2010 and 2011 - Census Bureau

2010 and 2011 - Census Bureau

2010 and 2011 - Census Bureau

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

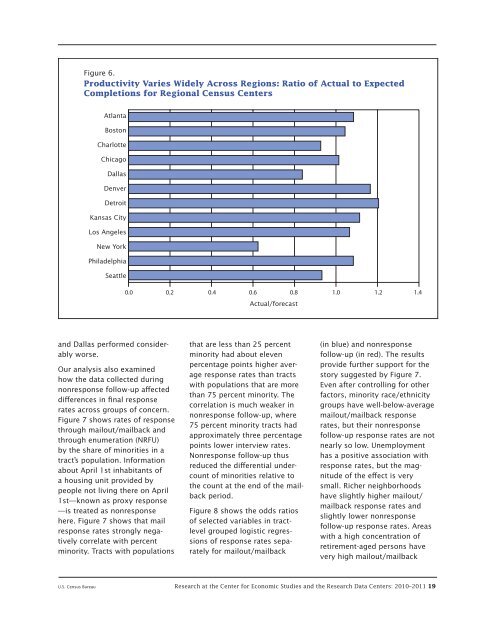

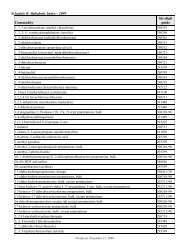

Figure 6.<br />

Productivity Varies Widely Across Regions: Ratio of Actual to Expected<br />

Completions for Regional <strong>Census</strong> Centers<br />

Atlanta<br />

Boston<br />

Charlotte<br />

Chicago<br />

Dallas<br />

Denver<br />

Detroit<br />

Kansas City<br />

Los Angeles<br />

New York<br />

Philadelphia<br />

Seattle<br />

<strong>and</strong> Dallas performed considerably<br />

worse.<br />

Our analysis also examined<br />

how the data collected during<br />

nonresponse follow-up affected<br />

differences in final response<br />

rates across groups of concern.<br />

Figure 7 shows rates of response<br />

through mailout/mailback <strong>and</strong><br />

through enumeration (NRFU)<br />

by the share of minorities in a<br />

tract’s population. Information<br />

about April 1st inhabitants of<br />

a housing unit provided by<br />

people not living there on April<br />

1st—known as proxy response<br />

—is treated as nonresponse<br />

here. Figure 7 shows that mail<br />

response rates strongly negatively<br />

correlate with percent<br />

minority. Tracts with populations<br />

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4<br />

Actual/forecast<br />

that are less than 25 percent<br />

minority had about eleven<br />

percentage points higher average<br />

response rates than tracts<br />

with populations that are more<br />

than 75 percent minority. The<br />

correlation is much weaker in<br />

nonresponse follow-up, where<br />

75 percent minority tracts had<br />

approximately three percentage<br />

points lower interview rates.<br />

Nonresponse follow-up thus<br />

reduced the differential undercount<br />

of minorities relative to<br />

the count at the end of the mailback<br />

period.<br />

Figure 8 shows the odds ratios<br />

of selected variables in tractlevel<br />

grouped logistic regressions<br />

of response rates separately<br />

for mailout/mailback<br />

(in blue) <strong>and</strong> nonresponse<br />

follow-up (in red). The results<br />

provide further support for the<br />

story suggested by Figure 7.<br />

Even after controlling for other<br />

factors, minority race/ethnicity<br />

groups have well-below-average<br />

mailout/mailback response<br />

rates, but their nonresponse<br />

follow-up response rates are not<br />

nearly so low. Unemployment<br />

has a positive association with<br />

response rates, but the magnitude<br />

of the effect is very<br />

small. Richer neighborhoods<br />

have slightly higher mailout/<br />

mailback response rates <strong>and</strong><br />

slightly lower nonresponse<br />

follow-up response rates. Areas<br />

with a high concentration of<br />

retirement-aged persons have<br />

very high mailout/mailback<br />

U.S. <strong>Census</strong> <strong>Bureau</strong> Research at the Center for Economic Studies <strong>and</strong> the Research Data Centers: <strong>2010</strong>–<strong>2011</strong> 19