als with the particular disability in question ortheir view <strong>of</strong> the burden that caring for such achild will place on them or their family; and4. cases where agencies charged with the protection<strong>of</strong> children or persons with disabilities havereason to believe that a disability, rather than theneed for and usefulness <strong>of</strong> treatment, was thedeterminative factor in the decision to denytreatment, and the agency declines to intervene,even though it would do so if the child in questiondid not have a disability.Part one <strong>of</strong> this chapter, therefore, examines thenature and extent <strong>of</strong> the equal protection andprocedural due process constitutional rights at stakein the types <strong>of</strong> denial <strong>of</strong> treatment cases raisedabove. Part two examines the interests and rights <strong>of</strong>parents as potential substantive limitations on therecognition and protection <strong>of</strong> such rights, and partthree discusses the ability and willingness <strong>of</strong> courtsto protect the rights <strong>of</strong> newborns denied treatmenton the basis <strong>of</strong> disability. The chapter concludeswith a discussion <strong>of</strong> whether or not there is a needfor Federal legislative, administrative, or judicialintervention on behalf <strong>of</strong> newborn children who aredenied treatment on the basis <strong>of</strong> disability.The Constitutional Rights <strong>of</strong> NewbornChildren with DisabilitiesThe constitutional right <strong>of</strong> newborn children todue process and equal protection <strong>of</strong> the law is notopen to question. Section 1 <strong>of</strong> the 14th amendmentprovides in relevant part that:All persons born or naturalized in the United States andsubject to the jurisdiction there<strong>of</strong>, are citizens <strong>of</strong> theUnited States and <strong>of</strong> the State wherein they reside. NoState shall make or enforce any law which shall abridgethe privileges or immunities <strong>of</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> the UnitedStates; nor shall any State deprive any person <strong>of</strong> life,liberty, or property, without due process <strong>of</strong> law; nor denyto any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection <strong>of</strong>the laws. 4As persons who are also citizens, persons withdisabilities, including newborn children, 5 are entitledto the same legal protection <strong>of</strong> their lives,physical integrity, and procedural due process rightsas infants, children, and adults without disabilities. 6Equal Protection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Law</strong>sThe legal standards governing discrimination onthe basis <strong>of</strong> handicap or disability are undergoingrapid development as developments in vocationalrehabilitation, biotechnology, and medicine influencechanges in public attitudes toward those withdisabilities. 7 Federal law requires, among otherthings, that any federally funded program or activitymust refrain from discriminating against an "otherwisequalified" individual "solely on the basis <strong>of</strong> hishandicap" 8 and that children with disabilities mustbe <strong>of</strong>fered equal educational opportunities. 9 Many4U.S. CONST, amend. XIV, § 1. Although this language appliesonly to the States, the Supreme Court has held that "[t]he federalsovereign, like the States, must govern impartially. The concept<strong>of</strong> equal justice under law is served by the Fifth Amendment'sguarantee <strong>of</strong> due process, as well as by the Equal ProtectionClause <strong>of</strong> the Fourteenth Amendment." Hampton v. Mow SunWong, 426 U.S. 88, 100 (1976). Accord, United States Dep't <strong>of</strong>Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528, 533, n. 5 (1973); Boiling v.Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499 (1954).5In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 13 (1967) ("[W]hatever may be theirprecise impact, neither the Fourteenth Amendment nor the Bill <strong>of</strong>Rights is for adults alone."). Accord Thompson v. Oklahoma, 108S.Ct. 2687 (1988) (death penalty for minors); Goss v. Lopez, 419U.S. 565 (1975) (procedural due process). The liberty interests <strong>of</strong>children are also protected, though, in some cases, to a lesserdegree than for adults. See, e.g., Hazelwood <strong>School</strong> Dist. v.Kuhlmeier, 108 S.Ct. 562 (1988); Tinker v. Des Moines <strong>School</strong>Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969); West Virginia Bd. <strong>of</strong> Educ. v.Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).6City <strong>of</strong> Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. 432(1985) [hereinafter Cleburne Living Center].7See, e.g., Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. 432 (1985)(constitutional standard for discrimination against the personswith disabilities in cases involving exclusionary zoning); ConsolidatedRail Corp. v. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624 (1984) (coverage <strong>of</strong>funded programs); Alexander v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287 (1985)(application <strong>of</strong> "disparate impact" theory as a matter <strong>of</strong> law orregulation); Smith v. Robinson, 468 U.S. 992 (1984) (relationship<strong>of</strong> the Education <strong>of</strong> the Handicapped Act, 20 U.S.C.A.§§ 1400-1485, (1982) [hereinafter cited as E.HA.] to section 504 <strong>of</strong>the Rehabilitation Act <strong>of</strong> 1973, 29 U.S.C.A. §794 (1982) and the14th amendment); Bd. <strong>of</strong> Educ. v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176 (1982)(extent <strong>of</strong> rights under E.H.A.); Southeastern Community Collegev. Davis, 442 U.S. 397 (1979) (limits on reach <strong>of</strong> section 504).See also, Americans with Disabilities Act <strong>of</strong> 1988, S. 2345, 100thCong., 2d Sess.8Section 504 <strong>of</strong> the Rehabilitation Act <strong>of</strong> 1973, 29 U.S.C.A.§794 (1988) provides, in relevant part:No otherwise qualified individual with handicaps. . .shall,solely by reason <strong>of</strong> his handicap, be excluded from theparticipation in, be denied the benefits <strong>of</strong>, or be subjected todiscrimination under any program or activity receivingFederal financial assistance. . . .See Consolidated Rail Corp. v. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624 (1984)(Federal funds need not be given with the "primary objective" <strong>of</strong>promoting employment to subject the recipient to the requirements<strong>of</strong> section 504). The definition <strong>of</strong> the term "handicappedindividual" is found in 29 U.S.C.A. §7O6(8)(B) (1988): "the term'individual with handicaps' means. . .any person who (i) has aphysical or mental impairment which substantially limits one ormore <strong>of</strong> such person's major life activities, (ii) has a record <strong>of</strong> suchan impairment, or (iii) is regarded as having such an impairment."94

