free law journal - volume 3, number 1 (18 january 2007)

free law journal - volume 3, number 1 (18 january 2007)

free law journal - volume 3, number 1 (18 january 2007)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

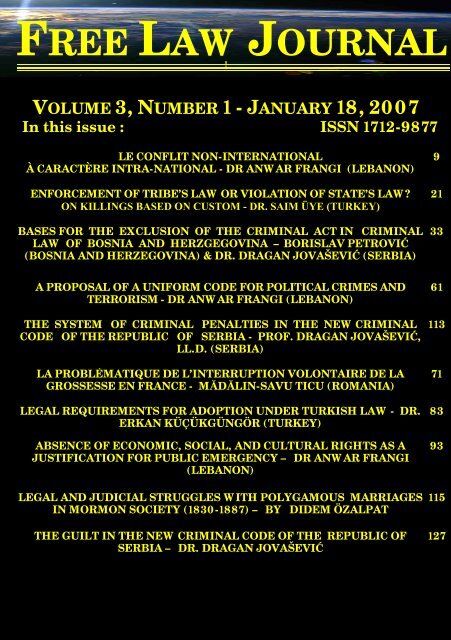

FREE LAW JOURNAL!VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 - JANUARY <strong>18</strong>, <strong>2007</strong>In this issue : ISSN 1712-9877LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL - DR ANWAR FRANGI (LEBANON)ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATION OF STATE’S LAW?ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM - DR. SAIM ÜYE (TURKEY)BASES FOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA – BORISLAV PETROVIĆ(BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA) & DR. DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ (SERBIA)92133A PROPOSAL OF A UNIFORM CODE FOR POLITICAL CRIMES ANDTERRORISM - DR ANWAR FRANGI (LEBANON)THE SYSTEM OF CRIMINAL PENALTIES IN THE NEW CRIMINALCODE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA - PROF. DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ,LL.D. (SERBIA)LA PROBLÉMATIQUE DE L’INTERRUPTION VOLONTAIRE DE LAGROSSESSE EN FRANCE - MĂDĂLIN-SAVU TICU (ROMANIA)LEGAL REQUIREMENTS FOR ADOPTION UNDER TURKISH LAW - DR.ERKAN KÜÇÜKGÜNGÖR (TURKEY)ABSENCE OF ECONOMIC, SOCIAL, AND CULTURAL RIGHTS AS AJUSTIFICATION FOR PUBLIC EMERGENCY – DR ANWAR FRANGI(LEBANON)LEGAL AND JUDICIAL STRUGGLES WITH POLYGAMOUS MARRIAGESIN MORMON SOCIETY (<strong>18</strong>30-<strong>18</strong>87) – BY DIDEM ÖZALPATTHE GUILT IN THE NEW CRIMINAL CODE OF THE REPUBLIC OFSERBIA – DR. DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ611137<strong>18</strong>393115127

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)The Free Law Journal results of a merger with theEastern European Law Journals. It builds upon thisprevious success and aims at providing the <strong>free</strong>dom ofpublishing juridical research from everywhere and onall subjects of <strong>law</strong>. Its goal is to promote respect of therule of <strong>law</strong> and the fair application of justice by sharingjuridical research in its pages.Academics, post-graduate students and practitioners of<strong>law</strong> are welcome to submit in the academic section theirarticles, notes, book reviews or comments on any legalsubject, while undergraduate students are welcome topublish in our student section. The list of fields of <strong>law</strong>addressed in these pages is ever-expanding and nonrestrictive,as needs and interests arise. If a field is notlisted, the author simply needs to propose the articleand the field believed of <strong>law</strong> applicable; we will insure tocreate and list it.We accept articles in English, French, Bosnian,Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Finnish, German, Greek,Hungarian, Icelandic, Inuktitut, Italian, Latin, Polish,Portuguese (both Brazilian and European), Romanian,Russian, Serb (both Latin and Cyrillic), Slovenian,Spanish and Turkish.Articles not in English are provided with a synopsis toexplain their content. Articles of exceptional quality, orrequested to be, can be translated into English and/orFrench. All of this is the measure of <strong>free</strong>dom we provide.The material submitted for publication remainscopyrighted to the author. If the author has interest inpublishing elsewhere after having published in ourpages, no permission to do so will be necessary. Theauthor remains in full control of his or her writings.Articles of superior value will be considered forincorporation in collective works for publishing.2FREE WORLD PUBLISHING Inc. @http://www.

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)We always accept submissions. To submit, please readthe submission guidelines or ask us any question at:FLJ@FWPublishing.net .List of subject addressed(as it currently stands - modified as need arise)Administrative LawAdmiralty <strong>law</strong>Antitrust <strong>law</strong>Alternative disputeresolutionAnti-TerrorismBankruptcyBusiness LawCanon LawCivil LawCommon LawComparative LawConstitutional LawContract Law(Consuetudinary <strong>law</strong>)ObligationsQuasi-contractCorporations <strong>law</strong>Criminal LawOrganised CrimeCriminal ProcedureCyber Crime LawPenal <strong>law</strong>Cyber <strong>law</strong>Election <strong>law</strong>Environmental <strong>law</strong>European LawEvidence LawFamily <strong>law</strong>History of LawHuman Rights LawImmigration LawIntellectual Property LawInternational trade <strong>law</strong>PatentTrademark LawInternational HumanitarianRights LawLaws of Armed ConflictsLaws of warWar Crimes Law (Belgium)International Law (Public)Diplomatic RelationsJus GentiumTreaties LawLabor <strong>law</strong>Law and economicsLaw and literatureMedical LawPublic Health LawPublic LawMalpracticeMental health <strong>law</strong>Military <strong>law</strong>National Legal Systems -(Laws of any national legalsystem that is not of aprecise category)Nationality and naturalisationLawsNatural <strong>law</strong>Philosophy of LawPrivate International LawPrivate <strong>law</strong>Procedural <strong>law</strong>Property <strong>law</strong> (Public)International Law (SeeInternational Law (Public))Refugee LawReligious <strong>law</strong>Islamic Law (Sharia)Qur'anShariaJewish <strong>law</strong> (Halakha)Hebrew <strong>law</strong> (Mishpat Ivri)TalmudTaqlidChristian (other than CanonLaw)Twelve TablesRoman LawSacred textState of Emergencies LawsSpace <strong>law</strong>Tax <strong>law</strong>Technology <strong>law</strong>Torts LawQuasi-delictTrusts and estates LawLiensWater <strong>law</strong>ZoningFree World Publishing is a partner of the Free EuropeanCollegium, provider of web-based, e-learning education inmatters related to the European Union.3

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)All material published are available for <strong>free</strong> athttp://www.FWPublishing.net and can be used <strong>free</strong>lyfor research purposes, as long as the authors’ sourcesare acknowledged in keeping with national standardsand <strong>law</strong>s regarding copyrights.All mail correspondence can be made with the editorialboard at 82-146 Stewart Street, Ottawa, Ontario, K1N6J7 Canada, while electronic correspondence can bemade through FLJ@FWPublishing.net .The views and opinions expressed in these pages aresolely those of the authors and not necessarily those ofthe editors, Free World Publishing Inc. or that of theFree European Collegium Inc.Cited as (<strong>2007</strong>) 3(1) Free L. J.ISSN 1712-98774

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)FREE LAW JOURNAL SUBMISSION GUIDELINESImportant. The following is not meant to discouragefrom submitting; only to ensure quality. If your articleconforms to your own national standard of writings, weaccept all and any format as long as arguments arejustified by footnotes or endnotes. Never hesitate tosubmit an article : if there is a need for improvement,we will inform you and we will always remain open forre-submissions.1. Academics, Post-Graduate Students and Practitionersof <strong>law</strong> are all welcomed to publish their book reviews,comments, notes and articles.2. All legal subjects are considered for publication,regardless of the legal tradition, national orinternational field of expertise. The only limit to theextend of our publishing would be content that is illegalin national legislation (i.e. enticement to hatred) oragainst international norms (i.e. promoting genocide).3. Articles are welcomed in English, French, Bosnian,Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Finnish, German, Greek,Hungarian, Icelandic, Innuktikut, Italian, Latin, Polish,Portuguese (both Brazilian and European), Romanian,Russian, Serb (both Latin and Cyrillic), Slovenian,Spanish and Turkish. Note that our staff is limited andtherefore we use "Word RecognitionProcessors" to communicate in some languages.Nonetheless, this does not prevent understandingarticles submitted in these language and we are notinterested in measuring every word of your article:simply in publishing your writings. Therefore, we willreview the general content, but leave with you theprecise sense and meaning that you want to convey inyour own language. If translation is desired by theauthor, we then submit it for translation to a translator.5

