Ripcord Adventure Journal 1.2 Second Edition

In this issue, our second, we venture widely in our quest to find great adventures. From an article written and sent from Princess Elisabeth Station in Antarctica we venture along the Omo River to meet Ethiopian tribes who are holding on to their authentic way-of-life in the face of commercialisation and tourism. We send a couch potato to climb Mount Fuji in Japan while others wander the ancient Roman roads in Transylvania, venture up Mount Toubkal and taste wondrous epicurean delights in Morocco. Finally we hear of the exploits of the explorer Charles Howard-Bury and the Everest Reconnaissance expedition

In this issue, our second, we venture widely in our quest to find great adventures. From an article written and sent from Princess Elisabeth Station in Antarctica we venture along the Omo River to meet Ethiopian tribes who are holding on to their authentic way-of-life in the face of commercialisation and tourism. We send a couch potato to climb Mount Fuji in Japan while others wander the ancient Roman roads in Transylvania, venture up Mount Toubkal and taste wondrous epicurean delights in Morocco. Finally we hear of the exploits of the explorer Charles Howard-Bury and the Everest Reconnaissance expedition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 1 | Number 2 | <strong>Second</strong> <strong>Edition</strong><br />

RAJ <strong>1.2</strong>

A Letter from the Editor<br />

Welcome to <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

In this issue, our second, we venture widely in our quest to find<br />

great adventures. From an article written and sent from Princess<br />

Elisabeth Station in Antarctica, we venture along the Omo River to<br />

meet Ethiopian tribes who are holding on to their authentic way-oflife<br />

in the face of commercialisation and tourism. We read how a<br />

couch potato climbed Mount Fuji in Japan. Our writers have<br />

wandered along the ancient Roman roads in Transylvania, climbed<br />

Mount Toubkal and tasted wondrous epicurean delights in<br />

Morocco. Finally, the biography of a little known Anglo-Irish<br />

explorer leads us on a journey to Everest.<br />

We aim to be the home of authentic, adventure travel writing, which<br />

serves as a starting point for personal reflection, study and new<br />

journeys.<br />

On behalf of the editorial, writing and design team I wish to thank<br />

our sponsors Redpoint Resolutions and the World Explorers<br />

Bureau for their continued support.<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

Editor in Chief, <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

www.ripcordadventurejournal.com<br />

www.ripcordtravelprotection.com

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> First Published February 2015 by<br />

Redpoint Resolutions & World Explorers Bureau. All articles and<br />

images © 2015 of the respective Authors and Photographers.<br />

<strong>Second</strong> <strong>Edition</strong> © March 2017<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including<br />

photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods,<br />

without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the<br />

case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain<br />

other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.<br />

For permission requests, general enquiries or sponsorship<br />

opportunities, contact the publisher:<br />

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>: info@ripcordadventurejournal.com

"The seventh wave is said to be the worst,<br />

the one that does the damage in the<br />

turmoil of an ocean gale. Modern<br />

oceanographers know this is just a<br />

superstition of the sea; they have complex<br />

wave-train theories and the laws of wave<br />

mechanics to prove it. But still the notion<br />

of the seventh wave lingers on; and<br />

clinging to the helm of a small open boat in<br />

the heaving waters of a bad Atlantic<br />

storm, one's temptation to count waves is<br />

irresistible."<br />

Tim Severin<br />

"The Brendan Voyage"

RIPCORD<br />

ADVENTURE<br />

JOURNAL<br />

<strong>1.2</strong><br />

Editor in Chief<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

Featuring<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

Jos Van Hemelrijck<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

Fearghal O'Nuallain<br />

Kieran Creevy<br />

Ruth Illingworth<br />

<strong>Second</strong> Editon<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

Paul Devaney<br />

Terry Sharrer<br />

Charlotte Baker<br />

Weinert<br />

Publishers<br />

Redpoint Resolutions<br />

& World Explorers<br />

Bureau<br />

WWW.RIPCORDADVENTUREJOURNAL.COM

Contents<br />

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

The land beyond the forest<br />

Fearghal O'Nuallain<br />

Terroir: Morocco<br />

Kieran Creevy and Claire Burge<br />

Charles Howard-Bury<br />

Ruth Illingworth<br />

Contributors and credits<br />

1<br />

23<br />

33<br />

49<br />

79<br />

95<br />

109<br />

139

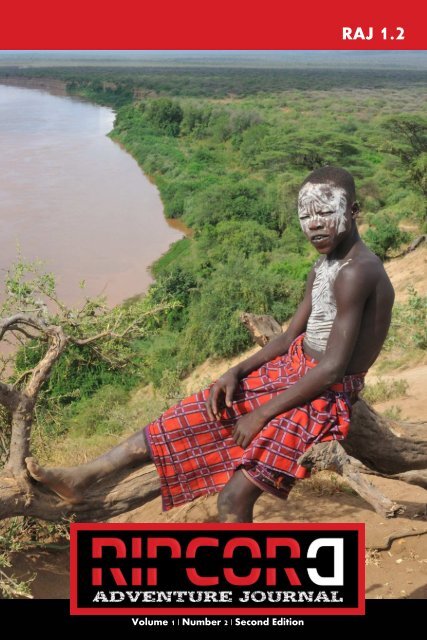

The tribes that time<br />

forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

1

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

A truly remarkable wooded valley lay below, its carpet of trees<br />

backed by mountains that cut their sharp shape in the hazy sky. The<br />

bright, baking sun beat down on me and my driver, Tsegay, his<br />

short-cropped wiry hair sitting atop a stern face that illuminated<br />

whenever he smiled, which was often. His softly spoken voice<br />

broke the silence. “That is the Omo Valley.”<br />

Much lay in wait in this valley in the south-west of Ethiopia<br />

bordering Sudan and Kenya – a place where people of different<br />

tribes scar, paint and pierce their bodies, where women are publicly<br />

whipped to demonstrate their loyalty, and where men run naked<br />

across bulls to prove their manhood. We returned to the maroon<br />

and silver Nissan Patrol to bump and skid along the dirt roads that<br />

kicked clouds of dust in our wake. It was the first of many similar<br />

journeys during the forthcoming week.<br />

We had travelled for perhaps a couple of hours, the sameness of the<br />

scenery dulling the sense of time, when suddenly on our right side<br />

appeared a collection of two dozen sizable wooden huts within a<br />

1

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

spacious clearing. It was a village of the Arbore tribe. Once out of<br />

the vehicle, I encountered a practice that elicits much debate<br />

amongst those who visit the Omo Valley – namely the payment of a<br />

fee to take photographs. The problems of this practice quickly<br />

became evident. Upon our arrival, the Arbore people rushed from<br />

their huts to form a long line near the vehicle hoping to be chosen,<br />

and paid, to be photographed. It felt incredibly forced, and though I<br />

am unsure where this practice emanated from, obediently lining in<br />

an orderly fashion was inconsistent with every other activity I<br />

witnessed in the Omo Valley. This appeared imposed from outside.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

