You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

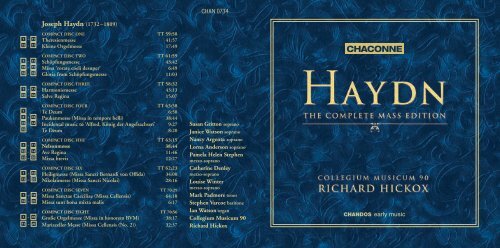

<strong>CHAN</strong> <strong>0734</strong>Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)COMPACT DISC ONE TT 59:581 - 11 Theresienmesse 41:5712 - 17 Kleine Orgelmesse 17:49COMPACT DISC TWO TT 61:591 - 11 Schöpfungsmesse 43:4212 - 17 Missa ‘rorate coeli desuper’ 6:4918 - 19 Gloria from Schöpfungsmesse 11:03COMPACT DISC THREE TT 58:321 - 11 Harmoniemesse 43:1312 - 16 Salve Regina 15:07COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 63:381Te Deum 6:502 - 12 Paukenmesse (Missa in tempore belli) 38:4413 - 14 Incidental music to ‘Alfred, König der Angelsachsen’ 9:2715Te Deum 8:20COMPACT DISC FIVE TT 63:151 - 11 Nelsonmesse 38:4412 - 14 Ave Regina 11:4615 - 20 Missa brevis 12:27COMPACT DISC SIX TT 62:231 - 12 Heiligmesse (Missa Sancti Bernardi von Offida) 34:0013 - 23 Nikolaimesse (Missa Sancti Nicolai) 28:16COMPACT DISC SEVEN TT 70:291 - 18 Missa Sanctae Caeciliae (Missa Cellensis) 64:1019 - 20 Missa sunt bona mixta malis 6:17COMPACT DISC EIGHT TT 70:561 - 10 Große Orgelmesse (Missa in honorem BVM) 38:1711 - 20 Mariazeller Messe (Missa Cellensis (No. 2)) 32:37Susan Gritton sopranoJanice Watson sopranoNancy Argenta sopranoLorna Anderson sopranoPamela Helen Stephenmezzo-sopranoCatherine Denleymezzo-sopranoLouise Wintermezzo-sopranoMark Padmore tenorStephen Varcoe baritoneIan Watson organCollegium Musicum 90Richard Hickox<strong>CHAN</strong>DOS early music

COMPACT DISC TWOMissa solemnis (Hob. XXII:13) 43:42in B fl at major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeurSchöpfungsmesse (Creation Mass)1I Kyrie 6:202II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 7:123‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 3:474III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 2:065‘Et incarnatus est’ – 2:586‘Et resurrexit’ – 2:487‘Et vitam venturi saeculi’ 1:358IV Sanctus 3:059V Benedictus 6:3610VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 3:2111‘Dona nobis pacem’ 3:41Susan Gritton • Pamela Helen StephenMark Padmore • Stephen Varcoe soloistsMissa ‘rorate coeli desuper’ (Hob. XXII:3) 6:49in G major • in G-Dur • en sol majeur12I Kyrie – 0:4913II Gloria – 0:4114III Credo – 2:0015IV Sanctus – 0:4216V Benedictus – 0:4917VI Agnus Dei 1:48Gloria from ‘Schöpfungsmesse’ 11:03Haydn’s alternative Gloria for Empress Marie Therese18II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 7:1219‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 3:51TT 61:59COMPACT DISC THREEMass (Hob. XXII:14) 43:13in B fl at major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeurHarmoniemesse1I Kyrie 8:072II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 2:053‘Gratias agimus’ – 5:184‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 3:105III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 2:466‘Et incarnatus est’ – 3:497‘Et resurrexit’ 4:258IV Sanctus 2:599V Benedictus 4:0710VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 3:1311‘Dona nobis pacem’ 2:574 5

Salve Regina (Hob. XXIIIb:1) 15:07in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur12I ‘Salve Regina’ – 5:2013II ‘Ad te clamamus’ – 3:0614III ‘Eia ergo, advocata nostra’ 2:1815IV ‘Et Jesum’ – 0:5216V ‘O clemens, o pia’ 3:30Nancy Argenta soloistTT 58:32COMPACT DISC FOUR1Te Deum (Hob. XXIIIc:1) 6:50in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeurNancy Argenta • Catherine DenleyMark Padmore • Stephen Varcoe soloistsMissa in tempore belli (Hob. XXII:9) 38:44in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeurPaukenmesse2I Kyrie 4:453II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 2:414‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ – 5:295‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 2:196III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 1:117‘Et incarnatus est’ – 4:108‘Et resurrexit’ 4:259IV Sanctus 2:1010V Benedictus 5:4511VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 2:4512‘Dona nobis pacem’ 2:38Nancy Argenta • Catherine DenleyMark Padmore • Stephen Varcoe soloistsIncidental music to‘Alfred, König der Angelsachsen’ 9:2713Aria des Schutzgeistes (Hob. XXX:5a) 6:09(The Guardian Spirit’s Aria)Jacqueline Fox speakerNancy Argenta soloist14Chor der Dänen (Hob. XXX:5b) 3:12(Chorus of the Danes)15Te Deum (Hob. XXIIIc:2) 8:20in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeurTT 63:38COMPACT DISC FIVEMass (Hob. XXII:11) 38:44in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineurNelsonmesse (Nelson Mass)1I Kyrie 4:262II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 3:243‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ – 4:294‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 2:445III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 1:366‘Et incarnatus est’ – 4:126 7

7‘Et resurrexit’ 3:348IV Sanctus 2:309V Benedictus 5:5910VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 3:0011‘Dona nobis pacem’ 2:33Susan Gritton • Pamela Helen StephenMark Padmore • Stephen Varcoe soloistsAve Regina (Hob. XXIIIb:3) 11:46in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur12‘Ave Regina coelorum’ – 5:4113‘Gaude Virgo gloriosa’ – 1:1514‘Valde, o valde’ 4:50Susan Gritton soloistMissa brevis (Hob. XXII:1) 12:27in F major • in F-Dur • en fa majeur15I Kyrie 1:1516II Gloria 1:3717III Credo 2:4218IV Sanctus 1:0319V Benedictus 3:1120VI Agnus Dei 2:40Susan Gritton • Pamela Helen Stephen soloistsTT 63:15COMPACT DISC SIXMissa Sancti Bernardi von Offida (Hob. XXII:10) 34:00in B fl at major • in B-Dur • en bémol majeurHeiligmesse1I Kyrie 4:142II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 2:083‘Gratias agimus tibi’ – 3:304‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 2:415III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 1:246‘Et incarnatus est’ – 3:407‘Et resurrexit’ – 1:598‘Et vitam venturi saeculi’ 1:569IV Sanctus 1:2210V Benedictus 5:0911VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 3:0712‘Dona nobis pacem’ 2:33Missa Sancti Nicolai (Hob. XXII:6) 28:16in G major • in G-Dur • en sol majeurNikolaimesse13I Kyrie 3:1714II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 3:3015‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 1:0316III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 0:3917‘Et incarnatus est’ – 3:238 9

18‘Et resurrexit’ – 1:1919IV Sanctus: ‘Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus’ – 1:3620‘Pleni sunt coeli’ 0:4821V Benedictus 5:3922VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 3:1323‘Dona nobis pacem’ 3:29TT 62:23COMPACT DISC SEVENMissa Cellensis (Hob. XXII:5) 64:10in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeurMissa Sanctae Caeciliae1I Kyrie: ‘Kyrie eleison’ – 2:522‘Christe eleison’ – 3:213‘Kyrie eleison’ 3:024II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 2:555‘Laudamus te’ – 4:266‘Gratias agimus tibi’ – 2:327‘Domine Deus, Rex coelestis’ – 6:048‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ – 5:029‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ – 3:2310‘Cum Sancto Spiritu’ – 0:2711‘In gloria Dei Patris’ 2:5012III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 3:4113‘Et incarnatus est’ – 7:2714‘Et resurrexit’ 5:0215IV Sanctus 1:3016V Benedictus 5:1317VI Agnus Dei: ‘Agnus Dei’ – 1:5918‘Dona nobis pacem’ 2:16Missa sunt bona mixta malis (Hob. XXII:2) 6:17in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur19I Kyrie 2:3920II Gloria 3:37TT 70:29COMPACT DISC EIGHTMissa in honorem BVM (Hob. XXII:4) 38:17in E fl at major • in Es-Dur • en mi bémol majeurGroße Orgelmesse1I Kyrie 5:412II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 1:063‘Gratias agimus tibi’ – 6:044‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 1:495III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 2:046‘Et incarnatus est’ – 4:067‘Et resurrexit’ 3:398IV Sanctus 1:569V Benedictus 6:0310VI Agnus Dei 5:4510 11