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)4. Their is no defined system of reference (footnotes orendnotes) demanded. As long as you justify yourargument through references (author and work), weaccept all writings respecting your own nationalstandards. Exceptions: For Canadians, the CanadianLegal Guide to Citation is recommended but notmandatory. For Americans, referencing is expected tobe in accordance with Harvard University's TheBluebook, A Uniform System of Citation. Any breach ofcopyrights is the sole responsibility of the author.5. The author retains the copyrights to his or herwritings. As articles are unpaid for, ownership remainswithin your hands. We act as publishers and caretaker.Nothing prevents you from publishing elsewhere. Youmay even decide to have the article taken off this site ifanother publisher desires to buy the rights to yourarticle.6. We reserve ourselves the right to edit the content orlength of the article, if at all necessary.7. We do not discriminate in any way. Our aim is tobring under one roof perspectives from everywhere andeveryone. Never hesitate to submit.8. If you desire information or desire to submit, do nothesitate to contact us at : FLJ@FWPublishing.net.6

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)EDITORIALWelcome to the last <strong>number</strong> of the second <strong>volume</strong> of the Free LawJournal, a print and electronic <strong>journal</strong> aiming at promotingrespect of the rule of <strong>law</strong> and the fair application of justiceeverywhere through the sharing of juridical research.The Free Law Journal’s first issue was a definitive success interms of scope and reach, registering a very high <strong>volume</strong> ofconsultation on the web and orders of paper copies. This signals adefinitive interest in getting to know the legal research producedeverywhere and to share this knowledge.As such, this permits us to reach our first and foremost objectiveto promote the rule of <strong>law</strong>. Knowledge is definitely part of theapplication of this objective and we see a clear desire from peopleall over the world to gain access to this knowledge in order tofoster the fair application of justice for all.Therefore, welcome and we hope that our contributions to legalresearch and knowledge will expand through your writtencontributions.Sincerely,Louis-Philippe F. RouillardEditor-in-Chief, Free World Publishing Inc.7

