Ripcord Adventure Journal 2.4

Our final issue of volume 2 is quite a mixture of adventure and exploration of the world's polar regions, deserts, oceans, mountains and jungles. In our Guest Editorial, Leon McCarron ventures in to the hills of Jordan as part of his 1000-mile journey on foot, across the Middle East, when he encounters an unexpected musical interlude on a lonely hillside. Planning is essential for major expeditions, even more important to have several back-up plans in case the first one or two, or three do not pan out as expected. Mark Wood brings us behind the scenes of planning for a polar expedition. Technology in the classroom has been touted for more than 2 decades as the next big thing. Here, Joe Grabowski, whose nascent organisation "Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants" has demonstrated that indeed technology can be the medium by which exposure to new and exciting educational contexts can be brought in to the classroom from the real-life connections with explorers, conservationists and scientists in the field. Former Marine Commando, John Sullivan gives us an introduction to what it takes to survive in the desert using the skills and experience he has built up from his time in the forces, leading expeditions and working with film crews on location. What does it take to circumnavigate the globe on one's own, what drives an adventurer to take on and complete such demanding challenges? Erden Eruc takes us with him on his life's journey across oceans and continents. Finally, we catch up with emergency medical doctor Claire Grogan and Mark Hannaford of World Extreme Medicine to discuss the fast-paced world of extreme medicine.

Our final issue of volume 2 is quite a mixture of adventure and exploration of the world's polar regions, deserts, oceans, mountains and jungles.

In our Guest Editorial, Leon McCarron ventures in to the hills of Jordan as part of his 1000-mile journey on foot, across the Middle East, when he encounters an unexpected musical interlude on a lonely hillside.

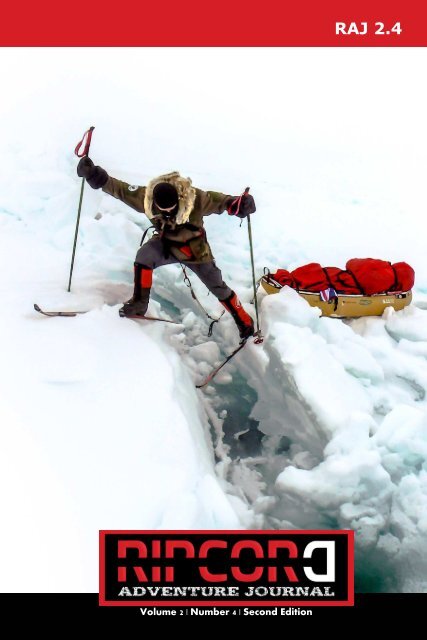

Planning is essential for major expeditions, even more important to have several back-up plans in case the first one or two, or three do not pan out as expected. Mark Wood brings us behind the scenes of planning for a polar expedition.

Technology in the classroom has been touted for more than 2 decades as the next big thing. Here, Joe Grabowski, whose nascent organisation "Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants" has demonstrated that indeed technology can be the medium by which exposure to new and exciting educational contexts can be brought in to the classroom from the real-life connections with explorers, conservationists and scientists in the field.

Former Marine Commando, John Sullivan gives us an introduction to what it takes to survive in the desert using the skills and experience he has built up from his time in the forces, leading expeditions and working with film crews on location.

What does it take to circumnavigate the globe on one's own, what drives an adventurer to take on and complete such demanding challenges? Erden Eruc takes us with him on his life's journey across oceans and continents.

Finally, we catch up with emergency medical doctor Claire Grogan and Mark Hannaford of World Extreme Medicine to discuss the fast-paced world of extreme medicine.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 2 | Number 4 | Second Edition<br />

RAJ <strong>2.4</strong>

A Letter from the Editor<br />

Welcome to <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

Our final issue of volume 2 is quite a mixture of adventure and<br />

exploration of the world's polar regions, deserts, oceans, mountains<br />

and jungles.<br />

In our Guest Editorial, Leon McCarron ventures in to the hills of<br />

Jordan as part of his 1000-mile journey on foot, across the Middle<br />

East, when he encounters an unexpected musical interlude on a<br />

lonely hillside.<br />

Planning is essential for major expeditions, even more important to<br />

have several back-up plans in case the first one or two, or three do<br />

not pan out as expected. Mark Wood brings us behind the scenes of<br />

planning for a polar expedition.<br />

Technology in the classroom has been touted for more than 2<br />

decades as the next big thing. Here, Joe Grabowski, whose nascent<br />

organization "Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants" has<br />

demonstrated that indeed technology can be the medium by which<br />

exposure to new and exciting educational contexts can be brought in<br />

to the classroom from the real-life connections with explorers,<br />

conservationists and scientists in the field.<br />

Former Marine Commando, John Sullivan gives us an introduction<br />

to what it takes to survive in the desert using the skills and<br />

experience he has built up from his time in the forces, leading<br />

expeditions and working with film crews on location.<br />

What does it take to circumnavigate the globe on one's own, what<br />

drives an adventurer to take on and complete such demanding<br />

challenges? Erden Eruc takes us with him on his life's journey<br />

across oceans and continents.<br />

Finally for this isue, we catch up with emergency medical doctor<br />

Claire Grogan and Mark Hannaford of World Extreme Medicine to<br />

discuss the fast-paced world of extreme medicine.<br />

We aim to be the home of authentic, adventurous travel, which<br />

serves as a starting point for personal reflection, study and new<br />

journeys. We hope you enjoy reading this free digital <strong>Journal</strong> and<br />

encourage you to share it it widely.

On behalf of the editorial, writing and design team, I wish to<br />

acknowledge our sponsors, the World Explorers Bureau and<br />

Redpoint Resolutions (Mark Cohon, Thomas Bochnowski, Ted<br />

Muhlner, Martha Marin, John Moretti and all the team).<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

Editor in Chief, <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

www.ripcordadventurejournal.com<br />

www.ripcordtravelprotection.com<br />

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Copyright June 2017 by Redpoint Resolutions &<br />

World Explorers Bureau.<br />

Assistant Editor: Méabh Lavery<br />

All articles and images © 2017 of the respective Authors.<br />

Cover image © Mark Woods. Inside Cover image © Leon McCarron.<br />

Second Edition © 2017<br />

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> has been typeset in 11 point Garamond and uses US<br />

English spelling.<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed,<br />

or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording,<br />

or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission<br />

of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical<br />

reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.<br />

Although the publisher has made every effort to ensure that the information in<br />

this book was correct at press time, the authors and publisher do not assume and<br />

hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption<br />

caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from<br />

negligence, accident, or any other cause.<br />

For permission requests, general enquiries or sponsorship opportunities, contact<br />

the publisher: info@ripcordadventurejournal.com

"The very basic core of a man's living<br />

spirit is his passion for adventure. The<br />

joy of life comes from our encounters<br />

with new experiences, and hence there<br />

is no greater joy than to have an<br />

endlessly changing horizon, for each<br />

day to have a new and different sun."<br />

Jon Krakauer<br />

"Into the Wild"

