Managerial stress, job satisfaction and health in Taiwan

Managerial stress, job satisfaction and health in Taiwan

Managerial stress, job satisfaction and health in Taiwan

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

STRESS MEDICINEStress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)MANAGERIAL STRESS, JOB SATISFACTIONAND HEALTH IN TAIWANLUO LU, DPhil 1 *, HUI-JU TSENG, MSc 1 AND CARY L. COOPER, PhD 21 Graduate Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Kaohsiung Medical College, Kaohsiung, <strong>Taiwan</strong>2 University of Manchester Institute of Science <strong>and</strong> Technology, Manchester, UKSUMMARYThis study tested an <strong>in</strong>tegrative work <strong>stress</strong> model us<strong>in</strong>g data from a heterogeneous sample of <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers.Results <strong>in</strong>dicated that these managers were under considerable work <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> were at risk of mental <strong>and</strong> physical ill<strong>health</strong>.Internal control was related to higher <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> was bene®cial to mental <strong>health</strong>; however, its<strong>in</strong>teraction with work <strong>stress</strong> was detrimental to psychological well-be<strong>in</strong>g. A speci®c facet of Type A behaviourpattern was also related to poorer physical <strong>health</strong>. These results were discussed with an emic emphasis, tak<strong>in</strong>gaccount of some dist<strong>in</strong>ctive characteristics of the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese culture. Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.KEY WORDS Ð managerial <strong>stress</strong>; <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>; <strong>health</strong>Stress has become one of the most serious <strong>health</strong>issues of the twentieth century Ð a problem notjust for <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> terms of physical <strong>and</strong> mentalmorbidity but also for employers, governments <strong>and</strong>society at large, who have started to assess its®nancial damage. 1 Matteson <strong>and</strong> Ivancevich 2estimate that <strong>stress</strong> causes half of absenteeism,40 percent of turnover, <strong>and</strong> that 5 percent of thetotal workforce covers for reduced productivity dueto preventable <strong>stress</strong>-related illnesses ($60 billionfor the US economy annually). Although othersources may quote di€erent ®gures, it is obviousthat occupational <strong>stress</strong> has serious consequencesfor both <strong>in</strong>dividual employees <strong>and</strong> organizations.The problem of occupational <strong>stress</strong> is particularlyrelevant for countries undergo<strong>in</strong>g enormouseconomic <strong>and</strong> social changes. <strong>Taiwan</strong> is one suchsociety, with a transformation of the <strong>in</strong>dustrialstructure from labour-<strong>in</strong>tensive to high-tech, aswell as rapid westernization <strong>in</strong> both work <strong>and</strong> lifestyle.In this context, recent empirical evidence hasalready shown that compared to British <strong>in</strong>dustrial*Correspondence to: Dr. L. Lu, Graduate Institute ofBehavioural Sciences, Kaohsiung Medical College, 100 Shih-Chuan 1st Road, Kaohsiung City 807, <strong>Taiwan</strong>, ROC. Tel: 886-7-3121101, Ext. 2273. Fax: 886-7-3223445/886-7-2723802.e-mail: luolu@cc.kmc.edu.tw or luolu@mail.nsysu.edu.twContract grant sponsor: CAPCO Cultural <strong>and</strong> EducationalFoundation, <strong>Taiwan</strong>.workers, a large r<strong>and</strong>om sample of their <strong>Taiwan</strong>esecounterparts (N ˆ 1054) has su€ered worsephysical <strong>health</strong> <strong>and</strong> reported better mental <strong>health</strong><strong>and</strong> a similar level of <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>. 3 This stra<strong>in</strong>pattern ®ts well with the somatization thesis forillness behaviour among Ch<strong>in</strong>ese. 4 In a culture of`face', compla<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>stress</strong>-related physical illnessare less stigmatized <strong>and</strong> hence more sociallyacceptable than those of psychological problems. 5,6In another study, a very considerable proportion of<strong>Taiwan</strong>ese cl<strong>in</strong>ical nurses su€ered mental (one <strong>in</strong>11) <strong>and</strong> physical ill-<strong>health</strong> (one <strong>in</strong> four) at a levelcomparable to British psychiatric patients. 7 Onceaga<strong>in</strong>, the pattern is similar. It seems that workers<strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> are su€er<strong>in</strong>g from occupational <strong>stress</strong>just like their Western counterparts, hence moreconcerted research e€orts concern<strong>in</strong>g work <strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>Taiwan</strong> are clearly worthwhile.Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, few studies have exam<strong>in</strong>ed theoccupational <strong>stress</strong> of managers <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong>,particularly at the level of middle <strong>and</strong> uppermanagement, <strong>and</strong> its impact on <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong> outcomes. This is surpris<strong>in</strong>g given thefact that <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g numbers of mult<strong>in</strong>ationalcompanies are jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the rapidly develop<strong>in</strong>gAsian region <strong>and</strong> need to achieve mult<strong>in</strong>ationalecacy. There is no doubt that managers arearguably the most important human resource, whoplay a crucial role <strong>in</strong> the success of failure of anyorganization. A recent survey 8 jo<strong>in</strong>tly conducted byCCC 0748±8386/99/010053±12$17.50Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

