THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

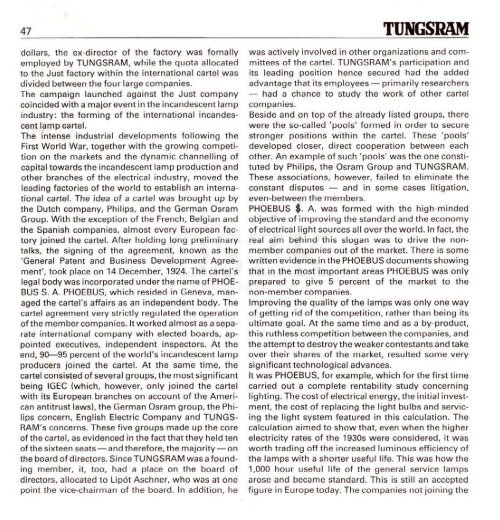

47 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>dollars, the ex-director of the factory was fomallyemployed by <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>, while the quota allocatedto the Just factory within the international cartel wasdivided between the four large connpanies.The campaign launched against the Just companycoincided with a major event in the incandescent lampindustry, the forming of the international incandescentlamp cartel.The intense industrial developments following theFirst World War, together with the growing competitionon the markets and the dynamic channelling ofcapital towards the incandescent lamp production andother branches of the electrical industry, moved theleading factories of the world to establish an internationalcartel. The idea of a cartel was brought up bythe Dutch company. Philips, and the German OsramGroup. With the exception of the French, Belgian andthe Spanish companies, almost every European factoryjoined the cartel. After holding long preliminarytalks, the signing of the agreement, known as the'General Patent and Business Development Agreement',took place on 14 December, 1924. The cartel'slegal body was incorporated underthe name of PHOEBUS S. A. PHOEBUS, which resided in Geneva, managedthe cartel's affairs as an independent body. Thecartel agreement very strictly regulated the operationof the member companies. It worked almost as a separateinternational company with elected boards, appointedexecutives, independent inspectors. At theend, 90—95 percent of the world's incandescent lampproducers joined the cartel. At the same time, thecartel consisted of several groups, the most significantbeing IGEC (which, however, only joined the cartelwith its European branches on account of the Americanantitrust laws), the German Osram group, the Philipsconcern, English Electric Company and TUNGSRAM'S concerns. These five groups made up the coreof the cartel, as evidenced in the fact that they held tenof the sixteen seats — and therefore, the majority — onthe board of directors. Since <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> was a foundingmember, it, too, had a place on the board ofdirectors, allocated to Lipot Aschner, who was at onepoint the vice-chairman of the board. In addition, hewas actively involved in other organizations and committeesof the cartel. <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>'S participation andits leading position hence secured had the addedadvantage that its employees — primarily researchers— had a chance to study the work of other cartelcompanies.Beside and on top of the already listed groups, therewere the so-called 'pools' formed in order to securestronger positions within the cartel. These 'pools'developed closer, direct cooperation between eachother. An example of such 'pools' was the one constitutedby Philips, the Osram Group and <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.These associations, however, failed to eliminate theconstant disputes — and in some cases litigation,even-between the members.PHOEBUS $. A. was formed with the high-mindedobjective of improving the standard and the economyof electrical light sources all over the world. In fact, thereal aim behind this slogan was to drive the nonmembercompanies out of the market. There is somewritten evidence in the PHOEBUS documents showingthat in the most important areas PHOEBUS was onlyprepared to give 5 percent of the market to thenon-member companies.Improving the quality of the lamps was only one wayof getting rid of the competition, rather than being itsultimate goal. At the same time and as a by-product,this ruthless competition between the companies, andthe attempt to destroy the weaker contestants and takeover their shares of the market, resulted some verysignificant technological advances.It was PHOEBUS, for example, which for the first timecarried out a complete rentability study concerninglighting. The cost of electrical energy, the initial investment,the cost of replacing the light bulbs and servicingthe light system featured in this calculation. Thecalculation aimed to show that, even when the higherelectricity rates of the 1930s were considered, it wasworth trading off the increased luminous efficiency ofthe lamps with a shorter useful life. This was how the1,000 hour useful life of the general service lampsarose and became standard. This is still an acceptedfigure in Europe today. The companies not joining the

![Letöltés egy fájlban [4.3 MB - PDF]](https://img.yumpu.com/50159926/1/180x260/letaltacs-egy-fajlban-43-mb-pdf.jpg?quality=85)