong> protection ofcivilians to supporting humanitarian assistance,organizing elections, assisting the developmentof new political structures, engaging in securitysector reform, disarming, demobilizing <strong>and</strong>reintegrating former combatants <strong>and</strong> laying thefoundations of a lasting peace.” 24 This integrationof diplomatic, human rights, military, <strong>and</strong>development responses has been driven primarilyby the requirement to effectively consolidatefragile peace agreements <strong>and</strong> make the delicatetransition from war to a lasting peace 25 —thefragility of peace often being “ascribed to a lackof strategic, coordinated <strong>and</strong> sustainedinternational efforts.” 26 A significant amount ofliterature documents the increasing size <strong>and</strong>complexity of, particularly, the civiliancomponents of peace missions 27 (arguablybeginning with the deployment of the UNTAGmission in Namibia in 1989 28 ) <strong>and</strong> thediversification <strong>and</strong> growing importance ofnon-military tasks within UN m<strong>and</strong>ates. Evenwhere the UN has deployed solely civilianmissions, their proximity <strong>and</strong> relationship tomilitary, peace-building, or state-buildingmissions in support of a government authorityhas raised the same issue for some critics: theassociation of humanitarian <strong>and</strong> developmentresponses with one of the belligerentsundermines the UN’s independence <strong>and</strong>neutrality.Despite the lack of evidence that “hearts <strong>and</strong>minds” activities can generate attitude orbehavior change, these broader strategic trends21“DOD, Directive 3000.05: Military Support for Stability, Security, Transition, <strong>and</strong> Reconstruction (SSTR) Operations” (November 28,2005). p.2. As noted on the next page, the directive also clarifies that DOD sees its role in U.S. government plans for SSTR as part ofinteragency partnerships.22FM 3-07, “Stability Operations,” p. vi.23Lauren Ploch, “Africa Comm<strong>and</strong>: U.S. Strategic Interests <strong>and</strong> the Role of the U.S. Military in Africa” (Congressional Research Service,July 22, 2011), http://opencrs.com/document/RL34003/24Espen Barth Eide, Anja Therese Kaspersen, R<strong>and</strong>olph Kent, <strong>and</strong> Karen von Hippel, “Report on Integrated Missions: PracticalPerspectives <strong>and</strong> Recommendations,” Independent Study for the Exp<strong>and</strong>ed UN ECHA Core Group (May 2005), p. 3.25“In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security <strong>and</strong> Human Rights for All,” A/59/2005 (March 21, 2005), paragraph 114.26Eide et al., “Report on Integrated Missions,” p. 3.27For more on the changing nature of peace operations, see Bruce Jones <strong>and</strong> Feryal Cherif, “Evolving Models of Peacekeeping: PolicyImplications <strong>and</strong> Responses,” (Center on International Cooperation, NYU, September 2003), http://www.peacekeepingbestpractices.unlb.org/.28The United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) was a UN peacekeeping force deployed in April 1989 with a very broadmission in the transition from then South-West Africa to an independent Namibia. See, United Nations, “Namibia – UNTAGBackground” (undated), http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/untagFT.htm.16Feinstein International Center

Photo by Cpl. Andrew CarlsonU.S. military <strong>and</strong> construction, Helm<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> the hearts <strong>and</strong> minds approach have had adramatic impact on doctrine <strong>and</strong> tactics relatedto stabilization <strong>and</strong> on the organization of theU.S. military. Department of Defense Directive(DODD) 3000.05 defined the broad objectivesof stability operations, stating that theirimmediate goal was to “provide the localpopulace with security, restore essential services,<strong>and</strong> meet humanitarian needs. Long-term goalsthat reflect transformation <strong>and</strong> fostersustainability efforts include developing hostnationcapacity for securing essential services, aviable market economy, rule of law, legitimate<strong>and</strong> effective institutions, <strong>and</strong> a robust civilsociety.” 29 The U.S. Army’s manual, Tactics inCounterinsurgency, states that “at its heart acounterinsurgency is an armed struggle for thesupport of the population.” 30 This populationcentricview of conflict is rooted in theassumption that conditions such as poverty,unemployment, illiteracy, <strong>and</strong> unmet aspirationsare the fuels that drive insurgencies <strong>and</strong> that theremedy is humanitarian, reconstruction, <strong>and</strong>development assistance. The idea underpinningthese perspectives is that project-based assistance,including small-scale “Quick Impact Projects,”can capture the “hearts <strong>and</strong> minds” ofbeneficiary populations <strong>and</strong> lead to both achange of attitude towards the government <strong>and</strong>increasing co-operation with the internationalmilitary. The latter is most likely to be seen interms of intelligence sharing—e.g., identifyingimprovised explosive devices (IEDs) or providinginformation on insurgents—a key component inprotecting one’s own forces. The deterioratingsecurity situation in parts of Afghanistan, whichforced many traditional humanitarian <strong>and</strong>development organizations to suspend activities<strong>and</strong> withdraw staff, also contributed to thegrowing role of the military <strong>and</strong> PRTs indirectly supporting reconstruction <strong>and</strong>development activities as they felt compelled tostep into the void. 3129FM3-07, “Stability Operations,” p. 1-1530U.S. Department of the Army, Tactics in Counterinsurgency, FM 3-24.2 (April 2009), p. ix.31Stewart Patrick <strong>and</strong> Kaysie Brown, “The Pentagon <strong>and</strong> Global Development: Making Sense of the DOD’s Exp<strong>and</strong>ing Role,” WorkingPaper Number 131 (November 2007).<strong>Winning</strong> <strong>Hearts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Minds</strong>? Examining the Relationship between Aid <strong>and</strong> Security in Afghanistan 17

