2. Managing Mens Rea in Singapore - Singapore Academy of Law

2. Managing Mens Rea in Singapore - Singapore Academy of Law

2. Managing Mens Rea in Singapore - Singapore Academy of Law

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

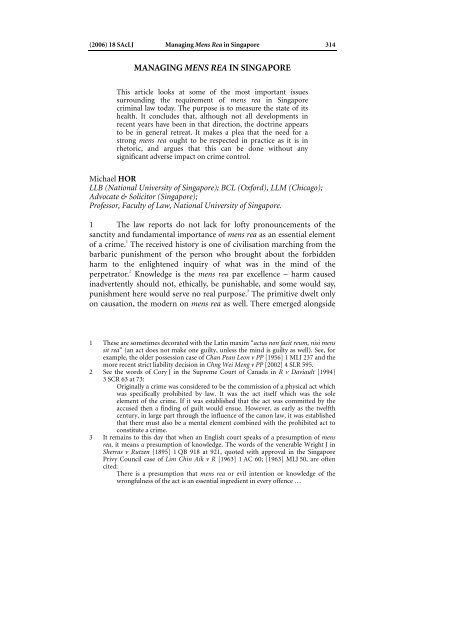

(2006) 18 SAcLJ <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 314MANAGING MENS REA IN SINGAPOREThis article looks at some <strong>of</strong> the most important issuessurround<strong>in</strong>g the requirement <strong>of</strong> mens rea <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gaporecrim<strong>in</strong>al law today. The purpose is to measure the state <strong>of</strong> itshealth. It concludes that, although not all developments <strong>in</strong>recent years have been <strong>in</strong> that direction, the doctr<strong>in</strong>e appearsto be <strong>in</strong> general retreat. It makes a plea that the need for astrong mens rea ought to be respected <strong>in</strong> practice as it is <strong>in</strong>rhetoric, and argues that this can be done without anysignificant adverse impact on crime control.Michael HORLLB (National University <strong>of</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore); BCL (Oxford), LLM (Chicago);Advocate & Solicitor (S<strong>in</strong>gapore);Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Faculty <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong>, National University <strong>of</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore.1 The law reports do not lack for l<strong>of</strong>ty pronouncements <strong>of</strong> thesanctity and fundamental importance <strong>of</strong> mens rea as an essential element<strong>of</strong> a crime. 1 The received history is one <strong>of</strong> civilisation march<strong>in</strong>g from thebarbaric punishment <strong>of</strong> the person who brought about the forbiddenharm to the enlightened <strong>in</strong>quiry <strong>of</strong> what was <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> theperpetrator. 2Knowledge is the mens rea par excellence – harm caused<strong>in</strong>advertently should not, ethically, be punishable, and some would say,punishment here would serve no real purpose. 3 The primitive dwelt onlyon causation, the modern on mens rea as well. There emerged alongside1 These are sometimes decorated with the Lat<strong>in</strong> maxim “actus non facit reum, nisi menssit rea” (an act does not make one guilty, unless the m<strong>in</strong>d is guilty as well). See, forexample, the older possession case <strong>of</strong> Chan Pean Leon v PP [1956] 1 MLJ 237 and themore recent strict liability decision <strong>in</strong> Chng Wei Meng v PP [2002] 4 SLR 595.2 See the words <strong>of</strong> Cory J <strong>in</strong> the Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Canada <strong>in</strong> R v Daviault [1994]3 SCR 63 at 73:Orig<strong>in</strong>ally a crime was considered to be the commission <strong>of</strong> a physical act whichwas specifically prohibited by law. It was the act itself which was the soleelement <strong>of</strong> the crime. If it was established that the act was committed by theaccused then a f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> guilt would ensue. However, as early as the twelfthcentury, <strong>in</strong> large part through the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> the canon law, it was establishedthat there must also be a mental element comb<strong>in</strong>ed with the prohibited act toconstitute a crime.3 It rema<strong>in</strong>s to this day that when an English court speaks <strong>of</strong> a presumption <strong>of</strong> mensrea, it means a presumption <strong>of</strong> knowledge. The words <strong>of</strong> the venerable Wright J <strong>in</strong>Sherras v Rutzen [1895] 1 QB 918 at 921, quoted with approval <strong>in</strong> the S<strong>in</strong>gaporePrivy Council case <strong>of</strong> Lim Ch<strong>in</strong> Aik v R [1963] 1 AC 60; [1963] MLJ 50, are <strong>of</strong>tencited:There is a presumption that mens rea or evil <strong>in</strong>tention or knowledge <strong>of</strong> thewrongfulness <strong>of</strong> the act is an essential <strong>in</strong>gredient <strong>in</strong> every <strong>of</strong>fence …

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 315mens rea another icon – the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that guilt, and therefore mens rea,must be proved by the prosecution beyond reasonable doubt. 4 The realityis someth<strong>in</strong>g else. There are <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>of</strong>fences for which the prosecutionmust prove mens rea beyond reasonable doubt. 5There are however agrow<strong>in</strong>g number <strong>of</strong> significant crimes which do not require fullknowledge: crimes which need only some lesser form <strong>of</strong> mens rea likenegligence; crimes which apparently require no mens rea at all; crimeswhich presume knowledge or negligence and require the accused personto disprove it. There cannot be any doubt that <strong>in</strong>fluential players <strong>in</strong> thecrim<strong>in</strong>al process – legislators, judges, prosecutors – harbour a dist<strong>in</strong>ctbelief that both the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> mens rea and <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> beyond reasonabledoubt are undesirable <strong>in</strong> a great many contexts. Yet it would be wrong tosay that either pr<strong>in</strong>ciple has been abandoned entirely. I hope to chart theebb and flow <strong>of</strong> allegiance to the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> mens rea and to discern theforces which push and pull one way or the other.I. Know<strong>in</strong>g me, know<strong>in</strong>g you: The mens rea <strong>of</strong> murder2 One <strong>of</strong> the most endur<strong>in</strong>g thorns <strong>in</strong> the flesh <strong>of</strong> the crim<strong>in</strong>al lawis s 300(c) <strong>of</strong> the Penal Code 6 which sets out the mens rea required for theonly k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> murder that reta<strong>in</strong>s any practical relevance. It is necessary toset out all the mens rea limbs <strong>of</strong> murder <strong>in</strong> order to appreciate the<strong>in</strong>terpretational difficulties:culpable homicide is murder —(a) if the act by which the death is caused is done with the<strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g death;(b) if it is done with the <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g such bodily <strong>in</strong>jury asthe <strong>of</strong>fender knows to be likely to cause the death <strong>of</strong> the person to whomthe harm is caused;(c) if it is done with the <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g bodily <strong>in</strong>jury to anyperson, and the bodily <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong>tended to be <strong>in</strong>flicted is sufficient <strong>in</strong>the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature to cause death; or4 I explore this <strong>in</strong> some detail <strong>in</strong> Michael Hor, “The Burden <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong> Crim<strong>in</strong>alJustice” (1992) 4 SAcLJ 267, and Michael Hor, “The Presumption <strong>of</strong> Innocence: AConstitutional Discourse for S<strong>in</strong>gapore” [1995] S<strong>in</strong>g JLS 365.5 A perusal <strong>of</strong> the Penal Code (Cap 224, 1985 Rev Ed) will bear this out.6 See prior treatments <strong>in</strong> Victor V Ramraj, “Murder Without an Intention to Kill”[2000] S<strong>in</strong>g JLS 560, and M Sornarajah, “The Def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> Murder Under the PenalCode” [1994] S<strong>in</strong>g JLS 1.