54 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPERthe Far Eastern Economic Review <strong>and</strong> the AsianBus<strong>in</strong>ess News <strong>in</strong>terviewed executives of topcompanies <strong>in</strong> 10 Asian countries. Half of them(50.6 percent) conceded that they did not havesucient numbers of quali®ed managers to meetthe needs of organizations <strong>in</strong> their own countries.Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for more c<strong>and</strong>idate managers is certa<strong>in</strong>lyone way to close this dem<strong>and</strong>±supply gap; e€ectivemanagerial work <strong>stress</strong> reduction is another way todevelop <strong>and</strong> improve exist<strong>in</strong>g managerial humanresources. To develop suitable prophylacticmeasures, it is necessary to identify the sources<strong>and</strong> e€ects of <strong>job</strong>-related pressures.One of the very few studies <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>gmanagerial <strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong> non-western countries was <strong>in</strong>Hong Kong. Researchers 9 identi®ed six sources of<strong>stress</strong> among 1000 bus<strong>in</strong>ess executives: <strong>job</strong>assigned<strong>stress</strong>or, responsibility <strong>stress</strong>or, work/organizational climate <strong>stress</strong>or, career <strong>stress</strong>or,<strong>job</strong>±value con¯ict <strong>stress</strong>or <strong>and</strong> role ambiguity<strong>stress</strong>or. Each of them was related to respondents'self-reports of physical <strong>health</strong>, depend<strong>in</strong>g on theirgender, age <strong>and</strong> experience <strong>in</strong> a managerialposition. Although Hong Kong <strong>and</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> areboth <strong>in</strong>dustrialized Ch<strong>in</strong>ese societies, there mightstill be di€erences as well as similarities <strong>in</strong> managerial<strong>stress</strong>, due to di€erent historical/political/socialforces at work <strong>in</strong> two places. For <strong>in</strong>stance, HongKong has long been exposed to the western style ofmanagement, while <strong>Taiwan</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s paternalistic<strong>and</strong> autocratic <strong>in</strong> its organizational life. Therefore,it is worthwhile obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g data from <strong>Taiwan</strong>esemanagers to identify sources of managerial <strong>stress</strong>,which <strong>in</strong> turn, might a€ect managers' work morale,<strong>health</strong> <strong>and</strong> behavioural outcomes (such as smok<strong>in</strong>g,dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> absenteeism).It was with this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d that we adopted thewidely used diagnostic <strong>in</strong>strument the OccupationalStress Indicator (OSI) 10 to exam<strong>in</strong>e managerial<strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong>. The OSI is still a relatively newtest, but its reliability <strong>and</strong> validity <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Taiwan</strong>esework context have been established <strong>and</strong> are generallysatisfactory. 11,12 The <strong>in</strong>strument was orig<strong>in</strong>allydeveloped based on a comprehensive theoreticalframework which adopts a transactional view ofoccupational <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> emphasizes not only<strong>stress</strong>ors <strong>and</strong> outcomes, but also potential moderat<strong>in</strong>gvariables such as personality (Type A <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>ternal control) <strong>and</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies. Fig. 1presents a modi®ed theoretical framework for thisstudy.The primary purpose of this article was to presentresults of a study <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g the sources of <strong>stress</strong>,<strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong> among a heterogeneoussample of managers <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong>. As such, the presentstudy is perhaps the ®rst attempt <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>gmanagerial <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong> diverse organizations<strong>in</strong> a Ch<strong>in</strong>ese context. Another purpose ofthe study was to test the moderat<strong>in</strong>g e€ects ofpersonality <strong>and</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies.METHODSSubjectsA purposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g strategy was adopted,<strong>in</strong>tended to recruit a heterogeneous populationof <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers work<strong>in</strong>g for various typesof organizations (public vs private, <strong>in</strong>digenous vsmult<strong>in</strong>ational, large vs small) <strong>and</strong> ranked atdi€erent levels with<strong>in</strong> the organizations. We alsoattempted to cover major sections of the economy,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g manufactur<strong>in</strong>g, construction, bank<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> ®nanc<strong>in</strong>g, social <strong>and</strong> personal services, commerce<strong>and</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g. Participants were contacted:(1) through social organizations, such as theRotary Clubs (N ˆ 125), (2) through commercialassociations, such as the local Association ofImport <strong>and</strong> Export Dealers (N ˆ 125), (3) througheducational classes o€ered to managers by the localuniversities (N ˆ 52), (4) through personal socialnetworks (N ˆ 51). Questionnaires were distributedto potential respondents, yield<strong>in</strong>g a response rate of50 percent. After discard<strong>in</strong>g those questionnaireswith excessive miss<strong>in</strong>g data, the ®nal sample was347. Those managers were all based <strong>in</strong> central <strong>and</strong>southern <strong>Taiwan</strong>.MeasurementThe questionnaire battery <strong>in</strong>cluded:1. Demographic <strong>and</strong> work <strong>in</strong>formation: age,gender, education, marital status, occupation,tenure, rank, size of organization, personal<strong>health</strong> habits, absenteeism, etc.2. The Ch<strong>in</strong>ese OSI-2. Seven of the scales were:(a) Job <strong>satisfaction</strong> scale (12 items): two subscalesmeasur<strong>in</strong>g `<strong>satisfaction</strong> with the <strong>job</strong>itself' <strong>and</strong> `<strong>satisfaction</strong> with the organization'.(b) Stressors scale (40 items): eight subscalesmeasur<strong>in</strong>g `workload', `relationships',`home/work balance', `managerial role',`personal responsibility', `hassles', `recognition'<strong>and</strong> `organizational climate'.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

