land use and land tenure change in the - El Colegio de Chihuahua

land use and land tenure change in the - El Colegio de Chihuahua

land use and land tenure change in the - El Colegio de Chihuahua

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

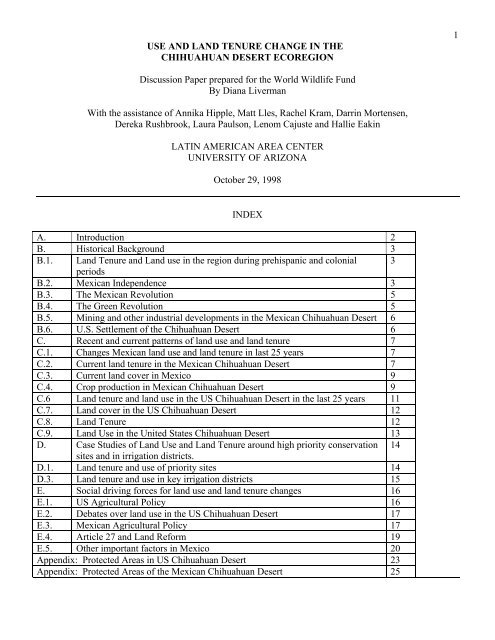

USE AND LAND TENURE CHANGE IN THECHIHUAHUAN DESERT ECOREGION1Discussion Paper prepared for <strong>the</strong> World Wildlife FundBy Diana LivermanWith <strong>the</strong> assistance of Annika Hipple, Matt Lles, Rachel Kram, Darr<strong>in</strong> Mortensen,Dereka Rushbrook, Laura Paulson, Lenom Cajuste <strong>and</strong> Hallie Eak<strong>in</strong>LATIN AMERICAN AREA CENTERUNIVERSITY OF ARIZONAOctober 29, 1998INDEXA. Introduction 2B. Historical Background 3B.1. L<strong>and</strong> Tenure <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region dur<strong>in</strong>g prehispanic <strong>and</strong> colonial 3periodsB.2. Mexican In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce 3B.3. The Mexican Revolution 5B.4. The Green Revolution 5B.5. M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>de</strong>velopments <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 6B.6. U.S. Settlement of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 6C. Recent <strong>and</strong> current patterns of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> 7C.1. Changes Mexican <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> last 25 years 7C.2. Current <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 7C.3. Current <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> cover <strong>in</strong> Mexico 9C.4. Crop production <strong>in</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 9C.6 L<strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last 25 years 11C.7. L<strong>and</strong> cover <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 12C.8. L<strong>and</strong> Tenure 12C.9. L<strong>and</strong> Use <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 13D. Case Studies of L<strong>and</strong> Use <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong> Tenure around high priority conservation 14sites <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> irrigation districts.D.1. L<strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> of priority sites 14D.3. L<strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> key irrigation districts 15E. Social driv<strong>in</strong>g forces for <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>change</strong>s 16E.1. US Agricultural Policy 16E.2. Debates over <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 17E.3. Mexican Agricultural Policy 17E.4. Article 27 <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong> Reform 19E.5. O<strong>the</strong>r important factors <strong>in</strong> Mexico 20Appendix: Protected Areas <strong>in</strong> US <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 23Appendix: Protected Areas of <strong>the</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert 25

A. Introduction2L<strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> are important <strong>in</strong>fluences on biological diversity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desertecoregion. The conversion of forests <strong>and</strong> natural grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s to graz<strong>in</strong>g or crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> alters <strong>the</strong> habitats ofmany species. Irrigation of dry<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s or dra<strong>in</strong>age of wet<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s also transforms <strong>the</strong> ecosystem <strong>in</strong> ways thataffect biodiversity. The <strong>in</strong>tensification of agriculture through <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>use</strong> of agricultural chemicals posespollution risks. Industrial <strong>de</strong>velopments such as m<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> smelters can result <strong>in</strong> vegetation loss <strong>and</strong>pollution. Urban <strong>de</strong>velopment encroaches on natural <strong>and</strong> agricultural ecosystems. Changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong>management are be<strong>in</strong>g driven by a range of social factors <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>de</strong>mographic, political, technologica<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> economic conditions, especially <strong>change</strong>s <strong>in</strong> agricultural policy.The goal of this background document is to <strong>de</strong>scribe <strong>the</strong> present state of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert region as <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> WWF biology workshop <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> major socioeconomicforces that are driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>change</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region. Major <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> over types (forest, pasture, irrigated <strong>and</strong> ra<strong>in</strong> fedcrop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>) <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong>s (crop, types, forest product <strong>use</strong>) are <strong>de</strong>scribed as well as patterns of public <strong>and</strong>private <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong>s <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g fe<strong>de</strong>ral state <strong>and</strong> local government, ejidos, <strong>and</strong> private sector. The <strong>use</strong> ofresources on public <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s (graz<strong>in</strong>g, timber, traditional resource <strong>use</strong>, <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g) will be <strong>de</strong>scribed. Thepaper reviews important historical processes such as Mexican <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> reform, US public <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> policies, <strong>and</strong>chang<strong>in</strong>g agricultural policy <strong>and</strong> markets. One important objective of this paper is to geographicallydisaggregate <strong>the</strong> patterns <strong>and</strong> processes of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> so as to <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> range <strong>and</strong> variety ofsocioeconomic pressures on <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert biodiversity. The goal is to provi<strong>de</strong> a variety of i<strong>de</strong>as tostimulate discussion at <strong>the</strong> fall workshop.For <strong>the</strong> purposes of this paper we <strong>use</strong>d <strong>the</strong> geographical <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert from<strong>the</strong> Monterrey WWF workshop. We superimposed <strong>the</strong> GIS layers which provi<strong>de</strong>d <strong>the</strong> ecological boundaryof <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert on political maps of he region <strong>in</strong> or<strong>de</strong>r to i<strong>de</strong>ntify those municipios <strong>and</strong> counties that are, for<strong>the</strong> most part <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert region. We were <strong>the</strong>n able to <strong>use</strong> recent census data tocharacterize <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. We wanted to <strong>use</strong> such local level data ra<strong>the</strong>rthan state summaries beca<strong>use</strong> large parts of <strong>the</strong> states (such as Texas <strong>and</strong> Sonora) are not <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert <strong>and</strong> beca<strong>use</strong> state level summaries hid tremendous geographical <strong>and</strong> social variations as more locallevels. The counties <strong>and</strong> municipios <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> study are shown <strong>in</strong> Figures 1 <strong>and</strong> 2. The <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert extends <strong>in</strong>to all or part of three counties of sou<strong>the</strong>astern Arizona, eight sou<strong>the</strong>rn counties of NewMexico <strong>and</strong> 11 of <strong>the</strong> westernmost counties of <strong>the</strong> Trans Pecos Texas. In Texas, <strong>the</strong>se counties are <strong>El</strong> Paso,Hudspeth, Brewster, Ward, Presidio, Terrell, Pecos, Reeves, Culberson, Jeff Davis, <strong>and</strong> Lov<strong>in</strong>g. In NewMexico, <strong>the</strong> counties are Hidalgo, Grant, Sierra, Luna, Eddy, Otero, Dona Ana, <strong>and</strong> part of Chavez. And <strong>in</strong>Arizona, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert covers all of Cochise County, <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn part of Safford, <strong>and</strong> extends <strong>in</strong>toSanta Cruz. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> WWF map, it extends <strong>in</strong>to Pima but where it does, <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is wil<strong>de</strong>rness <strong>and</strong>range, <strong>and</strong> is consi<strong>de</strong>red by most to be part of <strong>the</strong> Sonoran/<strong>Chihuahua</strong>n transition zone. We have not, at thispo<strong>in</strong>t, been able to l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> GIS for US <strong>and</strong> Mexican portions of <strong>the</strong> Desert.We selected several of <strong>the</strong> high priority terrestrial sites i<strong>de</strong>ntified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Monterrey workshop formore <strong>in</strong>tensive analysis of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> as reported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990 Mexican Agricultural Census. These<strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d <strong>the</strong> Chiricahua/San Pedro area, <strong>the</strong> Mapimi, <strong>and</strong> Cuatro Cienegas regions. We also ga<strong>in</strong>ed fur<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> major irrigation districts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert from a 1990 report of <strong>the</strong>Mexican irrigation districts.The first section provi<strong>de</strong>s a brief history of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> factors that have driven<strong>the</strong>ir transformation. The second section discusses <strong>the</strong> current patterns of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> for <strong>the</strong>US <strong>and</strong> Mexican counties of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert <strong>and</strong> for high priority conservation sites. The thirdsection discusses <strong>the</strong> current legal economic. And political context for <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>region, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> paper conclu<strong>de</strong>s with a discussion of trends <strong>and</strong> projections to <strong>the</strong> future <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, forexample, <strong>the</strong> impacts of NAFTA, Mexico’s agrarian reforms, <strong>and</strong> new <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> policies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States.

B. Historical Background3B.1.L<strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region dur<strong>in</strong>g prehispanic <strong>and</strong> colonial periodsUntil <strong>the</strong> Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, for which 1998 makes <strong>the</strong> 150 th anniversary, most of <strong>the</strong><strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert shared a common history of Indian <strong>and</strong> colonial Spanish settlement. The physicalgeography of <strong>the</strong> region, especially <strong>the</strong> availability of water, has <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues to <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>e settlement <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><strong>use</strong> patterns, Prior to <strong>the</strong> arrival of Europeans <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Americas, <strong>the</strong> peoples <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert region consisted primarily of small b<strong>and</strong>s of hunters <strong>and</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>rers engaged <strong>in</strong> seasonal rounds,although some groups established permanent settlements where resources permitted. The collective termfor <strong>the</strong>se groups was “Chichimec”, although <strong>the</strong>y spoke many different languages. The mesquite bush wasan important basic food source. The <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples of <strong>the</strong> region established settlements along <strong>the</strong> RioGr<strong>and</strong>e <strong>and</strong> Pecos River Valleys <strong>in</strong> New Mexico <strong>and</strong> West Texas, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> San Pedro River valley <strong>in</strong>Arizona, where water was plentiful <strong>and</strong> agriculture could be supported. In Mexico, importantarchaeological sites such as Casas Gr<strong>and</strong>es <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> legacies of early occupancy of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert. The San Pedro valley conta<strong>in</strong>s one of <strong>the</strong> most important archaeological sites where <strong>the</strong>re isevi<strong>de</strong>nce of <strong>the</strong> so-called “Pleistocene overkill”- <strong>the</strong> hunt<strong>in</strong>g of megafauna by early peoples, perhaps to <strong>the</strong>level of ext<strong>in</strong>ction.The Spanish were <strong>in</strong>itially <strong>in</strong>timidated by <strong>the</strong> harsh environment <strong>and</strong> peoples of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert, but <strong>the</strong> discovery of silver <strong>in</strong> Zacatecas <strong>in</strong> 1546 <strong>in</strong>itiated a northward movement of Spanish settlersfollow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> silver ores of <strong>the</strong> sierra Madre Occi<strong>de</strong>ntal culm<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> famous m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g settlement ofParral established <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1631 (Figure 3). Ano<strong>the</strong>r route of Spanish conquest followed <strong>the</strong> routeof Coronado along <strong>the</strong> San Pedro River, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> establishment of missions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rio Sonora valley. Them<strong>in</strong>es became <strong>the</strong> markets for a livestock <strong>in</strong>dustry that was established on <strong>the</strong> high grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s of <strong>the</strong><strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. By <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> 18 th century ranchers <strong>and</strong> missionaries, supported militarily byPresidios, had crossed <strong>the</strong> Rio Gr<strong>and</strong>e <strong>in</strong>to Texas, <strong>and</strong> stock rais<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g had become <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><strong>use</strong>s of nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico (West <strong>and</strong> Augelli, 1989).The area cont<strong>in</strong>ued to be sparsely <strong>in</strong>habited <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early colonial period, nom<strong>in</strong>ally un<strong>de</strong>r <strong>the</strong> controlof <strong>the</strong> Spanish crown. The dom<strong>in</strong>ant economic activity was m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, which generated a <strong>de</strong>m<strong>and</strong> for food,tallow, hi<strong>de</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r products produced with Indian labor on large estates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region. The crown ma<strong>de</strong>some enormous <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> grants <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico. For example <strong>the</strong> marquis <strong>de</strong> Aguayo received an estate half<strong>the</strong> size of present day Coahuila. These estates were ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>use</strong>d for rais<strong>in</strong>g cattle, but several alsoproduced wheat <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r crops for <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r settlements (figure 4). The Apache were one ofseveral Indian groups who resisted Spanish dom<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> attacked settlements to obta<strong>in</strong> cattle <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rresources.By <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> colonial period human activity had already altered <strong>the</strong> biodiversity of <strong>the</strong><strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. Impacts <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d possible over hunt<strong>in</strong>g of large mammals at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> ice age, <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>tentional <strong>and</strong> acci<strong>de</strong>ntal <strong>use</strong> of fire <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s, <strong>the</strong> domestication of maize <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r crops, earlyirrigation systems, <strong>in</strong>troduction of cattle <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r exotics by <strong>the</strong> Spanish, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>struction of forests form<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. European dom<strong>in</strong>ance also shifted attitu<strong>de</strong>s to nature from a relationship based on <strong>use</strong> values <strong>and</strong>flexible or communal <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itions of property to <strong>the</strong> view of resources as commodities to be bought <strong>and</strong> sold,<strong>and</strong> to private, often enclosed, property. The Catholic religion also rejected <strong>the</strong> animistic <strong>and</strong> pan<strong>the</strong>istictraditional beliefs of <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples that often resulted <strong>in</strong> a respectful ra<strong>the</strong>r than exploitative relation tonature.B.2.Mexican In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nceWhen Mexico ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce from Spa<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Mexican government cont<strong>in</strong>ued to offergenerous <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> grants to those will<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>de</strong>fend <strong>the</strong> area aga<strong>in</strong>st Apache attacks. This created an alliancebetween peasants <strong>and</strong> hacendados (large <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hol<strong>de</strong>rs) at <strong>the</strong> same time that <strong>the</strong> peasantry was los<strong>in</strong>g ground

