TRUTH

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2006) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2006) - ITS

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

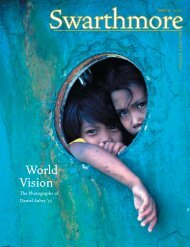

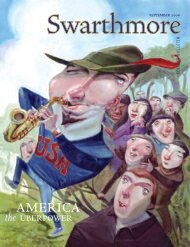

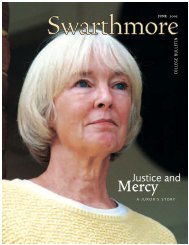

Other criticisms that Burke mentions—that the TRC dealt only with “gross violationsof human rights,” ignoring the systematicbrutality of apartheid’s structure;that launching the commission was a wastefuluse of resources; and that the TRC’sapproach implied some sort of moral paritybetween those who rebelled againstapartheid and those who were its arms—arecommonly referenced in the academic literatureon the commission.“I think a lot of people thought that, inthe end, this was a white liberal’s dream ofjustice—abstract, intellectual, about memoryand history. That isn’t what people whosuffered the hard knocks of apartheid want.It’s what eggheads and lawyers and academicslike,” says Burke. “But apartheid was ahuman phenomenon; it needs understanding.With some degree of genuine curiosity,we need to know why people did thesethings.”Villa-Vicencio, whose department waseffectively responsible for writing the TRC’sfinal report, added that when you’re close tothe commission, you can see its shortcomingsmore clearly. “But, undoubtedly,” hesays, “the success of our process is thatnobody, black or white, can ever say, everagain, that they did not know that sufferinghappened.”Lessac doesn’t disregard the criticisms ofthe TRC but sees them as incidental, givenSouth Africa’s peaceful reconstruction.“What can we expect?” he asks. “We couldnitpick our planet’s way to self-destructionif we don’t recognize that flawed avenues ofprogress often are the only avenues worthpursuing.“At a moment in time, the TRC avoided abloodbath; at a moment in time, it put thetruth on the table,” Lessac says. “At a momentin time, it said, ‘Let’s get on with it.’“If it wasn’t forgiveness, it was a potentialfor forgiveness. If it’s not true reconciliation,at least people behave as if they werereconciled. What if that were the only thingthat really happened?“Even if reconciliation and forgivenessmean nothing more than, ‘I’m going tobreak this cycle of vengeance,’ it’s still astep. It’s a first step.”Truth in Translation has attracted powerfulbackers and rave reviews (see the Bulletin’sreview by Karen Birdsall ’94, page 18). ArchbishopTutu wrote a letter of support for theproject, and other supporters and advisorsinclude Villa-Vicencio; Barbara Masekela,South African ambassador to the UnitedStates; Alex Boraine, deputy chairperson ofthe TRC and founding president of theInternational Center for Transitional Justice;and Anthony Lake, a former nationalsecurity advisor in the Clinton administrationand, currently, a Georgetown Universityprofessor. Hugh Masekela, a South Africanjazz great, composed the show’s music,incorporating excerpts from the original testimonyin the lyrics. Truth in Translation ismusical, but not a musical, Lessac stresses:“In South Africa, music just erupts. It comesout of a need or a celebration, or it comesTruth in Translation played for 22 performancesin Johannesburg in September,and will run from mid-February to earlyMarch in Cape Town. Lessac hopes totake it to conflict zones such as the Balkans,Sierra Leone, and Northern Ireland.out of an anger, or it comes as a weapon.”Max du Preez, a South African journalist,author, and documentary filmmaker, followedthe cast to Rwanda. He wrote in aSept. 1 Mail & Guardian Online article thatTruth in Translation “is pushing the boundariesof South African theatre and will mostlikely be seen as the most important play inrecent times.”PHOTOGRAPHS BY JEFF BARBEE/BLACK STAR22 : swarthmore college bulletin