316S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)(d) if the person committ<strong>in</strong>g the act knows that it is so imm<strong>in</strong>entlydangerous that it must <strong>in</strong> all probability cause death, or such bodily<strong>in</strong>jury as is likely to cause death, and commits such act without anyexcuse for <strong>in</strong>curr<strong>in</strong>g the risk <strong>of</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g death, or such <strong>in</strong>jury asaforesaid.[emphasis added]3 Section 302 demonstrates what is at stake:Whoever commits murder shall be punished with death.4 Section 300(c) sticks out like a sore thumb. The other limbs l<strong>in</strong>kthe mens rea directly to the harm caused – death must be <strong>in</strong>tended orknown to be likely. Section 300(c) stops short <strong>of</strong> that – no doubt the<strong>in</strong>jury must have been <strong>in</strong>tended, but there is no apparent requirementthat the likelihood <strong>of</strong> death must be known or foreseen. This flouts theclassic conception <strong>of</strong> mens rea – if the accused person is to be heldaccountable for the death, as opposed to just the <strong>in</strong>jury, he or she must beproved to have known that death would be likely to ensue. The gravamen<strong>of</strong> murder is surely that the accused person chose to embark on a course<strong>of</strong> conduct, know<strong>in</strong>g that death (and noth<strong>in</strong>g less) would be the likelyresult. The chill<strong>in</strong>g s 302 prescribes one, and only one, punishment formurder: death. No sentenc<strong>in</strong>g discretion is needed for the crime is <strong>of</strong> thehighest order: the know<strong>in</strong>g deprivation <strong>of</strong> human life.5 It is surpris<strong>in</strong>g that there is little evidence that s 300(c) wasnoticed until relatively recently. For decades after the promulgation <strong>of</strong> thePenal Code, there seems to have been no consciousness that s 300(c)conta<strong>in</strong>ed the seeds <strong>of</strong> a highly subversive idea. 7 Prosecutions proceeded7 The Penal Code was promulgated <strong>in</strong> 1871 and came <strong>in</strong>to force a year later <strong>in</strong> theStraits Settlements (<strong>of</strong> which S<strong>in</strong>gapore was a prom<strong>in</strong>ent part), but murderprosecutions for decades after that seemed to adopt a studied ignorance <strong>of</strong> s 300(c)and appeared to assume that an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause death was <strong>in</strong>variably required.See, for example, R v Ong Choon [1938] MLJ 227, the Court <strong>of</strong> Crim<strong>in</strong>al Appeal <strong>of</strong>the Straits Settlements quoted this jury direction <strong>of</strong> the trial judge without censure:He was <strong>in</strong>tend<strong>in</strong>g to do someth<strong>in</strong>g and his <strong>in</strong>tention must be considered by hisconduct: whether he had a murderous <strong>in</strong>tention or whether he had simply an<strong>in</strong>tention to do a m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>jury or whether he had an <strong>in</strong>tention to killSo tenacious was this assumption that well <strong>in</strong>to the era <strong>of</strong> s 300(c) awareness, and ona s 300(c) charge, a trial court could say, <strong>in</strong> PP v Ow Ah Cheng [1992] 1 SLR 797 at805, [42]:We considered carefully whether the acts and <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> the accused on thatfateful day would constitute murder with<strong>in</strong> s 300(c) <strong>of</strong> the Code. It was f<strong>in</strong>allydecided that the evidence adduced was not consistent only with murder. Thefact that the deceased was strangled did not prove beyond a reasonable doubtthat the accused <strong>in</strong>tended to cause the death <strong>of</strong> Ah Lian.

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 317on the assumption that an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause death (and perhaps its closeally knowledge that death was likely) was required. 8 Then the dam broke.In 1956 the Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> India <strong>in</strong> Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh v The State <strong>of</strong> Punjabdecided to take s 300(c) at its word: 9Once the <strong>in</strong>tention to cause the bodily <strong>in</strong>jury actually found to bepresent is proved, the rest <strong>of</strong> the enquiry is purely objective and the onlyquestion is whether, as a matter <strong>of</strong> purely objective <strong>in</strong>ference, the <strong>in</strong>juryis sufficient <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature to cause death. No one hasa licence to run around <strong>in</strong>flict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>juries that are sufficient to causedeath <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature and claim that they are not guilty<strong>of</strong> murder. If they <strong>in</strong>flict <strong>in</strong>juries <strong>of</strong> that k<strong>in</strong>d, they must face theconsequences; and they can only escape if it can be shown, orreasonably deduced that the <strong>in</strong>jury was accidental or otherwiseun<strong>in</strong>tentional … The question is not whether the prisoner <strong>in</strong>tended to<strong>in</strong>flict a serious <strong>in</strong>jury or a trivial one … Whether he knew <strong>of</strong> itsseriousness, or <strong>in</strong>tended serious consequences, is neither here nor there.The question, so far as the <strong>in</strong>tention is concerned, is not whether he<strong>in</strong>tended to kill, or to <strong>in</strong>flict an <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>of</strong> a particular degree <strong>of</strong>seriousness.6 The element <strong>of</strong> death, thus reduced to an objective <strong>in</strong>quiry, isbanished from the realm <strong>of</strong> mens rea. It is difficult to imag<strong>in</strong>e how thisobjective <strong>in</strong>quiry is different from the causation <strong>in</strong>quiry <strong>of</strong> whether theaccused had caused death <strong>in</strong> the first place. If the assailant has caused an<strong>in</strong>jury, and that <strong>in</strong>jury leads to death, it can never be that the <strong>in</strong>jury wasnot sufficient <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature to lead to death. 107 The only question is whether the accused <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>flict the<strong>in</strong>jury which turned out to be fatal – death may have been far from them<strong>in</strong>d. It is important to appreciate the difference between s 300(c) andwhat I have called the classical conception that there must be knowledge<strong>of</strong> the likelihood <strong>of</strong> death. Too much is sometimes made <strong>of</strong> it. It is truethat <strong>in</strong> practical terms a requirement <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause anobjectively fatal <strong>in</strong>jury will <strong>of</strong>ten yield the same result as a requirement <strong>of</strong>8 For example, Hashim b<strong>in</strong> Mat Isa v PP [1950] MLJ 94.9 AIR 1958 SC 465 (“Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh”). This Indian decision was brought <strong>in</strong>to localconsciousness by the case <strong>of</strong> Wong Mimi v PP [1972–1974] SLR 73 and has nevers<strong>in</strong>ce been doubted. Curiously, the adoption <strong>of</strong> Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh was not quite necessaryfor the decision as the judges were disposed to f<strong>in</strong>d that there was an <strong>in</strong>tention tokill.10 I exclude from consideration cases <strong>of</strong> special susceptibility where, for example, ahaemophiliac dies <strong>of</strong> excessive bleed<strong>in</strong>g from an <strong>in</strong>flicted wound <strong>in</strong> circumstanceswhere a person not suffer<strong>in</strong>g from that disorder would not have died. Section 300(b)specifically provides that <strong>in</strong> such circumstances, to be guilty <strong>of</strong> murder, the assailantmust have actually known <strong>of</strong> the disorder.

318S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)knowledge that death was likely – death is normally the result <strong>of</strong> serious<strong>in</strong>juries and it is not an unfair assumption that most people must knowwhat serious <strong>in</strong>juries are and that they are likely to cause death. Yet thecrim<strong>in</strong>al law should not be based entirely on what is normally the case orwhat most people must know – death sometimes occurs from <strong>in</strong>jurieswhich are not normally thought <strong>of</strong> as serious, and many people do notknow this. A stab to the heart, adm<strong>in</strong>istered with significant force willnormally satisfy either requirement, unless the accused is able to showthat it was accidental, <strong>in</strong> the sense that the accused <strong>in</strong>tended no <strong>in</strong>jury atall or that another non-fatal <strong>in</strong>jury was <strong>in</strong>tended. But what does one dowith an accused who presses a pillow onto the face <strong>of</strong> a victim <strong>in</strong> order tosilence and not to kill, or an accused who slashes the leg <strong>of</strong> a victim <strong>in</strong>order to prevent escape and not to kill? Section 300(c) has the potential tomake these situations murder and punishable with death, and it is <strong>in</strong>cases like these that s 300(c) is subjected to the greatest stress.8 To the credit <strong>of</strong> our judges, they have extended a lifel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> aremarkable series <strong>of</strong> cases. This the courts achieved through the device <strong>of</strong>subtle dist<strong>in</strong>ctions between the <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong>tended and the <strong>in</strong>jury whichf<strong>in</strong>ally caused death. Embedded <strong>in</strong> s 300(c) is an <strong>in</strong>herent ambiguity: it ismurder only if the <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong>tended was the same as the fatal <strong>in</strong>jury. Thisuncerta<strong>in</strong>ty was anticipated <strong>in</strong> Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh: 11In consider<strong>in</strong>g whether the <strong>in</strong>tention was to <strong>in</strong>flict the <strong>in</strong>jury found tohave been <strong>in</strong>flicted, the enquiry necessarily proceeds on broad l<strong>in</strong>es as,for example, whether there was an <strong>in</strong>tention to strike at a vital or adangerous spot, and whether with sufficient force to cause the k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>jury found to have been <strong>in</strong>flicted. It is, <strong>of</strong> course, not necessary toenquire <strong>in</strong>to every last detail as, for <strong>in</strong>stance, whether the prisoner<strong>in</strong>tended to have the bowels fall out, or whether he <strong>in</strong>tended topenetrate the liver or the kidneys or the heart. Otherwise, a man whohas no knowledge <strong>of</strong> anatomy could never be convicted, for, if he doesnot know that there is a heart or a kidney or bowels, be cannot be saidto have <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>jure them. Of course, that is not the k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong>enquiry. It is broad based and simple and based on common sense: thek<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> enquiry that "twelve good men and true” could readilyappreciate and understand.9 The problem with this k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction is that it does not tellus exactly how particular the <strong>in</strong>tention must be. It is <strong>of</strong>ten that <strong>in</strong>juryleads to death <strong>in</strong> a cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> events – <strong>in</strong>cision, severance <strong>of</strong> artery, loss <strong>of</strong>blood, death. Although it seems clear that death need not be11 Supra n 9, at 467.

