Untitled - Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu JagielloÅskiego

Untitled - Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu JagielloÅskiego

Untitled - Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu JagielloÅskiego

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

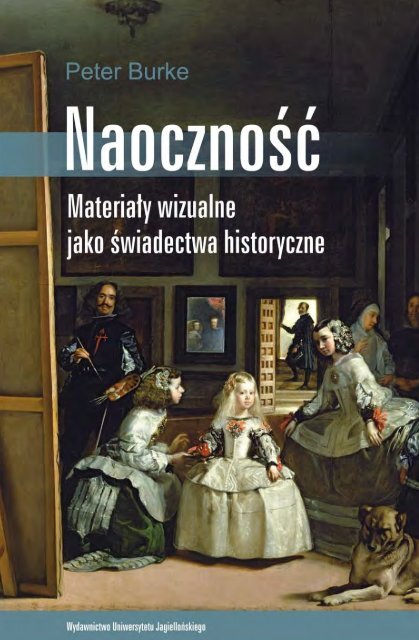

Seria: HistoriaiRecenzenciRedaktor naukowydr hab. Ewa Domańska, prof. UAMprof. dr hab. Krzysztof Zamorskidr Piotr WitekProjekt okładkiJadwiga BurekNa okładce: Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez (1599–1660), Panny dworskie, ok. 1656 (olej napłótnie), Prado, Madrid, Spain/ Giraudon/ The Bridgeman Art LibraryTytuł oryginału: Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical EvidenceEyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence by Peter Burke was firstpublished by Reaktion Books, London, 2001Copyright © Peter Burke 2001Peter Burke, „Interrogating the Eyewitness”, Cultural and Social History,Volume 7, Issue 4, pp. 435–444, © The Social History Society 2010.Published by Berg, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc© Copyright for Polish Translation and Edition by <strong>Wydawnictwo</strong> <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong>JagiellońskiegoWydanie I, Kraków 2012All rights reservedNiniejszy utwór ani żaden jego fragment nie może być reprodukowany, przetwarzany i rozpowszechnianyw jakikolwiek sposób za pomocą urządzeń elektronicznych, mechanicznych,kopiujących, nagrywających i innych oraz nie może być przechowywany w żadnym systemieinformatycznym bez uprzedniej pisemnej zgody Wydawcy.Podręcznik akademicki dotowany przez Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa WyższegoISBN 978-83-233-3382-1www.wuj.pl<strong>Wydawnictwo</strong> <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong> JagiellońskiegoRedakcja: ul. Michałowskiego 9/2, 31-126 Krakówtel. 12-631-18-81, 12-631-18-82, fax 12-631-18-83Dystrybucja: tel. 12-631-01-97, tel./fax 12-631-01-98tel. kom. 506-006-674, e-mail: sprzedaz@wuj.plKonto: PEKAO SA, 80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325

Pamięci Boba Scribnera

Spis treściPrzedmowa i podziękowania .......................................................... 9Spis ilustracji .................................................................................. 11Wprowadzenie do wydania polskiego:„Przesłuchując naocznego świadka” ................................................ 17Wprowadzenie: świadectwo obrazów ............................................. 271 Fotografie i portrety ........................................................................ 392 Ikonografia i ikonologia .................................................................. 533 Święte i nadprzyrodzone ................................................................ 664 Władza i protest ............................................................................. 795 Kultura materialna przez pryzmat obrazów .................................... 1016 Wizerunki społeczeństwa ................................................................ 1257 Stereotypy Innego ........................................................................... 1468 Narracje wizualne ........................................................................... 1649 Od świadka do historyka ................................................................ 18310 Poza ikonografię? ............................................................................ 19511 Historia kulturowa obrazów............................................................ 204Przypisy .......................................................................................... 217Bibliografia ..................................................................................... 233Źródła fotografii ............................................................................. 243Indeks ............................................................................................. 2457

Przedmowa i podziękowaniaPewien chiński malarz bambusów miał usłyszeć od swojego kolegi, że drzewobambusowe powinno się studiować przez wiele dni, a malować przezkilka minut. Niniejszą książkę napisałem w stosunkowo krótkim czasie, leczpoczątki mojego zainteresowania prezentowanym w niej tematem sięgająprzeszło 30 lat wstecz. Badając wówczas narodziny pojęcia anachronizmuw kulturze europejskiej, zdałem sobie sprawę, że o ile teksty nie musząnasuwać pytania o to, czy przeszłość jest odległa w czasie, o tyle malarzeowej kwestii nie mogli pominąć i musieli zdecydować, czy – dajmy na to– Aleksandra Wielkiego sportretować w stroju epoki sobie współczesnej,czy też inaczej. Niestety, seria, w której został wówczas opublikowany mójtekst, nie była opatrzona ilustracjami.Od owego czasu miałem wiele sposobności do wykorzystywania obrazówjako świadectwa historycznego, a nawet prowadziłem na ten tematwykłady dla studentów pierwszego roku <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong> w Cambridge. Z tychzajęć, opracowanych i prowadzonych we współpracy z nieodżałowanej pamięciBobem Scribnerem, narodziła się niniejsza książka. Należy ona do serii,której Bob był współredaktorem. Mieliśmy nadzieję, że podobną pracęnapiszemy wspólnie. Dziś dedykuję ją jego pamięci.Pragnę podziękować mojej żonie Marii Lúcii, która uzmysłowiła miznaczenie określenia: „mój najlepszy krytyk”, Stephenowi Bannowi i RoyowiPorterowi za konstruktywne komentarze do pierwszej wersji niniejszejksiążki, a także José Garcíi Gonzálezowi za zwrócenie mojej uwagi na rozważaniaDiega de Saavedra Fajarda o jeździeckiej metaforze polityki.

Spis ilustracji1 Eugène Delacroix, szkic obrazu Kobiety algierskie, ok. 1832,akwarela ze śladami grafitu, Luwr, Paryż ....................................... 332 Constantin Guys, szkic akwarelowy przedstawiający sułtanaudającego się do meczetu, 1854, kolekcja prywatna ...................... 343 John White, Szkic wioski Secoton w stanie Wirginia, ok. 1585–1587,British Museum, Londyn ................................................................. 374 Robert Capa, Padający żołnierz, 1936, fotografia ............................ 425 Timothy O’Sullivan (negatyw) i Alexander Gardner (pozytyw),Żniwo śmierci, lipiec 1863, Gettysburg (A Harvest of Death,Gettysburg, July, 1863), plansza 36 ze Szkicownika Gardneraze zdjęciami z wojny (Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War),2 tomy (Washington, DC 1865–1866) ............................................ 436 Thomas Gainsborough, Pani Philip Thicknesse, z domu Anne Ford(Mrs. Philip Thicknesse, née Anne Ford), 1760, olej na płótnie,Cincinatti Art Museum .................................................................... 447 Joshua Reynolds, Lord Heathfield, gubernator Gibraltaru(Lord Heathfield, Governor of Gibraltar), 1787, olej na płótnie,National Gallery, Londyn ................................................................ 458 Joseph-Siffréde Duplessis, Ludwik XVI w szatach koronacyjnych(Louis XVI en costume de sacre), ok. 1770–1780, olej na płótnie,Musée Carnavalet, Paryż ................................................................ 479 François Girard, akwatinta według oficjalnego portretuLudwika Filipa pędzla Louisa Hersenta (oryginał wystawionyw 1831 roku, zniszczony w 1848 roku), Bibliothèque Nationalede France, Paryż ............................................................................. 4710 Detal ukazujący Merkurego i Gracje, Botticelli, Wiosna, ok. 1482,tempera na drewnie, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florencja ....................... 5611 Tycjan, Gwałt na Lukrecji, 1571, olej na płótnie, Fitzwilliam Museum,Cambridge ...................................................................................... 5712 Tycjan, Miłość niebiańska i miłość ziemska, 1514, olej na płótnie,Galleria Borghese, Rzym ................................................................. 5811