I lowered my head, undecided if I wanted to participate in this<br />

awkward spectacle, but there was no retreat, for the Arbore would<br />

aggressively pursue those with cameras to photograph them. They<br />

would grab your arm or camera and verbally badger for a picture;<br />

this whirlwind of activity and attention was almost overwhelming. I<br />

wandered far away from the scene with one Arbore woman in order<br />

to distance myself from the selection line, which on further<br />

reflection, looked more and more like a circus with paid performers.<br />

By having her with me, it seemed to keep the others away, but that<br />

only lasted until she dawdled away after the photo shoot, for the<br />

chaos descended on me again.<br />

After a difficult photography session, I returned to the vehicle – and<br />

upon closing the door found myself inside a serene silent shelter<br />

from the buffeting verbal tempest outside. My first tribe visit<br />

proved to be a confronting experience. In 2010, the payment<br />

amounts were small, one or two Birr (approximately 15 cents at the<br />

time), whereas a larger amount (at least 250 birr) is payable as a<br />

village admission fee. However, these prices have increased many<br />

times over since then.<br />

While still musing on the most responsible method to approach<br />

photography in the Omo Valley, we proceeded to the small town of<br />

Turmi. Our plans to arrive in the late afternoon were thwarted by<br />

the road conditions. Shortly after Tsegay had changed a tyre due to<br />

a puncture, he lent out the window, and muttered something under<br />

his breath before stopping to attend to the second puncture in the<br />

space of half an hour. With little phone coverage and almost no<br />

2

3

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

traffic in this part of the Valley, any serious vehicle issues would<br />

cause immense problems. Since we now had no spare tyres, a third<br />

puncture would leave us stranded.<br />

The journey through a terrain of trees upon sandy soil continued<br />

after sunset, and the surrounding scene was one of absolute<br />

darkness. The vehicle’s headlights were the only source of<br />

illumination on this landscape devoid of any other light source –<br />

nothing coming from huts, none marking any streets, and no other<br />

vehicles. Avoiding any further punctures, we arrived in the small<br />

town of Turmi, and the faint orange glow of the occasional street<br />

light enabled me to discern a town comprised of a single road<br />

populated with squat flat-roofed buildings on either side of the<br />

carriageway.<br />

Our late arrival on a cool evening in Turmi meant that<br />

accommodation was limited to the diabolical Green Hotel. If one<br />

considered that the hotels of the world formed a human body, and a<br />

doctor needed to give this collective body an enema, then they<br />

would insert it into the Green Hotel. It is the foulest place I have<br />

ever stayed in, the one remaining room was small, stuffy with<br />

peeling green paint and a broken fly screen that allowed entry to<br />

malaria-carrying mosquitoes. The linen was a public health risk and<br />

as an added feature of this five dollar room, it held a complimentary<br />

pile of condoms, some opened. These were obviously used by the<br />

clients of the women who frequented the nearby bar whose music<br />

reverberated through the entire room. Though the music finally<br />

ceased at 1am, it was followed by a frightful fight between highly<br />

inebriated women who charged by the hour and their equally<br />

drunken clients.<br />

After a broken sleep and pitiful breakfast, happiness again returned<br />

when I saw the Green Hotel disappear in the rear-view mirror.<br />

With both punctured tyres now repaired, two hours of driving<br />

along moderately good roads saw our arrival in the small town of<br />

Omorante, only 40 kilometres from the Sudanese border. It was a<br />

very warm and dusty place where people languidly shifted along the<br />

roads lined with forlorn shops, whilst goats and other animals<br />

occupied themselves in the search for food.<br />

4

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

After registering at the police station, there was a choice of two<br />

hotels, one dire, the other dismal. As with most accommodation in<br />

the Omo Valley, the toilets were fetid, the showers cold, and the<br />

food average. The latter was the biggest disappointment, for<br />

Ethiopia has an excellent cuisine – arguably the best in Africa – but<br />

sadly, that quality was absent in the Omo Valley. The main reason to<br />

visit Omorante was to cross the Omo River to visit the Galeb tribe.<br />

However, my desire for embarking on this short voyage quickly<br />

evaporated when watching the elongated and unstable boats carved<br />

from a single tree plying the fast flowing Omo River. The boatmen<br />

were obvious masters of their craft for they would direct the boat<br />

close to the steep river bank some distance upstream before<br />

swinging to the centre of the river and being hurtled downstream<br />

whilst crossing to the other side. Even an experienced swimmer like<br />

me would have trouble surviving in those treacherous waters in the<br />

case of a capsize. Some adventures are best left for another time.<br />

So far the expedition to the Omo Valley had been beset by barriers<br />

and difficulties with meagre rewards – it had been an inauspicious<br />

start to the adventure. Thankfully, the situation improved on the<br />

third day when Tsegay drove me to a village called Kolcho inhabited<br />

by the Karo tribe. Our vehicle encountered the roughest dirt road<br />

conditions of this journey, and we occasionally needed to navigate<br />

around gaping holes that threatened to swallow the vehicle, and<br />

manoeuvre past almost vertical declivities – Tsegaye’s driving was<br />

superb.<br />

We passed a naked man standing on a sandy dry riverbed<br />

overlooking the few cattle in his possession. His lean dark frame<br />

stood motionless, supporting himself on the long stick which he<br />

held in one hand. There was not even a hint of modernity in this<br />

scene that could have occurred thousands of years ago, rather than<br />

in the 21st century.<br />

After much jarring of bones and inhaling of dust, we arrived at<br />

Kolcho nestled near to a stunning lookout with a magnificent grand<br />

and wide panorama over the Omo River far below. This was one<br />

village worthy of an entrance fee, for not only were the views<br />

5

6

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

impressive, but so too was the village. Covering a large area with a<br />

multitude of large huts that were relatively densely packed, it was a<br />

tremendous place to explore the numerous paths that meandered<br />

between the habitations.<br />

The Karo were a very pleasant people, it was possible to walk<br />

around unaccompanied and receive only occasional, polite requests<br />

for photographs. In this village with neither electricity nor water<br />

supply, I could quietly observe Karo pastoral life; women would<br />

grind grains for dinner and larger children would play with their<br />

younger and smaller siblings by sitting them on a large piece of<br />

metal and drag them along at speed. It was an idyllic scene of<br />

simple and unaffected contentment. The Karo people deserved their<br />

title as the region’s best body painters as they sported elaborate and<br />

full decorations but the reason for this artistry was never fully<br />

explained to me, apart from the obvious atheistic and decorative<br />

aspects.<br />

I was sauntering around the village when someone behind me spoke<br />

in perfect English “How are you?” I had not sighted another<br />

foreigner, but could have been mistaken since there were so many<br />

huts where one could loiter unseen. So imagine my surprise when I<br />

turned to see a Karo woman with painted face and numerous<br />

necklaces squatting by her modest hut. She only spoke a few words<br />

of English, but was the only person who was able to communicate<br />

with me verbally. For everyone else, it was via gestures and the<br />

international language of a smile.<br />

One vividly painted Karo warrior and I formed a particularly strong<br />

bond. Proudly carrying his automatic weapon, and with red tinge in<br />

his eyes that were accentuated by his white painted face, I showed<br />

him images of other tribes which seemed to interest him greatly. He<br />

posed for numerous photographs and we shared a smile and laugh<br />

whilst reviewing the images. When it came time to depart, he gave<br />

me a genuinely emotional farewell, I could discern it in his eyes. He<br />

did not want me to leave, and I felt the same way. There was so<br />

much more to learn from him about his life and his village. It is<br />

heartening to know that genuine warmth can be established between<br />

people from extremely different cultures and different languages<br />

7

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

within a brief time.<br />

We returned to Turmi and I decided to pay a relative premium for a<br />

spacious cabin at the Evangadi Lodge with cold showers and a toilet<br />

that did not make me shudder. This Monday was a special day in the<br />

town, for not only was it market day, but a Hamer initiation<br />

ceremony would occur later that afternoon. The Hamer people are<br />

famed throughout Ethiopia, their beautiful women plat their hair<br />

and coat it with a distinctive red clay, and the men are equally<br />

handsome. I warmed to the Hamer tribe more than any other, they<br />

were gentle and a smile never seemed far away.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The market was the best in the Omo Valley, as hundreds of Hamer<br />

