Army - Kicking Tires On Jltv

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

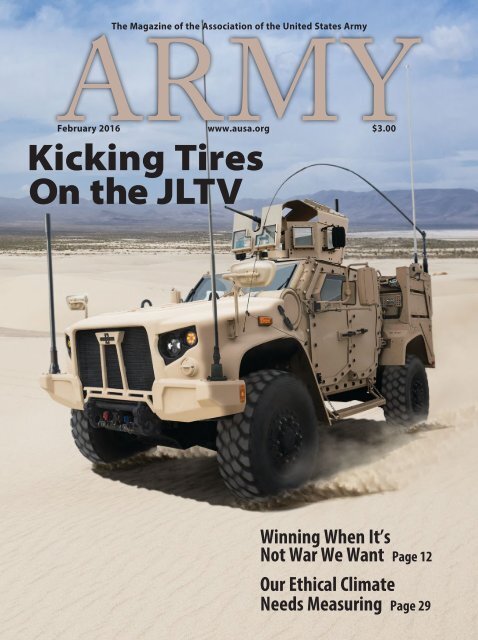

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

ARMY<br />

February 2016 www.ausa.org $3.00<br />

<strong>Kicking</strong> <strong>Tires</strong><br />

<strong>On</strong> the JLTV<br />

Winning When It’s<br />

Not War We Want Page 12<br />

Our Ethical Climate<br />

Needs Measuring Page 29

ARMY<br />

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

February 2016 www.ausa.org Vol. 66, No. 2<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

LETTERS....................................................3<br />

SEVEN QUESTIONS ..................................5<br />

WASHINGTON REPORT ...........................6<br />

NEWS CALL..............................................7<br />

FRONT & CENTER<br />

Readiness and Capability<br />

Are Intertwined<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.<br />

Page 11<br />

Winning the War We’ve Got,<br />

Not the <strong>On</strong>e We Want<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.<br />

Page 12<br />

Yep, Those Were the Good Old<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Days<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, USA Ret.<br />

Page 14<br />

FEATURES<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Women: Highlights<br />

With the announcement lifting gender<br />

restrictions on all military jobs, we take a<br />

pictorial look at the role of female soldiers<br />

throughout U.S. history. Page 18<br />

Cyber Capabilities Key to<br />

Future Dominance<br />

By Lt. Gen. Edward C. Cardon<br />

Unlike the other domains, cyberspace is<br />

continuously evolving and adapting along<br />

with each entrepreneur, inventor and actor<br />

using it. To retain dominance, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

must keep up with this evolution. Page 22<br />

Muscle for an Uncertain World:<br />

Performance, Payload and<br />

Comfy Seats<br />

Stories by Scott R. Gourley<br />

The latest generation of Joint Light<br />

Tactical Vehicles has moved well<br />

beyond the traditional role of <strong>Army</strong><br />

trucks and into the realm of what can<br />

be described as “muscle trucks.”<br />

Page 36<br />

Cover Photo: The independent suspension<br />

system in the Joint Light Tactical<br />

Vehicle allows it to traverse the toughest<br />

terrains.<br />

Oshkosh Corp.<br />

18<br />

14<br />

HE’S THE ARMY......................................17<br />

THE OUTPOST........................................57<br />

SUSTAINING MEMBER PROFILE...........60<br />

SOLDIER ARMED....................................61<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING.....................63<br />

REVIEWS.................................................65<br />

FINAL SHOT ...........................................72<br />

22<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 1

Fighting for Relevancy in the Gray Zone By Maj. David B. Rowland<br />

Successfully responding to conflicts that exist between normal international<br />

competition and open conflict requires the <strong>Army</strong>’s conventional forces to alter<br />

training mentality and methodology. Page 26<br />

Curtain’s Always Rising<br />

For Theater <strong>Army</strong><br />

By Lt. Gen. James L. Terry, USA Ret.<br />

Recent events provide a vehicle for<br />

exploring the versatility of the theater<br />

<strong>Army</strong> in a manner far more dynamic than<br />

its equally important role as an <strong>Army</strong><br />

service component command. Page 49<br />

49<br />

It’s Time to Establish<br />

Ethics-Related Metrics<br />

By Col. Charles D. Allen, USA Ret.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> needs to construct a way to<br />

measure the character of its leaders and<br />

ethics within the profession of arms to<br />

ensure we are “getting it right.” Page 29<br />

Creativity Could Boost<br />

Regionally Aligned Forces Concept<br />

By Col. Allen J. Pepper<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leadership’s vision involves a force<br />

that is globally responsive and regionally<br />

engaged. An important aspect of turning<br />

this vision into reality is the concept of<br />

regionally aligned forces. Page 32<br />

40<br />

Creative Answers for Sagging Morale<br />

By Capt. Robert C. Sprague<br />

<strong>On</strong>e of the most critical ideas to foster<br />

within an organization is innovation;<br />

without it, soldiers are doomed to repeat<br />

the same errors indefinitely. Page 43<br />

The Evolving Art of Training<br />

Management<br />

By Col. David M. Hodne and Maj. Joe Byerly<br />

An evolution in training management is<br />

reflected in current <strong>Army</strong> doctrine and is<br />

fueled by the hard-earned combat<br />

experience of leaders across the <strong>Army</strong>, new<br />

digital training tools, and an institutional<br />

resurgence in Mission Command. Page 45<br />

Birth Era May Factor in Risk<br />

of Suicide<br />

By Col. James Griffith, ARNG Ret.,<br />

and Craig Bryan<br />

The marked increase in soldier suicides may<br />

not be related to deployment, combat<br />

participation or an overall high operating<br />

tempo but instead, an indication of a<br />

broader trend of increased vulnerability<br />

among more recent generations of young<br />

adults. Page 53<br />

53<br />

Deep Roots of the <strong>Army</strong>’s<br />

Dental Corps<br />

By Daniel J. Demers<br />

From its inception in 1901 after Spanish-<br />

American War veterans experienced<br />

extraordinary dental problems, the U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Dental Corps has grown in size, skill<br />

and influence. Page 40<br />

45<br />

2 ARMY ■ February 2016

Letters<br />

Good Mentoring Makes<br />

Good Memories<br />

■ I was delighted to see the article by<br />

retired Maj. Wayne Heard in the December<br />

issue, “Mentoring Stands Test of<br />

Time,” about Col. Robert L. Jackson.<br />

Jackson was a great man, and I owe much<br />

to him. I worked for him when he was<br />

the deputy chief of staff for operations of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Pacific. His counsel, coaching<br />

and friendship helped me through some<br />

very challenging times. Kudos to Heard.<br />

Col. Lawrence E. Casper, USA Ret.<br />

Oro Valley, Ariz.<br />

AUSA FAX NUMBERS<br />

ARMY magazine welcomes letters to<br />

the editor. Short letters are more<br />

likely to be published, and all letters<br />

may be edited for reasons of style,<br />

accuracy or space limitations. Letters<br />

should be exclusive to ARMY magazine.<br />

All letters must include the<br />

writer’s full name, address and daytime<br />

telephone num ber. The volume<br />

of letters we receive makes individual<br />

acknowledgment impossible. Please<br />

send letters to The Editor, ARMY magazine,<br />

AUSA, 2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington,<br />

VA 22201. Letters may also<br />

be faxed to 703- 841-3505 or sent via<br />

email to armymag@ausa.org.<br />

Share Battle of Ganjgal Lessons<br />

■ Another excellent essay by retired<br />

Col. Richard D. Hooker Jr. (“‘Ride to<br />

the Sound of the Guns,’” September).<br />

How does ARMY magazine keep finding<br />

great writers, decade after decade?<br />

But I request a follow-up article on<br />

why so many leaders did not provide<br />

support to the warriors in battle that<br />

day. Why was it necessary for “the <strong>Army</strong><br />

[to act] swiftly to fix responsibility after<br />

the battle, issuing career-ending reprimands<br />

to key leaders judged to have been<br />

at fault”?<br />

We read, for example: “Meanwhile,<br />

the battalion commander [of a unit that<br />

had been radioed for fire support] remained<br />

in his office.” But it seems implausible<br />

for one who has risen to that<br />

position and rank to intentionally repudiate<br />

responsibility.<br />

Had he just returned from an exhausting<br />

patrol and fallen asleep at his desk?<br />

Was he talking to his family back home?<br />

Had he even been made aware of the situation<br />

on the ground? If so, he was not<br />

alone in dereliction of duty. What was<br />

going on that so many did not rush to<br />

help comrades in peril?<br />

In Paul Harvey’s words, give us “the<br />

rest of the story.” Otherwise, we learn<br />

what happened but not why it happened.<br />

Hooker tells us, “<strong>Army</strong> leaders worked<br />

hard to circulate lessons learned and today,<br />

those lessons are taught throughout<br />

our service.” Please share the lessons<br />

with those of us no longer in uniform.<br />

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Steve Kohn,<br />

USA Ret.<br />

San Antonio<br />

Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, USA Ret.<br />

President and CEO, AUSA<br />

Lt. Gen. Guy C. Swan III, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Education, AUSA<br />