RIPCORD<br />

ADVENTURE<br />

JOURNAL<br />

<strong>2.4</strong><br />

Editor<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

Assistant Editor<br />

Meabh Lavery<br />

Featuring<br />

Leon McCarron<br />

Mark Wood<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

John Sullivan<br />

Erden Eruc<br />

Claire Grogan<br />

Mark Hannaford<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

Paul Devaney<br />

Dr Terry Sharrer<br />

Charlotte Baker-<br />

Weinert<br />

Bill Steele<br />

James Borrell<br />

Publishers<br />

World Explorers<br />

Bureau & Redpoint<br />

Resolutions<br />

WWW.RIPCORDADVENTUREJOURNAL.COM

Contents<br />

Lone Piper of the Jordan Hills<br />

Leon McCarron<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

How to Survive in the Desert<br />

John Sullivan<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruc<br />

Expedition Medicine<br />

Claire Grogan & Mark Hannaford<br />

Contributors and credits<br />

3<br />

7<br />

19<br />

25<br />

31<br />

57<br />

62<br />

Image opposite © Leon McCarron<br />

In the Jordan Hills<br />

1

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Lone Piper<br />

of the<br />

Jordan Hills<br />

2<br />

Leon McCarron<br />

Text & Images © Leon McCarron

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Lone Piper of the Jordan Hills<br />

Leon McCarron<br />

I’m lost in my own head. It’s been nearly two days since I<br />

saw another human. I’ve taken to watching beetles when I<br />

stop walking. London feels a long way away.<br />

Hours pass and I don’t notice. Things that impact upon me:<br />

hunger, heat, noise. Those three things are the only way into<br />

my world.<br />

Suddenly the valley walls around me begin to sing. I wonder<br />

if I have finally gone crazy. Birds scatter from the crevices in<br />

the sandstone; one rock looks like a human skull, and the<br />

flying beasts emerging out of it are disconcerting. The sound<br />

though is beautiful - a human voice projecting out from the<br />

natural theatre of stone. Then an instrumental break; a flute<br />

solo. A chirpy tune starts up, high notes trilling their way<br />

back down the valley. I’ve lost interest in beetles now.<br />

On the hilltop, I see a figure; at first a silhouette, then<br />

features. It is a young man, sitting side-saddle on a donkey.<br />

To the left side of his face he holds a metal tube and his eyes<br />

are closed as he concentrates. This is the source of my<br />

wilderness concert.<br />

The pace of the shepherd is slow. He plays his own<br />

soundtrack as he rides towards me, a Biblical flock of goats<br />

leading the vanguard. With the timing of a true professional,<br />

he finishes his tune and jumps off to shake my hand. I tell<br />

him in bad Arabic that his playing was beautiful. He<br />

sidesteps the compliment. It all comes from the shababa, he<br />

says - his instrument. We drink tea and he plays some more. I<br />

try; I used to play the tin whistle pretty well. I try an Irish jig<br />

on the shababa and embarrass myself. More tea is poured to<br />

cover over the moment.<br />

The pot empties and the piper leaves. I forgot to ask his<br />

3

Lone Piper of the Jordan Hills<br />

Leon McCarron<br />

name. He jumps back aside his donkey and begins to sing<br />

once more. A few minutes pass and he’s gone, over the far<br />

hillside. The echoes of his song slowly leave the valley in his<br />

wake.<br />

I’m back where I was. Back to the beetles, and onwards<br />

down the valley.<br />

This short story is taken from Leon McCarron's 1000 mile walk<br />

through the Middle East, from Jerusalem to Mount Sinai. A book –<br />

The Land Beyond: 1000 miles on foot through the heart of the<br />

Middle East – will be published in late September.<br />

4

"A traveler is really not someone who<br />

crosses ground so much as someone who<br />

is always hungry for the next challenge<br />

and adventure."<br />

Pico Iyer<br />

Interviewed in the Smithsonian.com<br />

5

Plan D<br />

6<br />

Mark<br />

Wood<br />

Text & Images © Mark Woods

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

My initial thought for this assignment was that I could write<br />

about my next expedition which is happening in 2018 but to<br />

state the obvious, it hasn’t happened yet. It’s very easy to talk<br />

about a journey but a lot harder to make it happen.<br />

If I had lived during the days of the great pioneers of ice<br />

exploration, then, if I was lucky, I would have been one of<br />

the men scrubbing the decks of the Endurance or Discovery.<br />

In this modern era of exploration if you have the desire to<br />

explore, the opportunities are far greater.<br />

In most countries, anyone can be an “adventurer” – there are<br />

enough professional guiding companies to help support your<br />

dreams. There are also a few individuals like myself, who like<br />

to take these journeys a step further, by exploring on our<br />

own terms - if you have the experience, the time and funding<br />

then these kinds of adventures are possible.<br />

In the Golden Age of polar exploration, if anything went<br />

wrong on the expedition, the emphasis was very much on<br />

themselves and self-sufficiency – rescue could be months,<br />

even years away, if at all. However, nowadays it’s very<br />

different. We must acknowledge, that there exists a real<br />

responsibility to the rescue teams who could potentially risk<br />

their own lives to extract failed expedition teams from the ice<br />

and bring them home safely.<br />

Global warming is having a profound effect on how and<br />

where we explore – my journeys are about heading into these<br />

fragile, cold areas of our planet, to film the reality of what we<br />

are moving through. I connect with schools around the<br />

world to communicate the issues we face with changing<br />

climate and as a non-scientist myself, I link-up with climate<br />

experts to verify and explain what we have seen. It’s a new<br />

way to explore but we are governed by the ice and by the<br />

7

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

rescue teams who have the final say on whether we can<br />

operate or not.<br />

In 2016, I came back from the North Geographic Pole –<br />

physically exhausted and mentally battered. Our team sat<br />

together and made a documentary called A Race Against<br />

Time, based on what had just happened. For the first time<br />

ever, the expedition was almost two thirds of the way in even<br />

before we had set foot on ice. The instability of the arctic ice<br />

prevented our team from even setting out on the journey.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

One of our team members Paul “Vic” Vicary looked at the<br />

chaos we had just got back from and commented, that based<br />

on our initial mission statement we went from Plan A to Plan<br />

D.<br />

Expedition name: A Race Against Time<br />

Team members: Mark Wood, Paul “Vic” Vicary, Mark<br />

Langridge<br />

Mission Statement: “To film the harsh honest reality of how<br />

global warming has affected the Arctic Ocean through the<br />

eyes of modern day polar explorers.”<br />

Outline: Over the past two years we have liaised with<br />

logistics’ teams from the Canadian and Russian Arctic to find<br />

a suitable starting point along the edge of the Arctic Ocean.<br />

This has proven to be extremely difficult.<br />

The following report is based on the original mission<br />

statement of the expedition and is a detailed breakdown of<br />

events leading up to the expedition. The reason for this<br />

detailed analysis is to show how modern-day exploration is<br />

determined not only by sponsorship and the skill of the team<br />

8

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

but also by the commitment of support teams that pledge<br />

their lives to this environmentally sensitive and dangerous<br />

region of our planet. It is a direct reflection on how global<br />

warming is now affecting polar travel.<br />

Post expedition analysis by Mark Wood<br />

Plan A<br />

Canada - first approach<br />

After years of inserting and extracting teams on the ocean, in<br />

2015, the Canadian logistic operators Ken Borak Air (KBA)<br />

stopped all flights for the 2015/16 seasons. This was mainly<br />

down to two reasons which parallel each other. The first was<br />

the unpredictability of the ice, making it difficult for their<br />

Twin Otter planes to judge a strong landing point; the second<br />

reason, was that some of their new pilots did not have<br />

enough experience landing on sea ice, especially above 87<br />

degrees north. This is roughly 180 Nautical miles from the<br />

North Pole and over 300 NM from the Canadian coastline.<br />

Once a team passes 87 degrees, heading North to the pole,<br />

KBA would require 2 planes to support each other just in<br />

case one fails.<br />

Each member of team has had military and rescue experience<br />

so we understood KBA's concerns and respected their<br />

decision.<br />

Plan B<br />

Russia - second approach<br />

We then took the expedition to the Russian logistic team<br />

VICAAR - historically the main problem with starting from<br />

their coastline was that satellite images would show up to 40<br />

NM of open water. This would mean a drop off on ice and if<br />

9

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

possible we wanted to avoid this. It is generally recognized<br />

that within the polar world a coastal starting point to the<br />

North or South Poles or even areas such as Greenland would<br />

be recognized within the historical stats.<br />

We are not glory hunters or flag wavers but if we were to<br />

commit to a tough, long-range journey across the Arctic<br />

Ocean, this would be our preferred option. The good news<br />

was that eight months prior to the expedition we had<br />

sanctioned a drop-off of aviation fuel along the coastline to<br />

support our own insertion when it would happen.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