Naoczność13 Colin McCahon, Takaka – dzień i noc, 1948, olej na płótnienaklejonym na desce, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki,Nowa Zelandia ............................................................................... 6414 „Krucyfiks z Aaby”, druga połowa XI wieku, powlekane miedzią,rzeźbione, drewniane zaplecze ołtarza, Nationalmuseet,Kopenhaga ...................................................................................... 6915 Krucyfiks, 1304, drewno, Kościół Najświętszej Marii Pannyna Kapitolu, Kolonia ....................................................................... 6916 Wotum w imieniu syna rzeźnika, 14 marca 1853, olej na płótnie,Notre-Dame de Consolation, Hyères ............................................... 7117 Zdjęcie z Krzyża, XVI wiek, deska, San Giovanni Decollato, Rzym .... 7318 Lucas Cranach Starszy, para drzeworytów z Passional Christiund Antichristi (Wittenberga: J. Grunenberg, 1521) ....................... 7619 Hans Baldung Grien, „Luter jako mnich z aureolą i gołębicą”,detal z drzeworytu w: Acta et res gestae... in comitis principumWormaciae (Strasbourg: J. Schott, 1521), British Library, Londyn .... 7620 Eugène Delacroix, Wolność wiodąca lud na barykady, 1830–1831,olej na płótnie, Luwr, Paryż ............................................................ 8221 Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Statua Wolności, Nowy Jork,1884–1886 ...................................................................................... 8322 Chińska statua bogini demokracji, 1989, gips, Plac Tiananmen,Pekin (zniszczona).......................................................................... 8423 Diego Rivera, Cukrownia (1923), z cyklu fresków Kosmografiawspółczesnego Meksyku, 1923–1928. Ministerstwo Edukacji(Dziedziniec Pracy), Mexico City .................................................... 8524 Posąg cesarza Oktawiana Augusta (63 p.n.e.–14 n.e), kamień,Museo Gregoriano Profano, Rzym ................................................... 8725 Posąg cesarza Marka Aureliusza (121–180 n.e.), brąz, MuzeumKapitolińskie, Rzym ........................................................................ 8826 Nicolas Arnoult, rycina przedstawiająca (niezachowany do dziś)posąg Ludwika XIV dłuta Martina Desjardins, ok. 1686, niegdyśstojący na Place des Victoires w Paryżu .......................................... 8927 Jacques-Louis David, Cesarz Napoleon w swoim gabineciew Tuileries, 1812, olej na płótnie, National Gallery of Art,Washington, DC .............................................................................. 9028 Mussolini podczas biegu po plaży w Riccione, lata trzydziesteXX wieku, fotografia ....................................................................... 9129 Władimir Sierow, Chłopi z prośbą u Lenina, 1950, olej na płótnie,Galeria Trietiakowska, Moskwa ...................................................... 9212

Spis ilustracji30 Hubert Lanziger, Chorąży, lata trzydzieste XX wieku (?),olej na płótnie, US Army Art Collection, Washington, DC ............... 9431 Borys Karpow, Portret Stalina, 1949, olej na płótnie,lokalizacja nieznana ........................................................................ 9532 Richard Westmacott, Charles James Fox, 1810–1814, brąz,Bloomsbury Square, Londyn ........................................................... 9733 Jean-Baptiste Debret, Petit Moulin à Sucre portative (prasado wyciskania soku z trzciny cukrowej), akwatinta z Voyagepittoresque et historique au Brésil (Paryż, 1836–1839) .................... 10234 Rycina przedstawiająca zecernię w drukarni (Imprimerie),z „Receuil des planches” (1762), Encyclopédie (Paryż, 1751–1752) .... 10335 Vittore Carpaccio, Cud Krzyża Świętego na moście Rialto, ok. 1496,olej na płótnie, Galleria dell’Accademia, Wenecja ........................... 10536 Gerrit Adriaensz. Berckheyde, Zakole kanału Herengracht,Amsterdam, przed 1685 (?), rysunek lawowany tuszem chińskim,Gemeentearchief, Amsterdam ......................................................... 10637 Claude-Joseph Vernet, Port La Rochelle, 1763, olej na płótnie,Luwr, Paryż ..................................................................................... 10738 Pieter de Hooch, Podwórze domu w Delft, 1658, olej na płótnie,National Gallery, Londyn ................................................................ 10939 Jan Steen, Nieporządne domostwo, 1668, olej na płótnie,Apsley House (The Wellington Museum), Londyn .......................... 11140 Johannes De Witt, Szkic wnętrza teatru Swan, Londyn, ok. 1596,Biblioteka <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong> w Utrechcie .............................................. 11241 I.P. Hofmann, rycina przedstawiająca laboratoium chemiczneJustusa von Liebiga w Giessen, w: Das Chemiche Laboratoriumder Ludwigs-Universität zu Giessen (Heidelberg, 1842) .................... 11242 Vittore Carpaccio, Święty Augustyn w swojej pracowni, 1502–1508,olej i tempera na płótnie, Scuola di S. Giorgio degli Schiavoni,Wenecja .......................................................................................... 11343 Albrecht Dürer, Święty Hieronim w swojej pracowni, 1514, sztych ... 11444 G.M. Kraus (?), rycina przedstawiająca szezlong z pulpitemdo pisania do kompletu, w: „Journal des Luxus und des Moden”(1799) ............................................................................................ 11545 Włoska reklama mydła z lat pięćdziesiątych XX wieku ................... 11746 Fritz von Dardel, Pobudka w Orsie, 1893, rysunek lawowanyNordiska Museet, Sztokholm .......................................................... 11947 Pieter Jansz. Saenredam, Wnętrze kościoła świętego Bawonaw Haarlemie, 1648, olej na desce, National Gallery of Scotland,Edynburg ........................................................................................ 12013

Naoczność48 Widok wnętrza nowej i przestronnej księgarni John s. Jewett & Co.,Washington Street, numer 17, Boston, rycina w: „Gleason’s Pictorial”,2 grudnia 1854 ............................................................................... 12149 Giovanni Battista Bertoni, drzeworyt przedstawiający muzeumFrancesca Calzolariego, w: Benedetto Cerutti, Andrea Chiocco,Musaeum Francesci Calceolari Iunioris Veronensis (Werona, 1622) ..... 12250 J.H.W. Tischbein, szkic przedstawiający J.W. von Goethegopogrążonego w lekturze przy oknie swojego rzymskiego mieszkaniapodczas pierwszej podróży do Włoch, ok. 1787,Goethe-Nationalmuseum, Weimar .................................................. 12351 Joseph Wright („z Derby”), Sir Brooke Boothby czytający Rousseau,1781, olej na płótnie, Tate Britain, Londyn ..................................... 12352 William Hogarth, Dzieci Grahamów, 1742, olej na płótnie,National Gallery, Londyn ................................................................ 12853 Zhang Zeduan, detal scenki ulicznej w Kaifengu, w: Święto wiosnynad rzeką, ręczny zwój, początek XII wieku, tusz i kolor na jedwabiu,Muzeum Pałacowe, Pekin ............................................................... 13154 Torii Kiyomasu, Uliczna sprzedawczyni książek, ok. 1717,ręcznie barwiona odbitka drzeworytnicza ...................................... 13255 Miniatura z dzieła Akbarnāma ukazująca budynek Fatehpur Sikri,XVI wiek, Victoria & Albert Museum, Londyn ................................. 13356 Płaskorzeźba marmurowa przedstawiająca kobietę sprzedającąwarzywa, II/III wiek n.e., Museo Ostiense, Rzym ........................... 13557 Emmanuel de Witte, Sprzedawczyni drobiu na targu w Amsterdamie,olej na desce, Nationalmuseum, Sztokholm ................................... 13558 Greckie malowidło wazowe w stylu czerwonofigurowym autorstwa„malarza z Bolonii” (floruit 480–450 p.n.e.), ukazujące dwie młodedziewczyny, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nowy Jork .................... 13659 Dzieci, bądźcie grzeczne! Nicponi bowiem czeka straszliwa śmierć!,drzeworyt z wiejskiej szkoły, w: Nicolas-Edmé Rétif de la Bretonne,La Vie de mon père (Neufchâtel, Paryż, 1779) ................................. 13760 Abraham Bosse, Le Mariage à la Ville („Ślub w mieście”), 1633,drzeworyt, British Museum, Londyn ............................................... 13961 Louis Le Nain, Le repas des paysans („Chłopski posiłek”), 1642,olej na płótnie, Luwr, Paryż ............................................................ 14162 Mariamna Dawidowa, Piknik w lesie koło Kamienki, lata dwudziesteXX wieku, akwarela, lokalizacja nieznana ...................................... 14363 Dorothea Lange, Ubodzy zbieracze grochu w Kalifornii. Matkasiedmiorga dzieci. Wiek: 32 lata. Nipomo, Kalifornia. Luty, 1936 ..... 14414