MANAGERIAL STRESS IN TAIWAN 55(c) Cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies scale (10 items): twosubscales measur<strong>in</strong>g `control' <strong>and</strong> `seek<strong>in</strong>gsupport'.(d) Physical <strong>health</strong> scale (6 items): two subscalesmeasur<strong>in</strong>g `calmness' <strong>and</strong> `energy'.Higher scores <strong>in</strong>dicated better physical<strong>health</strong>.(e) Mental <strong>health</strong> scale (12 items): three subscalesmeasur<strong>in</strong>g `contentment', `resilience'<strong>and</strong> `peace of m<strong>in</strong>d'. Higher scores <strong>in</strong>dicatedbetter mental <strong>health</strong>.(f) Type A behaviour scale (6 items): twosubscales measur<strong>in</strong>g `patience' <strong>and</strong> `drive'.(g) Control (4 items): measur<strong>in</strong>g perceived<strong>in</strong>¯uence at work.3. Work locus of control: Spector's 13 16-itemWork Locus of Control Scale (WLCS) wasused to measure the belief that work is underone's own control (<strong>in</strong>ternal) or under thecontrol of chance, fate or powerful others(external). In the present study, the WLCSwas scored <strong>in</strong> the direction of `<strong>in</strong>ternal' control.RESULTSThe ®nal sample of 347 managers was drawn from awide variety of organizations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g manufactur<strong>in</strong>g,construction <strong>and</strong> real estate, commerce<strong>and</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g, ®nanc<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>essservices, <strong>and</strong> social services. The contents oftheir work were also diverse, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g personnel<strong>and</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration, sales, production, research,®nanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> account<strong>in</strong>g, as well as medical care.There were roughly equal ratios of males <strong>and</strong>females (these ratios did not change signi®cantlywhen managers from the medical services, ma<strong>in</strong>lynurs<strong>in</strong>g ocers, were excluded). Overall, thissample was middle-aged, well-educated, marriedwith youngish children, long-serv<strong>in</strong>g, middlelevelmanagers, who worked <strong>in</strong> companies withfewer than 100 employees <strong>and</strong> for slightly longerhours (the statutory work<strong>in</strong>g hour <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> is44 hours per week). In terms of demographic<strong>and</strong> work-related characteristics, this sample wasquite representative of <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese middle-rangemanagers. Detailed sample characteristics are presented<strong>in</strong> Table 1.Reliability of scalesTable 2 presents the reliability of scales used <strong>in</strong>the study. One item (4) <strong>in</strong> the OSI Ð control scalewas deleted due to its low item±total correlation(ITC) coecient (r ˆ 0.06), to improve scaleparsimony <strong>and</strong> consistency. Overall, aggregatedscales yielded higher reliabilities than their subscales<strong>and</strong> <strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> scales were more reliablethan personality scales. With the exception of theType A scale, all of the scales were acceptablyreliable.<strong>Managerial</strong> <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>Among the eight categories of work <strong>stress</strong>orsmeasured by the OSI, <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managersreported `personal responsibility' as the most<strong>stress</strong>ful (item mean ˆ 4.33 on a six-po<strong>in</strong>t scale),followed by `workload' (item mean ˆ 4.05),`relationships (item mean ˆ 4.04), `organizationalclimate' (item mean ˆ 3.96), `recognition' (itemmean ˆ 3.95), `home/work balance' (itemmean ˆ 3.89), `hassles' (item mean ˆ 3.82) <strong>and</strong>®nally, `managerial role' (item mean ˆ 3.68). Theoverall level of work <strong>stress</strong> for managers wassigni®cantly higher than for the general workforce<strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> 11 (t ˆ 16.41, p 5 0.001).There were three broad <strong>in</strong>dices of work stra<strong>in</strong>:work morale (<strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions),<strong>health</strong> (physical <strong>and</strong> mental) <strong>and</strong> ®nally,behavioural outcomes (smok<strong>in</strong>g, dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, exercise,absenteeism). Overall, the <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managerswere `satis®ed' with their <strong>job</strong>s (item mean ˆ 3.95on a six-po<strong>in</strong>t scale); furthermore, this level of <strong>job</strong><strong>satisfaction</strong> was signi®cantly higher than the generalworkforce <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> 11 (t ˆ 6.04, p 5 0.001). Ascan be seen <strong>in</strong> Table 1, most managers (40.2percent) only `sometimes' considered quitt<strong>in</strong>g thepresent <strong>job</strong>, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g no strong turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions.Both avowed mental <strong>and</strong> physical <strong>health</strong> werenear the midpo<strong>in</strong>t tilt<strong>in</strong>g towards the better ends onsix-po<strong>in</strong>t scales (item means ˆ 3.97 <strong>and</strong> 4.19).However, these levels were signi®cantly poorerthan the general workforce <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> 11 (t ˆ 3.40<strong>and</strong> 3.61, p 5 0.001). As for behavioural outcomes,results were more encourag<strong>in</strong>g: by far the majorityof managers did not smoke or dr<strong>in</strong>k, managed an`ideal' exercise programme <strong>and</strong> had very few dayso€ due to personal sickness (Table 1).When demographic di€erentials were exam<strong>in</strong>ed,a series of chi-square tests demonstrated that therewere signi®cantly more male managers <strong>in</strong> the top<strong>and</strong> senior ranks than female managers; the trendwas reversed <strong>in</strong> the middle <strong>and</strong> junior positions (chisquareˆ 12.90, df ˆ 3, p 5 0.01). There were moremale managers who smoked or drank than femalesCopyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

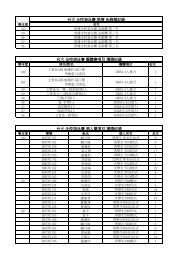

56 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPERTable 1 Ð Sample characteristicsVariables N % Mean & SDAge 320 37.87 5.69 (21±76)GenderMale 191 55.0%Female 151 43.5%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 5 1.4%EducationPrimary 1 0.3% (yr of education)Junior 2 0.6% 15.60 1.90Senior 52 15%College 242 69.7%Postgraduate 50 14.4%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 0Marital statusS<strong>in</strong>gle 86 24.8%Married 254 73.2%Separated, divorced, widowed 5 1.5%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 2 0.6%Age of youngest child (for those with children) 215 9.27 6.92 (0.5±36)Tenure (yr) 328 10.22 7.91 (0.25±40)RankTop 60 17.3%Senior 39 11.2%Middle 86 24.8%Junior 159 45.8%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 4 0.9%Work contentSales 68 19.6%Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative 34 9.8%Production 54 15.6%F<strong>in</strong>ance 39 11.2%Medical 47 13.5%Others 47 13.5%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 10 16.7%OccupationManufactur<strong>in</strong>g 62 17.9%Commerce 64 18.4%F<strong>in</strong>ance 41 11.8%Industrial service 48 13.8%Social service 103 29.7%Others 19 5.5%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 10 2.9%No. of employees5100 138 39.8%100±500 73 21.0%500±1000 35 10.1%1000±5000 76 21.9%45000 21 6.1%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 4 1.2%Table 1. Cont<strong>in</strong>ued over page.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

MANAGERIAL STRESS IN TAIWAN 57Table 1 Ð Cont<strong>in</strong>uedVariables N % Mean & SDWork<strong>in</strong>g hours (per week) 46.36 12.89 (5±120)Turnover <strong>in</strong>tentionNever 70 20.2%Rarely 96 27.7%Sometimes 140 40.3%Quite often 26 7.5%Extremely often 9 2.6%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 6 1.7%ExerciseAlways 26 7.5%Usually 66 19%Sometimes 70 20.2%Occasionally 125 36%Never 56 16.1%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 4 1.2%Smok<strong>in</strong>gYes 55 15.9%No 287 82.7%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 5 1.4%Dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gYes 88 25.4%No 253 72.9%Miss<strong>in</strong>g 6 1.7%Sick leaveNever 303 87.3%Yes 44 12.7%Sick days 1.98 1.59 (1±10)Note: Ranges are shown <strong>in</strong> brackets.(chi-square ˆ 47.30 <strong>and</strong> 65.20, df ˆ 1, p 5 0.001).A number of t-tests also revealed that femalemanagers reported more `managerial role' <strong>stress</strong>than their male counterparts (t ˆ 2.49, p 5 0.05).Another series of t-tests was conducted to see ifthere were any di€erences on <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong> atdi€erent levels of management. Top <strong>and</strong> seniormanagers were pooled to contrast with pooledmiddle <strong>and</strong> junior managers. Results showed thatcompared with the lower-rank managers, thehigher-rank managers were more satis®ed withtheir <strong>job</strong>s (t ˆ 3.18, p 5 0.01) <strong>and</strong> reported bettermental <strong>health</strong> (t ˆ 2.36, p 5 0.05).ModeratorsIn the present study, three potential moderatorswere considered: Type A behaviour pattern,<strong>in</strong>ternal locus of control <strong>and</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g e€orts. Overall,the <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers were not particularlyType A, as <strong>in</strong>dicated by the item mean of 3.49 on asix-po<strong>in</strong>t scale. However, this level was alreadysigni®cantly higher than the general workforce <strong>in</strong><strong>Taiwan</strong> (t ˆ 14.10, p 5 0.001). Similarly, they werenot particularly <strong>in</strong>ternally controlled either, as<strong>in</strong>dicated by the item mean of 3.90 on a six-po<strong>in</strong>twork locus of control scale; they even scoredsigni®cantly lower than the general workforce(t ˆ 26.36, p 5 0.001), as measured by theOSI Ð control scale.Managers, however, reported relatively highlevels of cop<strong>in</strong>g e€orts, signi®cantly higher thanthe general workforce (t ˆ 11.71, p 5 0.001). Interest<strong>in</strong>gly,`control' (item mean ˆ 4.48 on a six-po<strong>in</strong>tscale) seemed more often adopted than `seek<strong>in</strong>gsupport' (item mean ˆ 4.17).Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