During the flight the pilots reported the ice was solid and<br />

safe to land on - which meant a coastal start was possible, but<br />

we would need to set off at the end of winter to ensure solid<br />

ice, operating in temperatures below -40 C. The ice status<br />

was verified by VICAAR just weeks before our due<br />

departure date.<br />

During our pre-expedition planning with VICAAR we had<br />

many hours of emails and phone calls arranging contracts<br />

and trying to deal with a lot of red tape. One problem was<br />

obtaining the required Russian visas, so we recruited a<br />

private company in London to support our team members in<br />

processing them quickly. This was achieved and up to 4<br />

weeks before departure the expedition had a green light.<br />

I then received an email from VICAAR informing me that<br />

the group visa had been refused and as it was a government<br />

decision we didn't receive a reason and we were not able to<br />

contest it - even though we tried, twice!<br />

We can only speculate about British and Russian political<br />

issues at the time but in reality, we were left in the dark. As<br />

this report will outline there was a mass military exercise<br />

10

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

with over 100 armed Russian paratroopers at the North Pole<br />

when we eventually headed out. The timing of this was too<br />

coincidental to not rule it out as one of the reasons they<br />

didn't want a British team skiing through the middle of a<br />

military operation. However, this is just speculation.<br />

Plan C<br />

North Pole reversed<br />

Our motto for the expedition was “Always a Little Further”<br />

and our mission statement as stated above outlined our belief<br />

in the journey. We spoke to the VICAAR to see if they<br />

would support a drop off via helicopter at the Geographic<br />

North Pole to attempt a reversed expedition to the coast line<br />

of Canada. They agreed to do this and also stated that their<br />

rescue support would only extend to 87 degrees north from<br />

the North Pole.<br />

Our next obstacle was to go back to the Canadian logistics<br />

team at Ken Borek Air, to request support for a possible<br />

rescue from 87 degrees North to the coast line. To do this, I<br />

felt we needed someone in the exploration world to vouch<br />

for our experience and professionalism.<br />

At the time that we were evaluating how best to persuade the<br />

Canadians that we needed their support, we received some<br />

devastating news. Our expedition Patron, Lieutenant<br />

Colonel Henry Worsley had died on the 24th January 2016<br />

while attempting to complete the first solo and unaided<br />

crossing of the Antarctic.<br />

Henry was a British Army officer and a friend of the team. In<br />

fact, Vic, Mark and I had been on Henry’s previous<br />

expedition to the South Pole in 2010, a century after the race<br />

to the South Pole that gripped the world, we had attempted<br />

11

12

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

to retrace the steps of Scott and Amundsen.<br />

The day his death was announced I was invited to appear on<br />

BBC Newsnight to talk about Henry and the dangers of<br />

exploration. The following day I was contacted by Steve<br />

Jones who was the Antarctic Logistics Base camp manager<br />

and had been supporting Henry.<br />

I shared our challenge with Steve and he also knew of our<br />

expeditions over the years in both the Arctic and Antarctic<br />

circles. Steve knew the team at KBA and immediately agreed<br />

to help and put forward our request.<br />

KBA agreed, which was remarkable in a year in which they<br />

had closed their doors on a lot of expeditions. As their<br />

commitment was below 87 degrees this would mean they<br />

would only have to use one plane to organize a pick-up. So,<br />

the expedition was back on.<br />

Svalbard - Longyearbyen.<br />

We left London Heathrow with 6 sledges and 29 pieces of<br />

luggage on the 23rd March 2016. The team trained from a<br />

small town called Longyearbyen on the island of Svalbard –<br />

an archipelago in northern Norway. Constituting the<br />

westernmost bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic<br />

Ocean, the Norwegian Sea, and the Greenland Sea.<br />

We had arrived early in the season to be inserted into the<br />

North Pole which would give us the valuable time we needed<br />

to cross the Arctic Ocean. After a week of preparation which<br />

consisted of testing equipment and going over routines on<br />

the nearby glacier - we awaited confirmation of our<br />

departure to a temporary Russian ice station called Camp<br />

Barneo. Our agreement was that we would be dropped off<br />

13

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

on the first technical flight - the first flight sets up the 800<br />

meter runway on the ocean and the second flight (potentially<br />

our flight) brings in the rest of the ground crew.<br />

The drop off date we were given by the Russians was the 1st<br />

April and the Canadians made it abundantly clear that their<br />

last pick up on sea ice would be the 5th of May with some<br />

leeway if we were progressing well to the coast. So, we had<br />

35 to 40 days to cover the distance, tough but achievable with<br />

the training, experience and mindset of the team.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

A Waiting Game<br />

Unfortunately, our wait for the flight was delayed 3 or 4<br />

times due to the report that the runway at Camp Barneo was<br />

cracking under the unusual movement of the ice. Extensive<br />

cracks appeared in the area which is situated 30 miles from<br />

the North Pole. In previous years there had been signs of<br />

cracks and open water but not to this extent. This was<br />

unprecedented and we had no choice but to sit and wait.<br />

It came to the 8th April and we then needed to speak with<br />

the Canadian team at KBA to discuss our time-limited<br />

expedition which now had been reduced to 20-25 days. KBA<br />

had been monitoring our progress and were becoming<br />

increasingly worried by our delay, especially as they had seen<br />

that for 180 NM off their coast line there was extensive ice<br />

rubble fields - this is extremely difficult to cross. Even<br />

experienced polar teams would have to move slowly through<br />

this area probably covering 6 NM per day. At this point of<br />

the expedition we would hope to be covering over 10 to 15<br />

NM per day.<br />

The more serious issue was that if we encountered any<br />

difficulty in this extensive area it would be almost impossible<br />

14

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

for a plane to land - so their concerns were real. As a team,<br />

we made the tough decision to abort the attempt from the<br />

North Pole to Canada - the reality of climate change was<br />

truly affecting the expedition long before we even had the<br />

chance to set foot on ice.<br />

As mentioned before, this is the point when we learnt that<br />

the Russian government had launched a military exercise<br />

with their Parachute regiment and over 100 soldiers were<br />

based at Camp Barneo. Aside from the Visa issues we had<br />

encountered we speculated that it was this activity that had<br />

delayed our insertion date of the 1st April and the cracked<br />

runway was only part of the story.<br />

Plan D<br />

The Mission statement revisited<br />

Throughout this whole procedure, we were determined not<br />

to be distracted from the original Mission statement, “To film<br />

the harsh honest reality of how global warming has affected<br />

the Arctic Ocean through the eyes of modern day polar<br />

explorers”<br />

We approached VICAAR with a request to be inserted on to<br />

the ocean via helicopter at 88 degrees north to cover the last<br />

two degrees to the North Pole. We received a negative<br />

response from VICAAR who wanted to drop us closer to the<br />

pole as the ice was extremely unstable at 88 degrees. Their<br />

helicopter crew had reported seeing mass open water and<br />

fast-moving ice. We held tough on our request because we<br />

had all of the flotation equipment and training necessary to<br />

deal with this and our main objective was to capture this<br />

unusual activity anyway.<br />

A Green Light was given and at last we finally received the<br />

15

16<br />

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

go ahead from VICAAR that our expedition could<br />

commence. The condition however, was that if we couldn't<br />

reach the North Pole due to problems crossing the ice then<br />

they would pick us up on the 26th April from whatever point<br />

we had reached by then. Even to the last hour we were being<br />

drained of our expedition. We agreed but we didn't go into<br />

the expedition with the same attitude - we were determined<br />

to reach the Pole and document the experience, after all, this<br />

was our entire reason for being there.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Within 24 hours we touched down on the hard-cold ocean<br />