Missa Cellensis (No. 2) (Hob. XXII:8) 32:37in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeurMariazeller Messe11I Kyrie 4:2012II Gloria: ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ – 1:3513‘Gratias agimus tibi’ – 5:0914‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’ 1:5115III Credo: ‘Credo in unum Deum’ – 1:3516‘Et incarnatus est’ – 4:1317‘Et resurrexit’ 2:1318IV Sanctus 2:0619V Benedictus 5:0720VI Agnus Dei 4:22TT 70:56Susan Gritton soprano (CD 2, 5, 7 & 8)Janice Watson soprano (CD 1)Nancy Argenta soprano (CD 3 & 4)Lorna Anderson soprano (CD 6)Pamela Helen Stephen mezzo-soprano (CDs 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 & 7)Catherine Denley mezzo-soprano (CD 4)Louise Winter mezzo-soprano (CD 8)Mark Padmore tenorStephen Varcoe baritoneIan Watson organ (CD 8)Collegium Musicum 90Richard HickoxIn comparison with his contribution to thequartet, the symphony, opera and manyother genres, Haydn’s tally of fourteen massesis a small one. His musical upbringing inRohrau, Hainburg and, especially, Viennawas almost entirely within the confines of theCatholic Church with its rich tradition ofperformance and composition. A career as achurch musician would have been a perfectlynatural development for the young Haydn.In the 1750s, however, he became esteemedas an innovative composer of instrumentalmusic, and at the Esterházy court from 1761onwards circumstances ensured that he neverdeveloped a continuing career as a composerof church music. Although from 1766 Haydnwas nominally in charge of church musicat the court, Prince Nicolaus Esterházy wasnot particularly interested in promoting it,preferring instrumental music and opera(unlike his grandson, also Nicolaus, who wasto be associated with the six late masses).Nevertheless, between 1766 and 1772 Haydndid manage to compose four masses, largely,it seems, because he wanted to rather thanbecause he was required to do so: the firstHaydn: The Complete Mass EditionMissa Cellensis, the Missa sunt bona mixtamalis, the Große Orgelmesse and the MissaSancti Nicolai.When Haydn returned to Vienna in 1795from the second of his two visits to London,he resumed his duties as Kapellmeister to theEsterházy family. By 1802 he had servedthe Esterházy court for forty-one years, andthe reigning prince, Nicolaus II, was hisfourth master. Musical life of the court hadbeen at a low ebb since 1790, and becauseof the diminished interest of his employers,the court had lost its position as a leadingcultural centre in the Austrian Monarchy. Theresident opera company had been disbanded,the summer palace at Eszterháza was nolonger in use, and there was no permanentlyconstituted orchestra. Haydn was retainedas Kapellmeister, mainly out of loyalty, butalso because the Esterházy family couldrightly claim some of the glory that this nowworld-famous figure had earned. The Prince’smain cultural interest lay in amassing a largecollection of paintings (later displayed to thepublic), but he was also interested in churchmusic and re-activated the musical life of the12 13

court, encouraged in this by his wife, PrincessMarie Hermenegild (1768–1845). Insteadof the symphonies and operas of formeryears, Haydn was now required to compose anew mass every year for the nameday of thePrincess; each mass was performed on thenearest convenient Sunday to 8 September,the Feast of Our Lady. These celebrationsbecame a central feature in the socialcalendar of the Esterházy court, celebratedwith fireworks, visits by acting troupes whopresented a season of plays and operas, anda special mass service at the local Bergkirche.Between 1796 and 1802 Haydn composedsix masses for these occasions: the Heiligmesse,Paukenmesse, Nelsonmesse, Theresienmesse,Schöpfungsmesse and Harmoniemesse.COMPACT DISC ONEThe Theresienmesse is the fourth of theseries of six late masses, and like all Haydn’schurch music it circulated quickly throughthe Austrian territories. The Empress MarieTherese was an avid collector of Haydn’smusic and soon added it to her library; fromthis association grew the view that the workhad been composed for the Empress, hencethe misleading nickname Theresienmesse.The vocal forces of the mass are thecustomary soprano, alto, tenor and basssoloists plus chorus, written in such a way thatthere is a continual interweaving of single andmassed voices. Unique to this mass, however,is the orchestral sonority. The absence of aregularly constituted court orchestra encouragedHaydn to score each of the six masses in adifferent manner. To the basic sonority ofstrings and organ continuo, the Theresienmesseadds the warm sounds of clarinets and bassoons,and the brilliance of trumpets and timpani.These varied orchestral hues are immediatelyapparent in the slow introduction, encouraginga mood that is variously lyrical and dramatic.The introduction unostentatiously hints at theshape of the themes that are to be used in thesubsequent Allegro: the fugue subject associatedwith the text ‘Kyrie eleison’ and the secondary,more lightly-scored idea associated with thetext ‘Christe eleison’. While the emotionalresponse of the Kyrie (and the mass as a whole)is typical of Austrian church music of thetime – an appropriate aural equivalent to thestunningly decorated Baroque and Rococochurches of the area – what is distinctive isthe desire to reinforce this tradition with apowerful sense of musical argument that ismodern rather than backward-looking. Twofurther instances will have to suffice.At the end of the Credo Haydn has afugue, as was the norm, to draw the lengthymovement to a climactic conclusion. ButHaydn’s fugue is not a dry-as-dust, dutifulconclusion; it is founded on an infectiouslyjaunty subject that proclaims the joy aswell as the certainty of eternal life. TheBenedictus always constituted a musical andspiritual highlight in settings of the massin the Classical period. The Benedictus inthe Theresienmesse is one of Haydn’s mostcaptivating. After four movements inB flat major – some twenty-five minutes ofmusic – the Benedictus switches magicallyto a luminous G major; the delightfullytuneful orchestral introduction leads to anextended setting of the text, culminating in acentral climax when the music swings roundto B flat major, the home key, so that thecomposer can feature trumpets and timpanito punctuate a martial declamation of thetext.The traditional three statements of ‘AgnusDei, qui tollis peccata mundi’ are set in anAdagio tempo and in G minor. This mood ofseverity is swept aside by the return to B flatmajor and a fast tempo for the final section,‘Dona nobis pacem’. As always, Haydn is notmerely asking for peace and deliverance, butalso rejoicing in the fact that they are to begranted. There is no anguish or doubt, just awonderful certainty.The Missa brevis Sancti Joannis deDeo (Kleine Orgelmesse) is a much earlierwork, dating from the 1770s; althoughthe autograph is extant, rather unusuallyfor Haydn he did not date it. The ‘Johnof God’ of the title is a reference to thepatron saint of the Barmherzigen Brüder(the Hospitallers of St John of God), aholy order represented in many towns andcities in the Austrian Monarchy. Theywere esteemed for their medical servicesto the community, and were noted fortheir learned understanding of botany andmedicine (the hospice next to their churchin Vienna prepares and dispenses potions tothis day). The order also believed stronglyin the palliative powers of music which,consequently, played a more than usuallyprominent part in their worship. TheEszterházy family were regular benefactorsof the order and Haydn himself had playedthe violin in services in the church inVienna in the 1750s; many smaller piecesof church music (especially advent music)from the composer’s youth can be associatedwith the order. This mass was probablywritten for the church in Eisenstadt. It is amuch smaller church than the Bergkirche,where most of the six late masses were fi rstperformed. As a result the instrumental14 15

forces could well have consisted of theminimum of two violins, one cello, onedouble bass and organ; the vocal forcesare unlikely to have numbered more thantwo or three per part. It is a Missa brevis,a work designed not for an important holyday or to celebrate a nameday of a secularpatron, but for routine services. Thelengthier portions of the text, the Gloriaand Credo, are set polytextually, that is,several clauses are sung simultaneously so asto proceed through the text in approximatelya quarter of the time. This was a commoncharacteristic of such masses, but Haydnbalances such apparent perfunctoriness withmore expansive treatment of other parts ofthe text. The opening and closing movementsof the mass are in a slow tempo throughout,providing a contemplative frame for thework. But it is the Benedictus that offersthe spiritual and musical highlight of thesetting. It is a luxurious aria for solo soprano,accompanied by solo organ and strings. Thecomposer may well have played the organhimself in early performances in Eisenstadtand almost certainly he would have broughta singer from the Eszterházy court for thisaria, simultaneously a celebration of a life inChrist and Haydn’s tribute to the work of theHospitallers of St John of God.COMPACT DISC TWOThe Schöpfungsmesse (‘Creation’ Mass)is the fi fth of the six late masses. By thetime of its composition Haydn was aninternational fi gure whose symphonies,quartets and, most sensationally, theoratorio The Creation dominated musicaltaste, but he was still also the dutifulKapellmeister at the Esterházy court. Hebegan work on the latest nameday mass on28 July 1801, completing it in just underseven weeks in readiness for performanceon 13 September at the Bergkirche inEisenstadt.As there was no longer a steady and fullyconstituted orchestra available at the court,many players had to be engaged on an ad hocbasis. From 1800 onwards a reasonably fullcomplement of wind players was availableand so the Schöpfungsmesse was scored foroboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets,timpani, strings and organ. In the section ofthe Credo dealing with the mystery of theVirgin Birth, the ‘Et incarnatus est’, Haydnhad it in mind to depict the Holy Spiritin the centuries-old manner, as a dove. Inmusic such an image is often represented bya flute. Since Haydn did not have a playerat his disposal he gave the line to the organ,indicating that it should be played on a flutestop, the only time in his career that thecomposer indicated an organ registration.According to one anecdote Haydn ‘dartedlike a weasel’ to the organ to play the parthimself, much to the amusement of theperformers.The vocal forces are the customary SATBchoir and four soloists (the latter sometimesbriefly expanded to six). Instruments andvoices are integrated into one seamlesstexture: the instruments are as much vocalistsdeclaiming the text as the singers areinstrumentalists projecting a complementarymusical argument. As well as unconsciousmanipulation of forces, Haydn shows, too,how easily his mature language can movebetween melody with accompaniment andthe most intricate contrapuntal writing.The latter never sounds stolid or spuriouslyauthoritative, the fugue at the end of theGloria, for instance, featuring a delightfullyunorthodox chromatic theme.Haydn had always enjoyed a reputationas a humorist in music, providing anythingfrom witty manipulation of language toopen guffaws. The nickname of this mass,‘Creation’ Mass, draws attention to one ofHaydn’s most incautious musical pranks.In the Gloria, listeners and performerssteeped in Austrian church music wouldhave expected a change of tempo from fast toslow at either the clause ‘Gratias agimus tibi’or ‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’. Instead Haydn’sorchestra carries blithely on in a fast tempo,quoting Adam and Eve’s music from theoratorio The Creation, music associated withthe text ‘The dew dropping morn, Oh how shequickens all!’; the instrumentation, includingthe very secular-sounding horns, is the same.In the mass the bass soloist then enters andrepeats the tune with the very different words‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ before the choir inan abrupt change of tempo asks for mercy,‘Miserere nobis’. The joke is a multi-layeredone: the salacious innuendo of the quotation,the sudden realization that the composer has‘forgotten’ to change the tempo and the mockcontrition of the choir. At least one personwas offended: the Empress Marie Therese;Haydn had to recompose this passage in hercopy of the mass. This alternative version toois recorded here. Listeners might feel that theoffence is mitigated rather than removed, sincethe wrong tempo and the abrupt change at‘Miserere nobis’ remain; only the quotation ofthe theme from The Creation is removed.To any charges of mischievous improprietyHaydn would no doubt have replied that itwas the impropriety of a believer, projectedin order to assert the essential security of his16 17

