The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>SRA</strong><br />

<strong>Symposium</strong><br />

“Enriching the art<br />

and science <strong>of</strong> research<br />

administration through<br />

scholarship and<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional inquiry.”<br />

Contributed Papers, Posters, and Future Proposals<br />

2005 <strong>SRA</strong> Annual Meeting<br />

Milwaukee, Wisconsin<br />

October 15 - 19, 2005<br />

Edward F. Gabriele and Valerie J. Ducker<br />

General Editors<br />

Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

© 2005

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book<br />

2005 © Copyright by the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators, International located at 1901 N.<br />

Moore Street, Arlington, VA 22209.<br />

All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written consent <strong>of</strong> the authors in<br />

prohibited. Authors have permission to re-publish or re-present their work ad libitum.

Dear Colleagues and Friends,<br />

October 1, 2005<br />

Welcome to the 2005 <strong>SRA</strong> International meeting in Milwaukee! And welcome to the 2005 <strong>SRA</strong><br />

<strong>Symposium</strong>. I grew up on the East Coast in the inner city. I first encountered the City <strong>of</strong> Milwaukee<br />

in undergraduate and graduate studies. Over the years, I became deeply enamored <strong>of</strong> the marvelously<br />

rich cross-cultural heritage <strong>of</strong> this city and the Fox River Valley. Over my student years, I<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten felt caught up in the cultural “swirl” between such diverse traits as Milwaukee’s stalwart German<br />

heritage combined with the deep and mysterious richness <strong>of</strong> the Native American communities<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wisconsin. This wonderful mix <strong>of</strong> cultures provides our 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> with a powerful<br />

mix <strong>of</strong> metaphors. Let me explain.<br />

Research administration is an executive pr<strong>of</strong>ession with a distinct scholarly and pr<strong>of</strong>essional body<br />

<strong>of</strong> knowledge. Today, our pr<strong>of</strong>ession is seeing swift new challenges and opportunities. Indeed we<br />

are on the march. <strong>The</strong> drumbeat <strong>of</strong> our march resonates with a stalwart strength so well characterized<br />

by the heritage <strong>of</strong> this proud city. Our drumbeat also resonates with the rich cross-cultural<br />

mix <strong>of</strong> this extraordinary region. Like the total heritage <strong>of</strong> the Milwaukee cultural geography,<br />

research administration has a rich and stalwart tradition that is today being stretched by new<br />

challenges and opportunities for research and research management. Let me suggest, then, that<br />

our coming to Milwaukee is a highly poetic moment in time for us to celebrate the 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong>.<br />

Here we cherish and advance our <strong>SRA</strong> <strong>Symposium</strong> Tradition <strong>of</strong> scholarly inquiry and the<br />

exploration <strong>of</strong> emerging needs and services for our investigators and institutions. <strong>The</strong> 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

mirrors in a marvelously “coincidental way” the diverse geography <strong>of</strong> research administration<br />

with the rich cultural heritage <strong>of</strong> our proud hosts in Milwaukee.<br />

In this wonderful city with its marvelous cross-cultural historical heritage, we bring our rich tradition<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Symposium</strong> scholarship for the advancement <strong>of</strong> our body <strong>of</strong> knowledge and the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> this pr<strong>of</strong>ession we call research administration. Exploring and adapting with strength and<br />

respect for the rich mystery <strong>of</strong> what we do, the 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> is dedicated this year as always<br />

to furthering what we do to assist those whose genius is itself dedicated to the progress <strong>of</strong> human<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> life. May our time together enrich and stretch us to do more and be more for those who<br />

rely upon our Tradition <strong>of</strong> Genius and Industry as research administrators.<br />

With warm personal regards,<br />

Dr. Edward F. Gabriele<br />

<strong>Symposium</strong> Program Director &<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Chair

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Poster Abstracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1<br />

Lisa M. Brown. Clinical Research Study Budgeting Trends . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

Jess Dalton. Does Granting Permission to Retain DNA Samples for Future Genetic<br />

Studies Identify A Biased Population? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Mary E. Dougherty. Modeling a Successful Cash/Resources Management System for<br />

Scientific Research Field Sites in Developing Countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

Carol Fedor. <strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> a Research Administration Program in Adverse Event Reporting . . . . . 6<br />

Peggy Fischer. Making the Case for an Effective Compliance Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

Gary Lee Frye. Creating a “Value Added” Center by Expanding the Development Office<br />

Role Within the Larger Community . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Gus Godoy. Partnership Between VA Research and Development and Non-Pr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

Corporations – Its Impact on Research and Improved Medical Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<br />

William S. Kirby. “Best Practices” in Electronic Research Administration for Small and<br />

Mid- Sized Institutions: Selected Phase I Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Bruce Linn. ERA Reporting: <strong>The</strong> Measures that Matter. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Bruce Linn. Effort Certification: <strong>The</strong> Time is Now. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

Joseph L. Malone. <strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Defense (DoD) - Global Emerging Infections<br />

System (GEIS) Program. A Case Study in Administering Research Projects<br />

that Build Public Health Epidemiological and Laboratory Capacity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13<br />

Joseph Augustine Menna. Toward an Alternative Basis for Mentoring: Whole<br />

Brain Learning as an Alternative Pedagogy for the Education <strong>of</strong> Research<br />

Administrators and Research Personnel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

Martha F. Nelson. Performance Evaluation Metrics for Research Administrators . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

Gayle Simon. San Diego State University’s Site Visit Program: A Model for Collaboration<br />

and Enhanced Ethical Practices in Human Research Protections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

Luc Simon. Benchmark IT! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Marie F. Smith. Making the Team Work: Being Part <strong>of</strong> a Collaborative Venture . . . . . . . . . . 18<br />

Sabrina L. Smith. Envisioning the Research Administration Structure in an<br />

Integrated Health Care System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

Cliff Studman. Research Capacity Building in Africa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20<br />

Renee J. Vaughan. Ethical Communication in Research Administration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Angela Willis. Perceptions <strong>of</strong> the Research Office . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Karen M. Wilson. A “Roadmap” to Re-organization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23<br />

Papers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

Chris Asmann-Finch. Contextual Difficulties in IRB Deliberations –<br />

Principlist vs. Narrativist Ethical Frameworks. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27<br />

Karolis Bauza. One On One Mentoring: A Case Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35<br />

William R. Belisle. External Resource Acquisition and Management:<br />

“ A Tool for MSI Research and Sponsored Programs Administrators” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44<br />

Paula Bistak. <strong>The</strong> Utility <strong>of</strong> Gender, Race, and Ethnicity Reporting in<br />

Clinical Trials as an Indicator <strong>of</strong> Distributive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

Stephen W. Brabbs. Creating A Community <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61<br />

Philip A. Cola. <strong>The</strong> Development, Implementation and Evaluation <strong>of</strong> a Prospective<br />

Research Monitoring Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66<br />

John J. Gillon. After A Day <strong>of</strong> Infamy, December 7, 2003—What Regulatory<br />

Ethics Have Become at the National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health by August 31, 2005 . . . . . . . . . . 77<br />

