DT e-Paper, Saturday, October 15, 2016

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

14<br />

SATURDAY, OCTOBER <strong>15</strong>, <strong>2016</strong><br />

<strong>DT</strong><br />

Climate Change<br />

The river that eats up land and homes<br />

• Rafiqul Islam<br />

Piyara Begum once had a<br />

happy life in Garuhara<br />

village by the Brahmaputra<br />

River in northern<br />

Bangladesh, but worsening erosion<br />

of the river banks has displaced<br />

her family seven times.<br />

Now Piyara, 30, has taken<br />

shelter in Panchgachi village, 8<br />

kilometres away in the same subdistrict<br />

of Kurigram Sadar.<br />

“I am always concerned about<br />

where Piyara and her three<br />

children are living, and how she<br />

manages her family expenses,<br />

as she has lost everything due to<br />

erosion,” said her uncle, Abdul<br />

Majid, who still lives in Garuhara<br />

village.<br />

The loss of Piyara’s home is<br />

taking a toll on her mental and<br />

physical health, he added.<br />

Riverbank erosion is a common<br />

problem along the mighty<br />

Brahmaputra during the monsoon,<br />

but scientists say climate change<br />

is making the phenomenon worse<br />

by contributing to higher levels of<br />

flooding and siltation.<br />

According to villagers in<br />

Garuhara, about 200 families have<br />

been displaced by erosion there in<br />

the last two years.<br />

Majid fears that if the trend<br />

continues, the whole of the village<br />

will go underwater, rendering<br />

about 1,000 families homeless.<br />

But some of those who want<br />

to escape that prospect cannot -<br />

because they are unable to turn<br />

their assets into the cash they<br />

need to pay for their move.<br />

Abdul Malek, 45, a farmer<br />

in Garuhara, had 0.4 acres of<br />

agricultural land on the bank of<br />

the Brahmaputra, but the river<br />

washed away half his plot during<br />

the monsoon last year.<br />

“My family had no problem in<br />

the past as we cultivated crops on<br />

the land to meet our food demand.<br />

But now we are facing trouble,”<br />

he said.<br />

Malek and his family are<br />

planning to migrate to another<br />

part of the country after selling<br />

their homestead, but they cannot<br />

find a buyer because the property<br />

is at high risk of erosion.<br />

Other families in Garuhara<br />

village who also want to sell up<br />

and leave are trapped there for the<br />

same reason.<br />

Erosion rates rising<br />

The Brahmaputra is a<br />

transboundary river, originating<br />

in southwestern Tibet, flowing<br />

through the Himalayas, India’s<br />

Assam State and Bangladesh, and<br />

out into the Bay of Bengal.<br />

Climate change has contributed<br />

to rapid siltation of the river in<br />

recent years, which is intensifying<br />

bank erosion during the monsoon,<br />

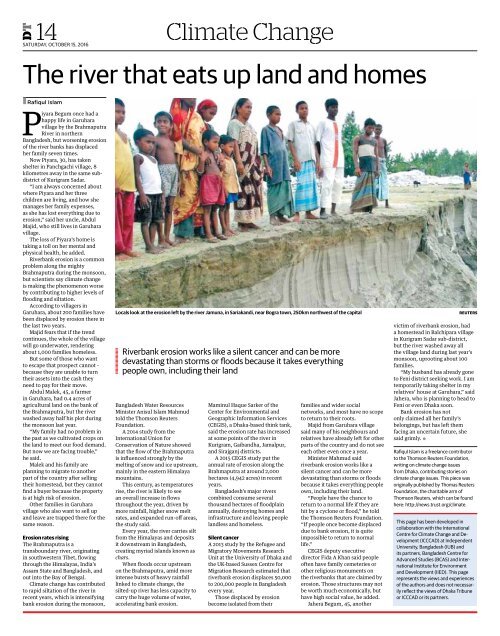

Locals look at the erosion left by the river Jamuna, in Sariakandi, near Bogra town, 250km northwest of the capital<br />