converged to interact and trade goods in an expectedly relaxed<br />

environment. I espied a few women with large, wide scars on their<br />

backs and arms, which I thought odd for a seemingly placid people.<br />

It felt surreal to watch this glimpse of tribal life and it was not the<br />

only time this journey that felt as if I had stumbled into the middle<br />

of a National Geographic documentary.<br />

After losing track of time, I needed to hurry to attend the Hamer<br />

initiation ceremony, one of the highlights of any Omo Valley visit.<br />

This ceremony is an elaborate affair which allows the male initiate,<br />

if successful, to commence the process of choosing a wife. The<br />

ceremony lasts hours and commences with women adorned in<br />

bangles and carrying small noisy horns, jumping in unison and<br />

following each other in a tight circle. This celebration is not so<br />

unusual, but the same could not be said of the public whipping that<br />

followed.<br />

Tradition dictates that any relative of the initiate can prove their<br />

loyalty by being publicly scourged with a thin, destructive whip.<br />

The process involves a woman approaching any Hamer adult male<br />

to deliver the punishment, but some men were reluctant to take<br />

part, and they had less enthusiasm for the practice then some of the<br />

women who needed to cajole them for another lashing. Supposedly<br />

a woman will plead to a man “Hit me,” he will respond “No,” and<br />

her retort being “You are no better than a woman!” at which time<br />

she would receive a single strike. Some women proudly displayed<br />

8

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

numerous open welts on their back, but not every female was<br />

similarly enraptured by the societal pressure. I espied a forlorn<br />

teenager with doleful eyes who had just received her first whipping;<br />

I pointed to a long thin cut on her back and she expressed her<br />

feelings by grimacing.<br />

While the women bravely bore their wounds in silence, the men<br />

continued the ceremony by engaging in ritualistic face painting – a<br />

rather genteel task compared to what the women endured. Most<br />

memorable was that the packed group of men squatting in the shade<br />

of an enormous tree were so incredibly intense. The concentration<br />

of the painters’ faces were immense, but it paled when compared to<br />

the recipients, whose eyes were simultaneously both calm and<br />

fervent; the gaze of men searching their inner thoughts as if in a<br />

trance.<br />

The gathered crowd walked the one kilometre along a dirt road for<br />

the climax. Whilst the Hamer men gathered around the initiate in a<br />

tight huddle, twelve reluctant bulls from a collection of many more<br />

were forcibly placed beside each other in a line, as the women<br />

danced, jingled and played their horns around the corralled beasts.<br />

Some of the beasts almost broke free to wreak havoc on their<br />

handlers, but they was thankfully subdued. With scores of men<br />

holding the bulls in place under cloudy skies, the naked initiate<br />

stood at the far end as the women increased their noise to a<br />

crescendo and the tourists paused with cameras poised. Suddenly<br />

the initiate leapt onto the first bull and quickly, but ever so carefully,<br />

stepped on each animal before jumping on the ground near me, at<br />

which time I detected his expression of absolute concentration<br />

flicker for a moment to one of momentary relief. He returned from<br />

whence he came, again stepping on each of the bulls, and he<br />

repeated this whole process two more times. It took less than a<br />

minute for the initiation to be successfully completed and the<br />

foreigners applauded, which seemed incongruent for this traditional<br />

ceremony.<br />

The assembled onlookers dispersed and when leaving the area we<br />

offered a seat in our vehicle to a Hamer teenager, his youthful dark<br />

face a start contrast to his shining white teeth. He saw me reviewing<br />

9

10

11

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

the images on my camera and requested to see the picture of the<br />

naked initiate crossing the bulls.<br />

I showed him the picture, and he asked me, “Get closer,” so I<br />

zoomed into the initiate alone.<br />

The teenager looked over the body and commented. “He is a strong<br />

man, and has a strong gun...” which referred to the size of the man’s<br />

genitalia, “he will have good children.”<br />

He looked away from the camera before stating, “My initiation<br />

ceremony will be soon.”<br />

“Really, that is great news,” I replied, “When will it be?”<br />

He paused before answering, “In a few weeks. I do not know the<br />

day.”<br />

“Will it be a big ceremony like this one?” I enquired.<br />

“No, a small one. There will be no women, only men,” he stated.<br />

“Will there any faranjis?” I asked, that being local word to describe<br />

foreigners.<br />

“No, only the men of my tribe.”<br />

“So you can choose if you want a big or small ceremony.”<br />

“Yes I can. I will have a small ceremony. Not many people.”<br />

We had arrived at my hotel, “I wish you the best for the ceremony.”<br />

“Thank you,” he responded by flashing that brilliant white smile<br />

and he exited the vehicle.<br />

The only town of note in the Omo Valley is Jinka, it even had<br />

mobile phone coverage. As we approached I remember hearing that<br />

Jinka once had a airport used for regional flights, so I asked Tsegay.<br />

12

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

“Did Ethiopian Airlines used to fly to Jinka?”<br />

“Yes, but they stopped it not long ago.”<br />

“Why?”<br />

Tsegay gave me one of those of his typical wry smiles. “You will<br />

know when you see the airstrip.”<br />

And sure enough I did, for there in the middle of Jinka’s low rise<br />

buildings sat what was once the airport, the former airstrip an<br />

uneven surface now populated with animals grazing on tufts of<br />

grass. Any plane landing on this surface, even without the grass and<br />

bovines, would be a risky venture.<br />

“Now you see why,” stated Tsegay.<br />

I laughed and nodded in reply.<br />

Rambling around the dirt streets one late afternoon, many friendly<br />

people approached me who keenly wished to talk and swap stories.<br />

So many were interested in my country of origin, and what I<br />

thought of Ethiopia and the Omo Valley. When the sunset’s scarlet<br />

light painted the buildings with its soft hue, I returned to my room<br />

where I saw my reflection in a mirror for the first time in many days<br />

and was surprised at my gaunt appearance. Subconsciously I had<br />

reacted to the poor state of the food and the worse state of the<br />

toilets by eating little, thus allowing me to minimise my exposure to<br />

both.<br />

Jinka was the base to meet the most famous and feared tribe in the<br />

Omo Valley; the aggressiveness of the Mursi is known by many, and<br />

some travellers have refused to visit due to episodes such as stone<br />

throwing and their predilection for alcohol. However, this<br />

promised an unforgettable experience, so undaunted we proceeded<br />

to the Mago National Park where the tribe resides. A sign at the<br />

park’s entrance states: No Automatic Weapons, but this regulation is<br />

flagrantly ignored by the Mursi.<br />

13

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

At the final checkpoint we were required to acquire the services of<br />

an armed guard, and whilst organising this service, we met a<br />

departing group of half a dozen European tourists who had stayed<br />

with the Mursi the previous evening.<br />

“How was your night?” I asked a young unshaven man.<br />

He glanced at me with weary eyes. “It was...difficult. I had very<br />

little sleep,” as he turned and walked away. That was not reassuring.<br />

With the armed guard sitting beside me in the now dirt encased<br />

Nissan Patrol, we encountered another potential peril. Apart from<br />

the Omo Valley’s malarial mosquitoes, the park is home to the<br />

Tsetse Fly that can inflict a most painful bite. When one of these<br />

brightly coloured insects appeared in the cabin near to the guard, he<br />

became most anxious and feverishly waved his hands and gun in the<br />

air. An agitated armed guard is never a good situation, regardless of<br />

the cause.<br />

I harboured nervousness about visiting the Mursi and the portent of<br />

silence within the vehicle reflected my thoughts. This concern was<br />

well founded, for we came upon a Mursi village to scenes of<br />

frenzied activity as two vehicles with a dozen tourists had already<br />

arrived, and the Mursi were swarming around them like a pack of<br />

sharks closing in for a kill. Women were particularly aggressive in<br />

physically seizing people for a photograph.<br />

“This is not good,” I sighed to Tsegay.<br />

“No, it’s not,” came his stoic reply, as we watched another tourist<br />

disappear behind a mass of gesticulating Mursi women.<br />

“Is it always like this?” I questioned.<br />

Tsegay nodded and quietly uttered, “Yes.”<br />

“Maybe we should wait until the other faranji leave?”<br />

“A good idea,” concurred Tsegay.<br />

14

15

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

Tsegay reversed the car and we observed tourism’s ugly side from a<br />

distance. We hoped that it would be calmer once these groups had<br />

departed, and thankfully this prediction proved correct. Once<br />

within the the small village with the simplest of huts, we noticed the<br />

ubiquitous presence of automatic weapons, even the women carried<br />

them, a practice considered abhorrent by other tribes. The reason<br />

for this convention was difficult to determine, it was either deemed<br />

necessary for protection against predators, or possible against other<br />

Mursi. This was even more confronting than the Arbore tribe, for<br />

when someone grabs your arm demanding a photo be taken, and<br />

they have an AK47 swinging from their arm, it does change the<br />

power balance of the situation strongly against the visitor.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Communicating with the tribe was protracted as conversations<br />