Spis ilustracji64 Drzeworyt ukazujący tybetańskiego posła z „różańcem”,w: Jan Nieuhof, L’Ambassade de la Compagnie Orientale des ProvincesUnies vers l’Empereur de la Chine… (Leiden: J. de Meurs, 1665) ..... 14865 Wyspa i lud odkryte przez chrześcijańskiego króla Portugalii tudzieżjego poddanych, niemiecki drzeworyt ukazujący brazylijskich kanibali,ok. 1505, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich ................................ 15166 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Wielka odaliska, 1814,olej na płótnie, Luwr, Paryż ............................................................ 15367 Alberto Pasini, Scenka uliczna, Damaszek, olej na płótnie,Philadelphia Museum of Art ........................................................... 15468 Drzeworyt przedstawiający potwora, w: Wu Renchen,Shan-Hai-Jing. Guang. Zhu ............................................................. 15669 Pojemnik na proch strzelniczy z japońskim wyobrażeniemPortugalczyków, XVI wiek, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga,Lizbona ........................................................................................... 15770 Nigeryjska płyta brązowa wyobrażająca dwóch szesnastowiecznychPortugalczyków, zbiory prywatne ................................................... 15771 John Tenniel, Dwie siły, karykatura z „Puncha”,29 października 1881 ..................................................................... 15872 Drzeworyt wyobrażający wiedźmę, początek XIX wieku ................. 16173 Pieter Breughel Starszy, Wesele chłopskie, ok. 1566, olej na płótnie,Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń ................................................ 16274 William Edward Kilburn, Wielki wiec czartystów na KenningtonCommon, 10 kwietnia 1848, dagerotyp, Windsor Castle, Berks ...... 16575 Gerard ter Borch, Złożenie przysięgi ratyfikacji pokoju westfalskiego15 maja 1648 roku, 1648, olej na miedzi, National Gallery,Londyn ........................................................................................... 16676 Récit Memorable du Siège de la Bastille, drzeworyt barwny,Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paryż ........................................ 17077 Huỳnh Công Út, Atak napalmem, 1972, fotografia ......................... 17578 Detal ukazujący śmierć króla Harolda w bitwie pod Hastings,tkanina z Bayeux, ok. 1100, Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux .......... 17979 Fotos z filmu Gilla Pontecorva Bitwa o Algier (1966)...................... 19180 Plakat filmu Bernarda Bertolucciego Wiek XX (Novecento) (1976).... 19981 Jacob Ochtervelt, Uliczni muzycy w progu domostwa, 1665,olej na płótnie, The Art Museum, St. Louis Art Museum ................. 21382 Augusto Stahl, Rua da Floresta, Rio de Janeiro, ok. 1865,druk techniką białkową, kolekcja prywatna .................................... 21515

PrzypisyWprowadzenie do wydania polskiego: „Przesłuchując naocznego świadka”1Niniejszy esej po raz pierwszy ukazał się w tłumaczeniu hiszpańskim: Cómo interrogara los testimonios visuales, [w:] Joan Lluís Palos, Diana Carrió-Invernizzi (red.), La historiaimaginada: construcciones visuales del passado en la Edad Moderna (Barcelona, CEEH2008), s. 29–40. Wstępne wersje tekstu były prezentowane jako wykłady i prace seminaryjnew Barcelonie, na Uniwersytecie Cambridge (Gonville College i Caius College), w KrusenbergHerrgaard (Szwecja), w Londynie (Tate Britain), w College Park <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong> Stanu Marylandoraz na Uniwersytecie w Uppsali.2Jonathan Brown, John Elliott, A Palace for a King (New Haven, CT, London 1980).3Serge Gruzinski, La guerre des images (Paris 1990); Peter Burke, The Fabrication of LouisXIV (New Haven, CT, London 1992).4Ivan Gaskell, Visual History, [w:] Peter Burke (red.), New Perspectives on Historical Writing,wydanie drugie (Cambridge 2001), s. 187–217.5Frederick J. Duparc, Carel Fabritius (The Hague 2004).6W ostatnim czasie w języku szwedzkim ukazały się dwa omówienia tego zagadnienia:Lars M. Andersson, Lars Berggren, Ulf Zander (red.), Mer än tusen ord: Bilden och dehistoriska vetenskaperna (Lund 2001); Reine Rydén, Hur skall vi använda bilder?, „HistoriskTidskrift”, 126 (2006), s. 491–500.7James Elkins, Visual Culture: A Sceptical Introduction (London 2003); Richard Howells,Visual Culture (Cambridge 2003).8Adolfo Mignemi, Lo sguardo e l’immagine: La fotografia come documento storico (Turin2003); Christian Delage, Vincent Guigueno, L’historien et le film (Paris 2004); Tommy Gustafsson,Filmen som historisk källa, „Historisk Tidskrift”, 126 (2006), s. 471–490.9Christian Delage, L’image comme prevue: L’expérience du procès de Nuremberg, „VingtièmeSiècle”, 72 (2000), s. 63–78; tenże, La vérité par l’image: De Nuremberg au process Milošević(Paris 2006).10„Estado de São Paulo” opisał wideo z 21 marca 2006 roku ukazujące naczelnika więzieniaprzyjmującego 20 tysięcy reali (9 sierpnia 2006), s. C8.11Praca Piyel Haldar, Law and the Evidential Image, „Law Culture and the Humanities”,4 (2008), s. 139–155, omawia ten przykład, by zilustrować, jak prawnicy badają obrazyw sądzie.12Jennifer Tucker, Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science (Baltimore,MD 2006).13Boris Kossoy, Realidades e Ficções na trama fotográfica (São Paulo 1999), s. 29. Haldar,‘Law’, opisuje, jak prawnicy mogą wykorzystywać stop-klatki z materiałów wideo.14Kossoy, Realidades, s. 54; por. Philippe Dubois, El acto fotográfico, de la representacióna la recepción (Barcelona 1986).15Peter Burke, The Renaissance, Individualism and the Portrait, „History of EuropeanIdeas”, 21 (1995), s. 393–400.16Peter Burke, The Sense of Anachronism from Petrarch to Poussin, [w:] Chris Humphrey,W.M. Ormrod (red.), Time in the Medieval World (Woodbridge, Wielka Brytania 2001),s. 157–173.217

Naoczność17Cynthia Hahn, Interpictoriality in the Limoges Chasses, [w:] Colum Hourihane (red.),Image and Belief (Princeton, NJ 1999), s. 109–124; taż, Portrayed on the Heart (Berkeley, CA2001); William Johnstone, Interpictoriality: The Lives of Moses and Jesus in the Murals of theSistine Chapel, [w:] A.G. Hunter, P.R. Davies (red.), Sense and Sensitivity (Sheffield 2002),s. 416–455.18Werner Busch, Nachahmung als bürgerliches Kunstprinzip: Ikonographische Zitate beiHogarth (Hildesheim, New York 1977); M. Rohlmann, Zitate flämischer Landschaftmotivein Florentiner Quattrocentomalerei, [w:] J. Poeschke (red.), Italienische Frührenaissance undnordeuropäisches Spätmittelalter (Munich 1993), s. 235–258.19Margaret A. Rose, Parodie, Intertextualität, Interbildlichkeit (Bielefeld 2006).20Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford 1972);Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century(Cambridge, MA 1991); James A.W. Hefferman, Cultivating Picturacy: Visual Art and VerbalInterventions (Waco 2006). W tym miejscu pragnę podziękować Fernandowi Maríasowi zazwrócenie mojej uwagi na pracę Crary’ego o „reżimach wizualnych”. Tego terminu wcześniejużywał Christian Metz, a nieco później Martin Jay, Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Visionin Twentieth-Century French Thought (Berkeley, CA 1993).21Gruzinski, La guerre; James F. Cahill, The Compelling Image: Nature and Style in Seventeenth-CenturyChinese Painting (Cambridge, MA 1982).22Delage, Guigueno, L’historien, s. 139 i nast.23Sergiu Celac, tłumacz ustny, cyt. w: John Sweeney, The Life and Evil Times of NicolaeCeauşescu (London 1991), s. 125. Zob. ogólne omówienie: Laurent Gervereau, Une siècle demanipulations par l’image (Paris 2000).24Zob. doniesienia brytyjskiej prasy z maja 2004 roku.25Luis Diéz del Corral, Velázquez, la Monarchia y Italia (Madrid 1979), s. 141.26Gianfranco Contini, Varianti e altra linguistica (Turin 1970).27Richard Kagan (red.), Spanish Cities of the Golden Age: The Views of Anton van den Wyngaerde(Berkeley, CA 1989); Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World 1493–1793(New Haven, CT, London 2000), s. 13–14, 200.28Börje Magnusson, Sweden Illustrated: Erik Dahlbergh’s Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna asa Manifestation of Imperial Ambition, [w:] Allan Ellenius (red.), Baroque Dreams: Art andCultural and Social History Vision in the Era of Greatness (Uppsala 2003), s. 35–39.29Cesare de Seta, Massimo Ferretti, Alberto Tenenti, Città d’Europa: Iconografia e vedutismodal xv al xix secolo (Naples 1996); Wolfgang Behringer, Bernd Roeck (red.), Das Bild derStadt in der Neuzeit, 1400–1800 (Munich 1999).30Gottfried Boehm, Bildnis und Individuum: Über den Ursprung der Porträtmalerei (Munich1985); Peter Burke, The Renaissance, Individualism and the Portrait, „History of EuropeanIdeas”, 21 (1995), s. 393–400.31Klaske Muizelaar, Derek L. Phillips, Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age(New Haven, CT, London 2003), s. 54, 59.32Diego Gambetta, La mafia siciliana (Turin 1992).33Friedrich Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa (Stanford, CA 1998), s. 324–326.Wprowadzenie: świadectwo obrazów1Gordon Fyfe, John Law, On the Invisibility of the Visual, [w:] tychże (red.), PicturingPower (London 1988), s. 1–14; Roy Porter, Seeing the Past, „Past and Present”, CXVIII (1988),s. 186–205; Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence (1990: przekład ang. London 1994), s. 3;Ivan Gaskell, Visual History, [w:] Peter Burke (red.), New Perspectives on Historical Writing(1991: wyd. drugie, Cambridge 2000), s. 187–217; Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual andRepresentation (London 1996), s. 7.218