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 319contemplated, it is not clear precisely how far along the cha<strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>tention must extend. The courts have used this device spar<strong>in</strong>gly butspectacularly. In Mohamed Yas<strong>in</strong> b<strong>in</strong> Hus<strong>in</strong> v PP, 12the Privy Councilsurprised the legal community by quash<strong>in</strong>g a murder conviction whichhad been upheld <strong>in</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal. In the course <strong>of</strong> robbery andrape, Yas<strong>in</strong> had sat on the chest <strong>of</strong> his 58-year-old victim <strong>in</strong> order tosubdue her. This resulted <strong>in</strong> multiple rib fractures, shock, cardiac arrestand death. The uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty at the core <strong>of</strong> 300(c) was exploited to thefull: 13In the <strong>in</strong>stant case, the act <strong>of</strong> the appellant which caused the death, vizsitt<strong>in</strong>g forcibly on the victim’s chest, was voluntary on his part. He knewwhat he was do<strong>in</strong>g; he meant to do it; it was not accidental orun<strong>in</strong>tentional. This, however, is only the first step … Not only must theact <strong>of</strong> the accused which caused the death be voluntary <strong>in</strong> this sense; theprosecution must also prove that the accused <strong>in</strong>tended, by do<strong>in</strong>g it, tocause some bodily <strong>in</strong>jury to the victim <strong>of</strong> a k<strong>in</strong>d which is sufficient <strong>in</strong>the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature to cause death.…[I]t would not have been necessary for the trial judges <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stant case toenter <strong>in</strong>to an enquiry whether the appellant <strong>in</strong>tended to cause the precise<strong>in</strong>juries which <strong>in</strong> fact resulted or had sufficient knowledge <strong>of</strong> anatomyto know that the <strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>in</strong>jury which might result from his act … Itwas, however, essential for the prosecution to prove, at very least, thatthe appellant did <strong>in</strong>tend by sitt<strong>in</strong>g on the victim’s chest to <strong>in</strong>flict upon hersome <strong>in</strong>ternal, as dist<strong>in</strong>ct from mere superficial, <strong>in</strong>juries or temporary pa<strong>in</strong>[for which there was no evidence].[emphasis added]10 It would have been unexceptionable if Yas<strong>in</strong> had landed on hisvictim’s chest accidentally, perhaps as a result <strong>of</strong> tripp<strong>in</strong>g oversometh<strong>in</strong>g. 14It would have also been uncontroversial if Yas<strong>in</strong> had<strong>in</strong>tended a wholly different <strong>in</strong>jury, for example, if he <strong>in</strong>tended to sit onthe victim’s arm but missed the target and sat on her chest <strong>in</strong>stead. Thenovelty here was that the court was will<strong>in</strong>g to use this device <strong>in</strong> asituation where the accused had “voluntarily” set <strong>of</strong>f a cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> eventswhich led <strong>in</strong>exorably to death. Yas<strong>in</strong> had set about to sit on her chest andto do that with a degree <strong>of</strong> force which was (objectively) sufficient t<strong>of</strong>racture her ribs – and that is exactly what happened. The Privy Council12 [1975–1977] SLR 34 (PC) (“Yas<strong>in</strong>”), [1972–1974] SLR 263 (CA).13 Yas<strong>in</strong>, id, at 36–37, [8] and [11]–[12].14 As was the case <strong>in</strong> PP v Abdul Nasir b<strong>in</strong> Amer Hamsah [1996] SGHC 138.

320S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)had <strong>in</strong>dulged <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>quiry which it had itself seemed to deny wasnecessary – the acquittal was <strong>in</strong> fact based on a lack <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tention tocause the “precise <strong>in</strong>juries” which f<strong>in</strong>ally killed the victim. The courts <strong>of</strong>S<strong>in</strong>gapore were thrown <strong>in</strong> confusion. In a case that followed shortly, PP vVisuvanathan, 15the High Court quickly sought to restore the former“broad” <strong>in</strong>quiry by feebly attempt<strong>in</strong>g to expla<strong>in</strong> away the Privy Council,say<strong>in</strong>g that while the “precise <strong>in</strong>jury” approach was “factuallyappropriate”, it was not “<strong>of</strong> universal application” – it was never spelt outwhy it was appropriate on the facts <strong>in</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong>, nor was it expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> whatcircumstances it is appropriate and <strong>in</strong> what others it is not. 16 When thematter went up to the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal, Yas<strong>in</strong> was simply ignored as if ithad never been decided. 1711 Technically, neither Yas<strong>in</strong> nor Visuvanathnan are clearly <strong>in</strong> theright or <strong>in</strong> the wrong. The ambiguity is <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> the formulation <strong>of</strong>s 300(c). This uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty created a discretion <strong>in</strong> the courts to broaden ornarrow the subjective <strong>in</strong>quiry. What the decisions do not tell us explicitlyis when the discretion will be exercised one way or the other. It is <strong>of</strong>course hazardous to aspire to clairvoyance, but it is difficult to resist thespeculation that the controll<strong>in</strong>g factor is someth<strong>in</strong>g which every courts<strong>in</strong>ce Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh has declared to be taboo under s 300(c) – that <strong>of</strong>whether the accused contemplated death when he or she embarked onthe violent enterprise. 1812 Two other children <strong>of</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong> seem to bear this out. In PP v Ow AhCheng, 19 the accused was <strong>in</strong> the course <strong>of</strong> committ<strong>in</strong>g theft when he wassurprised by a 14-year-old girl. Ow subdued her and pressed a pillowonto her face <strong>in</strong> order to prevent her from shout<strong>in</strong>g. She died <strong>of</strong>asphyxiation. The High Court granted a rare acquittal <strong>in</strong> these terms: 20The question was whether the degree <strong>of</strong> force used was so extreme as tobe consistent only with an <strong>in</strong>tent to cause bodily <strong>in</strong>jury, and the bodily<strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong>tended to be <strong>in</strong>flicted was sufficient <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong>nature to cause death. If the accused wanted to kill Ah Lian, the pressure15 [1975–1977] SLR 564 (“Visuvanathan”).16 Id at 568, [14].17 Visuvanathan v PP [1978–1979] SLR 49.18 For a recent declaration, see Tan Chee Wee v PP [2004] 1 SLR 479 at [42]:Section 300(c) thus envisions that the accused subjectively <strong>in</strong>tends to cause abodily <strong>in</strong>jury that is objectively likely to cause death <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong>nature. There is no necessity for the accused to have considered whether or notthe <strong>in</strong>jury to be <strong>in</strong>flicted would have such a result.19 Supra n 7 (“Ow Ah Cheng”).20 Id, at 804–805, [36].