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)8

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONALPAR LE DR ANWAR FRANGI [ 1 ]1. Introduction: Le conflit non-international se décompose,selon le droit humanitaire international, en deux sens. (1) Le sensprévu par l’article 3 Commun aux 4 Conventions de Genève de1949, et (2) celui prévu par l’article premier du Protocol II de1977. Le premier sens entraîne des situations où une factionarmée s’oppose à une autre faction armée, et où le gouvernementn’est pas nécessairement une Partie au conflit. Le second senscouvre des situations où le gouvernement s’oppose à des forcesarmées nationales dissidentes.Je dis que le conflit non-international a un troisième sens, àsavoir le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national.2. Concept: Le Conflit non-international à caractère intranationalest un conflit généré par un acte international par soinon-conflictuel ou par un conflit international. Il couvre lesmêmes situations que couvre le conflit non-international ‘positif’,dans ses deux sens, c’est-à-dire des situations où une factionarmée s’oppose à une autre faction armée, ou des situations où legouvernement s’oppose à des forces armées nationales1 LL.M. 1995, Faculté de Droit de l’Université Harvard (Massachusetts, USA);LL.M. 1992, Faculté de Droit de l’Université Américaine (Washington, D.C.);Doctorat en droit 1986, Faculté de Droit de l’Université de Poitiers (France);D.E.A. 1983, Faculté de Droit de l’Université de Poitiers (France); Licence dedroit 1982, Faculté de Droit de l’Université libanaise (Liban). Dr Frangi estprofesseur assistant et chercheur à l’Université Saint-Esprit de Kaslik (Liban),et professeur de droit international et de philosophie du droit à la Faculté dedroit de l’Université La Sagesse (Liban).9DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)dissidentes; seulement son caractère intra-national entraîne desconséquences juridiques sérieuses que ne peut emporter lecaractère national du conflit non-international ‘positif’. Nous yreviendrons au paragraphe (4) infra.Le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national diffère duConflit non-international ‘positif’ par le fait que l’origine de cedernier est nationale, alors que celle du Conflit non-internationalà caractère intra-national est internationale. J’entends par‘origine’ la ‘dérivation’ du conflit non-international à partir d’unconflit ou d’un acte international. Le concept ‘origine’ évoquedonc celui de ‘mouvement’ où le conflit ou l’acte passe d’unniveau international à un niveau non-international en parcourantune série d’étapes intermédiaires allant de la génération desréfugiés, des tensions, des troubles à celle des conflits noninternationaux.Lorsqu’il est le résultat d’un conflit international,le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national prend‘l’aspect non-international’ du Conflit international intranationalisé(v° « The Intra-Nationalized International Conflict »,Free L.J. 2005 1(2), p. 43). Ainsi le Conflit non-international àcaractère intra-national englobe t-il le sens d’un conflit noninternationalengendré par un conflit international et le sens d’unconflit non-international engendré par un acte international parsoi non-conflictuel. Voici des exemples du conflit noninternationalpouvant être généré par un acte initial internationalpar soi non-conflictuel. (a) Le processus de démocratisation quise matérialise dans des constitutions nationales que les grandespuissances aident les pays en voie de démocratisation à rédiger, etqui dégénère dans la plupart des cas en un conflit noninternational,dès lors que les principes par soi démocratiques surlesquels se repose la nouvelle constitution nationale ne s’accordepas harmonieusement avec les coutumes nationales, ce qui exigede la part des autochtones un effort d’adaptation et encoredéfaillant. (b) Les Résolutions du Conseil de sécurité des Nationsunies, telle que la Résolution 1701, qui peuvent dégénérer en unconflit non-international, dès lors que leur compréhensioncommande plusieurs interprétations. (c) L’acte discriminatoire: le10DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)conflit non-international israélo-palestinien en Palestine dans lesannées 40 est l’aboutissement de l’acte discriminatoire dansplusieurs pays européens envers les juifs qui a dégénéré en fluxmigratoires des juifs d’Europe orientale vers la Palestine. (d)L’acte de paix, tel que la paix séparée entre l’Egypte et l’Etatd’Israël qui a relancé les conflits non-internationaux au Libanaprès un court répit en 1977.Aussi le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-nationaldiffère-t-il des concepts tels que « la guerre pour les autres », « laguerre par les autres », « la guerre des autres » ou « la guerre parprocuration ». « La guerre pour les autres » et « la guerre par lesautres » ne représentent qu’une seule et même chose. « La guerrepour les autres » implique un conflit armé, international ou non,mais commandé ou dirigé par des Etats qui ne sont pas impliquésdirectement dans le conflit. Dans la plupart des cas les Partiesimpliquées directement dans le conflit sont des agents des Etatsétrangers pour qui la guerre se fait, et leur allégeance à leur Etatest mise en doute. Car la décision des options de guerre ou depaix n’est pas prise par eux, mais par ceux pour qui la guerre estfaite. Aussi, « la guerre par les autres » signifie que les Partiesindirectement impliquées dans la guerre sont à l’origine du conflitqui se déroule. Mais différemment de « la guerre pour lesautres », « la guerre par les autres » peut avoir le sens del’internationalisation, pas l’intra-nationalisation, dès lors que,étant donné un conflit non-international à l’origine, des Etatsétrangers au conflit aident matériellement les Parties impliquéesdans le conflit non-international l’exacerbant ainsi et y vidant leurpropre conflit. Le cas où les Parties au conflit apparemment noninternationalseraient des agents des Etats étrangers, le conflitserait donc qualifié plutôt de conflit international que de conflit àcaractère intra-national. Ainsi « la guerre par les autres », le casoù elle aurait la forme d’un conflit non-international, peut-elle serapprocher seulement de l’internationalisation, pas de l’intranationalisation.L’expression « la guerre des autres » s’aligne surle sens général des deux autres expressions, « la guerre pour lesautres » et « la guerre par les autres ». Elle peut être ou bien faite11DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)« par les autres » sur le territoire de l’un de ces derniers, ou bienfaite en sorte que le conflit soit fait « pour les autres ». Mais,différemment de « la guerre pour les autres » et de « la guerre parles autres », « la guerre des autres » peut être faite par les Partiesau conflit elles-mêmes sur le territoire d’un tiers. « La guerre parprocuration » peut être similaire à « la guerre pour les autres »,les Parties impliquées directement dans un conflit armé,international ou non, étant Parties à ce conflit plutôt pour lecompte des autres que pour leur propre compte. « La guerre parprocuration » peut aussi être similaire à « la guerre par lesautres », dès lors que les Parties impliquées dans un conflit le fontpar soumission à la volonté des Etats étrangers, et quel’implication de ces derniers dans le conflit n’est pas faite après ledéclenchement des hostilités, le cas où le conflit serait à caractèrenon-international, sinon le conflit serait qualifié de conflit noninternationalinternationalisé comme nous avons déjà mentionné.Le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national sedistingue de l’ensemble de ces genres de guerre par le fait queselon ces derniers une intention spéciale internationale estrequise à l’origine du conflit, international ou non, alors que selonle Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national il est requisdes Parties au conflit ou à l’acte international une conscience desconséquences naturelles nuisibles de leur conflit, pasnécessairement l’intention en tant que telle (v◦ paragraphe (4)infra.).En effet, tout conflit armé international engendre une situationoù des personnes fuient le lieu qu’elles habitaient afin d’yéchapper. Et la situation des réfugiés qui se produitimmanquablement du conflit armé international engendre à sontour, et naturellement, une tension non-internationale dans leterritoire d’une des Parties au conflit international ou dans leterritoire d’un tiers. La situation des réfugiés engendrant unetension internationale pourrait être limitée le cas où elle seraitréglée immédiatement, et pourrait dégénérer naturellement enune tension non-internationale le cas où elle ne le serait pas12DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)immédiatement. L’observation historique des tensions noninternationalesprovoquées par des conflits internationaux,comme la situation des réfugiés provoquée par le conflit arméisraélo-arabe de 1948, affirme que des troubles intérieurs ou unconflit armé non-international seront naturellement suivis. Le casde Jordanie à la fin des années 60 ou celui du Liban durant lesannées 70, en fournit un exemple typique. Ce sont lesconséquences nuisibles naturelles d’un conflit international quiexigent que les Parties au conflit en prennent conscience et donc,en assument responsabilité. Car les Parties au conflit arméinternational n’ont le droit de décliner toute responsabilité pourles conséquences nuisibles de leur conflit dès lors que cesconséquences découlent naturellement de leur conflit. De là lespays arabes et l’État d’Israël assument responsabilité de latension non-internationale et du conflit armé non-internationalen Jordanie générés par leur conflit armé international. Aussiassument-ils, seulement indirectement, responsabilité desconflits armés non-internationaux générés au Liban parl’expulsion des Palestiniens de la Jordanie. Et le conflit noninternationalen Jordanie à la fin des années 60 qualifié d’abordde troubles intérieurs à cause de la présence armée des réfugiéspalestiniens, aboutissant par la suite à un conflit armé noninternational,ou le conflit non-international au Liban dans lesannées 70 qualifié d’abord de troubles intérieurs à cause de laprésence armée des réfugiés palestiniens, se développant par lasuite en conflits armés non-internationaux, est ce que j’appelleConflit non-international à caractère intra-national.Le conflit entre l’État d’Israël et le Hezbollah sur les territoireslibanais ne peut être qualifié de Conflit non-international àcaractère intra-national. Car pour qu’un conflit soit à caractèreintra-national il faut que sa source soit un conflit international ouun acte international par soi non-conflictuel, et que le conflit noninternationalsoit l’aboutissement naturel du conflit ou de l’acteinitial international. Or l’on peut avancer l’argument que le conflitiraélo-hezbollah est qualifié de conflit international, par l’avenuedes décisions