ice having viewed the devastation of the ice from the<br />

helicopter window for over an hour. They dropped our team<br />

onto the arctic ocean and as the helicopter disappeared from<br />

view, we became the most remote team in the world during<br />

the warmest season ever recorded, heading towards the<br />

North Geographic Pole. The expedition on ice had begun<br />

and we all breathed a sigh of relief.<br />

The one memory I have at that point, was the silence, which<br />

was incredibly deafening. I then became aware of the<br />

creaking of the ocean below, followed by the shifting surreal<br />

movement of the ice around us.<br />

There are many individuals or teams around the world who<br />

lay out their plans to run an expedition. Whether it’s<br />

mountains, sea, ice, jungles or deserts, planning and<br />

preparation is the key to the success of the journey.<br />

The amount of blood sweat and tears you need, to even get<br />

the expedition off the ground is almost heart-breaking, for<br />

every positive in the build-up there are 100 negatives. The<br />

desire and belief that you are doing the right thing combined<br />

with the passion to see it through is generally the fuel that<br />

will allow you to finally attempt your journey. But don’t

Plan D<br />

Mark Woods<br />

expect glory or recognition, if you are in this for fame then<br />

you will be disappointed. If you are in it for experiencing<br />

how incredible this planet is and how truly remarkable your<br />

own life can be then its worth every bit of sweat and tears.<br />

Remember if you take up the title of explorer, adventurer or<br />

even professional camper then act accordingly.<br />

With over 30 major expeditions to date, Mark Wood has reached the<br />

Magnetic North Pole, the Geomagnetic North Pole twice, has<br />

completed solo expeditions to both the Geographic North and South<br />

Poles. He has been involved in major BBC and Channel 5<br />

documentaries and over the years has trained and led people to the<br />

extremes of the planet.<br />

Mark aims to communicate globally with schools around the planet,<br />

to have open discussions with students about climate change, cultural<br />

differences, and thinking differently about life.<br />

His own award-winning documentaries have shown the life of dog<br />

teams in Alaska, a solo survival film in the extremes and more<br />

recently a complex cutting edge expedition film showing the harsh<br />

reality of global warming and its effect on the Arctic Ocean as his<br />

team crossed to the North Pole.<br />

Mark is ranked in the top 5 communicators in the world on the<br />

Skype in the Classroom platform and has traveled over 3 million<br />

Skype miles by connecting with children in 34 different countries.<br />

17

Exploring by<br />

the Seat of<br />

Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

Text & Images courtesy of Joe Grabowski<br />

18

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

A decade ago I spent a year bar-tending and traveling in<br />

Australia while my future wife went to teachers’ college in<br />

Wollongong. It was during my adventures Down Under that<br />

I realized I wanted to share my passion for science, nature<br />

and exploration with future generations, and upon returning<br />

to Canada completed teachers’ college. After a couple years, I<br />

realized that I wasn't accomplishing my goal, at least not on<br />

the scale I wanted to.<br />

I began using technology to start opening my classroom to<br />

the world, connecting my students to some scientists during<br />

a biodiversity unit. They had a blast and we quickly set a goal<br />

to connect with 50 scientists, explorers and conservationists.<br />

Joining an expedition on an active volcano in Italy, hanging<br />

out in a penguin colony in Antarctica and chatting with<br />

Fabien Cousteau from the bottom of the ocean barely<br />

scratches the surface of our 52 connections that year. After a<br />

more reasonable 25 connections the following year, it started<br />

to really bother me that only 25 or so students were<br />

benefiting from these experiences.<br />

In the summer of 2015 I launched the non-profit Exploring<br />

by the Seat of Your Pants, with a goal of bringing science,<br />

exploration, adventure, and conservation into classrooms<br />

through virtual guest speakers and field trips. Since<br />

launching, we have run well over 300 Google Hangouts with<br />

tens of thousands of students taking part. Each month we<br />

run 10-20 Google Hangouts, but we also run full day events<br />

celebrating themes like women in STEM, oceans,<br />

biodiversity and space exploration.<br />

This is all 100% free for classrooms, but we do seek out<br />

grants and sponsorships so we can give back to innovative<br />

research, expedition and conservation projects around the<br />

19

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

world.<br />

A classroom favorite is following expeditions around the<br />

world. We'll often connect with adventurers and explorers<br />

before, during and after their return from an expedition. One<br />

of our first was the Amazon River Run, Tarran Kent-Hume<br />

and Olie Hunter Smart were getting ready to kayak the<br />

length of the Amazon. We connected with them in Peru<br />

before departing, in Brazil part way through and back in the<br />

UK upon their successful return. At the moment, we're<br />

following several expeditions including Paul Salopek's<br />

walking of our ancestral migration from Ethiopia to Tierra<br />

20

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

del Fuego, Kate Leeming's preparations to attempt fat biking<br />

across Antarctica and Adam Shoalt's 4,000-mile journey<br />

across the Canadian Arctic.<br />

With the help of a grant, I've been able to fulfill a goal of<br />

bringing classrooms to the most remote regions of the planet.<br />

With several textbook sized BGAN units and satellite time,<br />

we now have the ability to video broadcast from pretty much<br />

anywhere on the planet. The units are sent out with various<br />

explorers and scientists, returned and sent out again. The first<br />

hangouts were from Abaco in the Bahamas with the National<br />

Geographic Blue Holes Expedition, exploring Abaco's blue<br />

21

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants<br />

Joe Grabowski<br />

holes and mapping them in 3D.<br />

We recently broadcast from Clipperton Atoll, the most<br />

remote coral atoll on the planet and currently one of the<br />

units is in Belize, doing weekly broadcasts for classrooms<br />

with archaeologists at an ancient Mayan city. Next school<br />

year we'll start more live streaming, including in 360 Degrees<br />

and on Google Hangouts with classrooms to catch exciting<br />

happenings in the field.<br />

It’s been a wild ride and has led to a journey to the Galapagos<br />

as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow and being named an<br />