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 321that he would have applied to the larynx would have <strong>in</strong> all likelihoodresulted <strong>in</strong> a fracture <strong>of</strong> the larynx or more serious <strong>in</strong>juries. The degree<strong>of</strong> force used would have been extreme as to be consistent only with an<strong>in</strong>tent to do serious harm. [emphasis added]13 Aga<strong>in</strong>, as <strong>in</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong>, there was noth<strong>in</strong>g particularly accidental aboutthe whole affair, but the court was persuaded to <strong>in</strong>voke the “precise<strong>in</strong>tention” approach – Ow may have <strong>in</strong>tended to cause superficial <strong>in</strong>juriesto the face, but probably <strong>in</strong>tended no more than that. Though it mayappear curious that Yas<strong>in</strong> was never mentioned, the mystery dissolveswhen we consider that the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal <strong>in</strong> a then-recent decision, TanCheow Bok v PP, had apparently denounced Yas<strong>in</strong> when it was pressedupon the court on rather similar facts. 21 In the course <strong>of</strong> a robbery, Tansubdued his victim. In order to prevent the victim from shout<strong>in</strong>g he stucka knife <strong>in</strong>to her mouth. A particularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g facet <strong>of</strong> this case was theunchallenged forensic evidence that it was actually quite difficult to killsomeone that way – what happened was that the knife had entered themouth at a specific angle, gone through a narrow passage between thevertebra and the skull, and had severed the vertebral artery, lead<strong>in</strong>g tobleed<strong>in</strong>g and death. At any other angle, the knife would have struck theskull or the vertebra, but the <strong>in</strong>jury would not have been fatal. The Court<strong>of</strong> Appeal, <strong>in</strong> convict<strong>in</strong>g the accused <strong>of</strong> murder, expressly approved theHigh Court decision <strong>in</strong> Visuvanathan and refused to use the “precise<strong>in</strong>jury” approach. The judges <strong>in</strong> Ow Ah Cheng wanted to do the oppositeand could not very well do so openly, and so soon after the Court <strong>of</strong>Appeal had spoken <strong>in</strong> Tan Cheow Bok. The question is why the court <strong>in</strong>Ow Ah Cheng decided to use the “precise <strong>in</strong>jury” device when the judges<strong>in</strong> Tan Cheow Bok refused. The only sensible dist<strong>in</strong>ction is the <strong>in</strong>strument<strong>of</strong> the kill<strong>in</strong>g – one was a knife, the other a pillow. Inst<strong>in</strong>ctively that oughtto be a material difference, but exactly why should it be so? The onlysensible reason is that an accused who uses a knife is more likely to havecontemplated that death would be the result <strong>of</strong> his or her actions. Thus <strong>in</strong>Tan Cheow Bok, even though the objective likelihood <strong>of</strong> death result<strong>in</strong>gfrom the knife be<strong>in</strong>g lodged <strong>in</strong> the mouth <strong>of</strong> the victim was small, thatpiece <strong>of</strong> forensic <strong>in</strong>telligence would probably not have been <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d<strong>of</strong> the accused – he would have been likely to have contemplated death.On the other hand, what the pillow-wield<strong>in</strong>g accused did <strong>in</strong> Ow Ah Chengwas the opposite – it was probably someth<strong>in</strong>g very dangerous to <strong>in</strong>dulge<strong>in</strong>, but that was not immediately obvious to the untra<strong>in</strong>ed m<strong>in</strong>d. It wasplausible that the accused did not have death on his m<strong>in</strong>d. A similar21 [1991] SLR 293 at 301–302, [32]–[33] (“Tan Cheow Bock”).

322S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)sentiment must have operated on the Privy Council <strong>in</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong> itself –sitt<strong>in</strong>g on the chest <strong>of</strong> a 58-year-old woman with a degree <strong>of</strong> force wasobjectively a potentially lethal th<strong>in</strong>g to do, but that would not have beenapparent to a layperson: 22[T]o fall on someone’s chest, even forcibly, is someth<strong>in</strong>g which occursfrequently <strong>in</strong> many ord<strong>in</strong>ary sports, such as rugby football, and thoughit may cause temporary pa<strong>in</strong>, it is most unusual for it to result <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal<strong>in</strong>juries at all, let alone fatal <strong>in</strong>juries. [emphasis added]14 The Privy Council could not possibly have been pronounc<strong>in</strong>g onthe objective forensic position – there was no expert evidence on recordfor the court to do that legitimately. What the court was more likely tohave <strong>in</strong>tended to say is that the ord<strong>in</strong>ary untra<strong>in</strong>ed layperson, as theaccused person <strong>in</strong> that case was likely to be, would probably not havecontemplated that sitt<strong>in</strong>g on the chest would have fatal consequences.15 The judicial choice between the broad and precise <strong>in</strong>juryapproaches was faced rather more squarely <strong>in</strong> another decision <strong>of</strong> theHigh Court. In PP v Lim Poh Lye, 23 it was yet another robbery attempt andthe accused had slashed the leg <strong>of</strong> the victim <strong>in</strong> order to prevent himfrom escap<strong>in</strong>g. The femoral ve<strong>in</strong> was severed and the victim died fromloss <strong>of</strong> blood. The accused was acquitted <strong>of</strong> murder, but aga<strong>in</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong> wasnot mentioned at all. Instead the High Court relied on an earlier decision<strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal, PP v Tan Chee Hwee 24 <strong>in</strong> this manner: 25But the crucial question was whether Lim <strong>in</strong>tended to cause those<strong>in</strong>juries, that is, the stab wounds, and not whether he <strong>in</strong>tended to kill.Follow<strong>in</strong>g Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh, the answer would certa<strong>in</strong>ly be “yes”, andconsequently, the accused would be guilty <strong>of</strong> murder should his victimdie from that <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong>jury. Tan Chee Hwee, however, ameliorates anaccidental specific <strong>in</strong>jury (asphyxia) if the <strong>in</strong>tended act (strangulation)was <strong>in</strong>flicted without an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause mortal <strong>in</strong>jury [but for] aspecific non-fatal purpose…[This exception to Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh] would not, <strong>in</strong>my view … apply where an assailant stabs another <strong>in</strong> a vulnerable orsensitive region <strong>of</strong> the body, such as the chest, and claims that he did soto prevent escape. [emphasis added]16 This decision, probably the most significant <strong>in</strong> the field s<strong>in</strong>ceYas<strong>in</strong>, was the first to openly recognise that there is a problem with22 Supra n 12, at 37, [10].23 [2005] 2 SLR 130 (“Lim Poh Lye”).24 [1993] 2 SLR 657 (“Tan Chee Hwee”).25 Supra n 23, at [15].