récemment rendues par des corps judiciaires13DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)internationaux. La Cour de justice internationale souligne quel’État étranger est responsable pour le comportement d’unefaction impliquée dans une guerre civile si (a) la faction est unagent de facto de l’État étranger ou (b) l’État étranger, autrement,émet des ordres à la faction de commettre certains actes. LeTribunal pénal international pour l’ex-Yougoslavie dit, dansTadic, en 1997, que le critère « agent de facto » déclenchel’application des Conventions de Genève. Ainsi pour que le conflitisraélo-hezbollah soit qualifié de conflit intra-national, faut-il sedemander si le Hezbollah est un agent de facto de la Républiqueislamique d’Iran. Or, la doctrine du Hezbollah lui impose de sesoumettre pour toutes les décisions à caractère stratégiques au« wali el-fakih », qui n’est autre que le guide suprême de larévolution islamique iranienne (présentement l’imam Khamenei,et avant lui l’ayatollah Khomeyni). Dans son livre intitulé LeHezbollah, orientation, expérience et avenir (p. 70), Cheikh NaimKassem souligne que « ‘le wali el-fakih’ a comme prérogatives deprendre les grandes décisions politiques concernant les intérêtsde la nation (la umma), de décider des options de guerre ou depaix…» (vº L’Orient-Le Jour, vendredi 4 août 2006, p. 6). Ce quiimplique que l’autorité du « wali el-fakih » s’étend à l’ensembledes croyants chiites, nonobstant les frontières. La décision duHezbollah de poursuivre la guerre contre Israël et sa volonté demaintenir à tout prix son arsenal hors de tout consensus interlibanaisdevraient être prises en effet dans ce contexte. Or laConstitution de la République islamique mise en place en Iran aété basée sur l’allégeance au « wali el fakih ». Et nous avonsmentionné que la doctrine du Hezbollah reconnaît l’autoritéreligieuse et politique du « wali el-fakih ». En conséquence,l’allégeance réelle du Hezbollah au « wali el-fakih » l’empêche dedécliner au profit de la fondation de l’État libanais. Dans cecontexte, la République islamique mise en place en Iran serait encause. Le conflit entre l’État d’Israël et le Hezbollah est doncqualifié de conflit international, ce dernier étant agent de facto dela République islamique iranienne.14DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)Ainsi le conflit israélo-Hezbollah par lui-même n’étant pas àcaractère non-international, ne peut-il être considéré commeconflit intra-national. Mais le cas où un conflit entre des factionsarmées libanaises ou entre une faction armée libanaise et lesforces armées du gouvernement libanais éclaterait, suite à desrépercussions provoquées par le conflit isarélo-hezbollah, cesconflits non-internationaux seraient de nature intra-nationaledont le fait initial serait le conflit international israélo-hezbollah.Ce n’est pas le cas, cependant.3. Caractéristiques. Trois traits caractérisent le Conflit noninternationalà caractère intra-national:a. C’est un conflit généré naturellement par un conflitinternational ou par un acte international par luimêmenon-conflictuel;b. C’est un conflit à réaction en chaîne, c’est-à-dire seproduisant par l’intermédiaire d’une série d’étapespouvant se reproduire naturellement. Il exprime unprocessus de propagation, une suite de répercussionsprovoquée par un conflit ou un acteinitial international. Le conflit israélo-arabe de 1948fut suivi d’un exode massif des Palestiniens vers laTrabsjordanie. Le problème des réfugiés palestiniens adégénéré en un conflit non-international en Jordanie.Expulsée de Jordanie en 1970, l’Organisation delibération de la Palestine (O.L.P.) s’établît au Liban.Celui-ci dut faire face au problème soulevé par laprésence du mouvement de résistance palestinienne,qui dégénéra en un conflit non-international entre leschrétiens et les palestiniens en 1975. A partir de ceconflit d’autres conflits se reproduirent indéfiniment,comme les conflits opposant chiites et palestiniens,musulmans et musulmans, musulmans et chrétiens,musulmans et juifs, chrétiens et chrétiens, forcesarmées syriennes et chrétiens, forces armées syrienneset forces armées libanaises, forces armées israéliennes15DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)et palestiniens, etc. (v◦ A. Frangi, “TheInternationalized Non-International Armed Conflict inLebanon, 1975-1990: Introduction to Confligology”, 22CAP.U.L. REV. 965 (1993)).Non seulement le Conflit non-international à caractèreintra-national est-il:- Le résultat naturel d’un conflit oud’un acte initial international;- à réaction en chaîne; mais aussic. un conflit qui s’alimente indépendamment de lasource qui l’a généré; en ce sens que l’extinction duconflit ou de l’acte initial international n’aboutira pasnécessairement à l’extinction du conflit noninternational,puisque celui-ci est le produit desconséquences nuisibles engendrées par le conflit oul’acte initial international, et qui sont difficiles àeffacer. Le règlement du conflit israélo-palestinien oudu conflit israélo-arabe n’aurait pas mis un terme auxconflits non-internationaux entre des différentesfactions armées libanaises au Liban. Car le conflitisraélo-palestinien et le conflit israélo-arabe ontdégénéré en conflits non-internationaux entre desfactions armées libanaises qui, malgré le fait qu’ils sesont produits par l’intermédiaire d’une série d’étapesde conflits non-internationaux opposant des factionsarmées libanaises et des factions arméespalestiniennes sur le territoire libanais, ne sontcependant pas en relation avec le conflit israélopalestinienou celui israélo-arabe. Voici des exemples.(i) Le conflit opposant les Chevaliers arabes a<strong>law</strong>iteslibanais à la milice du Mouvement d’unificationislamique, le Tawhid islami, à la fin de l’année 1983, àTripoli. (ii) Le conflit entre le Hezbollah et la miliced’Amal, en avril 1988, dans le sud du Liban et dans lesbanlieues de Beirut. (iii) Les conflits opposant lesPhalanges aux militants musulmans entre 6 décembre16DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)1975 et juillet 1976, dans l’ouest de Beyrouth et àDamour. (iv) La ‘Première guerre maronite’ entre lesforces armées du Parti des Phalanges et l’Armée deLibération Zghortiste, entre 1976 et 1979, dans le norddu Liban. (v) La ‘Deuxième guerre maronite’ entre lesforces armées du Parti des Phalanges et les forcesarmées du Parti de libération nationale, en juillet 1980(Opération 7/7/80), dans l’est, le nord-est et le nord deBeirut.Ainsi, ce qui distingue essentiellement le Conflit noninternationalà caractère intra-national du Conflit noninternational‘positif’ et des expressions politiques susmentionnées,est qu’il est l’aboutissement naturel d’un conflitinternational ou d’un acte international par soi non-conflictuel.Les Parties au conflit ou à l’acte international qui a dégénéré enun conflit non-international peuvent savoir et sont tenues desavoir les conséquences naturelles nuisibles de leur conflit.Aucune Partie au conflit n’est censée les ignorer.4. Responsabilité: Le Conflit non-international à caractèreintra-national peut se présenter de trois façons. Tout d’abord, ilpeut être anticipé et délibéré par les Parties au conflit ou à l’acteinternational. C’est le cas des Parties qui agissent avec le savoirque le conflit international qu’elles engagent ou l’acteinternational qu’elles commencent dégénérera, tôt ou tard, le casoù le dommage causé ne serait pas réduit, en un conflit noninternational.En ce cas, la grandeur du dommage, i.e., réfugiés,tension interne ou troubles intérieurs, contribue directement àaggraver la responsabilité des Parties, le dommage qu’ellescausent étant par soi l’objet même du conflit ou de l’acteinternational.Ensuite, le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-nationalpeut être anticipé mais pas délibéré par les Parties au conflit ou àl’acte international; par exemple lorsque ces dernièrescommencent un acte international qui s’avère nuisible ou17DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)commettent de graves méfaits sciemment pour aboutir leursobjectifs militaires, bien que sans dessein de causer un conflitnon-international. En ce cas, la quantité du dommage contribueindirectement à aggraver les circonstances du conflit ou de l’acteinternational; car le fait de ne pas hésiter à commettre des méfaitsque les Parties ne voudraient pas faire sans leur conflitinternational ou leur acte international, reflète une volontéinclinée à nuire.Enfin, le Conflit non-international à caractère intra-national n’estni anticipé ni délibéré par les Parties au conflit ou à l’acteinternational. En ce cas, le dommage causé n’aggrave pas lescirconstances du conflit ou de l’acte initial international.Néanmoins, en raison de la négligence Parties à envisager lesconséquences fâcheuses de leur conflit ou acte international, ledommage les rend responsables sans qu’elles l’aient fait à dessein,dès lors qu’elles engageaient un conflit international par luimêmedéfendu ou commençaient un acte international par soinon-défendu mais qui risque toutefois d’être nuisible. Cependant,les circonstances du conflit ou de l’acte international s’aggraventdans le cas du conflit non-international à caractère intra-national.Car si le dommage est par lui-même une suite naturelle du conflitou de l’acte international, comme c’est le cas du Conflit noninternationalà caractère intra-national, bien qu’il ne soit nianticipé ni délibéré, il aggrave directement les circonstances duconflit ou de l’acte international, par là aggravant laresponsabilité des Parties au conflit ou à l’acte international, carce qui est par soi-même une dégénération du conflit ou de l’acteinternational tombe, en quelque manière, dans le champs plutôtlégal que non-légal de ce conflit ou de cet acte (concernant ladistinction entre les concepts ‘legal’, ‘illégal’ et ‘non-légal’ v° A.Frangi, « The Intra-Nationalized International Conflict », FreeL.J. 2005 1(2), note 5).5. Conclusion: Le Conflit non-international à caractère intranationaldoit être imputé aux Parties au conflit ou à l’acteinternational d’autant plus gravement que ces Parties ont plus de<strong>18</strong>DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)puissance mondiale. Quand les Parties au conflit ou à l’acteinternational occupent une place primordiale mondiale, et quandun conflit non-international à caractère intra-national peut êtreprésenté des trois façons sus-mentionnées, la délibération ou lanégligence de ces Parties est un scandale dangereusementmondial, car l’injustice des grandes puissances fait que les genss’en indignent davantage. Ainsi le conflit non-internationalgénéré par des Parties au conflit ou à l’acte international, qui sonten honneur mondial, leur est plus sérieusement imputé à mal,leur puissance mondiale étant une cause de responsabilitéaggravante.19DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)20DR ANWAR FRANGI - LE CONFLIT NON-INTERNATIONALÀ CARACTÈRE INTRA-NATIONAL