needed to be translated from Mursi to the national Amharic<br />

language (courtesy of the armed guard) and from Amharic into<br />

English (courtesy of Tsegay) so these stilted colloquies involved not<br />

only the Mursi and me, but two interpreters as well. Like much of<br />

the Omo Valley, it was difficult to garner a fuller understanding of<br />

the people due to the language barrier, and the Omo Valley contains<br />

many languages, each only spoken by a few thousand people. But<br />

this communication, however protracted, did make a different to<br />

our visit – when the Mursi knew we wished to learn more about the<br />

village and its people, their reaction changed. Many returned to<br />

their usual daily duties instead of focusing their energies on our<br />

presence. As the previous group discovered, heading into any tribe<br />

for a whirlwind stop just to photograph receives a less welcoming<br />

reaction than those who are prepared to linger and learn.<br />

The body decoration on the Mursi was superb, and the scarification<br />

used by both men and women tended towards the elaborate.<br />

However, the iconic image of the Omo Valley is that of the lip plate<br />

worn only by the women, and they vary in size from moderately<br />

small to more than 20 centimetres wide. This adornment is not<br />

universally utilised, but the women who chose to do so consider it<br />

an object of beauty. For those who choose to wear one, they start<br />

with smaller plates in their teenage years until reaching full-sized<br />

plates in adulthood. The plate, which has a groove around the edge<br />

where the extended lip is placed, is not worn continuously as the<br />

16

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

wearer will remove it when eating or sleeping, nor are they worn<br />

when visiting the Jinka markets as the Mursi believe that these plates<br />

appear odd to outsiders.<br />

We departed 90 minutes later, but I was disappointed by my poor<br />

reaction to the Mursi’s initial aggressiveness that allowed me to be<br />

overwhelmed for a second time on this journey. I vacillated on<br />

whether to return to the Mursi tribe the next morning. My<br />

photographs on the first visit were quite poor, my creativity<br />

bludgeoned by the intense environment. Perhaps a return was in<br />

order, and despite knowing that it would be another confrontational<br />

experience, not visiting again would be a regret.<br />

Thus, with a greater mental preparedness, we returned to two<br />

different Mursi villages. These were both smaller, received less<br />

tourists and hence less frenzy. It was such a calm contrast to the<br />

previous day. The more relaxed mood allowed me to capture better<br />

photographs, and even the sternest visage would lighten and<br />

sometimes laugh upon seeing their picture on my camera’s LCD<br />

screen. It was a pleasant conclusion to my tribal visits in the Omo<br />

Valley, and showed that generalisations about a people never<br />

account for the nuances that they, both as an individual and a<br />

collective, can possess.<br />

As we embarked on the three day journey to Ethiopia’s capital of<br />

Addis Ababa, it allowed me to reflect on the oft described vanishing<br />

tribes of the Omo Valley. These tribes as so distinct that one could<br />

determine their identity by merely looking at clothing and body<br />

adornments, but how do these tribes retain their cultures?<br />

Tourism’s negative impact includes photography payments and I<br />

was part of the problem by ceding to such. Visiting tribes where<br />

people stand in line hoping to be chosen to be photographed was<br />

most uncomfortable for all concerned.<br />

But tourism can both destroy and preserve. The Omo Valley seems<br />

to retain its culture better than many places; at least the tribes realise<br />

that their traditional lifestyle and culture provides an income, and<br />

this income encourages them to maintain their identity, even if it is<br />

at the cost of avarice. However, I sighted people in traditional tribal<br />

17

18

19

The tribes that time forgot<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

attire far away from the tourist path, so even without income from<br />

tourism, many of these practices would remain.<br />

As Tsegay drove the vehicle out of the valley, we sighted a new<br />

bitumen road being constructed. It would make the journey<br />

between Jinka and the major town before the Omo Valley, Konso,<br />

much easier and faster. Development was coming to Omo Valley<br />

and as we passed groups of workers huddles around massive<br />

machinery, I wondered with trepidation what would be the impact.<br />

Perhaps, time will not forget these tribes any longer.<br />

The completion of that road changed the Omo Valley, for the easier<br />

passage not only meant better access to health care and trading, but<br />

also meant an influx of foreign visitors who would not undertake<br />

the journey on rougher roads. One sincerely hopes that these tribes<br />

which have filled the Omo Valley with their richness for millennia,<br />

can continue to retain their identity and thrive within a truly<br />

remarkable wooded valley.<br />

20

"Over the plains of Ethiopia the sun rose<br />

as I had not seen it in seven years. A big,<br />

cool, empty sky flushed a little above a rim<br />

of dark mountains. The landscape 20,000<br />

feet below gathered itself from the dark<br />

and showed a pale gleam of grass, a sheen<br />

of water. The red deepened and pulsed,<br />

radiating streaks of fire. There hung the<br />

sun, like a luminous spider's egg, or a<br />

white pearl, just below the rim of the<br />

mountains. Suddenly it swelled, turned<br />

red, roared over the horizon and drove up<br />

the sky like a train engine. "<br />

Doris Lessing<br />

"Going Home"<br />

21

A field trip in<br />

Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

25<br />

22

“Why don’t we go back?” Alain Hubert whispered.<br />

“What?” I said<br />

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

“Yes, we should go back and build a new Belgian Polar Station. But<br />

not just any station: a lightweight, high tech station. Using new,<br />

green, technologies like we do in our expeditions. Let’s show the<br />

world what we can do!”<br />

I stayed silent. I did not want to hurt his feelings. The man, clearly,<br />

was nuts.<br />

I had first met Alain in October 1996 at a press conference on the<br />

Mýrdalsjökull glacier, before he and Dixie Dansercoer succeeded in<br />

an unassisted crossing of Antarctica from coast to coast by skis,<br />

travelling 3940 kilometres in 100 days. In 2004, the Belgian<br />

government announced the building of a new polar base in close<br />

collaboration with a private foundation led by Alain Hubert. And<br />

so, Alain Hubert’s dream on that Icelandic glacier became a reality.<br />

In January 2007 I travelled with Alain to Antarctica to film the spot<br />

where the new Belgian Polar base was to be build: on a rocky ledge<br />

of a nunatak called Utsteinen in the foothills of the Sör Rondane<br />

Mountains. I was part of a small expedition of 12 people, living on<br />

the ice for 5 weeks, sleeping in tents, cut off from the rest of the<br />

world. I enjoyed every second of it.<br />

In 2013, I got a call from Alain Hubert asking me if I would be<br />

willing to go back to Antarctica and work as a resident journalist at<br />

the Princess Elisabeth Station base for the coming season. I had<br />

retired from the Belgian National Television station in 2009. I never<br />

expected to get a chance to see Antarctica again. I said yes.<br />

It was an emotional moment for me when I got out of the plane and<br />

saw the striking shape of Princess Elisabeth Base glittering in the<br />

sun. Alain shook my hand and said “Welcome back at Utsteinen.” I<br />

could not answer him for the lump in my throat.<br />

23

24 Image: Jos Van Hemelricjk

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Field Trip to the Coast<br />