Emerging Explorer by National Geographic this year.<br />

Personal accomplishments aside, the goal of Exploring by the<br />

Seat of Your Pants is to help create global citizens by<br />

introducing students to important issues, new places, strong<br />

role models and exciting career paths.<br />

The scientists and explorers who take part in the hangouts<br />

with students often share that they remember a time they saw<br />

a documentary, read an article or met someone that inspired<br />

them and totally changed their path. My hope is that through<br />

these connections, little 'A-ha' moments are happening in<br />

our classrooms.<br />

Joe Grabowski is a Science and Math Teacher and Founder of<br />

Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants.<br />

In 2017 he was acknowledged by National Geographic as an<br />

Emerging Explorer and is a member of the prestigious college of<br />

fellows of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.<br />

@GrabowskiScuba | @ebtsoyp<br />

22

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try<br />

Again. Fail again. Fail better.”<br />

Samuel Beckett<br />

"Westward Ho"<br />

23

How to<br />

Survive in the<br />

Desert<br />

24<br />

John Sullivan<br />

Text & Images © John Sullivan

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

How to Survive in the Desert<br />

John Sullivan<br />

Former Royal Marine Commando, John Sullivan is a<br />

hardened survivor, operating in some of the world’s most<br />

hostile and wildest locals. Owner of Elite Survival Training,<br />

a UK based survival training company, acting as a<br />

motivational speaker, adviser to TV production crews and<br />

survival expert.<br />

If you could have three items when stranded in the desert<br />

what would they be (besides a lot of water)?<br />

Personally, I’d need a personal locator beacon to be maximize<br />

my chances of being found by an emergency search team.<br />

They’ll need to know where I am and they’ll know my exact<br />

location. I’d also like a GPS so I can know where I am and<br />

track my own location in an otherwise featureless<br />

environment. Finally, a satellite phone to call in search teams<br />

and arrange a pick up. Failing that, I’d need a positive<br />

mindset, you can’t predict what’s going to be thrown at you<br />

when exploring so having belief in your own abilities and<br />

knowing how to react to changing circumstances is essential.<br />

How can you orient without a compass when lost in the<br />

desert?<br />

Your best bet is a watch, that’s why I’m always seen wearing<br />

mine. If it’s not noon and you want to find directions during<br />

the day, an analogue watch with minute and hour hands can<br />

be used as a makeshift compass. If possible, make sure the<br />

watch displays the correct time and point the hour hand at<br />

the sun. Whilst holding the watch still imagine an angle<br />

formed by the hour hand and a line from the 12-noon<br />

position to the center of the watch. From there, draw a line<br />

through the middle of the angle. That line will indicate South<br />

in the Northern hemisphere. During daylight savings time,<br />

25

How to Survive in the Desert<br />

John Sullivan<br />

use the one o’clock position over the 12 noon position.<br />

If you’re caught in the Southern hemisphere, point 12 noon<br />

at the sun, instead of the hour hand. Then use your<br />

imagination to create an angle between the hour hand and a<br />

line from the 12 to the center of the watch. The line bisecting<br />

that angle is North.<br />

At night, provided it’s clear, you can use the stars to navigate,<br />

looking for the North Star will allow you to keep your<br />

direction.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

How do you deal with the heat when exposed to the sun?<br />

Your priority should always be to minimize sweat. Keep<br />

your skin covered, even though you probably think wearing<br />

less will keep you cooler. If you must travel anywhere, do it<br />

early in the morning or late in the evening, once the sun has<br />

cooled. From 11am-2pm you should try to rest in the shade,<br />

to avoid the harshest of the sun’s rays.<br />

If I don’t know where I am, should I try to go north,<br />

south, east or west? Should I always stay in the same<br />

direction?<br />

The first thing you’ll want to do is mark in the ground where<br />

you found yourself lost and use that as your starting<br />

position. It’s far better to head back the way you came rather<br />

than pushing forward into the unknown. Believe it or not,<br />

people tend to hope they will find their way back by doing<br />

this. If possible, find some high ground so you can see as<br />

much as possible. Also try looking for signs of life, whether<br />

that be vehicle or animal tracks. Animal tracks will all<br />

inevitably lead you to water, then all you need to do is sit and<br />

wait for a search team as this will assume that’s where you’ll<br />

26

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

head and stand the greatest chance of surviving.<br />

How to Survive in the Desert<br />

John Sullivan<br />

What kind of food should I take on a trip to the desert?<br />

First, you’ll want to factor in how much water you’ll need to<br />

cook your meal. For example, rice and pasta are most likely<br />

no goes, as they’ll need a lot of water to rehydrate and they’ll<br />

make you thirstier. Tinned food such as corned beef and<br />

spam, along with tuna and vegetables is always a safe bet. In<br />

an emergency, you should carry several energy bars – army<br />

ration meals that can be eaten cold and don’t need to be<br />

prepared would be the ideal – such as beef jerky and boiled<br />

sweets.<br />

Is there any way to find some food, and how do I know if<br />

it is edible?<br />

Food will be almost as limited as water. The desert is such a<br />

harsh environment so wildlife and plants will be minimal,<br />

and those you find are more than often hostile. If you are<br />

lucky you might be able to kill a snake, however for obvious<br />

reasons, you may not want to tackle one head on. Looking<br />

for footprints in the morning may lead you back to animals<br />

that are active at night and if you’re lucky – may have the<br />

opportunity to set a trap for the following night.<br />

Where can I find water (and purify it if found)?<br />

Finding water is going to be your greatest challenge in<br />

surviving. Looking for green vegetation is a sure bet that<br />

there’s water nearby, however, it may be deep underground.<br />

Dig down and collect as much as possible. To purify it you<br />

can filter out the dirt using a cloth, such as your shirt or any<br />

cloth you have available. If you can, boil it up and if the<br />

water is really bad, collect the steam in a cloth and wring it<br />

27

How to Survive in the Desert<br />

John Sullivan<br />

out into a separate container. Another way to obtain water is<br />

by building a solar still with plastic sheeting (an opened-up<br />

carrier bag will do) and some form of container.<br />

If I only have five litres of water left, how much water<br />

should I drink per day?<br />

Naturally being in a survival situation can be incredibly<br />

stressful, which will only heighten your thirst. Rationing is<br />

crucial. However, don’t deprive yourself unless completely<br />

necessary, as becoming dehydrated may lead to you<br />

becoming delirious and reduce the positive effects on him.<br />

Personally, I’d try to ration 1.5 liters a day, however I’d also<br />

make sure I was resting in the daytime whilst it’s too hot.<br />

Anything strenuous should be done in the cooler parts of the<br />

day to reduce sweat. Find shade and rest up.<br />

28<br />

John Sullivan at a desert camp in Jordan

29

Haven't You<br />

Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruc<br />

Text & Images © Erden Eruc<br />

30

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

In February 2009 during my human powered<br />

circumnavigation, I landed on the shores of Papua New<br />

Guinea. Upon my return there later, Philip would tell me:<br />

“now even the villagers on the hills know about you, the man<br />

who came from the sea in a yellow boat.” On that February<br />

day, Philip along with other villagers came out from shore in<br />

four dugout canoes, traditional vessels with an outrigger on<br />

one side. A lone truck driver had spotted me at sea earlier<br />

from a dirt road on a hill and had driven ahead to alert them<br />

in the Kamlawa village located a few miles north of Finsch<br />

Harbor.<br />

While bailing water from his own canoe with a tin can, Philip<br />

with a happy attitude said, “we came to rescue you.” I was in<br />

a purpose-built ocean rowing boat in which I had just spent<br />

21 days on the Bismarck Sea and was not in any danger. With<br />

gratitude, I thanked them then they confirmed that a wharf<br />

was available in Finsch Harbor where I could tie my boat. I<br />

rowed my boat to that wharf in the company of their four<br />

canoes. I could hear children from the Kamlawa village<br />