Przypisy2Raphael Samuel, The Eye of History, [w:] tegoż, Theatres of Memory, tom I (London1994), s. 315–336.3David C. Douglas, G.W. Greenaway (red.), English Historical Documents, 1042–1189(London 1953), s. 247.4Francis Haskell, History and its Images (New Haven 1993), s. 123–124, 138–144; krytykten został przywołany w: Léon Lagrange, Les Vernet et la peinture au 18e siècle (wyd.drugie, Paris 1864), s. 77.5Haskell, History, s. 9, 309, 335–346, 475, 482–494; Burckhardt cyt. w: Lionel Gossman,Basel in the Age of Burckhardt (Chicago 2000), s. 361–362; na temat Huizingi por. ChristophStrupp, Johan Huizinga: Geschichtswissenschaft als Kulturgeschichte (Göttingen 1999), szczególnies. 67–74, 116, 226.6Frances A. Yates, Shakespeare’s Last Plays (London 1975), s. 4; por. tenże, Ideas andIdeals in the North European Renaissance (London 1984), s. 312–315, 321.7Robert M. Levine, Images of History: 19 th and Early 20 th Century Latin American Photographsas Documents (Durham, NC 1989).8Philippe Ariès, Un historien de dimanche (Paris 1980), s. 122; por. Michel Vovelle (red.),Iconographie et histoire des mentalités (Aix 1979); Maurice Agulhon, Marianne into Battle: RepublicanImagery and Symbolism in France, 1789–1880 (1979: tłumaczenie ang. Cambridge1981).9William J.T. Mitchell (red.), Art and the Public Sphere (Chicago 1992), wprowadzenie.10Robert I. Rotberg, Theodore K. Rabb (red.), Art and History: Images and their Meanings(Cambridge 1988).11Gustaaf J. Renier, History, its Purpose and Method (London 1950).12Haskell, History, s. 7; Stephen Bann, Face-to-Face with History, „New Literary History”,XXIX (1998), s. 235–246.13John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories(Amherst 1988), s. 66–102; Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images asHistory, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York 1989), s. 28–29.14Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting (2 tomy, Cambridge, MA 1953); por.Linda Seidel, Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait: Stories of an Icon (Cambridge 1993); ErnstH. Gombrich, The Image and the Eye (London 1982), s. 253.15Patricia F. Brown, Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio (New Haven1988), s. 5, 125.16Na temat tekstów zob. Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy (Toronto 1962); por.Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (2 tomy, Cambridge 1979).Odnośnie do obrazów wizualnych zob. William H. Ivins, Jr, Prints and Visual Communication(Cambridge, MA 1953); por. David Landau, Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print 1470–1550(New Haven 1994), s. 239.17Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936: tłumaczenieang. w: Illuminations [London 1968], s. 219–244; por. Michael Camille, The TrèsRiches Heures: An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, „CriticalInquiry”, XVII (1990–1991), s. 72–107.18Edward H. Carr, What is History? (Cambridge 1961), s. 17. Wyd. pol.: Historia – czymjest? Wykłady im. George’a Macaulaya Trevelyana wygłoszone na uniwersytecie w Cambridgestyczeń–marzec 1961, tłum. Piotr Kuś, Poznań 1999.1. Fotografie i portrety1Francis, cyt. w: James Borchert, Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religionand Folklife in an American City (Urbana 1980), s. 271; Roland Barthes, The Reality Effect(1968: tłumaczenie ang. w: The Rustle of Language, Oxford 1986, s. 141–148).219

Naoczność2Roy E. Stryker, Paul H. Johnstone, Documentary Photographs, [w:] Caroline Ware(red.), The Cultural Approach to History (New York 1940), s. 324–330; F. J. Hurley, Portrait ofa Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography (London 1972); MarenStange, Symbols of Social Life: Social Documentary Photography in America, 1890–1950(Cambridge 1989); Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History,Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York 1989), s. 190–192.3John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Amherst1988), s. 117–152; Stange, Symbols, s. 2, 10, 14–15, 18–19; Sarah Graham-Brown, Palestiniansand their Society, 1880–1946: A Photographic Essay (London 1980), s. 2.4Siegfried Kracauer, History: The Last Things before the Last (New York 1969), s. 51–52;por. Dagmar Barnouw, Critical Realism: History, Photography and the Work of Siegfried Kracauer(Baltimore 1994); Stryker, Johnstone, Photographs.5Raphael Samuel, The Eye of History, [w:] tegoż, Theatres of Memory, tom I (London1994), s. 315–336, na s. 319.6Trachtenberg, Reading, s. 71–118, 164–230; Caroline Brothers, War and Photography:A Cultural History (London 1997), s. 178–185; Michael Griffin, The Great War Photographs,[w:] B. Brennen, H. Hardt (red.), Picturing the Past (Urbana 1999), s. 122–157, s. 137–138;Tagg, The Burden, s. 65.7Paul Thompson, Gina Harkell, The Edwardians in Photographs (London 1979), s. 12;John Ruskin, The Cestus of Aglaia (1865–1866: wznowienie w: tegoż: Works, vol. XIX [London1905], s. 150); M.D. Knowles, Air Photography and History, [w:] J.K.S.St. Joseph (red.),The Uses of Air Photography (Cambridge 1966), s. 127–137.8David Smith, Courtesy and its Discontents, „Oud-Holland” C (1986), s. 2–34; PeterBurke, The Presentation of Self in the Renaissance Portrait, [w:] tegoż, Historical Anthropologyof Early Modern Italy (Cambridge 1987), s. 150–167; Richard Brilliant, Portraiture (London1991).9Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York 1958); przykładyangielskie zaczerpnięto z: Desmond Shawe-Taylor, The Georgians: Eighteenth-Century Portraitureand Society (London 1990).10Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning and Effect (New York 1981), s. 70.11Michael Marrinan, Painting Politics for Louis Philippe (New Haven 1988), s. 3.12J. Brian Harley, Deconstructing the Map (1989: wznowienie w: T.J. Barnes, James Duncan(red.), Writing Worlds [London 1992], s. 231–247). Por. Jürgen Schulz, Jacopo Barbari’sView of Venice: Map Making, City Views and Moralized Geography, „Art Bulletin”, LX (1978),s. 425–474.13Ruth B. Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passages of Western Art and Literature (New Haven2000).14Jan Bialostocki, The Image of the Defeated Leader in Romantic Art (1983: wznowieniew tegoż: The Message of Images (Vienna 1988), s. 219–233 [wyd. pol. Jan Białostocki Pokonanybohater w sztuce romantyzmu, „Twórczość” 1980, t. 36, nr 11 (przyp. tłum.)]; ArnoldHauser, The Social History of Art (2 tomy, London 1951) [wyd. pol. Arnold Hauser, Społecznahistoria sztuki i literatury, tłum. Janina Ruszczycówna, posłowie Juliusz Starzyński, Warszawa1974 (przyp. tłum.)]; por. krytykę autorstwa Ernesta H. Gombricha, The Social History ofArt (1953; wznowienie w Meditations on a Hobby Horse [London 1963], s. 86–94).15Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World (London 1983), s. 102.16Carlo Ginzburg, Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm (1978: wznowienie w tegoż:Myths, Emblems, Clues [London 1990], s. 96–125).17Ivan Lermolieff (Giovanni Morelli), Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei(3 tomy, Leipzig 1890–1893), szczególnie tom I, s. 95–99; por. Hauser, Social History, s. 109–110, oraz Ginzburg, Clues, s. 101–102; Aby Warburg, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity (1932:tłumaczenie ang. Los Angeles 1999).18Siegfried Kracauer, History of the German Film (1942: wznowienie w tegoż: Briefwechsel(red.) V. Breidecker [Berlin 1996], s. 15–18).220