We set out from Princess Elisabeth station for our long-awaited trip<br />

to the coast, Alain Hubert, seismologist Denis Lombardi, Roger<br />

Radoux the schoolteacher and me, your veteran reporter. We had<br />

news that our friends on Derwael Ice Rise were doing well despite<br />

heavy snowstorms that kept them pinned in their caboose for three<br />

days. They had finished drilling the first of two 30 metre holes and<br />

were 17 metres down on the second.<br />

We were to meet with them on King Baudouin Ice shelf in a couple<br />

of days, but first we were expected at Sismo Camp, 160 kilometres<br />

North of Princess Elisabeth Station in an area known as the<br />

“grounding line.” It is the place where the glacier ice that slowly<br />

flows down from the Antarctic high plateau reaches the ocean and<br />

starts floating.<br />

It took us twelve bumpy hours on our skidoos to get there. We<br />

made a stop at Asuka, an eerie Antarctic ghost town where a<br />

Japanese station was deserted in 1994. The station itself has long<br />

disappeared under the snow, but we wondered at the sight of rows<br />

of abandoned vehicles – skidoos, bulldozers and trucks - nose<br />

diving slowly in to the ice by the weight of their engines. We were<br />

surprised to see a sledge sporting a mast and spars that bore an<br />

uncanny resemblance to a catamaran wrecked on a reef in a sea of<br />

ice. We could not linger. We had another 80 kilometres to go. It was<br />

a rough ride. “A bad year for snow,” Alain admitted, “the surface is<br />

usually a lot smoother.”<br />

Sismo Camp appeared as a black speck in the whiteness. After a<br />

while we could distinguish a row of bright coloured dots: the tents<br />

where we were to sleep. There was a snow tractor and two sledges:<br />

one with the lab-container the other was loaded with fuel tanks and<br />

a 10 foot mess container. We were welcomed by Jan Lenaerts and<br />

Christophe Berclaz.<br />

“Good to see new faces,” said Jan<br />

By Iridium satellite phone we heard that the Icecon-team had left<br />

25

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

Derwael to set up a new drilling camp on the King Baudouin Ice<br />

shelf.<br />

“When you ride on a slow moving snow tractor over this plain,”<br />

glaciologist Frank Pattyn told me later, “it sets you thinking.<br />

Baudouin Ice shelf is about the size of a country like Belgium. 400<br />

kilometres across. But this shelf holds back the ice that is contained<br />

in an area that has the surface roughly the size of Europe!”<br />

Global warming has caused important ice shelves to disintegrate in<br />

the recent past, mainly in West Antarctica. Glaciers there are<br />

speeding up at an alarming rate. This is not the case in East<br />

Antarctica yet.<br />

The King Baudouin Ice shelf is typical for this area: it flows down<br />

to the coast at a leisurely pace of a 150 metres a year. This shelf<br />

seems to be stable and healthy… or is it? We do not really know.<br />

Frank made me understand that a weakening of this seemingly rock<br />

solid chunk of frozen water would have dramatic consequences on<br />

the level of ocean waters. No wonder that scientists with different<br />

specialities concentrate on studying the King Baudouin Ice Shelf.<br />

Penguin colony revisited<br />

Two years ago Alain Hubert and Kristof Soete made headlines being<br />

the first persons to set eyes upon a colony of emperor penguins<br />

whose existence up till then was unknown.<br />

The discovery was not made by accident. Alain had been looking<br />

for them since he read an article by a scientist from the British<br />

Antarctic Survey who had studied satellite pictures showing dark<br />

spots in the area that might have been caused by penguin droppings.<br />

The colony is situated at the eastern end of the King Bauduoin Ice<br />

Shelf, a 100 kilometres from Drill Camp. Alain decided it was time<br />

to pay the Emperors a new visit. See how they were doing. I was<br />

invited to go along, together with Kristof Soete and field guide<br />

Christophe Berclaz. I was thrilled. The skidoo drive was long and<br />

tedious. The sky was overcast. But I could not care less.<br />

26

27

28

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

At 9 in the evening we arrived at a waypoint marked with a red flag<br />

on a bamboo pole: the entrance to the valley where the penguins<br />

live. This valley is entirely made of ice. It is called a rift: a<br />

disturbance in the flow of the ice shelf caused by some obstacle at<br />

the bottom. A pinnacle of rock maybe that splits the ice shelf right<br />

where it reaches the sea.<br />

The lack of sunshine made it too hard to distinguish any features in<br />

the snow. It took us more than an hour to pick out a safe way down<br />

the steep slopes of the rift. We even offloaded the extra fuel cans we<br />

brought to make our skidoos lighter for the final plunge. Then<br />

suddenly we were driving on sea ice between 30 metre high walls on<br />

our left and right formed by the broken shelf. In spite of the grey<br />

weather, it was spectacular.<br />

The rookery<br />

After two kilometres, we saw the first sign of the penguin colony: a<br />

brownish line in the distance. When we drew nearer we saw<br />

individual dots. We stopped our skidoos and then we heard the din.<br />

Hundreds, no thousands of penguin chicks where squawking,<br />

yakking and flapping their little wings vigorously as if they wanted<br />

to fly.<br />

The air was heavy with the smell of fish. We stood still and watched<br />

in awe. The chicks paid no attention to our presence. They looked<br />

cute in their brown down that made them look like they wore a fur<br />

coat. They walked about clumsily with a funny rolling gait that<br />

made me smile. There were some adults around, though not as<br />

many as I expected.<br />

“This is a nursery, Alain explained, the chicks wait here until one off<br />

their parents comes back from the sea to feed them. Male and<br />

female penguin parents take equal care of their offspring. Each<br />

couple has one chick per season. That makes it very easy to count<br />

them: for each chick, we see there are two adult emperor penguins<br />

in the colony.”<br />

We saw several chicks been fed by an adult. Was it mom or dad?<br />

29

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

Impossible to say. The chick begs for food by pushing its head<br />

against the parents’ chest. The parent then regurgitates the content<br />

of its stomach and the chick greedily gobbles it right from the<br />

parent’s throat.<br />

Alain Hubert was beaming. “I can hardly believe my eyes,” he said,<br />

“the colony has definitely grown since the last time I was here. There<br />

are some 2000 chicks in this rookery. There are five rookeries of the<br />

same size. That means we have 20,000 adult penguins in the colony.”<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