screaming in joy as they ran along the waterfront weaving<br />

among shrubs and coconut trees. A crowd gathered at the<br />

dockside then watched me patiently for three days; taking<br />

their turns to intently observe my every move on the boat.<br />

During the first two days, it was the men who formed a wall<br />

of flesh on the edge of the wharf with their long bush knives,<br />

their universal farming tool, held firmly in their hands. If I<br />

didn't know any better, I could have felt threatened. Later,<br />

the women began to approach and with them came children<br />

of various ages. The earlier stares with intent without saying<br />

a word, were replaced with playtime and the wharf became<br />

their playground; I was amused to watch their daring diving<br />

stunts.<br />

31

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

It is a curious experience to have become part of a local<br />

legend in a faraway land. I wonder how the story will differ<br />

after a few generations and what the children will hear from<br />

their elders about my journey which touched their<br />

community. I also visited a primary school while in<br />

Kamlawa; I don't know if any of my own stories were ever<br />

incorporated into the local version.<br />

When asked to explain what I was doing, I told them that I<br />

was on a walkabout and that I was a storyteller, that I visited<br />

different places on my journey and gathered stories. My job<br />

was to become the best storyteller. I explained that I was<br />

going to tell about the kindness that I received in Kamlawa<br />

for example, and the world was going to know.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

In March 2003 while the Alaska Highway was still snow<br />

packed, I rode my bicycle through Fort Nelson in British<br />

Columbia in Canada toward Alaska. Earlier while at Fort St.<br />

John also in British Columbia further south, a First Nations<br />

man had brought his two children to meet me for breakfast,<br />

asking me to “tell them about my vision.” They perceived my<br />

journey as a vision quest, a journey toward wisdom. They<br />

then had alerted the Fort Nelson First Nation of my arrival<br />

unbeknownst to me. I was greeted on the highway at Fort<br />

Nelson before being invited to visit the Chalo Elementary<br />

School in their village.<br />

Though a common occurrence during the tourist season, I<br />

was the only bicyclist on the icy roads at that time. I was on a<br />

bicycle with studded tires, carrying front and rear panniers<br />

and towing a trailer loaded with my climbing gear for a climb<br />

of Mt. McKinley in Alaska. Wearing heavy clothing to stay<br />

warm, keeping a water bladder next to my back to keep it<br />

from freezing, I was a spectacle on the move. I have learned<br />

that everyone sees what I do through their own mind's eye,<br />

32

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

and that their respective life experiences determine what they<br />

see in what I do. Children were no different.<br />

“Aren't you afraid?” They asked me, and when I enquired<br />

what I should fear, they would tell me about their own fears.<br />

“Aren't you afraid of the bears?”<br />

“It is winter, they are asleep.”<br />

“Aren't you afraid of the trucks?”<br />

“They change lanes.”<br />

“Aren't you afraid of loneliness?”<br />

“I’ve got you” and so on.<br />

I urged them to think that fear should not stop us from what<br />

we envision to do. We usually fear what we don't know, but<br />

by seeking knowledge we can learn how to handle fear.<br />

Without realizing, the children were telling me about their<br />

own fears and all the reasons for why they would not<br />

attempt what I was doing. I demonstrated and told them that<br />

with proper preparation and hard work, it is possible to<br />

accomplish our dreams. I would later realize that if I slightly<br />

detached myself from the encounter, I could have taken on<br />

the role of a virtual mirror. Questions asked about my<br />

journey would provide hints about the individuals asking<br />

them.<br />

I always found the fourth through eighth grade students to<br />

be the best age group to address. I could hold their attention<br />

through a structured presentation. For them anything was<br />

possible, children of this age group were open minded and<br />

33

34

Rowing across the Pacific Ocean<br />

in December 2007, day 168.<br />

35

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

they appreciated that the world was a big place, exciting<br />

adventure stories captivated them. With younger children, I<br />

learned that the best contribution I could make was to spend<br />

quality time together, talking about bugs and bears and<br />

sharing pictures of the creatures of this world. I would play<br />

along, allow them to set the pace and dwell on any image that<br />

entertained and intrigued them. The important thing was that<br />

each student had an example or an idea about how a lifetime<br />

of involvement with sports could help someone.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

In all my primary school level gatherings, I have been serving<br />

to create a series of learning moments to grab their full<br />

attention, which could be used to deliver important messages<br />

to remember. My messages are woven into my stories like the<br />

fables of La Fontaine; I touch on my own mistakes which<br />

they should avoid, I regularly engage them in topics<br />

including wellness and caring for the environment.<br />

I am fifty years old now, and I like having children guess my<br />

age. I ask children about what one needs to do to maintain a<br />

level of fitness for what I do. They usually offer ideas from<br />

good food to sufficient sleep to regular exercise. My goal is to<br />

leave them with a non-smoking message. If they don't smoke<br />

they can play catch with their grandchildren, I tell them,<br />

knowing full well that most grandparents are no longer<br />

physically active. These children crave such attention and my<br />

message resonates with them so they will not forget.<br />

Power of Dreams<br />

Dreams are the fertile ground where the future is shaped.<br />

Beware what you think for you may decide to act on it, I had<br />

read somewhere. From a young age, I have been involved in<br />

various sports and physical activities. At the age of 5, my<br />

father took me up Mt. Erciyes, an almost 4000-meter extinct<br />

36

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

volcano in south central Turkey. When I was in middle<br />

school, our teachers brought a black and white television to<br />

the classroom then told us to pay attention. We watched<br />

astronauts walk on the moon that day. I had read Jules Verne<br />

books, been watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries, and I<br />

was ready for the obvious leap of imagination. I can be an<br />

astronaut, I thought to myself. Given time though, I<br />

reasoned in my child's mind that all astronauts were<br />

American but I was not, therefore I could not be, unaware of<br />

cosmonauts at the time, and never pursued the thought from<br />

then on. No teacher was aware of my internal processing;<br />

they had not done any follow up exercises after the events.<br />

My parents could not have known; I was a boarding student.<br />

When I was at the age of 15, I was in Belgium where I came<br />

across an issue of the National Geographic magazine<br />

dedicated to the 1963 first American ascent of Everest. I had<br />

to look up the word bivouac in the dictionary to understand<br />

the articles; I can climb Everest, I told myself. Perhaps<br />

because I was older by then, that idea has never left me since.<br />

In 1997 at age 36, I found myself standing often in front of a<br />

world map hanging on the wall of our software development<br />

lab in Washington, DC in United States. I was pursuing a<br />

successful consultancy career, yet when I shifted my gaze out<br />

the window, I pictured myself on the final steps of a difficult<br />

snowbound summit, or on a steep big wall climb. My dreams<br />

never had any corner offices or worldly possessions.<br />

Visualization had been happening, wiring my brain in<br />

different ways than required for a life in the office.<br />

That world map had the Americas on the right, the Pacific<br />

Ocean in the middle and the Old World on the left. I traced<br />

my finger over that map one day right to left from<br />

Washington, DC to Turkey, and even gave it a name:<br />

37

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

Top: March 16, 2013 - With officers and the other awardees James Cameron and Chris Nicola<br />

during the Explorers Club Annual Dinner where I was awarded a Citation of Merit.<br />

Above: July 2011, making progress in Zambia.<br />

38

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

Top: May 2012 - On my approach to Louisiana on the Gulf of Mexico, birds migrating north<br />

from the Yucatan Peninsula to continental USA found respite on my boat. This is an Eastern<br />