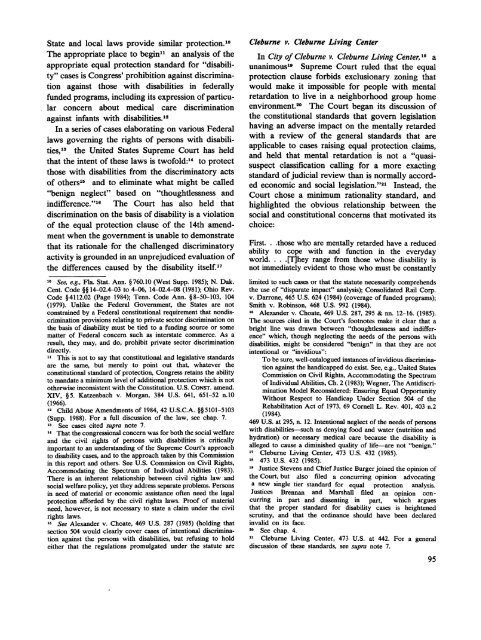

State and local laws provide similar protection. 10The appropriate place to begin 11 an analysis <strong>of</strong> theappropriate equal protection standard for "disability"cases is Congress' prohibition against discriminationagainst those with disabilities in federallyfunded programs, including its expression <strong>of</strong> particularconcern about medical care discriminationagainst infants with disabilities. 12In a series <strong>of</strong> cases elaborating on various Federallaws governing the rights <strong>of</strong> persons with disabilities,13 the United States Supreme Court has heldthat the intent <strong>of</strong> these laws is tw<strong>of</strong>old: 14 to protectthose with disabilities from the discriminatory acts<strong>of</strong> others 15 and to eliminate what might be called"benign neglect" based on "thoughtlessness andindifference." 16 The Court has also held thatdiscrimination on the basis <strong>of</strong> disability is a violation<strong>of</strong> the equal protection clause <strong>of</strong> the 14th amendmentwhen the government is unable to demonstratethat its rationale for the challenged discriminatoryactivity is grounded in an unprejudiced evaluation <strong>of</strong>the differences caused by the disability itself. 1710See, e.g., Fla. Stat. Ann. §760.10 (West Supp. 1985); N. Dak.Cent. Code §§ 14-02.4-03 to 4-06, 14-02.4-08 (1981); Ohio Rev.Code §4112.02 (Page 1984); Tenn. Code Ann. §8-50-103, 104(1979). Unlike the Federal Government, the States are notconstrained by a Federal constitutional requirement that nondiscriminationprovisions relating to private sector discrimination onthe basis <strong>of</strong> disability must be tied to a funding source or somematter <strong>of</strong> Federal concern such as interstate commerce. As aresult, they may, and do, prohibit private sector discriminationdirectly.11This is not to say that constitutional and legislative standardsare the same, but merely to point out that, whatever theconstitutional standard <strong>of</strong> protection, Congress retains the abilityto mandate a minimum level <strong>of</strong> additional protection which is nototherwise inconsistent with the Constitution. U.S. CONST, amend.XIV, §5. Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 651-52 n.10(1966).18Child Abuse Amendments <strong>of</strong> 1984, 42 U.S.C.A. §§5101-5103(Supp. 1988). For a full discussion <strong>of</strong> the law, see chap. 7.13See cases cited supra note 7.14That the congressional concern was for both the social welfareand the civil rights <strong>of</strong> persons with disabilities is criticallyimportant to an understanding <strong>of</strong> the Supreme Court's approachto disability cases, and to the approach taken by this Commissionin this report and others. See U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,Accommodating the Spectrum <strong>of</strong> Individual Abilities (1983).There is an inherent relationship between civil rights law andsocial welfare policy, yet they address separate problems. Personsin need <strong>of</strong> material or economic assistance <strong>of</strong>ten need the legalprotection afforded by the civil rights laws. Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> materialneed, however, is not necessary to state a claim under the civilrights laws.15See Alexander v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287 (1985) (holding thatsection 504 would clearly cover cases <strong>of</strong> intentional discriminationagainst the persons with disabilities, but refusing to holdeither that the regulations promulgated under the statute areCleburne v. Cleburne Living CenterIn City <strong>of</strong> Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, aunanimous 19 Supreme Court ruled that the equalprotection clause forbids exclusionary zoning thatwould make it impossible for people with mentalretardation to live in a neighborhood group homeenvironment. 20 The Court began its discussion <strong>of</strong>the constitutional standards that govern legislationhaving an adverse impact on the mentally retardedwith a review <strong>of</strong> the general standards that areapplicable to cases raising equal protection claims,and held that mental retardation is not a "quasisuspectclassification calling for a more exactingstandard <strong>of</strong> judicial review than is normally accordedeconomic and social legislation." 21 Instead, theCourt chose a minimum rationality standard, andhighlighted the obvious relationship between thesocial and constitutional concerns that motivated itschoice:First. . .those who are mentally retarded have a reducedability to cope with and function in the everydayworld. . . .[T]hey range from those whose disability isnot immediately evident to those who must be constantlylimited to such cases or that the statute necessarily comprehendsthe use <strong>of</strong> "disparate impact" analysis); Consolidated Rail Corp.v. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624 (1984) (coverage <strong>of</strong> funded programs);Smith v. Robinson, 468 U.S. 992 (1984).18Alexander v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287, 295 & nn. 12-16. (1985).The sources cited in the Court's footnotes make it clear that abright line was drawn between "thoughtlessness and indifference"which, though neglecting the needs <strong>of</strong> the persons withdisabilities, might be considered "benign" in that they are notintentional or "invidious":To be sure, well-catalogued instances <strong>of</strong> invidious discriminationagainst the handicapped do exist. See, e.g., United StatesCommission on Civil Rights, Accommodating the Spectrum<strong>of</strong> Individual Abilities, Ch. 2 (1983); Wegner, The AntidiscriminationModel Reconsidered: Ensuring Equal OpportunityWithout Respect to Handicap Under Section 504 <strong>of</strong> theRehabilitation Act <strong>of</strong> 1973, 69 Cornell L. Rev. 401, 403 n.2(1984).469 U.S. at 295, n. 12. Intentional neglect <strong>of</strong> the needs <strong>of</strong> personswith disabilities—such as denying food and water (nutrition andhydration) or necessary medical care because the disability isalleged to cause a diminished quality <strong>of</strong> life—are not "benign."» Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. 432 (1985).18473 U.S. 432 (1985).19Justice Stevens and Chief Justice Burger joined the opinion <strong>of</strong>the Court, but also filed a concurring opinion advocatinga new single tier standard for equal protection analysis.Justices Brennan and Marshall filed an opinion concurringin part and dissenting in part, which arguesthat the proper standard for disability cases is heightenedscrutiny, and that the ordinance should have been declaredinvalid on its face.20See chap. 4.21Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. at 442. For a generaldiscussion <strong>of</strong> these standards, see supra note 7.95