We later counted not five but six rookeries full of noisy penguin<br />

chicks. One more than there was 2 years ago, this was wonderful<br />

news.<br />

The sea leopards’ attack.<br />

By the end of the season, when the ice breaks up, these youngsters<br />

will have moulted and must be ready to go to sea and fend for<br />

themselves.<br />

“Let’s go to the edge of the ice,” said Alain, “you will see the adults<br />

queuing in a long line to take their turn to dive in to the water and<br />

go fishing.”<br />

I drove my skidoo to the sea meeting many penguins on their way<br />

to feed their kid, overtaking others that were on the way back to the<br />

sea to go fishing again. They cover large distances – the rookeries<br />

are several kilometres away from the sea – sliding on their bellies<br />

propelling themselves with their feet and steering with their wings.<br />

At the edge of the ice, I found many adults, but they were not<br />

queuing. They huddled together in a tight nervous band. It was<br />

obvious that no penguin was going for a swim today. The reason<br />

soon became clear. A large seal was patrolling the waters. Not just a<br />

seal: this was a leopard seal also called a sea leopard. This ferocious<br />

predator would catch any penguin that dove off the ice.<br />

I noticed some small heads further out at sea. There were penguins<br />

out there that wanted to get back ashore and feed their chicks. They<br />

30

would have to run the gauntlet and dodge the leopard.<br />

A field trip in Antarctica<br />

Jos Van Hemelricjk<br />

I positioned myself close to the water’s edge hoping to film their<br />

attempts. I knew the sea leopard was close, but I never expected him<br />

to do what he did next. Suddenly he threw himself upon the ice,<br />

opened his mouth and went for my leg. I jumped back startled but<br />

he kept coming after me and tried to grab me. After a couple of<br />

metres, he gave up and left me standing perplexed. This animal was<br />

huge: more than 3 metres in length weighing 300 kilos or more. I<br />

am certain that if he had caught my leg he would have dragged me<br />

into the water.<br />

“You were wearing black trousers, from the water he might have<br />

mistaken you for a penguin,” someone suggested later.<br />

All I know is that this animal wanted me for his supper. And that<br />

was a sobering thought.<br />

31

Mount Fuji versus<br />

the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

37<br />

32

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

Waking up at 6:00am in Tokyo, I honestly could not muster the<br />

excitement I should have been feeling about climbing Japan’s highest<br />

and most famous volcano. I met my father in the restaurant of the<br />

hotel for breakfast. I had a delicious bacon, capsicum and cheese<br />

omelette from an actual omelette station. I threw in a couple of<br />

warm and crusty hash browns and I was energized for anything.<br />

We were staying in a very high end hotel for the week and I<br />

absolutely loved the luxury. My past six weeks in this beautiful<br />

country was mainly spent camping or staying in places that made<br />

Harry Potter’s cupboard under the stairs look like the Savoy. I was<br />

six weeks into my solo adventure walking down Japan, from<br />

Sapporo to Osaka. My dad generously paid for this week’s<br />

accommodation while he was here to tackle the climb with me.<br />

So off we went to the Shinjuku train terminal. Two trains and a long<br />

bus journey later we arrived 2,300 metres above sea level at the Fuji<br />

Subaru Line fifth station at 12:00pm. The fifth station is the starting<br />

point for people attempting to climb the mountain, and is also a<br />

popular tourist spot for those who aren’t. The air was dry and cold,<br />

but the sun was bright and warm, the type of weather I am used to<br />

back in my home town of Melbourne, Australia.<br />

After we played tourists by looking at all the lovely wares with<br />

Mount Fuji printed on every single item, we decided to check which<br />

trail we were going on, preferably the easiest. Since it was a couple<br />

of weeks before the official climbing season, there seemed to be<br />

only one trail up and down the mountain. We didn’t care, we felt so<br />

invincible that whatever trail we went up we would conquer with<br />

ease.<br />

The trail we were climbing was called the Yoshida trail and is<br />

supposedly the easiest one to do. Around 15 minutes in, we realised<br />

that we had not been going up but instead walking down what<br />

seemed like a dirt road heading down the mountain. So, we started<br />

to wonder if we were going in the right direction. After pacing back<br />

and forth contemplating, we decided to head back just to be certain<br />

as we did not want to keep going and eventually discover we were<br />

back at the very bottom of the mountain. It was lucky we did decide<br />

33

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

on back-tracking because we were oblivious of a certain rule that<br />

stated, for obvious safety reasons, before attempting the climb each<br />

climber must register at the tourism information centre. There was a<br />

film crew there for NHK, which I suppose is the Japanese<br />

equivalent of the ABC or BBC. They filmed us talking to the guides<br />

and signing in at the centre and then we headed off again. It turned<br />

out we were going in the right direction to begin with, so it was<br />

onwards and upwards for the second time.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

