Current Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THE GROWTH OF KARACHI<br />

A rural town becomes a megacity on the brink<br />

U.S. CLIMATE CHANGE REFUGEES<br />

The realities of climate change hit home<br />

CHINA’S GREAT UPROOTING<br />

Moving 250M into cities<br />

Urban Migration<br />

No.01 FALL 2017<br />

1 CURRENT FALL 2017

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Monica Gallucci<br />

Creative Director<br />

Greg Salmela<br />

Features Editor<br />

Aliah El-Houni<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Cat Ashton<br />

Designer<br />

Sabrina Xiang<br />

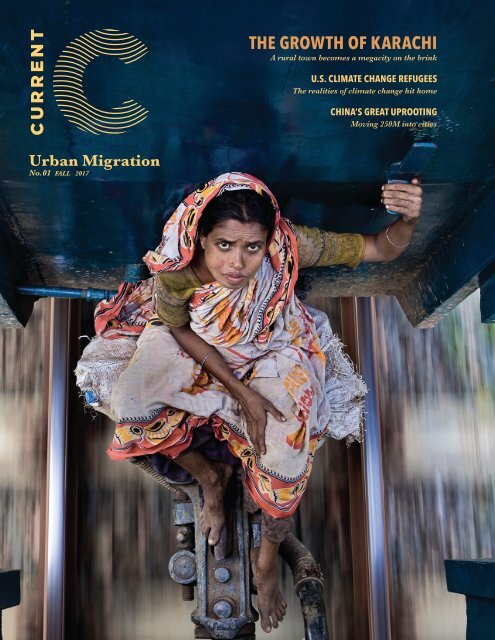

Cover Photo<br />

Steve McCurry<br />

Photographers<br />

Robin Hammond<br />

Carolyn Van Houten<br />

Justin Jin<br />

Eyevine Staff<br />

Alex Lee<br />

Stanley Greene<br />

Contributors<br />

Hiba Delawti<br />

Robin Hammond<br />

Carolyn Van Houten<br />

Azad Majumder<br />

Lily Kuo<br />

Ian Johnson<br />

Neil Arun<br />

Joseph Nevins<br />

Liz Stinson<br />

Special Thank You<br />

UBELONG<br />

Lonnie Schlein<br />

Publisher<br />

<strong>Current</strong> Publishing Ltd<br />

Website<br />

current.com<br />

Advertising / Partnerships<br />

current.com/partner<br />

Contribution Inquiries<br />

current.com/partner<br />

Stockist Inquiries<br />

current.com/stockist<br />

Follow Us<br />

Instagram // @current<br />

Twitter // @current<br />

Facebook // current<br />

6 CURRENT FALL 2017

EDITOR’S NOTE<br />

2017<br />

Tokyo<br />

38.8 M<br />

New York City<br />

23.6 M<br />

Shanghai<br />

24.1 M<br />

Seoul<br />

25.5 M<br />

Mexico City<br />

22.2 M<br />

Karachi<br />

24.3 M<br />

Delhi<br />

21.8 M<br />

Manila<br />

24.2 M<br />

Top Ten Megacities<br />

Mumbai<br />

23.6 M<br />

Jakarta<br />

31.5 M<br />

Megacity Population<br />

% Urban Population by Country<br />

< 25%<br />

25% -50%<br />

50% -75%<br />

> 75%<br />

Source: United Nations<br />

For the first time in history, more people around the globe<br />

live in cities than in rural areas, and that number is climbing<br />

at an unprecedented rate. By 2050, UNICEF estimates<br />

that 70% of the population will live in cities. The biggest<br />

shifts are happening in Africa and Asia.<br />

While the pace of urbanization varies by continent, the<br />

quest for a better life is the universal driver behind urban<br />

migration. Whether it’s climate change, politics, poverty or<br />

war that people are fleeing, they go to the cities seeking the<br />

same things; economic mobility, education and access to<br />

modern amenities. However, life in cities can be unpredictable<br />

and these things often prove elusive.<br />

Cities are struggling to accommodate their growing<br />

populations on many levels. Developing cities often lack<br />

the infrastructure, resources and economic opportunities to<br />

accommodate everyone. Developed cities are experiencing<br />

an influx of wealth that creates an inequality gap.<br />

In issue one, we will explore the specific drivers for urban<br />

migration and how they play out in people’s lives. Our<br />

feature stories traverse the world. First we find an indigenous<br />

community in Louisiana, whose way of life literally being<br />

washed away by climate change, a sign of things to come.<br />

Next we move east to China. We follow rural farmers as they<br />

experience China’s government mandated mass urbaniza-<br />

10 CURRENT FALL 2017

By 2050, 70% Of The World’s Population Will Be Urban<br />

2050<br />

Tokyo<br />

32.6 M<br />

New York City<br />

24.8 M<br />

Dhaka<br />

35.2 M<br />

Mexico City<br />

24.3 M<br />

Lagos<br />

32.6 M<br />

Karachi<br />

31.7 M<br />

Delhi<br />

36.2 M<br />

Kolkata<br />

33 M<br />

Top Ten Megacities<br />

Kinshasa<br />

35 M<br />

Mumbai<br />

42.4 M<br />

Megacity Population<br />

% Urban Population by Country<br />

< 25%<br />

25% -50%<br />

50% -75%<br />

> 75%<br />

Source: UNICEF, Business Insider<br />

tion, adjusting to life in large cities, Finally we end up in Karachi,<br />

to find a small rural city forced to become a megacity,<br />

bursting at the seams and erupting in chaos.<br />

We will examine what urban migration looks like across<br />

cultures and continents from the people experiencing it first<br />

hand. The themes of assimilation and displacement create<br />

a commonality among people who are worlds apart. The<br />

connections forged adjusting to an unfamiliar culture and<br />

way of life will be looked at closely.<br />

Kristin Lowry<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 11

CONTENTS<br />

29 37<br />

FEATURES<br />

29<br />

37<br />

THE FIRST U.S. CLIMATE REFUGEES<br />

RACE AGAINST TIME<br />

By Carolyn Van Houten<br />

A Louisiana native American tribe is forced to<br />

relocate after rising seas makes their land unlivable.<br />

CHINA’S GREAT UPROOTING<br />

By Ian Johnson,<br />

Chinese Society fundamentally changes as the country<br />

attempts the greatest urban migration in history.<br />

Moving 250M into cities.<br />

47<br />

KARACHI: UPWARD AND OUTWARD<br />

By Neil Arun<br />

One of the worlds fastest growing megacities,<br />

Karachi is cracking under the weight of its many<br />

new inhabitants.<br />

SHORT READS<br />

21<br />

25<br />

LIFE IN LAGOS — IN SEARCH OF THE<br />

AFRICAN MIDDLE CLASS<br />

Members of the middle class find a voice in<br />

a booming city defined by extreme wealth and poverty.<br />

AFRICA’S CHINESE DREAM TAKES<br />

A U-TURN<br />

For Africans who migrated to China seeking fortune,<br />

life takes an unexpected turn.<br />

12 CURRENT FALL 2017

21<br />

47<br />

57<br />

15<br />

Conversations<br />

PRINTED DOORS<br />

An interview with the creator of German Refugee<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Printed Doors.<br />

65<br />

Book Review<br />

THE LAND OF OPEN GRAVES<br />

Undocumented immigrants risk scorching temperatures,<br />

venomous creatures, and military surveillance<br />

to get into the U.S.<br />

17<br />

A Day In The Life<br />

A BANGLADESHI GARMENT WORKER<br />

The daily life of a woman who came to Bangladesh<br />

from rural India to make clothes for U.S.<br />

fashion chains.<br />

67<br />

Essay<br />

REFUGEES GET THEIR OWN FLAG<br />

Syrian refugees and artist Yara Said created a flag to<br />

represent the millions of refugees around the world.<br />

57<br />

Photo Essay<br />

THE OTHER SIDE OF MEXICAN<br />

MIGRATION<br />

A photo essay by UBELONG featuring the lives<br />

of those left behind by Mexican migrants.<br />

68<br />

DOCUMENTARIES ON NETFLIX<br />

Netflix documentaries relevant to this issue.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 13