58 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPERTable 2 Ð Reliability of all scalesScales Mean SD Item no. AlphaJob <strong>satisfaction</strong> 47.42 9.24 12 0.92Job itself 24.68 4.94 6 0.88Organization 22.77 5.10 6 0.88Mental <strong>health</strong> 47.62 8.47 12 0.81Contentment 19.41 4.63 5 0.74Resilience 17.61 3.04 4 0.64Peace of m<strong>in</strong>d 10.55 2.94 3 0.57Physical <strong>health</strong> 25.14 5.49 6 0.82Calmness 13.38 3.04 3 0.77Energy 11.77 3.10 3 0.71Type A behaviour 20.94 3.05 6 0.46Impatience 10.79 5.11 3 0.62Drive 10.13 2.26 3 0.69OSI Ð control 8.95 2.10 3 0.72WLCS (Work Locus of Control) 62.33 5.78 16 0.73Cop<strong>in</strong>g 43.56 5.15 10 0.76Control 26.86 3.52 6 0.79Seek<strong>in</strong>g support 16.68 2.61 4 0.51Stressors 159.00 24.69 40 0.94Workload 24.30 4.77 6 0.78Relationships 32.29 6.10 8 0.86Home/work balance 23.35 4.69 6 0.74<strong>Managerial</strong> role 14.72 3.04 4 0.54Personal responsibility 17.30 3.40 4 0.74Hassles 15.29 2.95 4 0.61Recognition 15.78 3.18 4 0.75Organizational climate 15.83 3.10 4 0.69Stress±moderators±stra<strong>in</strong> relationshipsTable 3 presents the relationships amongdemographics, work experiences, <strong>stress</strong>, Type A,<strong>in</strong>ternal control, cop<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>, mental<strong>and</strong> physical <strong>health</strong>, smok<strong>in</strong>g, dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, exercise,absenteeism <strong>and</strong> turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions. Regard<strong>in</strong>g<strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> relationships, work <strong>stress</strong> positivelycorrelated with turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions <strong>and</strong> negativelycorrelated with <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>, mental <strong>health</strong><strong>and</strong> physical <strong>health</strong>. Regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>stress</strong>±moderatorsrelationships, control was the only <strong>and</strong> negativecorrelate of work <strong>stress</strong>. Regard<strong>in</strong>g moderators±stra<strong>in</strong> relationships, control positively correlatedwith <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> mental <strong>and</strong> physical<strong>health</strong>, <strong>and</strong> negatively correlated with turnover<strong>in</strong>tentions, absenteeism <strong>and</strong> smok<strong>in</strong>g. Cop<strong>in</strong>g, onthe other h<strong>and</strong>, positively correlated with <strong>job</strong><strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> mental <strong>health</strong>.A series of further correlation analyses wascarried out to exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>tercorrelations amongall the OSI scales, their subscales <strong>and</strong> the WLCS.Results are summarized below, while more detailsare available from the authors. First, signi®cant<strong>in</strong>tercorrelations with<strong>in</strong> a particular constructranged from 0.17 (OSI Ð control/WLCS) to 0.72(`relationship <strong>stress</strong>'/`workload <strong>stress</strong>'). The onlynon-signi®cant correlation was between the twoType A subscales (`patience'/`drive'). Secondly,`resilience' was the worst mental <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicator,which produced the fewest signi®cant correlationswith the <strong>stress</strong> measures. Similarly, `calmness' wasthe worst physical <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicator, which producedthe fewest signi®cant correlations with the<strong>stress</strong> measures. Thirdly, `drive' as a Type Acharacteristic was not associated with any of thestra<strong>in</strong> measures. Fourthly, OSI Ð control <strong>and</strong> theWLCS produced comparable results perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tothe stra<strong>in</strong> measures. F<strong>in</strong>ally, `seek<strong>in</strong>g support' as acop<strong>in</strong>g strategy did not correlate with the stra<strong>in</strong>measures.Predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>job</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>In order to test statistically the proposedrelationships among demographics, work experiences,work <strong>stress</strong>, moderators <strong>and</strong> <strong>job</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>, asCopyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