Przypisy2. Ikonografia i ikonologia1Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting (2 tomy, Cambridge, MA 1953); Eddy deJongh Realism and Seeming Realism in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting, (1971: tłumaczenieang. w: Wayne Franits (red.), Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered[Cambridge 1997], s. 21–56); tenże, The Iconological Approach to Seventeenth-CenturyDutch Painting, [w:] Franz Grijzenhout, Henk van Veen (red.), The Golden Age of Dutch Paintingin Historical Perspective (1992: tłumaczenie ang. Cambridge 1999), s. 200–223.2Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology (New York 1939), s. 3–31.3Ernest H. Gombrich, Aims and Limits of Iconology, [w:] tegoż, Symbolic Images (London1972), s. 1–25, szczególnie s. 6; de Jongh, Approach. Por. Robert Klein, Considérations surles fondements de l’iconographie (1963: wznowienie w: La Forme et l’intelligible [Paris 1970],s. 353–374).4Panofsky, Iconology, s. 150–155; Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance (1958:wydanie drugie Oxford 1980), s. 121–128.5Aby Warburg, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity (1932: tłumaczenie ang. Los Angeles,1999), s. 112–115.6Charles Hope, Artists, Patrons and Advisers in the Italian Renaissance, [w:] Guy F. Lytle,Stephen Orgel (red.), Patronage in the Renaissance (Princeton 1981), s. 293–343.7Ernest H. Gombrich, In Search of Cultural History (Oxford 1969); K. Bruce McFarlane,Hans Memling (Oxford 1971).8Ronald Paulson, Emblem and Expression (London 1975); Denis Cosgrove, Stephen Daniels(red.), The Iconography of Landscape (Cambridge 1988).9Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London 1995).10Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting 1825–1875(1980: wydanie poprawione, New York 1995).11R. Etlin (red.), Nationalism in the Visual Arts (London 1991); Jonas Frykman, OrvarLöfgren, Culture Builders: A Historical Anthropology of Middle-Class Life (1979: tłumaczenieang. New Brunswick 1987), s. 57–58; Albert Boime, The Unveiling of the National Icons(Cambridge 1994).12David Matless, Landscape and Englishness (London 1998).13Hugh Prince, Art and Agrarian Change, 1710–1815, [w:] Cosgrove, Daniels, Iconography,s. 98–118.14Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World (London 1983); Ann Bermingham, Landscapeand Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740–1860 (London 1986).15Stephen Daniels, The Political Iconography of Landscape, [w:] Cosgrove, Daniels, Iconography,s. 43–82; Martin Warnke, Political Landscape: The Art History of Nature (1992:tłumaczenie ang. London 1994), s. 75–83; Schama, Landscape.16Novak, Nature, s. 189; Nicholas Thomas, Possessions: Indigenous Art and Colonial Culture(London 1999), s. 20–23.3. Święte i nadprzyrodzone1Jean Wirth, L’image médiévale: Naissance et développement (Paris 1989); Françoise Dunand,Jean-Michel Spieser, Jean Wirth (red.), L’image et la production du sacré (Paris 1991).2Jean-Claude Schmitt, Ghosts in the Middle Ages (1994: tłumaczenie ang. Chicago 1998),s. 241; Luther Link, The Devil: A Mask without a Face (London 1995); Robert Muchembled,Une histoire du diable (12 e –20 e siècles) (Paris 2000).3Gaby Vovelle, Michel Vovelle, Vision de la mort et de l’au-delà en Provence (Paris 1970),s. 61.4Heinrich Zimmer, Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilisation (1946: wydanie drugie,New York 1962), s. 151–155; Partha Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters: History of EuropeanReactions to Indian Art (Oxford 1977).221

Naoczność5Lawrence G. Duggan, Was Art really the Book of the Illiterate”?, „Word and Image”V (1989), s. 227–251; Danièle Alexandre-Bidon, Images et objets de faire croire, „Annales:Histoire, sciences sociales”, LIII (1998), s. 1155–1190.6Emile Mâle, L’art religieux de la fin du Moyen Age en France (Paris 1908); tenże, L’artreligieux de la fin du seizième siècle: Etude sur l’iconographie après le concile de Trente (Paris1932); Richard W. Southern, The Making of the Middle Ages (London 1954); Mitchell B. Merback,The Thief, the Cross and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval andRenaissance Europe (London 1999).7Richard Trexler, Florentine Religious Experience: The Sacred Image, „Studies in the Renaissance”,XIX (1972), s. 7–41.8Bernard Cousin, Le Miracle et le Quotidien: Les ex-voto provençaux images d’une société(Aix 1983); David Freedberg, The Power of Images (Chicago 1989), s. 136–160.9Sixten Ringbom, From Icon to Narrative (Åbo 1965); Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence(1990: tłumaczenie ang. 1994), s. 409–457.10Freedberg, Power, s. 192–201; por. Merback, Thief, 41–46.11Samuel Y. Edgerton, Pictures and Punishment: Art and Criminal Prosecution during theFlorentine Renaissance (Ithaca 1985).12Mâle, Moyen âge, s. 28–34; Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford 1972), s. 41.13Mâle, Trente; Freedberg, Power.14Millard Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death (Princeton 1951),s. 117, 121; Frederick P. Pickering, Literature and Art in the Middle Ages (1970), s. 280.15Mâle, Trente, s. 151–155, 161–162.16James Billington, The Icon and the Axe (New York 1966), s. 158.17Walter Abell, The Collective Dream in Art (Cambridge, MA 1957); Link, Devil, s. 180.18Abell, Dream, s. 121, 127, 130, 194; Jean Delumeau, La peur en occident (Paris 1978);W.G. Naphy, P. Roberts (red.), Fear in early modern society (Manchester 1997).19Freedberg. Power; Serge Gruzinski, La guerre des images (Paris 1990); Olivier Christin,Une révolution symbolique: L’iconoclasme huguenot et la reconstruction catholique (Paris 1991).20Robert W. Scribner, For the Sake of Simple Folk (1981: wydanie drugie, Oxford 1995),s. 244.21Mikhail Bakhtin, The World of Rabelais (1965: tłumaczenie ang. Cambridge, MA1968); Scribner, Folk, s. 62, 81.22Scribner, Folk, s. 149–163.23Tamże, s. 18–22.24Belting, Likeness, s. 14, 458–490; Patrick Collinson, From Iconoclasm to Iconophobia:The Cultural Impact of the Second Reformation (Reading 1986).25Collinson, Iconoclasm, s. 8.26Mâle, Trente.4. Władza i protest1André Grabar, Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton 1968), s. 78–79;Jas Elsner, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire, AD 100–450(Oxford 1998).2Frances A. Yates, Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century (London 1975),s. 78, 101, 109–110.3Peter Burke, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (New Haven 1992), s. 9.4Toby Clark, Art and Propaganda in the 20 th Century: The Political Image in the Age ofMass Culture (London 1977); Zbynek Zeman, Selling the War: Art and Propaganda in World222