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 323s 300(c). 26The earlier cases, and Yas<strong>in</strong> itself, had pretended that it wasbus<strong>in</strong>ess as usual. Lim Poh Lye has its difficulties. The failure to mentionYas<strong>in</strong> might have been understandable, given the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal’sdeclared distaste for it, but the reliance on Tan Chee Hwee is technicallymisplaced. In that case, what started <strong>of</strong>f as theft turned disastrous whenthe maid <strong>of</strong> the house returned unexpectedly and surprised the accusedand his confederates. In the ensu<strong>in</strong>g struggle, the maid was strangled todeath by the cord <strong>of</strong> an electric iron wound round her neck. The accusedwas acquitted because the Court had made a f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> fact that theaccused persons had only <strong>in</strong>tended to tie her up (around the torso) withthe cord, but <strong>in</strong> the course <strong>of</strong> the struggle, the cord had accidentallyslipped <strong>of</strong>f the torso and onto her neck: 27In the circumstances we are driven to the conclusion that the <strong>in</strong>jurywhich was <strong>in</strong> fact caused to the maid around her neck, <strong>in</strong> all probability,was not <strong>in</strong>tentionally but accidentally or un<strong>in</strong>tentionally caused.[emphasis added]17 Thus, so the court found, while <strong>in</strong>juries to her torso might havebeen <strong>in</strong>tended, those “around her neck” were not. The enterprise whichthe accused persons had embarked upon, ie, ty<strong>in</strong>g the victim up aroundthe torso, would not have resulted <strong>in</strong> death. The factual situation wasmaterially dissimilar, and would have been analogous only if the court <strong>in</strong>Tan Chee Hwee had found that the accused persons <strong>in</strong>tended to w<strong>in</strong>d thecord round the victim’s neck, but had not <strong>in</strong>tended anyth<strong>in</strong>g more thanto silence her. There were conflict<strong>in</strong>g statements given to the police aboutwhether the accused persons had <strong>in</strong>tended to w<strong>in</strong>d the cord round thevictim’s neck, and <strong>in</strong> the circumstances the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal had given the26 To be fair, the earlier decision <strong>of</strong> the High Court <strong>in</strong> PP v Sundarti Supriyanto [2004]4 SLR 622 had adopted the views <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong> Stanley Yeo <strong>in</strong> “Academic Contributionsand Judicial Interpretations <strong>of</strong> Section 300(c) Murder” S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Law</strong> Gazette (April2004), p 21, <strong>in</strong> characteris<strong>in</strong>g the predom<strong>in</strong>ant judicial approach as “very muchobjective” and describ<strong>in</strong>g it as follows, at [129]:[E]ven if an accused <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>flict only a m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>jury, it was sufficient toresult <strong>in</strong> a conviction for murder so long as the <strong>in</strong>jury actually <strong>in</strong>flicted wassufficient <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature to cause death. [emphasis <strong>in</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al]This analysis accuses the court <strong>of</strong> ignor<strong>in</strong>g the difference between <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong>juryand actual <strong>in</strong>jury, and declares that this is not faithful to Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh, which requireda precise correspondence between <strong>in</strong>tended and actual <strong>in</strong>jury. Although this thesisstems from the genu<strong>in</strong>e feel<strong>in</strong>g that someth<strong>in</strong>g is amiss with s 300(c), I do not th<strong>in</strong>kthat the court has ever denied that there must be a certa<strong>in</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> correspondencebetween the <strong>in</strong>tended and actual <strong>in</strong>jury. As I have argued, that there need not beabsolute correspondence is expressed <strong>in</strong> Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh itself. The real dispute has notbeen with respect to whether or not there should or should not be correspondence,but with the degree <strong>of</strong> correspondence that would suffice.27 Supra n 24, at 668, [46].

324S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)accused persons the benefit <strong>of</strong> the doubt. 28 The true ancestor <strong>of</strong> Lim PohLye is not Tan Chee Hwee, but Yas<strong>in</strong>, which has never been overruled.18 It is also unfortunate that Lim Poh Lye formulates the position <strong>in</strong>the form <strong>of</strong> rule and exception – Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh is the rule, Tan Chee Hweethe exception. The danger is that this assumes that Tan Chee Hwee is<strong>in</strong>consistent with Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh (otherwise an exception would not beneeded), and this <strong>in</strong>vites future courts to f<strong>in</strong>d fault with it. It would havebeen safer to expla<strong>in</strong> the situation as be<strong>in</strong>g the result <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>herentuncerta<strong>in</strong>ty embodied <strong>in</strong> s 300(c) itself, for the section does not say withwhat particularity the fatal <strong>in</strong>jury must have been <strong>in</strong>tended. Neither is therule or the exception, but both are faithful to s 300(c).19 That said, Lim Poh Lye does not expla<strong>in</strong> why a “non-fatalpurpose” should ameliorate the “accidental specific <strong>in</strong>jury”. Nor does itexpla<strong>in</strong> why the amelioration should not operate if the <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong>juryhad been to a “vulnerable or sensitive region <strong>of</strong> the body”. Aga<strong>in</strong>, theunexpressed rationale must be the <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ct that it does matter whether theaccused had contemplated death when he or she acted. Thus, where thereis a non-fatal purpose, the likelihood <strong>of</strong> death be<strong>in</strong>g contemplated issmall – the “exception” should apply to relieve the accused <strong>of</strong> murder.Where the <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong>jury is to a vulnerable part <strong>of</strong> the body, it is likelythat death was either <strong>in</strong>tended or known to be the result. Lim Poh Lyegoes too far if it implies that these are hard and fast rules – a non-fatalpurpose is not necessarily <strong>in</strong>consistent with knowledge <strong>of</strong> lethality,neither is an <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong>jury to a vulnerable part <strong>of</strong> the body dispositive<strong>of</strong> such knowledge. Yet one can readily sympathise with the judge <strong>in</strong> LimPoh Lye for not be<strong>in</strong>g explicit – this is the very <strong>in</strong>quiry which all theauthorities say is not to be embarked upon.20 This then is the core <strong>of</strong> the problem. Section 300(c)’s only reasonfor existence is that it does not have <strong>in</strong>tention or knowledge <strong>of</strong> death asan element. Yet generations <strong>of</strong> judges from Yas<strong>in</strong> to Lim Poh Lye have, atleast occasionally, balked at the idea that someone who acted without theknowledge that death would result should be convicted <strong>of</strong> murder, andwithout exception be punished with death. When they have been so28 There was <strong>in</strong>deed evidence <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong> a police statement that the accused<strong>in</strong>tended the wire to “go round her neck” (supra n 24, at 667, [41]), but the courtwas unwill<strong>in</strong>g to accept the truth <strong>of</strong> that assertion, given the existence <strong>of</strong> severalother statements which were rather less clear about what exactly was <strong>in</strong>tended. Itcould be argued that this factual f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g was wrong, and perhaps distorted by theconsequence <strong>of</strong> the alternative f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, but that was not the course <strong>of</strong> the judgment.

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 325m<strong>in</strong>ded, judges have seized upon an <strong>in</strong>herent ambiguity <strong>in</strong> s 300(c) –death occurs through a cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> events and s 300(c) does not tell usexactly how far along that cha<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> the accused must extend.So, another criterion has to be found, and the only <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ctive and ethicalone is none other than knowledge <strong>of</strong> lethality. 29 In short, s 300(c) can beconsistent and fair only if the judges work <strong>in</strong> an implicit calculation <strong>of</strong>knowledge <strong>of</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> death, but if that is done, the rationale fors 300(c) disappears, for the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g limbs <strong>of</strong> murder can now do thejob just as well. There have been attempts to make s 300(c) mean<strong>in</strong>gfuland more palatable – notably, it has been suggested that it embodies arequirement that a serious <strong>in</strong>jury must have been <strong>in</strong>tended. 30 That is betterthan just any <strong>in</strong>jury – for the more serious the <strong>in</strong>jury, the more likely it isthat the accused would have known that death might ensue. But this hasbeen repeatedly denied by Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh and almost every decision s<strong>in</strong>ce.More importantly, the requirement <strong>of</strong> a “serious <strong>in</strong>jury” itself conta<strong>in</strong>s an<strong>in</strong>herent ambiguity – how is seriousness to be measured? One only needsto look at the list which dist<strong>in</strong>guishes hurt from grievous hurt 31 – it wouldbe an open <strong>in</strong>vitation to argue <strong>in</strong>term<strong>in</strong>ably about how the list, for thepurpose <strong>of</strong> murder, is too narrow or too broad. Even more significantly,the only mean<strong>in</strong>gful and ethical way <strong>of</strong> decid<strong>in</strong>g when serious is seriousenough is, aga<strong>in</strong>, to work <strong>in</strong> a criterion <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong>death – a serious <strong>in</strong>jury is one which the accused knows is likely to causedeath. It could <strong>of</strong> course be an objective criterion – a serious <strong>in</strong>jury canbe that which is objectively likely to lead to death, but would render theproposed <strong>in</strong>tention to cause serious <strong>in</strong>jury the same as the exist<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>tention to cause any <strong>in</strong>jury.29 It is possible that some time <strong>in</strong> the future this k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> situation will give rise toproblems <strong>of</strong> constitutional due process under Art 9 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution <strong>of</strong> theRepublic <strong>of</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore because <strong>of</strong> a disproportionality between the crime (s 300(c)murder) and the punishment (mandatory death), and <strong>of</strong> constitutional <strong>in</strong>equalityunder Art 12 because s 300(c) murder is so qualitatively different from ss 300(a), (b)and (d), that it would be unjustifiably arbitrary to lump them all together for thepurpose <strong>of</strong> conviction and punishment. It is too early to predict if this will come topass, but foreign precedents are not hard to f<strong>in</strong>d: for example, the Supreme Court <strong>of</strong>Canada <strong>in</strong> R v Mart<strong>in</strong>eau [1990] 2 SCR 633 declared that pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> fundamentaljustice required a m<strong>in</strong>imum mens rea <strong>of</strong> subjective foresight <strong>of</strong> death for a murderconviction. I have elsewhere described a possibly nascent rule <strong>of</strong> customary<strong>in</strong>ternational law requir<strong>in</strong>g a “most serious” crime to justify the imposition <strong>of</strong> thedeath penalty: Michael Hor, “The Death Penalty <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore and International<strong>Law</strong>” (2004) 8 SYBIL 105.30 Notably by Ramraj, supra n 6.31 Section 320, Penal Code. For example, “fracture or dislocation <strong>of</strong> a bone” turns hurt<strong>in</strong>to grievous hurt, but there is no way <strong>of</strong> predict<strong>in</strong>g if an <strong>in</strong>tention to fracture a boneis an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause a serious enough <strong>in</strong>jury to attract s 300(c) without add<strong>in</strong>g acriterion <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> death.