Mark Gorringe. Developing A Formal Quality Management System and Measuring<br />

Perceptions <strong>of</strong> Service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87<br />

Rene Hearns. Process <strong>of</strong> Legitimizing a Pr<strong>of</strong>ession: Research Administration . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

Mark Hochhauser. Informed Consent: Writing? Readability? Understanding? Deciding? . . . . 105<br />

Mark Hochhauser. Liabilities <strong>of</strong> “unreadable” consent forms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115<br />

Elizabeth Holmes. <strong>The</strong> Unconscious Expression <strong>of</strong> Ego Defenses:<br />

Increasing Self-Knowledge for the Research Administrator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123<br />

Hoyman. A Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the IRB Infrastructure at Comprehensive and Predominantly<br />

Undergraduate Institutions in the South: Project Initiation and 2005 Update . . . . . . . . 127<br />

Jose Jackson. Focusing on Development: Strategies for Strengthening Research at the<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Botswana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132<br />

William S. Kirby. “Best Practices” in Electronic Research Administration for<br />

Small and Mid Sized Institutions: Selected Phase I Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144<br />

Ed Mason. <strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> Development in a Research Administration Office . . . . . . . . . . . . 151<br />

Isaac N. Mazonde. Research Management in Southern African Higher<br />

Learning Institutions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161<br />

Stuart McKissock. European and Federal Funding Comparison:<br />

Ever thought about getting research funding from Europe?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Rebbecca A. Moen. Virgin Territory: <strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators in<br />

Mentoring Junior Faculty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186<br />

Elsa G. Nadler. Human Subjects Research and Protections: A Brief History. . . . . . . . . . . . 194<br />

Sandra M. Nordahl. Mentoring and Motivating: Bring Your Staff Along . . . . . . . . . . . . . 208<br />

Robert Porter. Helpful Gatekeepers: Positive Management <strong>of</strong> the Limited Submission Process . . 215<br />

Thomas J. Roberts. Perceptions <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators on the Value <strong>of</strong> Certification . . . . 221<br />

Debra S. Schaller-Demers. Why Do Ethical Scientists Make Unethical Decisions? . . . . . . . . 233<br />

Marie F. Smith. <strong>The</strong> Ups and Downs <strong>of</strong> Collaborative Ventures:<br />

A Case Study on Being a Collaborator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241<br />

<strong>The</strong>resa Ann Strakos. How to Develop a Centralized Pre-award Infrastructure Successfully Within<br />

a Climate Where the Number <strong>of</strong> Clinical Trials Sponsored by Pharmaceutical Industry Has<br />

Decreased Since 2001 – A Large Multi-Specialty Academic Medical Center Perspective. . . 248<br />

Cliff Studman. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Strategies for Building a Research Culture –<br />

an Empirical Case Study at an African University . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 258<br />

Michael Whitecar. Peer-to-Peer Discovery: Beyond Knowledge Management . . . . . . . . . . 269<br />

<strong>Symposium</strong> Future Proposals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275<br />

Jennifer Conway. Humanism in <strong>Medicine</strong>: A Case Study in Mentor/Trainee<br />

Responsibilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277<br />

Edward Gabriele. <strong>The</strong> Invisible Cartology <strong>of</strong> Culture: <strong>The</strong> Challenge <strong>of</strong> Cultural Paradigms in the<br />

Development <strong>of</strong> International Medical Research And Healthcare Policy . . . . . . . . . . . 278<br />

Cindy Kiel. FOIA and the FAR: Fear or Freedom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279<br />

Bruce Linn. Reporting for Electronic Research Administration: <strong>The</strong> Measures That Matter . . . 280<br />

David F. Steele. “Unwitting Human Subjects: Living in the Shadow <strong>of</strong> the Bomb in<br />

[town to be determined]” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

Poster Abstracts

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Lisa M. Brown, MBA<br />

Author Affiliation: Center for Clinical Research<br />

University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland<br />

Author Email: LisaM.Brown@uhhs.com<br />

Author Address: Center for Clinical Research<br />

University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland<br />

11100 Euclid Avenue, LKS 1400<br />

Cleveland, Ohio 44106-7061<br />

Secondary Authors: David K. Ehlert, Center for Clinical Research,<br />

University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland<br />

Philip A. Cola, M.A., Center for Clinical Research,<br />

University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland<br />

Title: Clinical Research Study Budgeting Trends<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

<strong>The</strong> Center for Clinical Research at University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland (UHC) provides legal and<br />

budget review, and administrative support, for over 360 clinical studies annually, which span<br />

twenty-four academic and clinical departments. Each study is governed by unique legal and fiscal<br />

terms. <strong>The</strong> budgets for these studies must not only reimburse for the fair market value <strong>of</strong> the<br />

medical services provided, but must also comply with numerous regulations designed to protect<br />

the interests <strong>of</strong> subjects enrolling in these studies.<br />

Many factors cause these budgets to differ. A review <strong>of</strong> 120 clinical research study agreements and<br />

budgets executed in 2004 was conducted across the various medical disciplines to understand<br />

where trends existed in clinical research budgets. <strong>The</strong>se budgets were reviewed to determine the<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> the differences in the per subject reimbursement: (i) by medical discipline; (ii) by the<br />

phase <strong>of</strong> the study drug/device development as determined by the FDA; (iii) <strong>of</strong> drug studies compared<br />

to the per subject reimbursement <strong>of</strong> device studies; and (iv) as a function <strong>of</strong> indirect rates<br />

provided by sponsors. <strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> this sample reveal trends in budgeting that provide useful<br />

information to research administrators during clinical research study budget negotiations.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 3

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Presenting Author: Jess Dalton, MSPH<br />

Author Affiliation: Obstetrics and Gynecology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Utah Division <strong>of</strong> Maternal-Fetal <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

Author Email: Jess.Dalton@hsc.utah.edu<br />

Author Address: Obstetrics and Gynecology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Utah Division <strong>of</strong> Maternal-Fetal <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

30 N. 1900 E., Suite 2B200<br />

Salt Lake City, Utah 84124, USA<br />

Primary Author: Kjersti Aagaard-Tillery, MD, PhD<br />

Obstetrics and Gynecology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Utah Division <strong>of</strong> Maternal-Fetal <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

Title: DOES GRANTING PERMISSION TO RETAIN DNA<br />

SAMPLES FOR FUTURE GENETIC STUDIES IDENTIFY<br />

A BIASED POPULATION?<br />

Abstract:<br />

From April 2000 to 2001, 5188 pregnant women were enrolled in a multicenter, prospective observational<br />

study. All participants provided a DNA sample to ascertain the estimated rate <strong>of</strong> adverse<br />

pregnancy outcomes. Enrolled women were asked if their samples could be used in a non-identifiable<br />

fashion for future genetic studies without their permission, whether permission must be<br />

obtained prior to future use, or whether their samples were to be destroyed following index study.<br />

Of 5188 women enrolled, 5003 women indicated a preference. Overall, 72.5% gave unrestricted<br />

permission, 7.4% desired to provide authorization for future analyses, and 20.1% requested that<br />

samples be destroyed after primary analysis. Univariate analysis revealed that African-American<br />

women chose to discard samples more <strong>of</strong>ten than Caucasian/Jewish women (19.9 vs. 11.6%,<br />

p

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Mary E. Dougherty-Program Coordinator<br />

