archaeology

RSGS-The-Geographer-Spring-2015

RSGS-The-Geographer-Spring-2015

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

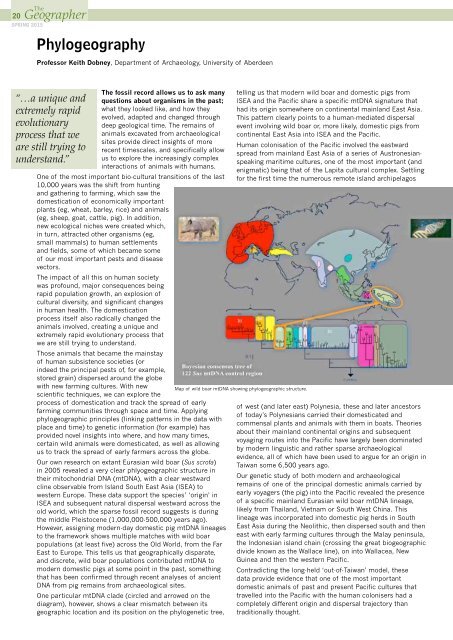

20SPRING 2015PhylogeographyProfessor Keith Dobney, Department of Archaeology, University of Aberdeen“…a unique andextremely rapidevolutionaryprocess that weare still trying tounderstand.”The fossil record allows us to ask manyquestions about organisms in the past;what they looked like, and how theyevolved, adapted and changed throughdeep geological time. The remains ofanimals excavated from archaeologicalsites provide direct insights of morerecent timescales, and specifically allowus to explore the increasingly complexinteractions of animals with humans.One of the most important bio-cultural transitions of the last10,000 years was the shift from huntingand gathering to farming, which saw thedomestication of economically importantplants (eg, wheat, barley, rice) and animals(eg, sheep, goat, cattle, pig). In addition,new ecological niches were created which,in turn, attracted other organisms (eg,small mammals) to human settlementsand fields, some of which became someof our most important pests and diseasevectors.The impact of all this on human societywas profound, major consequences beingrapid population growth, an explosion ofcultural diversity, and significant changesin human health. The domesticationprocess itself also radically changed theanimals involved, creating a unique andextremely rapid evolutionary process thatwe are still trying to understand.Those animals that became the mainstayof human subsistence societies (orindeed the principal pests of, for example,stored grain) dispersed around the globewith new farming cultures. With newscientific techniques, we can explore theprocess of domestication and track the spread of earlyfarming communities through space and time. Applyingphylogeographic principles (linking patterns in the data withplace and time) to genetic information (for example) hasprovided novel insights into where, and how many times,certain wild animals were domesticated, as well as allowingus to track the spread of early farmers across the globe.Our own research on extant Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa)in 2005 revealed a very clear phlyogeographic structure intheir mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), with a clear westwardcline observable from Island South East Asia (ISEA) towestern Europe. These data support the species’ ‘origin’ inISEA and subsequent natural dispersal westward across theold world, which the sparse fossil record suggests is duringthe middle Pleistocene (1,000,000-500,000 years ago).However, assigning modern-day domestic pig mtDNA lineagesto the framework shows multiple matches with wild boarpopulations (at least five) across the Old World, from the FarEast to Europe. This tells us that geographically disparate,and discrete, wild boar populations contributed mtDNA tomodern domestic pigs at some point in the past, somethingthat has been confirmed through recent analyses of ancientDNA from pig remains from archaeological sites.One particular mtDNA clade (circled and arrowed on thediagram), however, shows a clear mismatch between itsgeographic location and its position on the phylogenetic tree,telling us that modern wild boar and domestic pigs fromISEA and the Pacific share a specific mtDNA signature thathad its origin somewhere on continental mainland East Asia.This pattern clearly points to a human-mediated dispersalevent involving wild boar or, more likely, domestic pigs fromcontinental East Asia into ISEA and the Pacific.Human colonisation of the Pacific involved the eastwardspread from mainland East Asia of a series of Austronesianspeakingmaritime cultures, one of the most important (andenigmatic) being that of the Lapita cultural complex. Settlingfor the first time the numerous remote island archipelagosMap of wild boar mtDNA showing phylogeographic structure.of west (and later east) Polynesia, these and later ancestorsof today’s Polynesians carried their domesticated andcommensal plants and animals with them in boats. Theoriesabout their mainland continental origins and subsequentvoyaging routes into the Pacific have largely been dominatedby modern linguistic and rather sparse archaeologicalevidence, all of which have been used to argue for an origin inTaiwan some 6,500 years ago.Our genetic study of both modern and archaeologicalremains of one of the principal domestic animals carried byearly voyagers (the pig) into the Pacific revealed the presenceof a specific mainland Eurasian wild boar mtDNA lineage,likely from Thailand, Vietnam or South West China. Thislineage was incorporated into domestic pig herds in SouthEast Asia during the Neolithic, then dispersed south and theneast with early farming cultures through the Malay peninsula,the Indonesian island chain (crossing the great biogeographicdivide known as the Wallace line), on into Wallacea, NewGuinea and then the western Pacific.Contradicting the long-held ‘out-of-Taiwan’ model, thesedata provide evidence that one of the most importantdomestic animals of past and present Pacific cultures thattravelled into the Pacific with the human colonisers had acompletely different origin and dispersal trajectory thantraditionally thought.