326S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)21 I have no panacea for s 300(c). It is <strong>in</strong>curably <strong>in</strong>firm. 32 As long asit exists, it will rema<strong>in</strong> a gruesome nuisance. The situation is made worseby the mandatory death penalty that prevails for murder. A suitablediscretion might take care <strong>of</strong> the problems with a proportionate penalty,but the danger <strong>of</strong> unfair labell<strong>in</strong>g rema<strong>in</strong>s, and there are significantdifferences between cast<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g as an element <strong>of</strong> the crime andleav<strong>in</strong>g that consideration to the sentenc<strong>in</strong>g process. 33 Can we live withouts 300(c)? Lord Macaulay, the revered author <strong>of</strong> the draft Penal Code,certa<strong>in</strong>ly thought so. His orig<strong>in</strong>al draft would have def<strong>in</strong>ed murder asfollows: 34 Whoever does any act … with the <strong>in</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> thereby caus<strong>in</strong>g death, orwith the knowledge that he is thereby likely to cause the death <strong>of</strong> anyperson. [emphasis added]22 Clear, succ<strong>in</strong>ct and correct, as truly befits greatness.Lord Macaulay was anxious to reject constructive murder <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong>the <strong>in</strong>famous felony-murder rule. 35 He would have turned <strong>in</strong> his grave todiscover that his draft would be amended to give rise to possible birth <strong>of</strong>constructive murder <strong>of</strong> a specific k<strong>in</strong>d – for on its face s 300(c) may benoth<strong>in</strong>g else but a species <strong>of</strong> felony-murder. Thus the far lesser mens rea<strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause bodily <strong>in</strong>jury (<strong>of</strong> any k<strong>in</strong>d and severity) iselevated to the far greater mens rea <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause death orknowledge that death would be caused.23 The s 300(c) problem has been characterised as a tussle betweensubjective and objective conceptions <strong>of</strong> liability. 36 Yas<strong>in</strong> and, one supposes,all the cases <strong>in</strong> its tradition, have been accused <strong>of</strong> impos<strong>in</strong>g an alien32 From the standpo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> technical statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation, the court has <strong>of</strong>ten feltimpelled to search for a mean<strong>in</strong>g to s 300(c) which is different from the other limbs –the Legislature is not to be presumed to have legislated <strong>in</strong> va<strong>in</strong>, and s 300(c) cannotbe merely otiose. The irony is that, hav<strong>in</strong>g discovered that different mean<strong>in</strong>g tos 300(c), the court has now for all <strong>in</strong>tents and purposes rendered all the other limbsotiose. One struggles to f<strong>in</strong>d a reported case <strong>in</strong> the past thirty years <strong>in</strong> which a courthas based its decision on any <strong>of</strong> the other limbs. The last was probably Tan ChengEng William v PP [1969–1971] SLR 115 <strong>in</strong> which the Prosecution failed to make outa s 300(d) murder.33 For example, evidential and procedural safeguards which apply to the convictionprocess do not clearly apply to the sentenc<strong>in</strong>g decision.34 A Penal Code Prepared by the Indian <strong>Law</strong> Commissioners (The <strong>Law</strong>book Exchange,Ltd, Repr<strong>in</strong>t 2002) at p 38.35 Under this common law doctr<strong>in</strong>e, a person who kills <strong>in</strong> the course <strong>of</strong> thecommission <strong>of</strong> a felony is guilty <strong>of</strong> murder even if he or she does not have the mensrea for murder – essentially the mens rea <strong>of</strong> murder is constructed from pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> themens rea <strong>of</strong> the felony concerned.36 Notably Sornarajah, supra n 6.

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 327subjectivist idea <strong>of</strong> liability on a more objectivist conception found <strong>in</strong>s 300(c). Be that as it may, few would argue that one ought to start withthe ethical presumption that the crim<strong>in</strong>al law should be as subjective aspractical circumstances will allow. Rational justification <strong>of</strong> the existence<strong>of</strong> s 300(c) is rare <strong>in</strong>deed and those which exist are far from conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g.Witness the classic attempt <strong>in</strong> Virsa S<strong>in</strong>gh: 37No one has a licence to run around <strong>in</strong>flict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>juries that are sufficientto cause death <strong>in</strong> the ord<strong>in</strong>ary course <strong>of</strong> nature and claim that they arenot guilty <strong>of</strong> murder. If they <strong>in</strong>flict <strong>in</strong>juries <strong>of</strong> that k<strong>in</strong>d, they must facethe consequences …24 Indeed no one has a licence to <strong>in</strong>flict <strong>in</strong>juries <strong>of</strong> any k<strong>in</strong>d withoutlawful justification or excuse. Wrongdoers must <strong>in</strong>deed face theconsequences, but why must the consequence be a murder conviction,and <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore, a mandatory death penalty? Will noth<strong>in</strong>g else suffice?Macaulay was brilliantly contemptuous <strong>in</strong> his denunciation <strong>of</strong> felonymurder.He called it “senseless cruelty”, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that: 38To punish as a murderer every man who, while committ<strong>in</strong>g a he<strong>in</strong>ous<strong>of</strong>fence, causes death by pure misadventure, is a course which evidentlyadds noth<strong>in</strong>g to the security <strong>of</strong> human life.25 It was, if we were to follow the sentiments <strong>of</strong> Lord Macaulay,cruelty to punish someone with only an <strong>in</strong>tention to <strong>in</strong>jure, with thesupreme penalty reserved for murder, and if it is desired to deter all actswhich <strong>in</strong>tentionally <strong>in</strong>jure, there are other lesser <strong>of</strong>fences which do thework. If it is thought that the punishment for these <strong>of</strong>fences are too light,the solution is to <strong>in</strong>crease the punishment, not to punish those who kill<strong>in</strong>advertently with murder. There is no doubt that had Macaulay beenshown s 300(c), this is precisely what he would have thought <strong>of</strong> it.26 Why s 300(c) rema<strong>in</strong>s is an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g question. Leav<strong>in</strong>g aside thevagaries <strong>of</strong> Parliamentary attention, if it were <strong>in</strong>deed proposed thats 300(c) be repealed, what would the potential objectors say?Extrapolat<strong>in</strong>g from exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>ficial discourse on mens rea, one cansurmise that the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal objection will be this – to require theprosecution to prove either an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause death or knowledgethere<strong>of</strong> will be unduly burdensome. All accused persons will then claimthat they did not <strong>in</strong>tend or know. The situation will be unmanageable.Leave s 300(c) there. If there are <strong>in</strong>deed deserv<strong>in</strong>g cases, do not worry,37 Supra n 9, at 467.38 A Penal Code Prepared by the Indian <strong>Law</strong> Commissioners, supra n 34, at p 111.