Riverbank erosion works like a silent cancer and can be more<br />

devastating than storms or floods because it takes everything<br />

people own, including their land<br />

Bangladesh Water Resources<br />

Minister Anisul Islam Mahmud<br />

told the Thomson Reuters<br />

Foundation.<br />

A 2014 study from the<br />

International Union for<br />

Conservation of Nature showed<br />

that the flow of the Brahmaputra<br />

is influenced strongly by the<br />

melting of snow and ice upstream,<br />

mainly in the eastern Himalaya<br />

mountains.<br />

This century, as temperatures<br />

rise, the river is likely to see<br />

an overall increase in flows<br />

throughout the year, driven by<br />

more rainfall, higher snow melt<br />

rates, and expanded run-off areas,<br />

the study said.<br />

Every year, the river carries silt<br />

from the Himalayas and deposits<br />

it downstream in Bangladesh,<br />

creating myriad islands known as<br />

chars.<br />

When floods occur upstream<br />

on the Brahmaputra, amid more<br />

intense bursts of heavy rainfall<br />

linked to climate change, the<br />

silted-up river has less capacity to<br />

carry the huge volume of water,<br />

accelerating bank erosion.<br />

Maminul Haque Sarker of the<br />

Center for Environmental and<br />

Geographic Information Services<br />

(CEGIS), a Dhaka-based think tank,<br />

said the erosion rate has increased<br />

at some points of the river in<br />

Kurigram, Gaibandha, Jamalpur,<br />

and Sirajganj districts.<br />

A 20<strong>15</strong> CEGIS study put the<br />

annual rate of erosion along the<br />

Brahmaputra at around 2,000<br />

hectares (4,942 acres) in recent<br />

years.<br />

Bangladesh’s major rivers<br />

combined consume several<br />

thousand hectares of floodplain<br />

annually, destroying homes and<br />

infrastructure and leaving people<br />

landless and homeless.<br />

Silent cancer<br />

A 2013 study by the Refugee and<br />

Migratory Movements Research<br />

Unit at the University of Dhaka and<br />

the UK-based Sussex Centre for<br />

Migration Research estimated that<br />

riverbank erosion displaces 50,000<br />

to 200,000 people in Bangladesh<br />

every year.<br />

Those displaced by erosion<br />

become isolated from their<br />

families and wider social<br />

networks, and most have no scope<br />

to return to their roots.<br />

Majid from Garuhara village<br />

said many of his neighbours and<br />

relatives have already left for other<br />

parts of the country and do not see<br />

each other even once a year.<br />

Minister Mahmud said<br />

riverbank erosion works like a<br />

silent cancer and can be more<br />

devastating than storms or floods<br />

because it takes everything people<br />

own, including their land.<br />

“People have the chance to<br />

return to a normal life if they are<br />

hit by a cyclone or flood,” he told<br />

the Thomson Reuters Foundation.<br />

“If people once become displaced<br />

due to bank erosion, it is quite<br />

impossible to return to normal<br />

life.”<br />

CEGIS deputy executive<br />

director Fida A Khan said people<br />

often have family cemeteries or<br />

other religious monuments on<br />

the riverbanks that are claimed by<br />

erosion. Those structures may not<br />

be worth much economically, but<br />

have high social value, he added.<br />

Jahera Begum, 45, another<br />

REUTERS<br />

victim of riverbank erosion, had<br />

a homestead in Balchipara village<br />

in Kurigram Sadar sub-district,<br />

but the river washed away all<br />

the village land during last year’s<br />

monsoon, uprooting about 100<br />

families.<br />

“My husband has already gone<br />

to Feni district seeking work. I am<br />

temporarily taking shelter in my<br />

relatives’ house at Garuhara,” said<br />

Jahera, who is planning to head to<br />

Feni or even Dhaka soon.<br />

Bank erosion has not<br />

only claimed all her family’s<br />

belongings, but has left them<br />

facing an uncertain future, she<br />

said grimly. •<br />

Rafiqul Islam is a freelance contributor<br />

to the Thomson Reuters Foundation,<br />

writing on climate change issues<br />

from Dhaka, contributing stories on<br />

climate change issues. This piece was<br />

originally published by Thomas Reuters<br />

Foundation, the charitable arm of<br />

Thomson Reuters, which can be found<br />

here: http://news.trust.org/climate.<br />

This page has been developed in<br />

collaboration with the International<br />

Centre for Climate Change and Development<br />

(ICCCAD) at Independent<br />

University, Bangladesh (IUB) and<br />

its partners, Bangladesh Centre for<br />

Advanced Studies (BCAS) and International<br />

Institute for Environment<br />

and Development (IIED). This page<br />

represents the views and experiences<br />

of the authors and does not necessarily<br />

reflect the views of Dhaka Tribune<br />

or ICCCAD or its partners.