MANAGERIAL STRESS IN TAIWAN 59Table 3 Ð Correlations among demographics, work experiences, <strong>health</strong> habits, absenteeism, turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions <strong>and</strong> other aggregated scales1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 181. Sex 12. Age 0.24*** 13. Edu. 0.02 0.10 14. Mar. 0.21*** 0.42*** 0.01 15. Tenure 0.01 0.70*** 0.07 0.28*** 16. Rank 0.17*** 0.37*** 0.05 0.25*** 0.20*** 17. Smok<strong>in</strong>g 0.38*** 0.10 0.16** 0.08 0.11 0.06 18. Dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 0.44*** 0.06 0.01 0.06 0.04 0.19*** 0.44*** 19. Exercise 0.19*** 0.16** 0.04 0.03 0.16** 0.11* 0.06 0.07 110. Leave 0.10 0.03 0.07 0.08 0.10 0.07 0.09 0.07 0.03 111. Quit 0.06 0.18** 0.06 0.24*** 0.18*** 0.29*** 0.03 0.04 0.03 0.09 112. JS 0.00 0.12* 0.10 0.17** 0.05 0.17** 0.03 0.07 0.11 0.07 0.34*** 113. MH 0.04 0.24*** 0.02 0.18*** 0.19*** 0.13* 0.04 0.04 0.09 0.15** 0.29*** 0.30*** 114. PH 0.04 0.26*** 0.01 0.19*** 0.17** 0.10 0.19*** 0.06 0.07 0.21*** 0.18*** 0.24*** 0.59*** 115. Stress 0.07 0.05 0.08 0.03 0.01 0.11 0.01 0.05 0 0.01 0.12* 0.23*** 0.33*** 0.18*** 116. Type A 0.15** 0.01 0.06 0.12* 0.02 0.09 0.03 0.04 0.02 0.06 0 0.07 0.05 0.12 0.03 117. Control 0.03 0.09 0.13* 0.08 0.14* 0.15** 0.03 0.08 0.02 0.08 0.17*** 0.30*** 0.25*** 0.17*** 0.25*** 0.04 118. WLCS 0.09 0.07 0.10 0.07 0.01 0.18*** 0.11* 0.07 0.01 0.19*** 0.16** 0.26*** 0.24*** 0.17** 0.02 0.03 0.17** 119. Cop<strong>in</strong>g 0.04 0.11 0.15** 0.06 0.08 0.14* 0.02 0.06 0.03 0.02 0.10 0.15** 0.13* 0.06 0.08 0.03 0.02 0.14*Sex, 1 ˆ M, 2 ˆ F; Edu., years of education; Mar., 1 ˆ s<strong>in</strong>gle, 2 ˆ married; Rank, 1 ˆ high-level, 2 ˆ low-level; Smok<strong>in</strong>g, 1 ˆ smokers, 2 ˆ non-smokers; Dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g,1 ˆ dr<strong>in</strong>kers, 2 ˆ non-dr<strong>in</strong>kers; Leave, days of sick leave; JS, <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>; MH, mental <strong>health</strong>; PH, physical <strong>health</strong>.*p 4 0.05; **p 4 0.01; ***p 4 0.001.depicted <strong>in</strong> Fig. 1, a series of hierarchicalregression analyses was conducted to predict<strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>, mental <strong>health</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical<strong>health</strong> separately. Signi®cant zero-order Pearson'scorrelation coecients between pairs of <strong>in</strong>dependent<strong>and</strong> dependent variables, as presented <strong>in</strong>Table 3, formed the <strong>in</strong>itial criterion for the<strong>in</strong>clusion of potential predictors. In each case,demographics were entered ®rst <strong>in</strong>to the equation,followed by work-related experiences at the secondstep, to statistically control their <strong>in</strong>¯uences. At thethird step, work <strong>stress</strong> was entered <strong>in</strong>to theequation, followed by moderators at the fourthstep. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the <strong>in</strong>teractions between work <strong>stress</strong><strong>and</strong> moderators were <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the regression.In predict<strong>in</strong>g physical <strong>health</strong>, as smok<strong>in</strong>g wassigni®cantly correlated with global physical <strong>health</strong>,it was also <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the equation to partial outits potential e€ects on the dependent variable. Inan attempt to achieve model parsimony, those<strong>in</strong>itially <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>dependent variables whichmade no signi®cant contribution to the R-squarewere deleted <strong>and</strong> the analysis repeated. Table 4presents the ®nal results of the three regressionanalyses.When predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>, four out of®ve layers of <strong>in</strong>dependent variables were presented<strong>in</strong> the ®nal equation, <strong>and</strong> a total of 19 per cent ofthe variance <strong>in</strong> the dependent variables wasaccounted for by the ®ve predictors. Amongthem, <strong>in</strong>ternal control demonstrated the strongest(positive) <strong>in</strong>¯uence on <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>, whereaswork <strong>stress</strong> demonstrated the strongest (negative)<strong>in</strong>¯uence. None of the <strong>in</strong>teraction terms reachedstatistical signi®cance. In other words, there wasno evidence of the bu€er<strong>in</strong>g e€ects of <strong>in</strong>ternalcontrol as a moderator of the <strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong>relationship.When predict<strong>in</strong>g mental <strong>health</strong>, four predictorsrema<strong>in</strong>ed signi®cant <strong>in</strong> the ®nal equation, account<strong>in</strong>gfor a total of 23 percent of the variance <strong>in</strong>mental <strong>health</strong>. Age <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal control werepositively related to mental <strong>health</strong>, whereas work<strong>stress</strong> was negatively related to it. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, the<strong>in</strong>teraction term between work <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternalcontrol reta<strong>in</strong>ed its statistical signi®cance, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>ga vulnerability e€ect of <strong>in</strong>ternal control on the<strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> relationship.When predict<strong>in</strong>g physical <strong>health</strong>, four predictorsrema<strong>in</strong>ed signi®cant <strong>in</strong> the ®nal equation,account<strong>in</strong>g for a total of 14 percent of the variance<strong>in</strong> physical <strong>health</strong>. Age <strong>and</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g marriedwere positively related to mental <strong>health</strong>, whereasCopyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

60 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPERFig. 1. Ð Relationships among work <strong>stress</strong>ors, moderators <strong>and</strong> <strong>job</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>Table 4 Ð Predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>job</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>Variables b R 2 R 2 D F ConstantJob <strong>satisfaction</strong>‡ Marital status 0.14* 0.03 0.03**‡ Rank 0.04 0.05 0.02*‡ Stress 0.16** 0.09 0.04***‡ WLCS 0.20*** 0.19 0.10***OSI Ð Control 0.22***Total 0.19 12.23*** 23.46Mental <strong>health</strong>‡ Age 0.21*** 0.05 0.05***‡ Stress 0.13*** 0.16 0.11***‡ WLCS 0.33*** 0.20 0.04***‡ Stress WLCS 1.14*** 0.23 0.03**Total 13.65*** 35.88Physical <strong>health</strong>‡ Age 0.19** 0.07 0.07***Marital status 0.12*‡ Smok<strong>in</strong>g 0.17* 0.09 0.03**‡ Type A Ð impatience 0.22*** 0.14 0.05***Total 12.50*** 19.28*p 4 0.05; **p 4 0.01; ***p 4 0.001.smok<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the `impatient' characteristic of theType A behaviour pattern were negatively relatedto it. The <strong>in</strong>teraction between impatience <strong>and</strong> work<strong>stress</strong> did not reach statistical signi®cance, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>gno evidence of Type A as a moderator for the<strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> relationship.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