A CONVERSATION WITH:<br />

Printed Doors<br />

BY HIBA DELAWTI<br />

Abwab <strong>Magazine</strong> helps refugees<br />

navigate a new life in Germany.<br />

Germany led the charge in opening its borders to waves<br />

of Europe-bound refugees last year. Not surprisingly, the<br />

hundreds of thousands of visitors began taking stock of their<br />

host country: new climate, food, customs, and overall lifestyle<br />

— a lot to adjust to. Ramy Al-Asheq saw many people<br />

who could use a hand navigating the new system. So, last<br />

fall, he assembled a team to help inform fellow migrants.<br />

We caught up with Ramy at his apartment in Cologne.<br />

Tell us about your personal story I’m a Syrian-Palestinian<br />

poet and journalist. I left Syria in May 2012 for Jordan. Some<br />

militias from the regime tried to kill me, because I took part<br />

in a demonstration. But, as a Palestinian-Syrian, I wasn’t<br />

allowed to stay in Jordan. I came to Germany, under an asylum<br />

grant, which protects artists and writers from dangerous<br />

and unsafe countries. I’m now editor-in-chief of Abwab, the<br />

first Arabic newspaper in Germany.<br />

What made your start Abwab? When I came to Germany,<br />

there weren’t any Arabic newspapers. I initially had the<br />

idea of making a website in two languages, Arabic and<br />

German to bridge the two communities. Then a publisher<br />

contacted me with some funding and an idea to make an<br />

Arabic print paper. Since I have a good network of writer<br />

and journalist friends, we began planning, and we launched<br />

Abwab in just a month. ‘Abwab’ means ‘doors’, so it’s like a<br />

guide to Germany.<br />

What’s your vision for the paper? We’re not in Germany<br />

because of choice. We were forced to leave our countries.<br />

As a result, we don’t know much about that culture, the<br />

life, the bureaucracy. Abwab is a newspaper by refugees,<br />

for refugees. There are articles about education, about<br />

finding food your recognize, and these pieces are written<br />

by either Germans or older Arab people who have lived<br />

here for a long time. We have sections — ‘doors’ — for<br />

international news and German news, doors for community<br />

news, reports, interviews, literature, concerts. There<br />

are two pages for feminism and women, two pages for<br />

success and happiness, and two pages for arts, literature,<br />

poetry, and caricature. So in a sense, we are a map.<br />

14 CURRENT FALL 2017

What is the biggest challenges for refugees in their<br />

first years? The language. Because without knowing German,<br />

we always have problems. And we don’t want to make<br />

mistakes. A small mistake cost me a fine, because I was on<br />

my bike and checked the time on my phone. I didn’t know<br />

it wasn’t allowed.<br />

Who are your contributors? The majority of contributors<br />

are refugees living in Germany. Our designer and layout<br />

person is in Turkey. The newsroom is in Paris; they are<br />

friends of mine. Because of my network, the majority of<br />

contributors are Syrian. But there’s Iraqi writers and journalists,<br />

(as well as) Tunisian, Libyan, Egyptian, and Palestinian.<br />

And some German.<br />

How long do you think you’ll stay in Germany? What<br />

do you miss from back home? For me, home is not a<br />

geographical area. It’s about the people you know, and<br />

the memories. I have both friends and memories in Syria,<br />

but I have lost many friends and family members and<br />

colleagues. And I lost a lot of my memory also. When I<br />

think about Damascus, there is black. A black map.<br />

But that doesn’t mean that I’ll forget my country. I will do<br />

everything I can for Syrian people. But it you asked me now,<br />

if I’d go back to Syria, with the regime, today? No. I couldn’t.<br />

What is the circulation? How do you distribute? We<br />

distribute all over Germany. The Federal Office for Migration<br />

and Refugees, will help us distribute 10,000 copies in camps.<br />

We’re also circulated in the Arab and Syrian communities<br />

here in Germany. Many refugees ask us to send them copies<br />

so that they can share with their own community.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 15