vision. This is the overwhelming impressionthat the mass leaves.For nearly forty years Haydn had kepta draft catalogue of his compositions, theso-called Entwurf-Katalog. Sometimes in hisold age Haydn rediscovered a work from hisyouth and added it to the catalogue. Oneof the most problematical of these very lateentries is the one described as Missa roratecoeli desuper in G; Haydn noted too a veryshort musical incipit. The work remainedlost until the twentieth century when itwas discovered as work ascribed to Haydn’steacher, Georg Reutter, a respected composerof church music. Later, a source attributed toHaydn was discovered, several further sourcesnaming it as a work of Reutter, and twoclaiming it as the work of a certain FerdinandArbesser. To aggravate an already complicatedsituation, the musical beginning recorded byHaydn in his catalogue is not quite the sameas that in these rediscovered sources. In hisold age Haydn had an imperfect memoryof what he had composed, most infamouslysanctioning the publication of the so-calledOp. 3 quartets under his name, works thatare undoubtedly spurious. One plausibleexplanation is that the mass represents thejoint work of master and pupil, Reutter andHaydn, dating from the late 1740s whenHaydn was still a choirboy at the Hofkapellein Vienna.The unambitious nature of the workitself is not necessarily a reflection ofHaydn’s inexperience. Short settings of themass in which the Gloria and Credo areset polytextually (here four different linesof the text are sung simultaneously) andwith the minimum of accompaniment (twoviolin lines plus continuo) are frequentlyencountered in the period. ‘Rorate coelidesuper’ refers to the Introitus in the LiberUsualis used for the fourth Sunday in Advent,indicating that at least one performancetook place on that date. Advent and Lentwere two seasons in the church calendarwhen the musical ambition of masses wasseverely curtailed. This mass may well be anintriguing piece of juvenilia by Haydn, but itis also a useful reminder of how perfunctorychurch music in eighteenth-century Austriacould be.COMPACT DISC THREEHaydn’s Harmoniemesse was the composer’slast major work, written at the age of seventyin 1802. Although he was to live for a furtherseven years and was able to invent manypromising musical ideas, the increasinglyfrail old man lacked the physical and mentalstamina to attend to their potential. TheHarmoniemesse, however, is certainly not thework of a weary composer; neither is it anintroverted, spiritually reclusive work. Thereis no such thing as ‘third period’ Haydn:the enquiring and confident optimism thathad sustained him in over half a century ofcomposition is as keenly felt here as in any ofhis output.The mass is scored for one flute, two oboes,two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, twotrumpets, timpani, strings and organ. It wasstill comparatively unusual for a mass tobe accompanied by an orchestra with a fullwind section – a ‘Harmonie’; the nickname(‘mass with the wind band’) reflects this factrather than implying consistent solo use ofwind instruments. The vocal forces were thecustomary SATB choir and soloists, the latteraugmented by an extra soprano and tenor fora few bars near the end of the Credo.In the opening Kyrie, the typical franknessof the main melodic statement is underminedby the chromatic note that begins the secondphrase, and throughout this commandingmovement soloists and choir enhance thisfeeling of a supplication made in the hopefulknowledge of a response; the literal meaningof Haydn’s tempo marking, Poco adagio,seems very appropriate here – ‘a little at ease’.Carefully wrought musical argument is alsotypical of the mass as a whole, allowingthose passages of simple melody andaccompaniment, such as the ‘Gratias agimustibi’ (in the Gloria) and the ‘Et incarnatus est’(in the Credo), to yield a touching simplicity,and the fugues at the end of the Gloria andCredo to impart tremendous energy.It is perhaps the tone of the Benedictusthat is the least expected. Rather than beingan expansive, lyrical movement for soloists,it is a brisk Molto allegro featuring thechorus, and a melody that is sung played inpianissimo octaves over a restless accompaniment,evoking the quiet excitement,rather than the comfort, of a life in Christ.Most of the mass is set in the home keyof B flat. For the beginning of the AgnusDei, Haydn turns magically to G major,emphasized by extended writing for thesoloists and members of the ‘Harmonie’,creating an optimistic mood that is cruciallytempered by chromatic harmony and, later,by a single ominous timpani roll. A briskfanfare heralds the ‘Dona nobis pacem’, asection of increasing assurance but with someexcitable mirth from the ‘Harmonie’ alongthe way.The Salve Regina in E Major belongs tothe opposite end of Haydn’s career, and can18 19

justly be regarded as his first major work. Inhis twenties the composer had led a freelanceexistence in Vienna, playing the violin andthe organ, directing some church services,accompanying singing lessons, giving hisown keyboard lessons, providing music fora German opera company, and acceptingmore and more commissions for instrumentalworks. His formal education in music hadbeen patchy and he was still learning his craft:I wrote diligently, but not correctly, untilat last I had the good fortune to learn thetrue fundamentals of composition fromthe celebrated Herr Porpora.Nicola Porpora (1686 –1768) had beenone of Europe’s leading opera composerswith a career that had taken him from hisnative Italy to Germany, England (where hewas a rival of Handel) and, finally, Austria.For several years in the 1750s Haydn actedas an accompanist in singing lessons givenby Porpora. The first work by the youngcomposer to reveal Porpora’s professionalism isthis Salve Regina, probably dating from 1756.The work is scored for soprano soloist,SATB choir, strings (but without violas, as wastypical of much Austrian church music) andorgan. The alternation throughout of elaboratewriting for the soloist and more chordalwriting for the choir is highly effective. Theformer, in particular, shows several Italianatetricks of the trade picked up from Porpora: thelong note (messa di voce) opening, the gentlyaffecting rests in the middle of phrases andthe agile decoration. It is the chorus, however,who end the work, with a quiet, contemplativecadence on the word ‘Maria’.COMPACT DISC FOURThe Missa in tempore belli (Mass in time ofwar) was Haydn’s own title for the Mass inC major, appearing on the autograph scoreand in the composer’s own catalogue of hismusic. During the summer and autumn of1796, four years into the European war thatfollowed the French Revolution, Austrianforces were under attack on two fronts: theItalian territories were being conquered byFrench troops under the inspired leadershipof the young Napoleon, while on the westernfront French and Austrian troops werefighting for control of southern Germany.For the first time since the Turkish threat in1683, Austria sensed an imminent invasion ofits heartland.It was against this background that Haydn,at the age of sixty-four, composed this mass.It was first performed in the Piaristenkirchein Vienna on 26 December 1796 as part ofa service celebrating the admission to thepriesthood of Joseph Franz von Hofmann,whose father, rather appropriately, wasImperial and Royal Paymaster for War. Thefollowing year, rather than composing a newmass for the annual nameday celebrationsof Princess Marie Hermenegild, Haydnintroduced the Esterházy family to his Missain tempore belli.Given Haydn’s advanced age and the factthat the original commission for the masswas for a service in Vienna and the secondperformance was an equally local occasion,in the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt, it wouldhave been understandable had the composerwithdrawn into his background and written agentle, comforting setting of the text. Instead,he made an inspired effort to incorporatethe troubled mood of the times into themusic, so as to project with even greaterforce the conviction of his Christian belief.Incorporating references to battles in a masswas not something new, but the potency ofthe integration found in the Missa in temporebelli was not to be surpassed until Beethoven’sMissa solemnis, composed a quarter of acentury later.‘In tempore belli’ first suggests itself, verysubtly, in the Benedictus. Traditionally, thetext of this movement was set indulgently,with an expansive, lyrical style and anatmosphere that was gently ecstatic. Here,however, the opening orchestral introductionin C minor, with its short phrases leading to apowerful climax, suggests an entirely differentmood; when the four solo voices enter itis not with expansive melodies but with acomparatively short motif, nervously sharedbetween all four voices. Later, the music turnsto C major, yet the memory of the unsettlingC minor remains.In the following Agnus Dei the menace ismore explicit; the three traditional statementsof the prayer are undermined by ominousdrumbeats and insistent fanfares on windinstruments. In an interview with his firstbiographer, Georg August Griesinger, Haydnsaid the drumbeats should sound ‘as if oneheard the enemy approaching in the distance’.The opening movements of the mass –Kyrie, Gloria, Credo and Sanctus – providea more conventional background to the‘tempore belli’, but one that is informed withthe full range of techniques and emotionstypical of Haydn’s six late masses: easyintegration of soloists and chorus, simplemelodies as well as intricate fugues, andgreat vitality alongside sections of exquisitebeauty. When, after the Agnus Dei, windinstruments herald the ‘Dona nobis pacem’with a forceful flourish, it is not merely peace20 21