4<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> country (Katz 14). Dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, Mexican regions reta<strong>in</strong>ed significant <strong>de</strong>grees ofautonomy <strong>and</strong> policies o<strong>the</strong>r started at <strong>the</strong> state level. One such state program was <strong>the</strong> abolition ofcommunal <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> ownership that transformed many Indian hold<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>to private property (<strong>Chihuahua</strong> 1825;Zacatecas 1825; S<strong>in</strong>aloa <strong>and</strong> Sonora 1828). The national-level Ley Lerdo (1856) cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>the</strong>se policies,provid<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> breakup of communal <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> hold<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> expropriated <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> hold<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong> Church,although some regions provi<strong>de</strong>d for communal hold<strong>in</strong>gs to avoid <strong>the</strong> dangers of social <strong>in</strong>stability that mightarise from large numbers of <strong>in</strong>digenous <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>less. Although <strong>the</strong> stated <strong>in</strong>tent beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>se reforms was <strong>the</strong>creation of Jeffersonian yeoman farmers, <strong>the</strong> expropriated <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> was auctioned to <strong>the</strong> highest bid<strong>de</strong>r <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>most frequent result was extensive private estates, which contributed to <strong>the</strong> concentration of regionaleconomic power <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s of a few families. The <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> laws of 1875<strong>and</strong> 1883 that permitted <strong>in</strong>dividualsto acquire vacant or untitled <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s also re<strong>in</strong>forced <strong>the</strong> concentration of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> hold<strong>in</strong>gs. Indigenous groupswere often forced onto more marg<strong>in</strong>al <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s, <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> Sierra, or became peon laborers on <strong>the</strong> large haciendasbeca<strong>use</strong> <strong>the</strong>y could not prove legal title.The n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century also saw massive <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> transfers from Mexico to <strong>the</strong> United States through aseries of wars <strong>and</strong> treaties. When Texas won <strong>in</strong><strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce from Mexico <strong>in</strong> 1836 its territory <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d someof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. Most of New Mexico <strong>and</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Arizona was acquired from Mexico after <strong>the</strong>U.S. – Mexican War (1846-48) through <strong>the</strong> Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. More territory, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gSou<strong>the</strong>rn Arizona <strong>and</strong> Mesilla, was acquired <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1953 Gads<strong>de</strong>n Purchase, <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> L<strong>and</strong> Grantsestablished by Spanish <strong>and</strong> Mexican governments were to be respected.The autonomy of <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn states of Mexico was reduced with <strong>the</strong> construction of railroads <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>late 1800’s, although local politicians <strong>and</strong> families dom<strong>in</strong>ated at <strong>the</strong> state <strong>and</strong> regional levels. Mexican ores,often exploited with American capital, were shipped to <strong>the</strong> U.S. for smelt<strong>in</strong>g. In <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, <strong>the</strong> cattle<strong>in</strong>dustry boomed <strong>and</strong> at <strong>the</strong> national level commercial production for export replaced subsistence agriculture<strong>and</strong> small-scale farm<strong>in</strong>g. The <strong>in</strong>troduction of irrigation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Laguna region of Coahuila <strong>and</strong> Durangocreated a boom<strong>in</strong>g cotton <strong>in</strong>dustry; from 1880 to 1890 production qu<strong>in</strong>tupled, <strong>and</strong> it doubled <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> (MacLachian <strong>and</strong> Beezley 113).Regional <strong>in</strong>dustries <strong>de</strong>veloped <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> area became one of <strong>the</strong> country’s most important <strong>in</strong>dustrialzones, with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g urbanization <strong>and</strong> a large number of immigrants from <strong>the</strong> U.S. as well as o<strong>the</strong>r regionsof Mexico, attracted by <strong>the</strong> highest agricultural wages <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country (Katz 44). The rapid expansion ofproduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north contributed to rapid rates of <strong>in</strong>-migration; by non-natives (MacLachlan <strong>and</strong> Beezley1999:125). The region’s economy was relatively diversified, produc<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>erals <strong>and</strong> agricultural <strong>and</strong>timber products for exports, as well as goods for <strong>the</strong> local market (Katz 34). Economic <strong>and</strong> political powergenerally rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s of families who dom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong>ir states: <strong>the</strong> Terrazas-Creel <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>,<strong>the</strong> Ma<strong>de</strong>ros <strong>in</strong> Coahuila, <strong>and</strong> a h<strong>and</strong>ful of <strong>in</strong>dustrialists <strong>in</strong> Monterrey (Katz 43). By <strong>the</strong> turn of <strong>the</strong> century,<strong>the</strong> north could be consi<strong>de</strong>red <strong>the</strong> most mo<strong>de</strong>rn region of <strong>the</strong> country, with a relatively urban population,diversified economy, <strong>and</strong> high literacy rate.The shift to commercial export agriculture put pressure on domestic food supplies; by <strong>the</strong> 1870sprotests, such as food riot <strong>in</strong> Durango <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g 4000 people (Maclachlan <strong>and</strong> Beezley 189), started to breakout. From <strong>the</strong> 1890s onwards. Mexico cont<strong>in</strong>ually imported staple foodstuffs <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> concentration of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>elim<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong> possibility of subsistence agriculture provid<strong>in</strong>g any sort of safety net. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>privatization of municipal <strong>and</strong> communal <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s cont<strong>in</strong>ued, allow<strong>in</strong>g both foreigners <strong>and</strong> Mexicans toacquire <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> large <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>gs. In 1907, a recession <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S. dragged <strong>the</strong> Mexican economy <strong>in</strong>toa downturn with fall<strong>in</strong>g wages <strong>and</strong> mass layoffs, exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> return of migrant workers fro <strong>the</strong> U.S.<strong>and</strong> a co<strong>in</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>nt agricultural crisis precipitated by floods <strong>and</strong> droughts (Katz 64). This crisis hit particularlyhard <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north, contribut<strong>in</strong>g to a united opposition to <strong>the</strong> national government. The hacendados of <strong>the</strong>region did not have a dispossessed peasant class to fear, <strong>the</strong>y had claimed un<strong>in</strong>habited <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s <strong>and</strong> many<strong>de</strong>veloped a paternalistic relationship with <strong>the</strong>ir peons who received relatively high wages <strong>and</strong> <strong>de</strong>grees offreedom (72).Porfirio Diaz was presi<strong>de</strong>nt of Mexico from 1877 to 1911, <strong>and</strong> un<strong>de</strong>r his dictatorship <strong>and</strong>encouragement of foreign <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>the</strong> economy grew rapidly.