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW ORVIOLATION OF STATE’S LAW?ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOMBy Dr. Saim ÜYE *INTRODUCTIONBeing structured around a variety of social control mechanisms,the social life comprises lots of socio-cultural norms that forcehuman beings to be in line with the justified ways of behaving.Living steadily as a member of a society or a social group ispossible only by conforming the pre-established rules of conduct.Non-conformity results in facing sanctions and these sometimescause to end one’s life. The society reaffirms the values attributedto the norms by way of getting rid of the very existence of thedisobedient. The “killings based on custom” observed in some –especially middle eastern– cultures represent the situation of thiskind.Strict customary practices, which justify killings decisively as asanction for the deviants of the customary code, are held generallyin relation with the concept of “honour”. In literature there seemsto be a general usage of the term “honour killings” to desribe thewide range of such commitments. It must be stated here that thereare differences between so called “honour killing” and “killingbased on custom”. Though both are related with the concept ofhonour, the former has excessively individual, not collectiveaspects. What makes the latter different is that it includes decisionsof family (or tribal) counsels; that is family (or tribal) counsels* PhD, Ankara University, Faculty of Law, Turkey.21DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)gather and decide whether the customary rules are violated by theact or not and what the sanction thereof shall be.The issue may be examined as a problem of the criminal <strong>law</strong>,because the activities of these counsels are considered as criminalin formal legal texts. But this is not the main point here. It must beseen that these unofficial counsels act effectively like a court eventhough they are disapproved and criminilized by the state’s legalsystem. These court-like bodies constituted in the social realitymake the situation to be worthy of being examined from the pointof view of sociological and anthropological studies. The aim of thisarticle is to discuss briefly the theoretical place of such kind ofevents with regard to the conceptual framework improved bysociology and anthropology of <strong>law</strong>. This is obviously a descriptivebut not a problem-solving perspective.KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM AS A PART OF SOCIALREALITYCommon PointsA review of exemplary events from three countries –Turkey,Pakistan and India–may help to illustrate the issue in question.“Her name is Hacer; she is 16. She asked for a love song tobe played on the radio on March 2, 1984. The same nightshe ran away from home, but she was quickly found bythe police who returned her to her father just like a parcel.She was brought home where her father and uncles weregathered, and she was locked in a small room while themale members of her family decided on her fate. Despiteher father’s objections, the decision was made that shemust be killed; otherwise, the rest of the family would notbe able to look others in the community in the eye. The22DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)lethal task was awarded to a 13-year-old boy, the youngestmale member of the family. He shot his sister in coldblood. 1 ”“According to the information received, on May 4, 2004,Ms Tahmeena (17) and Ms Aabida (<strong>18</strong>), who are cousins,were shot to death after having been accused of having“loose morals” for having visited their grandparentswithout permission. The decision to kill the girls wastaken in a tribal jirga, convened amongst the perpetratorsand led by Mr Abdul Rasheed, the tribal chief and apowerful landlord in the village....The information also indicates that cases of crimescommitted in the name of honour are generally ruled bythe landlords (Jirga-tribal court) in the Sindh Provincerather than by the courts of <strong>law</strong>. 2 ”“Fifteen inhabitants of a village in Haryana (NorthernIndia) were charged with murder. They had stoned andstabbed to death two young lovers who refused to endtheir relationship. The young man was called before avillage counsel where he was beaten to death with theapproval of his family. After the execution, the two bodieswere brought to a cremation area outside the village.When the police arrived, they only found the burnedremains of the two victims 3 ”.Lots of similar stories may be heard from different countries.1 Canan Arin, “Femicide In The Name of Honour in Turkey”, Violence AgainstWomen, Vol.7 No.7, July 2001, p. 821.2 http://www.peacewomen.org/news/Pakistan/May04/twogirls.html3 From a Belgian newspaper De Standaard, cited in Jeroen Van Broeck,“Cultural Defence and Culturally Motivated Crimes (Cultural Offences)”,European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, Vol. 9/1, 2001,p. 1.23DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)However, for the purpose of this article, the common elements ofall these may be figured out as follows:a) Existence of a rule of conductb) Commitment of an act not conforming with the rule of conductc) Gathering of a counseld) Triale) Decision for punishmentf) ExecutionIt is not hard to see the strong resemblance between this practiceand the official enforcement of the state’s legal norms. Thecounsels seem to take the place of the state’s courts and the samesteps seem to be taken actually to produce the same results, eventhough one is officially justified while the other is not.Comparison with the StateThe elements of the two practices may be examined as comparedwith each other :CUSTOMARY PRACTICE STATE’S PRACTICENorm Customary Honour Code Penal CodeViolation of the Dishonourable Conduct CrimeNormAuthority Family (or Tribal) Counsel CourtTrial Unofficial Trial Official TrialDecision Punishment PunishmentCommand of To a member/members of the To the official organsExecution family (or the tribe)Execution Unofficial Execution Official ExecutionTable: The parallel patternsThere are norms –written or unwritten, but well-known– on bothside, in case of violation of which an authority is expected to have24DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)a trial and reach a decision that is to be carried out by force. Asfar as effectivity is concerned, customary practices are notweaker, if not stronger, than the other, as a consequence of beingnaturally closer to the face to face interactions of the people indaily life.In legal doctrine, the widespread opinion has long been that one ofthese parallel patterns running side by side effectively, that of thestate’s, is qualified to be called as “<strong>law</strong>” and the other not. Thisstems from the conventionally accepted thought that identifies“<strong>law</strong>” with “state”.Social scientific approaches, however, point another direction.SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTUALIZATION OF LAWOwing to the sociological and anthropological studies, it is claimedthat involvement of the state in the production and enforcement ofnorms shall not be seen as a prerequisite condition for being calledas “<strong>law</strong>”. Accordingly, social reality itself is considered to becapable of producing <strong>law</strong> independently from the state. The viewsof some of the distinguished scholars may be shortly rememberedin this context.Weber : “Extra-State Law”Max Weber denies to identify the <strong>law</strong> with the state. He calls anorder as <strong>law</strong>, “if it is externally guaranteed by the probability thatcoercion (physical or psychological), to bring about conformity oravenge violation, will be applied by a staff of people holdingthemselves specially ready for that purpose 4 ”.4 Max Weber, Law in Economy and Society, tr: Edward Shills and MaxRheinstein, Harvard University Press, Cambridge – Massachussets, 1954, p. 5.25DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)Neither the staff emphasized in the definition ought to be theofficial organs of the state, nor the coercive power the monopoly ofthese organs. The sociological definition also covers other socialgroups and associations having coercive means for theenforcement of their norms. Accordingly, Weber indicates that ifthe means of coercion are at the disposal of some authority otherthan the state then we shall speak of “extra-state <strong>law</strong>” 5 .“Extra-state <strong>law</strong>” may be in contradiction with the “state <strong>law</strong>” andwhere it is not, it does not need the guaranty of the state. Thispaves the way for an order of a social group to be qualified as a“legal order” and to be acknowledged without necessarily referringto any activity of the state 6 .Ehrlich : “Living Law”Eugen Ehrlich agrees with the opinion that, being created by thestate or being the basis for the decisions of the state’s courts is nota necessity for an order to be recognized as <strong>law</strong> 7 . Ehrlich sees “thebasic form of <strong>law</strong>” as “the inner order of the associations of humanbeings” 8 . “A social association is a plurality of human beings who,in their relations with one another, recognize certain rules ofconduct as binding, and, generally at least, actually regulate theirconduct according to them. 9 ”The legal system of the state is composed of legal propositions.“The legal proposition is the precise, universally bindingformulation of the legal precept in a book of statutes or in a <strong>law</strong>5 Ibid, p. 16, 17.6 Ibid, p. 17.7 Eugen Ehrlich, Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law, tr: Walter L.Moll, Russel & Russell Inc., New York, 1962, p. 24.8 Ibid, p. 37.9 Ibid, p. 39.26DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)book. 10 ” But legal propositions do not have the same meaning aslegal norms. The criteria for being considered as a legal norm isthat of “actual effectiveness”. That is, the legal propositions whichare not only stipulated in <strong>law</strong> books but also really effective onhuman life shall be considered as legal norms. On the other hand,there are many effective rules in the associations of human beingswhich actually regulate the conduct of their members but do nottake any place in <strong>law</strong> books. These are the rules arising from thevery core of the social life itself. That is why “in every society thereis a much greater <strong>number</strong> of legal norms than of legalpropositions. 11 ”To what attention must be paid is the “living <strong>law</strong>” rather than whatis written in official texts. “The living <strong>law</strong> is the <strong>law</strong> whichdominates life itself even though it has not been posited in legalpropositions. The source of our knowledge of this <strong>law</strong> is, first, themodern legal document; secondly, direct observation of life, ofcommerce, of customs and usages, and of all associations, not onlyof those that the <strong>law</strong> has recognized but also of those that it hasoverlooked and passed by, indeed even of those that it hasdisapproved” 12 .Gurvitch : “Spontaneous Law”Georges Gurvitch considers the opinion that regards the state asthe institution having both political and jural sovereignity as an“optical illusion” 13 . According to Gurvitch, normative facts, i.e.social facts having the capacity to produce <strong>law</strong>, are the most10 Ibid, p. 38.11 Ibid, p. 38.12 Ibid, p. 493.13Georges Gurvitch, Sociology of Law, Transaction Publishers, NewBrunswick and London, 2001, p. 253.27DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)immediate data of jural experience 14 and social groups are specificnormative facts in this manner. After pointing that “There is noobservable society which does not include a multiplicity ofparticular groups” 15 , Gurvitch claims,” Every group in which activesociality predominates and which realizes a positive value ...affirms itself as a ‘normative fact’ engendering its own juralregulation” 16 .“Active sociality” refers to a thought of having something to bedone, a duty to be performed together and “positive value” means asocially recognized “good” that is supposed to be realized in the lifeof the particular group 17 . Different types of the social groups, inaccordance with their special qualities, are capable to produce theirown “frameworks of <strong>law</strong>” <strong>18</strong> .Closely related with these assessments, Gurvitch contends thatthere is a “spontaneous” level in the life of <strong>law</strong> as opposed to the“organized” 19 . When speaking of the <strong>law</strong> which arises from theformer level, Gurvitch uses the term “spontaneous <strong>law</strong>”, which maybe recognized and described just in the same way as the “organized<strong>law</strong>” of the state 20 .Pospisil : “The Legal Systems of Subgroups”Basing his views on anthropological studies, Leopold Pospisilargues that any human society “... does not possess a singleconsistent legal system, but as many such systems as there are14 Ibid, p. 53.15 Ibid, p. 232.16 Ibid, pp. 241, 242.17 Ibid, p. 201.<strong>18</strong> Ibid, pp. 242-250.19 Ibid, pp. 222, 223.20 Ibid, pp. 226-229.28DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)functioning subgroups. Conversely, every functioning subgroup ofa society regulates the relations of its members by its own legalsystem, which is of necessity different, at least in some respects,from those of the other subgroups. 21 ”According to Pospisil, there are certain attributes which mustcoexist in order to provide the essence of <strong>law</strong>. He lists the fouressential “attributes of <strong>law</strong>” as authority, intention of universalapplication, obligatio and sanction 22 . “Authority” is an individualor a group of individuals, who have the power to make a decisionand to have it obeyed even in cases where it faces resistance ofthose to whom the decision is related 23 . “The intention of universalapplication” points that the decision is taken with the intentionthat it shall be applied in all cases of similar kind which may takeplace in the future 24 . “Obligatio”, differing from ‘obligation’, meansthat the decision states or implies that a party is under a duty as aresult of his/her act; while “sanction”, included in the decision,shows what is to be done in order to have the situation corrected 25 .Consequently Pospisil calls <strong>law</strong> “... as principles of institutionalizedsocial control, abstracted from decisions passed by a legal authority(judge, headman, father, tribunal, or council of elders), principlesthat are intended to be applied universally (to all “same” problemsin the future), that involve two parties locked in an obligatiorelationship, and that are provided with a sanction of physical ornonphysical nature. 26 ”Since in every subgroup of a society where these attributes areobserved we confront with a specific legal system; we can speak of21 Leopold Pospisil, Anthropology of Law, A Comparative Theory, Harper &Row Publishers, New York, pp. 98, 99.22 Ibid, p. 43.23 Ibid, p. 44.24 Ibid, p. 79.25 Ibid, pp. 82, 83.26 Ibid, p. 95.29DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)the society as composed of “the multiplicity of legal systems” 27 .Hence, an individual may be said to be subject to “all the differentlegal systems of the subgroups to which he is a member 28 ”.CONCLUSIONSociological and anthropological studies of <strong>law</strong> provide us with apluralistic point of view, acknowledging the fact that social groupsare capable of producing <strong>law</strong>. Killings based on custom addressedabove are hence qualified to be recognized as a practice of “<strong>law</strong>”, asproduced by the kinship groups or tribes, in this sense. Thecoercive means are at the disposal of the family (or tribal) counsels,which are ready to use these means in case of violation of norms(Weber). These norms are effectively regulating the conduct of thegroup’s members, that is they are “living” in the observable realityof social life (Ehrlich). The practice is based on an active socialityand the group attributes a positive value to it (Gurvitch). Thecounsels represent the authority, decisions of which, as reached tobe applicable in all the same cases, include the attributes ofobligatio and sanction (Pospisil).No matter it is called as “extra-state <strong>law</strong>” or “living <strong>law</strong>” or “spontaneous <strong>law</strong>” or “legal system of a subgroup”, we mayconclude that killings based on custom represent an order that maybe called sociologically as “<strong>law</strong>”, taking place in the societyeffectively besides the <strong>law</strong> of the state, though being criminalizedby the latter. Socio-legal pluralism helps us to avoid associating“legal order” exclusively with the “legal order of the state” and tounderstand the situation where the same act may be considered asenforcement of a legal order (tribe’s <strong>law</strong>) while possibly beingregarded as violation of another (state’s <strong>law</strong>) at the same time.Observing the continuous practice of killing someone who failed to27 Ibid, p. 112.28 Ibid, p. 107.30DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)obey the costomary honour code as a socially acceptedpunishment, on the other hand, shows that the “death penalties”may continue to live in the legal systems of social groups, though itis removed officially from the state’s (e.g. Turkey’s) legal system.It must be made clear at this point that calling the mentionedpractices as “<strong>law</strong>” is on no account followed by an implied approvalof these killings. Because, as Gurvitch rightly states, "The act ofrecognizing facts which realize values is quite different from directparticipation in these values 29 ”. Scientific description differs fromethical justification. Ongoing struggle against killings based oncustom or so called “honour killings” in general, at national andinternational level, may be the subject of another article.29 Gurvitch, op.cit., p. 53.31DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)32DR. SAIM ÜYE - ENFORCEMENT OF TRIBE’S LAW OR VIOLATIONOF STATE’S LAW? ON KILLINGS BASED ON CUSTOM

