GRADUATE STUDENT PROFILE:Dawn HigginsonI’ve learned to be vague when strangers ask me what I do. A bluntreply <strong>of</strong> “I study sperm” typically results in a stunned or mildlybemused expression and a quietly uttered response <strong>of</strong> “Oh!” Thatends most conversations with non-biologists.Sperm were discovered in 1677 byAntonie van Leeuwenhoek, a draper bypr<strong>of</strong>ession and an amateur microscopist.In his spare time, he built simple, singlelens microscopes that could magnifyobjects up to 270x, sufficient to seeeven some bacteria. In his letter to <strong>the</strong>Royal Society <strong>of</strong> London describing hisremarkable discovery, he communicated<strong>the</strong> sensitivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> topic:“And if your Lordship should considerthat <strong>the</strong>se observations may disgust orscandalize <strong>the</strong> learned, I earnestly begyour Lordship to regard <strong>the</strong>m as privateand to publish or destroy <strong>the</strong>m as yourLordship see fit.”Fortunately, Leeuwenhoek’s workwas published and attracted considerableattention from scientists at <strong>the</strong> time.However, <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> sperm and eggs in<strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> new individuals was notunderstood or widely accepted until <strong>the</strong>1880s. Today, it is common knowledge thattransfer <strong>of</strong> paternal DNA through spermto an unfertilized egg occurs in all sexuallyreproducing animals.I first became interested in spermwhile working on <strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong>insecticide resistance in <strong>the</strong> pinkbollworm, a pest in cotton fieldsworldwide. The pink bollworm is a smallmoth whose caterpillars eat <strong>the</strong> developingseed heads from which cotton fiber isharvested. In <strong>the</strong> United States, pinkbollworm damage is limited by plantingtransgenic cotton plants, geneticallymodified to produce Bt-toxin protein,<strong>the</strong> gene for which was isolated from<strong>the</strong> bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis. Bttoxinbinds to <strong>the</strong> gut <strong>of</strong> caterpillars; <strong>the</strong>caterpillars stop feeding and eventuallydie. Outside <strong>of</strong> legally required “refuges”in which unmodified cotton is planted,virtually all cotton grown currently istransgenic, potentially resulting in intenseselection for bollworms resistant to Bttoxin.After <strong>the</strong> widespread introduction<strong>of</strong> Bt cotton to <strong>the</strong> US agricultural system,<strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> pink bollworms inArizona fields resistant to Bt-toxin actuallydropped from a surprisingly high level at<strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> introduction to undetectablelevels. As part <strong>of</strong> a master’s <strong>the</strong>sis, Iwas tasked with understanding whyresistance to Bt-cotton was not found in<strong>the</strong> field despite <strong>the</strong> ease <strong>of</strong> generatingresistant pink bollworm strains in <strong>the</strong> lab.Experiments conducted by members <strong>of</strong>my research group at <strong>the</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Arizona revealed that resistant moths wereless likely to survive <strong>the</strong> winter than mothssusceptible to Bt. Additionally, I foundthat resistant males sired fewer <strong>of</strong>fspringthan susceptible males when competingto fertilize a female’s eggs, despite havingsimilar mating frequencies and fertility.While trying to understand this result, Ilearned that moths and butterflies producetwo types <strong>of</strong> sperm: one type participatesin fertilization while <strong>the</strong> second typecontains no DNA. Sperm lacking DNA<strong>of</strong>ten makeup more than 90 percent <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> total sperm transferred to females. Iwas completely stunned by this fact. Whyspend so much energy making spermthat couldn’t fulfill <strong>the</strong> primary function <strong>of</strong>fertilization? Follow-up research by my labgroup found that resistant males transferfewer sperm, <strong>of</strong> both types, to femalesthan do males susceptible to Bt-cotton.After finishing my M.S. degree at <strong>the</strong><strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Arizona and a brief hiatusworking in a <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Montana labstudying bark beetles (<strong>the</strong> scourge <strong>of</strong>western forests, killing whole stands <strong>of</strong>trees and increasing <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong>large-scale wildfires), I still couldn’t stopthinking about <strong>the</strong> bizarre infertile sperm<strong>of</strong> moths. I found myself borrowing all<strong>the</strong> sperm-related books from <strong>the</strong> libraryand decided that I wanted to investigate<strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> unusual