Wi<strong>de</strong>spread discontent with foreign control, <strong>the</strong> concentration of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong>to large private properties,<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> impoverishment of <strong>the</strong> masses led to unrest, support for opposition lea<strong>de</strong>r Francisco Ma<strong>de</strong>ro, <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> Mexican Revolution.5B.3.The Mexican RevolutionFrom 1910 to 1917 <strong>the</strong> Mexican Revolution raged across nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico, with lea<strong>de</strong>rs such asZapata, Villa, Carranza <strong>and</strong> Ma<strong>de</strong>ro compet<strong>in</strong>g for power. The Revolution <strong>de</strong>vastated <strong>the</strong> countrysi<strong>de</strong> asrural people ab<strong>and</strong>oned <strong>the</strong>ir crops, government support disappeared, <strong>and</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>stability <strong>in</strong>creased.Despite <strong>the</strong> election of Carranza as presi<strong>de</strong>nt as Presi<strong>de</strong>nt <strong>in</strong> 1917, <strong>and</strong> establishment of a new constitution,it was not until <strong>the</strong> mid-1920s that partial stability returned to Mexico <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> new constitution was fullyimplemented.The Revolutionary constitution had great significance for <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnMexico. It <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d <strong>the</strong> rejection of foreign ownership of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> resources such as copper <strong>and</strong> oil, <strong>the</strong>restitution of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> to <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples, <strong>the</strong> redistribution of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of communal ejidos, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>expropriation of church property. The breakup of <strong>the</strong> large haciendas had no s<strong>in</strong>gle result for ecosystems.In some cases, <strong>the</strong> ejidos chose to place more cattle or to convert grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> to crops, <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong><strong>in</strong>tensity <strong>de</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ed beca<strong>use</strong> of lack of technical expertise or credit.The full implementation of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> reform began with <strong>the</strong> presi<strong>de</strong>ncy of Lazaro Car<strong>de</strong>nas <strong>in</strong> 1934(figure 5) who also nationalized <strong>the</strong> railroads <strong>and</strong> oil. Dur<strong>in</strong>g his presi<strong>de</strong>ncy vast areas of productivity ofstate owned <strong>in</strong>dustry resulted <strong>in</strong> some expansion of resource extraction.B.4.The Green RevolutionThe 1950s brought several important <strong>change</strong>s of relevance to <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Chihuahua</strong>n <strong>de</strong>sert. In 1952, labor migration from Mexico to <strong>the</strong> United States was formalized through <strong>the</strong>Bracero guest farm worker program, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> millions of Mexicans travel<strong>in</strong>g to work on US farms over<strong>the</strong> next two <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s. This alternative employment opportunity resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ab<strong>and</strong>onment of some of <strong>the</strong>more marg<strong>in</strong>al <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s. This trend was exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> onset of <strong>the</strong> 1950s drought. This drought, <strong>the</strong> mostsevere on record <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, resulted <strong>in</strong> wi<strong>de</strong>spread losses of crops <strong>and</strong> livestock as well as long temdamage to natural ecosystems. The Palmer Drought Severity In<strong>de</strong>x show values below –2 for this period<strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g extreme drought conditions (figure 6).However, <strong>the</strong> Bracero program resulted <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> agriculture <strong>in</strong> Mexico as workerssent remittances back to <strong>the</strong>ir families. It has been estimated that <strong>the</strong>se remittances now provi<strong>de</strong> more than50% of local <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> many rural communities.At <strong>the</strong> same time, however, <strong>the</strong> Mexican government, with <strong>in</strong>ternational assistance from <strong>the</strong>Rockefeller Foundation, <strong>in</strong>itiated a new agricultural <strong>de</strong>velopment program to <strong>in</strong>crease yields of wheat <strong>and</strong>maize through <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> of improved seeds, irrigation districts of nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico, where governmentprograms distributed improved wheat varieties <strong>and</strong> fertilizer. In many cases, yields <strong>in</strong>creased dramatically,<strong>and</strong> Mexican wheat production soared (Figure 7).Some see <strong>the</strong> Green Revolution as a great success (Welha<strong>use</strong>n, 1976; Yates, 1981) po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g tobenefits <strong>in</strong> improved nutrition, farm <strong>in</strong>comes, exports, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensification of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> (ra<strong>the</strong>r thanconversion of un<strong>de</strong>veloped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>).O<strong>the</strong>rs are far more critical, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that unequal access to irrigated <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, credit <strong>and</strong> technologyresulted <strong>in</strong> only a few regions <strong>and</strong> people reap<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> benefits, <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong> new <strong>in</strong>puts of seeds, water, <strong>and</strong>chemicals damaged ecosystems through loss of diversity, sal<strong>in</strong>ization, <strong>and</strong> pollution (Wright, 1991).S<strong>in</strong>ce 1960 yields of basic crops have <strong>in</strong>creased significantly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> states of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert.Wheat acreage <strong>in</strong>creased as a result of <strong>the</strong> Green Revolution, but was followed by a shift from basic gra<strong>in</strong>sto forage <strong>and</strong> vegetable production. Sorghum <strong>and</strong> alfalfa production has been <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1960s

toge<strong>the</strong>r with an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> oilseeds <strong>in</strong> some irrigation districts. Overall crop acreage <strong>in</strong>creased with <strong>the</strong><strong>de</strong>velopment of major irrigation districts.The agricultural <strong>in</strong>tensification of parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert has affected several importantecosystems. For example, <strong>the</strong> expansion of irrigation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> La Laguna area, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> of agriculturalchemicals has reduced <strong>and</strong> put at risk areas of importance to migratory birds <strong>and</strong> amphibians.6B.5.M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>de</strong>velopments <strong>in</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n DesertMetal production <strong>in</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico grew consi<strong>de</strong>rably from 1920 to 1940, especially <strong>in</strong> Sonora<strong>and</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> where gold production reached almost 10,000 kg by 1940, 350,000 kg of silver, 9,500 tonsof copper, <strong>and</strong> 1.2 million tons of iron.Sonora produced 100 kg of gold, 236.00 kg of silver, <strong>and</strong> 153,000 tons of copper by 1980, <strong>and</strong>Coahuilan silver production had grown to almost 60,000 kg. With iron production of 250,000 tons (lorey,1990) (Figure 8).B.6.U.S. Settlement of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n DesertSimilar patterns of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> based on m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> cattle are found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US portion of <strong>the</strong><strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. Anglo settlement of <strong>the</strong> U.S. portion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert occurred ma<strong>in</strong>ly after<strong>the</strong> U.S. Civil War. The war brought many Anglo soldiers to <strong>the</strong> southwest U.S. for <strong>the</strong> first time, <strong>and</strong> manyreturned with <strong>the</strong>ir families to homestead <strong>the</strong> rich river valleys <strong>and</strong> graze livestock on <strong>the</strong> extensivegrass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s after <strong>the</strong> war. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave settlers160 acres, but allotments were laterexp<strong>and</strong>ed to 640 acres by <strong>the</strong> Desert L<strong>and</strong> Act of 1875 (later reduced aga<strong>in</strong> to 320 acres) to allow forlivestock graz<strong>in</strong>g, which at <strong>the</strong> time was necessary for survival. Ineffective regulation of graz<strong>in</strong>g let to <strong>and</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ues to <strong>de</strong>gra<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong> ranges <strong>in</strong> all states.After <strong>the</strong> Civil War cotton emerged as <strong>the</strong> major crop <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region. It was found to be resistant toharsh conditions, adaptable to phosphate-poor soils <strong>and</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>e water, valuable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>greconstruction economy, <strong>and</strong> less damag<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> soil. Specialized cash-crop farm<strong>in</strong>g became <strong>the</strong> norm.And many of <strong>the</strong> new homestea<strong>de</strong>rs were mid-westerners who imported <strong>the</strong>ir crops, like wheat, barley,corn, beans, <strong>and</strong> hay, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir farm<strong>in</strong>g techniques to <strong>the</strong> more <strong>de</strong>licate <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert,lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>de</strong>vastat<strong>in</strong>g effects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1930;s when <strong>in</strong>appropriate <strong>use</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> let to <strong>the</strong> Dustbowl.Cotton also allowed for growth of sp<strong>in</strong>-off <strong>in</strong>dustries as technology became available to fur<strong>the</strong>rref<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> cottonseed <strong>in</strong>to value-ad<strong>de</strong>d products like oil <strong>and</strong> textiles. Cotton also <strong>change</strong>d <strong>the</strong> labor <strong>and</strong>tenancy relations. An <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g number of sharecropp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> tenant farmers let to an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g number ofpeople whose livelihood relied on agricultural production <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert with fewer <strong>and</strong> fewerpeople own<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> means of production. As important as cotton became, <strong>the</strong> extensive <strong>use</strong> of<strong>the</strong> range for cattle graz<strong>in</strong>g characterized all parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. In 1878, barbed wire ma<strong>de</strong> itsappearance on <strong>the</strong> range, <strong>and</strong> cattle could for <strong>the</strong> first time be controlled on <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> hold<strong>in</strong>gs. Thisled to <strong>the</strong> need to legally <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>e boundaries <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Desert.The railroad (1891) spurred growth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area of not only of <strong>the</strong> urban areas of Las Cruces, <strong>El</strong> Paso,<strong>and</strong> Albuquerque, but also exp<strong>and</strong>ed commercial agricultural <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area as it allowed larger quantities ofagricultural products to reach exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g markets <strong>in</strong> all parts of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Cattle ranch<strong>in</strong>g experienced a hugeboom <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1880’s – 1890’s as did corn <strong>and</strong> cotton operations. While cattle never excee<strong>de</strong>d corn <strong>and</strong>cotton <strong>in</strong> value dur<strong>in</strong>g this time, it dom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> of <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. Agricultural expansionwas always, <strong>and</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s, limited by <strong>the</strong> availability of water.M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, ma<strong>in</strong>ly of copper, also became a predom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>use</strong> of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. Them<strong>in</strong>es ma<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir mark on <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> by <strong>the</strong> open pits (which came <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1940s), <strong>the</strong> huge tail<strong>in</strong>gs, slag <strong>and</strong>waste dumps, <strong>and</strong> especially by <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>nud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>de</strong>forestation of surround<strong>in</strong>g areas.It was <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early p art of this century that <strong>the</strong> different states took different paths to <strong>de</strong>velopment.This was largely due to technology <strong>and</strong> resources, but also culture. In 1900 homestead<strong>in</strong>g was en<strong>de</strong>d <strong>and</strong>

7Turner <strong>de</strong>clared <strong>the</strong> clos<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> American frontier. Arizona <strong>and</strong> New Mexico were still isolated frommuch of <strong>the</strong> US economy <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fe<strong>de</strong>ral government held <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. In contrast, 98% ofTexas <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> was <strong>in</strong> private h<strong>and</strong>s by 1895. Industrial <strong>de</strong>velopment <strong>in</strong> Texas was spurred by <strong>the</strong> 1901discovery of vast oil reserves at Sp<strong>in</strong>dletop.The 1902 Reclamation Act brought ushered <strong>the</strong> construction of irrigation <strong>and</strong> flood control projectsthroughout <strong>the</strong> three U.S. states that <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert, especially <strong>in</strong> New Mexico <strong>and</strong> Texas,along <strong>the</strong> Rio Gr<strong>and</strong>e <strong>and</strong> Pecos Rivers. Ground water was also tapped for <strong>the</strong> first time on an <strong>in</strong>dustrialscale by both privately fun<strong>de</strong>d <strong>and</strong> fe<strong>de</strong>ral programs.Agriculture exp<strong>and</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> contracted <strong>in</strong> boom <strong>and</strong> bust cycles <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>the</strong> discovery <strong>and</strong><strong>de</strong>pletion of new sources of water. The huge <strong>El</strong>ephant Butte Dam completed <strong>in</strong> eastern New Mexico <strong>in</strong>1915, for example, spurred agricultural <strong>and</strong> urban growth. O<strong>the</strong>r water projects such as <strong>the</strong> Avalon <strong>and</strong>McMillan dams <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roswell <strong>and</strong> Carlsbad areas of New Mexico allowed for rapid expansion ofagricultural <strong>and</strong> urban <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> those areas.The farm<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>and</strong> crops brought to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert by mid westerners, <strong>the</strong> expansionof <strong>the</strong> railroad, a plethora of new irrigation projects, <strong>and</strong> half-century of over graz<strong>in</strong>g. F<strong>in</strong>ally took its toll on<strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. A worldwi<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>pression <strong>and</strong> drought <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U. S. followed <strong>the</strong> last good farm<strong>in</strong>g season <strong>in</strong> 1929.Economic conditions both crushed <strong>de</strong>m<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> availability of credit to keep farm<strong>in</strong>g. Farmers were leftwith huge surpl<strong>use</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Dust Bowl” of <strong>the</strong> mid 1930’s stripped <strong>the</strong> fields of <strong>the</strong> topsoil.The government forced many farmers <strong>in</strong> West Texas <strong>and</strong> Eastern, New Mexico to retire <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s<strong>and</strong> sell <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> to <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> bank or BLM, or restricted <strong>the</strong>m from us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s un<strong>de</strong>r <strong>the</strong> TaylorGraz<strong>in</strong>g Act of 1934 