Author Affiliation: Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>/Department <strong>of</strong> Infectious Disease<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Alabama at Birmingham<br />

Author Email: mdougher@uab.edu<br />

Author Address: Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Alabama at Birmingham<br />

908 20th Street South<br />

CCB 328 B<br />

Birmingham, Alabama 35294 USA<br />

Secondary Authors: Susan Allen, MD, MPH Emory University, Rollins School <strong>of</strong> Public Health.<br />

Third Authors: Rwanda/Zambia HIV Research Group-Zambia Emory HIV Research Project<br />

(ZEHRP Lusaka, Zambia) and Project San Francisco (PSF Kigali, Rwanda)<br />

Title: Modeling a Successful cash/resources management system for<br />

scientific research field sites in developing countries.<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

In this poster we will detail the cash/resources management system utilized by scientific research<br />

field sites in Kigali, Rwanda (1984), Lusaka, Zambia (1994), Ndola and Kitwe, Zambia (2004).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se field sites and this system were established and or developed by Susan A. Allen, MD, MPH<br />

<strong>of</strong> Emory University/Rollins School <strong>of</strong> Public Health. <strong>The</strong> method revolves around the use <strong>of</strong> a rotating<br />

Imprest (petty) cash fund. Utilizing this fund effectively allows for many benefits including<br />

smooth transfer <strong>of</strong> funds from the US to the project field site. It also allows for careful documentation<br />

and review <strong>of</strong> expenditures, as well as accountability and transparency for both the sponsoring<br />

agency and the funded institution. Our approach also guarantees maximum security <strong>of</strong> funds<br />

that are available for use in country by the project field sites. Through the past 18 years, use <strong>of</strong> this<br />

system has demonstrated the ability to safeguard resources <strong>of</strong> the project in <strong>of</strong>ten unstable political<br />

and or economic environments. <strong>The</strong> design <strong>of</strong> this system is both flexible and transparent making<br />

it ideal for use by researchers and public health <strong>of</strong>ficials in many parts <strong>of</strong> the world.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 5

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Carol Fedor, ND, Clinical Research Manager<br />

Author Affiliation: <strong>The</strong> Center for Clinical Research, UHC<br />

Author Email: carol.fedor@uhhs.com<br />

Author Address: <strong>The</strong> Center for Clinical Research<br />

University Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Cleveland (UHC)<br />

11100 Euclid Avenue<br />

Cleveland, OH 44024, US<br />

Secondary Authors: Philip Cola, MA, Director<br />

& Louise Haffke, MPH, Research Compliance Specialist<br />

<strong>The</strong> Center for Clinical Research, UHC<br />

William Dahms, MD, Vice-Chair<br />

UHC Institutional Review Board<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> a Research Administration Program in<br />

Adverse Event Reporting<br />

Abstract:<br />

<strong>The</strong> reporting, analysis, and management <strong>of</strong> adverse events (AEs) provide an ongoing assessment<br />

<strong>of</strong> risk in the context <strong>of</strong> a clinical trial and ensures the protection <strong>of</strong> human research participant<br />

safety and informed consent. Effective and efficient review <strong>of</strong> adverse events has been a longstanding<br />

challenge for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Research Administration programs<br />

especially as protocols and ethical/legal issues become more complex. Furthermore, AE reporting<br />

is governed by many different regulations and sources, with inconsistencies in standards and<br />

requirements. Reporting standards for AEs were adopted when single-center trials were the norm.<br />

With the increased prevalence <strong>of</strong> multi-center trials, IRBs are now inundated with AE reports with<br />

some IRBs receiving more than 10,000 reports annually. This poster will review the current issues<br />

in AE reporting and the challenges faced by a research administration program in the process <strong>of</strong><br />

re-evaluating current policies and procedures and implementing a significantly revised reporting<br />

policy. <strong>The</strong> implementation plan and educational strategies used with the investigators and<br />

research staff will be described. Preliminary outcome data will be presented to evaluate the policy<br />

revisions and to take into consideration the concepts <strong>of</strong> “quality <strong>of</strong> analysis” versus “quantity <strong>of</strong><br />

reporting”.<br />

6 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Peggy Fischer, PhD<br />

Author Affiliation: Associate Inspector General for Investigations<br />

National Science Foundation Office <strong>of</strong> Inspector General<br />

Author Email: pfischer@nsf.gov<br />

Author Address: Office <strong>of</strong> Inspector General<br />

National Science Foundation<br />

4201 Wilson Blvd., Suite II-705<br />

Arlington, VA 22230 USA<br />

Secondary Authors: William J. Kilgallin<br />

Head, Investigative Legal and Outreach<br />

National Science Foundation Office <strong>of</strong> Inspector General<br />

Title: Making the Case for an Effective Compliance Program<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

<strong>The</strong> poster communicates points <strong>of</strong> advocacy for use in making a case to university management<br />

for funds and personnel necessary for an effective compliance program. <strong>The</strong> poster illustrates both<br />

the need for, and value <strong>of</strong>, such a program. It asks and answers the questions: “How can I argue for<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> an effective compliance program when competing for money and staff? What do I say<br />

to get management’s attention when other issues are begging for attention? How do I keep ethics and<br />

integrity in the spotlight?” <strong>The</strong> poster summarizes the major developments that have changed the<br />

research environment in this area, namely, Enron, Sarbanes-Oxely, SAS 99, Sentencing Guidelines<br />

for Organizational Offenders, June 05 CoGR Guide, etc. It presents a visual depiction <strong>of</strong> the true<br />

costs for poor compliance (money and imposed compliance plans, settlements, qui tam suits, etc.).<br />

It displays the elements <strong>of</strong> an effective compliance program. It presents an illustrative university<br />

“heat map” that identifies contracts and grants management as the highest risk and highest impact<br />

activity. And it sets out the two ways to get to compliance, namely imposed or adopted and the<br />

costs/benefits <strong>of</strong> both routes.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 7

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Dr. Gary Lee Frye<br />

Author Affiliation: Director <strong>of</strong> Development and Grants<br />

Lubbock-Cooper Independent School District<br />

Author Email: glfrye@lcisd.net<br />

Author Address: Central Office<br />

Lubbock-Cooper ISD<br />

16302 Loop 493<br />

Lubbock, Texas 79423-7805<br />

Title: Creating a “Value Added” Center by Expanding the Development Office<br />

Role within the Larger Community<br />

Abstract:<br />

This poster shows how Lubbock-Cooper ISD’s Development Office expanded its role in the community<br />

to provide value added services. <strong>The</strong> Development Office developed a funded 21st Century<br />