A DAY IN THE LIFE:<br />

BY AZAD MAJUMDER<br />

A Bangladeshi Garment Worker<br />

An H&M Clothing factory in Bangladesh.<br />

Parul Begum was anxious as she sloshed through puddles<br />

towards the six-story factory with flaking plaster walls. It was<br />

almost 8 a.m. and she couldn’t afford to be late. Late three<br />

times, they dock a day’s pay.<br />

Inside, almost 2,000 workers, mostly women, were making<br />

shirts — stitching, ironing, packaging. On each floor, they<br />

worked in 19 lanes, more than 100 to a lane. The air was dusty<br />

with lint so they all wore masks.<br />

Welcome to the Aplus clothing factory in Dhaka, one of<br />

countless operations supplying garments for big brand names<br />

in the West. This factory makes shirts for men and women for<br />

major discount retail chains in Europe and the United States,<br />

though the owner declined to say which ones.<br />

Among the 4 million working in Bangladesh’s booming<br />

clothing sector, those at Aplus can count themselves lucky.<br />

This is considered a “top factory”, meeting government health<br />

and safety standards and compliance codes set by buyers. Its<br />

workers earn overtime, annual vacations and maternity leave.<br />

It has a medical doctor on the premises.<br />

But despite a salary of $63 a month — 66 percent above<br />

the basic industry wage, thanks to her 25 years of experience<br />

as a sewing machine operator — Parul can scarcely make ends<br />

meet. And every day is a 12-hour slog, since she needs to<br />

accumulate overtime to pay her bills. She’s 39 years old but<br />

looks older.<br />

In Lane 13, Parul was sewing sleeves for casual shirts. She<br />

needed to sew a sleeve a minute, 60 an hour. A German buyer<br />

had ordered 450,000 shirts. If they missed their deadline, the<br />

factory would have to send the shirts by air at double the cost.<br />

Supervisors patrolled the lanes to monitor progress. Quality<br />

controllers checked the output.<br />

It was hot. Fans hummed in open widow sows. Parul was<br />

looking frail. By 11 a.m. she had sewn only 140 sleeves, 40<br />

short of her quota. She was transferred to Lane 2, where everyone<br />

was frantically working on an order for 18,000 ladies shirts<br />

for delivery to the United States a week later.<br />

Big brand names like Tommy Hilfinger and the Gap outsource<br />

to Bangladesh. Clothing accounts for 80 percent of the<br />

country’s exports and have risen five-fold in the past decade<br />

into a $21.5 billion industry.<br />

Bangladesh is now the second-largest garment exporter<br />

by value in the world after China. Few countries can compete<br />

16 CURRENT FALL 2017

with its huge supply of cheap labor and infrastructure, so foreign<br />

companies stay in the face of intensifying criticism of<br />

unsafe and exploitative working conditions.<br />

Those criticisms reached fever pitch in April when the Rana<br />

Plaza complex just outside Dhaka collapsed, killing more than<br />

1,130 people, mostly garment workers who had been told to<br />

return to work despite visible cracks in the structure.<br />

But there is little sign that foreign companies have withdrawn<br />

business from Bangladesh. Garment exports rose strongly in<br />

June and are up 13 percent over the year, government data<br />

show. It’s hard to beat Bangladesh’s labor costs, which are falling<br />

in real terms and, adjusted for the cost of living, are 27<br />

percent below nearest rival Cambodia,<br />

according to Center for American Progress/Workers<br />

Rights Consortium data.<br />

The world’s largest fashion retailers,<br />

Inditex SA, owner of the Zara chain, and<br />

H&M, are the biggest customers in Bangladesh.<br />

Europe buys about 60 percent<br />

of its apparel exports while the United<br />

States buys less than 25 percent.<br />

After the Rana Plaza disaster, 70<br />

European firms have signed a pact<br />

to better monitor and improve safety<br />

standards at the factories where they<br />

outsource, and U.S. firms have followed<br />

suit with their own accord. But<br />

clothing retailers have signed pacts before<br />

to little avail.<br />

Parul ate lunch at 1:30 p.m., sitting<br />

on the floor in the women’s canteen.<br />

The factory supplies no food and all the<br />

tables and chairs were taken. Forty-five<br />

minutes later, she was back at work.<br />

By afternoon, the garment workers were tiring. For the<br />

next six hours, Parul worked on, pausing only for some water.<br />

Tamiz Uddin Ahmed, the factory’s chief executive officer,<br />

takes pride in supplying clean drinking water. He ferries it to<br />

work in his Toyota. “We collect the water from a deep well,<br />

put it in a jar and bring to the factory every day,” he said.<br />

A doctor and two nurses are available during working<br />

hours and visits are free, a company official said. Parul has<br />

only visited the factory doctor once. She feared management<br />

might deduct money from her salary, though she does not<br />

know whether they have. She can’t read.<br />

The Aplus offices closed at 5 pm but the first batches of<br />

garment workers didn’t finish until 7 p.m. Parul was asked to<br />

stop sewing and help a fellow worker by carrying away the<br />

stitched items for the final hour.<br />

She didn’t leave work until 8:00 pm. It was dark outside.<br />

Still, she felt it was a lucky day. Her eldest daughter, Jesmin,<br />

would be waiting for her at home with her two nieces. There<br />

would a family dinner of gourd, pulse and rice.<br />

Home is a tiny room in a tin-shed shanty in the glitzy Pallabi<br />

Extension area on the northern outskirts of Dhaka, about<br />

1 kilometer and a half from the factory. The shanty has three<br />

rows, each containing six rooms, each housing four to six<br />

people. About 30 residents on each row share two toilets,<br />

one bathroom and two stoves with gas connection.<br />

Parul was 14 years old and destitute<br />

when she first came to Dhaka with<br />

her two sisters and brother in 1988. A<br />

flood had swept away her family’s small<br />

plots of land and all their possessions<br />

in Barisal district, some 250 kilometers<br />

southwest from the capital.<br />

She took a job in a garment factory<br />

for a monthly salary of Tk 150 and<br />

married a dye worker a year later. Her<br />

career coincided with the explosive<br />

growth of the ready-made garment<br />

business in Bangladesh. Her brother<br />

also is a dye worker and lives in Dhaka<br />

with his family, while her younger sister<br />

is a housemaid in Saudi Arabia.<br />

All was well until her husband had an<br />

affair. “When he left us, I was out of work<br />

because of illness,” said Parul. “My second<br />

daughter took a job in an embroidery<br />

shop and that was how we had to<br />

live — almost every day, half-fed.”<br />

Jesmin is Parul’s best hope for a better future. She has completed<br />

the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree in English at the<br />

madrasa and is promised a teaching job. If she gets it, Parul<br />

said her family will move to a better house.<br />

The only bed in the small room can hold three people at<br />

best. The others must sleep on the cement floor. The plates,<br />

glasses, cooking pots and drinking jars are placed beneath the<br />

bed to keep some space open to dine, sleep, pray and play<br />

the board game Ludo in their leisure time, if there is any.<br />

The table has an old Royal brand TV. The rest of the furniture<br />

consists of a plastic chair and two drums for keeping rice and<br />

other food items. Parul can’t afford the monthly TV satellite<br />

connection fee of Tk 300 ($3.75), or nearly two days wages.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 17

Indian women collect water from a broken<br />

pipe in a slum on the outskirts of Bangladesh.<br />

No light enters the room and the little window on the side of<br />

the aisle allows very little air to pass through. Upon entering, a<br />

visitor is greeted by an odd, goatish smell, created by so many<br />

people living in the congested space. The only ceiling fan often<br />

is stilled by frequent electricity outages.<br />

Daily life for Parul is punctuated by queuing, whenever she<br />

needs to cook food, go to the toilet or even when she brushes<br />

her teeth.<br />

Out of her salary, Parul sends Tk1,000 each month to support<br />

her mother in her village. She spends TK1,800 on rent, Tk 700<br />

on medicine and the rest goes on food. The small room in the<br />

slum costs Tk 3,100 but Parul shares costs with her two nieces.<br />

“It’s really tough to maintain the family budget,” Parul said.<br />

“Whenever someone gets sick I have to cut our food budget.”<br />

After dinner, she swallowed three tablets: a painkiller, an anti-inflammatory<br />

drug and a gastric and ulcer drug. A pharmacist<br />

had recommended she take them to sooth her aching body.<br />

She didn’t have the money to visit a doctor.<br />

Parul can barely sign her name. She doesn’t have a bank account,<br />

let alone any savings. She said she had considered working<br />

as a housemaid, the lowest ranking occupation in Bangladesh,<br />

but dropped the plan out a sense of dignity.<br />

“If I work as a housemaid, I know I will not get a good groom<br />

for my daughter,” she said.<br />

What did she think when the Rana Plaza collapsed? Did she<br />

consider quitting?<br />

“When you hear something like this it obviously creates panic,”<br />

Parul said. “But we can’t leave the job just because of this.”<br />

Photos by Stanley Greene<br />

A woman sweeps the floor<br />

in a compliant factory.<br />

18 CURRENT FALL 2017

Residents stand on their<br />

balconies at a shanty town.<br />

The 2013 Rana Plaza collapse.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 19

20 CURRENT FALL 2017

Short Read<br />

LIFE IN LAGOS<br />

In Search Of The<br />

African Middle Class<br />

Lagos, Nigeria, is Africa’s most populous metropolitan area, with an estimated 21 million<br />

inhabitants. It also boasts the biggest economy of any city in Africa, housing some<br />

of the richest people on the continent, as well as huge numbers of poor.<br />

We attempt to make understanding foreign societies easier<br />

by putting them into neat little boxes in our heads. The<br />

French are like this, the Chinese like that. It’s how we make<br />

sense of the world.<br />

The great thing about working for National Geographic is<br />

having the time to challenge preconceived ideas of a people<br />

or a place. We leave realizing that those neat little boxes<br />

don’t work; life “over there” is as complex as it is here.<br />

I went to Dolphin Estate in Lagos, Nigeria, to see a typical<br />

working-class neighborhood from where the oft-reported<br />

on African middle class was rising.<br />

Like many of my encounters in this enormous, changing<br />

city, it wasn’t what I expected.<br />

I went to Dolphin because it looked poor — the type of<br />

place where people could only go up. The buildings are ramshackle,<br />

there is rarely electricity, water must be delivered by<br />

hand, the streets are often flooded. If you were driving by, you<br />

would assume that this was a concrete slum. But that would<br />

be wrong. A closer investigation reveals more. Multiple satellite<br />

dishes hang off every building, men with briefcases and<br />

women in skirt suits come and go; the cars parked on the road<br />

outside the apartments are all modern and shiny. Come early<br />

in the morning and you would see them being cleaned. Stay<br />

a little longer and you would see that those cleaning the cars<br />

are the drivers employed to chauffeur the cars’ owners.<br />

I went to Dolphin Estate to find those who would make up<br />

the middle-class of the future and discovered that much of<br />

Dolphin Estate had already made it.<br />

But it wasn’t a simple error of judgment, it was a complex<br />

one. Along with the teachers and civil servants with shiny cars<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 21