We arrived 2,390 metres above sea level at the sixth station just after<br />

1:30pm. They had a toilet there so I thought it best to relieve myself<br />

while I had the chance, nothing worse than being caught with your<br />

pants down on the side of a cold icy mountainside (if you catch my<br />

drift).<br />

After the sixth station, the trail started upwards. Most of the way to<br />

the summit was on a 45-degree incline. We hiked up a dirt path<br />

surrounded by low hanging trees and shrubs until we reached a<br />

lovely little shrine and decided that this would be an ideal spot to<br />

stop and have a break. The shrine was made of wood and stone<br />

statues, at night time they would be eerily scary to an imaginative<br />

mind such as mine. We decided to try our luck at bowing to the<br />

statues in the hopes of safe travels to the top. It began to rain and<br />

shortly after, the musky scent of petrichor was in the air. The path<br />

felt like it was going on forever. I was struggling and we had to stop<br />

quite a lot to recover. The altitude was the biggest challenge for me<br />

and the temperature was dropping significantly. My dad seemed to<br />

be doing better than me and was beginning to appear as a small<br />

silhouette in the distance.<br />

We made 2,700 metres above sea level to the seventh station at<br />

around 3:30pm. From then on the trail up transformed from a dirt<br />

and loose gravel path to rocks, boulders, snow and ice. We bought<br />

some more water from one of the resting huts.<br />

The struggle, the cold and the slight altitude sickness was worth it,<br />

thanks to the greatest view you could possibly see anywhere in<br />

Japan. It was amazing, particularly when the clouds cleared and I<br />

could look down at the impossibly green trees. It gave me the<br />

34

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

motivational boost I was searching for. As we were climbing the<br />

steep rocky path, two young British guys were coming up behind<br />

us. They were in T-shirts and shorts and a light backpack. We<br />

started chatting and discovered that they chose to climb the<br />

mountain after they saw Karl Pilkington attempt it on An Idiot<br />

Abroad. They had not booked a hut to stay in and were hoping they<br />

could pay with their credit card as they did not have any cash with<br />

them. They essentially just decided, “Hey! Let’s climb Mount Fuji<br />

today.”<br />

At around 6pm we arrived at another hut. Luckily for the two Brits,<br />

the owners of the hut accepted their card, so to be safe they chose to<br />

stay there for the night, to avoid the risk of climbing a couple of<br />

hours further to a hut that might not and thus be forced to make the<br />

climb back down again. They also wanted time to have a few beers<br />

and a decent sleep to make it to the top before sunrise the next<br />

morning.<br />

For us though, we had not reached our Hut and it was getting late,<br />

we did not expect to be climbing for this long, as we believed that<br />

the trek would only take six to seven hours to reach the summit, we<br />

had been climbing longer than that already and we were not even at<br />

the hut we booked for the night.<br />

We also did not expect it to be this difficult. We assumed that given<br />

the height we were at and the hours we had already climbed, that we<br />

must be close. We had to make it before dark, so we pushed on. At<br />

around 7:15pm we saw what appeared to be lights up above. I could<br />

barely walk and I felt like I was coming down with vertigo. If it was<br />

not the hut we booked, I was going to collapse there anyway and<br />

call it a day. Luckily, it was.<br />

We stepped inside the communal hall. It had three long, wooden<br />

tables, two of which were full of seated Japanese men and a couple<br />

of women. The smell of the room reminded me of an old high<br />

school gym changing room, but it was warm and comfortable<br />

nonetheless. The owners were extremely welcoming and brought us<br />

to the empty table, sat us down and gave us a hot meal and some hot<br />

tea. It was the best meal I have ever tasted, even better than the<br />

35

36

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

omelette from breakfast that felt like an eternity ago. It appeared to<br />

be some kind of meat with cold sticky rice and spices, but to me it<br />

tasted like salt and pepper calamari, hot chips and tartar sauce. I<br />

must have been delusional.<br />

After the meal we were escorted to the next room and shown the<br />

bunks where we would sleep. It was a large ‘L’ shaped room with<br />

mattresses along the floor and another wooden level with the same<br />

set up. There were no lights so we put our bags down and tried to<br />

get some warmer clothes on and went to bed. Sleeping was difficult<br />

as the temperature dropped just below zero and there was no<br />

heating. At around 9:00pm I needed to go to the toilet, so I rolled<br />

off the bunk and headed outside. I had to make sure to take 200 yen<br />

and my torch, the last thing I wanted was to walk off the cliff that<br />

the hut was residing on.<br />

Some hours later, we were woken up by a member of staff, violently<br />

shaking our legs to wake us up. I looked at my watch and saw the<br />

short hand on the three, I wanted to die. My chest felt like a sumo<br />

wrestler was sitting on me, and my head felt like an empty<br />

toothpaste tube being squeezed for its last drop of oral sanitary<br />

goodness. We shuffled into the communal hall and had some cold<br />

rice for breakfast. I felt like shite! I was shivering to my bones and I<br />

had altitude sickness, I did not think I could climb another 200<br />

metres to the summit. We left the hut at 3:30am and started our<br />

journey up once more. It was incredibly dark, so our head torches<br />

were a necessity, although all we could see was the frost in the air.<br />

The sub-zero night had caused an already rocky climb to change to<br />

a dangerously cold, icy path. A lot of the locals recommended us to<br />

have spikes on our boots, but as we did not have any, we had to<br />

disregard their concerns.<br />

We finished the 3,776.24 metres above sea level climb to the summit<br />

just before 5am. The sun rose about 15 minutes prior but that did<br />

not matter, the view was spectacular! Even though my body felt like<br />

it was shutting down whilst simultaneously imploding, the scenery<br />

and feeling of accomplishment was more than worth it. I was soon<br />

jumping around with excitement in no time. We walked around the<br />

summit and peered into the abyss of the volcano. The depth of it<br />

37

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

was astounding. I would not have liked to be around when that<br />

behemoth erupted.<br />

After spending enough time soaking in the scenery, we began our<br />

descent just after 6:00am. There was supposedly an easier, faster<br />

path to get back down but unfortunately, as I previously mentioned,<br />

the season had not officially started so it was still closed off. We had<br />

no choice but to head back the way we had come. Along the way<br />

down, we noticed that now the sun was shining bright, it was<br />

melting the ice and snow on the rocks, which in turn caused it to be<br />

more like a slip and slide minus the fun. It was also making the path<br />

longer to get down. Suddenly, the telescopic walking poles I was<br />

using for support collapsed in on themselves and I fell a metre down<br />

onto my back. I cursed and swore at the heavens due to the pain,<br />

but mostly the frustration in myself for not preparing more before<br />

attempting to tackle this mountain.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

After that we decided it best to take a break. The clouds were below<br />

us, so we could not see how far we had to go, which made the trek<br />

feel like an eternity. The further down we went the easier it was to<br />

breathe, but with the constant downward climb and balancing on<br />

rocks, the pressure was taking its toll on our feet, ankles and knees.<br />

I must have rolled my ankle about fifty times. Every time we<br />

reached a hut we were certain we must be past the rocks and as far<br />

as the dirt path, but we weren’t. We also seemed to be going slower<br />

than the other climbers coming down the mountain. The workers<br />

were climbing down like mountain goats. They would casually<br />

jump down from one icy rock to another like a child playing<br />

hopscotch. I hated them for that!<br />

It was around 1:30pm and we were back at the seventh station. An<br />

American family were having lunch. There were about fifteen of<br />

them, loud and talking over each other. It reminded me of my<br />

family at Christmas, or any of my family affairs for that matter. The<br />

Japanese people who were guiding them, were too polite to say<br />

something but we could tell they were getting annoyed with them.<br />

Sometime after that we finally made it to the dirt path again. We still<br />

had a long way to go and needed to be back at the fifth station soon.<br />

The last bus off the mountain to get us on our way back to Tokyo<br />

38

Mount Fuji versus the couch potato<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

was leaving at 3:30pm, if we did not make it on time then we would<br />

be stuck up there another night. It felt like the closer we were to the<br />

finish, the slower and slower we became, but we were determined to<br />

make it.<br />

Our feet were sore and my knees were cracking at every step. My<br />

dad was beginning to worry me as he tripped and injured his foot.<br />

He was in pain for the rest of the way down and after I returned<br />

back to Australia nine weeks later, I realised one of his toes was still<br />

black from the fall.<br />

We finally arrived at the fifth station at 3pm looking like a defeated<br />

Harry and Marv from Home Alone. Our legs had turned to<br />

gelatine. We hobbled into the tourist information centre to let them<br />

know we were back, and to collect our stamp of completion. The<br />

film crew were still there. When they saw us they began filming<br />

again. They requested if we would like to act out scenes looking at<br />

maps and brochures and interviewed us on what we are doing in<br />

Japan. So, I mustered the best of my acting skills that I acquired<br />

from high drama and delivered an Oscar-worthy performance. A<br />

few weeks later I contacted NHK to try to obtain some of the<br />

footage but due to the large amount of shows and channels they<br />

have, they could not locate it without a name for the program,<br />

which I forgot to write down.<br />

We made it just in time to get on the bus. There was only one seat<br />

left which I let my dad have due to his injured foot, and because I’m<br />

just such a good son. It was the longest bus ride I have ever been on.<br />

We finally made it back to our hotel at 7:30pm, went to our rooms<br />

and collapsed on the bed. I woke up twelve hours later with all my<br />

clothes on, and one shoe.<br />

It was the toughest and most rewarding experience I have ever<br />

embarked on, both physically and mentally. There were many times<br />

when I did not think I was going to make it, many times when all I<br />

wanted to do was give up and go home. The one thing I know for<br />

sure is that I would not have made it to the summit on my own<br />

without the help of my constantly positive and supportive father.<br />

Thanks, dad!<br />

39

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

40

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

“The most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or touched,<br />

they are felt with the heart.” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit<br />