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soil Conservation Act of 1935. Many of those families still farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Arizona <strong>and</strong> Southwestern New Mexico are <strong>the</strong> same families who moved as a result of <strong>the</strong>Dust Bowl un<strong>de</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Resettlement Adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>and</strong> Farm Security Adm<strong>in</strong>istration.Throughout <strong>the</strong> twentieth century <strong>the</strong> US fe<strong>de</strong>ral government reta<strong>in</strong>ed most of <strong>the</strong> Arizona <strong>and</strong> NewMexico portions of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> area along <strong>the</strong> Rio Gr<strong>and</strong> through Big Bend <strong>in</strong> public<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s. Beca<strong>use</strong> both <strong>the</strong> Forest Service <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> BLM foc<strong>use</strong>d on us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s forest <strong>and</strong> grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s weeheavily <strong>use</strong>d for livestock graz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> logg<strong>in</strong>g. Only <strong>the</strong> parks rema<strong>in</strong>ed relatively un<strong>use</strong>d although touristpressures <strong>in</strong>creased with more leisure time <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1950s.C. Recent <strong>and</strong> current patterns of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong>C.1 Changes <strong>in</strong> Mexican <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> last 25 years.A brief analysis of state level data suggests how <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>nDesert has <strong>change</strong>d <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last few <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1970 agricultural census, <strong>the</strong> area of crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong>pasture has <strong>in</strong>creased, <strong>and</strong> forest cover has <strong>de</strong>creased. There have been significant <strong>change</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> crop mix,associated with <strong>change</strong>s <strong>in</strong> world markets <strong>and</strong> government subsidies. In <strong>the</strong> states of <strong>Chihuahua</strong> <strong>and</strong>Coahuila, <strong>the</strong> area <strong>in</strong> crops for human consumption has <strong>de</strong>creased by about 10%, whereas <strong>the</strong> area <strong>in</strong> forage,particularly oats <strong>and</strong> alfalfa, has <strong>in</strong>creased. Cotton acreage <strong>and</strong> wheat for export have <strong>de</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ed. In Sonora,<strong>the</strong> crop shift was from basic gra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> beans <strong>in</strong>to oilseeds, forage, <strong>and</strong> vegetables (Lorey, 1993)These <strong>change</strong>s are consistent with those <strong>de</strong>scribed by S<strong>and</strong>erson (1986) who analyzes <strong>the</strong> growth of<strong>the</strong> fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetable <strong>and</strong> livestock sectors. Never<strong>the</strong>less, large areas have been ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> wheat,maize <strong>and</strong> beans as a result of government subsidies, tradition, <strong>and</strong> lack access to water or credit foralternative crops.Redistribution of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> slowed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last couple of <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s, with few new ejidos established <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Mexican north. L<strong>and</strong> concentration <strong>in</strong>creased, often through <strong>the</strong> illegal rent<strong>in</strong>g of ejido <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s, especiallygraz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> irrigated area, to larger <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hol<strong>de</strong>rs.C.2.Current <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert

8The basis for analysis of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> overall <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert is <strong>the</strong> 1990 MexicanAgricultural census that reports <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> hold<strong>in</strong>g sizes <strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong> for each municipio (INEGI, 1995). The 1990census is consi<strong>de</strong>red relatively reliable <strong>and</strong> reports a wi<strong>de</strong> range of variables for several <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>g sizes<strong>and</strong> <strong>tenure</strong>s at <strong>the</strong> municipio level.For those municipios with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert <strong>the</strong> 1990 census reports an average percentageof <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> private <strong>tenure</strong> at about 65%, higher than <strong>the</strong> Mexico wi<strong>de</strong> average of 52%. In three-quarters of<strong>the</strong> municipios, more than half of all arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is privately owned. Ejido <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> statesof Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi, <strong>and</strong> Durango, where more than 40 percent of all <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is ejidal over much of<strong>the</strong> region (Figure 9). L<strong>and</strong> is more heavily concentrated <strong>in</strong> private h<strong>and</strong>s as one moves north with<strong>in</strong>Mexico, particularly with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>astern area of <strong>the</strong> bioregion. The percentage of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> private <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>ownership ranges from approximately 10 percent <strong>in</strong> Praxe<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> Guerrero, <strong>Chihuahua</strong> to 98.8 percent <strong>in</strong>Coronado, <strong>Chihuahua</strong>. State averages for private <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> ownership range from54 percent <strong>in</strong> Durango <strong>and</strong> SanLuis Potosi to a high of 84.9 percent <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (Table 1).In <strong>the</strong> bor<strong>de</strong>r areas, <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is primarily held <strong>in</strong> private ownership, where <strong>the</strong>re is a higher percentage ofejido <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn states of <strong>the</strong> region. High percentages of ejido ownership are found around <strong>the</strong>Mapimi, Cuatro Cienegas, <strong>and</strong> Cuenca <strong>de</strong>l Rio Nazas regions. “Mixed”? ejido <strong>and</strong> private ownershipaccounts for less than six percent of all productive <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert region of every state butZacatecas (10.9%) <strong>and</strong> Durango (9.4%).Table 1Private ownershipranges from lowest tohighest municipiowith<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state<strong>Chihuahua</strong> 9.1 to 98.8% 84.9Sonora 44.3 to 94.6% 76.8Coahuila 14.5 to 98.5% 73.9Nuevo Leon 46.8 to 94.6% 69.4Zacatecas 19.3 to 91% 59.3Durango 23.7 to 93% 54.7San Luis Potosi 11.8 to 78.2% 54.6Average formunicipios with<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> stateThe pattern of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> size distribution reflects, to some extent, that of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong>. Larger<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>gs are more predom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north (Figure 9), reflect<strong>in</strong>g larger <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> private h<strong>and</strong>sthan <strong>in</strong> ejidos. For <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert regions of Coahuila (58.75%), <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (60,.25%), <strong>and</strong> Sonora(85.52%), more than half of all arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is held <strong>in</strong> tracts of at least 2500 hectares.Very little <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is <strong>in</strong> small plots, traditionally <strong>de</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ed as less than 5 hectares. No municipio hasmore than 50% of all arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> small plots, <strong>and</strong> many have less than five percent of arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> held <strong>in</strong>plots of less than five hectares. Those that do have more small <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>gs tend to be <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnportion of <strong>the</strong> bioregion, particularly near <strong>the</strong> priority areas of Mapimi, Cuatro Ciénegas, Cuenca <strong>de</strong>l RioNazas, <strong>the</strong> Altiplano Mexicano Nororiental, <strong>and</strong> Huizache-Cerritos (Figure 11).The large <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north overlap with <strong>the</strong> region <strong>in</strong> which pasture is <strong>the</strong> most dom<strong>in</strong>antform of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong>: <strong>the</strong>re is an almost perfect one-to-one correlation between municipios with a large percentof <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> pasture <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority of plots of over 100 hectares.The implications of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>hold<strong>in</strong>g size for conservation are by no means clear <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r<strong>the</strong> United States or Mexico. Although some authors have claimed that ejido <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> tends to be <strong>in</strong>efficiently<strong>use</strong>d or overgrazed (Dovr<strong>in</strong>g, 1970; Mueller, 1970) o<strong>the</strong>rs suggest that many ejidos are productive <strong>and</strong>relatively benign <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir environmental impacts beca<strong>use</strong> of low <strong>use</strong> of chemical <strong>in</strong>puts or lack of capital for

