Vietnam

Swarthmore College Bulletin (June 2006) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (June 2006) - ITS

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

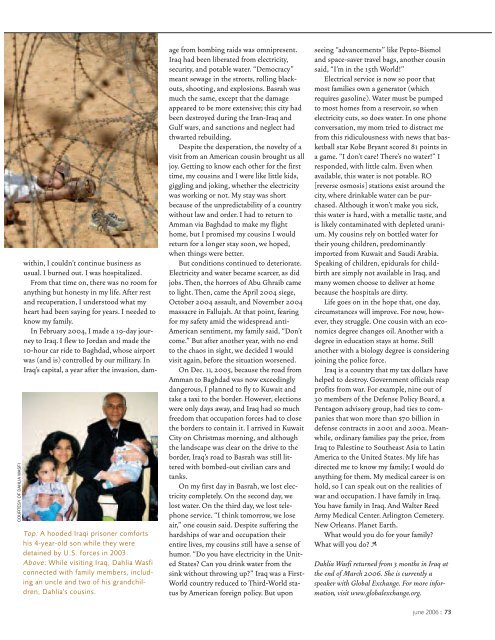

COURTESY OF DAHLIA WASFITop: A hooded Iraqi prisoner comfortshis 4-year-old son while they weredetained by U.S. forces in 2003.Above: While visiting Iraq, Dahlia Wasficonnected with family members, includingan uncle and two of his grandchildren,Dahlia's cousins.within, I couldn’t continue business asusual. I burned out. I was hospitalized.From that time on, there was no room foranything but honesty in my life. After restand recuperation, I understood what myheart had been saying for years. I needed toknow my family.In February 2004, I made a 19-day journeyto Iraq. I flew to Jordan and made the10-hour car ride to Baghdad, whose airportwas (and is) controlled by our military. InIraq’s capital, a year after the invasion, damagefrom bombing raids was omnipresent.Iraq had been liberated from electricity,security, and potable water. “Democracy”meant sewage in the streets, rolling blackouts,shooting, and explosions. Basrah wasmuch the same, except that the damageappeared to be more extensive; this city hadbeen destroyed during the Iran-Iraq andGulf wars, and sanctions and neglect hadthwarted rebuilding.Despite the desperation, the novelty of avisit from an American cousin brought us alljoy. Getting to know each other for the firsttime, my cousins and I were like little kids,giggling and joking, whether the electricitywas working or not. My stay was shortbecause of the unpredictability of a countrywithout law and order. I had to return toAmman via Baghdad to make my flighthome, but I promised my cousins I wouldreturn for a longer stay soon, we hoped,when things were better.But conditions continued to deteriorate.Electricity and water became scarcer, as didjobs. Then, the horrors of Abu Ghraib cameto light. Then, came the April 2004 siege,October 2004 assault, and November 2004massacre in Fallujah. At that point, fearingfor my safety amid the widespread anti-American sentiment, my family said, “Don’tcome.” But after another year, with no endto the chaos in sight, we decided I wouldvisit again, before the situation worsened.On Dec. 11, 2005, because the road fromAmman to Baghdad was now exceedinglydangerous, I planned to fly to Kuwait andtake a taxi to the border. However, electionswere only days away, and Iraq had so muchfreedom that occupation forces had to closethe borders to contain it. I arrived in KuwaitCity on Christmas morning, and althoughthe landscape was clear on the drive to theborder, Iraq’s road to Basrah was still litteredwith bombed-out civilian cars andtanks.On my first day in Basrah, we lost electricitycompletely. On the second day, welost water. On the third day, we lost telephoneservice. “I think tomorrow, we loseair,” one cousin said. Despite suffering thehardships of war and occupation theirentire lives, my cousins still have a sense ofhumor. “Do you have electricity in the UnitedStates? Can you drink water from thesink without throwing up?” Iraq was a First-World country reduced to Third-World statusby American foreign policy. But uponseeing “advancements” like Pepto-Bismoland space-saver travel bags, another cousinsaid, “I’m in the 15th World!”Electrical service is now so poor thatmost families own a generator (whichrequires gasoline). Water must be pumpedto most homes from a reservoir, so whenelectricity cuts, so does water. In one phoneconversation, my mom tried to distract mefrom this ridiculousness with news that basketballstar Kobe Bryant scored 81 points ina game. “I don’t care! There’s no water!” Iresponded, with little calm. Even whenavailable, this water is not potable. RO[reverse osmosis] stations exist around thecity, where drinkable water can be purchased.Although it won’t make you sick,this water is hard, with a metallic taste, andis likely contaminated with depleted uranium.My cousins rely on bottled water fortheir young children, predominantlyimported from Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.Speaking of children, epidurals for childbirthare simply not available in Iraq, andmany women choose to deliver at homebecause the hospitals are dirty.Life goes on in the hope that, one day,circumstances will improve. For now, however,they struggle. One cousin with an economicsdegree changes oil. Another with adegree in education stays at home. Stillanother with a biology degree is consideringjoining the police force.Iraq is a country that my tax dollars havehelped to destroy. Government officials reapprofits from war. For example, nine out of30 members of the Defense Policy Board, aPentagon advisory group, had ties to companiesthat won more than $70 billion indefense contracts in 2001 and 2002. Meanwhile,ordinary families pay the price, fromIraq to Palestine to Southeast Asia to LatinAmerica to the United States. My life hasdirected me to know my family; I would doanything for them. My medical career is onhold, so I can speak out on the realities ofwar and occupation. I have family in Iraq.You have family in Iraq. And Walter ReedArmy Medical Center. Arlington Cemetery.New Orleans. Planet Earth.What would you do for your family?What will you do? TDahlia Wasfi returned from 3 months in Iraq atthe end of March 2006. She is currently aspeaker with Global Exchange. For more information,visit www.globalexchange.org.june 2006 : 73