The middle class neighborhood of Dolphin<br />

High Rise Estate, Ikoyi, Lagos, Nigeria.<br />

who make up Dolphin’s middle class, there were the mechanics<br />

and traders and tailors who don’t have cars: the working<br />

class. Then there are those who live on the estate to serve the<br />

middle class: those who deliver the water, and do odd jobs.<br />

These were mostly Nigerians<br />

from the north of the country;<br />

it’s much poorer there, so many<br />

northerners travel south in search<br />

of manual work.<br />

The more I delved, the more<br />

colorful and diverse Dolphin<br />

became. There was the young<br />

woman studying Russian at university<br />

— she proudly told me of<br />

her trip to Moscow; the young<br />

girl who wanted to be a writer,<br />

but she couldn’t read because<br />

her glasses were broken; the<br />

robe-wearing evangelist; the Manchester United fans (they’re<br />

everywhere!); The guy with the little photo studio who Photoshopped<br />

exotic backgrounds into his photos.<br />

There were teenagers whose parents had a generator and<br />

who watched “Spiderman” while the rest of the estate was<br />

without power; their apartment was so loud they couldn’t hear<br />

us knocking on the door. I met a couple who ran a non-governmental<br />

organization who proudly announced they were<br />

HIV positive before even telling me their names. I watched<br />

Chinese soap operas while children prepared for school and<br />

their father, a Muslim, made his<br />

morning prayer. I ate rice and<br />

canned fish under a spotlight after<br />

the electricity went out and<br />

plunged the apartment I was in<br />

into darkness. I peeked in on<br />

a private gym where muscular<br />

men lifted lumps of concrete,<br />

and into a makeshift fitness studio<br />

where women did aerobics.<br />

Complex communities are a<br />

challenge for storytellers. Those<br />

boxes we use to simplify and<br />

compress are helpful when describing<br />

a place, especially when you have a limited number<br />

of words and photos. But they are also a problem, especially<br />

when it comes to Africa.<br />

One of the reasons I decided to make this project about<br />

Lagos was that I wanted to make work that challenged our<br />

view of the continent. So often, people describe Africa like a<br />

22 CURRENT FALL 2017

Short Read<br />

Mr. Tajudeen Bakare is seen at his family’s home<br />

in Dolphin Estate with his daughter, Hazeezat<br />

Bakare, 11, son, Hamzat Bakare, 8, and daughter,<br />

Hammeerat Bakare, 4.<br />

Dolphin High Rise Estate,<br />

Ikoyi, Lagos, Nigeria.<br />

single country with a single<br />

11%<br />

culture. I’m often asked by<br />

well-meaning people to explain<br />

the African mentality<br />

OF NIGERIANS ARE<br />

towards such and such, or<br />

what do Africans think about<br />

MIDDLE CLASS<br />

this or that? On a continent<br />

with a population nearing a<br />

billion, and 54 countries and many, many more cultures, there<br />

is no single answer.<br />

Part of the reason I went to Lagos was to do a story about<br />

Africa’s diversity. Rather than trying to define a place with a<br />

few pictures, I wanted to create work that embraced the city’s<br />

complexity — that showed a small slice of the continent and<br />

left people with the idea that there is much more to Lagos, and<br />

to Africa, than can be captured in any article or photo essay.<br />

I went to Dolphin to find Lagos’ rising middle class. I went<br />

there falling into the usual trap of trying to define a people and<br />

a place in a narrow way.<br />

I did find the rising Lagos’ middle class in Dolphin, but I<br />

also found much more. Story and photos by Robin Hammond<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 23

24 CURRENT FALL 2017

Short Read<br />

WHEN LAMIN CEESAY, an energetic 25-year-old from Gambia,<br />

arrived in China last year, he thought his life had made a turn<br />

for the better. As the oldest of four siblings, he was responsible<br />

for caring for his family, especially after his father passed<br />

away. But jobs were few in his hometown of Tallinding Kunjang,<br />

outside of the Gambian capital of Banjul. After hearing<br />

about China’s rise, his uncle sold off his taxi business and the<br />

two of them bought a ticket and a paid local visa dealer to get<br />

them to China.<br />

“It was very developed. The tall buildings, everything was<br />

colorful. I thought, okay my life is going to change. It’s going to<br />

be better. Life is good here,” Ceesay tells Quartz, describing<br />

his first impressions of the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou.<br />

Gambia, a small country of just under 2 million people in<br />

West Africa, has been losing entire villages to migration mostly<br />

to Europe, but also to China. Chinese border restrictions have<br />

been easier than in Europe or North America and Guangzhou<br />

has become a hub for African migrants, traders, and entrepreneurs.<br />

In Gambia, youth unemployment is high,almost 40%,<br />

encouraging people like Ceesay to look east.<br />

“All I knew is that China was a world-class country and the<br />

economy is good,” he said.<br />

But Ceesay’s new life didn’t turn out quite how he imagined.<br />

The job that visa dealers promised would help him pay<br />

off his debts in three months didn’t exist. Ceesay struggled<br />

even to feed himself. When he tried to move to Hong Kong<br />

where he had heard work was better, he was escorted back to<br />

Guangzhou by police. Ceesay ended up in Thailand for three<br />

months, unsuccessfully looking for work, before coming home.<br />

Determined not to let his experience be in vain, Ceesay<br />

has turned into a campaigner against the myth of China as<br />

a promised land for Africans seeking work. “I told my uncle,<br />

I’m going back to Gambia, and I’m going to tell this story and<br />

explain what’s happening.”<br />

Ceesay went on local radio shows answering questions from<br />

callers about life and work in China. He started a Facebook<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 25

“The dream that you hoped for, the better<br />

job, better life is not there. It’s just a dream<br />

that is nowhere to be found in Asia,”<br />

being caught by the police with expired<br />

visas. Several detail struggling to<br />

get enough water and food in one of<br />

the most developed cities in China.<br />

There were also examples of people<br />

coming together. Ceesay helped orga-<br />

page, “Gambians Nightmare in China” detailing the frustrating<br />

and dangerous situations that he and other Gambians in situations as him, by asking each to contribute 5 yuan (about<br />

nize food supplies for a group of 20 Gambians, all in similar<br />

China found themselves in. Now, his story along with those $0.75) a day for food supplies. Africans from other countries<br />

of other returned Gambian migrants, is the basis of a new also showed solidarity.<br />

website called Uturn Asia, done in collaboration with migration<br />

researchers, Heidi Østbø Haugen and Manon Diederich, says Østbø Haugen.”They shared the food and water some-<br />

“The solidarity of West Africans never stops to amaze me,”<br />

from the University of Oslo and the University of Cologne. one had money to buy, and African cooks of other nationalities<br />

“The project came about because they had a strong wish gave them left-overs after their informal restaurants closed.”<br />

to warn others against coming,” says Østbø Haugen. “They It’s unclear whether the project will do much to change<br />

thought they could do so more effectively as a group than as what Østbø Haugen calls the “combination of desperation<br />

individuals, as individual accounts of failure are often written and hopefulness” that motivates many to emigrate. Several<br />

off as attempts to justify ineptness.”<br />

of those interviewed for the project went on to migrate “the<br />

On the website, Ceesay and others detail the full circle, back way” to Europe, as in by crossing the Mediterranean,<br />

or U-turn, they completed: the decision to leave home — a a dangerous sea journey that killed 4,000 migrants last year.<br />

calculus that often involved taking on heavy loans and families<br />

spending years of saving or selling off their few assets — China but decided to go to Europe instead. He died during<br />

One of the interview subjects considered moving back to<br />

optimism replaced by desperation as they ran out of money the crossing, according to Østbø Haugen.<br />

in China, and humiliation as they tried to scrabble enough Despite years of arguing with his younger brother and<br />

money together to go home.<br />

describing his own experience in China, Ceesay’s younger<br />

“The dream that you hoped for–the better job, better life– brother also left home for Europe two weeks ago, traveling<br />

to Libya where Ceesay last heard from him. By Lily Kuo,<br />

is not there. It’s just a dream that is nowhere to be found in<br />

Asia,” Ceesay says.<br />

photos by Alex Lee<br />

Ceesay’s warning is for other African communities, many<br />

of whom have had similar experiences. “What happened to<br />

them has happened to Africans of other nationalities earlier,”<br />

says Østbø Haugen, “but their desire to prevent others from<br />

ending up in the same situation is unique.”<br />

In fact, China’s African population may already be shrinking.<br />

(Researchers say the concentration of Africans in Guangzhou<br />

better known as “Chocolate City” is dispersing.) Estimates<br />

for the number of sub-Saharan Africans in Guangzhou<br />

range from 150,000 long-term residents, according to government<br />

statistics last year, to as high as 300,000 — figures<br />

complicated by the number of Africans coming in and out of<br />

the country as well as those who overstay their visas.<br />

As China’s economy slows and stricter visa requirements<br />

have been put in place, researchers say more African migrants<br />

are opting to go home. Others experience everyday<br />

racism like taxi drivers who won’t pick them up.<br />

The Gambian accounts on Uturn Asia depict a hard life for<br />

Africans in China. They describe living in cramped apartments<br />

where they have to take turns sleeping because there aren’t<br />

enough beds. Many spent their days hiding inside, afraid of<br />

26 CURRENT FALL 2017

Short Read<br />

At the end of the work day; Cletis, a<br />

trader, tries to hail a taxi to go home.<br />

African traders in Guangzhou.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 27

A Native American Tribe Struggles To Hold On To Their Culture In A<br />

Louisiana Bayou While Their Land Slips Into The Gulf Of Mexico.<br />

28 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

A SHOT RINGS OUT across what remains of Isle de Jean<br />

Charles as the sun drops behind the gnarled skeletons of<br />

what once were massive oak trees. Rifle in hand, Howard<br />

Brunet, 14, stands on the deck of his uncle’s stilted house<br />

looking down at the rabbit he shot on the far edge of the<br />

property. His sister Juliette, 13, leaps down the stairs to<br />

retrieve the body — since neither of the boys will touch it.<br />

Next comes rabbit stew. It’s a normal evening at the Brunet<br />

household. The kids are tough. The water forces them to be.<br />

“We have to be careful with the .22; we need those<br />

shells for food,” their uncle, Chris Brunet, who is raising<br />

Juliette and Howard, said as the siblings set out empty<br />

laundry-detergent containers for target practice with<br />

their cousin Reggie Parfait, 13, who lives down the road.<br />

“At one time, water was our life<br />

and now it’s almost our enemy<br />

because it is driving us out, but<br />

it still gives us life”<br />

Since 1955, the Isle de Jean Charles band of the Biloxi-<br />

Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe has lost 98 percent of its land to<br />

the encroaching Gulf waters. Of the 22,400-acre island that<br />

stood at that time, only a 320-acre strip remains. The tribe’s<br />

identity, food, and culture have slowly eroded with the land.<br />

In response, on January 21, 2016, the Department of<br />

Housing and Urban Development awarded the tribe $48<br />

million to relocate through the National Disaster Resilience<br />

Competition. But moving isn’t a simple solution.<br />

“We don’t have time,” tribal chief Albert Naquin, who<br />

spent the last 15 years advocating to relocate his people,<br />

said. “The longer we wait, the more hurricane season<br />

we have to go through. We hate to let the island go, but<br />

we have to. It is like losing a family member. We know<br />

we are going to lose it. We just don’t know when.”<br />

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaws are receiving funding,<br />

but the fight to save their culture is not over. The federal<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 29

Kenya LaMeroux wanders along<br />

Island Road, as a storm approaches.<br />

grant will help save the tribe from the eroding landscape, but<br />

addressing the effects of cultural erosion is far more difficult.<br />

“Once our island goes, the core of our tribe is lost,” said<br />

Chantel Comardelle, the deputy tribal chief ’s daughter.<br />

“We’ve lost our whole culture — that is what is on the line.”<br />

According to JR Naquin, a member of the tribe, the<br />

island once housed about 300 people, but only about 60 remain<br />

today. Much of the tribe’s heritage and traditions have<br />

faded away because the people have been scattered by land<br />

loss and rising waters. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaws<br />

haven’t been able to hold a powwow since before Hurricane<br />

Katrina hit over 10 years ago. For generations, the Biloxi-<br />

Chitimacha-Choctaws have sustained themselves off of the<br />

island’s natural resources.<br />

But today, residents say the land loss has made that untenable.<br />

“When the Great Depression hit, we didn’t know because<br />

we would just trade with each other,” says Wenceslaus<br />

Billiot, Sr., who was born, raised, and married on the island.<br />

He and his wife of 69 years, Denecia Billiot, raised their children<br />

there, but their grandchildren and great-grandchildren<br />

no longer consider it a viable place to live.<br />

Chris Brunet is the eighth generation in his family to live on<br />

the island as a member of the tribe. In one generation, “this<br />

island has gone from being self-sufficient and fertile to relying<br />

on grocery stores,” he says. “What you see now is a skeleton<br />

of the island it once was.”<br />

The land is disappearing into the Gulf because of a combination<br />

of coastal erosion, rising sea levels, lack of soil renewal,<br />

and shifting soil due to dredging for oil and gas pipeline<br />

placement. The soil that remains is nutrient-depleted because<br />

the protective marshlands that once served as the first line of<br />

defense against saltwater intrusion for the Louisiana coastline<br />

are disappearing at a rate of the area of an entire football<br />

field every hour.<br />

As the effects of climate change transform coastal communities<br />

around the world, the people of Isle de Jean Charles<br />

will be only 60 of the estimated 200 million people in coastal<br />

communities globally who could be displaced by 2050 because<br />

of climate change.<br />

Theresa Billiot, living on the island with her parents,<br />

Wenceslaus and Denecia, in order to help take care of them,<br />

commutes nearly an hour each way to her job at a grocery<br />

store in Houma, Louisiana. Her small garden between their<br />

house and the levee is one of the only remnants of the days<br />

when the tribe could live off of the land.<br />

In the distance, three oil storage tanks are visible reminders<br />

of how nearby underground pipelines have<br />

contributed to the shifting and sinking land.“It is hard for<br />

30 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Since 1955, the island has lost 98 percent<br />

of its land. Island Road, pictured, frequently<br />

washes out.<br />

everyday Americans to see and understand climate change,”<br />

Comardelle said. “They don’t see land that was once<br />

there disappear.”<br />

The island, which is thought to have been named after<br />

the father of a Frenchman who married into the tribe in the<br />

1800s, is located deep in the southern bayous of Louisiana,<br />

about 75 miles (120 kilometers) south of New Orleans and 15<br />

miles (24 kilometers) from the Gulf of Mexico.<br />

The only way into or out of Isle de Jean Charles is on<br />

Island Road. In 1953, the year the road was built, land and<br />

thick marsh surrounded the road. At that time, tribal members<br />

could traverse the land around the road to hunt and trap.<br />

But erosion is eating away at the road today. Marks of sand<br />

and debris indicate where the water covers the road during<br />

high tide. If strong southerly winds persist across the island,<br />

the road will flood even on a cloudless day.<br />

Chris Brunet says he believes that when the bayou<br />

was dredged to build up the foundation for the road, that<br />

process exposed the road and the island to more erosion.<br />

“The more avenues you create for the water, the more<br />

she’s coming,” Chris Brunet said. “It’s a powerful thing.”<br />

Every time a strong storm heads toward the island, residents<br />

have a small window of time to decide whether they<br />

will evacuate. If they don’t immediately decide to leave,<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 31

Keyondre Authement, 15, throwing rocks<br />

on the island. Attachment to the island runs<br />

deep, especially for those who shrimp and<br />

fish in the surrounding waters.<br />

Amiya Brunet, 3, on the bridge that leads<br />

to her home, which fills with up to a foot<br />

of mud during storms. Her parents, Keith<br />

Brunet and Keisha McGehee, would like to<br />

leave the island.<br />

32 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Wenceslaus Billiot, Sr., and his wife,<br />

Denecia, share a moment in their home.<br />

Wenceslaus Billiot, Jr., walks on the<br />

levee behind his parents’ stilted home.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 33

By 2050, 200 Million People Will Be<br />

Displaced Because Of Climate Change.<br />

their only choice will be to stay on the island and ride out<br />

the storm. Once the storm arrives, the road out of the<br />

island will be flooded.<br />

“It takes a lot of prayer to live down here,” Theresa<br />

Handon, Chris Brunet’s sister, said. “I think, ‘Please God,<br />

no more storms,’ but I know it’s going to come.”<br />

With every storm that hits the island comes a chance<br />

that another home will be destroyed. Louisiana contains 40<br />

percent of the nation’s wetlands, but each year an amount<br />

of land larger than the size of Manhattan is sapped from<br />

the state’s coastline. The water has now overtaken many<br />

structures that were once a part of the community. Sea<br />

level rise, shifting soils, and several hurricanes have led to<br />

the abandonment and eventual demise of what once were<br />

people’s homes.<br />

“Climate change didn’t happen overnight, so we can’t fix<br />

it overnight,” Comardelle said. “What we can do is make<br />

the best of what we’ve been given and adapt.”<br />

Many of the tribal members who remain on the island<br />

despite the rising waters are those who can’t afford any other<br />

option. Most of those who have left the island remain in the<br />

tribe but are spread throughout Louisiana.<br />

“The tribe has physically and culturally been torn apart<br />

with the scattering of members,” the resettlement proposal<br />

submitted to the Department of Housing and Urban<br />

Development’s National Disaster Resilience Competition<br />

states. “A new settlement offers an opportunity for the tribe to<br />

rebuild their homes and secure their culture on safe ground.”<br />

“We know we aren’t the only ones,” Comardelle says. “If we<br />

can do this, not only for our people, but to be a beacon of hope<br />

for other communities is important. This is not just about us.”<br />

The resettlement proposal argues that Isle de Jean Charles<br />

“is ideally positioned to develop and test resettlement adaptive<br />

methodologies,” something that is badly needed around the<br />

world. As such, the plan aims to move families to a historically<br />

contextual and culturally appropriate community.<br />

As hurricane season looms, the tribe hopes to be spared<br />

long enough to have time for relocation; however, with<br />

questions from the state about how to allocate the money,<br />

the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw culture hangs in the balance.<br />

“To stay here would have been my first choice, but common<br />

sense tells me that if I don’t take advantage now and a<br />

hurricane comes and destroys everything, then where will I<br />

go?” said the Reverend Roch Naquin, a resident who grew up<br />

on the island and was a trapper until going to seminary school.<br />

“This is not just about resettling the community on the island,”<br />

Comardelle said. “It’s reuniting the community that is left.”<br />

Having already lost so much of their land and their tribal<br />

heritage to the water, relocation is not just crucial for their<br />

personal safety but also for the longevity of their culture<br />

and traditions.<br />

“At one time, water was our life and now it’s almost our<br />

enemy because it is driving us out, but it still gives us life,”<br />

Comardelle said. “It’s a double-edged sword. It’s our life and<br />

our death.” Story and Photos by Carolyn Van Houten<br />

An aerial image reveals Island Road, which<br />

used to be surrounded by dry land but is now<br />

nearly washed out.<br />

34 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Only a handful of structures remain intact on<br />

the island, but residents fear it’s only a matter<br />

of time before those crumble, too.<br />

An abandoned boat in front of the home of<br />

Marq Naquin and Ochxia Naquin, who say<br />

they plan to stay on the island. The location<br />

of the new community has not yet been chosen,<br />

and moving is voluntary.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 35

36 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

CHINA IS PUSHING ahead with a sweeping plan to move<br />

250 million rural residents into newly constructed towns<br />

and cities over the next dozen years — a transformative<br />

event that could set off a new wave of growth or saddle<br />

the country with problems for generations to come.<br />

The government, often by fiat, is replacing small rural<br />

homes with high-rises, paving over vast swaths of farmland<br />

and drastically altering the lives of rural dwellers. So large<br />

is the scale that the number of brand-new Chinese city<br />

dwellers will approach the total urban population of the<br />

United States, in a country already bursting with megacities.<br />

This will decisively change the character of China,<br />

where the Communist Party insisted for decades that<br />

most peasants, even those working in cities, remain tied to<br />

their tiny plots of land to ensure political and economic<br />

stability. Now, the party has shifted priorities, mainly to<br />

find a new source of growth for a slowing economy that<br />

depends increasingly on a consuming class of city dwellers.<br />

The shift is occurring so quickly, and the potential costs<br />

are so high, that some fear rural China is once again the<br />

site of radical social engineering. Over the past decades, the<br />

Communist Party has flip-flopped on peasants’ rights to use<br />

land: giving small plots to farm during 1950s land reform,<br />

collecting a few years later, restoring rights at the start of the<br />

reform era and now trying to obliterate small landholders.<br />

Across China, bulldozers are leveling villages that date to<br />

long-ago dynasties. Towers now sprout skyward from dusty<br />

plains and verdant hillsides. New urban schools and hospitals<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 37

China Plans To Move 70% Of The<br />

Country Into The Cities By 2025.<br />

offer modern services, but often at the expense of the torndown<br />

temples and open-air theaters of the countryside.<br />

“It’s a new world for us in the city,” said Tian Wei, 43,<br />

a former wheat farmer in the northern province of Hebei,<br />

who now works as a night watchman at a factory. “All<br />

my life I’ve worked with my hands in the fields; do I have<br />

the educational level to keep up with the city people?”<br />

China has long been home to both some of the world’s<br />

tiniest villages and its most congested, polluted examples<br />

of urban sprawl. The ultimate goal of the government’s<br />

modernization plan is to fully integrate 70 percent of the<br />

country’s population, or roughly 900 million people, into<br />

city living by 2025. <strong>Current</strong>ly, only half that number are.<br />

The building frenzy is on display in places like Liaocheng,<br />

which grew up as an entrepôt for local wheat farmers in the<br />

North China Plain. It is now ringed by scores of 20-story<br />

towers housing now-landless farmers who have been thrust<br />

into city life. Many are giddy at their new lives – they received<br />

the apartments free, plus tens of thousands of dollars<br />

for their land — but others are uncertain about what they<br />

will do when the money runs out.<br />

Aggressive state spending is planned on new roads, hospitals,<br />

schools, community centers — which could cost upward of<br />

$600 billion a year, according to economists’ estimates. In addition,<br />

vast sums will be needed to pay for the education, health<br />

care and pensions of the ex-farmers.<br />

While the economic fortunes of many have improved in the<br />

mass move to cities, unemployment and other social woes have<br />

also followed the enormous dislocation. Some young people<br />

feel lucky to have jobs that pay survival wages of about $150<br />

a month; others wile away their days in pool halls and video-game<br />

arcades.<br />

Top-down efforts to quickly transform entire societies<br />

have often come to grief, and urbanization has already<br />

proven one of the most wrenching changes in China’s 35 years<br />

of economic transition. Land disputes account for thousands<br />

of protests each year, including dozens of cases in recent years<br />

in which people have set themselves aflame rather than relocate.<br />

The country’s new prime minister, Li Keqiang, indicated<br />

at his inaugural news conference in March that urbanization<br />

was one of his top priorities. He also cautioned, however, that<br />

it would require a series of accompanying legal changes “to<br />

overcome various problems in the course of urbanization.”<br />

Some of these problems could include chronic urban unemployment<br />

if jobs are not available, and more protests from<br />

skeptical farmers unwilling to move. Instead of creating wealth,<br />

urbanization could result in a permanent underclass in big Chinese<br />

cities and the destruction of a rural culture and religion.<br />

38 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Former farmers working on a park built<br />

over farmland in Chengdu, where the local<br />

government is razing villages and farmland<br />

on the outskirts of the city to make way for<br />

urban development.<br />

“There’s this feeling that we have to<br />

modernize, we have to urbanize and<br />

this is our national-development<br />

strategy, its almost like another<br />

Great Leap Forward.”<br />

The government has been pledging a comprehensive<br />

urbanization plan for more than four years now. It was originally<br />

to have been presented at the National People’s Congress,<br />

but various concerns delayed that, according to people<br />

close to the government. Some of them include the challenge<br />

of financing the effort, of coordinating among the various<br />

ministries and of balancing the rights of farmers, whose<br />

land has increasingly been taken forcibly for urban projects.<br />

These worries delayed a high-level conference to formalize<br />

the plan this month. The plan has now been delayed until the<br />

fall, government advisers say. Central leaders are said to be<br />

concerned that spending will lead to inflation and bad debt.<br />

Such concerns may have been behind the call in a recent<br />

government report for farmers’ property rights to be protected.<br />

Released in March, the report said China must “guarantee<br />

farmers’ property rights and interests.” Land would<br />

remain owned by the state, though, so farmers would not<br />

have ownership rights even under the new blueprint.<br />

On the ground, however, the new wave of urbanization<br />

is well under way. Almost every province has large-scale<br />

programs to move farmers into housing towers, with the<br />

farmers’ plots then given to corporations or municipalities<br />

to manage. Efforts have been made to improve the attractiveness<br />

of urban life, but the farmers caught up in the<br />

programs typically have no choice but to leave their land.<br />

The broad trend began decades ago. In the early<br />

1980s, about 80 percent of Chinese lived in the countryside<br />

versus 47 percent today, plus an additional 17<br />

percent that works in cities but is classified as rural. The<br />

idea is to speed up this process and achieve an urbanized<br />

China much faster than would occur organically.<br />

The primary motivation for the urbanization push is<br />

to change China’s economic structure, with growth based<br />

on domestic demand for products instead of relying so<br />

much on export. In theory, new urbanites mean vast new<br />

opportunities for construction companies, public transportation,<br />

utilities and appliance makers, and a break<br />

from the cycle of farmers consuming only what they<br />

produce. “If half of China’s population starts consuming,<br />

growth is inevitable,” said Li Xiangyang, vice director<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 39