BibliografiaAbell, Walter, The Collective Dream in Art (Cambridge, MA 1957).Ades, Dawn i in. (red.), Art and Power (London 1996).Agulhon, Maurice, Marianne into Battle: Republican Imagery and Symbolism in France,1789–1880 (1979: tłumaczenie ang. Cambridge 1981).Aldgate, Anthony, British Newsreels and the Spanish Civil War, „History”, LVIII (1976),s. 60–63.——, Cinema and History: British Newsreels and the Spanish Civil War (London 1979).Alexandre-Bidon, Danièle, Images et objets de faire croire, „Annales Histoire SciencesSociales”, LIII (1998), s. 1155–1590.Alpers, Svetlana, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (Chicago,1983).——, Interpretation without Representation, „Representations”, I (1983), s. 30–42.——, Realism as a comic mode: Low-life painting seen through Bredero’s eyes, „Simiolus”VIII (1975–1956), s. 115–139.Anderson, Patricia, The Printed Image and the Transformation of Popular Culture,1790–1860 (Oxford, 1991).Ariès, Philippe, Centuries of Childhood (1960: tłumaczenie ang. London 1965).——, The Hour of Our Death (1977: tłumaczenie ang. London 1981).——, Un historien de Dimanche (Paris 1980).——, Images of Man and Death (1983: tłumaczenie ang. Cambridge, MA 1985).Armstrong, C.M., Edgar Degas and the Representation of the Female Body, [w:] S.R. Suleiman(red.), The Female Body in Western Culture (New York 1986).Atherton, Herbert M., Political Prints in the Age of Hogarth: A Study of the IdeographicRepresentation of Politics (Oxford 1974).Baker, Steve, The Hell of Connotation, „Word and Image”, I (1985), s. 164–175.Bann, Stephen, Face-to-Face with History, „New Literary History”, XXIX (1998),s. 235–246.——, Historical Narrative and the Cinematic Image, „History & Theory. Beiheft”, XXVI(1987), s. 47–67.Barnouw, Dagmar, Critical Realism: History, Photography and the Work of SiegfriedKracauer (Baltimore 1994).Barnouw, Eric, Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film (New York 1974).Barrell, John, The Dark Side of the Landscape (Cambridge 1980).Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida (1980: tłumaczenie ang. London 1981).——, Image, Music, Text, Stephen Heath (red.), (New York 1977), s. 32–51.——, Mythologies (1957: tłumaczenie ang. London 1972).——, The Reality Effect (1968: tłumaczenie ang. w: Barthes, The Rustle of Language,Oxford 1986), s. 141–148.Baxandall, Michael, Limewood Sculptors in Renaissance Germany (New Haven 1980).——, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford 1972).233

NaocznośćBelting, Hans, Likeness and Presence (1990: tłumaczenie ang. London 1994).Benjamin, Walter, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936:tłumaczenie ang. w Illuminations, London 1968), s. 219–244.Berggren, Lars, Lennart Sjöstedt, L’ombra dei grandi: Monumenti e politica monumentalea Roma (1870–1895) (Rome 1996).Bermingham, Ann, Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740–1860(London 1986).Bialostocki, Jan, The Image of the Defeated Leader in Romantic Art (1983: wznowieniew: Bialostocki, The Message of Images, Vienna 1988), s. 219–233.Binski, Paul, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (London 1996).Blunt, Antony, Poussin (2 tomy, London 1967).Boime, Albert, The Unveiling of the National Icons (Cambridge 1994).Bondanella, Peter, The Films of Roberto Rossellini (Cambridge 1993).Borchert, James, Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religion and Folklifein an American City (Urbana 1980).——, Historical Photo-Analysis: A Research Method, „Historical Methods”, XV (1982),s. 35–44.Bredekamp, Horst, Florentiner Fussball: Renaissance der Spiele (Frankfurt 1993).Brettell, Richard R., Caroline B. Brettell, Painters and Peasants in the Nineteenth Century(Geneva 1983).Brilliant, Richard, The Bayeux Tapestry, „Word and Image”, VII (1991), s. 98–126.——, Portraiture (London 1991).——, Visual Narratives: Storytelling in Etruscan and Roman Art (Ithaca 1983).Brothers, Caroline, War and Photography: A Cultural History (London 1997).Brown, Patricia F., Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio (New Haven1988).Brubaker, Leslie, The Sacred Image, [w:] Robert Ousterhout, L. Brubaker (red.) The SacredImage. East and West (Urbana and Chicago 1995), s. 1–24.Brunette, Peter, Roberto Rossellini (New York 1987).Bryson, Norman, Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze (London 1983).Bucher, Bernadette, Icon and Conquest: A Structural Analysis of the Illustrationsof de Bry’s Great Voyages (1977: tłumaczenie ang. Chicago 1981).Burke, Peter, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (New Haven 1992).Cameron, Averil, The Language of Images: The Rise of Icons and Christian Representation,[w:] Diana Wood (red.), The Church and the Arts (Oxford 1992), s. 1–42.Camille, Michael, Mirror in Parchment: The Luttrell Psalter and the Making of MedievalEngland (London 1998).——, The Très Riches Heures: An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,„Critical Inquiry”, XVII (1990–1991), s. 72–107.Carteras, S.P., Images of Victorian Womanhood in English Art (London 1987).Cassidy, Brendan (red.), Iconography at the Cross-Roads (Princeton 1993).Cederlöf, Olle, The Battle Painting as a Historical Source, „Revue Internationale d’HistoireMilitaire”, XXVI (1967), s. 119–144.Christin, Olivier, Une révolution symbolique: L’iconoclasme huguenot et la reconstructioncatholique (Paris 1991).Clark, Timothy J., The Absolute Bourgeois: Art and Politics in France, 1848–1851 (London1973).——, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (London 1973).234

Bibliografia——, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers (New Haven1985).Clark, Toby, Art and Propaganda in the 20 th Century: The Political Image in the Ageof Mass Culture (London 1977).Clayson, Hollis, Painted Love: Prostitution in French Art of the Impressionist Era (NewHaven 1991).Collinson, Patrick, From Iconoclasm to Iconophobia: The Cultural Impact of the SecondReformation (Reading 1986).Comment, Bernard, The Panorama (1993: tłumaczenie ang. London 1999).Cosgrove, Denis, Stephen Daniels (red.), The Iconography of Landscape (Cambridge1988).Coupe, William A., The German Illustrated Broadsheet in the Seventeenth Century (2 tomy,Baden-Baden 1966).Cousin, Bernard, Le Miracle et le Quotidien: Les ex-voto provençaux images d’une société(Aix 1983).Curtis, L. Perry jr, Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature (Newton Abbot1971).Davidson, Jane P., David Teniers the Younger (London 1980).——, The Witch in Northern European Art (London 1987).Davis, Natalie Z., Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision (Toronto 2000).Desser, David, The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa (Ann Arbor 1983).Dillenberger, John, Images and Relics: Theological Perception and Visual Images in Sixteenth-CenturyEurope (New York 1999).Dowd, D.L., Pageant-Master of the Republic: Jacques-Louis David and the French Revolution(Lincoln, NE 1948).Duffy, Eamon, The Stripping of the Altars (New Haven 1992).Durantini, Mary Frances, The Child in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting (Ann Arbor1983).Eco, Umberto, La struttura assente: Introduzione alla ricerca semiologica (Milan 1968).Edgerton, Samuel Y., Pictures and Punishment: Art and Criminal Prosecution during theFlorentine Renaissance (Ithaca 1985).Elsner, Jas, Art and the Roman Viewer (Cambridge 1995).——, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire, AD 100–450(Oxford 1998).Etlin, R. (red.), Nationalism in the Visual Arts (London 1991).Ferro, Marc, Cinema and History (tłumaczenie ang. London 1988).Forsyth, Ilene H., Children in Early Medieval Art: Ninth through Twelfth Centuries, „Journalof Psychohistory”, IV (1976), s. 31–70.Foucault, Michel, The Order of Things (1966: tłumaczenie ang. London 1970).Fox, Celina, The Development of Social Reportage in English Periodical Illustration duringthe 1840s and Early 1850s, „Past & Present”, LXXIV (1977), s. 90–111.Franits, Wayne (red.), Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered(Cambridge 1997).——, Paragons of Virtue (Cambridge 1993).Freedberg, David, The Power of Images (Chicago 1989).Fried, Michael, Absorbtion and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot(Berkeley and Los Angeles 1980).Friedman, John B., The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge, MA1981).235