9livestock (Tuckman, 1976; Nguyen, 1979. Whilst some large <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>owners leave <strong>the</strong>ir property relativelyun<strong>de</strong>r<strong>de</strong>veloped <strong>and</strong> wild, o<strong>the</strong>rs employ <strong>in</strong>tensive agricultural technologies or exceed <strong>the</strong> carry<strong>in</strong>g capacityof <strong>the</strong> range.C.3.Current <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> cover <strong>in</strong> MexicoThe 1990 INEGI census <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>s 24,429,582.25 hectares of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert. Ofthis area, 10% is reported as crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, 88% as open pasture, <strong>and</strong> less than 2% as forest (Figure 12). Itshould be noted that <strong>the</strong> agricultural census does not <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>the</strong> complete area of all Mexican states. Theseven states if <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert can grouped roughly <strong>in</strong>to three regions: <strong>the</strong> north, consist<strong>in</strong>g ofSonora, <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Coahuila 1 ; <strong>the</strong> central <strong>de</strong>sert, compris<strong>in</strong>g Durango <strong>and</strong> Nuevo Leon; <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> southconsist<strong>in</strong>g of Zacatecas <strong>and</strong> San Luis Potosi. L<strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> trends are relatively consistent across regions, butvary between <strong>the</strong>m.The greats percentages of crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south (Figure 13), while pasture<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s cover much of<strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn two-thirds of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert (Figure 14). The most heavily forested <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south <strong>and</strong> along<strong>the</strong> eastern <strong>and</strong> western edges of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert (Figure 15).In <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn states, <strong>the</strong> crop area is less than 6% of <strong>the</strong> total area (5.08% <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, 5.83% <strong>in</strong>Coahuila, <strong>and</strong> 2.18% <strong>in</strong> Sonora). In <strong>the</strong> central region, <strong>the</strong> percentage of crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong>creases toapproximately 20% (19.86% <strong>in</strong> Durango, 22.75% <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon). The greatest percentages of crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> are<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south, where it is over 30T of <strong>the</strong> total <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> area (30.89% <strong>in</strong> Zacatecas, 36.34% <strong>in</strong> San Luis Potosi).In some muncipios <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south, over 90% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> area is suitable for crops (Figure 13). Temperature<strong>and</strong> water availability are more favorable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north, where crops would need to adapt toextremes of temperature <strong>and</strong> would require extensive irrigation. Plots are also smaller <strong>and</strong> ejidal,suggest<strong>in</strong>g that more agriculture may be for home consumption <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south.The opposite is true of <strong>the</strong> percentage of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> natural pasture, which is greatest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north, whereit is well over 75% of <strong>the</strong> total <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> area (93.56% <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, 92.74% <strong>in</strong> Coahuila, <strong>and</strong> 97.74% <strong>in</strong>Sonora). Southwestern <strong>Chihuahua</strong> has slightly less than <strong>the</strong> state average <strong>in</strong> pasture, through pasture stillcovers over 80%. In <strong>the</strong> central region, <strong>the</strong> area <strong>in</strong> natural pasture <strong>de</strong>creases to 70-75% (70.35% <strong>in</strong>Durango, 75.58% <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon), <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south, it is less than 70% (68.55% <strong>in</strong> Zacatecas, 62.23% <strong>in</strong>San Luis Potosi). In general, <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn portions of <strong>the</strong>se states have higher percentages of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> pasturethan <strong>the</strong> south. Aga<strong>in</strong>, this is consistent with temperature <strong>and</strong> water availability as well as <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>tenure</strong>(Figure 14).The total area with forest (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g mixed forest <strong>and</strong> pasture) is less than 1% <strong>in</strong> most of <strong>the</strong> north<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> south (0.83% <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, 0.50% <strong>in</strong> Coahuila, 0.04% <strong>in</strong> Sonora, 0.24% <strong>in</strong> Zacatecas, <strong>and</strong> 0.33% <strong>in</strong>San Luis Potosi). In <strong>the</strong> central region, Durango has forest on 8.85% of its <strong>de</strong>sert <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s, while 1.44% of <strong>the</strong><strong>de</strong>sert <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s of Nuevo Leon conta<strong>in</strong> forest (Figure 15).C.4.Crop production <strong>in</strong> Mexican <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n DesertOf <strong>the</strong> general <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>use</strong> category of crop<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, about 60% was reported as actually sown with crops <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> 1990-91 period. Of <strong>the</strong> total area sown throughout <strong>the</strong> year, almost 90% grows annual crops, <strong>and</strong> 15%perennials. The total area actually sown with crops is greatest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn region, where it is over 68%of <strong>the</strong> arable area (78.74% <strong>in</strong> Zacatecas 68.57% <strong>in</strong> San Luis Potosi). With<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se states, cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> isgreatest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> western municipios. In <strong>the</strong> central region, it <strong>de</strong>creases to about 55-60% (60.85% <strong>in</strong> Durango,54.23% <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon), through <strong>the</strong> percentage of <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> that is cropped varies greatly between municipios,from less than 40% to over 78%. In <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn region (exclud<strong>in</strong>g Sonora), cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> is 45-50% of <strong>the</strong>total arable area (50.09% <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, 45.74% <strong>in</strong> Coahuila). Aga<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> state average does not show <strong>the</strong>1 The sou<strong>the</strong>rn part of Coahuila is more properly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central region, but beca<strong>use</strong> calculations are at <strong>the</strong> state level, we haveplaced all of Coahuila <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north.