Community Learning Center grant which was a consortium <strong>of</strong> five area school districts. To<br />

meet a grant requirement <strong>of</strong> having a plan to continue the program beyond this grant’s funding<br />

the Llano Estacado Rural Communities Foundation was created. <strong>The</strong> foundation’s by-laws expanded<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> the grant writing and other fund raising activities into the area <strong>of</strong> “improving<br />

the quality <strong>of</strong> life” for all community stakeholders in the five communities. Through the creation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the foundation the philanthropic activities in these communities has been greatly increased by<br />

developing grants for several agencies which before this did not see their missions as overlapping.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se activities are leading to the development <strong>of</strong> a community/regional-wide mind-set <strong>of</strong> looking<br />

meeting the needs <strong>of</strong> community stakeholders by blending the activities <strong>of</strong> various agencies<br />

and service providers. This blending is allowing resources from various agencies to be used to<br />

meet community needs and develop stronger multi-agency consortiums which are now working<br />

together to submit grant proposals.<br />

8 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administration International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Gus Godoy, CRA<br />

Author Affiliation: Executive Director and Administrative Officer for R & D<br />

South Florida VA Foundation for Research and Education<br />

Author Email: Gustavo.godoy@med.va.gov<br />

Author Address: Executive Director and Administrative Officer for R & D<br />

South Florida VA Foundation for Research and Education<br />

Miami VA Medical Center<br />

1201 N. W. 16th Street, room 2A102,<br />

Miami, FL, 33125, USA<br />

Title: “Partnership between VA Research and Development and<br />

Non-Pr<strong>of</strong>it Corporations – Its Impact on Research and Improved<br />

Medical Care”.<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

<strong>The</strong> enactment by Congress <strong>of</strong> Public Law 85-857 in 1958 established Research and Development<br />

as an <strong>of</strong>ficial component <strong>of</strong> the health care mission <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Veterans Affairs (VA). In<br />

recent years, in order to sustain their research programs in the face <strong>of</strong> shrinking VA support, VA<br />

research scientists have increasingly sought support from extramural sources, including other Federal<br />

agencies, research foundations and industrial companies. This extramural support has steadily<br />

increased over the years and in FY 2003 it was approximately $185 million, nearly one-half <strong>of</strong> the<br />

total current support for VA investigators ($406 million). To regulate the administration <strong>of</strong> these<br />

non- federally appropriated funds, Congress enacted Public Law 100-322, which allows the establishment<br />

<strong>of</strong> VA non-pr<strong>of</strong>it research corporations and governs how they shall function. <strong>The</strong> existence<br />

<strong>of</strong> these foundations has provided a greater degree <strong>of</strong> flexibility in administration <strong>of</strong> funds,<br />

purchasing, and personnel actions, compared to federally operated programs, and it has proven<br />

to be a major boon to VA medical research. Consequently, research foundations have contributed<br />

substantially to the VA researchers’ constant seeking <strong>of</strong> new ways to prevent, treat and cure disease<br />

for veterans and Americans.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 9

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: William S. Kirby<br />

Author Affiliation: Principal Investigator<br />

Research and Management Systems<br />

Author Email: wkirby@crosslink.net<br />

Author Address: P.O. Box 717<br />

Heathsville, VA 22473<br />

Secondary Authors: Michael R. Dingerson<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Educational Leadership and Counseling<br />

Darden <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> Education<br />

Old Dominion University<br />

Norfolk, Virginia 23529-0157<br />

Title: “Best Practices” in Electronic Research Administration for Small<br />

and Mid Sized Institutions: Selected Phase I Results<br />

Abstract:<br />

As a part <strong>of</strong> an NIH SBIR award to Research and Management Systems, the authors conducted a<br />

review <strong>of</strong> three universities recognized as leaders in eRA. <strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> the study is to develop<br />

an understanding <strong>of</strong> the leading institutions’ approach to eRA planning, systems and s<strong>of</strong>tware,<br />

staffing and other practices used in moving their eRA efforts forward. <strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> the research is<br />

to describe and characterize common principles and conditions that may contribute to success for<br />

these institutions. In the second phase <strong>of</strong> this study, the authors reviewed several small and mid<br />

sized institutions that have completed or are in the process <strong>of</strong> implementing eRA systems to identify<br />

“lessons learned” from those implementations. By examining what happens in small and mid<br />

sized institutions, one can begin to describe 1) the extent to which the principles and practices<br />

identified in leading institutions are applicable in a small and mid sized institution setting, and 2)<br />

implications for government-wide plans for universal electronic submission.<br />

10 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Bruce Linn<br />

Author Affiliation: Director Database Development<br />

ERA S<strong>of</strong>tware Systems, Inc.<br />

Author Email: blinn@eras<strong>of</strong>twaresystems.com<br />

Author Address: ERA S<strong>of</strong>tware Systems, Inc<br />

357 Castro Street, #6<br />

Mountain View, CA 94041 USA<br />

Title: ERA Reporting: <strong>The</strong> Measures that Matter<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

<strong>The</strong> automation <strong>of</strong> grant management via Electronic Research Administration (ERA) <strong>of</strong>fers clear<br />

opportunities for improved process efficiency, accountability, and integrity. That said, the most<br />

exciting benefits <strong>of</strong> ERA may well be the potential <strong>of</strong> placing a wealth <strong>of</strong> meaningful information<br />

within easy reach <strong>of</strong> key users – in the form <strong>of</strong> a dynamic and accessible ERA reporting system.<br />

This poster is intended to provide a graphical introduction to the essential elements <strong>of</strong> electronic<br />

reporting systems for funded research. Two topics are addressed: first, what are the key user<br />

requirements, and expected benefits, <strong>of</strong> ERA reporting. Second, what are the critical business<br />

analyses that can be answered most effectively with ERA reporting. <strong>The</strong> poster will use several real<br />

world example <strong>of</strong> ERA reports which highlight effective analysis in the areas <strong>of</strong> funding forecasts,<br />

cost share and salary cap, certification <strong>of</strong> time and effort, and managing award expenditures.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 11

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Bruce Linn<br />

Author Affiliation: Director Database Development<br />

ERA S<strong>of</strong>tware Systems, Inc.<br />

Author Email: blinn@eras<strong>of</strong>twaresystems.com<br />

Author Address: ERA S<strong>of</strong>tware Systems, Inc<br />

357 Castro Street, #6<br />

Mountain View, CA 94041 USA<br />

Title: Effort Certification: <strong>The</strong> Time is Now<br />

Abstract:<br />

Effort certification is a hot topic within sponsored research institutions, and with good reason.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Office <strong>of</strong> the Inspector General has emphasized effort reporting in their 2005 Work Plan for<br />

future audits. Many institutions are currently at risk – unable to reliably collect, certify, and document<br />

the award related effort expended by their own research personnel. This poster will provide<br />

a graphical ‘checklist’ designed to introduce the key concepts and critical requirements <strong>of</strong> effective<br />

effort certification and reporting for electronic research administration. Key problem areas<br />

in effort reporting will be identified, and best practices for effort certification and reporting will<br />

be introduced. A ‘typical’ electronic effort reporting system that meets audit requirements will be<br />

graphically illustrated and described.<br />

12 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: CAPT Joseph L. Malone, MC, USN, MD<br />