MANAGERIAL STRESS IN TAIWAN 61DISCUSSIONThe impact of managerial <strong>stress</strong>Be<strong>in</strong>g one of the very few concerted e€orts<strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g managerial <strong>stress</strong> across the barriersof a s<strong>in</strong>gle organization, a s<strong>in</strong>gle occupation or asection of the national economy, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> a nonwesterncountry, this study generated valuableevidence of the impact of managerial <strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong> arapidly <strong>in</strong>dustrializ<strong>in</strong>g society. Among the topthree work <strong>stress</strong>ors reported by the <strong>Taiwan</strong>esemanagers, `personal responsibility' <strong>and</strong> `relationships'may be particularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> relevant<strong>in</strong> a Ch<strong>in</strong>ese culture. In Hofstede's 14 sem<strong>in</strong>alwork on the cross-cultural comparison of workrelatedvalues, <strong>Taiwan</strong> was identi®ed as moderate<strong>in</strong> power distance (ranked 29/30 among 53countries), low <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualism (ranked 44among 53 countries), <strong>and</strong> moderate <strong>in</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>tyavoidance (ranked 26 among 53 countries).Corroborat<strong>in</strong>g this general description of the<strong>Taiwan</strong>ese culture, managers would be di<strong>stress</strong>ed<strong>in</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g personal responsibilities, which often<strong>in</strong>volve exercis<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>and</strong> tolerat<strong>in</strong>g uncerta<strong>in</strong>ties;<strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers would also be ratherconcerned about the <strong>in</strong>terpersonal relationships atwork. The empirical evidence seemed quite consistentwith this theoretical reason<strong>in</strong>g. As noted byother researchers, 15,16 Ch<strong>in</strong>ese workers, especiallymanagers, value guangxi, the aliative relationshipbetween superiors <strong>and</strong> coworkers, which is acharacteristic of the large power distance culture.Although empirical evidence was <strong>in</strong>conclusive 16<strong>and</strong> not particularly strong, it did po<strong>in</strong>t to thevalue of conduct<strong>in</strong>g more cross-cultural comparativestudies to map out universality as wellas speci®city <strong>in</strong> the work <strong>stress</strong> experiences <strong>in</strong>di€erent societies.On the quantitative aspects of the experience ofmanagerial <strong>stress</strong>, <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers perceivedmore <strong>stress</strong> than the general workforce <strong>in</strong> thecountry <strong>and</strong> were also more <strong>stress</strong>ed than managers<strong>in</strong> Hong Kong 17 (t ˆ 3.78, p 5 0.001), the UK <strong>and</strong>Germany 18 (t ˆ 13.10 <strong>and</strong> t ˆ 8.69, p 5 0.001).This level of work <strong>stress</strong> was related to <strong>job</strong><strong>satisfaction</strong>, mental <strong>health</strong>, physical <strong>health</strong> <strong>and</strong>turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions (Table 3). Furthermore, work<strong>stress</strong> was a powerful predictor of <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong>(account<strong>in</strong>g for 4 percent of the variance) <strong>and</strong>mental <strong>health</strong> (account<strong>in</strong>g for 11 percent of thevariance). These results are consistent withprevious ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs. 18,19 The problems of smok<strong>in</strong>g,dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, lack of exercise <strong>and</strong> absenteeism were notsevere among this sample of managers (Table 1).While the behavioural symptoms of <strong>stress</strong> were notparticularly evident, due to the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese culturalcensorship of excessive smok<strong>in</strong>g or dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, theself-reported <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators were rather clear:<strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers disclosed worse mental <strong>and</strong>physical <strong>health</strong> than the general workforce <strong>in</strong> thecountry. Although the comparison methodadopted may warrant some methodological concernsÐ simply compar<strong>in</strong>g the work <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>health</strong> of managers <strong>in</strong> this study with other samples<strong>in</strong> the literature Ð the cross-sectional data suggestthat <strong>Taiwan</strong> managers may be under <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> riskof ill-<strong>health</strong>.In recent years, some research has demonstratedthat female managers are under higher<strong>stress</strong> than their male counterparts, 20±22 whereasother research yielded <strong>in</strong>conclusive results. 23In this study, a t-test revealed that <strong>Taiwan</strong>esefemale managers did report more <strong>stress</strong> relatedto the `managerial role' than their male counterparts(mean ˆ 15.20 vs 14.37, t ˆ 2.49, p 5 0.05),thus partially corroborat<strong>in</strong>g the previous studies.This seem<strong>in</strong>gly consistent pattern of femaledisadvantage <strong>in</strong> managerial positions is very<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g as it provides <strong>in</strong>direct support forthe role con¯ict thesis, which states that thesocially approved characteristics of fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ity(such as nurturance <strong>and</strong> submission) may oftencome <strong>in</strong>to con¯ict with the requirements of a`mascul<strong>in</strong>e' managerial role (such as toughness<strong>and</strong> assertion). The prevail<strong>in</strong>g hostility aga<strong>in</strong>stfemales, the lack of female role models, unsupportivesuperiors (usually males), long-establishedbus<strong>in</strong>ess practices with sexual overtures, <strong>and</strong>the dilemma between career commitment <strong>and</strong>family duties may all compound to produce thehigh level of work <strong>stress</strong> encountered by femalemanagers <strong>in</strong> a paternalistic Ch<strong>in</strong>ese societysuch as <strong>Taiwan</strong>. 24,25 Hopefully, these ®nd<strong>in</strong>gswill serve to raise awareness of the unduly highwork <strong>stress</strong> endured by these Ch<strong>in</strong>ese femalemanagers <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> turn, facilitate steps to reduceits detrimental e€ects on <strong>health</strong> <strong>and</strong> workmorale.Structural relationships among work <strong>stress</strong>,moderators <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>The structural relationships depicted <strong>in</strong> Fig. 1were largely borne out by correlational <strong>and</strong>regression analyses. More speci®cally, most of theCopyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