10variance between municipios. Cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> ranges from less than 40% to more than 78% of <strong>the</strong> arablearea <strong>in</strong> this region. Sonora has <strong>the</strong> least cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, only 16.27% of <strong>the</strong> arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, though <strong>the</strong> municipioof Naco has over 41% of its arable <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> crops. Perennials are most prevalent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> irrigated areas of <strong>the</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn two-thirds of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert region. Twelve annual crops account for 88% of <strong>the</strong> total crops accountfor 88% of <strong>the</strong> total cropped area. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g-summer season, beans <strong>and</strong> maize comprise 42% <strong>and</strong>34%, respectively of <strong>the</strong> total area sown.Annual crops are particularly prevalent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south, though no municipio <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert bioregion hasless than 17% of its cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> sown with annuals. Throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert, <strong>the</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gsummerplant<strong>in</strong>g season is <strong>the</strong> most important. Beans <strong>and</strong> maize are <strong>the</strong> two major crops <strong>in</strong> all of <strong>the</strong> states,though beans are particularly important <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Durango <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> crop <strong>in</strong> bothZacatecas (70.73% of <strong>the</strong> total cropped area) <strong>and</strong> Durango (54.41%). In Durango <strong>the</strong>y are grown primarily<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn municipios In Zacatecas <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> San Luis Potosi, where <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> second-most importantcrop (43.32%), beans are grown particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> southwestern municipios. Beans are also <strong>the</strong> secondmost important crop <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon (15.69%), <strong>and</strong> Coahuila (13.66%). In Sonora, beans are <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> crop,though <strong>the</strong>y are planted on only 14.48% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. They are also an important crop <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (11.52%of <strong>the</strong> total cropped). However, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> municipios of <strong>Chihuahua</strong> <strong>and</strong> Aquiles Serdan, beans are planted onover 44% of <strong>the</strong> cropped area, rais<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> state average. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter season, beans are grownthroughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert, but <strong>in</strong> small amounts (less than 1%). W<strong>in</strong>ter production is primarily <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> eastern half of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert, as well as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> municipios of Agua Prieta <strong>and</strong> Bavispe <strong>in</strong> Sonora, <strong>and</strong> Janos<strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>.Maiz is <strong>the</strong> primary crop <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eastern states of Nuevo Leon (68.77% of <strong>the</strong> total cropped area),where it is grown primarily <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn municipios (Galeana, Doctor Arroyo, <strong>and</strong> Mier Y Noriega); <strong>and</strong>San Luis Potosi (68.51%), as well as <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn states of <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (28.09%), especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>municipios of Rosario, Satevó, <strong>and</strong> Valle <strong>de</strong> Zaragoza; <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Coahuila (30.67%) (Figure 16). In <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rthree states, maize is <strong>the</strong> second most important crop. It is grown on over 20% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> Durango(24.14%) <strong>and</strong> Zacatecas (21.10%), as well as on 11.75% of <strong>the</strong> cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> Sonora. In <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter,maize is important primarily <strong>in</strong> San Luis Potosi (4.20%), though it is also grown <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon, Sonora,<strong>and</strong> Coahuila.Cotton is grown almost exclusively <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north (Figure 17). It accounts for just over 12% of <strong>the</strong>total cropped area <strong>in</strong> both Coahuila (12.29%) <strong>and</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (12.42%), <strong>and</strong> 7.04% <strong>in</strong> Sonora. It is alsogrown <strong>in</strong> Durango (1.99%). In <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter cotton is grown <strong>in</strong> negligible amounts <strong>in</strong> Coahuila <strong>and</strong> Durango.Cotton production is significant for conservation beca<strong>use</strong> of <strong>the</strong> large amounts of pestici<strong>de</strong>s that tend t be<strong>use</strong>d on this commercial crop.Also important <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north is sorghum, which is planted on 7.63% of <strong>the</strong> cropped <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>in</strong> Sonora,6.81% <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>, <strong>and</strong> 4.72% <strong>in</strong> Coahuila. Sorghum is also planted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central states of Durango(2.53% <strong>and</strong> Nuevo Leon (1.97%). It is grown <strong>in</strong> small amounts (less than 1% <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same regions dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>and</strong> is ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>use</strong>d for animal feed.Oats are grown throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong>n Desert, particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> southwestern region (4.04% <strong>in</strong>Zacatecas, 2.70% <strong>in</strong> Durango) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north (2.06% <strong>in</strong> Sonora, 1.44% <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> <strong>and</strong> 1.28% <strong>in</strong>Coahuila). Most of <strong>the</strong> production occurs along <strong>the</strong> eastern <strong>and</strong> western edges of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>w<strong>in</strong>ter season, oats are an important crop <strong>in</strong> Sonora (10.70%) <strong>and</strong> Coahuila (3.20%) <strong>and</strong> are grown <strong>in</strong>smaller amounts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r states. They are also primarily for animal feed.Soybeans are grown only <strong>in</strong> summer <strong>and</strong> almost exclusively <strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (2.92%). Barley isplanted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central region (2.71% <strong>in</strong> Durango, 2.02 % <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon), particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> east <strong>and</strong> west;<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Sonora (1.45%). In <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter, barley becomes more important <strong>in</strong> Sonora (3.98% of <strong>the</strong> total areacropped throughout <strong>the</strong> year) <strong>and</strong> is grown <strong>in</strong> smaller amounts throughout <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>sert region,particularly <strong>the</strong> north.In <strong>the</strong> summer, wheat is planted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> central region (1.86% <strong>in</strong> Durango, 1.26% <strong>in</strong> Nuevo Leon) <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Chihuahua</strong> (1.66%). However, wheat is a more important crop dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter season (Figure 18). It is