that is granted but a victory that transcendsthe ‘tempore belli’: a secure vision deliveredwith irresistible joy.While the mass had an appeal that wasvividly contemporary, it also tapped into afirm tradition of Catholic church music inAustria in that its key, C major, was inevitablyassociated with the sound of trumpets andtimpani, projecting the overlapping qualitiesof praise, celebration and triumph. Three ofthe remaining items on this disc explore thesame idiom.The first Te Deum in C was composed inthe early 1760s when Haydn had just enteredthe service of the Esterházy family. The precisecircumstances of its composition are notunknown; most likely it was first performedas part of the wedding celebrations in January1763 that marked the marriage of CountAnton Esterházy and Countess Marie ThereseErdödy. As well as the sound of C majorcoloured by trumpets and timpani, the workhas the typical three-part design common insettings of the Te Deum at the time: briskouter sections framing a contrasting slowsection for the words ‘Te ergo quaesumus’(We therefore pray).A few months before the first performanceof the Missa in tempore belli in 1796, Haydnwas in Eisenstadt taking part in the festivitiesto celebrate the nameday of the Princess. Aswell as a church service with a new mass (theMissa Sancti Bernardi), there was a visit froma travelling theatre company, who performedover two dozen operas and plays during asix-week stay. On 9 September, the actualnameday, the play was Alfred, König derAngelsachsen (Alfred, King of the Anglo-Saxons), a free adaptation of an English playby Alexander Bicknell. Haydn provided threeitems of incidental music: an aria, a chorusand a duet, the last of which is incomplete.The aria is sung by the Guardian Spirit whocomforts the imprisoned Queen Elvida. It isaccompanied by a wind sextet of clarinets,horns and bassoons, and Queen Elvida’sresponses are spoken against this wonderfullyevocative background. The chorus is sung bythe victorious Danes, celebrating a particularlybloodthirsty victory over the Anglo-Saxons. Inmood and technique it foreshadows the Missain tempore belli which was to occupy Haydn’senergies in the next few months; at the words‘Trompeten und Pauken verkünden den Sieg’(Trumpets and drums herald the victory)there is even an anticipation of the beginningof the ‘Dona nobis pacem’ from the Mass.This is the first recording of the chorus.The second Te Deum in C wascommissioned by the Empress Marie Therese,probably in 1799. As an avid admirerof Haydn’s music she organised privateconcerts at the Imperial and Royal Courtto explore his music. While sharing manygeneric features in common with the earlierTe Deum – C major, trumpets and timpani,and a three-part design – its colossal rawenergy seems to sum up not only Haydn’slong experience as a composer but thewhole heritage of such music. Although itwas commissioned by the Empress, its fi rstknown performance took place in Eisenstadtin September 1800 as part of that year’snameday celebrations.COMPACT DISC FIVEThe year 1798 was one of the mostremarkable in Haydn’s long life. He hadrecently completed his oratorio, The Creation,an ambitious work that had consumed hisenergy and imagination for over two years.The first few months of the year were takenup with the less fulfilling, but equally timeconsumingtask of supervising the copyingof the scores and the parts in readiness for aseries of four semi-public performances ofthe work that took place in late April/earlyMay. As someone who was now lauded asAustria’s leading artistic figure, Haydn alsodirected two charity performances in Aprilof the choral version of the Seven Last Wordsof Christ.By the end of May, Haydn was physicallyexhausted and, according to one source,had to be confi ned to his rooms for a fewweeks to rest. He moved with the Esterházyfamily to Eisenstadt for the summermonths, knowing that by September hewas expected to produce a new mass forthe Princess. Normally, Haydn liked tohave up to three months to write such awork, but in 1798, probably because ofhis exhaustion, he did not begin the massuntil 10 July, completing it by 31 August, aremarkably short period of fi fty-three days.As well as composing against the clock,Haydn was faced with another restriction.Prince Esterházy was attempting to reduceexpenditure at court and had dismissed the‘Harmonie’ (windband) that Haydn hadbeen able to call upon for previous namedayperformances. His solution was to make avirtue of this situation and to score the massfor strings (always available in Eisenstadt),organ (played by the composer himself),three trumpet players (specially hired for theoccasion) and timpani (a local player). Theresulting sonority – sparse yet capable alsoof great theatricality – is a highly distinctivefeature of the mass.22 23

The mass was first performed at theMartinkirche in Eisenstadt on 23 September.It must have been about this time thatHaydn entered the work in his catalogue ofcomposition, calling it ‘Missa in angustiis’,that is, ‘Mass in straitened times’. This wasnever the formal title of the work – Haydn’stitle was ‘missa’ – and it may well have beena wry reference to the limited time in whichhe had composed it, and to its restrictedinstrumental forces. Two years later, whenNelson visited Eisenstadt, the mass wasperformed in his presence, giving rise tothe much more familiar nickname, theNelsonmesse. Later commentators lookingfor ‘Nelson’-like qualities in the work seizedon the coincidence that in the summer of1798, while Haydn was working on the mass,the British fleet under Nelson’s leadershipachieved a stunning victory over Napoleon’sMediterranean fleet in the Battle of Aboukir.But the news of this victory did not reachHaydn until after he had finished the mass.It is a mistake, therefore, to make a directlink between the mass and Nelson, and toassociate ‘straitened times’ with specific eventsin contemporary European history.Nobody, however, would wish to deny theextraordinary tension that informs certainmovements of this mass, one that makesthe fi nal resolution into unalloyed joy souplifting. The fi rst movement is in D minor,the only time in an orchestral mass thatHaydn sets the text in a minor key. Theunusual orchestral forces make their impactimmediately, joined later by the chorusand a particularly fl amboyant part for thesolo soprano. D minor is next heard in theBenedictus which, rather than having thecustomary grace and lyricism, is a nervousmovement, simmering with a latent powerthat is fi nally unleashed when the threetrumpets play an insistent fanfare againstthe contradictory text of ‘Blessed is he whocomes in the name of the Lord’. In a waythat Beethoven would have admired, thiselement of fear associated with D minor isjuxtaposed with, and ultimately overcomeby, radiant music in D major.One of the most telling aspects of Haydn’sstatus at the end of the eighteenth centuryis that music originally composed for theCatholic liturgy was performed extensivelyas concert music in Protestant Europe. Thepublishing firm of Breitkopf & Härtel inLeipzig issued five of the six late masses inprint (including the ‘Nelson’ Mass) andcontinually pressed Haydn for further itemsof sacred music. In his old age Haydn had thetouching experience of re-discovering somelong-forgotten works and selling them toBreitkopf & Härtel, sometimes amending theinstrumentation. One of these rediscoverieswas the Missa brevis in F major, probablyHaydn’s first mass and originally composedwhen he was seventeen or eighteen. ‘Whatspecially pleases me in this little work’, hetold one of his biographers, ‘is the melody,and a certain youthful fi re…’. The massis scored for chorus, strings and organ,with two delightfully florid parts for solosopranos. Its neat, unambitious natureshould not be taken as the inexperience of ayouthful composer; rather the reverse, for itwas a very skilful setting of the text designedto further Haydn’s career as a composer ofchurch music in mid-century Vienna. Thisneatness is partly due to the composer’sdecision to follow the frequent practiceof setting the ‘Dona nobis pacem’ to thesame music as the Kyrie. Equally typicalof contemporary practice is the Credo,in which several lines of the text are sungsimultaneously, and the Benedictus, whichadopts the opposite approach: a high ratio ofmusic to words.Also from the early part of Haydn’s careeris the Ave Regina. While nothing is knownabout the circumstances of its composition,it is likely to date from the mid-1750s whenHaydn’s melodic style (especially for solosoprano) shows a deliberate attempt to absorbcontemporary Italian mannerisms. The threemovements are scored for solo soprano,chorus, strings and organ.COMPACT DISC SIXDuring the summer of 1796 Haydn workedon a mass for the forthcoming namedaycelebrations. As was often the custom (thereare three instances in Haydn’s output), thework was given a title that featured a saint’sname: Missa Sancti Bernardi von Offida.Bernard of Offida was a seventeenth centuryCapuchin monk who had been beatified byPope Pius VI in 1795. The saint’s day was11 September which, in 1796, happenedalso to be the nameday of Princess MarieEsterházy. Haydn’s work, therefore, was atribute both to a lowly monk and a graciouspatron and, though direct evidence is notforthcoming, it was almost certainly fi rstperformed on that date.Haydn had not composed a massfor fourteen years and this work has anunmistakable feeling of the composerreconnecting with his roots in Austria afterthe excitement of two visits to London. Asthe opening of the Kyrie suggests, this is themost openly tuneful of Haydn’s late masses;24 25