NaocznośćGamboni, Dario, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution(London 1997).Garton Ash, Timothy, The Life of Death (1985: wznowienie w: Timothy Garton Ash,The Uses of Adversity, wydanie drugie: Harmondsworth 1999), s. 109–129.Gaskell, Ivan, Tobacco, Social Deviance and Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (1987:wznowienie w: Franits, 1997), s. 68–77.——, Visual History, [w:] Peter Burke (red.), New Perspectives on Historical Writing,(1991: wydanie drugie, Cambridge 2000), s. 187–217.George, M. Dorothy, English Political Caricature: A Study of Opinion and Propaganda(2 tomy, Oxford 1959).Gilman, Sander L., Health and Illness: Images of Difference (London 1995).——, The Jew’s Body (New York 1991).Ginzburg, Carlo, Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm (1978: wznowienie w: C. Ginzburg,Myths, Emblems, Clues [London 1990]), s. 96–125.Goffman, Erving, Gender Advertisements (London 1976).Golomstock, Igor, Totalitarian Art: In the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy andthe People’s Republic of China (London 1990).Gombrich, Ernst H., Aims and Limits of Iconology, [w:] Symbolic Images (London 1972),s. 1–25.——, The Image and the Eye (London 1982).——, Personification, [w:] Robert R. Bolgar (red.), Classical Influences on European Culture,(Cambridge 1971), s. 247–257.——, In Search of Cultural History (Oxford 1969).——, The Social History of Art (1953: wznowienie w: E. Gombrich, Meditations ona Hobby Horse [London 1963]), s. 86–94.Grabar, André, Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton 1968).Graham-Brown, Sarah, Images of Women: Photography of the Middle East, 1860–1950(London 1988).——, Palestinians and their Society, 1880–1946: A Photographic Essay (London 1980).Grenville, John, The Historian as Film-Maker, [w:] Paul Smith (red.), The Historian andFilm (London 1976), s. 132–141.Grew, Raymond, Picturing the People, [w:] Robert I. Rotberg, Theodore K. Rabb (red.),Art and History: Images and Their Meanings (Cambridge 1988), s. 203–231.Gruzinski, Serge, La guerre des images (Paris 1990).Gudlaugsson, S. J., De comedianten bij Jan Steen en zijn Tijdgenooten (The Hague 1945).Hale, John R., Artists and Warfare in the Renaissance (New Haven 1990).Harley, J.B., Deconstructing the Map (1989: wznowienie w: T.J. Barnes, James Duncan(red.), Writing Worlds [London 1992]), s. 231–247.Harris, Enriqueta, Velázquez’s Portrait of Prince Baltasar Carlos in the Riding School,„Burlington Magazine”, CXVIII (1976), s. 266–275.Haskell, Francis, History and its Images (New Haven 1993).——, The Manufacture of the Past in Nineteenth-Century Painting, „Past and Present”, LIII(1971), s. 109–120.Hassig, Debra, The Iconography of Rejection: Jews and Other Monstrous Races, [w:]Colum Hourihane (red.), Image and Belief (Princeton 1999), s. 25–37.Hauser, Arnold, The Social History of Art (2 tomy, London 1951).Held, Jutta, Monument und Volk: Vorrevolutionäre Wahrnehmung in Bildern des ausgehendenAncien Regime (Cologne–Vienna 1990).Herbert, Robert L., Impressionism: Art, Leisure and Parisian Society (New Haven 1988).236

IndeksAckermann Rudolph (1764–1834), rytownikniemiecki 104Aldgate Anthony, historyk brytyjski 186,229Alpers Svetlana (1936–), amerykańska historyksztuki 105, 224, 227, 230Antal Frederick (1887–1954), węgierskihistoryk sztuki 204Ariès Philippe (1914–1984), historyk francuski30, 127–130, 137, 219, 225Asch Timothy (1932–1994), amerykańskireżyser filmowy 193Ast Friedrich (1778–1841), niemiecki filologklasyczny 55Bachofen Johann Jakob (1815–1887), filologszwajcarski 196Bachtin Michaił (1895–1975), rosyjski teoretykkultury 75Bann Stephen (1942–), angielski krytyki historyk 9, 32, 210, 219, 229, 231Barbari Jacopo de (zm. ok. 1516), artystawenecki 49Bargrave John (1610–1680), kanonik katedryw Canterbury 206, 231Barker Henry Aston (1774–1856), malarzbrytyjski 172Barker Robert (1739–1806), malarz brytyjski172Barthes Roland (1915–1980), semiotykfrancuski 40, 54, 116, 195, 198, 201,205, 219, 230Bartholdi Frédéric Auguste (1834–1904),rzeźbiarz francuski 83Baxandall Michael (1933–2008), brytyjskihistoryk sztuki 22, 25, 206, 218,222, 231Bayeux zob. tkanina z BayeuxBellotto Bernardo (1721–1780), malarzwenecki 104, 105Belting Hans (1935–), niemiecki historyksztuki 77, 218, 222Benjamin Walter (1892–1940), niemieckiteoretyk kultury i krytyk literacki 36,219Berckheyde Gerrit (1638–1698), malarzholenderski 106Bernini Giovanni Lorenzo (1598–1680),rzeźbiarz włoski 70, 74Bertolucci Bernardo (1940–), włoski reżyserfilmowy 193, 199Bilac Olavo (1865–1918), publicysta brazylijski164Bingham George Caleb (1811–1879), artystaamerykański 125, 126, 138Boas Franz (1858–1942), antropolog niemiecko-amerykański180, 181Bonawentura (1217–1274), święty, mnichfranciszkański 72Bosch Hieronim (ok. 1450–1516), malarzniderlandzki 74Bosse Abraham (1602–1676), rytownikfrancuski 138–140Botticelli Sandro (1445–1510), malarzflorencki 51, 56, 59Bourke-White Margaret (1904–1971),artystka fotografka amerykańska 41,145Brady Mathew (1823–1896), artysta fotografamerykański 173Brahe Tycho (1456–1601), astronom duński102Braudel Fernand (1902–1985), francuskihistoryk 101, 224Brazylia 30, 80, 149, 150, 160, 215Brownlow Kevin (1938–), angielski reżyserfilmowy 188Brueghel Pieter, Starszy (ok. 1520–1569),malarz niderlandzki 138, 161, 199245

NaocznośćBruno Giordano (1548–1600), heretykwłoski 99buddyzm 56, 67, 188Buñuel Luis (1900–1983), hiszpański reżyserfilmowy 197Burckhardt Jacob (1818–1897), szwajcarskihistoryk kultury 29, 51, 212, 213,219Burke Edmund (1729–1797), irlandzkimyśliciel polityczny 64California State Emergency Relief Administration40Callot Jacques (ok. 1592–1635), artystaz Lotaryngii 70, 174Camille Michael (1958–2002), amerykańskihistoryk sztuki 132, 219, 225–227Canal Giovanni Antonio („Canaletto”,1697–1768), malarz wenecki 104, 106Capa Robert (1913–1954), artysta fotografwęgiersko-amerykański 42, 175Carpaccio Vittore (ok. 1465–1525), malarzwenecki 32, 104, 105, 113, 114,118Carr Edward H. (1892–1982), historykbrytyjski 186, 219Cassirer Ernst (1874–1975), filozof niemiecki55Cavell Edith (1865–1915), pielęgniarkaangielska 97Ceauşescu Nicolae (1918–1989), dyktatorrumuński 22, 93, 96Cederström Gustaf (1845–1933), malarzszwedzki 184Cerquozzi Michelangelo (1602–1660), włoskimalarz 166Certeau Michel de (1925–1986), filozofi historyk francuski 204Charity Organisation Society 40Chéret Jules (1836–1932), plakacista francuski116Chiny 22, 35, 84, 99, 102, 114, 130, 131,134, 147chłopstwo 141, 143, 145, 161, 162Constable John (1776–1837), malarz angielski64Cranach Lucas, Starszy (1472–1553), artystaniemiecki 75, 76, 176, 199Crane Stephen (1871–1900), pisarz amerykański174, 228Crivelli Carlo (ok. 1430–1495), malarzwenecki 110czytanie obrazów 53, 54, 167, 203Daguerre Louis (1787–1851), francuskiwynalazca dagerotypu 41Dali Salvador (1904–1989), malarz hiszpański61Dardel Fritz Ludvig von (1817–1901),szwedzki wojskowy i artysta 118, 119,145Daumier Honoré (1808–1879), artystafrancuski 100, 207David Jacques-Louis (1748–1825), malarzfrancuski 90, 91, 93, 96, 164,186, 208Davis Natalie Z. (1929–), historyk amerykańska190, 229, 230Debret Jean-Baptiste (1768–1848), artystafrancuski 102Degas Edgar (1834–1917), artysta francuski160Delacroix Eugène (1798–1863), malarzfrancuski 33, 34, 82, 83, 140, 152–155, 207Delaroche Paul (1797–1856), malarz francuski184, 186, 189Delumeau Jean (1923–), historyk francuski74, 222Deneuve Catherine (1943–), aktorka francuska116Depardieu Gérard (1948–), aktor francuski190Derrida Jacques (1930–2004), filozof francuski203Desjardins Martin (1637–1694), rzeźbiarzflamandzko-francuski 89Desmoulins Camille (1760–1794), publicystai polityk francuski 100Douglas David C. (1898–1982), historykbrytyjski 28, 219Doyle Arthur Conan, sir (1859–1930), pisarzbrytyjski 51, 101Drebbel Cornelis (ok. 1572–1633), wynalazcaholenderski 105druk 35246