Prince<br />

Glancing out the window of the Midnight Express train to<br />

Marrakesh, I watch the mysterious shadows dance across the night<br />

sky, and the flickering village lights pass by. There is the distinct<br />

smell of jasmine and paper fires in the air. I am traveling with Tor, a<br />

man I recently connected with, after 25 years. It is my first time in<br />

Morocco, a place I have dreamed of visiting since I was a child. We<br />

drink gin and tonics and stand in the aisle getting a little too<br />

amorous for the Moroccan conductor.<br />

“Excuse me, but if you two can’t keep your hands off each other, go<br />

to your compartment!” He tells us in gruff French. We feel like<br />

teenagers.<br />

In the morning, as the sun rises over the pink city of Marrakesh, we<br />

meander our way from the train station to our riad in the old Jewish<br />

quarter. The passageways are narrow and confusing, young children<br />

kick balls and old, wizened women stare at us from doorways.<br />

Alleyway stalls sell spices, apricots, dates and colorful carpets,<br />

Arabian night-like lamps, leather goods and ceramic tagines. The<br />

spices temporarily transport me back to my life in Madagascar. In<br />

the Djemaa el-fna square we watch snake charmers, boxing matches,<br />

ornately dressed men selling water from their goatskin bags, epic<br />

storytellers, a blind violinist, colorfully robed women and old men<br />

in djellabas mumbling “Allah” over and over mantra-like. Tor<br />

recommends I try a traditional bath.<br />

Curious, I wander alone to a hammam, tucked down a narrow<br />

corridor among merchants selling their wares. I pay 64 dinars to a<br />

skinny middle-aged man who waves me to the female section.<br />

Recently divorced, starting out on a new life path, I feel in need of a<br />

good cleansing.<br />

A short, bow-legged woman, simply wearing black underwear,<br />

takes me by the hand and leads me into a warm cement room. Her<br />

41

42

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

large breasts sag down to her stomach. She gives me the once over<br />

and seems slightly perturbed that she has to deal with me.<br />

Another older woman, who wears a headscarf and gray djellaba,<br />

smiles at me. She is missing a tooth and gestures for me to sit down<br />

on a long narrow bench. The women do not speak English or<br />

French; I do not speak Arabic or Berber, so we communicate by<br />

hand signals and eye gestures.<br />

The clothed woman beckons for me to disrobe. I take off my lightgreen<br />

djellaba which I had purchased earlier as I wanted to try to<br />

blend in to the culture. Tor thinks my mysterious dark eyes won’t<br />

give me away.<br />

I carefully place my money and watch in the hood and she knots it<br />

for safekeeping. I lay my t-shirt, bra and sandals in a pile on the<br />

bench. I soon realize that women wear pajama-like pants under<br />

their djellabas. They probably think I am strange because I am<br />

naked underneath. I hope they don’t think I am a loose European.<br />

From Marrakesh we head south to the snow-capped mountains,<br />

which tease us on our way to Mount Toubkal, the tallest mountain<br />

in North Africa, at 4167 metres. We meet up with our two<br />

American friends and Karim who will handle our logistics for the<br />

journey.<br />

“Salaam alaikum.” He greets me with his hand over his heart. Tor<br />

calls him Dom, for Dom DeLuise, as he looks and laughs like him.<br />

Tor’s acquaintance, Karim, is shaped like a bowling ball, has an<br />

infectious smile, and is a bit of a raconteur. Years ago, he stowed<br />

away on a ship bound for New York City with ten dollars, and a<br />

slip of paper with a phone number on it. Through a combination of<br />

hard work and street savvy, he had worked his way up from a dish<br />

washer to a used car salesman in Seattle.<br />

“My first day I knew nothing about cars, and when my first<br />

customer asked my advice concerning one of the cars on the lot I had<br />

to be honest with her. I told her I had never sold a car in my life,<br />

43

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

only donkeys, for my father. The lady bought a car, my first sale, and<br />

after that I told everyone the same donkey story.”<br />

His rotund belly shakes as he explodes in laughter. Karim is<br />

likeable, in a raffish kind of way, and I can tell he is faithful to his<br />

family and friends. Tor likes Karim, yet, keeps a close eye on him<br />

and corrects him when he embellishes the history of Morocco or the<br />

Koran. This seems to trouble Karim, as a large part of his success as<br />

a tour guide, is based on his authoritative persona. Karim is a driven<br />

man with his sights set on success. The thing I like best about Karim<br />

is that he makes me laugh.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The olive and orange trees are replaced by apple and walnut trees as<br />

we travel up into the mountains. It starts to rain lightly and there is<br />

a wonderful fragrance in the air. Imlil is the gateway town for our<br />

ascent of Mount Toubkal.<br />

Mud houses on the upper reaches of the village remind me of my<br />

visit to the Himalaya the previous year and I am told the movie<br />

Seven Years in Tibet was filmed here. When I saw the movie many<br />

years ago, I thought of Tor, even though I hadn’t seen him in over<br />

twelve years then. Brad Pitt’s character, Heinrich Harrer, reminded<br />

me of Tor, with his toughness, adventurous spirit, interest in<br />

Buddhism and the Himalaya Mountains. Even Pitt’s looks, such as<br />

his thick lower lip and sandy blonde hair reminded me of Tor. Tor is<br />

a tall burly man with crystal blue eyes, wide nose and gapped teeth<br />

(he would cringe if he read this).<br />

This is Karim’s first time on a major climb and he is a little nervous.<br />

He wears a used backpack he purchased in Seattle, hiking books<br />

from Tor, and a pair of trekking poles borrowed from a local guide<br />

in Imlil. Karim is certainly geared up, yet does not fit the image of a<br />

mountain climber. I notice Tor eyeing him up and down with a<br />

smirk on his face. “Off we go in to the wild blue yonder, off we go in<br />

to the sky.” Tor sings his mountain mantra and sets off at his usual<br />

fast pace.<br />

In the morning the five of us hike up the trail, which begins as a dirt<br />

road. I wear my silk hiking skirt and I feel a kinship with Karim as<br />

44

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

we both wear floppy looking hats to keep the sun off our faces (I<br />

have noticed Tim Cahill, adventure extraordinaire wears a similar<br />

hat). Tor, hatless, makes fun of our practical sunhats. We see a few<br />

European trekkers on the trail and all the women wear pants. I<br />

prefer to wear a skirt in more traditional societies and it is easier to<br />

be more discrete when I have to pee in the bush.<br />

Trail-side stands sell rocks, fossils, carpets and ceramics. A glimmer<br />

of white snow sparkles high in the mountains. The lower elevations<br />

are lush with trees, however, as we climb higher and leave the river<br />

valley the landscape is dry and desolate.<br />

We encounter donkeys with overloaded baskets, weighing heavy on<br />

their bodies, and carrying a robe clad person side-saddle. The wide<br />

river slowly narrows and we cross it into a small village. A twostory<br />

high white painted boulder sits beside a pink minaret.<br />

“Why is that painted white Karim?”<br />

“A man died here and now a holy man lives here.” He seems afraid<br />

and says the holy man is evil.<br />

I presume he is a medicine man as Karim tells us he uses healing<br />

herbs.<br />

Maybe there is a curse; soon thereafter I look back down the trail,<br />

and I wonder where our friends are. Tor, Karim and I stop to wait<br />

for them. Ten minutes later our friend comes up to tell us her<br />

husband is vomiting. We are not sure if it is the altitude or the food<br />

we have been eating. Tor has been moving extremely fast and not<br />

considering the elevation gain.<br />

“Siffy, you and Karim keep going up. I am going to make sure they<br />

find a place to stay and are ok. I will catch up.”<br />

I lead Karim up the steep slope. He is doing well for his first foray<br />

into the mountains, but he is tired.<br />

“Oh an orange juice stand! Let’s stop!” I want to keep going, but I<br />

45

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

comply.<br />

We drink our juice while a tired donkey guzzles water from a barrel.<br />

The mountains are now cloaked in clouds, but we can see down the<br />

rock strewn valley beneath us. A herd of goats grazes among the<br />

rocks. I smell tea and again Karim wants to stop.<br />

“Karim, that looks like Tor down there!”<br />

Tor quickly approaches and is grateful to have a break.<br />

“I found a basic room and the locals will take good care of them.”<br />

Less than an hour later we arrive at the refuge les Mouflons de<br />

Toubkal. Visions of Count Dracula’s castle come to mind, especially,<br />

in the low lying clouds. There are no windows inside this stone<br />

building which adds to the effect. I realize we are at 10,521 feet, so<br />

will have over 3000 feet to climb the next day to the peak.<br />

Several men work at the hut and serve us a tagine and vegetables for<br />

dinner. Tor and I sit next to a sweet young Czech couple who<br />

practice their English with us. Karim, always gregarious, chats with<br />

the Moroccan alpine guides while pouring over maps.<br />

After breakfast we trudge up the trail and collectively move up the<br />

mountain. Two hours later and we are second guessing our route;<br />

Karim speaks with several men traveling with donkeys and asks<br />

about the trail route.<br />

We are on the wrong trail!<br />

I reflect on the many paths in life and how I had followed the<br />

wrong route, or so I felt, so many times. But what is a wrong path?<br />

It was the way I took, so it must have been the correct route, I<br />

muse. All I know is that Tor and I are finally together, after several<br />

failed attempts to connect over the years, and I am on the correct<br />

path now.<br />

46

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Hammam<br />

Siffy Torkildson<br />

Tor, Karim and I return to the hut at 10 a.m., a two hour detour. We<br />

are all a little discouraged, but we decide to keep pursuing Mount<br />

Toubkal. It is windy and cold and I am thankful for my many layers<br />