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)BASES FOR THE EXCLUSION OFTHE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA ANDHERZGEGOVINAByBORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD* ANDDRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ PHD**Introductory remarksLack of any of general, basic elements of the definition of thecriminal act, of objective or subjective character, exempts that act(that is, the act committed by a person, with resultingconsequences) from the character of criminal act 1 . It is regardedto the circumstances which an act of a man exempts from eithersocial danger or illegality, or of both elements. Namely, theexclusion of these elements exists when the act, which isotherwise regulated by <strong>law</strong> as a criminal act, is considered asexcusable, according to some special provision. Provisions whichallow this otherwise “forbidden” act in a specific case excludeillegality, so that there is no criminal act in that case.There are two bases for the exclusion of the criminal act in thecriminal <strong>law</strong> of Bosnia and Herzegovina. They are: 1) generalbases ( which are specifically provided by <strong>law</strong> and may be foundin any criminal act or for any perpetrator) and 2) special bases (* Borislav Petrović PhD, Associate Profesor, Faculty of Law inSarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and** Dragan Jovašević PhD, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law in Niš,Republic of Serbia.1D. Jovašević, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Nomos, Beograd, 2006. p. 87-8833BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)which are not specifically provided by <strong>law</strong> and could not be foundin any criminal act or for any perpetrator) 2 .General bases in the criminal <strong>law</strong> of the Bosnia and Herzegovinaare:1) small insignificance or act of little significance 3 (article 25. ofthe Criminal code of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 4 ,article 25. of the Criminal code of the Brčko District of Bosnia andHerzegovina 5 and article 7. paragraph 2. of the Criminal code ofthe Republic Srpska 6 ),2) necessary defence (article 24. of the Criminal Code of theRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovina 7 , article 26. of the Criminalcode of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, article 26. ofthe Criminal code of the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand article 11. of the Criminal code of the Republic Srpska) and3) extreme necessity (article 25. of the Criminal code of theRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, article 27. of the Criminalcode of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, article 27. ofthe Criminal code of the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand article 12. of the Criminal code of the Republic Srpska).Special bases for the exclusion of the criminal act are notspecifically provided by <strong>law</strong>. They present a creation of the <strong>law</strong>theory and court practice (but some of them are seen in the2B. Petrović, D. Jovašević, Krivično (kazneno pravo) Bosne i Hercegovine, Općidio, Pravni fakultet, Sarajevo, 2005. p.1553E. Foregger – E. Serini, Strafrecht Gesetzbuch, 9. Auflage, Wien, 1989. p.53-544Službene novine Federacije Bosne i Hercegovine broj : 36/2003, 37/2003,21/2004 i 69/20045Službeni glasnik Brčko Distrikta Bosne i Hercegovine broj : 10/2003 i 45/20046Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske broj : 49/2003 i 108/20047Službeni glasnik Bosne i Hercegovine broj : 3/2003, 32/2003, 37/2003,54/2004 i 61/200434BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)foreign legislations in specific cases) 8 . Specific bases usuallyinclude: 1) assent of the inflicted, 2) self-infliction, 3) performingthe official duty, 4) superior’s order, 5) the right for disciplinaryor corrective punishment and 6) allowed risk. According to thefact that these special bases are not specifically provided by <strong>law</strong>,their effect and applicability are of controversial matter 9 .1. THE CRIME OF SMALL SIGNIFICANCE 10In the article 25. of Criminal code of the Federation of Bosnia andHerzegovina, article 25. of the Criminal code of the Brčko Districtof Bosnia and Herzegovina and article 7. paragraph 2. of theCriminal code of the Republic Srpska there is anticipated that theactivity can not be considered as a criminal if it has smallsignificance, no matter if it has characteristics of the crimedefined by the <strong>law</strong>. Such situation can be solved by applying theprinciple of opportunity of the criminal persecution by theprocess mean in accordance with the provisions of the criminal<strong>law</strong> in Bosnia and Herzegovina about the criminal process.For this institute existence there is necessary three conditions tobe cumulatively fulfilled:1) that the level of the committer guilt is low,2) that the harmful consequence of the crime in inconsiderable orlacking and8P. Novoselec, Opći dio kaznenog prava, Zagreb, 2004. p.162-1639Z.Stojanović, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Beograd, 2005.p.14810This general base for the exclusion of the criminal act defines several moderncriminal codes : article 28. of the Criminal code of the Republic of Croatia,article 36 of the Criminal code of the Russian Federation, article 8 of theCriminal code of the Republic of Macedonia, article 9 of the Criminal code of theRepublic of Montenegro and article 14 of the Criminal code of the Republic ofSlovenia35BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)3) if the general purpose of the criminal sanctions does notrequire the criminal sanction sentencing.2. NECESSARY DEFENCEAccording to provision article 24. of the Criminal Code of theRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, article 26. of Criminal codeof the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, article 26. of theCriminal code of the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand article 11. of the Criminal code of the Republic Srpska,necessary defence is defence which is necessary for a perpetratorin order to protect himself or other person from an imminentillegal attack. It is a second base for the exclusion of the criminalact in criminal <strong>law</strong> in Bosnia and Herzegovina 11 .An act committed in necessary defence 12 is excusable because thelegislator himself considers that the perpetrator of such act isauthorised for commission of that act. From this definition, itresults that necessary defence, in the sense of institute of criminal<strong>law</strong>, has to fulfil two conditions-the existence of attack andprotection from such attack. But not every attack gives the rightfor necessary defence, nor every protection from attack is11This base prescribes many modern criminal codes on similar way : article 29of the Criminal code of the Republic of Croatia, article 37 of the Criminal code ofthe Russian Federation, article 22 of the Criminal code of the Republic of Israel,article 15 of the Criminal code of the Republic of Ukrain, article32 of theCriminal code of Federal Republic of Germany, article 12 of the Criminal code ofthe Republic of Bulgaria, article 9 of the Criminal code of the Republic ofMacedonia, article 22 of the Greek Criminal code, article 13 of the Criminal codeof the Republic of Belarus, article 11 of the Criminal code of the Republic ofSlovenia and article 19 of the Criminal code of the Republic of Albania12More : V. Timoškin, Nužna odbrana, Sarajevo, 1939. ; B: Ignjatović, Nužnaodbrana u teoriji i praksi, Doboj, 1967.; D. Jovašević, T. Hašimbegović, Osnoviisključenja krivičnog dela, Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja,Beograd, 2001. ; V. Đurđić, D. Jovašević, Lj. Zdravković, Nužna odbana ukrivičnom pravu, Niš,2004.36BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)necessary defence. Attack, as well as protection from attack, hasto fulfil conditions cumulatively provided by <strong>law</strong>.2.1. Conditions for the existence of attackAttack is every act aimed towards violating or endangering legalproperty or legal interest of a person 13 . It is most oftenundertaken by action, and sometimes by inaction. In order for anact to be relevant with the view to institute of necessary defence,it has to fulfil certain conditions, which are: attack has to beundertaken by man; attack has to be aimed against any legalproperty or legal interest of a person; attack has to be illegal; andattack has to be real 14 .1) Attack can only be undertaken by man.-If an act is notundertaken by man but by an animal or by a force of nature, thenthere is the existence of danger as an element of extremenecessity, but not as well necessary defence. However, if a persondirected a force of nature (torrent, rockslide) in order to endangerother person or his legal property, or if an animal (a dangerousdog or a horse) is used as means for endangering protectedproperty, than these cases are also considered as necessarydefence. Attack could be undertaken by any person, no matter ofthe age, accountability or guilt. It could be undertaken by anyaction or inaction, as well as using any means which is suitablefor violation or endangering some legal property 15 .13J. Šilović, Nužna odbrana, Zagreb,1910.p.9714M. Tomanović, Nužna odbrana i krajnja nužda, Beograd, 1995.; D. Jovašević,Krivičnopravni značaj instituta nužne odbrane, Pravni zbornik, Podgorica, No, 1-2/1998. pp.128-143; D. Jovašević, Pravo na život i nužna odbrana, Pravni život,Beograd, No. 9/1998. pp.43-6115P. Novoselec, Krivično pravo, Krivično delo i njegovi elementi, Osijek,1990.p.35-3637BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)Therefore, necessary defence is excusable in case of an actualattack (instantaneous or present), as well as in case of imminentattack. Whether the attack is imminent, is a question which isdetermined by court in each particular case, judging all thecircumstances of the committed act and the perpetrator. Theattack is imminent when there is a possibility (in time and place)of the close carrying out an attack 16 . But, it does not mean thatnecessary defence is excusable against future, undetermined inplace and time, but indicated attacks. Measures of precaution andpreventive protection against indicated or expected attacks areexcusable only if they do not go over the limits of necessarymeasures for that specific moment.2) Attack has to be aimed against a person, his legal property orlegal interest.