- Page 1 and 2:

MedicalDiscriminationAgainstChildre

- Page 3 and 4:

idments • Section 504 • Medical

- Page 5:

LETTER OF TRANSMITTALThe PresidentT

- Page 9 and 10:

CONTENTSExecutive Summary 11. Funda

- Page 11:

12. The Performance of the Federal

- Page 14 and 15:

• The role of economic considerat

- Page 16 and 17:

disabilities at the time that the c

- Page 19 and 20:

generated by health care personnel

- Page 21:

ing how they would obtain medical r

- Page 24 and 25:

The Commission sees several advanta

- Page 26 and 27:

acquiescence in the death or elimin

- Page 28 and 29:

Services of the Department of Healt

- Page 30 and 31:

Chapter 1Fundamental Rights: An Int

- Page 32 and 33:

Carlton Johnson was evaluated by a

- Page 34 and 35:

"that Mr. and Mrs. Doe, after havin

- Page 36 and 37:

American Coalition of Citizens with

- Page 38 and 39:

Chapter 2The Physician-Parent Relat

- Page 40 and 41:

In all but a few cases, the parents

- Page 42 and 43:

the family, and the family went alo

- Page 44 and 45:

Chapter 3The Role of Quality of Lif

- Page 47:

transition from education to employ

- Page 50 and 51:

tion programs can become productive

- Page 52 and 53:

unsuccessful efforts of a private a

- Page 54 and 55:

[S]ince I have been at Children's M

- Page 56 and 57: Another survey by Siperstein, Wolra

- Page 58 and 59: of life with a child who is disable

- Page 60 and 61: Chapter 4The Role of Economic Consi

- Page 62 and 63: ©TABLE 4.1Pediatricians' Responses

- Page 64 and 65: • The differences in average cost

- Page 66 and 67: FIGURE 4.1Comparative Costs of Inst

- Page 68 and 69: Chapter 5State LawWhat is the law g

- Page 70 and 71: Like all authority. . .parental aut

- Page 72 and 73: This decision, however, was promptl

- Page 74 and 75: No otherwise qualified handicapped

- Page 76 and 77: Bloomington's Infant Doe in April 1

- Page 78 and 79: ONONTABLE 6.1Physician's assessment

- Page 80 and 81: Essentially, HHS interpreted the su

- Page 82 and 83: Final 504 RuleHHS received nearly 1

- Page 84 and 85: lifesaving operations to close her

- Page 86 and 87: any further implementation of the F

- Page 88 and 89: handicapped infants might violate S

- Page 90 and 91: the provision does cover discrimina

- Page 92 and 93: of the infants. The review mechanis

- Page 94 and 95: Under the law, the Department of He

- Page 96 and 97: that "the phrase 'or holds the reas

- Page 98 and 99: allows an infant to be denied nutri

- Page 100 and 101: avoid the explicit standards set fo

- Page 102 and 103: (as opposed to the far) future, the

- Page 104 and 105: It was recognized, therefore, that

- Page 108 and 109: cared for. They are thus different,

- Page 110 and 111: medical advice. Given the magnitude

- Page 112 and 113: tions at all regarding the subject

- Page 114 and 115: strates that there is a grave dange

- Page 116 and 117: Disincentives to Whistle BlowingDen

- Page 118 and 119: Using a cumulative scaling procedur

- Page 120 and 121: Of that 300 we targeted, approximat

- Page 122 and 123: Conclusionphysicians set forth in t

- Page 124 and 125: taking place when a report of suspe

- Page 126 and 127: where the parents say "the child fe

- Page 128 and 129: Nevertheless, the organization oppo

- Page 130 and 131: Chapter 11The Role and Performance

- Page 132 and 133: a member of the American Academy of

- Page 134 and 135: possibilities that "will be most li

- Page 136 and 137: clearly indicate that the committee

- Page 138 and 139: Reviewing the first 30 months of th

- Page 140 and 141: Webster's defines "suspected" as "t

- Page 142 and 143: Chapter 12The Performance of the Fe

- Page 144 and 145: The baby's doctor, E. Laurence Hode

- Page 146 and 147: to achieve a reasonable life". . .w

- Page 148 and 149: an unmarried mother receiving welfa

- Page 150 and 151: can be sure all appropriate actions

- Page 152 and 153: inquiries to determine whether they

- Page 154 and 155: Chapter 13The Protection and Advoca

- Page 156 and 157:

authority to conduct retrospective

- Page 158 and 159:

facility that uses such a committee

- Page 160 and 161:

Chapter 14Findings and Recommendati

- Page 162 and 163:

as the coordination and development

- Page 164 and 165:

in the advisory process who is conc

- Page 166 and 167:

A Dissenting View on the Report Med

- Page 168 and 169:

arts) to depend upon knowledge of h

- Page 170 and 171:

Attachments to Statement of William

- Page 172 and 173:

medical facility. Considerations su

- Page 174 and 175:

Fund for the Improvement of Postsec

- Page 176 and 177:

eports such as Kopelman et al. demo

- Page 178 and 179:

Appendix 1EXPOSING OUR CHILDREN, EX

- Page 180 and 181:

abilities or functions, they are de

- Page 182 and 183:

My principal reason for objecting t

- Page 184 and 185:

I derive this hint from the many co

- Page 186 and 187:

moral distinction. A girl is a huma

- Page 188 and 189:

Appendix 2SURVEY OFSTATE BABY DOE P

- Page 190 and 191:

insure the immediate referral of po

- Page 192 and 193:

Hospital Liaisons Designated in Mos

- Page 194 and 195:

BABY DOE COMPARED WITH REGULAR CPS

- Page 196 and 197:

We also asked state CPS offices wha

- Page 198 and 199:

Limited information was available o

- Page 200 and 201:

one-quarter felt that baby doe case

- Page 202 and 203:

Appendix 3INFANT CARE REVIEW COMMIT

- Page 204 and 205:

and guidelines concerning the withh

- Page 206 and 207:

treated to assure the prompt ^repor

- Page 208 and 209:

3. Educating Staff and FamiliesThre

- Page 210 and 211:

One of the 10 ethics committees vis

- Page 212 and 213:

asphyxiation during the birth proce

- Page 214 and 215:

Prospective Review -- Each committe

- Page 216 and 217:

OBSERVATIONSThe inspection found th

- Page 218 and 219:

May 1, 1989Page 2The Commission adv

- Page 220 and 221:

Doe 1 admitted on the record of the

- Page 222 and 223:

tion is the basis for failure to tr

- Page 224:

her (much appreciated) vote for thi