Wood Pewee that I practically had to hug to capture this image.<br />

Above: May 2010 - A road sign unique to Australia on the Nullarbor Plain: watch out for feral<br />

camels, wombats and kangaroos.<br />

39

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

“Journey Home.” What if, I asked, what if I could do it by<br />

human power? That became a quiet obsession followed by<br />

numerous how-questions. How would I find the time, how<br />

would I obtain the funding? Each how-question was a<br />

problem to be solved. It was easy tracing paths on a map;<br />

maybe I would not stop in Turkey and I would keep going<br />

until I returned to DC. I would have to contend with<br />

crossing the Atlantic Ocean on my way, which is when I<br />

discovered the Ocean Rowing Society in London. As an<br />

engineer, I was already wired as a problem solver, now I was<br />

on familiar turf.<br />

Peer pressure<br />

There is only one thing that is certain in life which holds true<br />

for all ages: if we believe that we cannot be, then our<br />

subsequent actions ensure that outcome. However, if we<br />

begin with the belief that we can, our whole intention<br />

changes, we recompose to apply our time and resources<br />

toward that positive goal, focusing our energies to make it<br />

happen. Our place in the world is the result of consecutive<br />

decisions that we have made at critical junctions in our lives;<br />

those decisions were necessarily aligned with our goals and<br />

the probability of success that we assigned the same.<br />

Children don't know that yet, and I want them to catch each<br />

other whenever they utter the words “I can't” - an expression<br />

which comes so naturally to them.<br />

Call me devious, I trick the students after I share my<br />

astronaut story, by asking them who wants to be an<br />

astronaut. Many times, it is something none of them had even<br />

considered. One or two hands go up often with hesitation<br />

but invariably few others laugh at these future cadets. That<br />

scenario never fails, always providing me with the<br />

opportunity to talk about negative peer pressure.<br />

40

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

In adults, this takes on a different form where cynicism is<br />

billed as critical thinking. When I shared my thoughts with<br />

others about Journey Home early on, I quickly found that<br />

not everyone needed to know. Have you done anything like<br />

that before, was a typical response. Books never turned me<br />

down; one of the books that I read was titled “Ultimate<br />

High” about the Swede Göran Kropp, who had bicycled<br />

from Sweden to Nepal towing his climbing gear on a trailer,<br />

and had climbed Everest solo in 1996.<br />

When I finally met Göran in person in Seattle during the<br />

summer of 2001, his first two questions to me were: when are<br />

you starting, and, do you have sponsors. I then hesitated<br />

about whether to begin my journey because the 9/11 events<br />

which provided yet another excuse to wait. When I later met<br />

Göran in Ouray Ice Park in Colorado in the winter of 2002,<br />

he would ask me “haven't you started yet?” – I remember<br />

feeling uncomfortable giving my excuses. That is an example<br />

to positive peer pressure.<br />

When I declared in 2003 that I was going to bicycle from<br />

Seattle to Alaska in winter conditions to climb Mt. McKinley,<br />

I knew to ignore the cynicism. If I bicycled 50 miles a day, I<br />

knew I could reach Alaska by mid-April before my team<br />

arrived for our scheduled climb in May. Those who had<br />

asked whether I had bicycled that far before, did not bother<br />

showing up at the starting line on February 1st. I would<br />

reach Anchorage on April 11th.<br />

Children need to hear such stories often to learn to identify<br />

around them the few nurturing individuals who will affirm<br />

their aspirations and to avoid those who will damage their<br />

self-esteem. Our legal counsel Christopher Beer had told me<br />

when we were filing to establish Around-n-Over as a nonprofit:<br />

“surround yourself with good people and the dream<br />

41

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

will take care of itself” -- likewise we often tell children to<br />

choose their friends well, for good reason.<br />

Willingness to commit<br />

Dreams do not become reality without deliberate action. I<br />

remember myself uttering “a dream without action is only a<br />

pipe dream,” during a presentation to students at the Hutch<br />

School in Seattle for children of families with cancer.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Everything has a price, there is no free lunch. It is easy to<br />

remain in our comfort zone to avoid the tough choices in fear<br />

of failure. I used to think that when I found sponsors I could<br />

begin my journey. I had a career to advance and a job which<br />

paid the bills. Mortgage on a condo with a lake view near<br />

downtown Seattle required a steady income. I was a creature<br />

of habits, wanting certainty before action.<br />

In September 2002, I received an email from Göran telling<br />

me that he was back at his home in Issaquah east of Seattle<br />

after another successful ascent of Everest. We quickly<br />

decided to go rock climbing for the first time together in<br />

eastern Washington State. Tragically, Göran fell that day on a<br />

relatively short pitch and died while on my belay. That event<br />

shook me deep within, forced a reconsideration of my<br />

priorities. I was not one to hide in a corner feeling sorry for<br />

myself. What came out of that accident was a firm belief that<br />

I was the chosen one, that there was a reason for why I was<br />

there, and that life was short.<br />

During the flight on the way back from Göran's funeral in<br />

November that year, I drew the world map on a piece of<br />

paper and marked the highest summit on each continent<br />

except Mt. Vinson in Antarctica. I would carry out my<br />

circumnavigation, and I would also reach each of these six<br />

42

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

summits by human power in honor of Göran's memory.<br />

First to reach was the highest summit in North America,<br />

namely Mt. McKinley in Alaska.<br />

When I contacted Göran's sponsors, I received a loud silence.<br />

Before the accident, that would have been a valid excuse to<br />

postpone the journey. The time for excuses was over; no<br />

longer were they going to dictate my destiny. With the<br />

blessing of Nancy, my then fiancée, I cashed out my<br />

retirement funds and began pedaling north. Before my<br />

departure, the legal paperwork for Around-n-Over was filed,<br />

my living will and powers of attorney left in Nancy's care.<br />

Our team summited McKinley on 29 May, and Nancy<br />

married me in Alaska following my descent.<br />

This was only the beginning. After my return, we sold our<br />

second car and the condo in favor of lesser expenses. We<br />

rented first, then bought a townhouse at half the mortgage<br />

obligation. We acted to roll equity from another property<br />

that I had owned in Washington, DC into a profitable rental<br />

unit. We took advantage of lower mortgage rates to reduce<br />

our monthly expenses.<br />

By the time I launched on the Pacific Ocean in 2007 to begin<br />

my westbound circumnavigation, I had bought a rowboat<br />

and had used it once already for a solo practice row on the<br />

Atlantic Ocean from the Canary Islands near north-western<br />

Africa to the Caribbean Sea. Nancy and I had rearranged our<br />

lives to survive on one salary, totally committing ourselves to<br />

the journey. I had even gained Aktaş Holding from Turkey as<br />

a major sponsor. The departure became possible after the<br />

tough choices we had made together with Nancy.<br />

That day at the Hutch School, I was in front of children a<br />

43

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

family member of whom was under treatment for cancer. I<br />

told them that death will happen around us in our lifetime.<br />

Rather than death itself, we could focus on what to do with<br />

that experience. After Göran's death, I had changed my own<br />

path drastically, yet they were still so young. Could they start<br />

by telling how they loved the ailing one, or promise the same<br />

one that they will be strong, caring, honorable, honest, and<br />

hardworking individuals with integrity?<br />

The question perhaps all of us should ask ourselves is<br />

whether we should wait for a disruptive event like death, or<br />

layoff, or divorce, or childbirth to shake our foundation<br />

before we take the proverbial first step on a journey of a<br />

thousand miles.<br />

44<br />

November 2009 - a magnificent beetle that I found during the north to south traverse of Papua<br />

New Guinea using the Kokoda Track.