62 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPER<strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> relationships were signi®cant, exceptthose <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>health</strong> habits. Tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>toaccount the previously mentioned characteristics ofthe Ch<strong>in</strong>ese culture, these results corroborateprevious ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs. 20±22 Furthermore, the relationshipbetween perceived work <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> turnover<strong>in</strong>tentions warrants attention from managerialpractitioners. As mentioned earlier, there exists asubstantial shortage of adequately tra<strong>in</strong>ed managers<strong>in</strong> the fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g Eastern Asian countries,<strong>and</strong> the turnover rate with<strong>in</strong> the managerialcommunity has rema<strong>in</strong>ed rather high. Reduc<strong>in</strong>gwork <strong>stress</strong> may be a promis<strong>in</strong>g approach toconta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the high turnover rate, which, <strong>in</strong> turn,will save considerable resources for the organizations.In this study, there was no signi®cant relationshipfound between <strong>job</strong> <strong>stress</strong> or <strong>job</strong> stra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong>the global Type A behaviour pattern, nor withits `drive' subscale (hard-driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> competitiveness).However, the `impatience' facet (rushedbehaviour <strong>and</strong> abrupt manner) was signi®cantlycorrelated with both mental <strong>and</strong> physical <strong>health</strong>(r ˆ0.22, p 5 0.001 <strong>and</strong> r ˆ0.14, p 5 0.01respectively). `Impatience' was even a signi®cantpredictor of physical <strong>health</strong> (Table 4), expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gabout 5 percent of the variance. These resultsare consistent with the exist<strong>in</strong>g evidence <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>gthat the speed±impatience component, <strong>and</strong> notthe competitive drive, is associated with psychologicaldi<strong>stress</strong>. 26 These ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs also underl<strong>in</strong>ethe importance of treat<strong>in</strong>g Type A behaviour as amultidimensional construct, with some of itscharacteristics relat<strong>in</strong>g directly to work stra<strong>in</strong>without moderat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> nexus.Some researchers even claim that certa<strong>in</strong> speci®ccomponents of the Type A behaviour pattern mayeven be bene®cial to psychological well-be<strong>in</strong>gamong executives. 18 Furthermore, the Type Abehaviour pattern may possess desirable characteristics<strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong>y attitudes, 27,28 so that Type Apersons are perceived as better performers <strong>and</strong>are more likely to be promoted to managerialpositions. This may partially expla<strong>in</strong> the fact thatthis sample of <strong>Taiwan</strong>ese managers was moreType-Alike than their counterparts <strong>in</strong> the generalworkforce, yet signi®cantly less Type A-likecompared to the British or German managers(t ˆ5.23 <strong>and</strong> t ˆ4.29, p 5 0.001). 18 However,caution must be exercised when generaliz<strong>in</strong>g acrossmeasures as the components of Type A behaviourare not themselves highly <strong>in</strong>terrelated (ref. 26 <strong>and</strong>the present study).Internal control was associated with lower levelsof personal work <strong>stress</strong>. It was also related to awide range of stra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators, both behavioural(smok<strong>in</strong>g, absenteeism <strong>and</strong> turnover <strong>in</strong>tentions)<strong>and</strong> psychological (<strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong>). Itpresented the only signi®cant moderat<strong>in</strong>g e€ect onthe <strong>stress</strong>±stra<strong>in</strong> nexus (Table 4). However, theseresults defy a simple proposal of the underly<strong>in</strong>gmechanism. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, the ma<strong>in</strong> e€ects of<strong>in</strong>ternal control on reduced <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong> wereconsistent with previous research <strong>in</strong> both organizationalcontexts 3,7,18,29 <strong>and</strong> were congruent with thecharacteristics of <strong>in</strong>ternal control as feel<strong>in</strong>g con®dent<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> control of what happens to oneself, <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> the potency of one's decisions <strong>and</strong> action forpersonal outcomes. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, themoderat<strong>in</strong>g e€ects of control have been <strong>in</strong>consistent<strong>in</strong> the work context. 3,18 The present study,unexpectedly, found a vulnerability e€ect of<strong>in</strong>ternal control on the <strong>stress</strong>±mental <strong>health</strong>nexus. Explanations may be found with<strong>in</strong> thecharacteristics of the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese culture perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gto organizational life. In fact, <strong>in</strong> most <strong>Taiwan</strong>eseorganizations traditional authoritarian rather th<strong>and</strong>emocratic, paternalistic rather than egalitarian,culture still prevails. Workers, blue-collar, whitecollar<strong>and</strong> middle-level managers alike, havevirtually no control <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>¯uence with regard tothe organizational processes: decisions are made atthe top, implemented with top-down communication,<strong>and</strong> only very recently have some companiesopened channels for workers to expresscompla<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>and</strong> discontent. Also <strong>in</strong> accordancewith the traditional Ch<strong>in</strong>ese ethic of respect forthe elder, <strong>job</strong> promotion is aga<strong>in</strong> unrelated toperformance, but rather to seniority with<strong>in</strong> theorganization. If noth<strong>in</strong>g drastic happens (whenwork <strong>stress</strong> is low), <strong>in</strong>ternal control may serve tosafeguard one's personal con®dence <strong>and</strong> psychologicalwell-be<strong>in</strong>g; however, if work <strong>stress</strong> is high,preserv<strong>in</strong>g one's beliefs <strong>in</strong> personal control <strong>and</strong>actually striv<strong>in</strong>g for it, as persons of <strong>in</strong>ternalcontrol habitually do, may be counterproductive<strong>in</strong> a paternalistic <strong>and</strong> autocratic work scene likethat of <strong>Taiwan</strong>. This emic <strong>in</strong>terpretation is consistentwith other empirical evidence collected <strong>in</strong><strong>Taiwan</strong>ese organizations. 12,25 Once aga<strong>in</strong>, theimportance <strong>and</strong> necessity of conduct<strong>in</strong>g crossculturalcomparisons on occupational <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong>stra<strong>in</strong> to qualify the generalizability of westerntheories <strong>and</strong> ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> to discover new patterns<strong>and</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>gs from a di€erent culture's vantagepo<strong>in</strong>t are highlighted.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

