Fall 2011 - the Department of Biology - Syracuse University

Fall 2011 - the Department of Biology - Syracuse University

Fall 2011 - the Department of Biology - Syracuse University

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

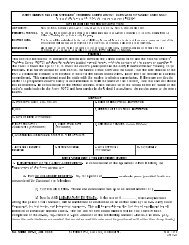

are beautiful and are <strong>of</strong>ten cultivatedin gardens. Some yuccas are relativelyfamous; Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia), forexample, is both <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> a nationalpark in California and a popular U2album.Yuccas are only pollinated by yuccamoths, and <strong>the</strong> relationships between<strong>the</strong> moth and <strong>the</strong> plant has becomeextremely specialized during <strong>the</strong>irevolutionary history. During <strong>the</strong> day<strong>the</strong> small white yucca moths benignlyrest inside yucca flowers, but at night<strong>the</strong>y become bandits, stealthily flittingfrom yucca flower to yucca flower to layeggs and pollinate. The female yuccamoths deposit eggs inside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flowers,hypodermically injecting <strong>the</strong>m into <strong>the</strong>floral tissue using a modified structurethat resembles a needle (similar to <strong>the</strong>stinger <strong>of</strong> a wasp). Just after laying anegg, a female will climb to <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>flower and purposefully pollinate usinga bit <strong>of</strong> pollen that she carries in a ballunder her head. Females have specializedmouthparts used for collecting anddepositing pollen, and <strong>the</strong>se mouthpartsare not found in any o<strong>the</strong>r insect. Suchactive pollination behavior is incrediblyrare, as nearly all pollinators accomplish<strong>the</strong> task by accidentally brushing pollenonto <strong>the</strong> receptive surfaces <strong>of</strong> flowers. Bypurposefully pollinating <strong>the</strong> flower, <strong>the</strong>female yucca moth is ensuring a foodsource for her <strong>of</strong>fspring, since <strong>the</strong> eggswill eventually hatch into small larvae thatfeed exclusively on yucca seeds. In <strong>the</strong>end, <strong>the</strong> plant generally comes out aheadbecause <strong>the</strong> moths pollinate more seedsthan <strong>the</strong> larvae destroy; thus, <strong>the</strong> plantgains an extremely effective pollinator bygiving up a few seeds.My Ph.D. project focused onhow cheaters evolve in mutualisticinteractions, and I took advantage <strong>of</strong>a new discovery that Olle had madewhile conducting field research in <strong>the</strong>southwestern United States. When hebegan working on yucca moths, <strong>the</strong>rewere only a few named species, andhis observations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moth Tegeticulayuccasella led him to believe this entitywas actually a composite <strong>of</strong> severalunrecognized species. A combination<strong>of</strong> DNA sequence analysis andmeasurements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shape and size <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> moths showed that Olle was right,Figure 1: Tegeticula yuccasella in a yucca flower. The female in <strong>the</strong> lower right is laying an egg,and <strong>the</strong> female on <strong>the</strong> left is actively pollinating.and revealed that T. yuccasella consisted<strong>of</strong> at least 14 distinct species. The trulyexciting finding was that two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>senew species were “cheaters,” or mothsthat avoided pollination and laid eggsdirectly into developing fruit. Cheaterscapitalize on <strong>the</strong> efforts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pollinatormoths, and <strong>the</strong>ir larvae feed on yuccaseeds in competition with pollinatormoth larvae. In <strong>the</strong>ory, cheaters shouldoverexploit <strong>the</strong> mutualistic partners byeating all <strong>the</strong> seeds, and <strong>the</strong> final resultwould be extinction <strong>of</strong> all three species.Yet, a quick look at <strong>the</strong> evolutionaryhistory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cheaters shows that<strong>the</strong>y have happily coexisted with <strong>the</strong>mutualistic moths for upwards <strong>of</strong> twomillion years; clearly, cheaters are notdestabilizing <strong>the</strong> mutualism. During<strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> my Ph.D. work, I usedbehavioral studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moths, fieldobservations, and molecular analyses <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> evolutionary histories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pollinatorand cheater moths to examine howcheaters might have evolved. Although<strong>the</strong> evidence remains thin, our bestguess is that cheaters may come intoexistence when a mutualistic interactionis more complex than <strong>the</strong> simple scenario<strong>of</strong> two interacting partners. That is, incircumstances when multiple pollinatormoth species coexist on a singleyucca species, <strong>the</strong>re is an evolutionaryopportunity for one pollinator speciesto cheat because <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r pollinator isstill providing a benefit to <strong>the</strong> plant. Weare still exploring this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis andare learning more about how mutualistscan turn to <strong>the</strong> dark side and becomecheaters.This idea about how communitycomplexity might lead to cheating drewme to think more deeply about how <strong>the</strong>multitude <strong>of</strong> interactions present in acommunity could influence <strong>the</strong> pair-wiseinteraction between mutualist partners.We <strong>of</strong>ten think <strong>of</strong> mutualisms as existingin isolation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir surroundings andignore <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r species. Part<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reason for doing so is one <strong>of</strong>simplification; species <strong>of</strong>ten interact withhundreds <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r species, and tryingto study even just <strong>the</strong> direct effects <strong>of</strong> afew interactions can be challenging. Forinstance, a typical pollination mutualismwill involve a focal plant species that hasOlle PellmyrS12 THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY AT SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY