Army - Kicking Tires On Jltv

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

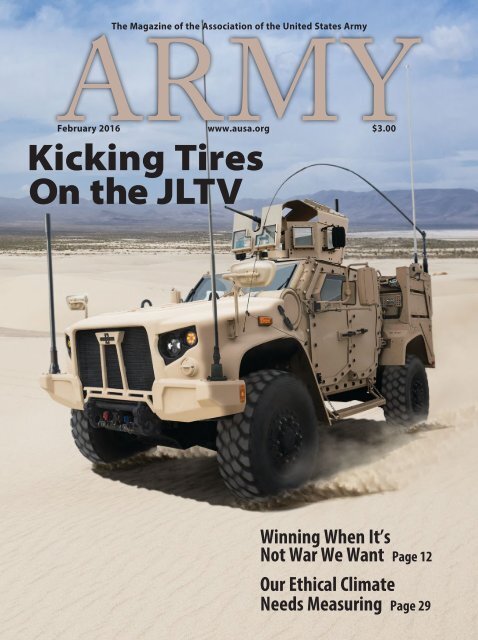

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

ARMY<br />

February 2016 www.ausa.org $3.00<br />

<strong>Kicking</strong> <strong>Tires</strong><br />

<strong>On</strong> the JLTV<br />

Winning When It’s<br />

Not War We Want Page 12<br />

Our Ethical Climate<br />

Needs Measuring Page 29

ARMY<br />

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

February 2016 www.ausa.org Vol. 66, No. 2<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

LETTERS....................................................3<br />

SEVEN QUESTIONS ..................................5<br />

WASHINGTON REPORT ...........................6<br />

NEWS CALL..............................................7<br />

FRONT & CENTER<br />

Readiness and Capability<br />

Are Intertwined<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.<br />

Page 11<br />

Winning the War We’ve Got,<br />

Not the <strong>On</strong>e We Want<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.<br />

Page 12<br />

Yep, Those Were the Good Old<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Days<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, USA Ret.<br />

Page 14<br />

FEATURES<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Women: Highlights<br />

With the announcement lifting gender<br />

restrictions on all military jobs, we take a<br />

pictorial look at the role of female soldiers<br />

throughout U.S. history. Page 18<br />

Cyber Capabilities Key to<br />

Future Dominance<br />

By Lt. Gen. Edward C. Cardon<br />

Unlike the other domains, cyberspace is<br />

continuously evolving and adapting along<br />

with each entrepreneur, inventor and actor<br />

using it. To retain dominance, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

must keep up with this evolution. Page 22<br />

Muscle for an Uncertain World:<br />

Performance, Payload and<br />

Comfy Seats<br />

Stories by Scott R. Gourley<br />

The latest generation of Joint Light<br />

Tactical Vehicles has moved well<br />

beyond the traditional role of <strong>Army</strong><br />

trucks and into the realm of what can<br />

be described as “muscle trucks.”<br />

Page 36<br />

Cover Photo: The independent suspension<br />

system in the Joint Light Tactical<br />

Vehicle allows it to traverse the toughest<br />

terrains.<br />

Oshkosh Corp.<br />

18<br />

14<br />

HE’S THE ARMY......................................17<br />

THE OUTPOST........................................57<br />

SUSTAINING MEMBER PROFILE...........60<br />

SOLDIER ARMED....................................61<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING.....................63<br />

REVIEWS.................................................65<br />

FINAL SHOT ...........................................72<br />

22<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 1

Fighting for Relevancy in the Gray Zone By Maj. David B. Rowland<br />

Successfully responding to conflicts that exist between normal international<br />

competition and open conflict requires the <strong>Army</strong>’s conventional forces to alter<br />

training mentality and methodology. Page 26<br />

Curtain’s Always Rising<br />

For Theater <strong>Army</strong><br />

By Lt. Gen. James L. Terry, USA Ret.<br />

Recent events provide a vehicle for<br />

exploring the versatility of the theater<br />

<strong>Army</strong> in a manner far more dynamic than<br />

its equally important role as an <strong>Army</strong><br />

service component command. Page 49<br />

49<br />

It’s Time to Establish<br />

Ethics-Related Metrics<br />

By Col. Charles D. Allen, USA Ret.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> needs to construct a way to<br />

measure the character of its leaders and<br />

ethics within the profession of arms to<br />

ensure we are “getting it right.” Page 29<br />

Creativity Could Boost<br />

Regionally Aligned Forces Concept<br />

By Col. Allen J. Pepper<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leadership’s vision involves a force<br />

that is globally responsive and regionally<br />

engaged. An important aspect of turning<br />

this vision into reality is the concept of<br />

regionally aligned forces. Page 32<br />

40<br />

Creative Answers for Sagging Morale<br />

By Capt. Robert C. Sprague<br />

<strong>On</strong>e of the most critical ideas to foster<br />

within an organization is innovation;<br />

without it, soldiers are doomed to repeat<br />

the same errors indefinitely. Page 43<br />

The Evolving Art of Training<br />

Management<br />

By Col. David M. Hodne and Maj. Joe Byerly<br />

An evolution in training management is<br />

reflected in current <strong>Army</strong> doctrine and is<br />

fueled by the hard-earned combat<br />

experience of leaders across the <strong>Army</strong>, new<br />

digital training tools, and an institutional<br />

resurgence in Mission Command. Page 45<br />

Birth Era May Factor in Risk<br />

of Suicide<br />

By Col. James Griffith, ARNG Ret.,<br />

and Craig Bryan<br />

The marked increase in soldier suicides may<br />

not be related to deployment, combat<br />

participation or an overall high operating<br />

tempo but instead, an indication of a<br />

broader trend of increased vulnerability<br />

among more recent generations of young<br />

adults. Page 53<br />

53<br />

Deep Roots of the <strong>Army</strong>’s<br />

Dental Corps<br />

By Daniel J. Demers<br />

From its inception in 1901 after Spanish-<br />

American War veterans experienced<br />

extraordinary dental problems, the U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Dental Corps has grown in size, skill<br />

and influence. Page 40<br />

45<br />

2 ARMY ■ February 2016

Letters<br />

Good Mentoring Makes<br />

Good Memories<br />

■ I was delighted to see the article by<br />

retired Maj. Wayne Heard in the December<br />

issue, “Mentoring Stands Test of<br />

Time,” about Col. Robert L. Jackson.<br />

Jackson was a great man, and I owe much<br />

to him. I worked for him when he was<br />

the deputy chief of staff for operations of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Pacific. His counsel, coaching<br />

and friendship helped me through some<br />

very challenging times. Kudos to Heard.<br />

Col. Lawrence E. Casper, USA Ret.<br />

Oro Valley, Ariz.<br />

AUSA FAX NUMBERS<br />

ARMY magazine welcomes letters to<br />

the editor. Short letters are more<br />

likely to be published, and all letters<br />

may be edited for reasons of style,<br />

accuracy or space limitations. Letters<br />

should be exclusive to ARMY magazine.<br />

All letters must include the<br />

writer’s full name, address and daytime<br />

telephone num ber. The volume<br />

of letters we receive makes individual<br />

acknowledgment impossible. Please<br />

send letters to The Editor, ARMY magazine,<br />

AUSA, 2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington,<br />

VA 22201. Letters may also<br />

be faxed to 703- 841-3505 or sent via<br />

email to armymag@ausa.org.<br />

Share Battle of Ganjgal Lessons<br />

■ Another excellent essay by retired<br />

Col. Richard D. Hooker Jr. (“‘Ride to<br />

the Sound of the Guns,’” September).<br />

How does ARMY magazine keep finding<br />

great writers, decade after decade?<br />

But I request a follow-up article on<br />

why so many leaders did not provide<br />

support to the warriors in battle that<br />

day. Why was it necessary for “the <strong>Army</strong><br />

[to act] swiftly to fix responsibility after<br />

the battle, issuing career-ending reprimands<br />

to key leaders judged to have been<br />

at fault”?<br />

We read, for example: “Meanwhile,<br />

the battalion commander [of a unit that<br />

had been radioed for fire support] remained<br />

in his office.” But it seems implausible<br />

for one who has risen to that<br />

position and rank to intentionally repudiate<br />

responsibility.<br />

Had he just returned from an exhausting<br />

patrol and fallen asleep at his desk?<br />

Was he talking to his family back home?<br />

Had he even been made aware of the situation<br />

on the ground? If so, he was not<br />

alone in dereliction of duty. What was<br />

going on that so many did not rush to<br />

help comrades in peril?<br />

In Paul Harvey’s words, give us “the<br />

rest of the story.” Otherwise, we learn<br />

what happened but not why it happened.<br />

Hooker tells us, “<strong>Army</strong> leaders worked<br />

hard to circulate lessons learned and today,<br />

those lessons are taught throughout<br />

our service.” Please share the lessons<br />

with those of us no longer in uniform.<br />

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Steve Kohn,<br />

USA Ret.<br />

San Antonio<br />

Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, USA Ret.<br />

President and CEO, AUSA<br />

Lt. Gen. Guy C. Swan III, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Education, AUSA<br />

Rick Maze<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Liz Rathbun Managing Editor<br />

Joseph L. Broderick Art Director<br />

Ferdinand H. Thomas II Sr. Staff Writer<br />

Toni Eugene<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Christopher Wright Production Artist<br />

Laura Stassi Assistant Managing Editor<br />

Thomas B. Spincic Assistant Editor<br />

Jennifer Benitz<br />

Staff Writer<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.;<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.; Lt.<br />

Gen. Daniel P. Bolger, USA Ret.; and<br />

Brig. Gen. John S. Brown, USA Ret.<br />

Contributing Writers<br />

Scott R. Gourley and Rebecca Alwine<br />

Lt. Gen. Jerry L. Sinn, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Finance and<br />

Administration, AUSA<br />

Desiree Hurlocker<br />

Advertising Production and<br />

Fulfillment Manager<br />

ARMY is a professional journal devoted to the advancement<br />

of the military arts and sciences and representing the in terests<br />

of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>. Copyright©2016, by the Association of<br />

the United States <strong>Army</strong>. ■ ARTICLES appearing in<br />

ARMY do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the officers or<br />

members of the Council of Trustees of AUSA, or its editors.<br />

Articles are expressions of personal opin ion and should not<br />

be interpreted as reflecting the official opinion of the Department<br />

of Defense nor of any branch, command, installation<br />

or agency of the Department of Defense. The magazine<br />

assumes no responsibility for any unsolicited material.<br />

■ ADVERTISING. Neither ARMY, nor its pub lisher, the<br />

Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>, makes any representations,<br />

warranties or endorsements as to the truth and accuracy<br />

of the advertisements appearing herein, and no such<br />

representations, warranties or endorsements should be implied<br />

or inferred from the appearance of the advertisements<br />

in the publication. The advertisers are solely responsible<br />

for the contents of such advertisements. ■<br />

RATES. Individual memberships payable in advance are<br />

(one year/three years): $21/$63 for E1-E4, cadets/OCS and<br />

GS1-GS4; $26/$71 for E5-E7, GS5-GS6; $31/$85 for E8-<br />

E9, O1-O3, W1-W3, GS7-GS11 and veterans; $34/$93 for<br />

O4-O6, W4-W5, GS12-GS15 and civilians; $39/$107 for<br />

O7-O10, SES and ES; life membership, graduated rates to<br />

$525 based on age; $17 a year of all dues is allocated for a<br />

subscription to ARMY magazine. Single copies are $3 except<br />

for the $20 October Green Book edition. For other rates,<br />

write Fulfillment Manager, Box 101560, Arlington, VA<br />

22210-0860.<br />

703-236-2929<br />

Institute of Land<br />

Warfare,<br />

Senior Fellows<br />

703-841-3505<br />

ARMY Magazine,<br />

AUSA News,<br />

Communications<br />

703-841-1050<br />

Executive Office<br />

703-236-2927<br />

Regional Activities,<br />

NCO/Soldier<br />

Programs<br />

703-236-2926<br />

Education,<br />

Family<br />

Programs<br />

ADVERTISING. Information and rates available<br />

from AUSA’s Advertising Production Manager or:<br />

Andrea Guarnero<br />

Mohanna Sales Representatives<br />

305 W. Spring Creek Parkway<br />

Bldg. C-101, Plano, TX 75023<br />

972-596-8777<br />

Email: andreag@mohanna.com<br />

703-243-2589<br />

Industry Affairs<br />

703-841-1442<br />

Administrative<br />

Services<br />

703-841-5101<br />

Information<br />

Technology<br />

703-525-9039<br />

Finance,<br />

Accounting,<br />

Government<br />

Affairs<br />

703-841-7570<br />

Marketing,<br />

Advertising,<br />

Insurance<br />

ARMY (ISSN 0004-2455), published monthly. Vol. 66, No. 2.<br />

Publication offices: Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201-3326, 703-841-<br />

4300, FAX: 703-841-3505, email: armymag@ausa.org. Visit<br />

AUSA’s website at www.ausa.org. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

Arlington, Va., and at additional mailing office.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ARMY Magazine,<br />

Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 3

Seven Questions<br />

For Female Veterans in Texas, There’s H.O.P.E.<br />

Retired <strong>Army</strong> Lt. Col. Hope Jackson is the founder of H.O.P.E.<br />

Institute, a Texas-based nonprofit organization dedicated to helping<br />

homeless female veterans become self-sufficient and independent by<br />

offering housing, education and other services. The acronym stands<br />

for healing, optimizing, perfecting and empowering.<br />

1. Why did you create H.O.P.E. Institute?<br />

I was about 20 years into my career when I got to Fort Bliss in<br />

2006. I was ready to retire here. It struck<br />

my spirit—that here we are next to one of<br />

the largest and fastest-growing military<br />

installations in the world, and there’s<br />

nothing for [homeless] female veterans. I<br />

purchased a home to house homeless female<br />

veterans. That’s how H.O.P.E. Institute<br />

was born. We received 501(c)(3)<br />

status in June 2012.<br />

2. What is H.O.P.E. Institute’s mission?<br />

Our focus is homeless female veterans.<br />

Of the nearly 22 million veterans in this<br />

country, around 2.1 million are women.<br />

Of that population, almost 5 percent are<br />

homeless. What you have to keep in mind<br />

is, that only accounts for the female veterans<br />

who identify as homeless, because<br />

there are still some out there who we don’t<br />

know about yet.<br />

Something’s wrong with that picture.<br />

Retired Lt. Col. Hope Jackson<br />

That could have been any of us given different<br />

circumstances, maybe different<br />

choices, maybe different exposures. So the focus today is to<br />

serve those who gave of themselves so selflessly and now can’t<br />

find a place to call home. Those numbers, this situation, isn’t<br />

going to go away because women are still raising their right<br />

hand to serve and defend.<br />

3. What services does the institute provide?<br />

Every veteran’s needs will be different. When a woman<br />

comes in, she and I will sit down and put together what I call<br />

an individual development plan, which is really her road map<br />

for success. I want the resident to identify what she defines as<br />

success. When she tells me what she wants to do in the next<br />

phase of her life, then we will put together a road map to get<br />

her from where she is to where she deserves to be. It is a selfgoverning<br />

program.<br />

The first 30 days is an acclimation period. There are not going<br />

to be any passes. We are going to go through everything in<br />

terms of their finances, to see if they’re getting all of the benefits<br />

that they are entitled to. We have a job placement program in<br />

place. We’re partners with an organization that has an online<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Sgt. Adam Garlington<br />

platform for higher education that caters to the military. Any<br />

woman coming into the program will get her education through<br />

this organization for free.<br />

<strong>On</strong>e thing that is critically important to understand is that<br />

this isn’t a place where these ladies can come in, go back out,<br />

and continue along the same path that they were on before they<br />

came in. This is a place that is about changing lives. They just<br />

lack the resources, the mentorship and the leadership to help<br />

them make that transition.<br />

4. Are there specific qualifications for<br />

these services?<br />

Yes. First, they must be a veteran. In order<br />

to prove that, I just need a DD-214<br />

[certificate of release or discharge from active<br />

duty] and a VA identification card. It<br />

doesn’t matter their discharge status because<br />

this is a no-judgment zone. We take<br />

you how you come. If you are willing to<br />

work hard to get back on your feet, to have<br />

a life you’ve chosen and your version of the<br />

American dream, we’re here to help.<br />

5. How is the institute funded?<br />

I give presentations around the city to<br />

social and civic organizations and as a result,<br />

many of those groups make donations<br />

to the institute. Citizens in the community<br />

sometimes make small donations, and the<br />

rest comes from me.<br />

6. What does H.O.P.E. Institute need<br />

to continue?<br />

Funding, funding, funding is what we need to run a facility like<br />

this. This is a home, just like you and I live in. My military training<br />

has taught me that the smaller the group, the larger the<br />

chance for success. This is a four-bedroom home that has been<br />

completely renovated. Each room houses two women, so we are<br />

working with groups of six to eight women. It takes resources to<br />

provide food, keep the lights on, pay the water bill. We’re looking<br />

at anywhere from $9,000 to $10,000 a month to keep the house<br />

operational. So that’s how people can help. They can go to our<br />

website at www.theinstituteofhope.org and make donations.<br />

7. What do you hope the institute will accomplish in the future?<br />

The flagpole is here in El Paso, Texas, but the needs of female<br />

veterans are expanding around the entire country. I see<br />

H.O.P.E. Institute being a household name over the next five to<br />

10 years. Anywhere that there’s a large population of female veterans<br />

combined with a military installation, H.O.P.E. Institute<br />

will have a footprint. We are here to change lives, one duty station<br />

at a time.<br />

—Jennifer Benitz<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 5

Washington Report<br />

Congress Urged to Approve More Base Closings<br />

An <strong>Army</strong> that has readiness as its top priority cannot afford<br />

to waste money maintaining excess infrastructure, a panel of<br />

<strong>Army</strong> installation officials has warned Congress.<br />

In a renewed plea for Congress to approve another round of<br />

base closings, Lt. Gen. David D. Halverson, commanding<br />

general, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Installation Management Command, and<br />

assistant chief of staff for installation management, said the<br />

estimated $480 million a year spent maintaining unneeded facilities<br />

would be better spent on training and readiness of<br />

troops or on addressing deferred maintenance and upkeep of<br />

facilities that are needed.<br />

“Fiscal realities are showing in the decline in our facilities,<br />

and it is affecting our future readiness,” Halverson told a<br />

House Armed Services Committee panel in early December.<br />

Having that half-billion dollars from excess bases for other<br />

purposes would help the <strong>Army</strong>, he said. “That would buy a<br />

lot of readiness, and it would also focus our efforts that we<br />

need for investment purposes.” He listed improvements in<br />

ranges as one of the top readiness priorities.<br />

“Persistent funding constraints and the cumulative rising<br />

costs of energy, construction, water and engineering services<br />

have forced the <strong>Army</strong> to take risks in installations to maintain<br />

the ready force,” Halverson said.<br />

The withdrawal of significant combat forces from overseas<br />

has an impact on domestic bases, he said. “We never had the<br />

full force at home station at the same time,” he said. Having<br />

everyone home and in need of postwar training to restore<br />

readiness has led to complications, such as scheduling time on<br />

ranges. With increased demand, planning is more complicated.<br />

With tight funding, training rotations are sometimes<br />

taking longer, making scheduling even more difficult, he said.<br />

Col. Andrew Cole Jr., garrison commander at Fort Riley,<br />

Kan., said <strong>Army</strong> posts are suffering from years of underfunding,<br />

having to pay for standard maintenance versus restoration<br />

and modernization. “We make choices, and we make some decisions,”<br />

he said. “Ultimately, if there is a catastrophic failure,<br />

then we have to end up allocating our funding against that.”<br />

An example, he said, was a leak in the heating and cooling<br />

system of a historic building that likely was the result of not<br />

spending money on adequate preventive checks. The leak<br />

caused significant damage over three floors of the building.<br />

Halverson said the <strong>Army</strong> is filled with other examples, like<br />

how problems with air conditioning in hot locations can lead<br />

to mold and health issues.<br />

Congress is not ready to accept additional base closings and<br />

has flatly denied spending any Pentagon money for planning<br />

closures. However, the 2016 National Defense Authorization<br />

Act includes a provision calling on DoD and the services to submit<br />

a 2017 comprehensive inventory of worldwide installations,<br />

looking at current and future needs. They want to see a 20-year<br />

force structure plan to avoid shutting down bases that might be<br />

excess today but could be needed in the future. Additionally, the<br />

Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of<br />

Congress, is working on a report about excess infrastructure,<br />

with the intention of assessing the value of keeping more posts<br />

and installations than needed to provide surge capacity.<br />

Funding Bill Includes $122 Billion for <strong>Army</strong><br />

The battle over the fiscal year 2016 budget concluded with<br />

an elusive compromise after President Barack Obama on<br />

Dec. 18 signed into law a $1.1 trillion spending bill that included<br />

$514 billion in basic defense spending plus $59 billion<br />

for overseas contingency operations, a $26 billion increase<br />

over the fiscal year 2015 budget.<br />

The Pentagon, White House and Congress will get to do<br />

the whole thing all over again for FY 2017, which begins Oct.<br />

1, 2016. Passing a 2017 budget will be even more complicated<br />

because it is a presidential election year, when politicians<br />

find it difficult to reach any compromise.<br />

The spending levels in the FY 2016 Omnibus Appropriations<br />

Act match a bipartisan agreement made in October. The<br />

measure, combining discretionary spending for all federal agencies<br />

into one bill, was the last significant piece of legislation<br />

Congress had to pass in 2015 before going home for the year.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong>’s share of the budget is about $122 billion, excluding<br />

money for contingency operations. The FY 2017<br />

<strong>Army</strong> budget is expected to be only 2.2 percent larger.<br />

The agreement includes $129 billion for military personnel,<br />

a $1.2 billion increase over FY 2015. Operations and<br />

maintenance spending increase by $5.8 billion, to $167.5 billion<br />

for FY 2016. There are large increases for procurement<br />

and research programs. Procurement spending is $110 billion<br />

for 2016, a $17 billion increase over the 2015 budget. Funding<br />

of research and development programs is $69.8 billion for<br />

FY 2016, a $6.1 billion increase.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong>’s share is $53.5 billion for active, National<br />

Guard and <strong>Army</strong> Reserve personnel; and $41.7 billion in the<br />

base budget for operations and maintenance. For procurement,<br />

the compromise gives the <strong>Army</strong> $5.9 billion for aircraft,<br />

$1.9 billion for tracked vehicles, $1.6 billion for missiles,<br />

$1.2 billion for ammunition, and $5.7 billion for other<br />

procurement. The <strong>Army</strong> also receives $7.5 billion for research,<br />

development, test and evaluation; and $1.5 billion for<br />

military construction and family housing.<br />

6 ARMY ■ February 2016

News Call<br />

Animal-Assisted Therapy Can Help With PTSD<br />

Animal-assisted therapy is offering<br />

an alternative or supplement to the<br />

cognitive processing and prolonged exposure<br />

therapies currently in use to<br />

help military veterans who suffer from<br />

nightmares, depression and other effects<br />

of post-traumatic stress disorder.<br />

The trauma-focused talk therapies have<br />

been known to help, but as a study recently<br />

published in the Journal of the<br />

American Medical Association notes, “nonresponse<br />

rates have been high.” Some<br />

PTSD patients, for example, find the<br />

therapy so upsetting that they drop out.<br />

Dogs have served soldiers for decades<br />

and have proven helpful in easing PTSD.<br />

Horses have helped, too. Brooke <strong>Army</strong><br />

Medical Center in San Antonio offers<br />

equine-assisted therapy. So do VA facilities<br />

in Bedford, Mass., and Albany,<br />

N.Y. In 2010, retired Lt. Col. Bridget<br />

Kroger founded her own organization.<br />

After equine therapy helped her recover<br />

from PTSD, the 24-year <strong>Army</strong> veteran,<br />

who served two tours in Iraq, established<br />

the Wounded Warrior Equestrian<br />

Program to help riding facilities<br />

and horse-rescue farms provide services<br />

to service members and veterans around<br />

the country.<br />

Patrick Bradley, a Vietnam veteran<br />

who suffered from PTSD, recognized<br />

the symptoms when his son Skyler left<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> after more than a decade in<br />

uniform and multiple tours in Iraq and<br />

Afghanistan. Bradley, director of the<br />

raptor program at a Florida nature park,<br />

persuaded his son to visit him at work.<br />

Skyler Bradley found peace among the<br />

wounded birds of prey and soon was<br />

spending a lot of time at the park. He<br />

also began training the birds.<br />

Together, the Bradleys established the<br />

Avian Veteran Alliance and have teamed<br />

with the local VA center where Skyler<br />

was once a patient. Veterans visit the<br />

park twice a week to work with wounded<br />

raptors, and Patrick Bradley takes the<br />

birds to the VA center each month.<br />

Matthew Simmons, who served in<br />

Operations Desert Storm and Desert<br />

Shield, directs operations at the Serenity<br />

Park Parrot Sanctuary on the West Los<br />

Angeles VA campus. His wife, clinical<br />

psychologist Lorin Lindner, founded the<br />

park in 2005. It adopts sick, wounded<br />

and abandoned parrots and lets wounded<br />

warriors care for and establish relationships<br />

with them.<br />

Simmons and Lindner also established<br />

the Lockwood Animal Rescue Center<br />

north of Los Angeles in 2011. It shelters<br />

and rehabilitates wolves and wolf dogs<br />

from around the U.S. and pairs them<br />

with veterans who suffer from PTSD.<br />

Research has shown that touching an<br />

animal can lower blood pressure, relieve<br />

stress and reduce anxiety. As veterans<br />

work with and care for the animals, they<br />

build confidence and self-esteem as well<br />

as accept responsibility.<br />

—Toni Eugene<br />

Staff Sgt. Cedric Richardson rides Gary the horse at the Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston<br />

Equestrian Center. Riding is part of the Soldier Adaptive Reconditioning Program at Brooke <strong>Army</strong><br />

Medical Center.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Warns: Be Vigilant Against <strong>On</strong>line Scams<br />

This Valentine’s Day, you might be<br />

someone’s sweetheart and not even know<br />

it. That’s because imposter accounts online<br />

have proliferated. No one is immune;<br />

as Gen. John F. Campbell, commander<br />

of Resolute Support and U.S. Forces-<br />

Afghanistan, posted on his official Facebook<br />

page about this time last year: “The<br />

intent of this page is to inform readers<br />

about activities here in Afghanistan. Unfortunately,<br />

there are individuals who<br />

copy the photos and comments from this<br />

page and create fake pages using my<br />

name to find romance and/or try to scam<br />

people out of money.”<br />

The post also noted that in the six<br />

months prior, more than 700 fake sites in<br />

Campbell’s name had been identified.<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Criminal Investigation<br />

Command has already warned people<br />

involved in online dating to “proceed<br />

with caution when corresponding with<br />

persons claiming to be U.S. soldiers currently<br />

serving in Afghanistan or elsewhere.”<br />

In addition, the <strong>Army</strong> recently<br />

released a tip sheet for soldiers to reduce<br />

the chances that their names and images<br />

will be appropriated by scammers.<br />

“Imposter Accounts, Romance Scams,<br />

and Unofficial Sites” suggests soldiers<br />

take the following steps to reduce their<br />

vulnerability:<br />

■ Conduct routine searches on social<br />

media platforms for your name; public<br />

affairs professionals should also search<br />

for the names of senior leaders they rep-<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Lori Newman<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 7

esent. Be sure to search using similar<br />

spellings; imposters often use these to<br />

remain undetected.<br />

■ Set up a Google alert (www.google.<br />

com/alerts) for your name and the names<br />

of leaders you represent in an official capacity.<br />

This notification service sends<br />

emails when it finds new results—including<br />

web pages and blogs—that match<br />

the given search terms.<br />

■ Ensure privacy settings are set to<br />

the highest available for professional as<br />

well as personal accounts.<br />

The tip sheet warns that it can be difficult<br />

to remove fake accounts without<br />

proof of identity theft or scam. It also offers<br />

links for reporting imposters on Facebook,<br />

Twitter and Instagram: www.<br />

facebook.com/help/17421051939,<br />

https://support.twitter.com/forms/<br />

impersonation and https://help.instagram.<br />

com/contact/636276399721841.<br />

For more information about identifying<br />

and reporting fake accounts on social<br />

media or dating sites, go to www.army.mil/<br />

media/socialmedia.<br />

New Undersecretary Utilizing<br />

His Service in <strong>Army</strong>, Congress<br />

The new undersecretary of the <strong>Army</strong><br />

said he believes his experiences as an<br />

Iraq War veteran and member of Congress<br />

will help him in the job.<br />

Patrick Murphy, a former <strong>Army</strong> captain<br />

and staff judge advocate, spent eight<br />

years in uniform. He deployed to Bosnia<br />

in 2002 and Iraq in 2003, and also served<br />

as a constitutional law professor at the<br />

U.S. Military Academy. The 42-year-old<br />

served two terms in the U.S. House representing<br />

Pennsylvania’s 8th District.<br />

Murphy was confirmed by the Senate<br />

in a voice vote on Dec. 18, a few days after<br />

appearing before the Senate Armed<br />

Services Committee alongside the nominees<br />

for Air Force and Navy undersecretaries.<br />

Murphy told the committee<br />

that if he were confirmed for the post<br />

that makes him the <strong>Army</strong>’s chief management<br />

officer, he would engage in a<br />

top-to-bottom review looking for “efficiencies<br />

within the organization so we<br />

can refocus on those warfighters who are<br />

keeping our families safe.”<br />

“I will make sure that the <strong>Army</strong> is<br />

manned, trained and equipped to accomplish<br />

what [<strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff]<br />

Gen. [Mark A.] Milley recently articu-<br />

SoldierSpeak<br />

<strong>On</strong> Helmets<br />

“Until I took this job, I had no idea what went into making this equipment, and it’s<br />

been eye-opening,” said Col. Dean M. Hoffman IV of Program Executive Office-<br />

Soldier at Fort Belvoir, Va. “Every helmet is tested probably 67 times. We take<br />

each lot that comes off the production line. We keep some, and we put them in extreme<br />

cold, hot; and constantly every year, we’re pulling them off the shelf and<br />

retesting them to make sure they’re the best.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Clearing Drop Zones<br />

“The bittersweet is my personal archenemy,” said Ben Amos, Integrated Training<br />

Area Management coordinator at Fort Devens, Mass., about the Oriental Bittersweet,<br />

an invasive species. “It’s a very rapidly growing vine that chokes out trees. It<br />

spreads like wildfire. Not only are you going to begin losing trees, which impacts<br />

the habitat, but you have dead trees falling into landing zones, dead branches<br />

falling onto people trying to train, and just basic maneuver impacts.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> A Female Soldier’s Worth<br />

“Female military members’ remarkable service in Iraq and Afghanistan showed that<br />

no military can achieve its full potential without utilizing the talents and abilities of<br />

its female citizens,” said Maj. Gen. David S. Baldwin, adjutant general of the California<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National Guard, before meeting with state legislators and Guard<br />

leaders to discuss the opening of all military occupations to women. “Rescinding all<br />

combat restrictions was more than a move toward equality, but a tactical advancement<br />

as well.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Fighting Spirit<br />

“If you can’t fight and win, then I don’t want you on the team,” said Sgt. 1st Class<br />

Matt Torres of Fort Bragg, N.C., during a leadership seminar at Fort Leavenworth,<br />

Kan. He worries some NCOs have become stagnant in their careers and are willing to<br />

“sit back and chill” while waiting for retirement.<br />

<strong>On</strong> Turkey Jerky<br />

“To see soldiers eat and like something that you have developed, and see that it<br />

improves their morale and helps them perform their mission better—I think that is<br />

the most fulfilling my job as a researcher can get,” said Dr. Tom Yang, a food<br />

technologist at the Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering<br />

Center’s Combat Feeding Directorate in Massachusetts. He helped develop<br />

turkey jerky and turkey bacon for soldiers, using inexpensive technology and creating<br />

food that “has much less salt and stays moist.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Mama Bears<br />

“If you thought the enemy was bad in Afghanistan, wait until my mother finds out<br />

you’re sending me to Texas,” said medically retired Capt. Florent “Flo” Groberg,<br />

recalling when <strong>Army</strong> officials said they might send him to San Antonio Military<br />

Medical Center to recover from severe injuries after he thwarted a suicide bomber<br />

in Kunar Province, Afghanistan, in 2012. Groberg, who earned the Medal of Honor<br />

for his actions, wound up at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, near his<br />

family’s home in Maryland. He spent almost three years recovering.<br />

<strong>On</strong> Giving Back<br />

“If we get wings, it’s an extra bonus,” said Staff Sgt. Micheal Tkachenko of the<br />

65th Military Police Company, Fort Bragg, N.C. “But it’s more or less about just<br />

being able to participate and give back.” Tkachenko waited in line about 26 hours<br />

to donate a toy and be first to win a chance to jump with a partner-nation jumpmaster<br />

and earn foreign jump wings, in the 18th annual Randy Oler Memorial Operation<br />

Toy Drop. Since inception, the toy drop has collected more than 100,000<br />

toys for underprivileged children.<br />

8 ARMY ■ February 2016

COMMAND SERGEANTS MAJOR and SERGEANTS MAJOR CHANGES*<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. J.A. Castillo<br />

from 19th ESC,<br />

Camp Henry, Korea,<br />

to ACC, RA, Ala.<br />

Sgt. Maj. R.J.<br />

Dore from USA<br />

Adjutant General<br />

Sgt. Maj., Fort<br />

Knox, Ky., to<br />

Forces Cmd. G-1,<br />

Fort Bragg, N.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. E.C. Dostie<br />

from USARJ and I<br />

Corps (Forward),<br />

Camp Zama, Japan,<br />

to ARCENT, Shaw<br />

AFB, S.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. C.A. Fagan<br />

from 101st Airborne<br />

Div. Artillery<br />

(Air Assault), Fort<br />

Campbell, Ky., to<br />

FCoE, Fort Sill, Okla.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.A. Ferrusi<br />

from 3rd Bde., 10th<br />

Mountain Div., Fort<br />

Polk, La., to USARAK,<br />

JB Elmendorf-<br />

Richardson, Alaska.<br />

Sgt. Maj. D. Gibbs<br />

from HQ, USASOC,<br />

Fort Bragg, to<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj., USAJFKSWCS,<br />

Fort Bragg.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.B. Manis<br />

from 205th Infantry<br />

Bde., Camp Atterbury,<br />

Ind., to First<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Division East,<br />

Fort Knox.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. D.L. Pinion<br />

from 3rd Squadron,<br />

1st U.S. Cavalry Rgt.,<br />

Fort Benning, Ga., to<br />

Sgt. Maj., USAREUR<br />

G-3, Wiesbaden,<br />

Germany.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.J. Rhoades<br />

from 21st TSC,<br />

Kaiserslautern,<br />

Germany, to<br />

Sgt. Maj., ACSIM,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Command Sgt. Maj.<br />

A.T. Stoneburg<br />

from RRS to USAREC,<br />

Fort Knox.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.A. Torres<br />

from 1st MEB, Fort<br />

Polk, to 13th SC (E),<br />

Fort Hood, Texas.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.F. Watson<br />

from Fort Belvoir<br />

Community<br />

Hospital, Fort<br />

Belvoir, Va., to<br />

PRMC, Honolulu.<br />

■ ACC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Contracting Cmd.; ACSIM—<strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff Installation Management Cmd.; AFB—Air Force Base; ARCENT—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Central; Bde.—Brigade;<br />

ESC—Expeditionary Sustainment Cmd.; FCoE—Fires Center of Excellence; HQ—Headquarters; JB—Joint Base; MEB—Maneuver Enhancement Bde.; PRMC—Pacific Regional<br />

Medical Cmd.; RA—Redstone Arsenal; Rgt.—Regiment; RRS—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Recruiting and Retention School; SC (E)—Sustainment Cmd. (Expeditionary); TSC—Theater<br />

Sustainment Cmd.; USA—U.S. <strong>Army</strong>; USAJFKSWCS—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School; USARAK—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Alaska; USAREC—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Recruiting Cmd.; USAREUR—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe; USARJ—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Japan; USASOC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Special Operations Cmd.<br />

*Command sergeants major and sergeants major positions assigned to general officer commands.<br />

U.S. House of Representatives<br />

Patrick Murphy<br />

lated as his fundamental task: to win in<br />

the unforgiving crucible of ground combat,”<br />

he said. “And I’ll make sure that<br />

our troops do not have a fair fight, that<br />

they have a tactical and technical advantage<br />

against our enemies.”<br />

Murphy told the committee that when<br />

he left Congress five years ago, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

had “45 brigade combat teams on active<br />

duty. We are now down to 31.”<br />

Resources are another concern, he<br />

said, noting the tradeoff the <strong>Army</strong> is<br />

making in slowing modernization to<br />

pay for readiness.<br />

Neera Tanden, president of the Center<br />

for American Progress, said “the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> and the nation are lucky” to have<br />

Murphy confirmed. The former senior<br />

fellow “contributed greatly to our work<br />

by leading on issues that affect 21st-century<br />

fighters, and he will no doubt do<br />

the same for the <strong>Army</strong>,” Tanden said.<br />

Briefs<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Takes Over as Chair of<br />

Conference of American Armies<br />

This month, the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> becomes<br />

chairman of the Conference of American<br />

Armies, a group of 20 member armies,<br />

five observer armies and two international<br />

military organizations from Central,<br />

South and North America that have<br />

met since 1960 to exchange defense ideas<br />

and plan conferences and exercises.<br />

The chairmanship rotates every two<br />

GENERAL<br />

OFFICER<br />

*CHANGES*<br />

Maj. Gen. J.<br />

Caravalho Jr. from<br />

Dep. Surgeon Gen.<br />

and Dep. CG (Spt.),<br />

MEDCOM, Falls<br />

Church, Va., to Jt.<br />

Staff Surgeon, Jt.<br />

Staff, Washington,<br />

D.C.<br />

Brigadier Generals: R.J. Place from Asst. Surgeon<br />

Gen. for Quality and Safety (P), OSG, and Dep. CoS,<br />

Quality and Safety (P), MEDCOM, Washington, D.C.,<br />

to CG, RHC-A (P), Fort Belvoir, Va.; R.D. Tenhet<br />

from CG, RHC-A (P), Fort Belvoir, to Dep. Surgeon<br />

Gen. and Dep. CG (Spt.), MEDCOM, Falls Church.<br />

■ CoS—Chief of Staff; Jt.—Joint; MEDCOM—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Medical Cmd.; OSG—Office of the Surgeon<br />

General; (P)—Provisional; RHC-A—Regional Health<br />

Cmd.-Atlantic; Spt. —Support.<br />

*Assignments to general officer slots announced by<br />

the General Officer Management Office, Department<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong>. Some officers are listed at the<br />

grade to which they are nominated, promotable or<br />

eligible to be frocked. The reporting dates for some<br />

officers may not yet be determined.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 9

West Named <strong>Army</strong> Surgeon General<br />

Maj. Gen. Nadja West is sworn in as the <strong>Army</strong>’s<br />

44th surgeon general and commanding general<br />

of U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Command by acting<br />

Secretary of the <strong>Army</strong> Eric Fanning. As part of<br />

her new assignment, West will be promoted to<br />

lieutenant general, the first African-American<br />

woman in the <strong>Army</strong> to hold the rank. She succeeds<br />

Lt. Gen. Patricia D. Horoho, who retired.<br />

years; this is first time in 24 years that it<br />

has fallen to the U.S.<br />

“Our cooperation over the past 55<br />

years has promoted regional security and<br />

the democratic development of our<br />

member countries,” <strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff<br />

Gen. Mark A. Milley said at the closing<br />

of the group’s 2015 conference in Colombia.<br />

It “provides our armies the opportunity<br />

to increase cooperation and<br />

integration … and, most importantly,<br />

identify the topics of mutual interest in<br />

defense-related matters to develop solutions<br />

that are beneficial to us all.”<br />

DoD: Security in Afghanistan<br />

Deteriorated Last Half of ’15<br />

DoD has acknowledged in a recent<br />

report, “Enhancing Security and Stability<br />

in Afghanistan,” that “the overall security<br />

situation in Afghanistan deteriorated”<br />

in the second half of 2015, “with<br />

an increase in effective insurgent attacks<br />

and higher ANDSF [Afghan National<br />

Defense and Security Forces] and Taliban<br />

casualties.” The report, the second<br />

mandated by Congress in the National<br />

Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal<br />

Year 2015, covers the period from June<br />

1 through Nov. 30.<br />

“Fighting has been nearly continuous<br />

since February 2015,” the report says.<br />

SENIOR EXECUTIVE SERVICE<br />

ANNOUNCEMENTS<br />

R. Kazimer, Tier 2, from<br />

Dir., Corporate Info., CIO,<br />

USACE, Washington, D.C.,<br />

to Dep. to the CG, CCoE,<br />

TRADOC, Fort Gordon, Ga.<br />

Tier 1: L. Swan to Dep. Dir., Rapid Capability<br />

Delivery, JIDA, Washington, D.C.<br />

■ CIO—Chief Information Officer; CCoE—<br />

Cyber Ctr. of Excellence; JIDA—Joint Improvised-<br />

Threat Defeat Agency; TRADOC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Training and Doctrine Cmd.; USACE—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Corps of Engineers.<br />

The ANDSF are now capable of clearing<br />

areas of insurgents, but their ability<br />

“to hold areas after initial clearing operations<br />

is uneven [and] they remain<br />

reluctant to pursue the Taliban into<br />

their traditional safe havens.”<br />

In the six-month reporting period, 12<br />

U.S. service members were killed in<br />

Afghanistan, and 40 were wounded in<br />

action. Insider attacks are still a threat,<br />

although the number continues to decline.<br />

Terrorist and insurgent groups—<br />

particularly al-Qaida—and the possible<br />

expansion of extremist groups such as<br />

the Islamic State are threats to progress<br />

as well as security.<br />

U.S. forces in Afghanistan, now<br />

numbering nearly 10,000, are expected<br />

to remain through most of 2016.<br />

Summit Links Soldier<br />

Readiness To Sleep<br />

Fatigue can lead to mistakes, and the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has begun to focus on the importance<br />

of adequate and quality sleep to<br />

soldiers’ performance.<br />

Staff Sgt. Jacob Miller, 2015 Drill<br />

Sergeant of the Year, told attendees at a<br />

sleep summit sponsored by the <strong>Army</strong><br />

Office of the Surgeon General that he<br />

recognized he had put himself and his<br />

soldiers at risk more than once due to<br />

exhaustion after serving long duty<br />

hours. Miller acknowledged that the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has accorded more time for sleep<br />

since then, but he believes more enforcement<br />

of that guidance is needed.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> sleep specialists at the summit<br />

agreed that quality sleep is imperative to<br />

good safety and that more data is needed<br />

to show the link between fatigue and<br />

poor performance. Sleep, they noted, is<br />

a critical element in the <strong>Army</strong>’s Performance<br />

Triad, which also includes activity<br />

and nutrition. The Office of the Surgeon<br />

General is currently conducting<br />

Performance Triad pilot studies.<br />

Sky’s ‘Unraveling’ Earns Praise<br />

From Literary Critics in 2015<br />

Emma Sky, a noted Middle East<br />

expert and contributor to ARMY magazine,<br />

released her memoir, The Unraveling:<br />

High Hopes and Missed Opportunities<br />

in Iraq, last year—and the literary<br />

world took notice.<br />

Her book was named one of The New<br />

York Times’ 100 Notable Books of 2015<br />

and a Times Editors’ Choice, one of the<br />

Financial Times Books of the Year, a<br />

New Statesman [U.K.] Essential Book<br />

of the Year, a Times [U.K.] Book of the<br />

Year, and one of Military Times’ Top 10<br />

Books of the Year. The book was also<br />

shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson<br />

Prize for Nonfiction for 2015.<br />

Sky is the director of Yale University’s<br />

World Fellows program and a senior fellow<br />

at Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global<br />

Affairs. Although initially opposed to<br />

the war, she volunteered to help rebuild<br />

the Iraqi government after Saddam Hussein<br />

was overthrown in 2003.<br />

She served as the Coalition Provisional<br />

Authority’s governorate coordinator<br />

of Kirkuk, Iraq, from 2003 to 2004,<br />

and as Gen. Raymond T. Odierno’s political<br />

adviser from 2007 to 2010. ✭<br />

John Martinez<br />

10 ARMY ■ February 2016

Front & Center<br />

Readiness and Capability Are Intertwined<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

There is no question about readiness<br />

being the prime responsibility of today’s<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leaders. Every public speaker,<br />

report, news column and magazine article<br />

stresses the requirement and commitment<br />

necessary to guarantee combatready<br />

forces to meet the demands of<br />

national security.<br />

I have no argument with that requirement,<br />

having lived with it in every command<br />

assignment from World War II<br />

through the Cold War. But during my<br />

years of senior command, if anyone<br />

asked for a one-word identification of<br />

my prime responsibility, I would have<br />

answered “capability.”<br />

Readiness is the responsibility of combat<br />

and combat support forces that may<br />

be committed immediately to a crisis situation—those<br />

closest to the crisis at the<br />

highest degree of readiness. Battalion and<br />

company commanders bear the brunt,<br />

but platoon and squad leaders are the<br />

front line of action. Squad leaders ensure<br />

each soldier knows his or her job and has<br />

the skills required by his or her MOS.<br />

They also create the confidence and team<br />

spirit essential for combat operations.<br />

Platoon leaders ensure that squad<br />

leaders have done their jobs, then mold<br />

the teams that must be ready to engage<br />

in the tactical tasks they are expected to<br />

perform. Company commanders supervise<br />

and validate readiness training; they<br />

also are responsible for the first rung of<br />

the capability ladder as they exercise the<br />

ability to call for and employ intelligence,<br />

fire support, logistics and coordination<br />

with other companies engaged in combat<br />

operations. They are the principal contributors<br />

to the development of the next<br />

war’s band of brothers.<br />

Battalion and brigade commanders<br />

also supervise readiness, but their primary<br />

concerns are adequate planning and then<br />

directing operations. Requiring their attention<br />

as battle action unfolds are communications<br />

that obtain fire support and<br />

resupply, maintain contact with adjacent<br />

units and higher and lower echelons, and<br />

control the activities of attached units.<br />

Division and corps commanders direct<br />

combat campaigns. They supervise readiness<br />

training during peacetime, but must<br />

presume readiness when ordered to combat.<br />

They direct combat activities, make<br />

decisions essential for sustaining operations,<br />

and ensure their staffs are sustaining<br />

the support requirements of their<br />

subordinate units. They are also responsible<br />

for recommending or requesting<br />

the additional support or resources that<br />

could expedite action or prevent failure.<br />

The highest commands in a theater of<br />

operations are almost completely concerned<br />

with capability. They must assume<br />

the readiness of the forces committed<br />

to them by the services as they plan<br />

their campaigns, guaranteeing mission<br />

success or explaining the risks involved<br />

and recommending steps to alleviate<br />

those risks.<br />

A perfect example of such a requirement<br />

was the request for an additional<br />

corps in the troop list for the Persian<br />

Gulf campaign in 1990–91. The same<br />

responsibility is borne by the Joint<br />

Chiefs of Staff and the Pentagon, where<br />

the ultimate demands of combat operations<br />

must be satisfied.<br />

When a national crisis occurs, the<br />

president is concerned almost exclusively<br />

with capability. After approving the National<br />

Military Strategy and with assurances<br />

by the Joint Chiefs of the adequacy<br />

of forces to accomplish missions appropriate<br />

to that strategy, he or she can confidently<br />

make decisions to achieve political<br />

objectives. When that system works<br />

as designed, we have military operations<br />

like Just Cause in Panama and Desert<br />

Storm in the Persian Gulf. When the<br />

system is not operable, we have had<br />

World War II and three years of losses,<br />

the Bataan Death March and the Battle<br />

of Kasserine Pass while building the<br />

forces necessary to win in Europe and<br />

the Pacific; and we have had Korea and<br />

the infamous Task Force Smith tragedy.<br />

More recently, we have had unsatisfying<br />

results in Iraq and Afghanistan, where<br />

initial successes were squandered by inadequate<br />

or overcommitments and early<br />

withdrawals.<br />

Fulfilling such a national strategy today<br />

would require an <strong>Army</strong> closer to the<br />

780,000 strength of Just Cause and the<br />

Persian Gulf than the 450,000 currently<br />

programmed for the future. It would<br />

also require restoring the Navy and Air<br />

Force of the 1990s and a continuing<br />

modernization of our nuclear deterrent.<br />

We can hope that Congress and our<br />

presidential candidates are aware of<br />

such a need and will provide a budget<br />

that does not require the services to accommodate<br />

a too small number and a<br />

great risk.<br />

■<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret., formerly<br />

served as vice chief of staff of the<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> and commander in chief of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe. He is a senior fellow<br />

of AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Rick Rzepka<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 11

Winning the War We’ve Got, Not the <strong>On</strong>e We Want<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