Author Affiliation: Director, Department <strong>of</strong> Defense -<br />

Global Emerging Infections System (DoD-GEIS)<br />

Author Email: joseph.malone@na.amedd,army.mil<br />

Author Address: Walter Reed Army Institute <strong>of</strong> Research (WRAIR)/<br />

Naval Medical Research Center (NMRC)<br />

503 Robert Grant Avenue,<br />

Silver Spring, MD 20910-7500<br />

Secondary Authors: Mr. Stephen Gubenia (DoD-GEIS, WRAIR)<br />

Ms. Jennifer Rubenstein (DoD-GEIS, WRAIR)<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Defense (DoD) - Global Emerging Infections System (GEIS) Program.<br />

A Case Study in Administering Research Projects that Build Public Health Epidemiological and<br />

Laboratory Capacity<br />

Abstract: <strong>The</strong> complexity <strong>of</strong> conducting medical protocols involving public health surveillance in<br />

developing countries involving research laboratories within the United States poses many challenges<br />

to research administrators. DoD-GEIS identifies and contains infectious threats worldwide<br />

especially at five DoD overseas medical research laboratories through cooperative arrangements<br />

with CDC, with WHO, and with the governments <strong>of</strong> foreign countries. DoD-GEIS also promotes<br />

outbreak response preparation within the United States by supporting public health laboratory<br />

and epidemiology investigation functions throughout the military medical research laboratory<br />

system and military health system that provides clinical care for the 8,595,000 military medical<br />

beneficiaries worldwide. Although some DoD-GEIS projects such as outbreak investigations<br />

are typically considered public health practice rather than medical research as defined by federal<br />

regulations, many DoD-GEIS activities are administrated through cooperative arrangements and<br />

with protocols that are typical for public health surveillance projects, and that involve pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

training and public health capacity building. This poster will detail the unique mission and administrative<br />

challenges <strong>of</strong> the program. <strong>The</strong> poster will present for research administrators the<br />

complexities <strong>of</strong> management and oversight for a large, multinational medical and research-related<br />

program <strong>of</strong> inquiry and service.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 13

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Very Reverend Joseph Augustine Menna, AIHM<br />

Author Affiliation: Belmont Charter School<br />

Author Email: JMennaAIHM@aol.com<br />

Author Address: 340 Media Station Road, A302<br />

Media, PA 19063<br />

Title: Toward an Alternative Basis for Mentoring: Whole Brain Learning as an<br />

Alternative Pedagogy for the Education <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators and<br />

Research Personnel<br />

Abstract:<br />

Research Administration has enjoyed a 60 year history <strong>of</strong> service to scientific personnel. It has<br />

grown far beyond the minimal standard <strong>of</strong> regulatory compliance. However, research administrators<br />

and investigators too <strong>of</strong>ten still do not understand the far reaching importance <strong>of</strong> proactive<br />

research management standards for strategic planning and development <strong>of</strong> research institutions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> antipathies between research administrators and investigators are <strong>of</strong>ten the result <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong><br />

understanding or the lack <strong>of</strong> a positive panorama <strong>of</strong> management possibilities. Whole brain learning,<br />

as typified in the 4-MAT pedagogy, provides an alternative paradigm upon which to build<br />

mentoring and education programs and curricula in research management for administrators and<br />

investigators. <strong>The</strong> approach <strong>of</strong>fers an enthusiastic forum in which to bring together administrators<br />

and researchers as positive partners in the processes <strong>of</strong> research management. Whole brain<br />

learning research, as typified in the 4-MAT pedagogy, utilizes the latest in psychological, physiological,<br />

and developmental research to map how we as human beings, intake, process, and utilize<br />

information. <strong>The</strong>se current theories in education and learning styles have been implemented from<br />

classroom education to Fortune 500 company management and training sessions and they hold<br />

impressive possibilities for research administrators and investigators.<br />

14 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Martha F. Nelson, RN MS MPA<br />

Author Affiliation: Office <strong>of</strong> Clinical Trials<br />

United Health Services Hospitals, Inc.<br />

Author Email: Martha_Nelson@uhs.org<br />

Author Address: 33-57 Harrison Street<br />

Johnson City, NY 13790<br />

USA<br />

Secondary Authors: none<br />

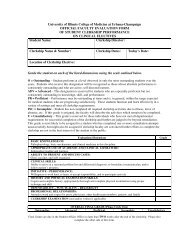

Title: Performance Evaluation Metrics for Research Administrators<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

With current brouhaha over lapses in accountability and responsibility among industry leaders,<br />

performance management is becoming a strategic imperative for organizations. Some organizations<br />

have led by developing clear policies, firm controls and commitment to excellence. In developing<br />

that culture, an organization needs to define specific targets using measurable tools, allocate<br />

resources, and connect processes with its core values and principles. <strong>The</strong> Campaign for Excellence<br />

(C4E) celebrating its third year at UHSH identified six key pillars that affect overall performance<br />

<strong>of</strong> employees. Using the pillars People, Service, Quality, Finance, Growth, Community, the author<br />

designed a Leader Evaluation Metrics for performance measurement. Each pillar carries a<br />

weighted value. Goals with concurrent results are scaled 1-5, (1 Poor -5 Excellent). By multiplying<br />

these factors, one gets an average score for that area. Add up scores for each pillar, an overall<br />

performance score is reached where 5.0 is the highest. Devised for self-evaluation, the process is<br />

reported quarterly to senior management. Taking this deliberative approach, the metrics’ form<br />

becomes a formal mechanism to honestly document and report with integrity one’s accomplishments.<br />

Moreover, it presents a locus to reward and recognize achievement which creates an incentive<br />

that enables one to seek exemplary performance.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 15

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Gayle Simon, M.P.H.<br />

Author Affiliation: Graduate & Research Affairs<br />

Institution: San Diego State University<br />

Author Email: gsimon@projects.sdsu.edu<br />

Author Address: Graduate & Research Affairs, Division <strong>of</strong> Research Administration<br />

5500 Campanile Drive, MC 1643<br />

San Diego State University<br />

San Diego, CA 92182-1643<br />

Title: San Diego State University’s Site Visit Program: A Model for<br />

Collaboration and Enhanced Ethical Practices in Human Research<br />

Protections<br />

Abstract:<br />

Efforts to enhance protection <strong>of</strong> human research subjects are a priority among research institutions<br />

with educational initiatives mandated and quality improvement emphasized. Problems<br />

and controversies unique to social/behavioral sciences research also require attention specific to<br />

education and oversight. One initiative developed by SDSU to improve oversight <strong>of</strong> responsible<br />

research practices involved conducting proactive ‘not for cause’ site visits as part <strong>of</strong> its continuing<br />

review program for human subject’s protections. While site monitoring may be an expected<br />

activity within the biomedical community, this aspect <strong>of</strong> continuing review was novel to social and<br />

behavioral sciences investigators. This poster describes the process used to develop and implement<br />

a Site Visit Program at SDSU. <strong>The</strong> program objectives were to: 1- create an environment where<br />

on-site monitoring is accepted/valued; 2- enhance IRB awareness <strong>of</strong> practical issues from the<br />

investigator’s perspective; 3- promote communication between researchers and the IRB; and, 4-<br />

increase opportunities for training <strong>of</strong> ethical/responsible research practices. Steps taken to initiate<br />

development required careful planning and engagement <strong>of</strong> the research community in the process.<br />

