Current Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Feature<br />

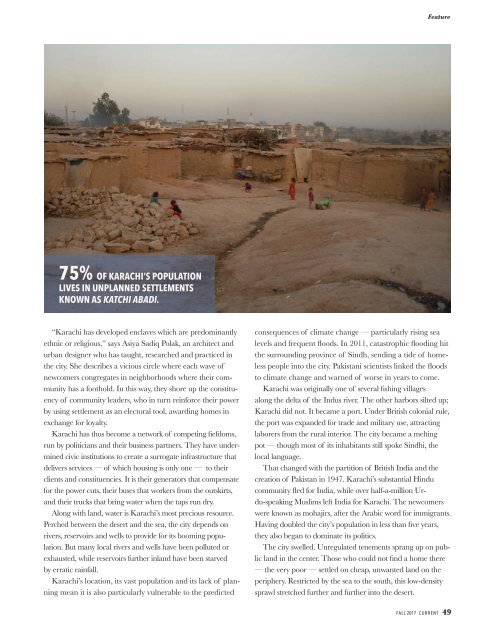

75% OF KARACHI’S POPULATION<br />

LIVES IN UNPLANNED SETTLEMENTS<br />

KNOWN AS KATCHI ABADI.<br />

“Karachi has developed enclaves which are predominantly<br />

ethnic or religious,” says Asiya Sadiq Polak, an architect and<br />

urban designer who has taught, researched and practiced in<br />

the city. She describes a vicious circle where each wave of<br />

newcomers congregates in neighborhoods where their community<br />

has a foothold. In this way, they shore up the constituency<br />

of community leaders, who in turn reinforce their power<br />

by using settlement as an electoral tool, awarding homes in<br />

exchange for loyalty.<br />

Karachi has thus become a network of competing fiefdoms,<br />

run by politicians and their business partners. They have undermined<br />

civic institutions to create a surrogate infrastructure that<br />

delivers services — of which housing is only one — to their<br />

clients and constituencies. It is their generators that compensate<br />

for the power cuts, their buses that workers from the outskirts,<br />

and their trucks that bring water when the taps run dry.<br />

Along with land, water is Karachi’s most precious resource.<br />

Perched between the desert and the sea, the city depends on<br />

rivers, reservoirs and wells to provide for its booming population.<br />

But many local rivers and wells have been polluted or<br />

exhausted, while reservoirs further inland have been starved<br />

by erratic rainfall.<br />

Karachi’s location, its vast population and its lack of planning<br />

mean it is also particularly vulnerable to the predicted<br />

consequences of climate change — particularly rising sea<br />

levels and frequent floods. In 2011, catastrophic flooding hit<br />

the surrounding province of Sindh, sending a tide of homeless<br />

people into the city. Pakistani scientists linked the floods<br />

to climate change and warned of worse in years to come.<br />

Karachi was originally one of several fishing villages<br />

along the delta of the Indus river. The other harbors silted up;<br />

Karachi did not. It became a port. Under British colonial rule,<br />

the port was expanded for trade and military use, attracting<br />

laborers from the rural interior. The city became a melting<br />

pot — though most of its inhabitants still spoke Sindhi, the<br />

local language.<br />

That changed with the partition of British India and the<br />

creation of Pakistan in 1947. Karachi’s substantial Hindu<br />

community fled for India, while over half-a-million Urdu-speaking<br />

Muslims left India for Karachi. The newcomers<br />

were known as mohajirs, after the Arabic word for immigrants.<br />

Having doubled the city’s population in less than five years,<br />

they also began to dominate its politics.<br />

The city swelled. Unregulated tenements sprang up on public<br />

land in the center. Those who could not find a home there<br />

— the very poor — settled on cheap, unwanted land on the<br />

periphery. Restricted by the sea to the south, this low-density<br />

sprawl stretched further and further into the desert.<br />

FALL 2017 CURRENT 49