MANAGERIAL STRESS IN TAIWAN 63Cross-cultural reliability <strong>and</strong> validity of the OSI-2As far as the use of OSI-2 (a brief version used <strong>in</strong>the present study) <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> is concerned, the<strong>in</strong>ternal consistency of its various scales wasacceptably high, except the global Type A behaviourpattern (Table 2). This pattern of results isconsistent with previous ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs us<strong>in</strong>g a longerversion of the OSI <strong>in</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong> 3,7 <strong>and</strong> HongKong. 16,17 Furthermore, the pattern of structuralrelationships among the OSI scales is rather similaracross <strong>Taiwan</strong>, Hong Kong, Brita<strong>in</strong> 10 <strong>and</strong>Germany. 18 In the present study, the work <strong>stress</strong>scale demonstrated good predictive validity(Table 4) <strong>and</strong> criterion validity (Table 3), whereasthe control scale showed good convergent validitywith another established work locus of controlscale (Table 3). The available OSI data for frontl<strong>in</strong>eemployees accord with the ®nd<strong>in</strong>gs of managerial®gures reported <strong>in</strong> the literature. 3,7,10,16 Overall,these results <strong>in</strong>dicate that the OSI-2 is a promis<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> relatively brief <strong>in</strong>strument <strong>in</strong> measur<strong>in</strong>g work<strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> its related factors <strong>in</strong> a Ch<strong>in</strong>ese organizationalcontext.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTThis research was supported by a grant from theCAPCO Cultural <strong>and</strong> Educational Foundation,<strong>Taiwan</strong>.REFERENCES1. ILO. World Labour Report. ILO, New York, 1993.2. Matteson, M. T. <strong>and</strong> Ivancevich, J. M. Controll<strong>in</strong>gWork Stress. Jossey-Bass, London, 1987.3. Lu, L., Chen, Y. C. <strong>and</strong> Hsu, C. H. OccupationalStress <strong>and</strong> its Correlates. IOSH, Taipei, 1994.4. Chang, F. M. C. Psychopathology among Ch<strong>in</strong>esepeople. In: The Psychology of the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese People.Bond, M. H. (Ed.) Oxford University Press,Hong Kong, 1986.5. Chu, L. L. The social <strong>in</strong>teraction among Ch<strong>in</strong>esepeople: The problem of face. In: The Psychology ofthe Ch<strong>in</strong>ese People. Yang, K. S. (Ed.) LarureateBooks, Taipei, 1988.6. Kleiman, A. <strong>and</strong> Kleiman, J. Face, favour <strong>and</strong>families: The social course of mental <strong>health</strong> problems<strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>and</strong> American societies. Ch<strong>in</strong>eseJ. Ment. Health 1993; 6(1): 37±47.7. Lu, L., Shiau, C. <strong>and</strong> Cooper, C. L. Occupational<strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical nurses. Counsel. Psychol. Quart.1997; 10(1): 39±50.8. Granitsas, A. Wanted 3 million managers for Asia.Learn<strong>in</strong>g Devel. 1997; 500: 68±76.9. S<strong>in</strong>, L. <strong>and</strong> Cheng, D. Occupational <strong>stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong>among bus<strong>in</strong>ess executives: An exploratory study <strong>in</strong>an Oriental culture. Int. J. Manage. 1995; 12(1):14±25.10. Cooper, C. L., Sloan, S. J. <strong>and</strong> Williams, S. OccupationalStress Indicator Management Guide NFER-Nelson, W<strong>in</strong>dsor, 1988.11. Lu, L., Cooper, C. L., Chen, Y. C., Hsu, C. H., Li,C. H., Wu, H. L. <strong>and</strong> Shih, J. B. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese version ofthe OSI: A study of reliability <strong>and</strong> factor structures.Stress Med. 1995; 11: 149±155.12. Lu, L., Cooper, C. L., Chen, Y. C., Hsu, C. H., Wu,H. L., Shih, J. B. <strong>and</strong> Li, C. H. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese version of theOSI: A validation study. Work Stress 1997; 11(1):79±86.13. Spector, P. E. Development of the Work Locusof Control Scale. J. Occupat. Psychol. 1988; 61:335±340.14. Hofstede, G. Cultures <strong>and</strong> Organizations: Software ofthe M<strong>in</strong>d. McGraw-Hill, London, 1991.15. Chow, I. H. S. Occupational commitment <strong>and</strong>career development of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese managers <strong>in</strong>Hong Kong <strong>and</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong>. Int. J. Career Manage.1994; 6(4): 3±9.16. Siu, O. L., Cooper, C. L. <strong>and</strong> Donald, I. Occupational<strong>stress</strong>, <strong>job</strong> <strong>satisfaction</strong> <strong>and</strong> mental <strong>health</strong>among employees of an acquired TV company <strong>in</strong>Hong Kong. Stress Med. 1997; 13: 99±107.17. Siu, O. L., Lu, L. <strong>and</strong> Cooper, C. L. <strong>Managerial</strong><strong>stress</strong> <strong>in</strong> Hong Kong <strong>and</strong> <strong>Taiwan</strong>: A comparativestudy. Unpublished manuscript, 1997.18. Kirkcaldy, B. D. <strong>and</strong> Cooper, C. L. Cross-culturaldi€erences <strong>in</strong> occupational <strong>stress</strong> among British<strong>and</strong> German managers. Work Stress 1992; 6(2):177±190.19. Cooper, C. L. Executive <strong>stress</strong>: A ten countrycomparison. Human Resource Manage. 23: 395±407.20. Davidson, M. <strong>and</strong> Cooper, C. L. Stress <strong>and</strong> theWoman Manager. Mart<strong>in</strong> Robertson, Oxford, 1983.21. Davidson, M. <strong>and</strong> Cooper, C. L. The WomanManager. Chapman, London, 1992.22. Langan-Fox, J. <strong>and</strong> Poole, M. E. Occupational <strong>stress</strong><strong>in</strong> Australian bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>and</strong> professional women.Stress Med. 1995; 11: 113±122.23. Beatty, C. A. The <strong>stress</strong> of managerial <strong>and</strong> professionalwomen: Is the price too high? J. Org.Behav. 1996; 17: 23±251.24. L<strong>in</strong>, D. M. <strong>and</strong> Liu, S. M. The psychologicaladjustment of female managers. The Taipei Conferenceof Mental Health, Taipei, <strong>Taiwan</strong>, 1996.25. Lu, L. The process of work <strong>stress</strong>: A dialoguebetween theory <strong>and</strong> research. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese J. Ment.Health 10: 39±51.26. Cramer, D. Type A behaviour pattern, extraversion,neuroticism <strong>and</strong> psychological di<strong>stress</strong>. Brit. J. Med.Psychol. 1991; 64: 73±83.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)

64 L. LU, H-J. TSENG AND C. L. COOPER27. Ivancevich, J. M. <strong>and</strong> Matteson, M. T. Type Abehaviour <strong>and</strong> the <strong>health</strong>y <strong>in</strong>dividual. Brit. J. Med.Psychol. 1988; 61: 37±56.28. Knobloch, J. Perception of Cardiovascular Processes<strong>and</strong> Health. Pro®l, Munich, 1990.29. Spector, P. E. Behaviour <strong>in</strong> organizations as afunction of employees locus of control. Psychol.Bull. 1982; 91: 482±497.Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Stress med. 15, 53±64 (1999)