Methods involved conducting interviews and focus groups with investigators, drafting procedures,<br />

pilot testing and implementation. <strong>The</strong> program is now operational and a valued part <strong>of</strong> SDSU’s<br />

human research protection program.<br />

16 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Luc Simon, Ph.D.<br />

Author Affiliation: Planning and Institutional Research Office<br />

Université Laval<br />

Author Email: Luc.Simon@vrex.ulaval.ca<br />

Author Address: BPEI<br />

Université Laval<br />

1556 Education bldg<br />

Quebec, Qc, G1K 7P4 Canada<br />

Secondary Author: Richard Massé, M. Sc.<br />

Planning and Institutional Research Office<br />

Université Laval<br />

Title: Benchmark IT!<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

A tool to facilitate the organization and exchange <strong>of</strong> benchmark data amongst institutions has<br />

been developed. <strong>The</strong> secretariat <strong>of</strong> the Canadian G10-DE, a data exchange consortium linking the<br />

institutional research <strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> the 10 most research intensive Canadian universities has recently<br />

begun using it. Rapid deployment in each <strong>of</strong> the consortium universities is planned. <strong>The</strong> functionality<br />

<strong>of</strong> this information system will be presented, as well as the potential impact <strong>of</strong> its adoption by<br />

other institutions.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 17

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Ms. Marie F. Smith, CRA<br />

Author Affiliation: Grants Office, Institute <strong>of</strong> Ecosystem Studies<br />

Author Email: smithm@ecostudies.org<br />

Author Address: Institute <strong>of</strong> Ecosystem Studies<br />

PO Box AB<br />

65 Sharon Turnpike<br />

Millbrook, NY 12545, USA<br />

Title: Making the Team Work: Being Part <strong>of</strong> a Collaborative Venture<br />

Abstract:<br />

Successful scientists work in teams, with their productivity relying on effective teamwork among<br />

collaborators. When everything goes well, collaborations result in higher quality research than<br />

could have been accomplished by scientists working alone (Kotok, 2004). Multi-organizational,<br />

multi-disciplinary research projects are on the rise. Research Administrators are partners with<br />

Research Investigators in collaborative ventures. Research Administrators seek to facilitate collaborative<br />

ventures while protecting the interests <strong>of</strong> the institution and the institutional research<br />

investigator. We must take care to facilitate not impede the collaborative process by providing a<br />

helpful and supportive framework that balances the needs <strong>of</strong> the institution, the investigator and<br />

the funding agency.<br />

18 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Assistant Vice President, Sabrina L. Smith, MHA, CRA<br />

Author Affiliation: Office <strong>of</strong> Contracts and Grants Management<br />

MedStar Research Institute<br />

Author Email: Sabrina.L.Smith@MedStar.net<br />

Author Address: Office <strong>of</strong> Contracts and Grants Management<br />

MedStar Research Institute<br />

6495 New Hampshire Avenue, Suite 201<br />

Hyattsville, Maryland 20783 USA<br />

Secondary Authors: Marsha A. Allen, MA<br />

MedStar Research Institute<br />

Title: Envisioning the Research Administration Structure in an<br />

Integrated Health Care System<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

This poster is a descriptive analysis <strong>of</strong> MedStar Research Institute’s research administration (RA)<br />

structure and the provision <strong>of</strong> RA services to the MedStar Health system. MedStar Research Institute<br />

is a stand alone subsidiary <strong>of</strong> the larger system comprised <strong>of</strong> five tertiary care hospitals, two<br />

sub-acute hospitals and other affiliates. <strong>The</strong> provision and structure <strong>of</strong> the RA services to each site<br />

is impacted by the disparate geographic sites, differing organizational cultures, expectations, and<br />

varying levels <strong>of</strong> research acumen <strong>of</strong> the staff. Moreover, the information and financial systems at<br />

the sites are designed to capture patient level data and not geared toward research administration<br />

activities. <strong>The</strong> administrative services core has adapted to these challenges by developing working<br />

relationships with the hospital staff and the central business <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> the system to devise internal<br />

modifications and procedures that can be uniformly applied across the system. This helps to facilitate<br />

the research so that it appears to be seamless to the principal investigators. As the research<br />

enterprise continues to expand, future administrative services will need to be based on effective<br />

use <strong>of</strong> information technology, on-going grass root training <strong>of</strong> research and non-research staff,<br />

and a shared vision <strong>of</strong> research.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 19

Poster Abstracts<br />

Contributed Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee WI<br />

16-19 October 2005<br />

Principal Author: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Cliff Studman, PhD, Dip Ed, BSc.<br />

Affiliation: Pie Squared Pty<br />

Author Email: Studman@Botsnet.bw<br />

Author Address: Pie Squared Pty<br />

Box 45371 Riverwalk<br />

Gaborone, Botswana<br />

Title: Research Capacity Building in Africa<br />

Abstract<br />

In recent years there has been a significant increase in interest in African Studies. As a result<br />

research interest in the continent has grown, and with it the desire to collaborate with researchers<br />

within Africa, particularly on projects in health, or environmental and social science. However<br />

an analysis <strong>of</strong> data demonstrates that the continent itself lags behind the rest <strong>of</strong> the world<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> all measurable outputs. Internally there is a desire to change this situation, but there<br />

are constraints, including resources, staff retention, and research management expertise. On the<br />

other hand in most countries the continent now has significant numbers <strong>of</strong> staff in Universities<br />

trained to the level <strong>of</strong> PhD. Research managers should be aware <strong>of</strong> the need for sensitivity and<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> the situation in the potential host country when researchers propose projects in<br />

Africa. Based on specific examples <strong>of</strong> attempts at collaboration and capacity building, this poster<br />

will present some do’s and don’ts for potential researchers wishing to collaborate with African colleagues,<br />

including an African view <strong>of</strong> how collaborations should work. It also indicates the importance<br />

and potential <strong>of</strong> research management as a significant component in facilitating research<br />

capacity building.<br />

20 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Contributed Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Renee J. Vaughan, M.Div., M.A., CRA, RCC<br />

Director, Research Communication and Compliance<br />

Author Affiliation: Department <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences<br />

Duke University Medical Center<br />

Author Email: vaugh008@mc.duke.edu<br />

Author Address: Research Communication and Compliance Program<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences<br />

Duke University Medical Center<br />

2218 B-2 Elder St., Suite 119, Box 3257<br />

Durham, NC 27710, USA<br />

Secondary Authors: None<br />

Title: Ethical Communication in Research Administration<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

Research administration as a pr<strong>of</strong>ession necessitates the utilization <strong>of</strong> communication principles<br />

and strategies for successful interaction with stakeholders in a systemized approach to managing<br />

sponsored projects and regulatory compliance. Communication theories are inextricably linked to<br />

ethical reasoning through common principles <strong>of</strong> truth and honesty, trust and relationships, reputation<br />

and integrity, conduct and justice. Research Administrators through their relationships and<br />

values engage in communication in order to establish common agreements, policy and regulations.<br />