The need to develop interagency partnershipshas been a recurring theme across recent U.S.security policy. 32 In the preface to FM 3-07“Stability Operations,” Lieutenant GeneralCaldwell, argues that at the heart of the programto enhance stability operations is “acomprehensive approach . . . that integrates thetools of statecraft with our military forces,international partners, humanitarianorganizations, <strong>and</strong> the private sector.” 33 The sumof these changes is an organizationalreconfiguration around a military capable ofintervening in fragile states <strong>and</strong> having thepotential to assume responsibility for a range oftasks that had traditionally been delivered bygovernment civilian agencies <strong>and</strong> development<strong>and</strong> humanitarian organizations. While thisguidance recognized that “many stabilityoperations tasks are best performed byindigenous, foreign, or U.S. civilianprofessionals,” it situated the militarystabilization response within a broader “whole ofgovernment” 34 approach, but made clear that“U.S. military forces shall be prepared toperform all tasks necessary to establish ormaintain order when civilians cannot do so.”Officially, U.S. development agencies haveembraced this relationship. According to USAIDAdministrator Rajiv Shah, “in the most volatileregions of Afghanistan, USAID works side-bysidewith the military, playing a critical role instabilizing districts, building responsive localgovernance, improving the lives of ordinaryAfghans, <strong>and</strong>—ultimately—helping to pave theway for American troops to return home.” 35While policy has referred to “partnerships” <strong>and</strong>integration of military <strong>and</strong> civilian agencies, themilitary’s relationship with the civilian branchesof government <strong>and</strong> the external humanitariancommunity is unlikely to be an equal one. AU.S. military with significantly more financial,personnel, <strong>and</strong> material resources, <strong>and</strong> fargreater reach than either USAID or the StateDepartment, inevitably makes the military’s rolestrong <strong>and</strong> potentially dominant.While the Afghan <strong>and</strong> Iraqi funding surges areclearly only temporary, DOD’s approach tostabilization, <strong>and</strong> the significant role of themilitary in delivering ODA, is likely to endure. 36Some argue that the DOD’s exp<strong>and</strong>ed assistanceauthorities” threaten to “displace or overshadowbroader U.S. foreign policy <strong>and</strong> developmentobjectives in target countries <strong>and</strong> exacerbate thelongst<strong>and</strong>ing imbalance between the military<strong>and</strong> civilian components of the U.S. approach tostate-building.” 37The focus on integrated <strong>and</strong> comprehensiveapproaches to secure the support of thepopulation has led humanitarian <strong>and</strong>development actors to criticize both stabilization<strong>and</strong> counterinsurgency doctrines for leaving littleroom for the fundamental humanitarianprinciples of independence, impartiality, <strong>and</strong>neutrality. Assistance is increasinglyinstrumentalized behind security <strong>and</strong> politicalobjectives. Patrick <strong>and</strong> Brown argue that thesetrends are potentially damaging <strong>and</strong> raiseconcerns that “U.S. foreign <strong>and</strong> developmentpolicies may become subordinated to a narrow,short-term security agenda at the expense ofbroader, longer-term diplomatic goals <strong>and</strong>institution-building efforts in the developingworld.” 38Many aid practitioners <strong>and</strong> agencies areconcerned by the increased politicization <strong>and</strong>securitization of aid because this violates32As featured in the National Military Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, <strong>and</strong> the 2010 QDR: DOD, The Quadrennial Defense ReviewReport (February 2010), p. 73. The FY2011 Defense Budget Request is available at http://www.defenselink.mil/comptroller/budget.html.33Lieutenant General <strong>and</strong> former Comm<strong>and</strong>er of the U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, William H. Caldwell, as quoted in the preface toFM 3-07 “Stability Operations.”34DOD defines “whole of government” as “an approach that integrates the collaborative efforts of the departments <strong>and</strong> agencies of theUnited States Government to achieve unity of effort toward a shared goal.” See FM3-07, “Stability Operations,” Glossary, p. 10.35Cited in Scott Dempsey, “Is Spending the Strategy?” Small Wars Journal (May 4, 2011), p. 2. http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/is-spending-the-strategy.36Some respondents for this study questioned whether this exp<strong>and</strong>ed role has been accepted wholeheartedly as being of equal status by themilitary, or whether there will be resistance <strong>and</strong> reconsideration in light of experience in Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> elsewhere.37Scott Dempsey.38Stewart Patrick <strong>and</strong> Kaysie Brown.18Feinstein International Center