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Creating value for the society<br />

When preparing for my journey in the aftermath of Göran's<br />

accident, I felt the need to incorporate the venture. I was<br />

introduced to our legal counsel Christopher Beer with whom<br />

to consider our options. A non-profit corporation with a<br />

mission to educate and inspire children was the outcome. I<br />

did not want my journey to turn into a chest beating exercise<br />

and I was passionate about creating opportunities toward<br />

children's education.<br />

Once we had a stable board of directors, our charitable work<br />

became better defined. We seized opportunities to partner<br />

with another non-profit called İLKYAR to help boarding<br />

school students at primary school age in rural Turkey, and<br />

with African Environments in Arusha on the foothills of Mt.<br />

Kilimanjaro to build additional classrooms at a local<br />

secondary school.<br />

As athletes, we often receive generous support from the<br />

society; recognition is just one of the rewards that come with<br />

success. We have a choice to handle that success responsibly<br />

and to pay back the society for the privilege. When that any<br />

worthy endeavor can be leveraged to benefit the society<br />

becomes our intention, we will find the ways. I was never<br />

invited to schools when I was working as an engineer. Now<br />

that I am, influencing the next generation through my stories<br />

is just one of the ways.<br />

Motivation through goal setting<br />

What if I cannot finish my circumnavigation, was one of my<br />

questions early on. It was such a huge undertaking, daunting<br />

in scope and overwhelming in duration. In front of me was a<br />

45

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

typical fishbone diagram which fed input from four distinct<br />

boxes into one which represented results and success. The<br />

four boxes to populate had men, money, materials and<br />

methods as their respective titles. But to what end? The final<br />

box contained the key... If I engaged as many children as<br />

possible to broaden their horizons, ran an accountable nonprofit<br />

true to its mission, created as much value as possible<br />

for my sponsors, and made as many friends as possible<br />

around the world during my journey, then I would be in<br />

keeping with my intentions.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

When I focused on our performance along the way rather<br />

than on the outcome at the end, the fog lifted, I gained clarity<br />

of purpose. I could take this seemingly impossible goal,<br />

which was literally as big as the world then divide it into<br />

tangible relevant bite-size intermediate goals. Perhaps our<br />

team members could take on some of these tasks, and with<br />

their individual skills could deliver better results. I certainly<br />

did not have the time to juggle all the responsibilities. My job<br />

was to improve the significance of our non-profit programs,<br />

to better myself through the wisdom gained during my<br />

journey, and to enhance the quality of my observations for<br />

better storytelling. If world events got in the way, or an ailing<br />

family member became a priority in my life, I could look<br />

back and say: “we've done well!”<br />

The US Marines have coined the expression, “difficult we can<br />

do now; impossible will take longer.” What they left out of<br />

“difficult” was whether it was realistic. Every step along the<br />

way toward that long-term goal has to consist of achievable<br />

short-term goals. If dreams give us ideas, it is the goals which<br />

provide us with the roadmap. If these goals are very specific<br />

and performance can be measured upon their completion, we<br />

can then press ourselves for meeting timelines. If we are<br />

falling short on resources such as time, money or talent, we<br />

46

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

can consider prioritizing the tasks. Unless there are<br />

dependencies among the tasks where one cannot begin the<br />

next step until completion of the previous, then prioritizing<br />

will relieve the pressure for performance. At any given<br />

moment, the top three focus areas can be retired once<br />

addressed and a new selection can replace them. It is the<br />

pursuit of excellence, not perfection which makes the<br />

difference. And none of this is possible unless we can take a<br />

moment to think ahead and make a plan.<br />

I was able to overcome the inertia created by an unwieldy<br />

dream by breaking it down into stages. Then by seeing<br />

progress because of my efforts, I was able to remain<br />

motivated and to maintain my momentum.<br />

Dream big<br />

If we know how to handle big dreams by defining a longterm<br />

goal and breaking it down to its intermediate<br />

milestones, then we should not fear big dreams. In other<br />

terms, an insignificant dream will mean under achievement of<br />

our potential.<br />

Taking part in the Olympics is every athlete's dream, and<br />

why not? As long as the athlete and the coaches and the<br />

administrators surrounding the athlete are all aware of the<br />

seriousness of the undertaking, it can be a valid dream.<br />

Measuring our performance against others who are best in<br />

their field will magically force us to set higher standards for<br />

ourselves. Other than nature versus nurture debates which<br />

could be had at this point, limited time also must be<br />

considered.<br />

If we accept that we have a limited time to achieve our<br />

dreams, then big dreams will mean many small steps or fewer<br />

47

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

Top: Oct 2010 - Rowing on the Indian Ocean northwest of Madagascar.<br />

Above: Sept 2009 - Beach walking along the Solomon Sea shores in Papua New Guinea.<br />

48

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

Top: Students feeling my biceps to see how strong I am.<br />

Above: Oct 2009 - sea kayaking along the Solomon Sea shores of Papua New Guinea.<br />

49

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

more significant steps to achieve. My human powered<br />

circumnavigation can be a good example.<br />

This circumnavigation will be finished when I return to<br />

California hopefully in the summer of 2012, after a five-year<br />

struggle. Yet just in the process of bringing my journey this<br />

far, I have become the first person to have rowed three<br />

oceans and the first person to have rowed the Indian Ocean<br />

mainland to mainland between Australia and Africa. I hold<br />

the Guinness World Record for the longest time at sea by a<br />

solo rower by 312 days, and I remain the most experienced<br />

ocean rower alive in total career days at sea by 655 days as of<br />

October 10, 2011.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

I am writing this article on a small PDA while rowing across<br />

the South Atlantic from Lüderitz in Namibia to Central<br />

America. By the time I am done, my total career days will<br />

probably exceed 800. I did not set out to gather all these<br />

specific records, yet I was reaching for such a big goal in my<br />

circumnavigation that they had to happen along the way.<br />

Manage the dream<br />

The beauty of intermediate goals is that they provide<br />

milestones toward success. Each milestone achieved is a taste<br />

of success. Repeated often, success becomes a habit, it<br />

becomes an acquired skill, it is not accidental. We build on<br />

past successes as well as failures to learn from our mistakes.<br />

Wearing a typical project manager's hat, I divide my journey<br />

into stages, and those into phases. Each stage requires<br />

planning, then preparation, then execution then an evaluation<br />

phase. US Rangers have their 6P's: “prior planning prevents<br />

piss poor performance.” Based on my plans, I then have to<br />

prepare myself. Preparations may include physical fitness,<br />

50

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Haven't You Started Yet?<br />

Erden Eruç<br />

gaining the additional skills as necessary, gathering the<br />

equipment and supplies, prepositioning them for logistical<br />

ease, getting visas or permits and finding funding. When I<br />

execute the plan, I use the fruits of these preparations to<br />

move my journey forward. Evaluation is a time when I<br />

reflect on the phase I just completed, learn from my mistakes,<br />

and identify weaknesses or areas to improve, then<br />

acknowledge and reinforce the good parts. The cycle is<br />

complete when I am ready to incorporate these in the<br />

planning phase of the next stage.<br />

To move my journey across PNG (Papua New Guinea) for<br />

example, I had to plan and prepare for beach walking, sea<br />

kayaking, hiking through tropical mountain paths then<br />

rowing. Before departure for PNG, I had to arrange for the<br />