Current Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

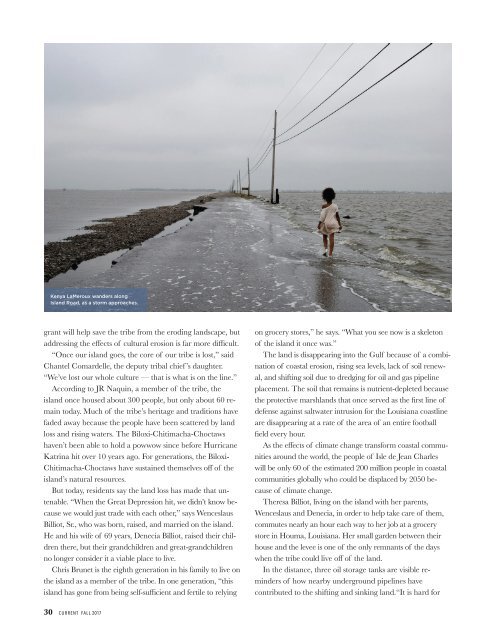

Kenya LaMeroux wanders along<br />

Island Road, as a storm approaches.<br />

grant will help save the tribe from the eroding landscape, but<br />

addressing the effects of cultural erosion is far more difficult.<br />

“Once our island goes, the core of our tribe is lost,” said<br />

Chantel Comardelle, the deputy tribal chief ’s daughter.<br />

“We’ve lost our whole culture — that is what is on the line.”<br />

According to JR Naquin, a member of the tribe, the<br />

island once housed about 300 people, but only about 60 remain<br />

today. Much of the tribe’s heritage and traditions have<br />

faded away because the people have been scattered by land<br />

loss and rising waters. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaws<br />

haven’t been able to hold a powwow since before Hurricane<br />

Katrina hit over 10 years ago. For generations, the Biloxi-<br />

Chitimacha-Choctaws have sustained themselves off of the<br />

island’s natural resources.<br />

But today, residents say the land loss has made that untenable.<br />

“When the Great Depression hit, we didn’t know because<br />

we would just trade with each other,” says Wenceslaus<br />

Billiot, Sr., who was born, raised, and married on the island.<br />

He and his wife of 69 years, Denecia Billiot, raised their children<br />

there, but their grandchildren and great-grandchildren<br />

no longer consider it a viable place to live.<br />

Chris Brunet is the eighth generation in his family to live on<br />

the island as a member of the tribe. In one generation, “this<br />

island has gone from being self-sufficient and fertile to relying<br />

on grocery stores,” he says. “What you see now is a skeleton<br />

of the island it once was.”<br />

The land is disappearing into the Gulf because of a combination<br />

of coastal erosion, rising sea levels, lack of soil renewal,<br />

and shifting soil due to dredging for oil and gas pipeline<br />

placement. The soil that remains is nutrient-depleted because<br />

the protective marshlands that once served as the first line of<br />

defense against saltwater intrusion for the Louisiana coastline<br />

are disappearing at a rate of the area of an entire football<br />

field every hour.<br />

As the effects of climate change transform coastal communities<br />

around the world, the people of Isle de Jean Charles<br />

will be only 60 of the estimated 200 million people in coastal<br />

communities globally who could be displaced by 2050 because<br />

of climate change.<br />

Theresa Billiot, living on the island with her parents,<br />

Wenceslaus and Denecia, in order to help take care of them,<br />

commutes nearly an hour each way to her job at a grocery<br />

store in Houma, Louisiana. Her small garden between their<br />

house and the levee is one of the only remnants of the days<br />

when the tribe could live off of the land.<br />

In the distance, three oil storage tanks are visible reminders<br />

of how nearby underground pipelines have<br />

contributed to the shifting and sinking land.“It is hard for<br />

30 CURRENT FALL 2017