-Attacked or endangered properties, in the sense ofnecessary defence, could be different. Most often, life andphysical integrity is being attacked, but sometimes it can beproperty, honour, reputation, dignity, moral. The object of attackcould be any legal property or legal interest. Law does notexplicitly state which are those goods that can be the objects ofattack in the sense of necessary defence. Attack can be aimedagainst any legal property of the attacked person, but also againstany legal property of some other physical or legal person. In thatway, attack can be aimed at violating the property of acorporation, facility or some other organization, but also againststate security and its constitution 17 .Therefore, necessary defence exists not only in case of protectingfrom the attack on a legal property, but also in case of protectingfrom the attack on any property of other person (physical or legal)if that person is not capable of protecting himself from suchattack. There are theories in criminal <strong>law</strong>, according to which16T. Živanović, Krivično pravo Kraljevine Jugoslavije, Opšti deo, Beograd,1935.p.23117B. Petrović, D. Jovašević, Krivično (kazneno) pravo Bosne i Hercegovine, Općidio, Pravni fakultet, Sarajevo,2005. p.146-14938BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)some cases of protecting from the attack are not considered to benecessary defence, but called “necessary help”. In any case, thescope and necessity of defence depend in the first place on thenature of legal property which is attacked or endangered.3) Attack has to be illegal.-Attack is illegal when it is not based onsome legal regulation and when it is not undertaken on the basesof some legal authorisation. Therefore, attack which isundertaken during exercising duty according to some legalauthorisation, is not illegal and necessary defence in that case isnot excusable. However, if an authorised person oversteps thelimits of legal authorisation, then such situation is changed intoillegal attack against which necessary defence is allowed. On theother hand, violation of necessary defence also changes intoillegal attack, in which case the attacker has the right for defence(because in this case he is in the state of necessary defence).The right for necessary defence exists no matter if the attacker isconscious of illegality of his attack or not. Namely, it is enoughthat the attacked person objectively realises the attack. It is of nosignificance whether the attacker is guilty or not, as well aswhether his act is punishable. Illegal attack could be undertakenby a child or by a mentally incompetent person. That means thatnecessary defence on necessary defence is not excusable. But,different situations in life can happen, when the attacked personanticipates the possibility of being attacked in certain place andtime because of his relationship with some person. If in suchsituations anticipated attack is undertaken, it is considered asillegal <strong>18</strong> .Even more controversial situation is when a person provokesattack. There is no dilemma if the attacked person had previouslyendangered someone’s integrity or property. The problem arisesif such attack is manifested verbally or only with concluding acts<strong>18</strong>M. Radovanović, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Beograd, 1975. p.9539BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)which irritate, provoke or underestimate the attacker 19 . Socialcomponent of the institute of necessary defence should beconsidered in such situations. Namely, necessary defence standsfor protecting the rights from illegality, and because of that abuseof this institute is not excusable. If the attacked person haddeliberately provoked the attack, so as to use it and violate theattacker or his property, than the attacked person has no right onnecessary defence. Such cases are known as feign necessarydefence 20 .4) Attack has to be real.-Namely, it has to exist really in theoutside world. It means that it is necessary that the attack hasalready started or it is imminent. Whether an attack exists or not,is a factual question which is being solved by court in eachspecific case. Typical example of real attack is endangering life ormaking physical injuries to a person. If there is no real attack, butthe attacked person had a wrong or incomplete impression orillusion of its existence, there is no basis for necessary defence. Insuch case there is putative, imaginable or ostensible necessarydefence. This defence does not exclude the existence of a criminalact, but it could be a ground for exclusion of the guilt 21 .Therefore, putative necessary defence represents, in fact, the lackof conscience of the attacked person about some realcircumstance of the attack. That is, in fact, wrong impression andconviction that the attack aimed at violation of some property isreal. This mistake could be related to the conscience about theillegality of the attack (when there is legal mistake). In otherwords, putative necessary defence is reduced to unavoidablemistake, in broader or narrower sense that the attacked person isin a condition of real and objectively needed necessary defence.When judging the existence of necessary defence or its violation,19F. Antolisei, Manuale di diritto penale, Parte generale, Milano, 1997.p.192-19320Lj. Bavcon, A. Šelih, Kazensko pravo, Splošni del, Ljubljana, 1987, p.15121Z. Stojanović, Komentar Krivičnog zakona SR Jugoslavije, Službeni list,Beograd,1999. p. 22-2440BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)an act has to be seen on the whole, which means that it cannot bereduced and limited to only what had happened between thedefendant and late (that is, the one who has suffered loss)immediately before the gun shot.2.2. Conditions for the existence of defenceDefence or protection from the attack is every action of theattacked person aimed at eliminating, preventing or protectingfrom the attack. By protection from the attack, the attackedperson himself violates or endangers some legal property of theattacker. This violation or endangerment represents, in essence,formal characteristics of some criminal act from the special partof criminal codes in Bosnia and Herzegovina (most often it isabout a criminal act against life or physical integrity) 22 .Only in case when the attacked person, during the protectionfrom attack, violates some property of the attacker, the existenceof the institute of necessary defence is possible 23 . Necessarydefence is not only the defence from the attack which endangerssecurity of life of the attacked person, but every defence frompresent and illegal attack, if such defence was necessary forprotection from the attack.For the definition of needed defence, in the sense of penal <strong>law</strong>, itis absolutely necessary that the illegal attack is protected from bya punishable act towards the attacker. If such protection wouldnot be considered as a punishable act, then it would be a situationbeyond the area of penal <strong>law</strong> 24 . Defence, as an element ofnecessary defence, as well, has to fulfil certain conditions in order22N. Srzentić, A. Stajić, Lj. Lazarević, Krivično pravo SFRJ, Opšti deo,Savremena administracija, Beograd, 1978.p.17123G. Marjanovik, Makedonsko krivično pravo, Opšt del, Prosvetno delo, Skopje,1998.p.<strong>18</strong>324Đ. Avakumović, Teorija kaznenog prava, Beograd, <strong>18</strong>87-<strong>18</strong>89.p.27941BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)to be of criminal legal relevance. These conditions are: defenceconsists of protection from the attack; defence has to be aimedagainst the property of the attacker; defence has to besimultaneous with the attack, and defence has to be necessary forthe protection from attack 25 .1) Defence has to be consisted of protection from the attack.-Ifdefence is not aimed at protection or prevention of attack, than itis not an element of necessary defence. Defence, in fact, dependson the existence of attack. The kind of defence has to be accordingto the attack. Attacked person is not obliged to retreat before theattacker. On the contrary, he is authorised to frustrate and disablethe real illegal attack, in the aim of defence of legal property, bysimultaneous legal attack on the attacker’s legal property.2) Defence has to be aimed against the attacker and against anyof his legal property or legal interest.-These properties could bevarious, like: life, body, estate, honour, reputation, humandignity, though most often situation is when life of the attacker isviolated. But, there are situations in life, when it is about theviolation or endangering legal property and the attacker, as wellas some other person. Then, in relation to the property of theattacker, the attacked person acts in necessary defence, and inrelation to the violation of property of some other person, he actsin extreme necessity (if all the conditions provided by <strong>law</strong> arefulfilled) 26 . That means that the attacked person, in order toprotect his property, cannot put to extreme risk legal properties ofother people. But, if the attacker had used properties of otherperson while committing an illegal attack as means of that attack,then, in case of violation those properties, there is necessarydefence 27 .25P. Novoselac is thinking differently (P. Novoselac, Opći dio kaznenog prava,Zagreb, 2004. p.170-17426Strafgesetzbuch Leipziger, Kommentar, Berlin-New York, 1985. p 16327D. Jovašević, T. Hašimbegović, Osnovi isključenja krivičnog dela, Institut zakriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, Beograd, 2001.p.5042BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)3) Defence has to be simultaneous with attack.-Defence issimultaneous if it was undertaken at time when attack has beenimminent or when it began, but only up to the moment when itceased. Attack is imminent when, from all the circumstances, itcould be concluded that it was about to start, and when there wassuch danger that violation of legal property would occur in thenext moment. The beginning of an act which could have directconsequences (death, physical injury, taking away, destroying ordamaging property) is not crucial for beginning of the attack.Undertaken action which objectively represents imminent sourceof danger is essential.Whether an attack is imminent or not is a factual question whichis being solved by court in each particular case. Only threat ofimminent attack, without undertaking previous actions fromwhich it can be concluded that the attack was imminent, couldnot be the reason for undertaking the act of defence. Defence offuture attack is not excusable either, but still undertaking of somemeasures of precaution and some protective measures which startto work automatically in the moment when the attack starts (likevarious alarm systems connected with electrical circuit) isallowed.When the attack has started, defence could begin in the samemoment. But, it often happens that the attacked person is not inposition to react at the same time when the attack starts. In thatcase defence could be undertaken at any time during the attack.Continuity of defence has to coincide with the continuity ofattack. When the attack has stopped, the right of the attacked onnecessary defence stops, too.An attack was ended if legal property of the attacked person hasbeen violated and when danger has been caused (as a kind ofconsequence in cases of criminal acts of endangering), and whenthe attacker has committed the action of attack, but due to43BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA

FREE LAW JOURNAL - VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 (<strong>18</strong> JANUARY <strong>2007</strong>)accidental circumstances there was no violation of property of theattacked person. The right for necessary defence stops if theattack has finally and definitely ceased, but not in case when theattack was only temporarily ceased. Whether an attack has ceasedor only temporarily ceased is a factual question which is beingsolved by court in each particular case. Attack has temporarilyceased if there is a possibility that it could be continued anymoment.4) Defence has to be necessary for protection from attack.-It isthe defence which exists in case when attack cannot be preventedfrom in any other way except for violating the attacker’s property.This means that violation of attacker’s property has to benecessary, unavoidable in order to protect from the attack, so theintensity of defence is correspondent to the intensity of the attackand the manner and means which were used by attacker. Whenjudging this necessity of defence, the equivalence betweenintensity of attack and intensity of defence in each particular caseshould be taken into consideration 28 . On the other hand, thisproportion means that violation of the attacker’s property isproportional with value of the property of the attacked personwhich was saved in this way 29 .2.3. Violation of necessary defenceIf an attacked person, during the protection from attack on his orsomeone else’s legal property, oversteps the limits of defencewhich is necessary for protection from that attack, there isviolation or excerpt of necessary defence has prescribed in article24. paragraf 3. of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Bosnia and28P. Novoselac, Opći dio kaznenog prava, Zagreb, 2004. p.33; F. S. Pierra, LaGuide de la defense penale, Paris,2003.p.59; H.H. Jescheck, Lehrbuch desStrafrechts, Allgemeiner teil, Berlin, 1988. p. 42829R. Marino, R. Petrucci, Codice penale e leggi complementarii, Napoli, 2004.p.31; E. Foregger, E. Serini, Strafgesetzbuch, Wien, 1989. p.444BORISLAV PETROVIĆ PHD, AND DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - BASESFOR THE EXCLUSION OF THE CRIMINAL ACT IN CRIMINALLAW OF BOSNIA AND HERZGEGOVINA