Chen Hua, 50, moving to her new home in<br />

Liaocheng. Her village house was bulldozed<br />

to make way for development.<br />

A former farmer, struggling to find work,<br />

resorts to selling brooms in urban China.<br />

40 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Millions of children of migrant workers are<br />

left behind when their mothers and fathers<br />

work far from their hometowns and do not<br />

qualify for education in the cities where their<br />

parents work.<br />

Children walk to school from a housing project<br />

in Chongqing, where their families were<br />

resettled after leaving their farmland.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 41

of the Institute of World Economics and Politics, part<br />

of a government research institute. “Right now they<br />

are living in rural areas where they do not consume.”<br />

Skeptics say the government’s headlong rush to urbanize<br />

is driven by a vision of modernity that has failed<br />

elsewhere. In Brazil and Mexico, urbanization was also<br />

seen as a way to bolster economic growth. But among the<br />

“Its a different world for us in<br />

the city. All of my life I have<br />

worked with my hands. Do I have<br />

the education to keep up with<br />

city people.”<br />

results were the expansion of slums and of a stubborn<br />

unemployed underclass, according to experts.<br />

“There’s this feeling that we have to modernize, we<br />

have to urbanize and this is our national-development<br />

strategy,” said Gao Yu, China country director for the<br />

Landesa Rural Development Institute, based in Seattle.<br />

Referring to the disastrous Maoist campaign to industrialize<br />

overnight, he added, “It’s almost like another Great<br />

Leap Forward.”<br />

The costs of this top-down approach can be steep. In<br />

one survey by Landesa in 2011, 43 percent of Chinese<br />

villagers said government officials had taken or tried to<br />

take their land. That is up from 29 percent in a 2008 survey.<br />

“In a lot of cases in China, urbanization is the process<br />

of local government driving farmers into buildings while<br />

grabbing their land,” said Li Dun, a<br />

professor of public policy at Tsinghua<br />

University in Beijing.<br />

Farmers are often unwilling to<br />

leave the land because of the lack of<br />

job opportunities in the new towns.<br />

Working in a factory is sometimes an<br />

option, but most jobs are far from<br />

the newly built towns. And even if<br />

farmers do get jobs in factories, most<br />

lose them when they hit age 45 or<br />

50, since employers generally want<br />

younger, nimbler workers.<br />

“For old people like us, there’s nothing<br />

to do anymore,” said He Shifang,<br />

45, a farmer from the city of Ankang<br />

in Shaanxi Province who was relocated<br />

from her family’s farm in the mountains. “Up in the<br />

mountains we worked all the time. We had pigs and chickens.<br />

Here we just sit around and people play mah-jongg.”<br />

Some farmers who have given up their land say that when<br />

they come back home for good around this age, they have<br />

no farm to tend and thus no income. Most are still excluded<br />

from national pension plans, putting pressure on relatives<br />

to provide.<br />

The coming urbanization plan would aim to solve this by<br />

giving farmers a permanent stream of income from the land<br />

they lost. Besides a flat payout when they moved, they would<br />

receive a form of shares in their former land that would<br />

pay the equivalent of dividends over a period of decades to<br />

make sure they did not end up indigent.<br />

This has been tried experimentally, with mixed results.<br />

Outside the city of Chengdu, some farmers said they received<br />

nothing when their land was taken to build a road, leading to<br />

daily confrontations with construction crews and the police<br />

since 2014.<br />

But south of Chengdu in Shuangliu County, farmers who<br />

gave up their land for an experimental strawberry farm run<br />

by a county-owned company said they receive an annual<br />

payment equivalent to the price of 2,000 pounds of grain<br />

plus the chance to earn about $8 a day working on the<br />

new plantation.<br />

“I think it’s O.K., this deal,” said Huang Zifeng, 62, a<br />

farmer in the village of Paomageng who gave up his land<br />

to work on the plantation. “It’s more stable than farming<br />

your own land.”<br />

Financing the investment needed to start such projects<br />

is a central sticking point. Chinese economists say that the<br />

cost does not have to be completely borne by the govern-<br />

42 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

The Kan Guangfu family<br />

in front of their old home.<br />

The Kan Guangfu family in front<br />

of their new home, in southern<br />

Shaanxi Province<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 43

Ran Shunbi, 75, plays mah-jongg while holding<br />

her 3-year-old great-grandson at their<br />

relocation housing in Chongqing. She and her<br />

family were moved from their farmland and<br />

resettled nearby.<br />

“Up in the mountains we worked<br />

all the time. We had pigs and<br />

chickens. Here we just sit around<br />

and people play mah-jongg”<br />

ment, because once farmers start working in city jobs,<br />

they will start paying taxes and contributing to social<br />

welfare programs.<br />

“Urbanization can launch a process of value creation,”<br />

said Xiang Songzuo, chief economist with the Agricultural<br />

Bank of China and a deputy director of the International<br />

Monetary Institute at Renmin University. “It should start a<br />

huge flow of revenues.”<br />

Even if this is true, the government will still need significant<br />

resources to get the programs started. <strong>Current</strong>ly, local<br />

governments have limited revenues and most rely on selling<br />

land to pay for expenses — an unsustainable practice<br />

in the long run. Banks are also increasingly unwilling to<br />

lend money to big infrastructure projects, Mr. Xiang said,<br />

because many banks are now listed companies and have to<br />

satisfy investors’ requirements.<br />

“Local governments are already struggling to provide benefits<br />

to local people, so why would they want to extend this to<br />

migrant workers?” said Tom Miller, a Beijing-based author<br />

of a new book on urbanization in China, “China’s Urban<br />

Billion.” “It is essential for the central government to step in<br />

and provide funding for this.”<br />

In theory, local governments could be allowed to issue<br />

bonds, but with no reliable system of rating or selling<br />

bonds, this is unlikely in the near term. Some localities,<br />

however, are already experimenting with programs to pay<br />

for at least the infrastructure by involving private investors<br />

or large state-owned enterprises that provide seed financing.<br />

Most of the costs are borne by local governments. But<br />

they rely mostly on central government transfer payments<br />

or land sales, and without their own revenue streams they<br />

are unwilling to allow newly arrived rural residents to attend<br />

local schools or benefit from health care programs. This is<br />

reflected in the fact that China officially has a 53 percent rate<br />

of urbanization, but only about 35 percent of the population<br />

is in possession of an urban residency permit, or hukou. This<br />

is the document that permits a person to register in local<br />

schools or qualify for local medical programs.<br />

The new blueprint to be unveiled this year is supposed to<br />

break this logjam by guaranteeing some central-government<br />

44 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

A rural migrant family shops at a<br />

mall that caters to new urbanites.<br />

support for such programs, according to economists who advise<br />

the government. But the exact formulas are still unclear.<br />

Granting full urban benefits to 70 percent of the population<br />

by 2025 would mean doubling the rate of those in urban<br />

welfare programs.<br />

“Urbanization is in China’s future, but China’s rural<br />

population lags behind in enjoying the benefits of economic<br />

development,” said Li Shuguang, professor at the China<br />

University of Political Science and Law. “The rural population<br />

deserves the same benefits and rights city folks enjoy.”<br />

By Ian Johnson, Photos by Justin Jin.<br />

POPULATION OF CHINA<br />

Registered Urban<br />

44%<br />

36%<br />

Registered Rural But<br />

Living Urban<br />

Rural Population<br />

20%<br />

56%<br />

The Economist<br />

The old buildings under these high-rises in<br />

Chongqing have been marked for demolition.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 45