at the beginning of the Sanctus he wrote inthe margin next to the tenor line ‘Heilig’,drawing gentle attention to a well-knownGerman hymn tune ‘Heilig, Heilig’ (Holy,Holy) which is concealed, like a favouredkeepsake, in the middle of the texture.This musical reference occasioned the laternickname for the mass, Heiligmesse. Morepoignant is the ‘Et incarnatus’ section inthe Credo, where yet another simple melodyis developed as a three-part canon forsolo voices. But, as throughout this mass,simplicity of utterance is only the preludeto something much more probing; in thispassage Haydn uses his unrivalled masteryof orchestral colour as he explores theresonances of the text, high treble sounds,pizzicato strings and the sound of clarinetsfor the mystery of the Virgin Birth (‘Etincarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex MariaVirgine, et homo factus est’), male voicesand low, bowed strings for a minor-keyversion of the same melody when the textturns to the death of Christ (‘Crucifi xusetiam pro nobis, sub Pontio Pilato’).A second distinctive feature of this mass –certainly in comparison with a work like the‘Nelson’ Mass (1798) – is the comparativelysmall role given to the vocal soloists. Most ofthe setting is led by the choir, and it is theywho usually transform the tunefulness into aradiant energy that is equally captivating.A more familiar saint is commemoratedin the Missa Sancti Nicolai (Nikolaimesse),from 1772. St Nicolaus’s day falls on6 December, the beginning of Advent,and the work was probably performedto celebrate the nameday of the thenPrince Esterházy, another Nicolaus, thegrandfather of Nicolaus II. Although he wasby far the most supportive of the Esterházyprinces, that particular year, 1772, was adifficult one for Kapellmeister and patron.Because of fi nancial stringency there weresuggestions that the musical retinue mighthave to be cut back, and the lengthy stayin the summer palace of Eszterháza provedunpopular with the players who had beenforced to leave their families in Eisenstadt.Haydn, who was always a master diplomaton behalf of his musicians, composed the‘Farewell’ Symphony in which the playersleave the stage one by one until only twoviolins are playing; the prince took thehint and immediately allowed the courtto return to Eisenstadt. The Missa SanctiNicolai may well have been the second stageof Haydn’s diplomacy; he was certainly notrequired to compose church music as partof his duties as that traditional side of thecourt’s activities had gone into decline atthe expense of opera and instrumental music.Nicolaus would have been surprised as well asdelighted that his Kapellmeister had composeda mass especially for his nameday.The work belongs to a distinct typeof mass associated with Advent, oftenseparately catalogued in eighteenth-centurysources as missae pastorales (pastoral masses).Traditional musical techniques designedto conjure up the familiar intermingledimages of the loving Shepherd, the birth ofChrist in a stable, and the shepherds in thefield characterise this mass, as they do anynumber of contemporary pastoral masses:gently lilting metres (the opening andclosing movements are in 6/4, an unusualmetre in the Classical period), simplemelodies and a propensity for the top of thetexture to move in parallel thirds, especiallydownwards, as if in obeisance. Even thechoice of key, G major, is characteristic; itwas often favoured for pastoral masses todistinguish them in sonority from the largenumber of masses in C. Since the main aimis to comfort rather than to uplift, Haydnuses the frequently encountered device ofrepeating the music of the Kyrie for the‘Dona nobis pacem’. The fi nal impression,therefore, is the same as the initial one.COMPACT DISC SEVENThe Missa Cellensis is one of two massesby Haydn with this title. ‘Cellensis’ refers toMariazell, a small town nestled high in thehills in the Styrian countryside to the southof the Danube. Generations of AustrianCatholics have travelled on foot to the town,often in gatherings of several thousand,to pay homage to a simple rustic carvingof the Virgin Mary that is placed on anincongruously opulent altar. In his late teensHaydn had made such a pilgrimage. Thefi rst ‘Mariazell mass’, recorded here, datesfrom 1766, five years into the composer’sservice at the Esterházy court. Beyond thefact that the work has something to do withthe famous pilgrimage church nothingis known about the circumstances of itscomposition. Since the church in Mariazellhad very limited musical resources themass is unlikely to have been intended forperformance there; much more likely is aperformance in Vienna, at one of the manyservices that honoured the shrine or wereassociated with pilgrimages from the city toMariazell. Later, the mass acquired anothername, Missa Sanctae Caeciliae, as the resultof a likely (but hitherto undocumented)performance at one of the annual serviceson 22 November promoted in Vienna by the26 27

so-called Musical Congregation to honourthe patron saint of music.That the original occasion for whichthe mass was composed was a particularlysplendid one is suggested by the ambition ofHaydn’s work. It is by far the longest settingof the liturgical text by the composer, onethat was clearly intended to take its placealongside the grandest masses of the Viennesetradition by Fux, Reutter and others. Haydnhad not composed a mass since the end ofthe 1740s and there is a palpable sense ofrevelling in the challenge, in much the sameway as Mozart was to do when writing theMass in C minor (K427). Like that workHaydn’s mass is an example of what is todayusually called a ‘cantata mass’, that is thesingle movements of the Ordinary dividedinto several, musically complete numbers,so that instead of the typical six movementsfound in most Haydn masses, the MissaCellensis has eighteen. The text ‘Laudamuste’, for instance, would normally be presentedas part of the fast opening section of theGloria, accounting typically for about thirtyseconds or so of music; here, it is set apartas a complete aria for solo soprano, with alengthy orchestral introduction and a gooddeal of ostentatious vocal decoration. In mostsettings of the mass in Haydn’s Austria thechorus would expect to have to master twofugues, at the end of the Gloria and theend of the Credo. The Missa Cellensis hasfive fugues in total: a complete movementfor the second ‘Kyrie eleison’, a gravelybeautiful setting of ‘Gratias agimus tibi’,the customary ‘In gloria Dei Patris’ and ‘Etvitam venturi’, and, to end the work, anintricate double fugue setting the text ‘Donanobis pacem’. To bind together the longestsection of the mass, the Credo, Haydn usesa well-established procedure in eighteenthcenturysettings, that of reiterating theinitial affi rmative word ‘Credo’ (I believe)several times, always sung by a sopranosoloist in florid semiquavers in a choralcontext that is predominantly syllabic.Apart from the scope of the work, a fi nallasting memory of the Missa Cellensis is thesplendour of its sonority: C major colouredby energetic fi guration from trumpets andtimpani. Again, this association of keyand sonority for Haydn, his musicians andthe Mariazell pilgrims was a familiar one,celebrated repeatedly in the church musicof the Viennese tradition. Few works,however, reveal the same verve and sense ofcommitment as Haydn’s Missa Cellensis.Two years later, in 1768, Haydn beganwork on a very different kind of mass,described in his thematic catalogue as Missasunt bona mixta malis. For over 200 yearsthe work was lost, until it was discovered ina farmhouse in Northern Ireland in 1983. Itis an incomplete work, consisting of a Kyriemovement and the Gloria as far as the clause‘Gratias agimus tibi’. Scored only for SATBvoices with the support of continuo, it is anexample of the so-called stylus a cappella,liturgical music composed for performanceduring Lent and Advent when orchestralaccompaniment was deemed inappropriate.This is a sizeable, forgotten repertoire ineighteenth-century Austria that includedmusic by Haydn’s contemporaries as well asby composers from the Italian Renaissance,especially Palestrina who was celebrated asthe begetter of the style. But, as Haydn’smass reveals almost immediately, it is notpastiche Palestrina; instead, the vocaltexture is invariably mixed with featuresof eighteenth-century style, includingsequence, chromatic harmony, pedal pointsand a fi rm sense of key rather than mode.The significance of the title must be viewedagainst this hybrid stylistic background.‘Sunt bona mixta malis’ (the good mixedwith the bad) was a saying in commonuse at the time. Late in his life, Haydn,with typical self-deprecation, said that hisoutput in general was ‘mala mixta bonis’,and Beethoven, too, used the remark on atleast one occasion. It is clear from Haydn’sautograph manuscript that the aphorism wasadded to the title page as an ironic commentalongside the more prosaic, but correct, titleof ‘Missa a 4tro voci alla Cappella’.Apprentice composers in Vienna were oftengiven the task of writing such masses to showtheir developing mastery of counterpoint;an intriguing example by Salieri, to nameonly one, survives. Haydn’s schoolmasterishcomment on his own music is typically wry: itis a competent piece of work, but because ofthe stylistic exigencies of the stylus a cappellait is not a convincing one by a composer whohad already demonstrated his mastery of allkinds of music. It was probably for this reasonthat Haydn lost interest in the work andabandoned it.While modern listeners will regard the massas a curiosity, they will be struck too by thesimilarity of some of the thematic ideas in theKyrie to those found in the first movement ofMozart’s Requiem. In truth, both composerswere using ideas that were common musicalproperty. Mozart’s Requiem has accruedenough fanciful baggage without beingburdened by the view that it was indebted toHaydn’s Missa sunt bona mixta malis.28 29