IndeksDryden John (1631–1700), poeta angielski149Duplessis Joseph-Siffréde (1725–1802),malarz francuski 47Dürer Albrecht (1471–1528), artysta niemiecki19, 20, 114dzieci 40, 75, 92, 108, 126–130, 160,175, 214Eco Umberto (1932–), włoski semiotyki powieściopisarz 51, 116, 200, 202,224, 230„efekt realności” 40, 108, 154, 194Eisenstein Siergiej (1898–1948), rosyjskireżyser filmowy 188, 206Elżbieta I (panowanie 1558–1601), królowaAnglii 79Erlanger Philippe (1903–1987), historykfrancuski 189, 190Eugeniusz (1865–1947), szwedzki książęi artysta 63Eyck Jan van (ok. 1389–1441), malarzflamandzki 29, 32, 54Falconet Etienne-Maurice (1716–1791),rzeźbiarz francuski 88Félibien André (1619–1695), francuskikrytyk sztuki 142Fellini Federico (1920–1993), włoski reżyserfilmowy 187Fenton Roger (1819–1869), artysta fotografangielski 173formuła 117, 168, 169, 171, 172, 179, 201fotografia lotnicza 43fotografia społeczna 40Foucault Michel (1926–1984), filozof francuski53, 200, 201, 230Fox Charles James (1749–1806), politykangielski 97, 98Fox Talbot William Henry (1800–1877),artysta fotograf angielski 126, 225Fragonard Jean-Honoré (1732–1806), artystafrancuski 137Franciszek Ksawery (1506–1552), świętyhiszpański 147Freedberg David (1948–), brytyjski historyksztuki 77, 205, 206, 222, 231Freud Zygmunt (1856–1939), psychoanalitykaustriacki 51, 195–197Freyre Gilberto (1900–1987), socjologi historyk brazylijski 30Fried Michael (1939–), amerykański historyksztuki 205, 231Friel Brian (1929–), dramatopisarz północnoirlandzki194Fryderyk Wilhelm zw. Wielkim Elektorem(panowanie 1640–1688), elektorbrandenburski i książę pruski 87, 184Gainsborough Thomas (1727–1788), malarzangielski 44Gama Vasco da (ok. 1469–1525), podróżnikportugalski 146, 207Gardner Robert (1925–), amerykański reżyserfilmowy 181Geertz Clifford (1926–2006), antropologamerykański 201, 202, 230Gérard François (1770–1837), malarz francuski91, 93Géricault Théodore (1791–1824), francuskimalarz 152, 153Gérôme Jean-Léon (1824–1904), malarzfrancuski 152, 153Gerz, Jochen i Esther, rzeźbiarze niemieccy99Gierasimow Aleksander (1881–1963), malarzrosyjski 96Gierasimow Siergiej W. (1885–1964), malarzrosyjski 143Gillray James (1756–1815), artysta angielski18, 100Gilman Sander L. (1944–), amerykańskihistoryk sztuki 163, 227Gilpin William (1724–1804), pisarz angielski64Ginzburg Carlo (1939–), historyk włoski51, 196, 220, 230Giorgione (ok. 1478–1510), malarz wenecki63Goethe Johann Wolfgang von (1749–1832), pisarz niemiecki 122, 123Goffman Erving (1922–1982), socjologamerykański 220, 224Gombrich Ernst H. (1909–2001), austriacko-brytyjskihistoryk sztuki 32, 50,56, 61, 219–221, 223Goubert Pierre (1915–2012), historykfrancuski 141, 226247

NaocznośćGoya Francisco de (1746–1828), malarzhiszpański 44, 164Graham-Brown Sarah, historyk fotografii41, 220, 225, 227Grégoire Henri (1750–1831), francuskiduchowny, pisarz, publicysta, działaczpolityczny 98Grenville John (1928–2011), historyk brytyjski186, 229Grien Hans Baldung (ok. 1476–1545), artystaniemiecki 76, 160Griffith D.W. (1875–1948), amerykańskireżyser filmowy 183, 185, 186, 207Gros Antoine-Jean (1771–1835), malarzfrancuski 172Grosz Georg (1893–1959), artysta niemiecki159, 160Grzegorz I Wielki (ok. 540–604), papież54, 66, 68, 75Guanyin, buddyjska bogini miłosierdzia60, 147Guicciardini Francesco (1483–1540), historykwłoski 172Guys Constantin (1802–1892), artystafrancuski 34, 154, 173Hale John R. (1923–2000), historyk angielski171, 228Haskell Francis (1928–2000), brytyjskihistoryk sztuki 29, 31, 184, 205, 219,229, 231Hauser Arnold (1892–1978), węgierskihistoryk sztuki 50, 61, 204, 220, 228Hellqvist Carl (1851–1890), malarzszwedzki 184Herodot (ok. 484–ok. 420 BC), historykgrecki 147Hersent Louis (1777–1860), malarz francuski47, 208Hill Christopher (1912–2003), historykbrytyjski 188hinduizm 56, 67Hine Lewis (1874–1940), artysta fotografamerykański 39, 40Hitler Adolf (1889–1945), dyktator niemiecki22, 29, 48, 54, 92, 93, 96, 164,182, 193Hogarth William (1697–1764), artysta angielski126–128, 130, 131, 138, 140,156, 168, 176, 199, 209Holmes Sherlock, powieściowy detektyw50, 51, 101Hooch Pieter de (1629–1684), malarz holenderski54, 108, 109Huizinga Johan (1879–1945), holenderskihistoryk kultury 29, 61, 180, 219Hunt William Holman (1827–1910), malarzangielski 184idealizacja 96, 117, 140, 141, 178ikona, ikonostas 34, 70, 72, 74, 89, 96ikonografia 52–55, 57, 62, 67, 68, 81, 84,86, 93, 194, 195, 201, 202, 212ikonoklazm 75, 77, 98, 99, 208ikonologia 53, 54, 56, 60–62, 195, 202„ikonoteksty” 59, 85, 168, 185, 203, 209Ingres Jean-Auguste-Dominique (1780–1867), malarz francuski 49, 93, 152,153intertekstualność 21, 118Ivins William H., junior (1881–1961),amerykański kurator grafiki 35, 219Izquierdo Sebastian (1601–1681), jezuitahiszpański 73Jancsó Miklós (1921–), węgierski reżyserfilmowy 191, 192Japonia 115, 130, 131, 188Jaucourt Louis de (1704–1779), literatfrancuski 79, 80Joanna d’Arc (ok. 1412–1431), francuskabohaterka narodowa, święta Kościołakatolickiego 73Johnson Eastman D.H. (1824–1906), malarzamerykański 33, 155, 229Jongh Eddy de (1931–), holenderski historyksztuki 56, 110, 129, 196, 197,221, 224, 230kanibale 149–151, 160, 196Karol V (panowanie 1516–1555), cesarzŚwiętego Cesarstwa Rzymskiego NaroduNiemieckiego 24, 38, 44, 81, 89,165, 169, 173, 177, 178karykatura 100, 145, 158, 159, 206, 207Klee Paul (1879–1940), artysta szwajcarski66Kleiner Salomon (1703–1761), artysta niemiecki131248

Redaktor inicjującyRedaktorKorektaSkład i łamanieOlaf PietekJadwiga MakowiecDagmara MałyszaHanna WiecheckaNakład 1000 egz., ark. wyd. 17<strong>Wydawnictwo</strong> <strong>Uniwersytetu</strong> JagiellońskiegoRedakcja: ul. Michałowskiego 9/2, 31-126 Krakówtel. 12-631-18-81, 12-631-18-82, fax 12-631-18-83