We need some hard thinking. We<br />

are not winning the war against<br />

al-Qaida and the Islamic State group in<br />

Iraq or Syria, or elsewhere across North<br />

and East Africa, the greater Middle<br />

East, South Asia and beyond. At best,<br />

one might argue that we are holding our<br />

own, but this is far from winning. The<br />

sooner we come to realize this, the more<br />

likely we are to identify a successful way<br />

forward. Calls for reassessment and new<br />

options with respect to the U.S. approach<br />

to this problem—especially in<br />

light of the attacks in San Bernardino,<br />

Calif., Paris and Lebanon, and the<br />

downing of the Russian civilian airliner<br />

in Sinai—have yielded little so far.<br />

The first step to any solution is to<br />

recognize the problem for what it is.<br />

The next is to recognize what has not<br />

worked. <strong>On</strong>ly then can the outlines of<br />

probable solutions emerge. Neither the<br />

“lash out, do something” approach nor<br />

the “stay the course; it’s a long war” approach<br />

will do.<br />

We are facing a global revolutionary<br />

war, with a narrative that resonates with<br />

many. Most strategists are familiar with<br />

revolutions within a state; the near-global<br />

dimension of this revolution makes it different<br />

and more complex. Our enemies<br />

are not mere criminals. They have conquered,<br />

controlled and now govern territory.<br />

As their own strategic documents<br />

describe, their intent is to eject Western<br />

influence from the region, depose apostate<br />

(in their view) governments and redraw<br />

boundaries—as they already have<br />

between Iraq and Syria, ultimately remaking<br />

the map and adjusting the international<br />

order by creating a caliphate<br />

along the lines of the former Ottoman<br />

Empire. This is part of the context<br />

within which to understand our enemies’<br />

ongoing operations and activities,<br />

whether in one of their regional theaters<br />

of operations or against those they consider<br />

the “far enemy”; that is, Europe,<br />

the U.S. and now, Russia.<br />

Other parts of this global revolution<br />

include several power struggles: one between<br />

the Arabs and Persians; another<br />

between Sunni and Shia. Further, this<br />

revolution is an intra-Sunni struggle between<br />

the very small percentage of radical<br />

and violent Sunni Muslims seeking to<br />

redefine the faith of the vast majority of<br />

other Sunni Muslims. While the broad<br />

dimensions of this power struggle are<br />

important to understand, as in any revolution,<br />

the microdynamics of how it<br />

unfolds in each particular area are perhaps<br />

more important. And again, like all<br />

revolutions, this one has not only political<br />

but also social and religious dimensions<br />

to it. The violence our enemies<br />

use is a means to further their revolutionary<br />

ends and prevail in the regional<br />

power struggles.<br />

Finally, the geographic scope of this<br />

revolution’s context makes it an international<br />

problem, not just a regional<br />

one. In fact, one aspect of this revolutionary<br />

movement is to undo the international<br />

order produced after World<br />

War II and sustained throughout the<br />

Cold War. The stability produced by<br />

this order was, in part, a result of nations<br />

primarily resorting to institutions<br />

rather than violence to resolve differences.<br />

Al-Qaida, the Islamic State and<br />

their like reject these institutions, preferring<br />

violence to establish the “order”<br />

they seek. All nations have a stake in<br />

the international system that is under<br />

attack, and those with a bigger stake<br />

have more responsibilities to preserve<br />

and adapt that system.<br />

Several conclusions derive from the<br />

type of war we’re in. First, success in this<br />

war will require a new Western-regional<br />

coalition, one that is committed to sufficiently<br />

common principles and goals and<br />

will follow a common civil-military strategy.<br />

Given the divergence of interests in<br />

the region, no “grand alliance” seems<br />

likely. But a lesser coalition, perhaps<br />

even several bilateral arrangements, may<br />

be possible. Under these conditions, no<br />

rigid universal strategy will work; a more<br />

flexible, general one may.<br />

A precisely defined “end state” may be<br />

the wrong construct to use in this war.<br />

Rather, the strategy will have to be a<br />

combination of creating local successes<br />

that build toward the future the coalition<br />

seeks. And this war cannot be won without<br />

more participation from our Arab allies.<br />

We need to study carefully, learn<br />

from and adapt to the reasons why they<br />

have been hesitant.<br />

Second, ideas and narratives are the<br />

fuel of revolutions, so the main effort of<br />

whatever counterstrategy is adopted<br />

must attack the enemies’ narrative both<br />

by coalition domestic and international<br />

actions. A counternarrative campaign is<br />

not a “spin campaign.” Rather, it stitches<br />

together domestic and international actions<br />

concerning governance, economic,<br />

social and religious policies in ways that<br />

prove our enemies’ narratives wrong, reinforce<br />

the coalition narrative, and show<br />

our enemies for what they really are.<br />

All security actions must support this<br />

main effort. Our current counternarrative<br />

campaign remains weak because<br />

our actions are disjointed and unconnected<br />

to a vision of a future different<br />

from and more compelling than that of<br />

our enemies.<br />

Third, the “tissue” that connects our<br />

enemies is as important as our enemies<br />

themselves. This connective tissue consists<br />

of the means our enemies use to recruit,<br />

radicalize, plan, prepare, execute, finance<br />

and sustain their activities. This<br />

tissue lies in the open space of normal<br />

civil and economic communications flow,<br />

a space controlled by sovereign states and<br />

their security services. We have taken<br />

some action against this “tissue” but after<br />

14 years of war, our actions clearly have<br />

not been sufficiently robust, coordinated<br />

or timely. Whatever coalition is formed<br />

will have to develop domestic and<br />

transnational norms and methods to deal<br />

with this connective tissue.<br />

Fourth, while the “solutions” to this<br />

revolution are clearly local, local governance,<br />

economic, social and religious<br />

policies are as much causative to the rise<br />

of the revolution as are the policies and<br />

actions of “external” powers. So our reassessment<br />

must address the domestic<br />

policies of coalition members that our<br />

enemies are using to their advantage.<br />

Last, the security aspects of whatever<br />

strategy the coalition adopts must include<br />

both military forces and domestic<br />

as well as transnational police forces.<br />

Our enemies operate in the space be-<br />

12 ARMY ■ February 2016

tween crime and war, and between<br />

peace and war. The coalition must close<br />

these spaces.<br />

We have allowed the revolution to<br />

spread. Like the cancer it is, the ground<br />

that this revolutionary enemy controls<br />

and the networks they have established<br />

must be reduced; how and when are the<br />

only questions. Our current efforts to reduce<br />

this threat have been insufficient. In<br />

fact, in the face of our efforts, both enemy-held<br />

territory and their networks<br />

have expanded.<br />

We are fighting a war of attrition, acting<br />

as if time is on our side. It is not.<br />

The main effort—the counterideology<br />

campaign and its governance, economic,<br />

social and religious components—will<br />

not succeed in the current security environment.<br />

So while it is a supporting effort,<br />

successful military and police security<br />

operations are essential. Here, the<br />

coalition faces one of its many hard<br />

choices: Reduce our enemies’ control<br />

and influence—in at least some of the<br />

areas in which our enemies have<br />

grown—using coalition air, ground and<br />

special operations forces in conjunction<br />

with local forces; or pace reduction<br />

upon local security force capacity. The<br />

former option will accelerate the pace of<br />

our current operations but incur one<br />

kind of risk. The latter drags out an already<br />

too-long war, which incurs other<br />

kinds of risks.<br />

This global revolution has been clear<br />

to some for years. Also clear is that the<br />

U.S. strategic approaches used since the<br />

Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks have not<br />

been sufficiently successful. Our enemies<br />

have occasionally been disrupted, parts<br />

have been dismantled; but they have not<br />

been defeated and certainly are not destroyed.<br />

In fact, they have morphed and expanded—despite<br />

14 years of war and billions<br />

of dollars spent, hundreds of “highvalue<br />

targets” and thousands of others<br />

killed, thousands of our own casualties,<br />

tens of thousands civilians dead or<br />

wounded, and hundreds of thousands of<br />

refugees spread throughout the world.<br />

Simply put: While we have had some<br />

successes, neither the expansive, nearunilateral<br />

strategy of the former Bush<br />

administration nor the minimalist, gradualist,<br />

surrogate approach of the Obama<br />

administration has worked. <strong>On</strong>e might<br />

even say that both strategies have used<br />

approaches that have strengthened the<br />

enemies’ narrative and ideology rather<br />

than diminished it. The same can be said<br />

of some of the domestic policies adopted<br />

by nations in as well as out of the region.<br />

Both administrations have treated<br />

coalition members as “contributing<br />

nations,” where contributions are sometimes<br />

combat, advisory or support troops;<br />

and other times funds, equipment, or<br />

other military or nonmilitary capabilities.<br />

This approach can create the illusion of a<br />

multinational effort, but it does not reflect<br />

a serious attempt to align nations<br />

around similar interests and common<br />

goals. Nor does it reflect an attempt to<br />

have coalition partners, together, ascribe<br />

to common principles and develop common<br />

goals and a common strategic approach<br />

to attaining those goals. A more<br />

traditional approach to coalitions would<br />

add legitimacy to the international actions<br />

that are required in waging and<br />

fighting the war against our global revolutionary<br />

enemies.<br />

With rare exception, neither administration<br />

has been able to develop and execute<br />

a set of coherent civil-military strategies,<br />

policies and campaigns. Whether<br />

viewed domestically or internationally, if<br />

the approach so far were a musical score,<br />

it would be described more as cacophony<br />

than harmony. Going forward, we need<br />

not only a better coalition and strategy,<br />

but also better collaborative bodies and<br />

processes to make decisions, take coordinated<br />

action, and adapt faster than our<br />

enemies. We have been, consistently, too<br />

slow.<br />

Where do we go from here? Most important<br />

is to rethink what we’ve been doing.<br />

Intellectual change must precede<br />

any changes in approach. Too much of<br />

our post-9/11 collective action has been<br />

taken in the haste to “do something” or<br />

to demonstrate strength. Too much has<br />

been reactive to the crisis of the day or<br />

has been discrete actions unconnected to<br />

a coherent campaign that, if successful,<br />

will attain strategic aims. And too much<br />

has been done sequentially, not simultaneously.<br />

Further, our reassessment must acknowledge<br />

that in the kind of war we’re<br />

in, “defeat” and “destruction” cannot be<br />

defined in strictly military terms. Bombs,<br />

raids and any other kind of kinetic actions<br />

are necessary, but they are not sufficient<br />

to defeat a revolutionary enemy.<br />

Destruction of a revolution requires<br />

more. Revolutions ignite moral indignation<br />

about one power arrangement,<br />

then maneuver to replace that arrangement<br />

with another promulgated as better.<br />

Bombs and raids do not take the<br />

wind out of the sail of moral indignation.<br />

As long as we act as if defeat or<br />

destruction is a military task, success<br />

will continue to elude us. We need a coherent<br />

set of civil and military strategies,<br />

policies and campaigns, in service<br />

to a broader goal.<br />

Any reassessment worthy of the name,<br />

therefore, must start by answering this<br />

question: What kind of durable political<br />

outcome will actually produce a better<br />

peace? So far, we have heard little in answer<br />

to this question. Members of whatever<br />

coalition that forms must agree at<br />

least to the principles that will guide<br />

them to a satisfactory answer.<br />

The answer to this question is fundamental<br />

because in war, strategies, policies<br />

and campaigns, whether military or nonmilitary,<br />

are merely instruments. Their<br />

value is relative; their worth can be<br />

judged only relative to their capacity to<br />

achieve the end or ends sought. What<br />

are we seeking beyond destruction of our<br />

enemies? The answer to that question<br />

must be compelling and to sustain domestic<br />

and coalition support, our actions<br />

must clearly demonstrate that we are<br />

making progress toward that end.<br />

We cannot define the war to fit our<br />

own biases. Nor can we “spin” it to fit<br />

what we want to do rather than what has<br />

to be done. The worth of whatever<br />

strategies the coalition finally chooses<br />

will be a function of how well those<br />

strategies fit the realities of the war,<br />

whether they attain the common goals at<br />

reasonable costs and time, and how easily<br />

the coalition can adapt as the war unfolds.<br />

We may not like the war we’ve<br />

got, and we may wish things were otherwise,<br />

but success in war results from<br />

dealing with reality as it is. ■<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.,<br />

Ph.D., is a former commander of Multi-<br />

National Security Transition Command-<br />

Iraq and a senior fellow of AUSA’s Institute<br />

of Land Warfare.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 13

Yep, Those Were the Good Old <strong>Army</strong> Days<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

With the <strong>Army</strong> in a time of change,<br />

it is good to look back at the “good<br />

old days.” The <strong>Army</strong> between the two<br />

world wars is the best remembered “Old<br />

<strong>Army</strong>.” The Old <strong>Army</strong> has been called<br />

an athletic club, a school, a home for<br />

wayward youth and a boys’ camp, all<br />

rolled into one.<br />

The Old <strong>Army</strong> was predominately<br />

horse-drawn and very traditional.<br />

When mechanization arrived in<br />

the 1930s and the horses left the<br />

stables, it was more traumatic<br />

than just trading in brown boots<br />

for black ones and campaign<br />

hats for overseas caps. Individual<br />

squad drill was replaced by<br />

massed battalion marching formations;<br />

the M1 Garand rifle<br />

replaced the legendary Springfield<br />

with its Mauser bolt action.<br />

When it came to getting out<br />

of personal debt, there was a<br />

saying in the rural parts of the<br />

country: Don’t sell the farm. It<br />

was understood that if families<br />

could afford to hold on to their<br />

farms, they’d never starve. Also,<br />

government-subsidized life insurance<br />

for soldiers in 1917 was<br />

$10,000—about the same amount as the<br />

average farm mortgage. Thus, when a<br />

soldier was killed, the death payment to<br />

his family “bought the farm.”<br />

Another good old saying at the turn of<br />

the century was by author Hilaire Belloc:<br />

“Whatever happens, we have got the<br />

Maxim gun and they have not.” It was<br />

the Maxim gun and its follow-on derivatives<br />

that allowed English-speaking<br />

countries and France to rule most of the<br />

discovered world. But that lasted only as<br />

long as “we” had it and “they” did not.<br />

With the demise of the Old <strong>Army</strong><br />

went wrap leggings, hand-powered telephones<br />

and signal flags, washpan helmets,<br />