COMPACT DISC EIGHTHaydn composed the Missa in honoremBVM (Mass in honour of the Blessed VirginMary) in 1768 or 1769 (the latter is morelikely), its title indicating that it was initiallyperformed on one of the many Marianfeastdays in the church calendar, thoughprecise details are unknown. When, at a laterstage, the composer entered the mass in a draftcatalogue that he kept of his works, he gave itanother title, Missa Sancti Josephi, suggestingthat another performance had been on StJoseph’s day, 19 March, easily remembered bythe composer since it was his own nameday.It is a very individual work, quite unlikeany other mass by the composer. It is set in thevery unusual key for a mass from this periodof E flat major, and instead of the expectedoboes, has parts for two cors anglais. Thiswas a favourite, if occasional, tone colour ofHaydn’s in the 1760s and 1770s, found infour operas (Acide, La canterina, Le pescatriciand L’incontro improvviso), SymphonyNo. 22 (‘Philosopher’) and the Stabat Mater.The cor anglais parts in the mass are notespecially soloistic but the doleful sound ofthe instrument provides an earnestness thatpervades the whole work. Haydn’s use ofthe organ as an occasional solo instrument,which reflected a distinct tradition in Austrianchurch music, also gave rise to the appropriatenickname Große Orgelmesse (Great OrganMass) – distinguishing it from the KleineOrgelmesse (Small Organ Mass). The organ’sappearance at the beginning of the work istypically decorative, a careful counterpoise tothe simplicity of the Kyrie as a whole. In theBenedictus it dominates the score, with anextended concertante part that accompaniesthe quartet of solo singers and creates theperfect aural complement to the ornaterococo decoration found in many churchesin Haydn’s Austria. After the Benedictus, theorgan reverts to its basic role as a continuoinstrument providing background support.Then, suddenly, at the end of ‘Dona nobispacem’ (a jaunty movement in 6/8 markedPresto) it interjects a couple of passages ofnervous frivolity, a very typical touch bya composer for whom the Catholic faithembraced the full range of human emotions.The Missa Cellensis dates from 1782 and,again, very little of certainty is known aboutthe circumstances of its composition. Haydn’sautograph has the title ‘Missa Cellensis. Fattaper il Signor Liebe de Kreutzner’ which couldbe idiomatically translated as ‘A Cellensismass. Composed for Mr Liebe de Kreutzner’.Kreutzner, who was a retired military officer,had been ennobled in 1781 and, traditionally,it has been assumed that the new masswas associated with a pilgrimage of thanksand celebration undertaken by Kreutzner.An alternative interpretation of Haydn’sannotation has been put forward, however.Kreutzner may have been a member of theViennese brotherhood that honoured andsupported Mariazell pilgrimages, and the masscould have been commissioned by him onbehalf of the brotherhood.Unlike the Große Orgelmesse, this workis firmly in the broad tradition of Austrianmass composition, most obviously reflectedin the choice of C major, with its associatedresplendent use of trumpets and timpani.As a solitary work that stands approximatelymidway between the four masses of 1766–72and the six masses of 1796–1802, the secondMissa Cellensis has features in commonwith both groups of works. As in the GroßeOrgelmesse, the ‘Et incarnatus est’ in the Credois set as a tenor solo in the minor key, but inthe Missa Cellensis it begins in A minor beforemodulating in a very unorthodox manner toC minor, the kind of challenge that Haydnliked to pose in his quartets and symphonies.In both works the chorus re-enters for theensuing ‘Crucifixus’, singing appropriatelytortuous chromatic lines followed bymeasured repeated notes for ‘sepultus est’(was buried). The Kyrie, on the other hand,looks forward to similar movements in the sixlate masses in that the fast section is laid outin full sonata form, with the ‘Christe eleison’constituting the development section.The Benedictus is the oddest movementin the Missa Cellensis, completely unlike thatin the Große Orgelmesse. It begins in a severeG minor with all the stylistic features of abaroque aria: unison strings, dotted rhythms,and sequences. The music was taken, withsome minor adjustments, from Haydn’s operaIl mondo della luna where, sung by Ernesto,it had expressed the sentiment that the courseof true love does not run smooth. Here isseems to be deliberately unsettling, the hopeof a life in Christ being tempered by a senseof mystery and fear. Haydn was to return tothis view of the text in the Harmoniemesse and,most sensationally, the Nelsonmesse. The minorkey, C once more, returns for the Agnus Dei,a clear three-fold statement of the prayer asdemanded by liturgical practice. The Allegrowhich follows, ‘Dona nobis pacem’, is a fugue,but much more intricate in its polyphonythan the one in the Große Orgelmesse; it is, infact, the longest fugue in the mass, a display ofexuberant learning for the Mariazell pilgrims.© David Wyn Jones30 31

Winner of the 1994 Kathleen FerrierMemorial Prize, Susan Gritton appearsregularly in recital throughout Britain andworldwide, at venues such as the AmsterdamConcertgebouw and the Lincoln Center, NewYork. Her concert experience is extensiveand includes performances at the WienerKonzerthaus and the Berlin Philharmonie, aswell as at the BBC Proms, Edinburgh Festivaland Salzburg Mozartwoche. On the operaticstage she has appeared as Mařenka (TheBartered Bride) at The Royal Opera, CoventGarden; in the title role of Theodora at theGlyndebourne Festival; as Cleopatra (GiulioCesare) at Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich;Belinda (Dido and Aeneas) at DeutscheStaatsoper, Berlin; and Marzelline (Fidelio) atRome Opera. Whilst a Company Principalat English National Opera she sang Pamina(Die Zauberfl öte), Nannetta (Falstaff ) and theVixen in The Cunning Little Vixen, amongother roles. Her latest recordings for <strong>Chandos</strong>include The Hummel Mass Edition, the firstvolume of which won a 2003 GramophoneAward.Janice Watson studied at the GuildhallSchool of Music and Drama and first cameto prominence as a winner of the KathleenFerrier Memorial Prize. In addition to being aregular guest with both Welsh National Operaand English National Opera, she has sungin opera houses all round the world in suchroles as Musetta, Pamina, Countess Almaviva;Vitellia, Arabella and Elettra (Idomeneo),Daphne, Arabella and Eva (Die Meistersingervon Nürnberg), Ellen Orford, Micaela andthe Marschallin. In her worldwide concertappearances she has worked with conductorsRoger Norrington, André Previn, MichaelTilson-Thomas, Sir Colin Davis, RiccardoChailly, Frans Brüggen, Sir Neville Marrinerand Bernard Haitink. In her <strong>Chandos</strong>discography are Janáček’s Jenůfa (<strong>CHAN</strong>3106), Vaughan Williams’ The PoisonedKiss (<strong>CHAN</strong> 10120), the award-winningrecording of Britten’s Peter Grimes (<strong>CHAN</strong>9447) and Poulenc’s Gloria (<strong>CHAN</strong> 9341).Nancy Argenta made her professionaldebut in 1983. With a repertoire spanningthree centuries she has been hailed for herperformances of works by Handel andcomposers as diverse as Mahler, Mozart,Schubert and Schoenberg. Her ability toadapt from large-scale orchestral works tochamber music and recitals has earned hergreat recognition and respect. She worksclosely with many distinguished conductorsincluding Trevor Pinnock, ChristopherHogwood, Sir John Eliot Gardiner and SirRoger Norrington, and has sung with thePhilharmonia Orchestra, City of BirminghamSymphony Orchestra, Düsseldorf SymphonicOrchestra, Orchestra of St Luke’s, NewYork, the Toronto and Montreal, Sydneyand Melbourne Symphony Orchestras andthe NACO Orchestra. In opera, concertand recital she has appeared at many leadingfestivals including Aix-en-Provence, MostlyMozart, Schleswig-Holstein and the BBCProms. Born and raised in Canada, NancyArgenta now lives in England.Lorna Anderson studied at the Royal ScottishAcademy of Music and Drama duringwhich time she was awarded several prizesincluding one for the most distinguishedstudent of the year. She won first prize in the1984 Peter Pears and Royal Overseas LeagueCompetitions and in 1986 in Aldeburgh shewon the Purcell-Britten Prize for ConcertSingers. Lorna Anderson has appeared in opera,concert and recital with major orchestras and infestivals throughout Europe including the BBCOrchestras, the London Mozart Players and theRoyal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, andabroad with Ensemble InterContemporain,Residentie Orchestra The Hague and theStuttgarter Kammerchor. She has also appearedat the City of London, Brighton, Edinburghand Aldeburgh festivals. Recent appearancesinclude the Alte Oper, Frankfurt, the NewWorld Symphony in Miami and many recitalsat the Wigmore Hall.Mezzo-soprano Pamela Helen Stephen studiedat the Royal Scottish Academy of Music andDrama, at the Opera Theater Center at Aspen,Colorado, with Herta Glaz, and in Torontowith Patricia Kern, before embarking on aninternational career. Her operatic repertoireincludes Cherubino (Le nozze di Figaro),Donna Clara (The Duenna), Cynthia (Playing),Phoebe (The Yeomen of the Guard ), Moppet/Goose (Paul Bunyan), the Countess of Essex(Gloriana), the title role in Ruth, Nancy(Albert Herring), Hansel (Hansel and Gretel )and Madame Popova (The Bear). In concertshe has performed such works as The Dreamof Gerontius, Les Chants d’Auvergne, Britten’sSpring Symphony and Phaedra, Berlioz’sL’Enfance du Christ and Les Nuits d’été,Rossini’s Stabat Mater and Mozart’s Requiem.Among many <strong>Chandos</strong> recordings are PeterGrimes, The Saint of Bleeker Street, AlbertHerring and The Poisoned Kiss.Catherine Denley has devoted most of hercareer to the oratorio repertoire, with numerous32 33