UPWARD AND<br />

OUTWARD<br />

46 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

Hundreds Of Thousands Have Flocked<br />

To Karachi In Search Of A Better<br />

Life, But Can The City Cope?<br />

KARACHI URBAN SPRAWL<br />

2020<br />

2013<br />

2000<br />

1991<br />

Karachi Area<br />

Landcover<br />

Source: Institute of Geographical Information Systems, City of Karachi<br />

KARACHI IS THE TEENAGE TEARAWAY of global mega-cities:<br />

it is growing up fast and doing as it pleases. Here it is growing<br />

outwards, cementing over desert and villages. Elsewhere<br />

it is building upon its buildings, growing upwards because<br />

it can no longer expand outwards, packing people into the<br />

inner city because the periphery has been exhausted.<br />

Karachi’s civic infrastructure is on the brink of collapse. It<br />

is Pakistan’s cultural and commercial capital, yet there is no<br />

city-wide system for cleaning the streets, repairing the roads,<br />

flushing the drains and providing homes with running water<br />

and steady electricity. The poor, who make up the majority<br />

of Karachi-ites, would regard the very idea of such a system<br />

as fantasy.<br />

To speak of Karachi is to speak in superlatives. It is<br />

one of the fastest growing megacities in the world and the<br />

largest city in Pakistan, which in turn is the most rapidly<br />

urbanizing nation in south Asia. To grasp what Karachi<br />

is, ask what it is not. It is not Islamabad, an orderly grid of<br />

gardens, boulevards and government buildings that supplanted<br />

Karachi as Pakistan’s capital in the 1960s. Islamabad<br />

followed the plan; Karachi ran away from it. The<br />

rationale behind Islamabad , build it and they will come , is<br />

reversed in Karachi. The people keep coming and so the<br />

city is built, stretching haphazardly along every possible axis.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 47

People cool off near a damaged water pipe.<br />

By 2025, Karachi Is Expected To<br />

Surpass 20 Million Inhabitants.<br />

Behind its expansion lies the convergence of two broader<br />

trends , natural population growth and migration to the cities.<br />

Pakistan’s overall population is growing rapidly. Those who do<br />

not already live in cities want to live in them, and Karachi is<br />

their first choice.<br />

In the last 25 years, the city’s population has more than<br />

doubled. By 2025 it is expected to have surpassed 20 million.<br />

But as more and more people make Karachi their home, it<br />

is becoming less and less habitable — a paradox shared with<br />

many developing-world megacities.<br />

When Pakistan became independent in 1947, Karachi<br />

was home to around half a million people. Today, it has 16<br />

million. How has Karachi housed them? The city , in the<br />

abstract sense of its institutions, has not. Instead, the people<br />

have housed themselves through an unregulated construction<br />

sector, and the city , in the concrete sense , is their creation.<br />

Grand schemes for the city’s expansion, poorly implemented,<br />

have been rendered obsolete. “There are so many<br />

governing agencies and bodies in Karachi,” says Sobia Kaker,<br />

a researcher at LSE Cities, a center at the London School<br />

of Economics. “They don’t follow any master plan and that<br />

creates chaos.”<br />

Like other large cities in the region, Karachi is vibrant,<br />

chaotic, polluted and overcrowded. Unlike them, it is also<br />

very violent, with a homicide rate that has been described as<br />

“Latin American” — closer to that of Bogotá than Mumbai.<br />

Much of that violence is political, a by-product of Karachi’s<br />

unique history. The city’s population are mostly migrants,<br />

refugees or their descendants, whose presence in Karachi can<br />

be traced to a series of regional conflicts. As they have settled<br />

the city the strife that brought them there has been focused on<br />

a smaller stage, in struggles for homes and influence.<br />

48 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

75% OF KARACHI’S POPULATION<br />

LIVES IN UNPLANNED SETTLEMENTS<br />

KNOWN AS KATCHI ABADI.<br />

“Karachi has developed enclaves which are predominantly<br />

ethnic or religious,” says Asiya Sadiq Polak, an architect and<br />

urban designer who has taught, researched and practiced in<br />

the city. She describes a vicious circle where each wave of<br />

newcomers congregates in neighborhoods where their community<br />

has a foothold. In this way, they shore up the constituency<br />

of community leaders, who in turn reinforce their power<br />

by using settlement as an electoral tool, awarding homes in<br />

exchange for loyalty.<br />

Karachi has thus become a network of competing fiefdoms,<br />

run by politicians and their business partners. They have undermined<br />

civic institutions to create a surrogate infrastructure that<br />

delivers services — of which housing is only one — to their<br />

clients and constituencies. It is their generators that compensate<br />

for the power cuts, their buses that workers from the outskirts,<br />

and their trucks that bring water when the taps run dry.<br />

Along with land, water is Karachi’s most precious resource.<br />

Perched between the desert and the sea, the city depends on<br />

rivers, reservoirs and wells to provide for its booming population.<br />

But many local rivers and wells have been polluted or<br />

exhausted, while reservoirs further inland have been starved<br />

by erratic rainfall.<br />

Karachi’s location, its vast population and its lack of planning<br />

mean it is also particularly vulnerable to the predicted<br />

consequences of climate change — particularly rising sea<br />

levels and frequent floods. In 2011, catastrophic flooding hit<br />

the surrounding province of Sindh, sending a tide of homeless<br />

people into the city. Pakistani scientists linked the floods<br />

to climate change and warned of worse in years to come.<br />

Karachi was originally one of several fishing villages<br />

along the delta of the Indus river. The other harbors silted up;<br />

Karachi did not. It became a port. Under British colonial rule,<br />

the port was expanded for trade and military use, attracting<br />

laborers from the rural interior. The city became a melting<br />

pot — though most of its inhabitants still spoke Sindhi, the<br />

local language.<br />

That changed with the partition of British India and the<br />

creation of Pakistan in 1947. Karachi’s substantial Hindu<br />

community fled for India, while over half-a-million Urdu-speaking<br />

Muslims left India for Karachi. The newcomers<br />

were known as mohajirs, after the Arabic word for immigrants.<br />

Having doubled the city’s population in less than five years,<br />

they also began to dominate its politics.<br />

The city swelled. Unregulated tenements sprang up on public<br />

land in the center. Those who could not find a home there<br />

— the very poor — settled on cheap, unwanted land on the<br />

periphery. Restricted by the sea to the south, this low-density<br />

sprawl stretched further and further into the desert.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 49

The residents of Benazir Colony either have<br />

to walk for a couple of kilometers to get to<br />

a bus stand or they hail an auto-rickshaw to<br />

go to a nearby main road where they can find<br />

public buses.<br />

Men try to escape the heat under a<br />

bridge during a summer heat wave.<br />

50 CURRENT FALL 2017

Feature<br />

The UN warns that millions of people in<br />

Karachi are at risk from disease because<br />

of water pollution.<br />

Pakistanis wade through a flooded<br />

road caused by heavy monsoon rainfall.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 51

Karachi’s business and financial<br />

hub stands behind China Creek.<br />

In the 1970s, the war in East Pakistan — responsible for<br />

the creation of Bangladesh — delivered another surge of<br />

migrants to Karachi. And since the 1980s, the conflicts in<br />

Afghanistan and in the adjoining border areas of Pakistan<br />

have been sending wave upon wave of Pashto-speaking<br />

migrants into the city. Each new community has announced<br />

itself with a chaotic construction spree, and by the 1980s<br />

a stunning two-thirds of the city’s population was living in<br />

unplanned settlements known as katchi abadi. The Urdu<br />

term katchi means rough, incomplete or temporary. It<br />

refers not so much to the quality of the construction as<br />

its legal status. The buildings are solid enough, and have<br />

become so common a feature of the city that the authorities<br />

eventually decided to recognize them as lawful.<br />

According to Ms Kaker, the authorities realized that<br />

rather than uprooting and rehousing people, “it might be<br />

better to regularize settlements” which they had already<br />

developed. In doing so, Karachi quietly acknowledged its<br />

failure to build for its citizens and upheld their right to build<br />

for themselves.<br />

Recently, in many parts of Karachi, the periphery has<br />

reached its limit. Remote and underdeveloped, the costs<br />

of living on the fringe have begun to outweigh any benefits.<br />

As a result, the outward expansion of the city has<br />