328S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)prosecutorial discretion will be exercised <strong>in</strong> their favour. Besides, thecourts have the Yas<strong>in</strong> avenue <strong>of</strong> acquitt<strong>in</strong>g the accused. It would betedious to respond to these objections <strong>in</strong> detail, all <strong>of</strong> which smack <strong>of</strong> anextreme form <strong>of</strong> managerialism with its dubious assumption thatbureaucratic efficiency is the primary consideration <strong>in</strong> such matters.There are a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences for which <strong>in</strong>tention or knowledge isnecessary 39– it has not been the experience that they have created anunmanageable situation. The prosecution rout<strong>in</strong>ely proves such th<strong>in</strong>gs,and if one were to exam<strong>in</strong>e the facts <strong>of</strong> s 300(c) convictions, a great manywould have clearly satisfied a full mens rea requirement. Aga<strong>in</strong>, look<strong>in</strong>g atVirsa S<strong>in</strong>gh – the accused plunged a spear so forcefully <strong>in</strong>to the belly <strong>of</strong>the victim that his <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>es fell out – how could it even be suggested thatdeath was not contemplated?27 Section 300(c) was not necessary to convict the accused <strong>of</strong>murder. As we shall see the Legislature does sometimes tamper with themens rea <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences which are perceived to be particularly alarm<strong>in</strong>g and“on the rise”, but murder is hardly a rampant crime <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore. 40 It isnot satisfactory to leave it to prosecutorial discretion to dist<strong>in</strong>guishbetween advertent and <strong>in</strong>advertent caus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> death. There is noguarantee that, as long as s 300(c) rema<strong>in</strong>s, those whom the prosecutorsbelieve not to have full mens rea will not be prosecuted. If the prosecutorsbelieve so firmly that the accused had full mens rea, let that be proven <strong>in</strong>court where m<strong>in</strong>imum due process standards apply. Where full mens reacannot be proven <strong>in</strong> court, the accused should not be guilty <strong>of</strong> murder.Even if we assume that prosecutors are unfail<strong>in</strong>gly scrupulous <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>gs 300(c) only where they believe full mens rea to exist, their belief shouldnot be elevated to the status <strong>of</strong> proven facts – prosecutors are human andcan be wrong. Similarly, rely<strong>in</strong>g on the courts to occasionally pull a Yas<strong>in</strong>out <strong>of</strong> the hat is unsatisfactory. There is no guarantee that all courtswould be so m<strong>in</strong>ded, even if they are <strong>of</strong> the view that full mens rea has notbeen proven. Given the near pariah status <strong>of</strong> Yas<strong>in</strong>, it is more thanconceivable that at least some judges will take s 300(c) quite literally andactually th<strong>in</strong>k that <strong>in</strong>tention or knowledge <strong>of</strong> death is irrelevant. Oneonly hopes that these k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> objections are not brought to bear on the39 For example, the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal “property” <strong>of</strong>fences typically require “dishonesty” whichis clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> s 24 <strong>of</strong> the Penal Code to be an <strong>in</strong>tention to cause wrongful lossor ga<strong>in</strong>.40 The murder rate <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore compares favourably with that <strong>of</strong> Japan, which islegendary: Yeo Soek Lee, “Crime Trends <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore” (accessed 29 March 2005).

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 329issue when the day comes for those <strong>in</strong> power to consider the repeal <strong>of</strong>s 300(c). 41II.To know or ought to know – that is the question28 While the court cannot be held responsible for the <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong>s 300(c) <strong>in</strong> the Penal Code, they have, <strong>in</strong> an astound<strong>in</strong>g series <strong>of</strong> cases <strong>in</strong>drugs and immigration prosecutions, sought to confuse the mens rea <strong>of</strong>knowledge and <strong>of</strong> negligence. To know someth<strong>in</strong>g is to be actually aware<strong>of</strong> its existence – this is normally accepted to be the higher or moreblameworthy form <strong>of</strong> mens rea. Negligence is the situation where there isno actual knowledge, but the context or circumstances are such that areasonable person ought to have known, or ought to have checked – thisis a lower or less blameworthy form <strong>of</strong> mens rea, a state <strong>of</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d which isoccasionally made crim<strong>in</strong>al. It is important to appreciate the differencebetween the two. Courts rem<strong>in</strong>d us that there is <strong>of</strong>ten little chance <strong>of</strong>direct evidence <strong>of</strong> knowledge 42 – so <strong>in</strong> practice knowledge is <strong>in</strong>ferred fromcircumstantial evidence. A large part <strong>of</strong> the assessment <strong>of</strong> circumstantialevidence <strong>in</strong>volves the question <strong>of</strong> whether a reasonable person <strong>in</strong> theposition <strong>of</strong> the accused would have known. 43 One might even say that allelse be<strong>in</strong>g equal, the same evidence which goes to show negligence willalso go to show knowledge. However, where knowledge is the prescribedmens rea, the fact that a reasonable person ought to have known is only41 There are formidable obstacles <strong>in</strong> the way <strong>of</strong> any such notion. Crim<strong>in</strong>al lawlegislation has been almost exclusively “bureaucracy driven” lead<strong>in</strong>g to changeswhich maximise the efficiency <strong>of</strong> the bureaucracy <strong>in</strong> curb<strong>in</strong>g particular crim<strong>in</strong>alactivity. There is also a prevail<strong>in</strong>g belief that the <strong>in</strong>herited English common law hadsomehow struck the balance too much <strong>in</strong> favour <strong>of</strong> the rights <strong>of</strong> the accused, asopposed to the <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the prosecution (and therefore <strong>of</strong> the “public” beh<strong>in</strong>d it)– then Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister Lee Kuan Yew has said, <strong>in</strong> his speech at the Open<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> theS<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> on 31 August 1990, (accessed 30 March 2005) (also published as Lee Kuan Yew,“Address by the Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew” (1990) 2 SAcLJ 155 at 155):In English doctr<strong>in</strong>e, the rights <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual must be the paramountconsideration. We shook ourselves free from the conf<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> English normswhich did not accord with customs and values <strong>of</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore society. In crim<strong>in</strong>allaw legislation, our priority is the security and well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> law-abid<strong>in</strong>g citizensrather than the rights <strong>of</strong> the crim<strong>in</strong>al to be protected from <strong>in</strong>crim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>gevidence.42 This observation needs to be significantly qualified <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore where there is not<strong>in</strong>frequently the existence <strong>of</strong> confessions made by the accused to the police <strong>in</strong> thecourse <strong>of</strong> police <strong>in</strong>terrogation – see, for example, the extensive use <strong>of</strong> suchstatements to prove knowledge <strong>in</strong> the recent drugs case <strong>of</strong> PP v Nguyen Tuong Van[2004] 2 SLR 328.43 For the reason that the fact that a reasonable person would have known bears on thecredibility <strong>of</strong> an accused person who has testified that he or she did not know.

330S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>quiry – it is probative, not dispositive, <strong>of</strong> knowledge. It isquite possible that the facts <strong>of</strong> a particular case will show that the accuseddid not actually know, although a reasonable person ought to haveknown. 4429 Where the Legislature has clearly prescribed a particular mens reafor an <strong>of</strong>fence, the courts have no legitimate creative function to fashionother forms <strong>of</strong> mens rea which they feel will do better. Yet <strong>in</strong> a series <strong>of</strong>drugs and immigration cases, the courts have done just that. 45 The Misuse<strong>of</strong> Drugs Act (“MDA”) makes it an <strong>of</strong>fence to traffic <strong>in</strong> a controlled drug,or to possess a controlled drug for the purpose <strong>of</strong> traffick<strong>in</strong>g. 46 Where thedrug exceeds a certa<strong>in</strong> stipulated amount, the MDA famously imposes amandatory sentence <strong>of</strong> death. 47The question is whether, to be guilty <strong>of</strong>the <strong>of</strong>fence, the accused must know that the th<strong>in</strong>g trafficked or possessedis a controlled drug. The words “traffic” and “possess” and its cognateexpressions are ambiguous. The precise mens rea <strong>of</strong> (especially) theelement <strong>of</strong> possession has been historically problematic both locally andelsewhere. 48 Even so, one might have thought that given the existence <strong>of</strong> amandatory death penalty, the uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty ought to be resolved <strong>in</strong> favour<strong>of</strong> the accused and a mens rea <strong>of</strong> knowledge required by implication.Indeed, the MDA conta<strong>in</strong>s a presumption which ought to have settled thematter:44 There could be any number <strong>of</strong> reasons. For example, the accused may possess certa<strong>in</strong>personal characteristics which are not taken <strong>in</strong>to account for the test <strong>of</strong> thereasonable person, or the accused was simply be<strong>in</strong>g less prudent than a reasonableperson would have been.45 Many <strong>of</strong> the ideas <strong>in</strong> this section were developed from those first expressed <strong>in</strong> twoarticles: Michael Hor, “Misuse <strong>of</strong> Drugs and Aberrations <strong>in</strong> the Crim<strong>in</strong>al <strong>Law</strong>”(2001) 13 SAcLJ 54; Michael Hor, “Illegal Immigration: Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple and Pragmatism <strong>in</strong>the Crim<strong>in</strong>al <strong>Law</strong>” (2002) 14 SAcLJ 18.46 Section 5, Misuse <strong>of</strong> Drugs Act (Cap 185, 2001 Rev Ed).47 MDA, id, Second Schedule.48 An important precedent <strong>in</strong> the pro-knowledge camp is Toh Ah Loh v R [1949] MLJ54 (“Toh Ah Loh”), which declared, at 54–55:Possession, <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>crim<strong>in</strong>ate a person, must have the follow<strong>in</strong>gcharacteristics. The possessor must know the nature <strong>of</strong> the th<strong>in</strong>g possessed,must have <strong>in</strong> him a power <strong>of</strong> disposal over the th<strong>in</strong>g, and lastly must beconscious <strong>of</strong> his possession <strong>of</strong> the th<strong>in</strong>g. If these factors are absent, hispossession can raise no presumption <strong>of</strong> mens rea, without which (except bystatute) possession cannot be crim<strong>in</strong>al.Though widely respected, Toh Ah Loh did not command absolute allegiance: see, forexample, Leow Nghee Lim v R [1956] MLJ 28, and the early but able discussion <strong>of</strong>Bron McKillop, “Strict Liability Offences <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore and Malaysia” (1967) 9 MalLR 118 at 137–144, who concluded rather gloomily, at 144:It seems almost that for every case <strong>in</strong> which the courts here have opted for mensrea another case on the same or a similar <strong>of</strong>fence can be found <strong>in</strong> which liabilityhas been held to be strict, and vice-versa.

