For The Defense, July 2010 - DRI Today

For The Defense, July 2010 - DRI Today

For The Defense, July 2010 - DRI Today

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

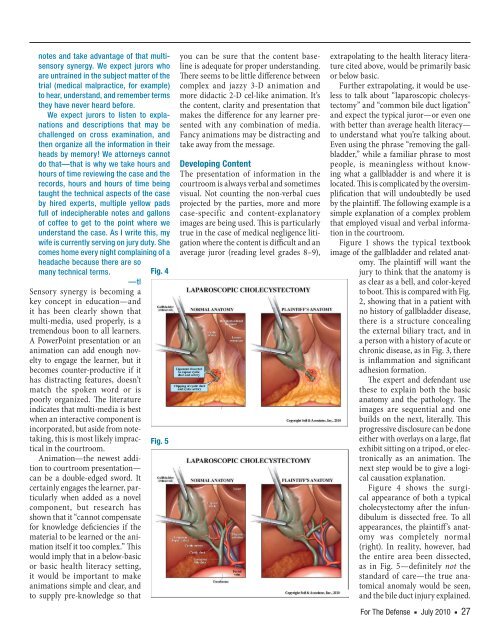

notes and take advantage of that multisensorysynergy. We expect jurors whoare untrained in the subject matter of thetrial (medical malpractice, for example)to hear, understand, and remember termsthey have never heard before.We expect jurors to listen to explanationsand descriptions that may bechallenged on cross examination, andthen organize all the information in theirheads by memory! We attorneys cannotdo that—that is why we take hours andhours of time reviewing the case and therecords, hours and hours of time beingtaught the technical aspects of the caseby hired experts, multiple yellow padsfull of indecipherable notes and gallonsof coffee to get to the point where weunderstand the case. As I write this, mywife is currently serving on jury duty. Shecomes home every night complaining of aheadache because there are somany technical terms.Fig. 4—tlSensory synergy is becoming akey concept in education—andit has been clearly shown thatmulti- media, used properly, is atremendous boon to all learners.A PowerPoint presentation or ananimation can add enough noveltyto engage the learner, but itbecomes counter- productive if ithas distracting features, doesn’tmatch the spoken word or ispoorly organized. <strong>The</strong> literatureindicates that multi- media is bestwhen an interactive component isincorporated, but aside from notetaking,this is most likely impracticalin the courtroom.Fig. 5Animation—the newest additionto courtroom presentation—can be a double- edged sword. Itcertainly engages the learner, particularlywhen added as a novelcomponent, but research hasshown that it “cannot compensatefor knowledge deficiencies if thematerial to be learned or the animationitself it too complex.” Thiswould imply that in a below- basicor basic health literacy setting,it would be important to makeanimations simple and clear, andto supply pre- knowledge so thatyou can be sure that the content baselineis adequate for proper understanding.<strong>The</strong>re seems to be little difference betweencomplex and jazzy 3-D animation andmore didactic 2-D cel-like animation. It’sthe content, clarity and presentation thatmakes the difference for any learner presentedwith any combination of media.Fancy animations may be distracting andtake away from the message.Developing Content<strong>The</strong> presentation of information in thecourtroom is always verbal and sometimesvisual. Not counting the non- verbal cuesprojected by the parties, more and morecase- specific and content- explanatoryimages are being used. This is particularlytrue in the case of medical negligence litigationwhere the content is difficult and anaverage juror (reading level grades 8–9),extrapolating to the health literacy literaturecited above, would be primarily basicor below basic.Further extrapolating, it would be uselessto talk about “laparoscopic cholecystectomy”and “common bile duct ligation”and expect the typical juror—or even onewith better than average health literacy—to understand what you’re talking about.Even using the phrase “removing the gallbladder,”while a familiar phrase to mostpeople, is meaningless without knowingwhat a gallbladder is and where it islocated. This is complicated by the oversimplificationthat will undoubtedly be usedby the plaintiff. <strong>The</strong> following example is asimple explanation of a complex problemthat employed visual and verbal informationin the courtroom.Figure 1 shows the typical textbookimage of the gallbladder and related anatomy.<strong>The</strong> plaintiff will want thejury to think that the anatomy isas clear as a bell, and color- keyedto boot. This is compared with Fig.2, showing that in a patient withno history of gallbladder disease,there is a structure concealingthe external biliary tract, and ina person with a history of acute orchronic disease, as in Fig. 3, thereis inflammation and significantadhesion formation.<strong>The</strong> expert and defendant usethese to explain both the basicanatomy and the pathology. <strong>The</strong>images are sequential and onebuilds on the next, literally. Thisprogressive disclosure can be doneeither with overlays on a large, flatexhibit sitting on a tripod, or electronicallyas an animation. <strong>The</strong>next step would be to give a logicalcausation explanation.Figure 4 shows the surgicalappearance of both a typicalcholecystectomy after the infundibulumis dissected free. To allappearances, the plaintiff’s anatomywas completely normal(right). In reality, however, hadthe entire area been dissected,as in Fig. 5—definitely not thestandard of care—the true anatomicalanomaly would be seen,and the bile duct injury explained.<strong>For</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Defense</strong> n <strong>July</strong> <strong>2010</strong> n 27