Rick Maze<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Liz Rathbun Managing Editor<br />

Joseph L. Broderick Art Director<br />

Ferdinand H. Thomas II Sr. Staff Writer<br />

Toni Eugene<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Christopher Wright Production Artist<br />

Laura Stassi Assistant Managing Editor<br />

Thomas B. Spincic Assistant Editor<br />

Jennifer Benitz<br />

Staff Writer<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.;<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.; Lt.<br />

Gen. Daniel P. Bolger, USA Ret.; and<br />

Brig. Gen. John S. Brown, USA Ret.<br />

Contributing Writers<br />

Scott R. Gourley and Rebecca Alwine<br />

Lt. Gen. Jerry L. Sinn, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Finance and<br />

Administration, AUSA<br />

Desiree Hurlocker<br />

Advertising Production and<br />

Fulfillment Manager<br />

ARMY is a professional journal devoted to the advancement<br />

of the military arts and sciences and representing the in terests<br />

of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>. Copyright©2016, by the Association of<br />

the United States <strong>Army</strong>. ■ ARTICLES appearing in<br />

ARMY do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the officers or<br />

members of the Council of Trustees of AUSA, or its editors.<br />

Articles are expressions of personal opin ion and should not<br />

be interpreted as reflecting the official opinion of the Department<br />

of Defense nor of any branch, command, installation<br />

or agency of the Department of Defense. The magazine<br />

assumes no responsibility for any unsolicited material.<br />

■ ADVERTISING. Neither ARMY, nor its pub lisher, the<br />

Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>, makes any representations,<br />

warranties or endorsements as to the truth and accuracy<br />

of the advertisements appearing herein, and no such<br />

representations, warranties or endorsements should be implied<br />

or inferred from the appearance of the advertisements<br />

in the publication. The advertisers are solely responsible<br />

for the contents of such advertisements. ■<br />

RATES. Individual memberships payable in advance are<br />

(one year/three years): $21/$63 for E1-E4, cadets/OCS and<br />

GS1-GS4; $26/$71 for E5-E7, GS5-GS6; $31/$85 for E8-<br />

E9, O1-O3, W1-W3, GS7-GS11 and veterans; $34/$93 for<br />

O4-O6, W4-W5, GS12-GS15 and civilians; $39/$107 for<br />

O7-O10, SES and ES; life membership, graduated rates to<br />

$525 based on age; $17 a year of all dues is allocated for a<br />

subscription to ARMY magazine. Single copies are $3 except<br />

for the $20 October Green Book edition. For other rates,<br />

write Fulfillment Manager, Box 101560, Arlington, VA<br />

22210-0860.<br />

703-236-2929<br />

Institute of Land<br />

Warfare,<br />

Senior Fellows<br />

703-841-3505<br />

ARMY Magazine,<br />

AUSA News,<br />

Communications<br />

703-841-1050<br />

Executive Office<br />

703-236-2927<br />

Regional Activities,<br />

NCO/Soldier<br />

Programs<br />

703-236-2926<br />

Education,<br />

Family<br />

Programs<br />

ADVERTISING. Information and rates available<br />

from AUSA’s Advertising Production Manager or:<br />

Andrea Guarnero<br />

Mohanna Sales Representatives<br />

305 W. Spring Creek Parkway<br />

Bldg. C-101, Plano, TX 75023<br />

972-596-8777<br />

Email: andreag@mohanna.com<br />

703-243-2589<br />

Industry Affairs<br />

703-841-1442<br />

Administrative<br />

Services<br />

703-841-5101<br />

Information<br />

Technology<br />

703-525-9039<br />

Finance,<br />

Accounting,<br />

Government<br />

Affairs<br />

703-841-7570<br />

Marketing,<br />

Advertising,<br />

Insurance<br />

ARMY (ISSN 0004-2455), published monthly. Vol. 66, No. 2.<br />

Publication offices: Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201-3326, 703-841-<br />

4300, FAX: 703-841-3505, email: armymag@ausa.org. Visit<br />

AUSA’s website at www.ausa.org. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

Arlington, Va., and at additional mailing office.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ARMY Magazine,<br />

Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 3

Seven Questions<br />

For Female Veterans in Texas, There’s H.O.P.E.<br />

Retired <strong>Army</strong> Lt. Col. Hope Jackson is the founder of H.O.P.E.<br />

Institute, a Texas-based nonprofit organization dedicated to helping<br />

homeless female veterans become self-sufficient and independent by<br />

offering housing, education and other services. The acronym stands<br />

for healing, optimizing, perfecting and empowering.<br />

1. Why did you create H.O.P.E. Institute?<br />

I was about 20 years into my career when I got to Fort Bliss in<br />

2006. I was ready to retire here. It struck<br />

my spirit—that here we are next to one of<br />

the largest and fastest-growing military<br />

installations in the world, and there’s<br />

nothing for [homeless] female veterans. I<br />

purchased a home to house homeless female<br />

veterans. That’s how H.O.P.E. Institute<br />

was born. We received 501(c)(3)<br />

status in June 2012.<br />

2. What is H.O.P.E. Institute’s mission?<br />

Our focus is homeless female veterans.<br />

Of the nearly 22 million veterans in this<br />

country, around 2.1 million are women.<br />

Of that population, almost 5 percent are<br />

homeless. What you have to keep in mind<br />

is, that only accounts for the female veterans<br />

who identify as homeless, because<br />

there are still some out there who we don’t<br />

know about yet.<br />

Something’s wrong with that picture.<br />

Retired Lt. Col. Hope Jackson<br />

That could have been any of us given different<br />

circumstances, maybe different<br />

choices, maybe different exposures. So the focus today is to<br />

serve those who gave of themselves so selflessly and now can’t<br />

find a place to call home. Those numbers, this situation, isn’t<br />

going to go away because women are still raising their right<br />

hand to serve and defend.<br />

3. What services does the institute provide?<br />

Every veteran’s needs will be different. When a woman<br />

comes in, she and I will sit down and put together what I call<br />

an individual development plan, which is really her road map<br />

for success. I want the resident to identify what she defines as<br />

success. When she tells me what she wants to do in the next<br />

phase of her life, then we will put together a road map to get<br />

her from where she is to where she deserves to be. It is a selfgoverning<br />

program.<br />

The first 30 days is an acclimation period. There are not going<br />

to be any passes. We are going to go through everything in<br />

terms of their finances, to see if they’re getting all of the benefits<br />

that they are entitled to. We have a job placement program in<br />

place. We’re partners with an organization that has an online<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Sgt. Adam Garlington<br />

platform for higher education that caters to the military. Any<br />

woman coming into the program will get her education through<br />

this organization for free.<br />

<strong>On</strong>e thing that is critically important to understand is that<br />

this isn’t a place where these ladies can come in, go back out,<br />

and continue along the same path that they were on before they<br />

came in. This is a place that is about changing lives. They just<br />

lack the resources, the mentorship and the leadership to help<br />

them make that transition.<br />

4. Are there specific qualifications for<br />

these services?<br />

Yes. First, they must be a veteran. In order<br />

to prove that, I just need a DD-214<br />

[certificate of release or discharge from active<br />

duty] and a VA identification card. It<br />

doesn’t matter their discharge status because<br />

this is a no-judgment zone. We take<br />

you how you come. If you are willing to<br />

work hard to get back on your feet, to have<br />

a life you’ve chosen and your version of the<br />

American dream, we’re here to help.<br />

5. How is the institute funded?<br />

I give presentations around the city to<br />

social and civic organizations and as a result,<br />

many of those groups make donations<br />

to the institute. Citizens in the community<br />

sometimes make small donations, and the<br />

rest comes from me.<br />

6. What does H.O.P.E. Institute need<br />

to continue?<br />

Funding, funding, funding is what we need to run a facility like<br />

this. This is a home, just like you and I live in. My military training<br />

has taught me that the smaller the group, the larger the<br />

chance for success. This is a four-bedroom home that has been<br />

completely renovated. Each room houses two women, so we are<br />

working with groups of six to eight women. It takes resources to<br />

provide food, keep the lights on, pay the water bill. We’re looking<br />

at anywhere from $9,000 to $10,000 a month to keep the house<br />

operational. So that’s how people can help. They can go to our<br />

website at www.theinstituteofhope.org and make donations.<br />

7. What do you hope the institute will accomplish in the future?<br />

The flagpole is here in El Paso, Texas, but the needs of female<br />

veterans are expanding around the entire country. I see<br />

H.O.P.E. Institute being a household name over the next five to<br />

10 years. Anywhere that there’s a large population of female veterans<br />

combined with a military installation, H.O.P.E. Institute<br />

will have a footprint. We are here to change lives, one duty station<br />

at a time.<br />

—Jennifer Benitz<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 5

Washington Report<br />

Congress Urged to Approve More Base Closings<br />

An <strong>Army</strong> that has readiness as its top priority cannot afford<br />

to waste money maintaining excess infrastructure, a panel of<br />

<strong>Army</strong> installation officials has warned Congress.<br />

In a renewed plea for Congress to approve another round of<br />

base closings, Lt. Gen. David D. Halverson, commanding<br />

general, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Installation Management Command, and<br />

assistant chief of staff for installation management, said the<br />

estimated $480 million a year spent maintaining unneeded facilities<br />

would be better spent on training and readiness of<br />

troops or on addressing deferred maintenance and upkeep of<br />

facilities that are needed.<br />

“Fiscal realities are showing in the decline in our facilities,<br />

and it is affecting our future readiness,” Halverson told a<br />

House Armed Services Committee panel in early December.<br />

Having that half-billion dollars from excess bases for other<br />

purposes would help the <strong>Army</strong>, he said. “That would buy a<br />

lot of readiness, and it would also focus our efforts that we<br />

need for investment purposes.” He listed improvements in<br />

ranges as one of the top readiness priorities.<br />

“Persistent funding constraints and the cumulative rising<br />

costs of energy, construction, water and engineering services<br />

have forced the <strong>Army</strong> to take risks in installations to maintain<br />

the ready force,” Halverson said.<br />

The withdrawal of significant combat forces from overseas<br />

has an impact on domestic bases, he said. “We never had the<br />

full force at home station at the same time,” he said. Having<br />

everyone home and in need of postwar training to restore<br />

readiness has led to complications, such as scheduling time on<br />

ranges. With increased demand, planning is more complicated.<br />

With tight funding, training rotations are sometimes<br />

taking longer, making scheduling even more difficult, he said.<br />

Col. Andrew Cole Jr., garrison commander at Fort Riley,<br />

Kan., said <strong>Army</strong> posts are suffering from years of underfunding,<br />

having to pay for standard maintenance versus restoration<br />

and modernization. “We make choices, and we make some decisions,”<br />

he said. “Ultimately, if there is a catastrophic failure,<br />

then we have to end up allocating our funding against that.”<br />

An example, he said, was a leak in the heating and cooling<br />

system of a historic building that likely was the result of not<br />

spending money on adequate preventive checks. The leak<br />

caused significant damage over three floors of the building.<br />

Halverson said the <strong>Army</strong> is filled with other examples, like<br />

how problems with air conditioning in hot locations can lead<br />

to mold and health issues.<br />

Congress is not ready to accept additional base closings and<br />

has flatly denied spending any Pentagon money for planning<br />

closures. However, the 2016 National Defense Authorization<br />

Act includes a provision calling on DoD and the services to submit<br />

a 2017 comprehensive inventory of worldwide installations,<br />

looking at current and future needs. They want to see a 20-year<br />

force structure plan to avoid shutting down bases that might be<br />

excess today but could be needed in the future. Additionally, the<br />

Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of<br />

Congress, is working on a report about excess infrastructure,<br />

with the intention of assessing the value of keeping more posts<br />

and installations than needed to provide surge capacity.<br />

Funding Bill Includes $122 Billion for <strong>Army</strong><br />

The battle over the fiscal year 2016 budget concluded with<br />

an elusive compromise after President Barack Obama on<br />

Dec. 18 signed into law a $1.1 trillion spending bill that included<br />

$514 billion in basic defense spending plus $59 billion<br />

for overseas contingency operations, a $26 billion increase<br />

over the fiscal year 2015 budget.<br />

The Pentagon, White House and Congress will get to do<br />

the whole thing all over again for FY 2017, which begins Oct.<br />

1, 2016. Passing a 2017 budget will be even more complicated<br />

because it is a presidential election year, when politicians<br />

find it difficult to reach any compromise.<br />

The spending levels in the FY 2016 Omnibus Appropriations<br />

Act match a bipartisan agreement made in October. The<br />

measure, combining discretionary spending for all federal agencies<br />

into one bill, was the last significant piece of legislation<br />

Congress had to pass in 2015 before going home for the year.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong>’s share of the budget is about $122 billion, excluding<br />

money for contingency operations. The FY 2017<br />

<strong>Army</strong> budget is expected to be only 2.2 percent larger.<br />

The agreement includes $129 billion for military personnel,<br />

a $1.2 billion increase over FY 2015. Operations and<br />

maintenance spending increase by $5.8 billion, to $167.5 billion<br />

for FY 2016. There are large increases for procurement<br />

and research programs. Procurement spending is $110 billion<br />

for 2016, a $17 billion increase over the 2015 budget. Funding<br />

of research and development programs is $69.8 billion for<br />

FY 2016, a $6.1 billion increase.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong>’s share is $53.5 billion for active, National<br />

Guard and <strong>Army</strong> Reserve personnel; and $41.7 billion in the<br />

base budget for operations and maintenance. For procurement,<br />

the compromise gives the <strong>Army</strong> $5.9 billion for aircraft,<br />

$1.9 billion for tracked vehicles, $1.6 billion for missiles,<br />

$1.2 billion for ammunition, and $5.7 billion for other<br />

procurement. The <strong>Army</strong> also receives $7.5 billion for research,<br />

development, test and evaluation; and $1.5 billion for<br />

military construction and family housing.<br />

6 ARMY ■ February 2016

News Call<br />

Animal-Assisted Therapy Can Help With PTSD<br />

Animal-assisted therapy is offering<br />

an alternative or supplement to the<br />

cognitive processing and prolonged exposure<br />

therapies currently in use to<br />

help military veterans who suffer from<br />

nightmares, depression and other effects<br />

of post-traumatic stress disorder.<br />

The trauma-focused talk therapies have<br />

been known to help, but as a study recently<br />

published in the Journal of the<br />

American Medical Association notes, “nonresponse<br />

rates have been high.” Some<br />

PTSD patients, for example, find the<br />

therapy so upsetting that they drop out.<br />

Dogs have served soldiers for decades<br />

and have proven helpful in easing PTSD.<br />

Horses have helped, too. Brooke <strong>Army</strong><br />

Medical Center in San Antonio offers<br />

equine-assisted therapy. So do VA facilities<br />

in Bedford, Mass., and Albany,<br />

N.Y. In 2010, retired Lt. Col. Bridget<br />

Kroger founded her own organization.<br />

After equine therapy helped her recover<br />

from PTSD, the 24-year <strong>Army</strong> veteran,<br />

who served two tours in Iraq, established<br />

the Wounded Warrior Equestrian<br />

Program to help riding facilities<br />

and horse-rescue farms provide services<br />

to service members and veterans around<br />

the country.<br />

Patrick Bradley, a Vietnam veteran<br />

who suffered from PTSD, recognized<br />

the symptoms when his son Skyler left<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> after more than a decade in<br />

uniform and multiple tours in Iraq and<br />

Afghanistan. Bradley, director of the<br />

raptor program at a Florida nature park,<br />

persuaded his son to visit him at work.<br />

Skyler Bradley found peace among the<br />

wounded birds of prey and soon was<br />

spending a lot of time at the park. He<br />

also began training the birds.<br />

Together, the Bradleys established the<br />

Avian Veteran Alliance and have teamed<br />

with the local VA center where Skyler<br />

was once a patient. Veterans visit the<br />

park twice a week to work with wounded<br />

raptors, and Patrick Bradley takes the<br />

birds to the VA center each month.<br />

Matthew Simmons, who served in<br />

Operations Desert Storm and Desert<br />

Shield, directs operations at the Serenity<br />

Park Parrot Sanctuary on the West Los<br />

Angeles VA campus. His wife, clinical<br />

psychologist Lorin Lindner, founded the<br />

park in 2005. It adopts sick, wounded<br />

and abandoned parrots and lets wounded<br />

warriors care for and establish relationships<br />

with them.<br />

Simmons and Lindner also established<br />

the Lockwood Animal Rescue Center<br />

north of Los Angeles in 2011. It shelters<br />

and rehabilitates wolves and wolf dogs<br />

from around the U.S. and pairs them<br />

with veterans who suffer from PTSD.<br />

Research has shown that touching an<br />

animal can lower blood pressure, relieve<br />

stress and reduce anxiety. As veterans<br />

work with and care for the animals, they<br />

build confidence and self-esteem as well<br />

as accept responsibility.<br />

—Toni Eugene<br />

Staff Sgt. Cedric Richardson rides Gary the horse at the Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston<br />

Equestrian Center. Riding is part of the Soldier Adaptive Reconditioning Program at Brooke <strong>Army</strong><br />

Medical Center.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Warns: Be Vigilant Against <strong>On</strong>line Scams<br />

This Valentine’s Day, you might be<br />

someone’s sweetheart and not even know<br />

it. That’s because imposter accounts online<br />

have proliferated. No one is immune;<br />

as Gen. John F. Campbell, commander<br />

of Resolute Support and U.S. Forces-<br />

Afghanistan, posted on his official Facebook<br />

page about this time last year: “The<br />

intent of this page is to inform readers<br />

about activities here in Afghanistan. Unfortunately,<br />

there are individuals who<br />

copy the photos and comments from this<br />

page and create fake pages using my<br />

name to find romance and/or try to scam<br />

people out of money.”<br />

The post also noted that in the six<br />

months prior, more than 700 fake sites in<br />

Campbell’s name had been identified.<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Criminal Investigation<br />

Command has already warned people<br />

involved in online dating to “proceed<br />

with caution when corresponding with<br />

persons claiming to be U.S. soldiers currently<br />

serving in Afghanistan or elsewhere.”<br />

In addition, the <strong>Army</strong> recently<br />

released a tip sheet for soldiers to reduce<br />

the chances that their names and images<br />

will be appropriated by scammers.<br />

“Imposter Accounts, Romance Scams,<br />

and Unofficial Sites” suggests soldiers<br />

take the following steps to reduce their<br />

vulnerability:<br />

■ Conduct routine searches on social<br />

media platforms for your name; public<br />

affairs professionals should also search<br />

for the names of senior leaders they rep-<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Lori Newman<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 7

esent. Be sure to search using similar<br />

spellings; imposters often use these to<br />

remain undetected.<br />

■ Set up a Google alert (www.google.<br />

com/alerts) for your name and the names<br />

of leaders you represent in an official capacity.<br />

This notification service sends<br />

emails when it finds new results—including<br />

web pages and blogs—that match<br />

the given search terms.<br />

■ Ensure privacy settings are set to<br />

the highest available for professional as<br />

well as personal accounts.<br />

The tip sheet warns that it can be difficult<br />

to remove fake accounts without<br />

proof of identity theft or scam. It also offers<br />

links for reporting imposters on Facebook,<br />

Twitter and Instagram: www.<br />

facebook.com/help/17421051939,<br />

https://support.twitter.com/forms/<br />

impersonation and https://help.instagram.<br />

com/contact/636276399721841.<br />

For more information about identifying<br />

and reporting fake accounts on social<br />

media or dating sites, go to www.army.mil/<br />

media/socialmedia.<br />

New Undersecretary Utilizing<br />

His Service in <strong>Army</strong>, Congress<br />

The new undersecretary of the <strong>Army</strong><br />

said he believes his experiences as an<br />

Iraq War veteran and member of Congress<br />

will help him in the job.<br />

Patrick Murphy, a former <strong>Army</strong> captain<br />

and staff judge advocate, spent eight<br />

years in uniform. He deployed to Bosnia<br />

in 2002 and Iraq in 2003, and also served<br />

as a constitutional law professor at the<br />

U.S. Military Academy. The 42-year-old<br />

served two terms in the U.S. House representing<br />

Pennsylvania’s 8th District.<br />

Murphy was confirmed by the Senate<br />

in a voice vote on Dec. 18, a few days after<br />

appearing before the Senate Armed<br />

Services Committee alongside the nominees<br />

for Air Force and Navy undersecretaries.<br />

Murphy told the committee<br />

that if he were confirmed for the post<br />

that makes him the <strong>Army</strong>’s chief management<br />

officer, he would engage in a<br />

top-to-bottom review looking for “efficiencies<br />

within the organization so we<br />

can refocus on those warfighters who are<br />

keeping our families safe.”<br />

“I will make sure that the <strong>Army</strong> is<br />

manned, trained and equipped to accomplish<br />

what [<strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff]<br />

Gen. [Mark A.] Milley recently articu-<br />

SoldierSpeak<br />

<strong>On</strong> Helmets<br />

“Until I took this job, I had no idea what went into making this equipment, and it’s<br />

been eye-opening,” said Col. Dean M. Hoffman IV of Program Executive Office-<br />

Soldier at Fort Belvoir, Va. “Every helmet is tested probably 67 times. We take<br />

each lot that comes off the production line. We keep some, and we put them in extreme<br />

cold, hot; and constantly every year, we’re pulling them off the shelf and<br />

retesting them to make sure they’re the best.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Clearing Drop Zones<br />

“The bittersweet is my personal archenemy,” said Ben Amos, Integrated Training<br />

Area Management coordinator at Fort Devens, Mass., about the Oriental Bittersweet,<br />

an invasive species. “It’s a very rapidly growing vine that chokes out trees. It<br />

spreads like wildfire. Not only are you going to begin losing trees, which impacts<br />

the habitat, but you have dead trees falling into landing zones, dead branches<br />

falling onto people trying to train, and just basic maneuver impacts.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> A Female Soldier’s Worth<br />

“Female military members’ remarkable service in Iraq and Afghanistan showed that<br />

no military can achieve its full potential without utilizing the talents and abilities of<br />

its female citizens,” said Maj. Gen. David S. Baldwin, adjutant general of the California<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National Guard, before meeting with state legislators and Guard<br />

leaders to discuss the opening of all military occupations to women. “Rescinding all<br />

combat restrictions was more than a move toward equality, but a tactical advancement<br />

as well.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Fighting Spirit<br />

“If you can’t fight and win, then I don’t want you on the team,” said Sgt. 1st Class<br />

Matt Torres of Fort Bragg, N.C., during a leadership seminar at Fort Leavenworth,<br />

Kan. He worries some NCOs have become stagnant in their careers and are willing to<br />

“sit back and chill” while waiting for retirement.<br />

<strong>On</strong> Turkey Jerky<br />

“To see soldiers eat and like something that you have developed, and see that it<br />

improves their morale and helps them perform their mission better—I think that is<br />

the most fulfilling my job as a researcher can get,” said Dr. Tom Yang, a food<br />

technologist at the Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering<br />

Center’s Combat Feeding Directorate in Massachusetts. He helped develop<br />

turkey jerky and turkey bacon for soldiers, using inexpensive technology and creating<br />

food that “has much less salt and stays moist.”<br />

<strong>On</strong> Mama Bears<br />

“If you thought the enemy was bad in Afghanistan, wait until my mother finds out<br />

you’re sending me to Texas,” said medically retired Capt. Florent “Flo” Groberg,<br />

recalling when <strong>Army</strong> officials said they might send him to San Antonio Military<br />

Medical Center to recover from severe injuries after he thwarted a suicide bomber<br />

in Kunar Province, Afghanistan, in 2012. Groberg, who earned the Medal of Honor<br />

for his actions, wound up at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, near his<br />

family’s home in Maryland. He spent almost three years recovering.<br />

<strong>On</strong> Giving Back<br />

“If we get wings, it’s an extra bonus,” said Staff Sgt. Micheal Tkachenko of the<br />

65th Military Police Company, Fort Bragg, N.C. “But it’s more or less about just<br />

being able to participate and give back.” Tkachenko waited in line about 26 hours<br />

to donate a toy and be first to win a chance to jump with a partner-nation jumpmaster<br />

and earn foreign jump wings, in the 18th annual Randy Oler Memorial Operation<br />

Toy Drop. Since inception, the toy drop has collected more than 100,000<br />

toys for underprivileged children.<br />

8 ARMY ■ February 2016

COMMAND SERGEANTS MAJOR and SERGEANTS MAJOR CHANGES*<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. J.A. Castillo<br />

from 19th ESC,<br />

Camp Henry, Korea,<br />

to ACC, RA, Ala.<br />

Sgt. Maj. R.J.<br />

Dore from USA<br />

Adjutant General<br />

Sgt. Maj., Fort<br />

Knox, Ky., to<br />

Forces Cmd. G-1,<br />

Fort Bragg, N.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. E.C. Dostie<br />

from USARJ and I<br />

Corps (Forward),<br />

Camp Zama, Japan,<br />

to ARCENT, Shaw<br />

AFB, S.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. C.A. Fagan<br />

from 101st Airborne<br />

Div. Artillery<br />

(Air Assault), Fort<br />

Campbell, Ky., to<br />

FCoE, Fort Sill, Okla.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.A. Ferrusi<br />

from 3rd Bde., 10th<br />

Mountain Div., Fort<br />

Polk, La., to USARAK,<br />

JB Elmendorf-<br />

Richardson, Alaska.<br />

Sgt. Maj. D. Gibbs<br />

from HQ, USASOC,<br />

Fort Bragg, to<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj., USAJFKSWCS,<br />

Fort Bragg.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.B. Manis<br />

from 205th Infantry<br />

Bde., Camp Atterbury,<br />

Ind., to First<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Division East,<br />

Fort Knox.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. D.L. Pinion<br />

from 3rd Squadron,<br />

1st U.S. Cavalry Rgt.,<br />

Fort Benning, Ga., to<br />

Sgt. Maj., USAREUR<br />

G-3, Wiesbaden,<br />

Germany.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.J. Rhoades<br />

from 21st TSC,<br />

Kaiserslautern,<br />

Germany, to<br />

Sgt. Maj., ACSIM,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Command Sgt. Maj.<br />

A.T. Stoneburg<br />

from RRS to USAREC,<br />

Fort Knox.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.A. Torres<br />

from 1st MEB, Fort<br />

Polk, to 13th SC (E),<br />

Fort Hood, Texas.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.F. Watson<br />

from Fort Belvoir<br />

Community<br />

Hospital, Fort<br />

Belvoir, Va., to<br />

PRMC, Honolulu.<br />

■ ACC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Contracting Cmd.; ACSIM—<strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff Installation Management Cmd.; AFB—Air Force Base; ARCENT—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Central; Bde.—Brigade;<br />

ESC—Expeditionary Sustainment Cmd.; FCoE—Fires Center of Excellence; HQ—Headquarters; JB—Joint Base; MEB—Maneuver Enhancement Bde.; PRMC—Pacific Regional<br />

Medical Cmd.; RA—Redstone Arsenal; Rgt.—Regiment; RRS—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Recruiting and Retention School; SC (E)—Sustainment Cmd. (Expeditionary); TSC—Theater<br />

Sustainment Cmd.; USA—U.S. <strong>Army</strong>; USAJFKSWCS—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School; USARAK—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Alaska; USAREC—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Recruiting Cmd.; USAREUR—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe; USARJ—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Japan; USASOC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Special Operations Cmd.<br />

*Command sergeants major and sergeants major positions assigned to general officer commands.<br />

U.S. House of Representatives<br />

Patrick Murphy<br />

lated as his fundamental task: to win in<br />

the unforgiving crucible of ground combat,”<br />

he said. “And I’ll make sure that<br />

our troops do not have a fair fight, that<br />

they have a tactical and technical advantage<br />

against our enemies.”<br />

Murphy told the committee that when<br />

he left Congress five years ago, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

had “45 brigade combat teams on active<br />

duty. We are now down to 31.”<br />

Resources are another concern, he<br />

said, noting the tradeoff the <strong>Army</strong> is<br />

making in slowing modernization to<br />

pay for readiness.<br />

Neera Tanden, president of the Center<br />

for American Progress, said “the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> and the nation are lucky” to have<br />

Murphy confirmed. The former senior<br />

fellow “contributed greatly to our work<br />

by leading on issues that affect 21st-century<br />

fighters, and he will no doubt do<br />

the same for the <strong>Army</strong>,” Tanden said.<br />

Briefs<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Takes Over as Chair of<br />

Conference of American Armies<br />

This month, the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> becomes<br />

chairman of the Conference of American<br />

Armies, a group of 20 member armies,<br />

five observer armies and two international<br />

military organizations from Central,<br />

South and North America that have<br />

met since 1960 to exchange defense ideas<br />

and plan conferences and exercises.<br />

The chairmanship rotates every two<br />

GENERAL<br />

OFFICER<br />

*CHANGES*<br />

Maj. Gen. J.<br />

Caravalho Jr. from<br />

Dep. Surgeon Gen.<br />

and Dep. CG (Spt.),<br />

MEDCOM, Falls<br />

Church, Va., to Jt.<br />

Staff Surgeon, Jt.<br />

Staff, Washington,<br />

D.C.<br />

Brigadier Generals: R.J. Place from Asst. Surgeon<br />

Gen. for Quality and Safety (P), OSG, and Dep. CoS,<br />

Quality and Safety (P), MEDCOM, Washington, D.C.,<br />

to CG, RHC-A (P), Fort Belvoir, Va.; R.D. Tenhet<br />

from CG, RHC-A (P), Fort Belvoir, to Dep. Surgeon<br />

Gen. and Dep. CG (Spt.), MEDCOM, Falls Church.<br />

■ CoS—Chief of Staff; Jt.—Joint; MEDCOM—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Medical Cmd.; OSG—Office of the Surgeon<br />

General; (P)—Provisional; RHC-A—Regional Health<br />

Cmd.-Atlantic; Spt. —Support.<br />

*Assignments to general officer slots announced by<br />

the General Officer Management Office, Department<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong>. Some officers are listed at the<br />

grade to which they are nominated, promotable or<br />

eligible to be frocked. The reporting dates for some<br />

officers may not yet be determined.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 9

West Named <strong>Army</strong> Surgeon General<br />

Maj. Gen. Nadja West is sworn in as the <strong>Army</strong>’s<br />

44th surgeon general and commanding general<br />

of U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Command by acting<br />

Secretary of the <strong>Army</strong> Eric Fanning. As part of<br />

her new assignment, West will be promoted to<br />

lieutenant general, the first African-American<br />

woman in the <strong>Army</strong> to hold the rank. She succeeds<br />

Lt. Gen. Patricia D. Horoho, who retired.<br />

years; this is first time in 24 years that it<br />

has fallen to the U.S.<br />

“Our cooperation over the past 55<br />

years has promoted regional security and<br />

the democratic development of our<br />

member countries,” <strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff<br />

Gen. Mark A. Milley said at the closing<br />

of the group’s 2015 conference in Colombia.<br />

It “provides our armies the opportunity<br />

to increase cooperation and<br />

integration … and, most importantly,<br />

identify the topics of mutual interest in<br />

defense-related matters to develop solutions<br />

that are beneficial to us all.”<br />

DoD: Security in Afghanistan<br />

Deteriorated Last Half of ’15<br />

DoD has acknowledged in a recent<br />

report, “Enhancing Security and Stability<br />

in Afghanistan,” that “the overall security<br />

situation in Afghanistan deteriorated”<br />

in the second half of 2015, “with<br />

an increase in effective insurgent attacks<br />

and higher ANDSF [Afghan National<br />

Defense and Security Forces] and Taliban<br />

casualties.” The report, the second<br />

mandated by Congress in the National<br />

Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal<br />

Year 2015, covers the period from June<br />

1 through Nov. 30.<br />

“Fighting has been nearly continuous<br />

since February 2015,” the report says.<br />

SENIOR EXECUTIVE SERVICE<br />

ANNOUNCEMENTS<br />

R. Kazimer, Tier 2, from<br />

Dir., Corporate Info., CIO,<br />

USACE, Washington, D.C.,<br />

to Dep. to the CG, CCoE,<br />

TRADOC, Fort Gordon, Ga.<br />

Tier 1: L. Swan to Dep. Dir., Rapid Capability<br />

Delivery, JIDA, Washington, D.C.<br />

■ CIO—Chief Information Officer; CCoE—<br />

Cyber Ctr. of Excellence; JIDA—Joint Improvised-<br />

Threat Defeat Agency; TRADOC—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Training and Doctrine Cmd.; USACE—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Corps of Engineers.<br />

The ANDSF are now capable of clearing<br />

areas of insurgents, but their ability<br />

“to hold areas after initial clearing operations<br />

is uneven [and] they remain<br />

reluctant to pursue the Taliban into<br />

their traditional safe havens.”<br />

In the six-month reporting period, 12<br />

U.S. service members were killed in<br />

Afghanistan, and 40 were wounded in<br />

action. Insider attacks are still a threat,<br />

although the number continues to decline.<br />

Terrorist and insurgent groups—<br />

particularly al-Qaida—and the possible<br />

expansion of extremist groups such as<br />

the Islamic State are threats to progress<br />

as well as security.<br />

U.S. forces in Afghanistan, now<br />

numbering nearly 10,000, are expected<br />

to remain through most of 2016.<br />

Summit Links Soldier<br />

Readiness To Sleep<br />

Fatigue can lead to mistakes, and the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has begun to focus on the importance<br />

of adequate and quality sleep to<br />

soldiers’ performance.<br />

Staff Sgt. Jacob Miller, 2015 Drill<br />

Sergeant of the Year, told attendees at a<br />

sleep summit sponsored by the <strong>Army</strong><br />

Office of the Surgeon General that he<br />

recognized he had put himself and his<br />

soldiers at risk more than once due to<br />

exhaustion after serving long duty<br />

hours. Miller acknowledged that the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has accorded more time for sleep<br />

since then, but he believes more enforcement<br />

of that guidance is needed.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> sleep specialists at the summit<br />

agreed that quality sleep is imperative to<br />

good safety and that more data is needed<br />

to show the link between fatigue and<br />

poor performance. Sleep, they noted, is<br />

a critical element in the <strong>Army</strong>’s Performance<br />

Triad, which also includes activity<br />

and nutrition. The Office of the Surgeon<br />

General is currently conducting<br />

Performance Triad pilot studies.<br />

Sky’s ‘Unraveling’ Earns Praise<br />

From Literary Critics in 2015<br />

Emma Sky, a noted Middle East<br />

expert and contributor to ARMY magazine,<br />

released her memoir, The Unraveling:<br />

High Hopes and Missed Opportunities<br />

in Iraq, last year—and the literary<br />

world took notice.<br />

Her book was named one of The New<br />

York Times’ 100 Notable Books of 2015<br />

and a Times Editors’ Choice, one of the<br />

Financial Times Books of the Year, a<br />

New Statesman [U.K.] Essential Book<br />

of the Year, a Times [U.K.] Book of the<br />

Year, and one of Military Times’ Top 10<br />

Books of the Year. The book was also<br />

shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson<br />

Prize for Nonfiction for 2015.<br />

Sky is the director of Yale University’s<br />

World Fellows program and a senior fellow<br />

at Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global<br />

Affairs. Although initially opposed to<br />

the war, she volunteered to help rebuild<br />

the Iraqi government after Saddam Hussein<br />

was overthrown in 2003.<br />

She served as the Coalition Provisional<br />

Authority’s governorate coordinator<br />

of Kirkuk, Iraq, from 2003 to 2004,<br />

and as Gen. Raymond T. Odierno’s political<br />

adviser from 2007 to 2010. ✭<br />

John Martinez<br />

10 ARMY ■ February 2016

Front & Center<br />

Readiness and Capability Are Intertwined<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

There is no question about readiness<br />

being the prime responsibility of today’s<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leaders. Every public speaker,<br />

report, news column and magazine article<br />

stresses the requirement and commitment<br />

necessary to guarantee combatready<br />

forces to meet the demands of<br />

national security.<br />

I have no argument with that requirement,<br />

having lived with it in every command<br />

assignment from World War II<br />

through the Cold War. But during my<br />

years of senior command, if anyone<br />

asked for a one-word identification of<br />

my prime responsibility, I would have<br />

answered “capability.”<br />

Readiness is the responsibility of combat<br />

and combat support forces that may<br />

be committed immediately to a crisis situation—those<br />

closest to the crisis at the<br />

highest degree of readiness. Battalion and<br />

company commanders bear the brunt,<br />

but platoon and squad leaders are the<br />

front line of action. Squad leaders ensure<br />

each soldier knows his or her job and has<br />

the skills required by his or her MOS.<br />

They also create the confidence and team<br />

spirit essential for combat operations.<br />

Platoon leaders ensure that squad<br />

leaders have done their jobs, then mold<br />

the teams that must be ready to engage<br />

in the tactical tasks they are expected to<br />

perform. Company commanders supervise<br />

and validate readiness training; they<br />

also are responsible for the first rung of<br />

the capability ladder as they exercise the<br />

ability to call for and employ intelligence,<br />

fire support, logistics and coordination<br />

with other companies engaged in combat<br />

operations. They are the principal contributors<br />

to the development of the next<br />

war’s band of brothers.<br />

Battalion and brigade commanders<br />

also supervise readiness, but their primary<br />

concerns are adequate planning and then<br />

directing operations. Requiring their attention<br />

as battle action unfolds are communications<br />

that obtain fire support and<br />

resupply, maintain contact with adjacent<br />

units and higher and lower echelons, and<br />

control the activities of attached units.<br />

Division and corps commanders direct<br />

combat campaigns. They supervise readiness<br />

training during peacetime, but must<br />

presume readiness when ordered to combat.<br />

They direct combat activities, make<br />

decisions essential for sustaining operations,<br />

and ensure their staffs are sustaining<br />

the support requirements of their<br />

subordinate units. They are also responsible<br />

for recommending or requesting<br />

the additional support or resources that<br />

could expedite action or prevent failure.<br />

The highest commands in a theater of<br />

operations are almost completely concerned<br />

with capability. They must assume<br />

the readiness of the forces committed<br />

to them by the services as they plan<br />

their campaigns, guaranteeing mission<br />

success or explaining the risks involved<br />

and recommending steps to alleviate<br />

those risks.<br />

A perfect example of such a requirement<br />

was the request for an additional<br />

corps in the troop list for the Persian<br />

Gulf campaign in 1990–91. The same<br />

responsibility is borne by the Joint<br />

Chiefs of Staff and the Pentagon, where<br />

the ultimate demands of combat operations<br />

must be satisfied.<br />

When a national crisis occurs, the<br />

president is concerned almost exclusively<br />

with capability. After approving the National<br />

Military Strategy and with assurances<br />

by the Joint Chiefs of the adequacy<br />

of forces to accomplish missions appropriate<br />

to that strategy, he or she can confidently<br />

make decisions to achieve political<br />

objectives. When that system works<br />

as designed, we have military operations<br />

like Just Cause in Panama and Desert<br />

Storm in the Persian Gulf. When the<br />

system is not operable, we have had<br />

World War II and three years of losses,<br />

the Bataan Death March and the Battle<br />

of Kasserine Pass while building the<br />

forces necessary to win in Europe and<br />

the Pacific; and we have had Korea and<br />

the infamous Task Force Smith tragedy.<br />

More recently, we have had unsatisfying<br />

results in Iraq and Afghanistan, where<br />

initial successes were squandered by inadequate<br />

or overcommitments and early<br />

withdrawals.<br />

Fulfilling such a national strategy today<br />

would require an <strong>Army</strong> closer to the<br />

780,000 strength of Just Cause and the<br />

Persian Gulf than the 450,000 currently<br />

programmed for the future. It would<br />

also require restoring the Navy and Air<br />

Force of the 1990s and a continuing<br />

modernization of our nuclear deterrent.<br />

We can hope that Congress and our<br />

presidential candidates are aware of<br />

such a need and will provide a budget<br />

that does not require the services to accommodate<br />

a too small number and a<br />

great risk.<br />

■<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret., formerly<br />

served as vice chief of staff of the<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> and commander in chief of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe. He is a senior fellow<br />

of AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Rick Rzepka<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 11

Winning the War We’ve Got, Not the <strong>On</strong>e We Want<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

We need some hard thinking. We<br />

are not winning the war against<br />

al-Qaida and the Islamic State group in<br />

Iraq or Syria, or elsewhere across North<br />

and East Africa, the greater Middle<br />

East, South Asia and beyond. At best,<br />

one might argue that we are holding our<br />

own, but this is far from winning. The<br />

sooner we come to realize this, the more<br />

likely we are to identify a successful way<br />

forward. Calls for reassessment and new<br />

options with respect to the U.S. approach<br />

to this problem—especially in<br />

light of the attacks in San Bernardino,<br />

Calif., Paris and Lebanon, and the<br />

downing of the Russian civilian airliner<br />

in Sinai—have yielded little so far.<br />

The first step to any solution is to<br />

recognize the problem for what it is.<br />

The next is to recognize what has not<br />

worked. <strong>On</strong>ly then can the outlines of<br />

probable solutions emerge. Neither the<br />

“lash out, do something” approach nor<br />

the “stay the course; it’s a long war” approach<br />

will do.<br />

We are facing a global revolutionary<br />

war, with a narrative that resonates with<br />

many. Most strategists are familiar with<br />

revolutions within a state; the near-global<br />

dimension of this revolution makes it different<br />

and more complex. Our enemies<br />

are not mere criminals. They have conquered,<br />

controlled and now govern territory.<br />

As their own strategic documents<br />

describe, their intent is to eject Western<br />

influence from the region, depose apostate<br />

(in their view) governments and redraw<br />

boundaries—as they already have<br />

between Iraq and Syria, ultimately remaking<br />

the map and adjusting the international<br />

order by creating a caliphate<br />

along the lines of the former Ottoman<br />

Empire. This is part of the context<br />

within which to understand our enemies’<br />

ongoing operations and activities,<br />

whether in one of their regional theaters<br />

of operations or against those they consider<br />

the “far enemy”; that is, Europe,<br />

the U.S. and now, Russia.<br />

Other parts of this global revolution<br />

include several power struggles: one between<br />

the Arabs and Persians; another<br />

between Sunni and Shia. Further, this<br />

revolution is an intra-Sunni struggle between<br />

the very small percentage of radical<br />

and violent Sunni Muslims seeking to<br />

redefine the faith of the vast majority of<br />

other Sunni Muslims. While the broad<br />

dimensions of this power struggle are<br />

important to understand, as in any revolution,<br />

the microdynamics of how it<br />

unfolds in each particular area are perhaps<br />

more important. And again, like all<br />

revolutions, this one has not only political<br />

but also social and religious dimensions<br />

to it. The violence our enemies<br />

use is a means to further their revolutionary<br />

ends and prevail in the regional<br />

power struggles.<br />

Finally, the geographic scope of this<br />

revolution’s context makes it an international<br />

problem, not just a regional<br />

one. In fact, one aspect of this revolutionary<br />

movement is to undo the international<br />

order produced after World<br />

War II and sustained throughout the<br />

Cold War. The stability produced by<br />

this order was, in part, a result of nations<br />

primarily resorting to institutions<br />

rather than violence to resolve differences.<br />

Al-Qaida, the Islamic State and<br />

their like reject these institutions, preferring<br />

violence to establish the “order”<br />

they seek. All nations have a stake in<br />

the international system that is under<br />

attack, and those with a bigger stake<br />

have more responsibilities to preserve<br />

and adapt that system.<br />

Several conclusions derive from the<br />

type of war we’re in. First, success in this<br />

war will require a new Western-regional<br />

coalition, one that is committed to sufficiently<br />

common principles and goals and<br />

will follow a common civil-military strategy.<br />

Given the divergence of interests in<br />

the region, no “grand alliance” seems<br />

likely. But a lesser coalition, perhaps<br />

even several bilateral arrangements, may<br />

be possible. Under these conditions, no<br />

rigid universal strategy will work; a more<br />

flexible, general one may.<br />

A precisely defined “end state” may be<br />

the wrong construct to use in this war.<br />

Rather, the strategy will have to be a<br />

combination of creating local successes<br />

that build toward the future the coalition<br />

seeks. And this war cannot be won without<br />

more participation from our Arab allies.<br />

We need to study carefully, learn<br />

from and adapt to the reasons why they<br />

have been hesitant.<br />

Second, ideas and narratives are the<br />

fuel of revolutions, so the main effort of<br />

whatever counterstrategy is adopted<br />

must attack the enemies’ narrative both<br />

by coalition domestic and international<br />

actions. A counternarrative campaign is<br />

not a “spin campaign.” Rather, it stitches<br />

together domestic and international actions<br />

concerning governance, economic,<br />

social and religious policies in ways that<br />

prove our enemies’ narratives wrong, reinforce<br />

the coalition narrative, and show<br />

our enemies for what they really are.<br />

All security actions must support this<br />

main effort. Our current counternarrative<br />

campaign remains weak because<br />

our actions are disjointed and unconnected<br />

to a vision of a future different<br />

from and more compelling than that of<br />

our enemies.<br />

Third, the “tissue” that connects our<br />

enemies is as important as our enemies<br />

themselves. This connective tissue consists<br />

of the means our enemies use to recruit,<br />

radicalize, plan, prepare, execute, finance<br />

and sustain their activities. This<br />

tissue lies in the open space of normal<br />

civil and economic communications flow,<br />

a space controlled by sovereign states and<br />

their security services. We have taken<br />

some action against this “tissue” but after<br />

14 years of war, our actions clearly have<br />

not been sufficiently robust, coordinated<br />

or timely. Whatever coalition is formed<br />

will have to develop domestic and<br />

transnational norms and methods to deal<br />

with this connective tissue.<br />

Fourth, while the “solutions” to this<br />

revolution are clearly local, local governance,<br />

economic, social and religious<br />

policies are as much causative to the rise<br />

of the revolution as are the policies and<br />

actions of “external” powers. So our reassessment<br />

must address the domestic<br />

policies of coalition members that our<br />

enemies are using to their advantage.<br />

Last, the security aspects of whatever<br />

strategy the coalition adopts must include<br />

both military forces and domestic<br />

as well as transnational police forces.<br />

Our enemies operate in the space be-<br />

12 ARMY ■ February 2016

tween crime and war, and between<br />

peace and war. The coalition must close<br />

these spaces.<br />

We have allowed the revolution to<br />

spread. Like the cancer it is, the ground<br />

that this revolutionary enemy controls<br />

and the networks they have established<br />

must be reduced; how and when are the<br />

only questions. Our current efforts to reduce<br />

this threat have been insufficient. In<br />

fact, in the face of our efforts, both enemy-held<br />

territory and their networks<br />

have expanded.<br />

We are fighting a war of attrition, acting<br />

as if time is on our side. It is not.<br />

The main effort—the counterideology<br />

campaign and its governance, economic,<br />

social and religious components—will<br />

not succeed in the current security environment.<br />

So while it is a supporting effort,<br />

successful military and police security<br />

operations are essential. Here, the<br />

coalition faces one of its many hard<br />

choices: Reduce our enemies’ control<br />

and influence—in at least some of the<br />

areas in which our enemies have<br />

grown—using coalition air, ground and<br />

special operations forces in conjunction<br />

with local forces; or pace reduction<br />

upon local security force capacity. The<br />

former option will accelerate the pace of<br />

our current operations but incur one<br />

kind of risk. The latter drags out an already<br />

too-long war, which incurs other<br />

kinds of risks.<br />

This global revolution has been clear<br />

to some for years. Also clear is that the<br />

U.S. strategic approaches used since the<br />

Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks have not<br />

been sufficiently successful. Our enemies<br />

have occasionally been disrupted, parts<br />

have been dismantled; but they have not<br />

been defeated and certainly are not destroyed.<br />

In fact, they have morphed and expanded—despite<br />

14 years of war and billions<br />

of dollars spent, hundreds of “highvalue<br />

targets” and thousands of others<br />

killed, thousands of our own casualties,<br />

tens of thousands civilians dead or<br />

wounded, and hundreds of thousands of<br />

refugees spread throughout the world.<br />

Simply put: While we have had some<br />

successes, neither the expansive, nearunilateral<br />

strategy of the former Bush<br />

administration nor the minimalist, gradualist,<br />

surrogate approach of the Obama<br />

administration has worked. <strong>On</strong>e might<br />

even say that both strategies have used<br />

approaches that have strengthened the<br />

enemies’ narrative and ideology rather<br />

than diminished it. The same can be said<br />

of some of the domestic policies adopted<br />

by nations in as well as out of the region.<br />

Both administrations have treated<br />

coalition members as “contributing<br />

nations,” where contributions are sometimes<br />

combat, advisory or support troops;<br />

and other times funds, equipment, or<br />

other military or nonmilitary capabilities.<br />

This approach can create the illusion of a<br />

multinational effort, but it does not reflect<br />

a serious attempt to align nations<br />

around similar interests and common<br />

goals. Nor does it reflect an attempt to<br />

have coalition partners, together, ascribe<br />

to common principles and develop common<br />

goals and a common strategic approach<br />

to attaining those goals. A more<br />

traditional approach to coalitions would<br />

add legitimacy to the international actions<br />

that are required in waging and<br />

fighting the war against our global revolutionary<br />

enemies.<br />

With rare exception, neither administration<br />

has been able to develop and execute<br />

a set of coherent civil-military strategies,<br />

policies and campaigns. Whether<br />

viewed domestically or internationally, if<br />

the approach so far were a musical score,<br />

it would be described more as cacophony<br />

than harmony. Going forward, we need<br />

not only a better coalition and strategy,<br />

but also better collaborative bodies and<br />

processes to make decisions, take coordinated<br />

action, and adapt faster than our<br />

enemies. We have been, consistently, too<br />

slow.<br />

Where do we go from here? Most important<br />

is to rethink what we’ve been doing.<br />

Intellectual change must precede<br />

any changes in approach. Too much of<br />

our post-9/11 collective action has been<br />

taken in the haste to “do something” or<br />

to demonstrate strength. Too much has<br />

been reactive to the crisis of the day or<br />

has been discrete actions unconnected to<br />

a coherent campaign that, if successful,<br />

will attain strategic aims. And too much<br />

has been done sequentially, not simultaneously.<br />

Further, our reassessment must acknowledge<br />

that in the kind of war we’re<br />

in, “defeat” and “destruction” cannot be<br />

defined in strictly military terms. Bombs,<br />

raids and any other kind of kinetic actions<br />

are necessary, but they are not sufficient<br />

to defeat a revolutionary enemy.<br />

Destruction of a revolution requires<br />

more. Revolutions ignite moral indignation<br />

about one power arrangement,<br />

then maneuver to replace that arrangement<br />

with another promulgated as better.<br />

Bombs and raids do not take the<br />

wind out of the sail of moral indignation.<br />

As long as we act as if defeat or<br />

destruction is a military task, success<br />

will continue to elude us. We need a coherent<br />

set of civil and military strategies,<br />

policies and campaigns, in service<br />

to a broader goal.<br />

Any reassessment worthy of the name,<br />

therefore, must start by answering this<br />

question: What kind of durable political<br />

outcome will actually produce a better<br />

peace? So far, we have heard little in answer<br />

to this question. Members of whatever<br />

coalition that forms must agree at<br />

least to the principles that will guide<br />

them to a satisfactory answer.<br />

The answer to this question is fundamental<br />

because in war, strategies, policies<br />

and campaigns, whether military or nonmilitary,<br />

are merely instruments. Their<br />

value is relative; their worth can be<br />

judged only relative to their capacity to<br />

achieve the end or ends sought. What<br />

are we seeking beyond destruction of our<br />

enemies? The answer to that question<br />

must be compelling and to sustain domestic<br />

and coalition support, our actions<br />

must clearly demonstrate that we are<br />

making progress toward that end.<br />

We cannot define the war to fit our<br />

own biases. Nor can we “spin” it to fit<br />

what we want to do rather than what has<br />

to be done. The worth of whatever<br />

strategies the coalition finally chooses<br />

will be a function of how well those<br />

strategies fit the realities of the war,<br />

whether they attain the common goals at<br />

reasonable costs and time, and how easily<br />

the coalition can adapt as the war unfolds.<br />

We may not like the war we’ve<br />

got, and we may wish things were otherwise,<br />

but success in war results from<br />

dealing with reality as it is. ■<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.,<br />

Ph.D., is a former commander of Multi-<br />

National Security Transition Command-<br />

Iraq and a senior fellow of AUSA’s Institute<br />

of Land Warfare.<br />

February 2016 ■ ARMY 13

Yep, Those Were the Good Old <strong>Army</strong> Days<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

With the <strong>Army</strong> in a time of change,<br />

it is good to look back at the “good<br />

old days.” The <strong>Army</strong> between the two<br />

world wars is the best remembered “Old<br />

<strong>Army</strong>.” The Old <strong>Army</strong> has been called<br />

an athletic club, a school, a home for<br />

wayward youth and a boys’ camp, all<br />

rolled into one.<br />

The Old <strong>Army</strong> was predominately<br />

horse-drawn and very traditional.<br />

When mechanization arrived in<br />

the 1930s and the horses left the<br />

stables, it was more traumatic<br />

than just trading in brown boots<br />

for black ones and campaign<br />

hats for overseas caps. Individual<br />

squad drill was replaced by<br />

massed battalion marching formations;<br />

the M1 Garand rifle<br />

replaced the legendary Springfield<br />

with its Mauser bolt action.<br />

When it came to getting out<br />

of personal debt, there was a<br />

saying in the rural parts of the<br />

country: Don’t sell the farm. It<br />

was understood that if families<br />

could afford to hold on to their<br />

farms, they’d never starve. Also,<br />

government-subsidized life insurance<br />

for soldiers in 1917 was<br />

$10,000—about the same amount as the<br />

average farm mortgage. Thus, when a<br />

soldier was killed, the death payment to<br />

his family “bought the farm.”<br />

Another good old saying at the turn of<br />

the century was by author Hilaire Belloc:<br />

“Whatever happens, we have got the<br />

Maxim gun and they have not.” It was<br />

the Maxim gun and its follow-on derivatives<br />

that allowed English-speaking<br />

countries and France to rule most of the<br />

discovered world. But that lasted only as<br />

long as “we” had it and “they” did not.<br />

With the demise of the Old <strong>Army</strong><br />

went wrap leggings, hand-powered telephones<br />

and signal flags, washpan helmets,<br />