sperm traits in adepth that only a Ph.D. dissertation wouldallow. I started looking at grad schools andfound <strong>the</strong> best place in North America,and arguably <strong>the</strong> world, to pursue mystudies was in <strong>the</strong> lab <strong>of</strong> Scott Pitnickin <strong>the</strong> <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Biology</strong> at SU. Iapplied, was accepted, and spent <strong>the</strong> nextseveral years happily submerged in <strong>the</strong>study <strong>of</strong> how reproductive traits are shapedby selection resulting from male-malecompetition for mates and female choice<strong>of</strong> sires.My doctoral research focused onunderstanding why sperm that share acommon function, fertilization, have suchdiverse morphology. For example, withininsects alone, any one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four mainconstituents <strong>of</strong> sperm—<strong>the</strong> acrosome,nucleus, mitochondria or flagellum—maybe absent or form <strong>the</strong> most prominentfeature <strong>of</strong> sperm morphology. The answeris, in part, that sperm do much more thanjust fertilize an egg. In <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> specieswith internal fertilization (most terrestrialand some aquatic animals), sperm mustnavigate <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten complex chemicaland physical environment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> femalereproductive tract to locate and fuse withan egg. Sperm also <strong>of</strong>ten undergo <strong>the</strong>final stages <strong>of</strong> maturation outside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> male that produced <strong>the</strong>m. Inaddition,Hisperm typically have to competewith <strong>the</strong> sperm <strong>of</strong> rival males within <strong>the</strong>female while avoiding competition withsibling sperm. The diverse morphology <strong>of</strong>sperm is believed to reflect adaptations toovercome e <strong>the</strong>se many challenges facingsperm.To test ideas about how spermmorphology ogy evolves, I have focused ondiving beetles es (Dytiscidae). The grouphas been around since <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>dinosaurs, and today <strong>the</strong>re are nearly4,000 living species. Diving beetlescan be found in almost any lake, pond,stream, or puddle worldwide. Prior to mywork, <strong>the</strong> sperm <strong>of</strong> a handful <strong>of</strong> closelyrelated species had been examined.From this limited sample, it was evidentthat <strong>the</strong> sperm <strong>of</strong> diving beetles <strong>of</strong>tenjoin toge<strong>the</strong>r at <strong>the</strong> head to form amulti-sperm conjugate that swims in a14THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY AT SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

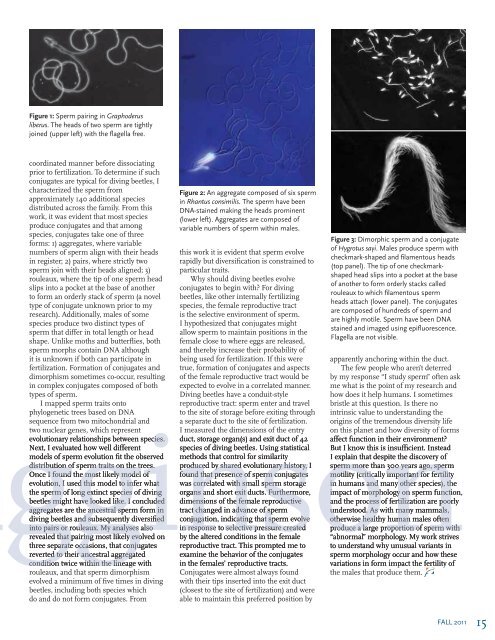

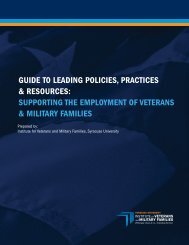

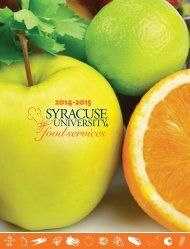

Figure 1: Sperm pairing in Graphoderusliberus. The heads <strong>of</strong> two sperm are tightlyjoined (upper left) with <strong>the</strong> flagella free.coordinated manner before dissociatingprior to fertilization. To determine if suchconjugates are typical for diving beetles, Icharacterized <strong>the</strong> sperm fromFigure 2: An aggregate composed <strong>of</strong> six spermapproximately 140 additional species in Rhantus consimilis. The sperm have beendistributed across <strong>the</strong> family. From this DNA-stained making <strong>the</strong> heads prominentwork, it was evident that most species (lower left). Aggregates are composed <strong>of</strong>produce conjugates and that amongvariable numbers <strong>of</strong> sperm within males.species, conjugates take one <strong>of</strong> threeFigure 3: Dimorphic sperm and a conjugateforms: 1) aggregates, where variable<strong>of</strong> Hygrotus sayi. Males produce sperm withnumbers <strong>of</strong> sperm align with <strong>the</strong>ir heads this work it is evident that sperm evolvecheckmark-shaped and filamentous headsin register; 2) pairs, where strictly two rapidly but diversification is constrained to(top panel). The tip <strong>of</strong> one checkmarkshapedhead slips into a pocket at <strong>the</strong> basesperm join with <strong>the</strong>ir heads aligned; 3) particular traits.rouleaux, where <strong>the</strong> tip <strong>of</strong> one sperm head Why should diving beetles evolve<strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r to form orderly stacks calledslips into a pocket at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r conjugates to begin with? For divingrouleaux to which filamentous spermto form an orderly stack <strong>of</strong> sperm (a novel beetles, like o<strong>the</strong>r internally fertilizingheads attach (lower panel). The conjugatestype <strong>of</strong> conjugate unknown prior to my species, <strong>the</strong> female reproductive tractare composed <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> sperm andresearch). Additionally, males <strong>of</strong> some is <strong>the</strong> selective environment <strong>of</strong> sperm.are highly motile. Sperm have been DNAspecies produce two distinct types <strong>of</strong> I hypo<strong>the</strong>sized that conjugates mightstained and imaged using epifluorescence.sperm that differ in total length or head allow sperm to maintain positions in <strong>the</strong>Flagella are not visible.shape. Unlike moths and butterflies, both female close to where eggs are released,sperm morphs contain DNA althoughit is unknown if both can participate infertilization. Formation <strong>of</strong> conjugates anddimorphism sometimes co-occur, resultingin complex conjugates composed <strong>of</strong> bothtypes <strong>of</strong> sperm.I mapped sperm traits ontophylogenetic trees based on DNAand <strong>the</strong>reby increase <strong>the</strong>ir probability <strong>of</strong>being used for fertilization. If this weretrue, formation <strong>of</strong> conjugates and aspects<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> female reproductive tract would beexpected to evolve in a correlated manner.Diving beetles have a conduit-stylereproductive tract: sperm enter and travelto <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> storage before exiting throughapparently anchoring within <strong>the</strong> duct.The few people who aren’t deterredby my response “I study sperm” <strong>of</strong>ten askme what is <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> my research andhow does it help humans. I sometimesbristle at this question. Is <strong>the</strong>re nointrinsic value to understanding <strong>the</strong>gginsonsequence from two mitochondrial and a separate duct to <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> fertilization. origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tremendous diversity lifetwo nuclear genes, which representI measured <strong>the</strong> dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entrythis planet and how diversity <strong>of</strong> formsevolutionary relationships between species.duct, storage organ(s) and exit duct <strong>of</strong> 42affect function <strong>the</strong>ir environment?Next, I evaluated how well differentspecies <strong>of</strong> diving beetles. Using statisticalBut I know this is insufficient. Insteadmodels <strong>of</strong> sperm evolution fit <strong>the</strong> observedmethods that control for similarityI explain that despite <strong>the</strong> discovery <strong>of</strong>distribution <strong>of</strong> sperm traits <strong>the</strong> trees.produced by shared evolutionary history, Isperm more than 300 years ago, spermOnce I found <strong>the</strong> most likely model <strong>of</strong>found that presence <strong>of</strong> sperm conjugatesmotility (critically important for fertilityevolution, on, I used this model to infer whatwas correlated with small sperm storagehumans and many o<strong>the</strong>r species), <strong>the</strong><strong>the</strong> sperm <strong>of</strong> long extinct species <strong>of</strong> divingorgans and short exit ducts. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,impact <strong>of</strong> morphology sperm function,beetles might have looked like. I concludeddimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> female reproductiveand <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> fertilization are poorlyaggregates are <strong>the</strong> ancestral sperm form tract t changed advance <strong>of</strong> spermunderstood. As with many mammals,diving beetles and subsequently diversifiedconjugation, indicating that sperm evolveo<strong>the</strong>rwise healthy human males <strong>of</strong>teninto pairs or rouleaux. My analyses alson response to selective pressure createdproduce a large proportion <strong>of</strong> sperm withrevealed that pairing most likely evolved onthree separate occasions, that conjugatesreverted ed to <strong>the</strong>ir ancestral aggregatedby <strong>the</strong> altered conditions in <strong>the</strong> femalereproductive tract. This prompted me toexamine <strong>the</strong> behavior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conjugates“abnormal” morphology. My work strivesto understand why unusual variants insperm morphology occur and how <strong>the</strong>secondition twice within <strong>the</strong> lineage withrouleaux, and that sperm dimorphismevolved a minimum <strong>of</strong> five times in divingbeetles, including both species whichdo and do not form conjugates. Fromin <strong>the</strong> females’ reproductive tracts.Conjugates were almost always foundwith <strong>the</strong>ir tips inserted into <strong>the</strong> exit duct(closest to <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> fertilization) and wereable to maintain this preferred position byvariations in form impact <strong>the</strong> fertility <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> males that produce <strong>the</strong>m.FALL <strong>2011</strong>15