Further, ethical communication processes in the building <strong>of</strong> knowledge networks and risk reduction<br />

facilitate compliance. This poster will highlight the integrated framework <strong>of</strong> communication,<br />

ethics and compliance in research administration. It will detail a communication ethics mapping<br />

technique as a strategy to impact myriad issues encountered by the research administrator.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 21

Poster Abstracts<br />

Poster Abstract<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators International<br />

Milwaukee, WI<br />

October 16-19, 2005<br />

Principal Author: Ms. Angela Willis, MPA<br />

Author Affiliation: Office <strong>of</strong> Research and Sponsored Programs<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Arkansas at Little Rock<br />

Author Email: aewillis@ualr.edu<br />

Author Address: Office <strong>of</strong> Research and Sponsored Programs<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Arkansas at Little Rock<br />

2801 S. University Ave.<br />

Little Rock, AR 72204-1099<br />

Title: Perceptions <strong>of</strong> the Research Office<br />

Abstract:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Office <strong>of</strong> Research and Sponsored Programs (ORSP) at the University <strong>of</strong> Arkansas at Little<br />

Rock (UALR) was concerned with how its faculty and pr<strong>of</strong>essional staff perceived the <strong>of</strong>fice. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>fice wanted to determine the level <strong>of</strong> satisfaction <strong>of</strong> the services it provides; determine which<br />

services researchers appreciate and which need to be improved; and determine what factors effect<br />

faculty and pr<strong>of</strong>essional staff who have not sought funding within the past four years. <strong>The</strong> surveys,<br />

adapted Eastern Michigan University, went to A) only for those who have submitted proposals<br />

and have been funded in the past four years; B) only for those who have submitted proposals,<br />

but have not been funded in the past four years; C) only for those faculty who have not requested<br />

external funding in four years or more, or those faculty who have never requested external funding;<br />

D) Only for those staff persons who manage grants and contracts received by the university.<br />

Four hundred ninety-one surveys were distributed to all four groups, and a total <strong>of</strong> 71 surveys<br />

were received. This poster will present the surveys used and present the findings from the surveys<br />

received by group. Note: <strong>The</strong> effort cited here was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board that<br />

determined that it was exempt from regulations under 45 CFR 46.101. <strong>The</strong> poster will include this<br />

information and will also include the <strong>of</strong>ficial protocol number.<br />

22 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Poster Abstract<br />

Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Research Administrators<br />

Milwaukee WI<br />

16-19 October 2005<br />

Principal Author: Karen M. Wilson, Associate Director for Administration & Facilities<br />

Author Affiliation: Association <strong>of</strong> Universities for Research in Astronomy<br />

National Optical Astronomy Observatory<br />

Author Email: kwilson@noao.edu<br />

Author Address: AURA/NOAO<br />

950 N. Cherry Ave<br />

Tucson AZ 8572<br />

Title: A “ROADMAP” TO RE-ORGANIZATION<br />

Abstract:<br />

Poster Abstracts<br />

Senior Research Administrators are continually faced with the challenge <strong>of</strong> reorganizing operations.<br />

Whether it is due to obtaining a new position in their existing organization or another<br />

institutions, project management, overall institutional restructuring, budget pressures or mission<br />

changes there are common principals, practices and new opportunities and trends to guide our<br />

senior administrators to success. Developing a master plan prior to implementation <strong>of</strong> reorganization<br />

is the key. Knowing what to consider, review and use, and discard is the success factor.<br />

Focusing on making sure the right team, service and operational needs are met is a must. Formal<br />

education is this area is limited and accumulated personal knowledge and experience or corporate<br />

culture usually influences the individual on how to approach these tasks. This model or “roadmap”<br />

is a compilation <strong>of</strong> useful trends, processes and concepts that can be adapted to meet each unique<br />

situation, however focusing on a process for implementation. <strong>The</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> its use is the basis<br />

for knowing where your organization is in the process, pinpointing where you want to go, what<br />

you need and how to get there, i.e. your master plan!<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 23

Papers

Contextual Difficulties in IRB Deliberations –<br />

Principlist vs. Narrativist Ethical Frameworks<br />

Chris Asmann-Finch, M.S., LNHA<br />

Doctoral student, Medical Humanities<br />

Caspersen School <strong>of</strong> Graduate Studies<br />

Drew University<br />

36 Madison Avenue<br />

Madison, NJ 07940<br />

Email: asmannfinc@aol.com<br />

Abstract<br />

<strong>The</strong> Belmont Report identified three principles, respect for persons, beneficence and justice, that<br />

should guide the conduct <strong>of</strong> research involving human participants. Yet, in the absence <strong>of</strong> knowing<br />

or understanding the values <strong>of</strong> participants, whose values do IRB members’ use to evaluate the<br />

ethical principles? How do they apply them operationally to the social interactions that assure participants’<br />

opinions and choices are recognized, respected and unrestrained, or that risk and benefit<br />

have been proportionately balanced in a way meaningful to the participants? Do IRB assumptions,<br />

in fact, safeguard the ethical principles as conceptualized by the participants? <strong>The</strong>se contextual<br />

difficulties, critics claim, are reflective <strong>of</strong> ethics deliberations that fail to account for social context.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Report’s three quintessential requirements for ethical conduct in research are shaped within<br />

a principlist framework, a framework that expresses the general values underlying rules in the<br />

common morality. Narrative ethicists, on the other hand, hold the conviction that every moral<br />

situation is unique and unrepeatable, and their meaning cannot be fully captured by appealing to<br />

universal principles. This project will identify the conceptual difficulties faced by IRBs and explore<br />

the contributions each theoretical approach <strong>of</strong>fers to provide greater safeguards to participants <strong>of</strong><br />

clinical research.<br />

Text<br />

Papers<br />

<strong>The</strong> Belmont Report, created in 1974 by the National Commission for the Protection <strong>of</strong> Human<br />

Subjects <strong>of</strong> Biomedical and Behavioral Research and published in 1979, was created to establish<br />

the basic ethical principles that should guide the conduct <strong>of</strong> biomedical and behavioral research<br />

involving human participants. <strong>The</strong> Report identified three principles, or “prescriptive judgments”:<br />

respect for persons, beneficence and justice. Respect for persons included two ethical considerations,<br />

“first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons<br />

with diminished autonomy are entitled to protections.” Beneficence included convictions <strong>of</strong> doing<br />

what is in the best interest <strong>of</strong> the participant and nonmalfeasance. Finally, justice was defined as<br />

distributive justice, in the sense <strong>of</strong> “fairness in distribution” or “what is deserved” (National Commission,<br />

1979).<br />

Organizations that conduct clinical research involving humans are required to delegate oversight<br />

responsibility for protection <strong>of</strong> these ethical imperatives to Institutional Review Boards (IRB). Defined<br />

as an “administrative body” composed <strong>of</strong> scientists and nonscientists, IRB’s are “established<br />

to protect the rights and welfare <strong>of</strong> human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities<br />

conducted under the auspices <strong>of</strong> the institution with which it is affiliated” (Peckman, 2002,<br />

p.17). <strong>The</strong> IRB conducts reviews <strong>of</strong> research protocols, prospectively and periodically thereafter for<br />

the duration <strong>of</strong> the project, to assure the ethical principles have been safeguarded.<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 27