18 SAcLJ 314 <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Mens</strong> <strong>Rea</strong> <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore 331Any person who is proved or presumed to have had a controlled drug <strong>in</strong>his possession shall, until the contrary is proved, be presumed to haveknown the nature <strong>of</strong> that drug. [emphasis added]30 Knowledge <strong>of</strong> the nature <strong>of</strong> the drug is the mens rea theLegislature had <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d – otherwise it would be po<strong>in</strong>tless to presume itsexistence. But the burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> is shifted, where the presumption istriggered, to the accused to prove that there was no such knowledge. Itmust follow that if the accused rebuts the presumption by prov<strong>in</strong>g that heor she did not know the nature <strong>of</strong> the drug, the prosecution must fail. In1979 the unfortunate case <strong>of</strong> Tan Ah Tee v PP was decided. 49 It was a casewhich was dest<strong>in</strong>ed to plague our drugs law s<strong>in</strong>ce. Instead <strong>of</strong> constru<strong>in</strong>gthe MDA on its own terms, the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal <strong>in</strong>explicably adopted the<strong>in</strong>terpretation by Lord Pearce <strong>in</strong> a House <strong>of</strong> Lords decision 50<strong>of</strong> theEnglish drugs legislation, a law which did not conta<strong>in</strong> the crucialpresumption <strong>of</strong> knowledge or the possibility <strong>of</strong> a death penalty.Lord Pearce was <strong>of</strong> the view that the <strong>of</strong>fence was established <strong>in</strong> twosituations where the accused did not actually know that what was <strong>in</strong>possession was drugs: 51I th<strong>in</strong>k that the term “possession” is satisfied by a knowledge only <strong>of</strong> theexistence <strong>of</strong> the th<strong>in</strong>g itself and not its qualities, and that ignorance ormistake as to its qualities is not an excuse. This would comply with thegeneral understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the word “possess.” Though I reasonably believethe tablets which I possess to be aspir<strong>in</strong>, yet if they turn out to be hero<strong>in</strong> Iam <strong>in</strong> possession <strong>of</strong> hero<strong>in</strong> tablets. …… Thus the prima facie assumption [<strong>of</strong> mens rea, upon pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>possession <strong>of</strong> a conta<strong>in</strong>er with drugs <strong>in</strong> it] is discharged if he proves (orraises a real doubt <strong>in</strong> the matter) either (a) that he was a servant orbailee who had no right to open it and no reason to suspect that itscontents were illicit or were drugs or (b) that although he was the ownerhe had no knowledge <strong>of</strong> (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a genu<strong>in</strong>e mistake as to) its actualcontents or <strong>of</strong> their illicit nature and that he received them <strong>in</strong>nocentlyand also that he had had no reasonable opportunity s<strong>in</strong>ce receiv<strong>in</strong>g thepackage <strong>of</strong> acqua<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g himself with its actual contents. For a man takesover a package or suitcase at risk as to its contents be<strong>in</strong>g unlawful if hedoes not immediately exam<strong>in</strong>e it (if he is entitled to do so).[emphasis added]31 It is obvious that whatever the validity <strong>of</strong> these pronouncementsunder English law, they cannot apply to the MDA. The first proposition is49 [1978–1979] SLR 211 (“Tan Ah Tee”).50 Warner v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1969] 2 AC 256 (“Warner”).51 Id, at 305–306.

332S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Journal (2006)particularly serious: it is strict liability <strong>in</strong> the strictest sense – it is not evennegligence for reasonable belief does not exonerate. If the Court <strong>of</strong>Appeal had been advertent <strong>of</strong> the presumption <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>in</strong> the MDA,accused persons do <strong>in</strong>deed have a good defence if they can prove thatthey did not know, for <strong>in</strong>stance, that the tablets were hero<strong>in</strong>, whether ornot the belief was reasonable. The second proposition, the position forconta<strong>in</strong>ers, builds on the first and, essentially, fixes the accused withknowledge <strong>of</strong> the “th<strong>in</strong>g itself” if he or she ought to have known orchecked the contents <strong>of</strong> the conta<strong>in</strong>er <strong>in</strong> possession. It is a negligencestandard upon strict liability. Aga<strong>in</strong>, if the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal had beenadvertent <strong>of</strong> the presumption <strong>in</strong> the MDA, none <strong>of</strong> this could be the case<strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore – whether the drug is <strong>in</strong> the open or <strong>in</strong> a conta<strong>in</strong>er, theaccused has a good defence if it is proven that there was no knowledgethat he or she had controlled drugs <strong>in</strong> possession.32 There is much that is wrong about rely<strong>in</strong>g on Lord Pearce to<strong>in</strong>terpret the MDA, but if reliance there must be, it ought to have been onanother portion <strong>of</strong> the judgment, which the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal, surpris<strong>in</strong>glyalso quotes: 52… Parliament may have <strong>in</strong>tended what was described as a “halfwayhouse” … By this method the mere physical possession <strong>of</strong> drugs wouldbe enough to throw on a defendant the onus <strong>of</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g his<strong>in</strong>nocence, and unless he did so (on a balance <strong>of</strong> probabilities) he wouldbe convicted. The Explosive Substances Act, 1883, produces this fair andsensible result but it does so by express words … [emphasis added]33 In other words, had there been a presumption such as the onewhich exists <strong>in</strong> the MDA, Lord Pearce himself would have given effect toit, and that would have been the fair and sensible th<strong>in</strong>g to do. But he felthe could not legislate for Parliament. There can be no doubt that theCourt <strong>of</strong> Appeal, <strong>in</strong> adopt<strong>in</strong>g Lord Pearce’s conclusions (and not even hisreason<strong>in</strong>g), was act<strong>in</strong>g per <strong>in</strong>curiam, because it had been <strong>in</strong>advertent <strong>of</strong> adirectly applicable statutory provision – the express rebuttablepresumption <strong>of</strong> knowledge under the MDA.34 One would have thought that such a clear error would have beencorrected at the first opportunity but that was not to happen. A swarm <strong>of</strong>decisions s<strong>in</strong>ce 1979 have quoted Tan Ah Tee with approval. 53 Eventually,<strong>of</strong> course, the hitherto unnoticed presumption <strong>of</strong> knowledge did catch52 Id, at 30<strong>2.</strong>53 Notably <strong>in</strong> the recent case <strong>of</strong> Shan Kai Weng v PP , <strong>in</strong>fra n 63.