successful broadcasts and recordings to hername. She grew up in Northamptonshire,graduated from Trinity College of Music, andafter a brief time in the BBC Singers, embarkedon a solo career which has taken her all overthe world. She has recorded a wide repertoireof music including many works by Handel,most recently the title role in Alexander Balus;also Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, Copland’s In TheBeginning, Bruckner’s Requiem, Schubert songswith the Songmakers’ Almanac, Monteverdi’sL’incoronazione di Poppea and Bach’s B minorMass with Richard Hickox, and three highlyacclaimed volumes of Sacred Music by Vivaldi,with the King’s Consort.Mezzo-soprano Louise Winter was born inPreston, Lancashire, and trained at Chetham’sSchool of Music and the Royal NorthernCollege of Music. She has performed withopera companies such as GlyndebourneTouring Opera, The Royal Opera, CoventGarden and English National Opera, as wellas in venues in Toronto, Berlin and Barcelona.Among the roles she has sung are those ofRosina (Il barbiere di Siviglia), Marguerite (LaDamnation de Faust), Sextus (La clemenza diTito), Béatrice (Béatrice et Bénédict), Octavian(Der Rosenkavalier) and the title roles in Serseand Carmen. Louise Winter also performsin recital and concert with orchestras suchas the BBC Symphony Orchestra, City ofBirmingham Symphony Orchestra, BBCNational Orchestra of Wales, Royal ScottishNational Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestraand Montreal Symphony Orchestra.London-born Mark Padmore has won acclaimthroughout the world for the musicality andintelligence of his singing. He is particularlyknown for his committed performances of theEvangelist in Bach’s Passions. His many operaticperformances include Orfeo in Haydn’s Orfeoed Euridice for the Opéra de Lausanne, DonOttavio in Don Giovanni at Aix-en-Provence,and for The Royal Opera, Covent Garden hehas performed the roles of Thespis and Mercurein Rameau’s Platée, Interpreter in VaughanWilliams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and Hot BiscuitSlim in Britten’s Paul Bunyan. He has appearedat many of the world’s most prestigious festivals,including Edinburgh, Salzburg, Spoleto andthe BBC Proms, and recently made his BBCVoices debut with Roger Vignoles in aprogramme of lieder by Beethoven andSchubert.Stephen Varcoe has established a reputationas one of Britain’s most versatile baritones. Hehas made over 125 recordings including worksby Hahn, Chabrier, Finzi, Gurney, Stanford,Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Schubert, NigelOsborne and Thea Musgrave and John Tavener,and has joined Richard Hickox for numerousreleases of Haydn, Beethoven, Vaughan-Williams, Grainger and Britten on <strong>Chandos</strong>.On the concert platform, Stephen has appearedwith orchestras in the UK, Scandinavia,Europe, Japan and North America, workingwith conductors including Brüggen, Christie,Herreweghe, Knussen, Leonhardt, Norrington,Rifkin, Kuijken, Marriner and Malgoire. Hehas regularly taken part in the BBC Proms andfestivals throughout the world and appears inrecital with Roger Vignoles, Graham Johnson,Julius Drake and Ian Burnside. StephenVarcoe’s opera engagements have taken him toAntwerp, Lisbon, Drottningholm (Stockholm)and Tokyo where he has appeared in works byMonteverdi, Haydn, Debussy, Holst, Brittenand Taverner.Ian Watson has made prestigious appearancesand recordings not only as an organist andpianist, but also harpsichordist and conductor.He has been a Principal with the City ofLondon Sinfonia, English Chamber Orchestraand Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, aswell as working with many period instrumentensembles such as The Academy of AncientMusic and English Baroque Soloists. Inaddition he has featured on many film soundtracks,such as Amadeus, Mr Holland’s Opus,Death and the Maiden as well as playing cameoroles in The Madness of King George and JohnOsborne’s England My England.Collegium Musicum 90, jointly founded bySimon Standage and Richard Hickox, is a wellestablishedname for the historical performanceof baroque and classical repertoire which rangesfrom music for chamber ensemble to large-scaleworks for choir and orchestra. It has recordedmore than fifty CDs under its exclusive contractwith <strong>Chandos</strong> Records, has broadcast on BBCRadio 3 and appeared at European and UKfestivals. Highlights of recent seasons haveincluded appearances at the CheltenhamInternational Festival and the BBC Proms aswell as performances in Poland, at the LucerneEaster Festival and at the International HaydnFestival in Eisenstadt, Austria.One of Britain’s most gifted and versatileconductors, Richard Hickox CBE is MusicDirector of Opera Australia, and wasPrincipal Conductor of the BBC NationalOrchestra of Wales from 2000 until 2006when he became Conductor Emeritus. Hefounded the City of London Sinfonia, of34 35

which he is Music Director, in 1971. Heis also Associate Guest Conductor of theLondon Symphony Orchestra, ConductorEmeritus of the Northern Sinfonia, and cofounderof Collegium Musicum 90.He regularly conducts the major orchestrasin the UK and has appeared many times at theBBC Proms and at the Aldeburgh, Bath andCheltenham festivals among others. With theLondon Symphony Orchestra at the BarbicanCentre he has conducted a number of semistagedoperas, including Billy Budd, Hänsel undGretel and Salome. With the BournemouthSymphony Orchestra he gave the firstever complete cycle of Vaughan Williams’ssymphonies in London. In the course of anongoing relationship with the PhilharmoniaOrchestra he has conducted Elgar, Waltonand Britten festivals at the South Bank and asemi-staged performance of Gloriana at theAldeburgh Festival.Apart from his activities at the SydneyOpera House, he has enjoyed recentengagements with The Royal Opera, CoventGarden, English National Opera, ViennaState Opera and Washington Opera amongothers. He has guest conducted such worldrenownedorchestras as the PittsburghSymphony Orchestra, Orchestre de Parisand Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestraand is soon to appear with the New YorkPhilharmonic.His phenomenal success in the recordingstudio has resulted in more than 280recordings, including most recently cycles oforchestral works by Sir Lennox and MichaelBerkeley and Frank Bridge with the BBCNational Orchestra of Wales, the symphoniesby Vaughan Williams with the LondonSymphony Orchestra, and a series of operasby Britten with the City of London Sinfonia.He has received a Grammy (for Peter Grimes)and five Gramophone Awards. RichardHickox was awarded a CBE in the Queen’sJubilee Honours List in 2002, and hasreceived many other awards, including twoRoyal Philharmonic Society Music Awards,the first ever Sir Charles Groves Award, theEvening Standard Opera Award, and theAssociation of British Orchestras Award.I. KyrieKyrie eleison.Christe eleison.Kyrie eleison.II. GloriaGloria in excelsis DeoEt in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te,glorificamus te.Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.Domine Deus, Rex coelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe,Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris,Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationemnostram.Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.Quoniam tu solus sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tusolus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.Cum Sancto Spiritu, in gloria Dei Patris,Amen.III. CredoCredo in unum Deum.Patrem omnipotentem, factorem coeli et terrae,visibilium omnium et invisibilium.Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, FiliumDei unigenitum.Et ex patre natum ante omnia saecula.Deum de Deo, lumen et lumine, Deum verum deDeo vero.I. KyrieLord have mercy.Christ have mercy.Lord have mercy.II. GloriaGlory to God in the highestAnd on earth peace to men of good will.We praise you, we bless you, we adore you, weglorify you.We give you thanks for your great glory,Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father almighty.Lord, only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ,Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father,You take away the sins of the world, have mercyon us.You take away the sins of the world, receive ourprayer.You sit at the right hand of the Father, have mercyon us.For you alone are holy, you alone are the Lord, youalone are the Most High, Jesus Christ,With the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father.Amen.III. CredoI believe in one God.The Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, ofall things visible and invisible.And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begottenSon of God,Born of the Father before all worlds.God from God, light from light, true God fromtrue God.36 37

Genitum, non factum, consubstantialem Patri: perquem omnia facta sunt.Qui propter nos homines, et propter nostramsalutem descendit de coelis.Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto ex Maria Virgineet homo factus est.Crucifixus etiam pro nobis, sub Pontio Pilato,passus et sepultus est.Et resurrexit tertia die, secundum scripturas.Et ascendit in coelum: sedet ad dexteram Patris,Et iterum venturus est cum gloria, judicare vivos etmortuos, cujus regni non erit finis.Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum, et vivificantemqui ex Patre Filioque procedit.Qui cum Patre et Filio simul adoratur etconglorificatur qui locutus est per Prophetas.Et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicamEcclesiam.Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionempeccatorum.Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum,Et vitam venturi saeculi,Amen.IV. SanctusSanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth.Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua.Osanna in excelsis.V. BenedictusBenedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.Osanna in excelsis.Begotten, not made, of one being with the Fatherthrough whom all things were made.For us men and for our salvation he came downfrom heaven.And took flesh by the Holy Spirit from the VirginMary, and became man.He was crucified also for us; under Pontius Pilate hesuffered and was buried.And he rose again on the third day, according tothe scriptures.And ascended into heaven; and sits at the right handof the Father.He will come again in glory to judge the living andthe dead, and his kingdom will have no end.And I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and giverof life, who proceeds from the Father and theSon; who with the Father and the Son is adoredand glorified, who has spoken through theprophets.And in one holy, catholic and apostolic Church.I confess one baptism for the remission of sins.And I look forward to the resurrection of the dead,and the life of the world to come,Amen.IV. SanctusHoly, holy, holy Lord God of power.Heaven and earth are full of your glory.Osanna in the highest.V. BenedictusBlessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.Osanna in the highest.VI. Agnus DeiAgnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.Dona nobis pacem.Salve Regina (CD 3, tracks 12–16)I. Salve Regina, Mater misericordiae: vita, dulcedo,et spes nostra, salve!II. Ad te clamamus, exules filii Evae. Ad te suspiramus,gementes et flentes in hac lacrimarum valle.III. Eia ergo, advocata nostra, illos tuos misericordesoculos ad nos converte.IV. Et Jesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui, nobispost hoc exilium ostende.V. O clemens, o pia, o dulcis Virgo Maria!Te Deum (CD 4, tracks 1 & 15)Te Deum laudamus: te Dominum confitemur.Te aeternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur.Tibi omnes Angeli, tibi caeli et universae potestates:Tibi Cherubim et Seraphim incessabili voceproclamant:Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth.Pleni sunt caeli et terra majestatis gloriae tuae.Te gloriosus Apostolorum chorus: te Prophetarumlaudabilis numerus:VI. Agnus DeiLamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world,have mercy upon us.Grant us peace.Salve Regina (CD 3, tracks 12–16)I. Hail Queen, Mother of mercy: our life, joy andhope, hail!II. We, the banished sons of Eve, cry to thee. We,groaning and weeping in this vale of tears, longfor thee.III. So, as our intercessor, turn those merciful eyesof thine to us.IV. And after this exile show to us Jesus, the blessedfruit of thy womb.V. O gentle one, O holy one, O sweet Virgin Mary!Te Deum (CD 4, tracks 1 & 15)We praise you, O God, we acknowledge you to bethe Lord.All the earth doth worship you, the Father everlasting.To you all Angels cry aloud, the Heav’ns and all thePow’rs therein.To you Cherubim and Seraphim continually do cry,Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth!Heav’n and earth are full of the Majesty of your Glory.The glorious company of the Apostles praises you:the goodly fellowship of the Prophets praises you.38 39