Papers<br />

<strong>The</strong> principles <strong>of</strong> respect for persons, beneficence and justice appear deceptively simple. In the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> the participants or their values, how do IRB’s safeguard these standard<br />

bioethical principles? How do they apply them operationally to the social interactions that assure<br />

participants’ considered opinions and that their choices are recognized, respected and unrestrained,<br />

or that risk and benefit have been proportionately balanced in a way meaningful to the<br />

participants?<br />

<strong>The</strong> Belmont Report instructs that the application <strong>of</strong> the general principles to the conduct <strong>of</strong><br />

research occurs through careful consideration <strong>of</strong> informed consent. <strong>The</strong> Common Rule, a federal<br />

law consolidating a number <strong>of</strong> related regulations on the topic, outlines a plethora <strong>of</strong> elements that<br />

informed consent to conduct research must address. <strong>The</strong> informed consent document must provide<br />

a description <strong>of</strong> the research protocol and an explanation <strong>of</strong> its purpose and goals. It outlines<br />

for the participant the duration <strong>of</strong> the project, treatment or non-treatment alternatives, foreseeable<br />

and unforeseeable risks and discomforts, benefits <strong>of</strong> participation, protection <strong>of</strong> privacy and confidentiality,<br />

and costs and compensation, as applicable, and how a participant can withdraw from a<br />

study (DHHS, 1991; FDA, 1981).<br />

Even though the informed consent document is considered the cornerstone <strong>of</strong> an IRB’s review and<br />

has been accused <strong>of</strong> “absorb(ing) an inordinate amount <strong>of</strong> an IRB’s time and resources” (Penslar,<br />

2002, p. 233), it has not provided unequivocal protection <strong>of</strong> the general principles. Articles on the<br />

topic number in the thousands (Sugarman et al., 1999), and a multitude focusing on the adequacy<br />

<strong>of</strong> the informed consent document have identified pr<strong>of</strong>ound shortcomings. Misunderstandings are<br />

so numerous and widely publicized that national advocacy organizations have formed to protect<br />

trial participants from these failures (Alliance for Human Research Protection).<br />

In attempts to address the problems <strong>of</strong> the informed consent document, much money and time<br />

have been spent redesigning the form. Studies focused on document format elements such as<br />

length, completeness or arrangement <strong>of</strong> content, print size, graphics and media type, as the culprit<br />

for misunderstanding have found that modifying the design does not substantially improve communication<br />

(Coyne, et al, 2003; Flory and Emanuel, 2004; Agre, et al., 2003). However, studies that<br />

focus on contextual issues, such as the context <strong>of</strong> the wording, setting, contact between researcher<br />

and participant, and illness context have improved understanding (Simin<strong>of</strong>f, 2003).<br />

Contextually, research has identified that, regardless <strong>of</strong> the reading level <strong>of</strong> the document, wording<br />

is problematic because there is no uniform understanding <strong>of</strong> the clinical trial’s impact on a<br />

participant’s life. One study found “serious side effects” required a scientific background to understand<br />

the meaning <strong>of</strong> “side effects” as they were intended by the sponsor and required a personal<br />

value judgment to fully appreciate the impact <strong>of</strong> “serious” on one’s life (Hochhauser, 2003, pp. 8-9).<br />

Serious pain means different things to different people. Another found that contrary to a clinician’s<br />

common understanding <strong>of</strong> “experiment” and “research,” a participant without a clinical background<br />

considered “experiment” to imply using drugs whose effects were unknown, whereas “research”<br />

was a process whereby doctors “were trying to find out more about you in depth” (Appelbaum,<br />

et al., 1987, p. 22). My own research found that administrative matters such as boilerplate<br />

language for medical record access could be misconstrued as prognosis for survival. “We would<br />

like to keep track <strong>of</strong> your medical condition for three years,” distorted hope for the participants<br />

whose projected mortality was measured in months, not years. While participants interpreted<br />

wording in the context <strong>of</strong> their personal lives, medical pr<strong>of</strong>essionals did so within the context <strong>of</strong><br />

their medical and administrative expertise – their pr<strong>of</strong>essional lives. Thus, the contextual interpretation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the language created vastly different meanings for the different readers. Such differences<br />

had a pr<strong>of</strong>ound impact on informed consent.<br />

28 2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book

Papers<br />

Additionally, participants and physician-researchers alike contextualize their relationship in ways<br />

that create complex effects. Studies found that participants held tenaciously to the belief that medical<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals will always act in the best interest <strong>of</strong> the participant regardless <strong>of</strong> the wording <strong>of</strong><br />

the informed consent document creating a therapeutic misconception (Kusek, et al., 1996; Schron,<br />

Wassertheil-Smoller, & Pressel, 1997; J<strong>of</strong>fe, et al., 2001; Miller, 2000) and a failure to understand<br />

the ramifications <strong>of</strong> randomization in their care (Mills, et al., 2003). Physicians validated these<br />

misconceptions by weaving standard doctor-patient language <strong>of</strong> individual care and hope with researcher-subject<br />

language <strong>of</strong> generalized knowledge and unknown outcomes (Sankar, 2004; Miller<br />

and Brody, 2003; Vanderpool and Weiss, 1987).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se contextual difficulties in the interpretation <strong>of</strong> protocols by participants, critics claim, are reflective<br />

<strong>of</strong> how ethics deliberations fail to account for social context (Sankar, 2004; Pullman, 2002;<br />

Galarneua, 2002). Such criticism has been debated in the bioethics community in recent years<br />

between those who hold a view that universal principles are at the center <strong>of</strong> moral life and those<br />

who believe communication is at the center (McCarthy, 2003, p. 65). <strong>The</strong> former belief is generally<br />

labeled principlism; the latter, has become known as narrative ethics.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Belmont Report’s “three quintessential requirements for ethical conduct in research” (Penslar,<br />

2002, p. 233) are shaped within a principlist framework, a framework that expresses the general<br />

values underlying rules in the common morality, and then function as guidelines for pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

ethics leaving considerable room for judgment (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001, p. 12). In<br />

fact, <strong>The</strong> Report was specifically designed as a general framework. It states that the principles are<br />

“stated at a level <strong>of</strong> generalization that should assist scientists, subjects, reviewers and interested<br />

citizens to understand the ethical issues inherent in research involving human subjects.” It goes on<br />

to say that the objective <strong>of</strong> such a design is to “provide an analytic framework that will guide the<br />

resolution <strong>of</strong> ethical problems arising from research involving human subjects” (National Commission,<br />

1979). Feminist theorists counter, however, that a principlist framework, with its topdown,<br />

deductive approach, assumes participants share the same experience creating opportunities<br />

for dominant culture to override an individual’s interpretation and values, and interpret them<br />

in homogenized, usually masculine ways (Donchin, 2001; Potts, et al., 2004) that tend to claim<br />