Te Martyrum candidatus laudat exercitus.Te per orbem terrarum sancta confitetur Ecclesia,Patrem immensae majestatis;Venerandum tuum verum, et unicum Filium:Sanctum quoque Paraclitum Spiritum.Tu Rex Gloriae, Christe: tu Patris sempiternus es Filius.Tu ad liberandum suscepturus hominem, nonhorruisti Virginis uterum.Tu devicto mortis aculeo, aperuisti credentibusregna caelorum.Tu ad dexteram Dei sedes, in gloria Patris.Judex crederis esse venturus.Te ergo quaesumus, tuis famulis subveni, quospretioso sanguine redemisti.Aeterna fac cum Sanctis tuis in Gloria numerari.Salvum fac populum tuum Domine, et benedichereditati tuae, et rege eos, et extolle illos usquein aeternum.Per singulos dies, benedicimus te et laudamusnomen tuum in saeculum, et in saeculum saeculi.Dignare Domine die isto sine peccato nos custodire.Miserere nostri Domine.Fiat misericordia tua, Domine super nos,quemadmodum speravimus in te.In te Domine speravi: non confundar in aeternum.The noble army of Martyrs praises you.The Holy Church thro’out all the world doesacknowledge you, the Father of an infinite Majesty.Your honourable, true, and only Son; also the HolyGhost, the Comforter.You are the King of Glory, O Christ: you are theeverlasting Son of the Father.When you tookest upon yourself to deliver man,you did not abhor the Virgin’s womb.When you had overcome the sharpness of death,you did open the Kingdom of Heav’n to allbelievers.You sit at the right hand of God in the Glory ofthe Father.We believe that you shall come to be our judge.We therefore pray you help your servants who youhave redeemed with your precious blood.Make them to be number’d with your Saints inglory everlasting.O Lord save your people and bless your heritage:govern them and lift them up forever.Day by day we magnify your name and we worshipever world without end.Vouchsafe, O Lord, to keep us this day without sin.O Lord have mercy upon us.O Lord let your mercy lighten upon us, as our trustis in you.O Lord in you have I trusted: let me never beconfounded.Ave Regina (CD 5, tracks 12–14)Ave Regina coelorum,Ave Domina Angelorum,Salve radix, salve porta,Ex qua mundo lux est orta.Gaude Virgo gloriosa,Super omnes speciosa.Valde, o valde, o valde decoraEt pro nobis Christum exora.‘Alfred, König der Angelsachsen’(CD 4, tracks 13 & 14)Arie des SchutzgeistesDie SchutzgeisterinAusgesandt vom StrahlenthroneAtm’ ich Tröstung in dein Herz.Trau der Tugend hohem Lohne,Trage standhaft deinen Schmerz.ElvidaBote des Himmels! Lebt mein Alfred? Lebt Edgar?Die SchutzgeisterinHoff’, Elvida! Bange SorgenMachen oft dies Leben schwer;Doch der Zukunft heit’rer MorgenSchwebt aus dunkler Ferne her.Wag’ es nicht, sie zu durchschauenBis der Vorsicht VaterhandDurch den Dornenpfad voll GrauenWege deiner Rettung fand.Hail, Queen of Heaven (CD 5, tracks 12–14)Hail, Queen of Heaven,Hail, Lady of the Angels,Hail, the source, the way,From which light came forth for the world.Rejoice, O glorious Maiden,Splendid above all others.Farewell, O Thou most seemly,And intercede with Christ on our behalf.‘Alfred, King of the Anglo-Saxons’(CD 4, tracks 13 & 14)The Guardian Spirit’s AriaGuardian SpiritDirected by the throne of gloryI breathe comfort into your heart.Trust the lofty reward of virtueBear your grief with courage high.ElvidaMessenger of Heaven! Lives my Alfred? Lives Edgar?Guardian SpiritHope, Elvida! Anxious caresOften make a troubled life;But the future’s joyous morningFloats before us from afar.Do not seek to see beyond itTill the guiding hand of prudenceThrough the thorny path of horrorFinds for you salvation’s way.40 41

ElvidaRettung, Rettung für mich und Alfred!O Dank dir, liebender Geist, ich will ihn fassen,diesen Gedanken, will ihn denken, bis ich nichtmehr zu denken vermag.Die SchutzgeisterinSchützend will ich dich umschweben,Wenn dir Wut und Rache droht;Stärkend deinen Mut beleben;Harr’ auf Gott in deiner Not!Chor der DänenTriumph, Triumph, Triumph dir, Haldane.Die Schlacht ist gekämpft,Der Angel-Sachsen Trotz gedämpft.Wir schreiten auf Leichen ins Lager hinab,Das weite Schlachtfeld ein schauerndes Grab.Wie sind uns’re Schwerter vom Blute so rot.Wir spotteten Gefahr und Tod.Wir lachten des Feindes ohnmächtiger Wut,Sein Todesröcheln befeuert uns’ren Mut.Mit Beute beladen, mit Lorbeern gekröntZieh’n wir daher, die Erde dröhnt,Trompeten und Pauken verkünden den Sieg.Die Götterführten uns selbst in den Krieg.Triumph, Triumph, Triumph dir, Haldane.Die Schlacht ist gekämpft.Der Angel-Sachsen Trotz gedämpft.Wir schreiten auf Leichen ins Lager hinab,Das weite Schlachtfeld ein schauderndes Grab.ElvidaSalvation, Salvation for me and Alfred!Oh thank you, loving spirit, I will fasten upon thisthought, I will think it until I can think no longer.Guardian SpiritI will surround you with protectionWhen beset by rage and vengeance;I will revive your strengthened courage;In your peril wait for God!Chorus of the DanesTriumph, triumph, triumph to you, Haldane.The battle has been fought,Anglo-Saxon defiance is vanquished.We descend to the camp over corpses,The vast battlefield is an awesome grave.How red with blood are our swords.We scorned danger and death.We defied the foe’s impotent rage.His death rattle fired our courage.Laden with booty and crowned with laurelsWe march past and the earth rumbles,Trumpets and drums herald the victory.The gods themselves led us into war.Triumph, triumph to you, Haldane.The battle has been fought,Anglo-Saxon defiance is vanquished.We descend to the camp over corpses,The vast battlefield is an awesome grave.Translation from German: Gery BramallYou can now purchase <strong>Chandos</strong> CDs online at our website: www.chandos.netFor mail order enquiries contact Liz: 0845 370 4994Any requests to license tracks from this CD or any other <strong>Chandos</strong> discs should be made directto the Finance Director, <strong>Chandos</strong> Records Ltd, at the address below.<strong>Chandos</strong> Records Ltd, <strong>Chandos</strong> House, 1 Commerce Park, Commerce Way, Colchester,Essex CO2 8HX, UK. E-mail: enquiries@chandos.netTelephone: + 44 (0)1206 225 200 Fax: + 44 (0)1206 225 201Recording producer Nicholas AndersonSound engineer Ralph CouzensAssistant engineers Richard Smoker, David O’Carroll (CD 7 only), Christopher Brooke (CD 8 only)Editors Jonathan Cooper (CDs 1, 4, 5), Rachel Smith (CDs 6, 7, 8), Peter Newble (CDs 2, 3)Recording venue Blackheath Concert Halls, London; 28-30 June 1995 (CD 1), 22 & 23 December1995 (CD 2), 27–29 November 1996 (CD 3), 20–22 October 1997 (CD 4), 22–24 September 1998(CD 5), 16 –18 April 1998 (CD 6), 18 –20 July 2000 (CD 7), 3 –5 January 2001 (CD 8)Back cover Richard Hickox by Greg BarrettDesign, artwork and typesetting Cassidy Rayne CreativeCopyright Anton Böhm & Sohn, Augsburg (Ave Regina), Carus Verlag, Stuttgart (Missa brevis, Hob.XXII:I), Faber Music Ltd (Nikolaimesse), Editions Mario Bois, Paris (Missa sunt bona mixta malis)Publishers Universal Edition AG (Missa Cellensis, Hob. XXII:5), Alkor Edition Kassel (MissaCellensis (No. 2), Hob. XXII:8)p 1996–2002 <strong>Chandos</strong> Records LtdThis compilation p 2006 <strong>Chandos</strong> Records LtdDigital remastering p 2006 <strong>Chandos</strong> Records Ltd© 2006 <strong>Chandos</strong> Records Ltd<strong>Chandos</strong> Records Ltd, Colchester, Essex CO2 8HX, EnglandPrinted in the EU42 43